Abstract

Objective

The Lebanese Multiple Sclerosis (LeMS) study aims to assess the influence of pregnancy and delivery on the clinical course of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Lebanese women.

Setting

This prospective multicentre study took place in three MS referral university medical centres in Lebanon.

Participants

Included were 29 women over 18 years who had been diagnosed with MS according to the McDonald criteria, and became pregnant between 1995 and 2015. Participating women should have stopped treatment 3 months before conception and become pregnant after the onset of MS. Women were followed up from 1 year preconceptionally and for 4 years postpartum.

Main outcome measures

The annualised relapse rates per participant during each 3-month period during pregnancy and each year postpartum were compared with the relapse rate during the year before pregnancy using the paired two-tailed t test. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant for all analyses (95% CI).

Results

64 full-term pregnancies were recorded. All pregnancies (100%) resulted in live births, with no complications or other diseases. In comparison with the prepregnancy year, in which the mean relapse rate±SE was 0.17±0.07, there was a significant reduction in the relapse rate during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum (p=0.02), but an increase in the rate in the second year postpartum (0.21±0.08). Thereafter, from the third year postpartum through the following fourth year, the annualised relapse rate fell slightly but did not differ from the annualised relapse rate recorded in the prepregnancy year (0.17±0.07).

Conclusions

Pregnancy in Lebanese women with MS does not seem to increase the risk of complications. No relapses were observed during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum; however, relapses rebounded in the second year postpartum, and over the long term, returned to the levels that preceded pregnancy.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Relapse, Management, Outcomes, Interferon beta

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to analyse pregnancy related issues in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) that has been conducted in Lebanon and the Middle East and North Africa region.

All women were primiparous, had planned for the pregnancies, had stopped treatment 3 months before conception, did not smoke or drink alcohol or use drugs, reported no pregnancy or delivery complications, no birth defects or diseases postpartum, and were capable of breastfeeding.

The women served as their own controls because matching a cohort of pregnant women with MS with a cohort of women with MS who did not become pregnant would have been difficult.

The LeMS study is unique in the sense that it was the first to demonstrate that relapses disappeared completely during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum.

The sample size of our study may have contributed to the lack of significant differences in some of the outcomes.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system. Individuals diagnosed with MS are usually young women of childbearing age.1 Therefore, pregnancy-related issues, including childbirth and neonatal health, have become a concern for MS professionals and patients. Until the end of the 20th century, women with MS were discouraged from contemplating pregnancy due to the false belief that pregnancy would worsen the overall disease course.2–7 Furthermore, concerns about the progression of neurological disability over time affected family planning choices.8 Women with MS were naturally fretful as to how pregnancy would affect their disease, how the disease might modify pregnancy outcomes, and in particular, how the disease or the medications they were taking could affect the fetus.9 As a result of the 1998 publication of the first large prospective study of pregnancy and MS,10 family planning and counselling recommendations for women with MS radically changed, and many women have been able to fulfil their desire for motherhood. During this same time period, treatment options for MS accelerated and several disease-modifying drugs for MS entered the market.9

The cause of MS is unknown, but susceptibility to the disease is believed to be co-influenced by genetic and environmental factors.1 The risk of MS in children with one parent with MS is 1–3%,11 and 6–12% for children whose both parents have MS.12 13 However, the overall risk remains low, and having MS should not discourage patients with MS from having a child.

Until now, no studies analysing pregnancy and birth outcomes in women with MS have been carried out in Lebanon or in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region; the evolution of MS during pregnancy in the MENA region is largely unknown. Therefore, the objective of the Lebanese multiple sclerosis (LeMS) study is to explore pregnancy, labour and delivery course, and the birth outcomes in Lebanese women with MS.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective multicentre study of women from three MS referral centres in Lebanon. Information on women diagnosed with definite MS who became pregnant after the onset of the disease between 1995 and 2015 was collected through interviews. All women gave informed consent after they agreed to participate in the study.

Participants

Women aged over 18 years were recruited in the study. To be included, women had to have clinically diagnosed definite MS according to the 2010 McDonald criteria, clinical and para-clinical tests, and quantitative or qualitative abnormalities in immunoglobulins in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In addition, they had to have become pregnant after the onset of MS. The 2010 McDonald criteria allowed for a more rapid diagnosis of MS, with equivalent or improved specificity and/or sensitivity compared with the past criteria.14 It also clarified and simplified the diagnostic process with fewer required MRI. Only women who were deemed mentally competent were eligible for participation in the study.

Assessment

Before pregnancy, each new relapse—defined as showing a neurological dysfunction lasting longer than 24 h—was recorded and confirmed by a neurological examination. Treatment was prescribed if the relapse caused disability. During pregnancy, women were seen by a neurological specialist at 9–12 weeks and 26–29 weeks of gestation, and at 4–6 weeks and 10–12 weeks postpartum; these women were later followed for up to 4 years. Information on neurological conditions was collected by interviewing the women at each visit, and by telephone in case of any neurological event; obstetrical data were obtained by interviewing the women and reviewing the medical record. In-person interviews were used in this study despite the limitation of requiring a person to conduct the interview because these provide an opportunity for clarifying questions the woman could not otherwise understand.

Demographic and outcome measures

The data collected were as follows: (1) demographic and MS-related variables: age at MS onset; level of education; marital status; type of MS (relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS, primary progressive MS, and progressive-relapsing MS); and mean annualised relapse rate before, during, and after pregnancy (calculated as the ratio between the number of relapses experienced by each woman and the number of years for each period); (2) pregnancy-related variables: age during pregnancy; number of pregnancies after the onset of MS; history of smoking, alcohol, and drug use during pregnancy; history of relapses before, during, and after pregnancy; treatment before, during and after pregnancy; vitamin D3, magnesium, antidepressant and co-enzyme Q-10 supplementation; gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM); infections; preeclampsia; and preterm and post-term infants; (3) delivery-related variables: induction of labour, instrumental delivery, epidural and general anaesthesia, frequency of caesarean sections and normal vaginal deliveries; and (4) infant-related variables: mean gestational age, mean birth weight, low birth weight status, high birth weight status, birth defects or other diseases; and history of breastfeeding.

Statistical analysis

The relapse rates for each woman during each trimester of pregnancy and the 3 years postpartum were compared with the relapse rate during the year before pregnancy by means of paired two-tailed t tests. The paired t test was used as it calculates the difference within each before-and-after pair of measurements, determines the mean of these changes and reports whether this mean of differences is statistically significant. The effects of other demographic, pregnancy and infant-related variables on the course of MS were analysed using logistic regression, as these were thought to be associated with the presence or absence of a relapse in the postpartum phase. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant for all analyses (95% CI). All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows software V.23 (IBM SPSS, 2015).

Results

There were 29 women with definite MS who met the inclusion criteria. All of them agreed to participate in the study. We identified 64 pregnancies that had occurred since MS onset.

Demographic and MS characteristics

The mean age±SD of MS onset was 23±3.4 years (range=(16–34)). All (100%) had RRMS. Diagnosis was made using the 2010 McDonald criteria, MRI, and CSF studies. A total of 21 women (72.4%) were married and presenting for pregnancy consultation, and 8 (27.6%) were engaged to be married and were receiving consultation on the potential for starting a family. The complete profile of the women is displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the women in the LeMS study (N=29)

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean age at MS onset | 23 years |

| Mean age at pregnancy onset | 26.6 years |

| Level of education | |

| High school | 21 (72.4) |

| Undergraduate | 8 (27.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Engaged | 8 (27.6) |

| Married | 21 (72.4) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 2 (6.9) |

| Hypertension | 3 (10.3) |

| MS lesions | |

| Brain | 29 (100) |

| Brain and cervical spine | 7 (24.1) |

| MS diagnosis | |

| MRI | 29 (100) |

| CSF and oligoclonal positive | 26 (89.7) |

| CSF and oligoclonal not performed | 3 (10.3) |

| Pregnancies after MS onset | |

| One | 4 (13.8) |

| Two | 15 (51.7) |

| Three | 10 (34.5) |

| Supplements taken during pregnancy | |

| Vitamin D3 | 21 (72.4) |

| Co-enzyme Q-10 | 20 (69) |

| Fluoxetine | 11 (37.9) |

| Magnesium sulfate | 21 (72.4) |

| Delivery method | |

| Normal vaginal | 23 (79.3) |

| Caesarean | 6 (20.7) |

| Epidural anaesthesia | 21 (72.4) |

| Length of breastfeeding (days) | |

| 21–35 | 6 (20.7) |

| 93–255 | 23 (79.3) |

| Treatment after pregnancy | |

| Resumed after 11–14 months | 22 (75.9) |

| Stopped indefinitely | 7 (24.1) |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; LeMS, the Lebanese Multiple Sclerosis study; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Pregnancy characteristics

Women had a mean age±SD of 26.6±3.8 years during pregnancy (range=(19–43)). Four women (13.8%) had one pregnancy after the onset of MS, 15 (51.7%) had two, and 10 (34.5%) had three pregnancies. All of these women (100%) were primiparous when they agreed to participate in the study. All of the pregnancies (100%) were planned pregnancies. None of the women smoked, drank alcohol or used drugs during pregnancy. Three pregnancies (4.7%) occurred in women who had preGDM and another three pregnancies (4.7%) occurred in women who had chronic hypertension. None of the women had reported urinary tract infections or any other infections during pregnancy. No ectopic pregnancies occurred. No cholecystitis, gestational diabetes or abortions occurred. No preeclampsia or placental disorders were reported. All of the pregnancies were full term. All pregnancies (100%) resulted in live births. None of the women got pregnant in the 4 years postpartum. We found no evidence of an association between any of the pregnancy characteristics and other known risk factors.

Treatment

Before pregnancy, 23 women (79.3%) were on intramuscular interferon β-1a and received one injection per week. The other 6 women (20.7%) were on subcutaneous interferon β-1a and received three injections per week. The treatment modality differed by physician and patient preference. Treatment was stopped 3 months before conception for all women.

In 44 of 64 pregnancies (68.6%), women took vitamin D3 and magnesium supplements (200 mg, once daily). In 41 pregnancies (64.1%), the women took co-enzyme Q-10 supplements. Low dose of fluoxetine (10 mg, once daily) was prescribed in 22 pregnancies (34.4%).

Following delivery, the mother’s condition was neurologically assessed, and the woman was asked to continue without treatment in order to breastfeed. After 11–14 months, 22 women (75.9%) resumed the treatment regimen that they were using in the prepregnancy phase. However, 7 women (24.1%) decided on their own to stop treatment indefinitely; these women had 19 pregnancies (29.7%) with no complications and were able to lead normal lives.

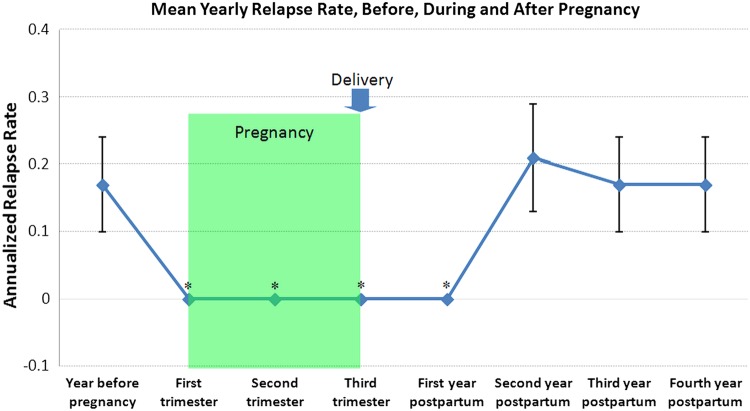

MS relapses

The annualised relapse rates in the years before, during, and after pregnancy are presented in table 2 and figure 1. In comparison with the prepregnancy year, in which the mean±SE relapse rate was 0.17±0.07, there was a significant reduction in the relapse rate during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum (p=0.02), but an increase in the relapse rate the second year after delivery (0.21±0.08). Thereafter, from the third postpartum year through the following fourth year, the annualised relapse rate fell slightly but did not differ from the annualised relapse rate recorded in the prepregnancy year (0.17±0.07).

Table 2.

Relapses of multiple sclerosis during pregnancy among 29 Lebanese women

| Period | Number of women* | Number of relapses | Rate of relapse/woman/year† | p Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year before pregnancy | 29 | 5 | 0.17 (0.03 to 0.32) | – |

| Pregnancy | ||||

| First trimester | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Second trimester | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Third trimester | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Postpartum | ||||

| First year | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Second year | 29 | 6 | 0.21 (−0.12 to 0.04) | 0.32 |

| Third year | 29 | 5 | 0.17 (0.03 to 0.32) | – |

| Fourth year | 29 | 5 | 0.17 (0.03 to 0.32) | – |

*All women stopped interferon β 1-a treatment 3 months before conception.

†Values are means (95% CI).

‡p Values are for the comparison with the relapse rate during the year before pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Annualised relapse rate in the year before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and in the four years after delivery among the 29 women with MS (vertical bars represent means and standard errors of means; * signifies p<0.05 for annualised relapse rate when compared to the year before pregnancy). MS, multiple sclerosis.

Among the 29 women with 64 live births, none had relapses during pregnancy or in the first year postpartum. Six (21%) had one relapse each in the second year postpartum. Five (17%) had one relapse each in the third and fourth years postpartum, respectively. None of the patients required prophylactic relapse treatment after labour.

We did not find any evidence of an association between relapses before pregnancy and relapses during the second, third or fourth year of the postpartum period. We did not find evidence of any association of post-labour MS relapses with other potential risk factors (age, breastfeeding, MS onset and duration, treatment before pregnancy, epidural anaesthesia or any other factor).

Delivery and characteristics of newborns

There were 12 planned caesarean deliveries (18.8%). Forceps and vacuum were not used in any of the cases. Normal vaginal delivery was achieved in 52 pregnancies (81.2%). Epidural anaesthesia was used in 35 of 52 normal vaginal deliveries (67.3%), and in all of the 12 caesarean deliveries (100%). General anaesthesia was not used in any of the cases. All 64 pregnancies resulted in live births with no malformations or congenital anomalies. The mean full-term birth weight was 3200 g (ranging from 2000 to 4250 g). There was only one newborn (1.6%) who was small for gestational age (<10th centile for gestational age).

Breastfeeding

All of the newborns (100%) were breast-fed. The mean duration of breastfeeding was 157 days (ranging from 21 to 255 days). Forty-eight newborns (75%) were breast-fed for a period ranging from 93 to 255 days. Sixteen newborns (25%) were breast-fed for a period between 21 and 35 days.

Discussion

This is the first study to analyse pregnancy-related issues in patients with MS conducted in Lebanon and the MENA region. The frequency of relapses decreased significantly during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum compared with the rate estimated in the year before pregnancy. Relapse rates rebounded in the second year postpartum, and returned to the prepregnancy rate in the third and fourth years postpartum. In line with other studies in the literature,10 15–19 all the women in our study had RRMS. However, our sample was unique in the sense that all women did not smoke, drink alcohol or use drugs. All women were primiparous, had planned for the pregnancies, had stopped treatment 3 months before conception, reported no pregnancy or delivery complications, had no birth defects or diseases postpartum and were capable of breastfeeding. Our study does not show any unfavourable pregnancy outcomes associated with MS.

Comparison to similar studies

Similar to other studies in the literature,10 15–19 the relapse rate of MS decreased significantly during pregnancy. However, while other studies reported a significant decrease in relapse rates in the third trimester of pregnancy only,10 15–18 our study reported a significant decrease in relapse rates in all three trimesters of pregnancy. Additionally, in contrast to studies showing that relapse rates rebounded significantly in the first trimester postpartum,10 15–17 our study was the first to demonstrate a significant decrease in relapse rates in the first year postpartum and a non-significant rebound in the second year postpartum when compared to the prepregnancy rate. Similar to other studies,10 15–17 20 21 over the long-term postpartum, the relapse rates eventually returned to prepregnancy rates.

The relapse rate in our study ranged between 0 and 0.21, which is the lowest among all the previous similar studies. Confavreux et al10 reported relapse rates that ranged between 0.20 and 1.20, Fernandez Liguori et al16 had relapse rates ranging between 0.04 and 0.82, Jalkanen et al17 reported relapse rates that ranged between 0.40 and 1.40, Salemi et al18 had relapse rates ranging between 0.36 and 0.72, and Fragoso et al19 reported relapse rates that ranged between 0.29 and 1.37.

Among women in this study, interferon β 1-a treatment was stopped 3 months before conception as a precautionary measure to avoid pregnancy complications or birth defects. Fernandez Liguori et al,16 van Walderveen et al21 and Sandberg-Wollheim et al22 reported that high doses of interferon β increased spontaneous abortions and incidence of major birth defects (eg, Down syndrome, hydrocephalus, abnormalities in the X chromosome, etc). Several other studies suggest that, whenever possible, interferon β treatment should be discontinued prior to conception.21–28 However, similar women in other studies continued to receive treatment modalities throughout pregnancy.10 15–19

Initially, vitamin D was given as a supplement to address the paucity women may suffer from during pregnancy,29 and to attend to the vitamin D deficiency in the general Lebanese population.30 More recent studies have also shown that maintaining adequate levels of vitamin D during pregnancy might have a protective effect and lower the risk of developing postpartum relapses.31

Psychological support was crucial in maintaining the mental well-being of the mother.32 Some women exhibited signs of anxiety and depression. Thus, after weighing risks and benefits, they were given fluoxetine in low doses to improve their mental health. Magnesium sulfate was also supplemented to support the pregnancy, avoid potential complications, and further improve the mental well-being of the women.33 Co-enzyme Q-10 was given to enhance fertility and egg quality.34–36

According to our study, MS does not seem to increase the risk of a caesarean delivery or require the use of instrumentation. In contrast, Dahl et al37 and Jalkanen et al17 reported a high level of planned caesarean deliveries and instrumental deliveries in patients with MS. In line with previous studies,10 15 38 epidural anaesthesia was not associated with an increase in postpartum relapses.

Most similar studies reported complications during and after pregnancy.10 15–19 Our study, however, reported no obstetric complications; all of the pregnancies were full term and resulted in live births.

As all of the women in our sample breast-fed their babies, we did not find a significant relationship between the number of days spent breastfeeding and relapse. Similarly, other studies have also not found a significant association between breastfeeding and relapses.39–41 In practice, however, strong evidence supports the statement that breastfeeding does not increase the risk of postpartum relapse—it could even be protective.41 42 Confavreux et al10 reported that women who chose to breastfeed experienced significantly fewer relapses and had milder disability scores in the year after pregnancy in comparison with women who chose not to breastfeed. As medications used for the treatment of MS may enter breast milk, these were normally withheld during breastfeeding. The decision of whether to resume a treatment postpartum was weighed against the potential benefits of breastfeeding.

Strengths and limitations

Careful prospective follow-up of women ensured good data quality and up-to-date information in the present study. The women served as their own controls because matching a cohort of pregnant women with MS with a cohort of women with MS who did not become pregnant would have been difficult. Our results are also in accordance with studies that have shown that MS does not seem to have a deleterious effect on the course and outcome of pregnancy or delivery.10 15–19 Furthermore, the LeMS study is unique in the sense that it was the first to demonstrate that relapses disappeared completely during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum. Conversely, the sample size of our study may have contributed to the lack of significant differences in some of the outcomes.

Future research

A better understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying this pregnancy-related decrease in disease activity could lead to new and effective therapeutic strategies in MS. The reasons for the decreased relapse activity during pregnancy are not entirely clear, but factors such as increased oestrogen levels before delivery, and the immunosuppressive state of the women during pregnancy are likely to be of importance.43–45 The role of breastfeeding and its potential effect on relapses postpartum can also be explored; we hypothesise that high levels of prolactin in women with MS postpartum who are breastfeeding play a protective role. We also believe that the women's genetics, lifestyle, mental well-being, high vitamin D3, co-enzyme Q-10, and magnesium sulfate supplementations may generate a protective effect against relapses.

Conclusions and implications

In line with the previous conception studies, pregnancies in Lebanese women with MS do not seem to pose a risk of complications. No relapses were observed during pregnancy and in the first year postpartum; however, relapses rebounded in the second year postpartum, and over the long term, returned to the levels that preceded pregnancy. The characteristics and lifestyle of the women in the study can serve as a model to other women with MS who seek motherhood. Furthermore, the medical management presented in the LeMS study can be a guide to physicians in their future dealings with similar cases.

Footnotes

Contributors: JF and YF designed the study, collected the data, carried out the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the analysis of the results. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YF is the primary investigator and guarantor of the study.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Medical Sciences, Lebanese University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Pietrangelo A, Higuera V. Multiple Sclerosis by the Numbers: Facts, Statistics, and You. Healthline 2015. http://www.healthline.com/health/multiple-sclerosis/facts-statistics-infographic

- 2.Douglass LH, Jorgensen CL. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1948;3:797–8. 10.1097/00006254-194812000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tillman AJ. The effect of pregnancy on multiple sclerosis and its management. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 1950;28:548–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeney WJ. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1958;1:137–48. 10.1097/00003081-195803000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchinson M. Pregnancy in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1993;56:1043–5. 10.1136/jnnp.56.10.1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadovnick A. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1994;51:1120 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540230058013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudick R. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1995;52:849–50. 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540330019003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korn-Lubetzki I, Kahana E, Cooper G et al. . Activity of multiple sclerosis during pregnancy and puerperium. Ann Neurol 1984;16:229–31. 10.1002/ana.410160211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11:280–9. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM et al. . Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med 1998;339:285–91. 10.1056/NEJM199807303390501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M, O'Brien P. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2008;79:1308–11. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.116947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor PW, Goodman A, Kappos L et al. . Disease activity return during natalizumab treatment interruption in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2011;76:1858–65. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e7c8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Killestein J, Vennegoor A, Strijbis EM et al. . Natalizumab drug holiday in multiple sclerosis: poorly tolerated. Ann Neurol 2010;68:392–5. 10.1002/ana.22074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B et al. . Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. 10.1002/ana.22366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M et al. . Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain 2004;127:1353–60. 10.1093/brain/awh152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández Liguori N, Klajn D, Acion L et al. . Epidemiological characteristics of pregnancy, delivery, and birth outcome in women with multiple sclerosis in Argentina (EMEMAR study). Mult Scler 2009;15:555–62. 10.1177/1352458509102366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jalkanen A, Alanen A, Airas L. Pregnancy outcome in women with multiple sclerosis: results from a prospective nationwide study in Finland. Mult Scler 2010;16:950–5. 10.1177/1352458510372629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salemi G, Callari G, Gammino M et al. . The relapse rate of multiple sclerosis changes during pregnancy: a cohort study. Acta Neurol Scand 2004;110:23–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fragoso Y, Finkelsztejn A, Comini-Frota E et al. . Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: the initial results from a Brazilian database. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr 2009;67:657–60. 10.1590/S0004-282X2009000400015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA et al. . Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Ann Neurol 1996;39:285–94. 10.1002/ana.410390304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Walderveen MA, Tas MW, Barkhof F et al. . Magnetic resonance evaluation of disease activity during pregnancy in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1994;44:327–9. 10.1212/WNL.44.2.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandberg-Wollheim M, Frank D, Goodwin TM et al. . Pregnancy outcomes during treatment with interferon beta-1a in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2005;65:802–6. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168905.97207.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boskovic R, Wide R, Wolpin J et al. . The reproductive effects of beta interferon therapy in pregnancy: a longitudinal cohort. Neurology 2005;65:807–11. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180575.77021.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwosh E, Guimond C, Sadovnik AD. Reproductive counseling in MS: a guide for healthcare professionals. Int MS J 2003;10:67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyle P, Johnson K, Padro L et al. . Pregnancy outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with glatiramer acetate (Copaxone). Neurology 2003;60:A60 10.1212/01.WNL.0000071227.23769.9E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Las Heras V, De Andrés C, Téllez N et al. . Pregnancy in multiple sclerosis patients treated with immunomodulators prior to or during part of the pregnancy: a descriptive study in the Spanish population. Mult Scler 2007;13:981–4. 10.1177/1352458507077896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellwig K, Brune N, Haghikia A et al. . Reproductive counselling, treatment and course of pregnancy in 73 German MS patients. Acta Neurol Scand 2008;118:24–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS et al. . Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler 2011;17:423–30. 10.1177/1352458510394610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jalkanen A, Kauko T, Turpeinen U et al. . Multiple sclerosis and vitamin D during pregnancy and lactation. Acta Neurol Scand 2015;131:64–7. 10.1111/ane.12306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lips P, Hosking D, Lippuner K et al. . The prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy amongst women with osteoporosis: an international epidemiological investigation. J Intern Med 2006;260:245–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01685.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etemadifar M, Janghorbani M. Efficacy of high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in vitamin D deficient pregnant women with multiple sclerosis: preliminary findings of a randomized-controlled trial. Iran J Neurol 2015;14:67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayoub F, Fares Y, Fares J. The psychological attitude of patients toward health practitioners in Lebanon. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7:452–8. 10.4103/1947-2714.168663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueda A, Kondoh E, Kawasaki K et al. . Magnesium sulphate can prolong pregnancy in patients with severe early-onset preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1114091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannubilo SR, Tiano L, Ciavattini A et al. . Amniotic coenzyme q10: is it related to pregnancy outcomes? Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;21:1582–6. 10.1089/ars.2014.5936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bentov Y, Casper RF. The aging oocyte—can mitochondrial function be improved? Fertil Steril 2013;99:18–22. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bentov Y, Esfandiari N, Burstein E et al. . The use of mitochondrial nutrients to improve the outcome of infertility treatment in older patients. Fertil Steril 2010;93:272–5. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahl J, Myhr KM, Daltveit AK et al. . Pregnancy, delivery, and birth outcome in women with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2005;65:1961–3. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188898.02018.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pastò L, Portaccio E, Ghezzi A et al. . Epidural analgesia and cesarean delivery in multiple sclerosis post-partum relapses: the Italian cohort study. BMC Neurol 2012;12:165 10.1186/1471-2377-12-165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller DH, Fazekas F, Montalban X et al. . Pregnancy, sex and hormonal factors in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014;20:527–36. 10.1177/1352458513519840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, Hakiki B et al. . Breastfeeding is not related to postpartum relapses in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2011;77:145–50. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318224afc9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langer-Gould A, Huang SM, Gupta R. Exclusive breastfeeding and the risk of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2009;66:958–63. 10.1001/archneurol.2009.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hellwig K, Haghikia A, Rockhoff M et al. . Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy: experience from a nationwide database in Germany. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2012;5:247–53. 10.1177/1756285612453192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes SE, Spelman T, Gray OM et al. . Predictors and dynamics of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014;20:739–46. 10.1177/1352458513507816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saraste MH, Kurki T, Airas LM. Postpartum activation of multiple sclerosis: MRI imaging and immunological characterization of a case. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:98–9. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paavilainen T, Kurki T, Parkkola R et al. . Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain used to detect early post-partum activation of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:1216–21. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]