Abstract

Objective

The aim of this review is to identify and understand the contexts that effect access to high-quality primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas.

Design

A realist review.

Data sources

MEDLINE and EMBASE electronic databases and grey literature (from inception to December 2014).

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Broad inclusion criteria were used to allow articles which were not specific, but might be relevant to the population of interest to be considered. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed for rigour and relevance and coded for concepts relating to context, mechanism or outcome.

Analysis

An overarching patient pathway was generated and used as the basis to explore contexts, causal mechanisms and outcomes.

Results

162 articles were included. Most were from the USA or the UK, cross-sectional in design and presented subgroup data by age, rurality or deprivation. From these studies, a patient pathway was generated which included 7 steps (problem identified, decision to seek help, actively seek help, obtain appointment, get to appointment, primary care interaction and outcome). Important contexts were stoicism, education status, expectations of ageing, financial resources, understanding the healthcare system, access to suitable transport, capacity within practice, the booking system and experience of healthcare. Prominent causal mechanisms were health literacy, perceived convenience, patient empowerment and responsiveness of the practice.

Conclusions

Socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas face personal, community and healthcare barriers that limit their access to primary care. Initiatives should be targeted at local contextual factors to help individuals recognise problems, feel welcome, navigate the healthcare system, book appointments easily, access appropriate transport and have sufficient time with professional staff to improve their experience of healthcare; all of which will require dedicated primary care resources.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A broad search was used to avoid missing major concepts.

The programme theory generated is transferable to other settings.

Using a realist review allowed the dynamic nature of access to healthcare to be explored.

There was a lack of evidence specifically focusing on socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas.

The context–mechanism–outcome configurations could not fully elucidate each complex interaction.

Background

Improving primary care access, defined as ‘the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible outcome’,1 has become increasingly popular because of its potential to reduce hospital admissions.2–5 In the UK, policies to improve access have included walk-in centres, extended opening, polyclinics, 48 h access and, most recently, the Prime Minister's Challenge Fund which awards grants to local organisations to improve access to primary care (total budget £100 million).6 Most of these initiatives are available to the whole population but do not target groups at high risk. A review of equality of access to healthcare in the UK found that rural individuals, older people and those in lower socioeconomic groups have poorer access to healthcare.7 When these coexist, there is likely to be intersectionality, where complex determinants of health relate, intersect and reinforce each other,8 leading to delayed diagnosis,9 poor quality of care,10 higher mortality11 and greater inequality.12 National data on this group do not exist, but by triangulating data,13 14 we estimate that there are ∼316 000 socioeconomically disadvantaged older people living in rural areas in England.

A recent systematic review assessing primary care access15 categorised barriers as patient factors (eg, sociodemographics), organisational factors (eg, appointment system), financial factors (eg, no health insurance), workforce factors (eg, technical skills) and geographical factors (eg, distance to services). As with other reviews,16 this listed the barriers, but did not encompass the dynamic, iterative and multidimensional nature of access.17 18 This reflects the traditional systematic review methodology which aims to pool data to achieve an overall result, rather than explore and explain underlying causal processes.

A realist review seeks to explore the underlying causes for observed outcomes and when these might occur by reviewing published and grey literature.19 It is designed to answers questions such as ‘how?’, ‘why?’, ‘for whom?’, ‘in what circumstances?’ and ‘to what extent?’ programmes or interventions ‘work’. Through a review of the literature, an overarching programme theory is developed which is gradually refined using data drawn from documents included as the review progresses. Within this programme theory, a realist logic of analysis is used to explore outcome patterns. In brief, mechanisms cause outcomes to occur, but the relevant mechanisms will only be ‘triggered’ under the right contexts. When applying a realist logic of analysis, a factor is only assigned the conceptual label of context if there are sufficient data to support the inference that it triggers a mechanism that causes an outcome of interest (ie, one that is relevant to and found within a programme theory). The analytic building blocks are context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs).20 These are propositions which describe what works (or happens), for whom and in what contexts and why? Contexts are conditions that trigger or modify the behaviour of mechanisms. In this realist review, we are particularly interested in identifying and understanding the contexts that act as barriers and facilitators of access to primary care. We believe that realist methods are ideal for examining access to healthcare because they can accommodate the complex and dynamic nature of access to primary care.

We aim to use a realist review to explore the contexts that influence access to primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas by seeking to answer the following questions:

What are the barriers and facilitators to accessing high-quality primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas?

What are the underlying mechanisms, why do they occur and how do they vary in different contexts?

The purpose is to understand the process of accessing primary care, rather than how to achieve a certain outcome. We did not aim to fully elucidate every underlying mechanism, but rather take a broad overview. The review is not limited to factors which are uniquely rural, since this may overlook important issues such as ease of booking an appointment. This realist review is part of a larger research programme which includes an ongoing cohort analysis, semistructured interviews and focus groups to develop an intervention that will be tested within a feasibility study.21

Methods

Programme theory development

To develop the programme theory, an initial rough theory was first produced by JAF based on prior knowledge and an initial scoping search and subsequently discussed with GW, APJ and NS. For the scoping search, we undertook a narrow search in MEDLINE and search for reports and policy documents using an internet search engine (Google) to identify key resources and understand the breadth of literature on this topic. Documents of interest were read by JAF and discussed with the research team. Key theory, such as the Aday and Andersen Framework,22 informed the initial rough theory through the use of their ‘predisposing’, ‘enabling’ and ‘need’ concepts. Based on our full search, programme theory was developed using a patient pathway that logically mapped out all the steps a patient needed to go through to access care. During the review, drawing on the data in the included studies, we then gradually and iteratively refined this patient pathway into a realist programme theory that included CMOCs.

Searching

The databases MEDLINE, MEDLINE in Process and EMBASE were searched from inception to December 2014. Search terms were initially piloted and refined to increase sensitivity. Search terms used in MEDLINE are shown in the online supplementary appendix 1. Grey literature was searched using a search engine (Google) and a targeted search of specific websites (eg, Kings Fund, Nuffield Trust and Royal College of General Practitioners). References within included documents were screened for relevance.

bmjopen-2015-010652supp.pdf (348.2KB, pdf)

Selection and appraisal of documents

All titles and abstracts were screened and articles included if they were judged to possibly contain relevant data on access to primary care in socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas. Studies did not have to include all components (ie, primary care, deprivation, older people and rural areas) because initial scoping suggested that a narrow inclusion criteria would have excluded important concepts such as ease of booking an appointment. For example, a study was eligible for inclusion if it included both rural and urban areas as long as the concepts described were relevant to socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas. Only studies published in English were included. Studies primarily focused on care homes or low-income countries were excluded. After titles and abstracts screening, we retrieved the full text of seemingly relevant articles. One author (JAF) screened all titles and abstracts. Included studies were rechecked in light of their relevance and extent to which they did actually contain data that would inform programme theory development.20 The purpose of screening and appraising was not to identify an exhaustive set of studies, but rather reach conceptual saturation in which sufficient evidence is identified to meet the aims of the review.19 After screening and rechecking, we agreed that conceptual saturation had been reached.

Data extraction and analysis

Study characteristics were extracted into a prespecified Excel spreadsheet that was piloted before use and included publication year, country, participants' details, study design and healthcare system.

Sections of relevant text were identified from included articles and coded using QRS NVivo (NVivo qualitative data analysis Software [program]. Version 10 version: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2012). Some codes were derived inductively (originating from the included studies) whereas others were deductive (originating from the initial rough theory). Codes were refined based on emerging concepts throughout the analysis period. Coded text was chosen based on the follow questions:

Is the section of text referring to context, mechanism or outcome?

What is the CMOC (partial or complete) for it?

(A) How does this (full or partial) CMOC relate to the patient pathway? (B) Are there data which support how the CMOC relates to the patient pathway? (C) In light of this CMOC and any supporting data, does the patient pathway need to be changed?

(A) Is the evidence sufficiently trustworthy and rigorous to change the CMOC? (B) Is the evidence sufficiently trustworthy and rigorous to justify changing the patient pathway?

An overarching patient pathway was developed from the data using the NVIVO coded text and the analysis aimed to find data to corroborate, refute or refine the patient pathway into a realist programme theory by gradually and iteratively building CMOCs for each step in the patient pathway. To generate the CMOCs for each step, we started with the outcome and worked backwards. Data and sections of text from the extraction phase were interpreted as relating to context, mechanism or outcome. Most sections of text described the context–outcome process without exploring the underlying mechanism, and in these situations, we sought relevant data from other included studies to identify mechanisms. We then made inferences as to what the complete CMOC might be for each step. For example, if data were interpreted as relating to context, then the next analytic task was to assess which outcome the context was related to and what the mechanism might be. Any substantive or formal theory identified during the search was used to assist in programme theory development if relevant. Included studies were re-examined throughout the analysis and programme theory refinement period using an iterative, cyclical process to seek out data to enable judgements to be made about the relevance (contributes to the research questions), rigour (the data used in programme theory development had been generated using methods that were credible and trustworthy) and importance of emerging concepts. In other words, the analysis continually asked whether there were data to warrant modifying a CMOC and/or the programme theory.

The CMOCs were discussed with the research team, which included patient representatives, and these fed into the iterative, cyclical process of searching, data extraction, analysis and programme theory development. Patient representatives were recruited from Older People's Forums in Norfolk and contributed to the design and interpretation of the research. Findings are reported in accordance with the RAMESES publication standards.23 Ethics approval was not required for this study.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

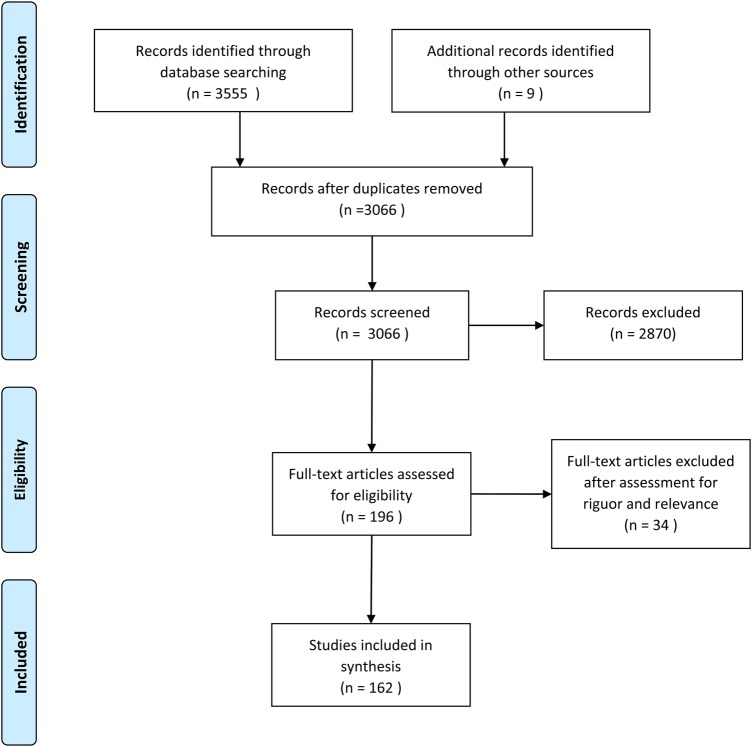

In total, 3065 titles and abstracts were screened (figure 1) leading to full-text review of 196 articles. Thirty-four articles were excluded after assessment for relevance and rigour leaving 162 to be included. Most studies were from the USA or the UK, cross-sectional in design, not disease-specific and provided subgroups of older adults, socioeconomic disadvantaged people, rurality or primary care (table 1). No studies were found that only included socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas accessing primary care.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Number of studies | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| USA | 49 |

| UK | 48 |

| Canada | 19 |

| Australia | 9 |

| New Zealand | 9 |

| Other | 28 |

| Study type | |

| Cross-sectional | 85 |

| Analysis of routine data | 24 |

| Qualitative | 22 |

| Cohort | 16 |

| Editorial or discussion paper | 3 |

| Other | 12 |

| Health problem | |

| Any health problem | 114 |

| Urgent health problems | 10 |

| Ambulatory care sensitive conditions | 8 |

| Mental health | 5 |

| COPD | 3 |

| Diabetes | 3 |

| Heart disease | 3 |

| Other | 16 |

| Age | |

| All adults | 111 |

| Older adults only | 51 |

| Socioeconomic position | |

| All adults | 150 |

| Socioeconomically disadvantaged only | 12 |

| Rurality | |

| Rural and urban | 137 |

| Rural only | 13 |

| Urban only | 12 |

| Gender | |

| Both | 157 |

| Female only | 4 |

| Male only | 1 |

| Health domain | |

| Primary care only | 69 |

| Primary and secondary | 93 |

| Subgroup analysis of relevant population | |

| Yes | 114 |

| No | 48 |

| Total | 162 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

From patient pathway to realist programme theory

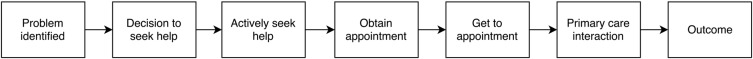

Thirty-four articles provided data that were synthesised and used to create the patient pathway (figure 2) from which the realist programme theory would be iteratively developed. The final step named ‘outcome’ refers to the result of a primary care interaction such as treatment, referral, reassurance or dissatisfaction. The first three steps (problem identified, decision to seek help and actively seek help) were described in Broadhurst24 and used by Kovandzic et al25 in a study exploring access to mental health services for hard to reach groups. The remaining steps were mainly developed from key sources.5 26–29 For example, Buetow et al27 summarised previous literature evaluating access to primary care as falling into three categories (1) organisation processes, such as appointment systems (obtaining an appointment); (2) geographical literature around physical access (getting to the appointment) and (3) social and cultural influences (cutting across both obtaining an appointment and getting to it). These data contributed to the ‘obtain appointment’ and ‘get to appointment’ steps.

Figure 2.

Patient pathway.

This patient pathway is transferable to most primary care populations and the concepts described below are particularly relevant to socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas. The patient pathway is shown as a linear pathway for simplicity, but it is clear that access to primary care is considerably more complex and dynamic.26 30 For example, a patient with an intermittent problem (such as chest pain) may transit between the first three steps (problem identified, decision to seek help and actively seek help) for days or weeks as they decide if the problem is real, warrants assessment and what the most appropriate service is.

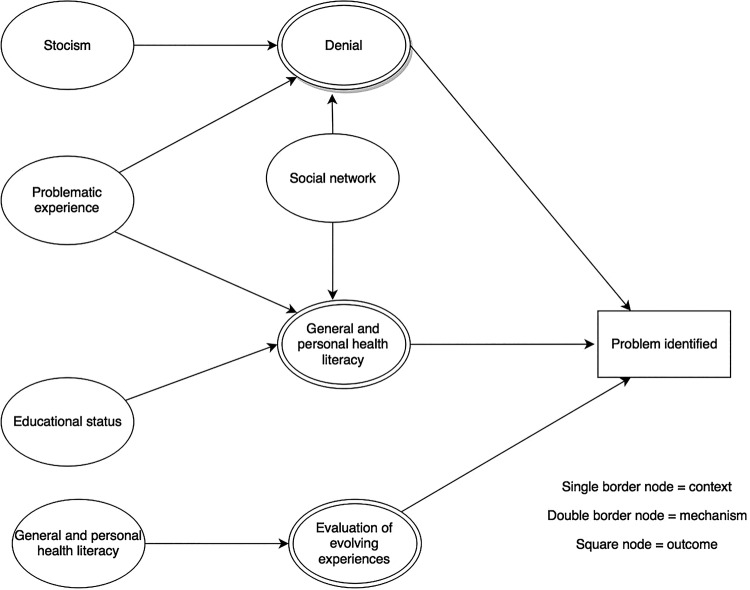

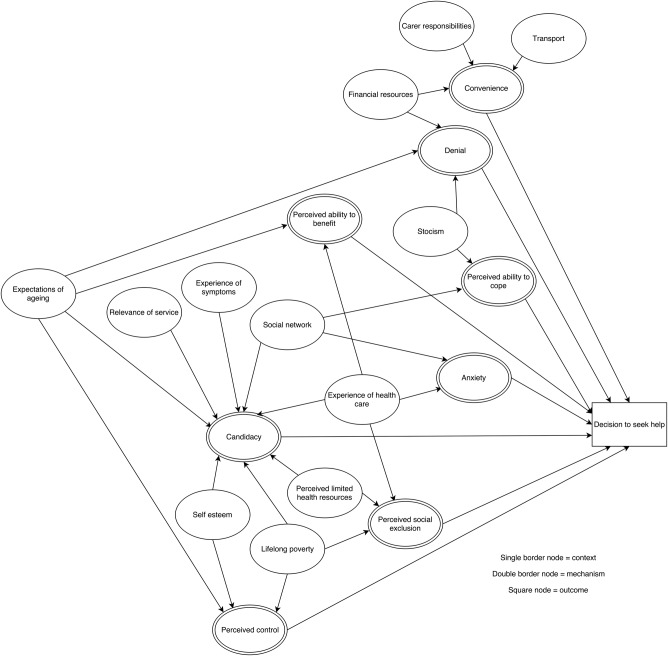

Context–mechanism–outcome configurations

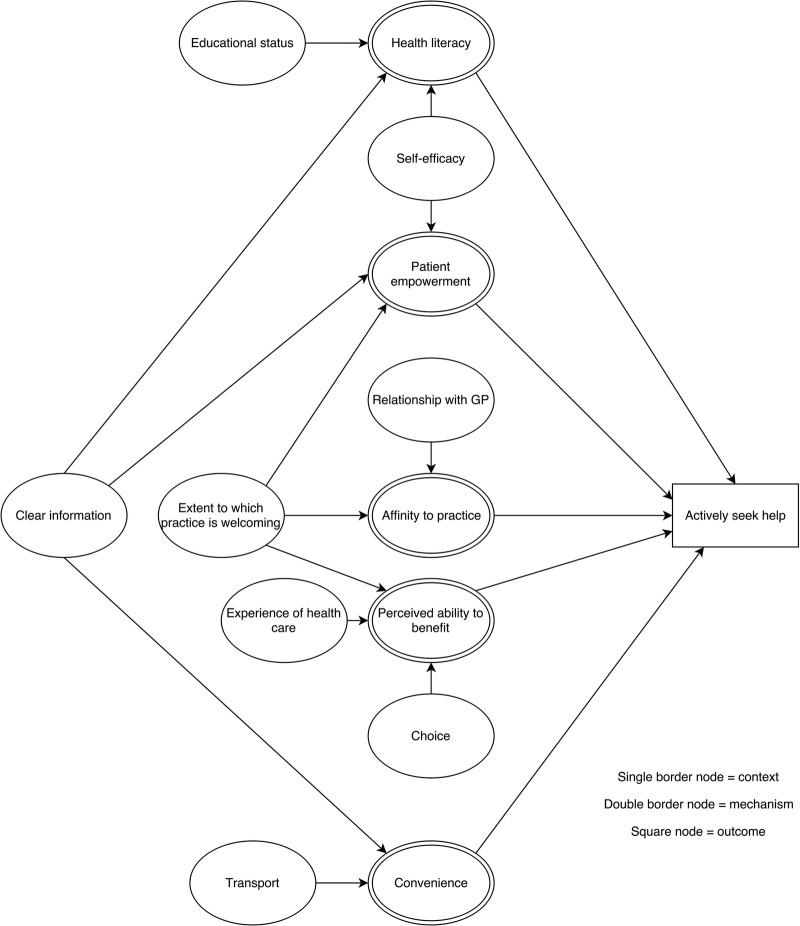

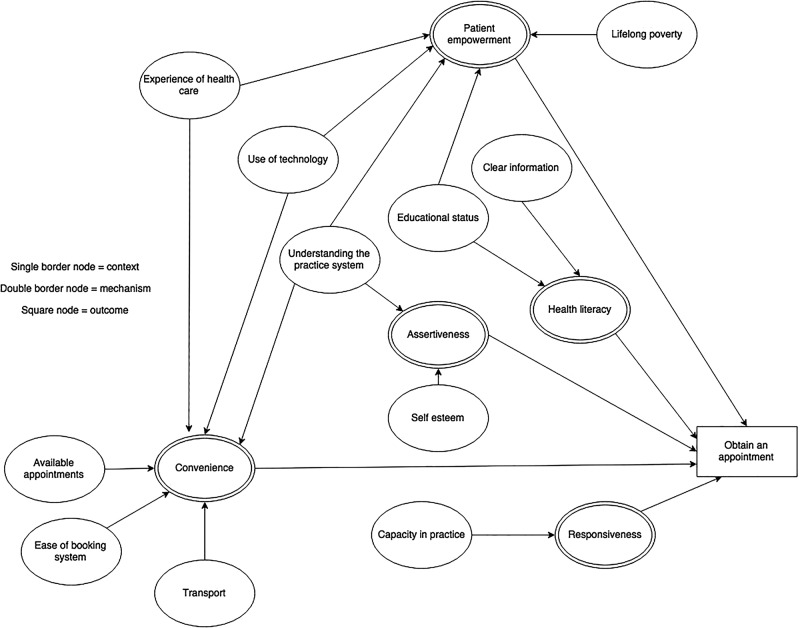

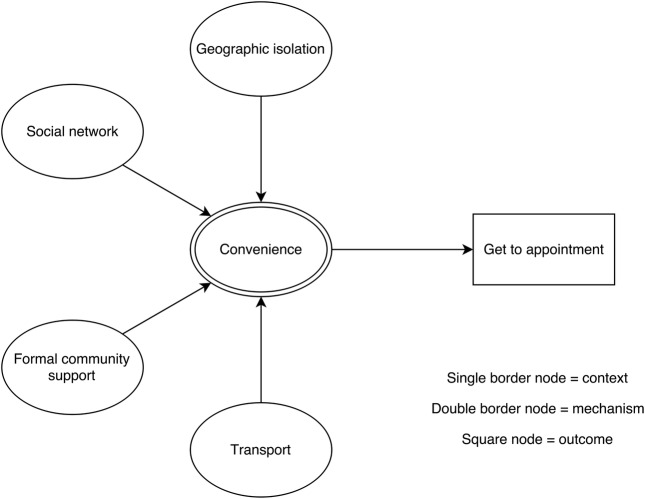

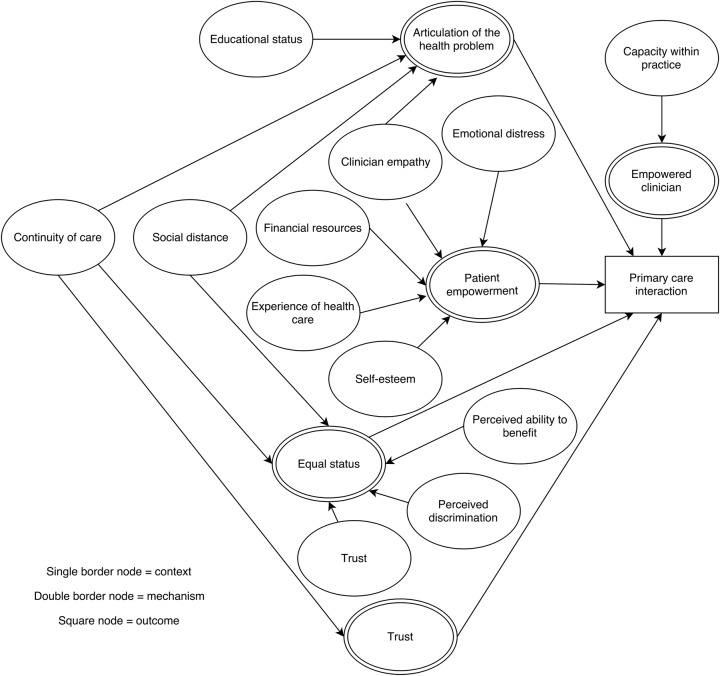

For each of the steps in the patient pathway, we developed CMOCs which can be found unconfigured in tables 2–7 and configured in figures 3–8. Detailed explanation of how data from the literature contributed to each CMOC is shown in online supplementary appendix 2.

Table 2.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for problem identified

Table 3.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for decision to seek help

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Carer responsibilities37

38 Expectations of ageing39–42 Experience of healthcare39 43–47 Experience of symptoms34 39 48 Financial resources37 49 50 51 Lifelong poverty43 52–55 Perceived limited health resources39 Relevance of services43 56 Self-esteem40 52 57 Social network58 59 Stoicism33 35 39 60 Transport61 |

Anxiety34

58 Candidacy39–41 43 44 Convenience37 49 61 Denial50 51 60 Perceived ability to benefit39 40 45 Perceived ability to cope35 39 Perceived control42 46 53 54 57 Perceived social exclusion39 47 56 55 62 |

Decision to seek help |

Table 4.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for actively seek help

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Choice32 Clear information32 56 63 Educational status64 65 Experience of healthcare35 37 Extent to which practice is welcoming33 37 66 Relationship with GP35 67 Self-efficacy68 Transport69 |

Affinity to a practice33

35

37

67 Convenience32 69 Health literacy56 64 65 Patient empowerment33 63 68 Perceived ability to benefit32 35 66 |

Actively seek help |

GP, general practitioner.

Table 5.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for obtain an appointment

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Available appointments70 Capacity within practice27 Clear information25 Ease of booking system33 Educational status65 71 Experience of health care46 Lifelong poverty72 Self-esteem56 Transport73 Understanding the practice system33 74 Use of technology75–77 |

Assertiveness33

56 Convenience27 33 70 73 75 76 78 Health literacy25 71 Patient empowerment46 65 72 74 77 Responsiveness27 |

Obtain an appointment |

Table 6.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for get to appointment

Table 7.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for primary care interaction

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity within practice81 Clinician empathy47 67 82 Continuity of care45 Educational status67 Emotional distress82 Experience of healthcare33 Financial resources83 Perceived ability to benefit71 Perceived discrimination39 Self-esteem56 71 83 84 Social distance85 86 Trust in healthcare47 85 |

Articulation of the health problem45

56

67 Empowered clinician81 Equal status39 47 71 62 85 Patient empowerment33 84 83 Trust45 |

Primary care interaction |

Figure 3.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for problem identified.

Figure 4.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for decision to seek help.

Figure 5.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for actively seek help. GP, general practitioner.

Figure 6.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for obtain appointment.

Figure 7.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for get to appointment.

Figure 8.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration for primary care interaction.

The first step in the patient pathway is identification of a problem (table 2 and figure 3). Some socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas who are experiencing symptoms may not recognise them as a problem because of poor health literacy31 32 34 linked to lower educational status31–33 (eg, unaware that unintentional weight loss could be a sign of cancer) or low social interaction or denial33 35 because of stoicism.33 Health literacy will also affect how an individual evaluates their experiences.36

After a problem has been identified, a patient will decide if they should seek help (table 3 and figure 4). For this group, important mechanisms appear to be candidacy,39–41 43 44 the effort required to attend an appointment,37 49 61 what the possible consequences will be,34 58 if the service will meet their need39 40 45 and if they can continue to manage independently without needing to seek healthcare.35 39 Contexts influencing these mechanisms include personal characteristics (such as educational status,37 expectations of ageing,39–42 stoicism33 35 39 50 60 and self-esteem);40 52 57 resources available (such as finances,37 49 51 support from friends and family,33 transport61 and carer responsibilities);38 perception of the health service (such as perceived limited resources within healthcare39) and experience of healthcare.39 44 46 47

If a patient decides that a problem warrants healthcare, the next step is to actively seek help (table 4 and figure 5). A socioeconomically disadvantaged older person in a rural area is more likely to seek help from primary care if they feel a sense of belonging to a practice33 35 37 67 which they are able to get to easily,32 56 64 65 69 believe it will be of help32 35 66 and are empowered.33 63 68 These mechanisms are influenced by experience of healthcare,35 67 educational status,64 65 personal resources such as self-efficacy68 and transport.69

Once the decision to seek primary care is made, a patient is required to obtain an appointment for most primary care services in the UK (table 5 and figure 6). Key contexts are available appointments,70 capacity within the practice,27 availability of clear information25 and ease of the booking system.33 A socioeconomically disadvantaged older person in a rural area is less likely to be able to obtain an appointment if they do not understand the system,25 71 are not assertive,33 56 appointments are not available at convenient times33 70 73 75 87–89 or the practice is not responsive to their needs.27 Other contributing contexts include available personal resources (such as transport,73 technology,75–77 educational status65 71 and experience of healthcare.46 78

After an appointment is booked, a patient needs to get there (table 6 and figure 7). Geographical isolation,79 80 local support (either social39 or community61) and access to suitable transport69 79 are all important in influencing decisions about convenience,39 61 69 79 80 and subsequent likelihood of attending the appointment for older people in this group.

The quality of the primary care interaction depends on patient and clinician factors (table 7 and figure 8). A socioeconomically disadvantaged older person in a rural area may face problems in articulating the health problem45 56 67 and feeling empowered33 83 84 to negotiate care. These were related to concepts such as continuity of care,45 educational status67 and experience of healthcare.33 The clinician needs to have empathy67 82 and capacity within practice,81 to deliver the care that is required. Capacity includes having sufficient consultation time; evidence suggests that socioeconomically disadvantaged people experience shorter consultation times90 but may have difficulty in articulating health problems, increased anxiety or feel pressured by crowded waiting rooms.85 Both patient and clinician need equal status39 47 71 85 86 which is related to patient trust in the healthcare system,47 85 consistency of care47 and social distance.56 71 83 84 86

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

Socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas face personal, community and healthcare barriers that limit their access to primary care. Key contexts identified in this review were stoicism, education status, expectations of ageing, financial resources, understanding of the system, access to suitable transport, capacity in primary care, the booking system and experience of healthcare. Key mechanisms underlying these contexts were health literacy, perceived convenience, patient empowerment and responsiveness of the practice. Realist review proved a useful approach for making sense of some of the complex and dynamic relationship of access because it allows exploration of the underlying mechanisms.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths include a broad search strategy that was not limited to studies of socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas accessing primary care. This reduced the risk of missing major concepts which were not unique but were relevant to this patient group and meant that we could take a broad overview of the topic. Furthermore, the breadth allowed sense to be made of the behaviour of some of the mechanisms under the different contexts reported in the included articles. CMOC were discussed with patients to ensure there were no obvious gaps or inconsistencies. The nature of the programme theory developed means that it can be adapted to other populations to help health service design. Our review has demonstrated that, unlike many realist reviews and literature on realist methodologies which focus on a specific intervention or programme, realist reviews can be useful to aid the development of a programme theory—in this case one that explores drivers and barriers of access to healthcare.

The main limitation was the lack of evidence specifically focusing on socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas. To overcome this, we took a broad approach, and while this meant we did not miss important concepts, some issues may not be relevant to this group. Furthermore, a broad approach meant that we had more evidence to support the programme theory. Most of this was from cross-sectional studies which generally provided information on context and outcome, while qualitative studies provided data on mechanisms. Unsurprisingly, there were no randomised controlled trials because, while they were eligible, we were not looking at a specific intervention. We did not undertake any formal assessment of the methodological rigour of each manuscript included in the review. However, we did make global judgements about the trustworthiness of data within documents or studies we used to support our inferences. Overall, we judged data to be sufficiently trustworthy to enable refinement of our programme theory.

A further limitation was that the broad approach and nature of the data meant that each CMOC could not fully elucidate each complex interaction, nor could we differentiate which contexts or mechanisms were more important than others to achieve desired outcomes. While undertaking a realist review researchers would generally become more focused to contain the large volume of data emerging.23 We purposefully kept our review broad so as to include data on the whole patient pathway because we believed that a broader programme theory would be more useful in helping us to develop and test any future interventions. Since we were able to achieve sufficient conceptual saturation for the focus of this review, we did not undertake any additional searches. No significant alterations were made to our review processes as the review progressed. Furthermore, it was not always clear what the direction of effect was within the CMOs because the limited literature, and therefore we have presented neutral CMOs.

Comparisons with existing literature

No other reviews exist in this population. Most previous work looking at access to healthcare (eg, Hoeck,91 Pong et al29) is based on the Aday and Andersen Framework,22 specifically their description of predisposing, enabling and need factors. There are similarities between our programme theory and the Aday and Andersen Framework. For example, most of our concepts could be categorised accordingly, such as educational status (predisposing), transport (enabling) and unmet need (need). However, by using realist methodology, we were able to explore underlying mechanisms and identify and understand which contexts need to be modified by interventions so as to increase the likelihood that desirable outcomes would occur. The Aday and Andersen Framework lacked this additional level of detail and understanding (and hence coherent rationale) to inform intervention design as it generally only includes contexts and outcomes. Uniquely, we have been able to develop a coherent and transferable explanation of the steps and causal processes (in the form of the realist programme theory) of access to healthcare using the specific population of socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas. This is important because we will use the findings from our review to design an intervention to address access issues faced by this population group of older people.

A comprehensive review of access to primary care looked quantitatively at whether barriers increased or decreased access for three areas: diabetes, episodic care and Pap testing.15 Our review has included similar concepts as this review, except for those relating to health insurance because we focused on relevance to the UK. However, we were more focused on understanding the underlying mechanism of, for example, the appointment system, rather than quantitatively describing each barrier. None of these studies mapped out access along a patient pathway from identifying a problem to primary care interaction. In contrast, we have developed a patient pathway which (1) allows a more targeted approach to address specific access problems and; (2) provides a coherent overview of access to primary care services.

Recommendations

Some contexts identified in the review, such as educational status and lifelong poverty, require upstream policy interventions; however, contextual factors which may be amenable to health service interventions are detailed below. Not every person will necessarily benefit from all of the below contextual changes, but our findings suggest a focus on these potential barriers.

Where there is a perception that the health system does not have sufficient resources, messages about the health services aimed at reducing unnecessary healthcare attendances and promoting self-management should be carefully phrased, so that they do not lead to vulnerable groups, who infrequently access primary care, feeling unwelcome or not entitled to health services. For example, a media campaign to encourage use of digital resources may inadvertently lead socioeconomically disadvantaged older people without IT skills feeling that health services are not relevant to them.

Where patients have a negative experience of healthcare and are at risk of poor access, organisations need to ensure that these experiences are identified and addressed to help those patients remain engaged with the service.

Where patients have carer responsibilities, opportunities for respite are needed to enable carers to attend appointments.

Where there are areas with poor public transport, community transport schemes or satellite clinics are needed to help socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas get to their appointment, especially if they do not have a support network.

Where there is a complex healthcare system, services should ensure that information is provided in plain English and in a format which is accessible to vulnerable people, especially regarding how to navigate the system.

Where practices have overstretched booking systems, practices need to be responsive to the needs of vulnerable people, such as having a priority, one-stop telephone number or protected appointments at suitable times during the day, as socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas may not be assertive and are often stoical. A balance is needed between simple, clear information and processes for patients while being flexible and able to cater for different needs.

Where there is limited capacity within practice, resources need to be prioritised to ensure that healthcare staff are able to spend the time needed to provide high-quality care to vulnerable groups which will improve their experience, keeping them engaged with primary healthcare.

Conclusion

Our realist review of access to primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas identified key contexts such as stoicism, education status, expectations of ageing, financial resources, understanding the system, access to suitable transport, capacity within practice, the booking system and experience of healthcare. Important underlying mechanisms were health literacy, perceived convenience, patient empowerment and responsiveness of the practice. Some of these contextual influences on access to care act as barriers across the patient pathway but are amenable to change and interventions should aspire to address them.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs Annie Moseley and Mrs Hillary Stringer (patient representatives) for contributing to the design and discussing the results.

Footnotes

Contributors: JAF conceived the idea. All authors contributed to the design of the review. GW provided methodological support for the review. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. JAF and GW drafted the initial manuscript and all authors contributed to drafting the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Fellowship programme grant number DRF-2014-07-083.

Disclaimer: This article/paper/report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Access to health care in America. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bankart MJ, Baker R, Rashid A et al. Characteristics of general practices associated with emergency admission rates to hospital: a cross-sectional study. Emerg Med J 2011;28:558–63. 10.1136/emj.2010.108548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soljak M, Calderon-Larranaga A, Sharma P et al. Does higher quality primary health care reduce stroke admissions? A national cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e801–7. 10.3399/bjgp11X613142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowling TE, Cecil EV, Soljak MA et al. Access to primary care and visits to emergency departments in England: a cross-sectional, population-based study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e66699 10.1371/journal.pone.0066699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young AF, Dobson AJ, Byles JE. Determinants of general practitioner use among women in Australia. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:1641–51. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00449-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS England. Prime Minister's Challenge Fund. Secondary Prime Minister's Challenge Fund, 2014. http://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/qual-clin-lead/calltoaction/pm-ext-access/ (accessed 8 Feb 2016).

- 7.Goddard M. Quality in and equality of access to healthcare services in England. University of York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankivsky O, Christoffersen A. Intersectionality and the determinants of health: a Canadian perspective. Crit Public Health 2008;18:271–83. 10.1080/09581590802294296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones AP, Haynes R, Sauerzapf V et al. Travel times to health care and survival from cancers in Northern England. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:269–74. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solberg LI, Crain AL, Sperl-Hillen JM et al. Effect of improved primary care access on quality of depression care. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:69–74. 10.1370/afm.426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerant A, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Primary care attributes and mortality: a national person-level study. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:34–41. 10.1370/afm.1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:457–502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Statistical digest of rural England 2013. London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Age UK. Later life in rural England. London: Age UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comino EJ, Davies GP, Krastev Y et al. A systematic review of interventions to enhance access to best practice primary health care for chronic disease management, prevention and episodic care. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:415 10.1186/1472-6963-12-415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakerman J, Humphreys JS, Wells R et al. Primary health care delivery models in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:276 10.1186/1472-6963-8-276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricketts TC, Goldsmith LJ. Access in health services research: the battle of the frameworks. Nurs Outlook 2005;53:274–80. 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer MS, Williford WO, McBride L et al. Perceived barriers to health care access in a treated population. Int J Psychiatry Med 2005;35:13–26. 10.2190/U1D5-8B1D-UW69-U1Y4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G et al. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford JA, Jones AP, Wong G et al. Improving access to high-quality primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas: a mixed method study protocol. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009104 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974;9:208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G et al. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med 2013;11:20 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broadhurst K. Engaging parents and carers with family support services: what can be learned from research on help-seeking? Child Fam Soc Work 2003;8:341–50. 10.1046/j.1365-2206.2003.00289.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovandzic M, Chew-Graham C, Reeve J et al. Access to primary mental health care for hard-to-reach groups: from ‘silent suffering’ to ‘making it work’. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:763–72. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addink RW, Bankart MJ, Murtagh GM et al. Limited impact on patient experience of access of a pay for performance scheme in England in the first year. Eur J Gen Pract 2011;17:81–6. 10.3109/13814788.2011.556720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buetow S, Adair V, Coster G et al. Qualitative insights into practice time management: does ‘patient-centred time’ in practice management offer a portal to improved access? Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:981–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimsmo A, Siem H. Factors affecting primary health care utilization. Fam Pract 1984;1:155–61. 10.1093/fampra/1.3.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pong RW, DesMeules M, Heng D et al. Patterns of health services utilization in rural Canada. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2011;31(Suppl 1):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Field KS, Briggs DJ. Socio-economic and locational determinants of accessibility and utilization of primary health-care. Health Soc Care Community 2001;9:294–308. 10.1046/j.0966-0410.2001.00303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allin S, Hurley J. Inequity in publicly funded physician care: what is the role of private prescription drug insurance? Health Econ 2009;18:1218–32. 10.1002/hec.1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckman A, Anell A. Changes in health care utilisation following a reform involving choice and privatisation in Swedish primary care: a five-year follow-up of GP-visits. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:452 10.1186/1472-6963-13-452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coles R, Watkins F, Swami V et al. What men really want: a qualitative investigation of men's health needs from the Halton and St Helens Primary Care Trust men's health promotion project. Br J Health Psychol 2010;15(Pt 4):921–39. 10.1348/135910710X494583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adamson J, Ben-Shlomo Y, Chaturvedi N et al. Ethnicity, socio-economic position and gender—do they affect reported health-care seeking behaviour? Soc Sci Med 2003;57:895–904. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00458-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tod AM, Read C, Lacey A et al. Barriers to uptake of services for coronary heart disease: qualitative study. BMJ 2001;323:214 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dingwall R, Robertson M. Aspects of illness. Behav Cogn Psychother 1978;6:22 10.1017/S014134730000505X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qu H, Platonova EA, Kennedy KN et al. Primary care patient satisfaction segmentation. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2011;24:564–76. 10.1108/09526861111160599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arksey H, Jackson K, Wallace AS et al. Access to health care for carers: barriers and interventions. In: National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO). London: NCCSDO, 2003. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/pdf/access.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bentley JM. Barriers to accessing health care: the perspective of elderly people within a village community. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:9–21. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00028-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shipman C, White S, Gysels M et al. Access to care in advanced COPD: factors that influence contact with general practice services. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:273–8. 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner K, Chapple A. Barriers to referral in patients with angina: qualitative study. BMJ 1999;319:418–21. 10.1136/bmj.319.7207.418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrig-Chiello P, Perrig WG, Stähelin HB. Health control beliefs in old age—relationship with subjective and objective health, and health behaviour. Psychol Health Med 1999;4:83–94. 10.1080/135485099106423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebrahim S. Ethnic elders. BMJ 1996;313:610–13. 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dixon-Wood M, Kirk D, Agarwal S et al. Vulnerable groups and access to health care: a critical interpretive review. In: National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO). London: NCCSDO, 2005. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1210-025_V01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camillo P. Understanding the culture of primary health care: implications for clinical practice. J N Y State Nurses Assoc 2004;35:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calnan M. Are older people still grateful? Age Ageing 2003;32:125–6. 10.1093/ageing/32.2.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mazza D, Shand LK, Warren N et al. General practice and preventive health care: a view through the eyes of community members. Med J Aust 2011;195:180–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bosma H, Schrijvers C, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and importance of perceived control: cohort study. BMJ 1999;319:1469–70. 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brabyn L, Barnett R. Population need and geographical access to general practitioners in rural New Zealand. N Z Med J 2004;117:U996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon J, Welch N. Researching the rural-metropolitan health differential using the ‘social determinants of health’. Aust J Rural Health 2000;8:254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Auchincloss AH, Van Nostrand JF, Ronsaville D. Access to health care for older persons in the United States: personal, structural, and neighborhood characteristics. J Aging Health 2001;13:329–54. 10.1177/089826430101300302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jinks C, Ong BN, O'Neill T. “Well, it's nobody's responsibility but my own.” A qualitative study to explore views about the determinants of health and prevention of knee pain in older adults. BMC Public Health 2010;10:148 10.1186/1471-2458-10-148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bosma H, van de Mheen HD, Mackenbach JP. Social class in childhood and general health in adulthood: questionnaire study of contribution of psychological attributes. BMJ 1999;318:18–22. 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McNiece R, Majeed A. Socioeconomic differences in general practice consultation rates in patients aged 65 and over: prospective cohort study. BMJ 1999;319:26–8. 10.1136/bmj.319.7201.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pescosolido BA. Advances in medical sociology. JAI Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moskowitz D, Lyles CR, Karter AJ et al. Patient reported interpersonal processes of care and perceived social position: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:392–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bryant LL, Corbett KK, Kutner JS. In their own words: a model of healthy aging. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:927–41. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00392-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horner SD, Ambrogne J, Coleman MA et al. Traveling for care: factors influencing health care access for rural dwellers. Public Health Nurs 1994;11:145–9. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1994.tb00393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campbell JL. Patients’ perceptions of medical urgency: does deprivation matter? Fam Pract 1999;16:28–32. 10.1093/fampra/16.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson JE, Weinert C, Richardson JK. Rural residents’ use of cardiac rehabilitation programs. Public Health Nurs 1998;15: 288–96. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1998.tb00352.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goodridge D, Hutchinson S, Wilson D et al. Living in a rural area with advanced chronic respiratory illness: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:54–8. 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathieson J, Popay J, Enoch E et al. Social exclusion: meaning, measurement and experience and links to health inequalities: a review of literature (WHO Social Exclusion Knowledge Network Background Paper 1). In: WHO, ed. Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University, 2008. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/media/sekn_meaning_measurement_experience_2008.pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freij M, Weiss L, Gass J et al. “Just like I'm saving money in the bank”: client perspectives on care coordination services. J Gerontol Soc Work 2011;54:731–48. 10.1080/01634372.2011.594490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birch S, Eyles J, Newbold KB. Equitable access to health care: methodological extensions to the analysis of physician utilization in Canada. Health Econ 1993;2:87–101. 10.1002/hec.4730020203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bossuyt N, Van den Block L, Cohen J et al. Is individual educational level related to end-of-life care use? Results from a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Belgium. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1135–41. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Underwood SM, Hoskins D, Cummins T et al. Obstacles to cancer care: focus on the economically disadvantaged. Oncol Nurs Forum 1994;21:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lamb J, Bower P, Rogers A et al. Access to mental health in primary care: a qualitative meta-synthesis of evidence from the experience of people from ‘hard to reach’ groups. Health (London) 2012;16:76–104. 10.1177/1363459311403945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raymond M, Iliffe S, Kharicha K et al. Health risk appraisal for older people 5: self-efficacy in patient-doctor interactions. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2011;12:348–56. 10.1017/S1463423611000296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Comber AJ, Brunsdon C, Radburn R. A spatial analysis of variations in health access: linking geography, socio-economic status and access perceptions. Int J Health Geogr 2011;10:44 10.1186/1476-072X-10-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bennett KJ, Baxley EG. The effect of a carve-out advanced access scheduling system on no-show rates. Fam Med 2009;41: 51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogowski J, Freedman VA, Wickstrom SL et al. Socioeconomic disparities in medical provider visits among Medicare managed care enrollees. Inquiry 2008;45:112–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drummond N, McConnachie A, O'Donnell CA et al. Social variation in reasons for contacting general practice out-of-hours: implications for daytime service provision? Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:460–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheung PT, Wiler JL, Lowe RA et al. National study of barriers to timely primary care and emergency department utilization among Medicaid beneficiaries. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:4–10.e2. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roos NP, Mustard CA. Variation in health and health care use by socioeconomic status in Winnipeg, Canada: does the system work well? Yes and no. Milbank Q 1997;75:89–111. 10.1111/1468-0009.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thommasen HV, Tatlock J, Elliott R et al. Review of salaried physician visits in a rural remote community—Bella Coola Valley. Can J Rural Med 2006;11:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choi N. Relationship between health service use and health information technology use among older adults: analysis of the US National Health Interview Survey. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e33 10.2196/jmir.1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goodall K, Ward P, Newman L. Use of information and communication technology to provide health information: what do older migrants know, and what do they need to know? Qual Prim Care 2010;18:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morgan CL, Beerstecher HJ. Satisfaction, demand, and opening hours in primary care: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e498–507. 10.3399/bjgp11X588475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jatrana S, Crampton P. Primary health care in New Zealand: who has access? Health Policy 2009;93:1–10. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Turnbull J, Martin D, Lattimer V et al. Does distance matter? Geographical variation in GP out-of-hours service use: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:471–7. 10.3399/bjgp08X319431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Magan P, Alberquilla A, Otero A et al. Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions and quality of primary care: their relation with socioeconomic and health care variables in the Madrid regional health service (Spain). Med Care 2011;49: 17–23. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef9d13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mercer SW, Jani BD, Maxwell M et al. Patient enablement requires physician empathy: a cross-sectional study of general practice consultations in areas of high and low socioeconomic deprivation in Scotland. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2296-13-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moffatt S, White M, Stacy R et al. The impact of welfare advice in primary care: a qualitative study. Crit Public Health 2004;14:295–309. 10.1080/09581590400007959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dixon A, Le Grand J, Henderson J et al. Is the British National Health Service equitable? The evidence on socioeconomic differences in utilization. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12: 104–9. 10.1258/135581907780279549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cawston PG, Mercer SW, Barbour RS. Involving deprived communities in improving the quality of primary care services: does participatory action research work? BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:88 10.1186/1472-6963-7-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buetow S, Adair V, Coster G et al. Reasons for poor understanding of when and how to access GP care for childhood asthma in Auckland, New Zealand. Fam Pract 2002;19:319–25. 10.1093/fampra/19.4.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choi S. Longitudinal changes in access to health care by immigrant status among older adults: the importance of health insurance as a mediator. Gerontologist 2011;51:156–69. 10.1093/geront/gnq064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Morgan G, Mitchell C, Gallacher J. The perceptions of older people in Wales about service provision. Qual Prim Care 2011;19:365–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Videau Y, Saliba-Serre B, Paraponaris A et al. Why patients of low socioeconomic status with mental health problems have shorter consultations with general practitioners. J Health Serv Res Policy 2010;15:76–81. 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hoeck S, Van der Heyden J, Geerts J et al. Equity in GP and specialist contacts by older persons in Belgium. Int J Public Health 2013;58:593–602. 10.1007/s00038-012-0431-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010652supp.pdf (348.2KB, pdf)