Abstract

Objectives

Primary care physicians (PCPs) should prescribe faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) or colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening based on their patient's values and preferences. However, there are wide variations between PCPs in the screening method prescribed. The objective was to assess the impact of an educational intervention on PCPs’ intent to offer FIT or colonoscopy on an equal basis.

Design

Survey before and after training seminars, with a parallel comparison through a mailed survey to PCPs not attending the training seminars.

Setting

All PCPs in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland.

Participants

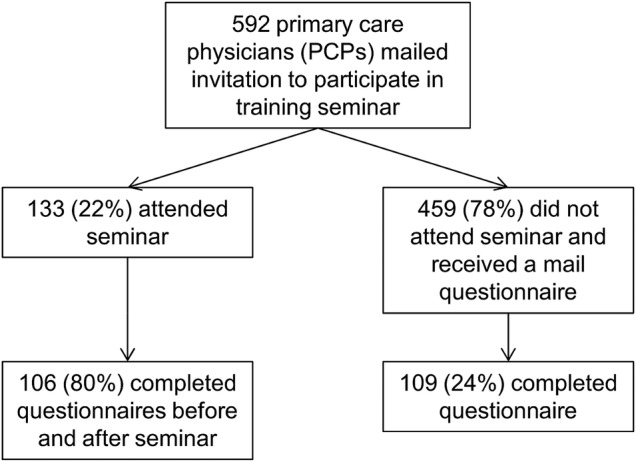

Of 592 eligible PCPs, 133 (22%) attended a seminar and 106 (80%) filled both surveys. 109 (24%) PCPs who did not attend the seminars returned the mailed survey.

Intervention

A 2 h-long interactive seminar targeting PCP knowledge, skills and attitudes regarding offering a choice of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening options.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was PCP intention of having their patients screened with FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions (between 40% and 60% each). Secondary outcomes were the perceived role of PCPs in screening decisions (from paternalistic to informed decision-making) and correct answer to a clinical vignette.

Results

Before the seminars, 8% of PCPs reported that they had equal proportions of their patients screened for CRC by FIT and colonoscopy; after the seminar, 33% foresaw having their patients screened in equal proportions (p<0.001). Among those not attending, there was no change (13% vs 14%, p=0.8). Of those attending, there was no change in their perceived role in screening decisions, while the proportion responding correctly to a clinical vignette increased (88–99%, p<0.001).

Conclusions

An interactive training seminar increased the proportion of physicians with the intention to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The training seminars were organised within a statewide, organised screening programme.

All primary care physicians (PCP) in canton Vaud, Switzerland, were invited to attend the seminars. All those not attending were mailed a survey.

Twenty-two per cent of PCPs attended the seminars and 24% not attending returned the mails survey; there was no randomisation of PCPs to the intervention, thus limiting causal inference.

We only measured changes in intentions to prescribe, and hence verified prescription rates are needed.

Introduction

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) reduces CRC mortality and is widely recommended for age 50 years onwards.1 2 Each of the recommended methods for CRC screening have varying test characteristics;3 while colonoscopy has high sensitivity for both cancerous and precancerous lesions, allowing for screening every 10 years, it is invasive and carries a risk of bleeding and perforation.4 Faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) for occult blood on the other hand has lower sensitivity for precancerous adenomas, but is less costly, and can be performed at home without preparation and also has higher acceptability than colonoscopy.5–7 Studies have suggested that in real-world settings, the performance of FIT and colonoscopy for detecting cancers are equivalent, making both reasonable first-line choices for screening.6 8

In contexts where more than one reasonable choice exists, preferences become important.9 Some patients might prefer colonoscopy, thereby accepting a more burdensome screening modality than FIT; others might prefer FIT, thus accepting its reduced precision as compared to colonoscopy. Physicians, especially in the USA, have a clear preference for colonoscopy because of its greater sensitivity for and ability to remove precancerous adenomas and polyps.10 Extensive literature has revealed wide geographic variations in the use of preference-sensitive conditions (including CRC screening method)11 that are not explained by differences in patient preferences, but rather by physician preferences and local medical culture.12 These differences persist when looking at the level of individual physicians, and not just at the geographical areas.13 Shared decision-making (SDM) might help reduce these unacceptable variations by increasing patient participation in decisions.13 14 Patient’s preferences towards a screening modality are expected to vary between patients within primary care practice.7 Training physicians to identify their patient’s preferences might lead physicians who essentially prescribe their own preferred screening method to prescribe the screening method preferred by their patients and thereby, increase the variation of prescribed screening modality within their practice. Reducing the number of physicians who only prescribe one screening modality through preference diagnosis will in turn lead to reduced variation between practices.9

The Health Department of the canton of Vaud has recently decided to launch the first systematic, statewide, organised CRC screening programme in Switzerland that will offer both FIT and colonoscopy to the entire eligible population via a discussion with their primary care physician (PCP).15 The aims of the discussion with their PCP are to increase the number of citizens who take an active decision about CRC screening, and enable participants to choose between two screening methods within a SDM encounter with their PCP.15 A decision aid will be mailed informing citizens of the programme, the available screening modalities and encourage discussion with their PCP. Baseline surveys of PCPs in the canton suggest wide variations in baseline PCP preferences, with a predilection for colonoscopy.15 International literature suggests that physician preference for colonoscopy translates into recommendations to patients that are focused only on colonoscopy, with little mention of other screening modalities;10 16 this could have negative effects on patient participation and independence.7 10 17 18 SDM should contribute to reducing variation in care between individual practices.

We administered training seminars for PCPs from the Canton of Vaud prior to the beginning of the screening programme. The objectives of the seminar were to improve PCPs knowledge, provide skills and tools needed for SDM with patients, and change the attitudes of PCPs regarding the importance of incorporating patient preferences in CRC screening decisions (see online supplementary figure S1). We hypothesised that such an intervention would increase the number of PCPs who intend to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions, and engage in SDM.

bmjopen-2016-011086supp.pdf (254.8KB, pdf)

Methods

Study setting and participants

The canton of Vaud is in French-speaking Switzerland and has ∼ 740 000 inhabitants, of whom 180 000 are between 50 and 69 years. A systematic, organised, statewide CRC screening programme was launched in the canton in the fall of 2015, the first systematic CRC screening programme in Switzerland. Eligible citizens will receive an invitation letter and decision aid explaining the rationale for screening, and the choice of FIT and colonoscopy. They are encouraged to visit their PCP, who will discuss the screening and provide either a prescription for a FIT kit or referral for colonoscopy. The programme comes after a federal decision in 2013 to have screening colonoscopy and FIT be reimbursed by base, obligatory insurance packages;19 in the setting of a screening programme, an inclusion visit with their PCP, the screening test, and diagnostic colonoscopies after a positive FIT are all covered without deductible.

At the end of 2014, all PCPs registered to practice in the Canton of Vaud were invited to participate in one of five seminars held in January and February 2015 for the new CRC screening programme. The seminars were free of charge and offered Continuing Medical Education (CME) credits and free food. Those who had not been to one of these seminars were mailed an invitation at the end of February to attend an extra session on 24 March 2015 along with paper copies of the SDM materials described below, and a questionnaire regarding their CRC screening practices. Ethical approval was not required as we only collected anonymised data through questionnaires from physicians participating in the training session and practicing family physicians in the community, as specified by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health.20

Seminars

The seminar lasted 2 h. Multiple strategies were employed to achieve the educational objectives, including lectures, interactive elements and discussion, and the use of SDM tools (see online supplementary figure S1). The lectures summarised the epidemiology of CRC screening, follow-up of polyps, and the organisation of the screening programme and integrated interactive elements. First, we presented the variation among attending PCPs regarding their preferred screening modality (FIT vs colonoscopy) by using live polling (TurningPoint technology) along with other knowledge-based multiple choice questions.14 Second, we used a narrative presenting a patient choosing a FIT test and naming her reasons for choosing FIT rather than colonoscopy in an 8 min video of an ideal inclusion visit to the PCP office.21 Third, the video presented a role model of a physician actively going through the process of SDM; we used the suggested framework of Elwyn et al22 with three stages of SDM (choice talk, option talk and decision talk) that allow for information sharing by the physician and provide a safe space for patients to express their preferences. This process was followed by teach-back (having patients repeat back important information), which has been shown to improve retention, especially by patients with low health literacy.23 Finally, we used elements of risk communication to facilitate the understanding of PCPs of the pros and cons of screening. Communication materials were presented during the session and in context using the video; these included an evidence summary for PCPs (‘Decision Box’) based on the work of Giguere et al, and a decision aid based on current recommendations such as the use of multiple methods to present risk in natural frequencies using text, figures and a summary table (see online supplementary materials).24–27

Questionnaires

We used two paired anonymised questionnaires for the PCPs participating in the seminar, before and after the seminar. The questionnaires contained a total of 16 questions querying demographics (sex, age, practice characteristics and personal CRC screening history), screening modalities offered to their patients, preferred communication style, and a knowledge question about the appropriate indication for screening (see primary and secondary outcomes section below). We used a similar questionnaire for PCPs not participating, adapting the questions into a single questionnaire. PCPs not participating to the training had the opportunity to fill the questionnaire on paper or use an identical questionnaire online using the programme Survey Monkey.

Primary and secondary outcomes

We aligned our outcomes with our objectives (see online supplementary figure S1). The primary outcome was the increase in the proportion of PCPs answering that they intended to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in close to equal proportions. PCPs were asked before the seminar ‘During recent months, if you prescribed a CRC screening test, to what proportion of your patients did you prescribe each of these tests?’ Attendees filled the per cent of each option they currently prescribed on average (colonoscopy, FIT, FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, CT-scan, blood test, other method) and were supposed to arrive at 100% as a sum of the percentages. PCPs reporting that they offered colonoscopy and FIT between 40% and 60% of the time were considered to have offered the two tests in equal proportions. Both guaiac and immunological tests were considered as being a faecal occult blood test, and are referred here in the results as FIT testing, as FIT is the testing modality used by the new screening programme. At the end of the session, attendees were asked: ‘After the start of the screening programme, to what proportion of your patients do you intend on prescribing each of these tests?’ We aimed at capturing the variation in screening patterns between attending PCPs and the extent to which the programme altered these screening patterns. Several studies suggest that nearly equal proportions of patients prefer non-invasive to invasive modes of CRC screening.7 28 29

There were two secondary outcomes. First, we aimed at capturing whether the seminar was associated with a change in preferred communication style from paternalistic to informed decision-making.30 Before the session, we asked PCPs attending: ‘How are decisions made regarding CRC screening in your practice?’; four possible answers were: ‘I take decisions myself according to my understanding of the risks and benefits of screening’, ‘I take the decision myself with strong consideration of the patient's opinion’, ‘I take the decision with the patient on an equal basis’ and ‘The patient takes the decision according to his/her understanding of the risks and benefits of screening’. This same question was asked to PCPs not attending. At the end of the session, PCPs attending were queried on how they intended to approach decision-making after the start of the screening programme by using a similar adapted question. The second secondary outcome was the proportion correctly answering that an asymptomatic 54-year-old woman without a family history of CRC meets inclusion criteria for screening. Here again, PCP answers after the seminar were compared to the same PCPs’ answers before the training and non-attendees.

Statistical analyses

All questionnaires were completed by the physicians themselves and answers were extracted by one research assistant. Descriptive statistics were used for demographic characteristics. χ2 and t test statistics were used to compare physician characteristics, and responses between attendees and non-attendees. McNemar's test for paired data was used to compare answers from attendees before and after the seminar. Logistic regressions were used to identify predictors of a change in screening behaviours; we used generalised estimating equations (GEE) logistic regressions with an exchangeable correlation structure to take into account clustering of the data by participants. We first ran univariate logistic regressions with the change in screening behaviour as a binary outcome and participant's sex, diploma year, practice location and whether they attended the seminar as predictors. As only attending the seminar was significant with p<0.1 in univariate analyses, the primary analysis was univariate. A sensitivity analysis was performed using a model with all of the variables. All analyses were performed using STATA V.14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Results with a two-sided p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 592 PCPs registered to practice in the Canton of Vaud and invited to participate, 133 (22%) attended one of five seminars (figure 1) and of these, 106 (80%) completed both the before and after questionnaires. Of the 459 PCPs who had not participated in a seminar, 109 (24%) returned a questionnaire (table 1). Seminar attendees were more likely to be female, have completed their professional diploma more recently, and be in practice with at least one other PCP.

Figure 1.

Flow of study participants. PCP, primary care physicians.

Table 1.

Characteristics of primary care physician attendees and non-attendees in the seminars

| Attendees (n=106) | Non-attendees (n=109) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Women (%) | 38 (36%) | 23 (21%) | 0.014 |

| Age < 50 years (%) | 34 (32%) | 31 (28%) | 0.589 |

| Year of professional diploma (±SD) | 1989 (±10) | 1985 (±10) | 0.021 |

| Practice characteristics | |||

| Solo practice | 16 (15%) | 51 (47%) | <0.001 |

| 2 or more physicians in practice | 57 (54%) | 28 (26%) | |

| Missing | 33 (31%) | 30 (28%) | |

| Practice location | |||

| Urban | 91 (88%) | 80 (83%) | 0.384 |

| Rural | 12 (12%) | 16 (17%) | |

| Weekly work schedule | |||

| Fewer than 10 half-days per week | 7 (7%) | 34 (31%) | 0.256 |

| 10 or more half-days per week | 26 (25%) | 74 (69%) | |

| Missing | 73 (69%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Have already themselves undergone CRC screening | 50 (51%) | 58 (53%) | 0.696 |

| Screening test, for those who have undergone screening | |||

| Colonoscopy | 37 (74%) | 55 (95%) | |

| Stool-based test | 8 (16%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Baseline prescribing by screening modality | |||

| >60% colonoscopy | 64 (68%) | 61 (56%) | |

| >60% FIT/gFOBT | 19 (20%) | 17 (16%) | |

| Equal stool-based and colonoscopy | 8 (9%) | 14 (13%) | 0.311 |

Of those who have undergone CRC screening, 88% have had colonoscopy and 10% a stool-based test.

CRC, colorectal cancer; FIT, Faecal immunochemical test; FOBT, guaiac faecal occult blood test.

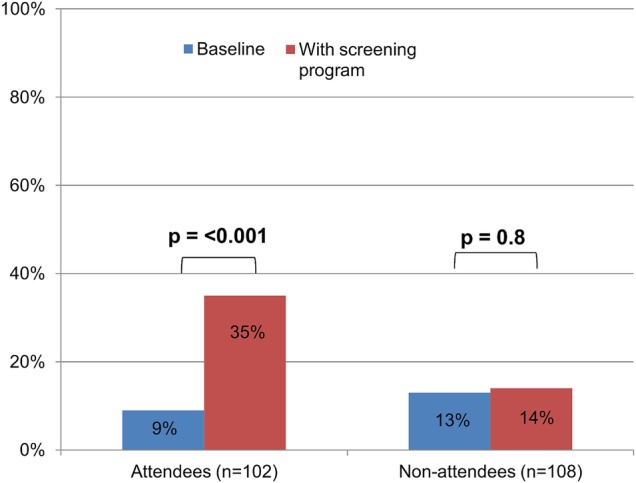

Figure 2 shows the number of PCPs prescribing FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions at baseline, and their intended prescribing after the implementation of the systematic screening programme. Among those who participated in the seminar, the proportion of PCPs to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions increased from 8% to 33% (RR: 4.1, 95% CI 2.2 to 7.7, p<0.001). We found no change between past and intended future prescribing among non-attendees (13–14%, p=0.8), and found a significant difference in intended future prescribing among participants and non-participants (33% vs 14%, p<0.001). We found a significant decrease in the number of PCPs offering only colonoscopy among attendees, while we found an increase among non-attendees (see online supplementary figures S2 and S3). Results from univariate models showed that only attendance to the course was significantly associated with a change in prescribing (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.37), while sex, year of diploma and practice location were not significant (p<0.1). In the sensitivity analyses, we included all of the variables in a multivariate model, and attending the course remained significant.

Figure 2.

Physicians prescribing stool-based testing and colonoscopy in similar proportions at baseline and intended future prescribing with the cantonal screening programme, stratified by those attending and not attending the seminar.

The proportion of physicians reporting that they take decisions regarding CRC together with their patients on an equal basis did not differ between attendees and non-attendees, and did not change after the seminar (figure 3A). The proportion of physicians correctly responding that a 54-year-old asymptomatic woman without risk factors is a candidate for CRC screening increased from 88% to 99% among those who attended the course (p<0.001), while there was no difference in baseline knowledge among those who did and did not attend the course (p=0.4) (figure 3B).

Figures 3.

(A) Proportion of physicians who report taking decisions regarding colorectal cancer screening decisions together with their patients on an equal basis, at baseline and after the seminar. (B) Proportion of physicians correctly responding to a clinical scenario regarding colorectal cancer screening indications, at baseline and after the seminar.

Discussion

We found a significant increase in the percentage of PCPs intending to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions before and after a seminar focused on increasing knowledge, teaching skills and changing attitudes on CRC screening. We did not find such a difference among PCPs who received paper training materials by mail, but did not attend the seminar. The seminar was not associated with a self-reported change in SDM communication style, and increased the percentage of PCPs correctly answering a clinical vignette on the indications for CRC screening.

While SDM has frequently been invoked as a way to decrease unwarranted variations in care,14 31 32 there is little literature about whether the implementation of SDM in physician training programmes can have an impact on variations in care. The use of patient decision aids alone appears to improve patient decision-making and decrease the use of certain invasive interventions;33 a recent systematic review, however, concluded that the implementation of SDM in daily practice is most effective when both patients and physicians are targeted.34 Several previous programmes have shown that physician training in SDM can have an impact on the prescription patterns of PCPs in the setting of overuse of certain preference sensitive conditions such as antibiotic prescription35 and prostate cancer screening.36 Our study adds to the literature by providing an example encouraging SDM in the context of CRC screening, an effective intervention where SDM might actually increase uptake.7 18 33

The increase in the percentage of PCPs offering FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions after the seminar was primarily due to an intention to increase FIT prescribing and a decrease in those providing only colonoscopy (see online supplementary figure S2). The baseline preference in attendees and non-attendees was for colonoscopy, with about 20% in both groups reporting that colonoscopy was the only screening modality they had prescribed over the past 6 months, supporting evidence that colonoscopy is becoming the leading screening modality in Switzerland.37 There was an increase in PCPs prescribing only colonoscopy among non-attendees, possibly because the screening programme will provide reimbursement without a deductible. Research has shown that despite guidelines advocating a choice of CRC screening methods,1 physicians tend to offer only one screening modality, which is most often colonoscopy.10 Unfortunately, failure to offer a choice might decrease screening rates.7

While we saw an increase in the number of PCPs intending to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions, there was no change in the reported decision-making style. PCPs generally have a positive overall view of SDM, but do not find it appropriate to integrate all elements into every preference-sensitive decision.38 A previous randomised trial of a SDM training programme found that PCP reported decision-making style did not change, but patients reported greater involvement in decision-making and were less likely to receive antibiotics for respiratory tract infections.30 Another trial that led to a change in PCP behaviours related to prostate cancer screening without any change specific metrics of SDM.36 It may not be necessary to change a PCP's reported decision-making style in order to make them more likely to offer the choice of FIT and colonoscopy to their patients.

Our seminar was a multifaceted intervention with lectures, interactivity and discussion, and distribution of SDM tools (see online supplementary figure S1) building on literature that the use of learning methods, such as passive lectures, only is insufficient to change physician behaviour.39 Our objectives were located in the three main domains frequently targeted in medical education, specifically knowledge, skills and attitudes.40 Attitude change was considered as especially important, and was targeted using the presentation of variation in prescribing habits within the assembly, a movie with the narrative of a person choosing FIT and role modelling in the video showing a physician during an ideal SDM encounter.41 Future interventions to reinforce physician behaviour could include evidence-based interventions such as reminders, academic detailing and provider feedback.39 42 The increase in the intention-to- prescribe both FIT and colonoscopy could be because PCPs felt more competent in offering a choice of screening modalities. Competence in health promotion and disease prevention is a required skill in several medical competency frameworks;43 44 specific training in SDM, as demonstrated in our programme, could help ensure that physicians perform prevention activities in a way that respects individual patient values and preferences.

Limitations

Our findings are limited by the fact that the attendees were not randomised to attend the training programme. While we compared the screening intentions of PCPs not attending the training seminar, we found differences in the baseline demographics of attendees and non-attendees. Beyond these demographic differences, there might be other important differences between attendees and non-attendees which limit causal inference from our programme. The demographic make-up of the non-attendees is likely more representative of Swiss primary care.45 However, the response rate among non-responders was low, which limits inferences on the larger population of PCPs in the canton. Data from the two groups were also collected in different circumstances; for the intervention group it was before and after a seminar, while for the comparison group, each PCP received the questionnaire through the mail or electronically and we have no information on the time, location, and circumstances when the questionnaires were filled. However, the baseline views and practice patterns of the two groups were similar, suggesting that our seminar may be able to produce similar results with other Swiss PCPs. Moreover, the similarity between the baseline views of training attendees and the lack of change in the views of non-attendees suggest that outside secular trends, such as increased awareness of CRC screening, were less important.

Our outcomes are based on the intention of PCPs to prescribe both screening modalities roughly equally, and do not represent actual physician prescribing practices. Further, we surveyed attendees directly before and after the seminar, and it is unclear whether these intentions will be sustained after the return to routine practice where there are often multiple barriers to SDM.46 However, other studies have shown that even short educational interventions incorporating films and decision tools can significantly alter the behaviour of PCPs.35 Future studies will need to compare practice patterns in a carefully performed randomised controlled trial (RCT), and over a significant follow-up before we can infer a causal effect of the training programme on reducing variation in care. Also, the seminar was performed by a single multidisciplinary team in one state, and this may make it more difficult to implement elsewhere.

Conclusions

An educational intervention focused on SDM in CRC screening appears to have increased the percentage of PCPs intending to prescribe FIT and colonoscopy in equal proportions. This change might decrease variations in care by decreasing the emphasis on physician preferences for one screening modality over another and place the emphasis on patient preferences. Future studies should test the effect of the intervention within a carefully performed RCT with adequate follow-up, and measure the change in practice to determine whether the change in intended use of FIT and colonoscopy are reflected in practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Isabella Locatelli, PhD, for her help with the choice of statistical analyses, and Céline Braconnier for her help with questionnaire preparation and data entry.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Reto Auer at @retoauer

Contributors: KS, JC, J-LB, CN, GD, CD and RA helped give the training seminars. KS, JC and RA designed and tested the questionnaires. KS and RA collected and analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors helped design the training programme. All the authors undertook revisions, contributed intellectually to the development of this paper, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Primary data and unpublished data are available on request from the corresponding author Selby, Kevin kevin.selby@hospvd.ch.

References

- 1.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:627–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Karsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N et al. , European Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines Working Group. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: overview and introduction to the full supplement publication. Endoscopy 2013;45:51–9. 10.1055/s-0032-1325997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman D. Progress and challenges in colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2115–26. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ 2014;348:g2467 10.1136/bmj.g2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S et al. . Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:171 10.7326/M13-1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L et al. . Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2012;366:697–706. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK et al. . Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:575–82. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB et al. . Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:659–69. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ 2012;345:e6572 10.1136/bmj.e6572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McQueen A, Bartholomew LK, Greisinger AJ et al. . Behind closed doors: physician-patient discussions about colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1228–35. 10.1007/s11606-009-1108-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper GS, Koroukian SM. Geographic variation among Medicare beneficiaries in the use of colorectal carcinoma screening procedures. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1544–50. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30902.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wennberg JE. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. BMJ 2002;325:961–4. 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newhouse JP, Garber AM, Graham RP et al. . Variation in health care spending: target decision making, not geography. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;Suppl Variation:VAR63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulliard JL, Ducros C, Levi F. [Organized screening for colorectal cancer: challenges and issues for a Swiss pilot study]. Rev Med Suisse 2012;8:1464–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Physician-patient communication about colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1493–9. 10.1007/s11606-007-0289-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin GA, Trujillo L, Frosch DL. Consequences of not respecting patient preferences for cancer screening: opportunity lost. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:393–4. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong MC, Ching JY, Chan VC et al. . Informed choice vs. No choice in colorectal cancer screening tests: a prospective cohort study in real-life screening practice. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1072–9. 10.1038/ajg.2014.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Département fédéral de l'intérieur. Ordonnance du DFI sur les prestations dans l'assurance obligatoire des soins en cas de maladie: Modification du 10 juin 2013 2013, page 1930, Art. 12e, let. d. https://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/official-compilation/2013/1925.pdf (accessed 9 May 2016).

- 20.Commission cantonale d’éthique de la recherche sur l’être humain. http://cer-vd.ch/soumission/premiers-pas.html (accessed 13 Feb 2016).

- 21.Shaffer VA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. All stories are not alike: a purpose-, content-, and valence-based taxonomy of patient narratives in decision aids. Med Decis Making 2013;33:4–13. 10.1177/0272989X12463266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R et al. . Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1361–7. 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kripalani S, Bengtzen R, Henderson LE et al. . Clinical research in low-literacy populations: using teach-back to assess comprehension of informed consent and privacy information. IRB 2008;30:13–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M et al. . Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified Delphi consensus process. Med Decis Making 2013;34:699–710. 10.1177/0272989X13501721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giguere A, Légaré F, Grad R et al. . Decision boxes for clinicians to support evidence-based practice and shared decision making: the user experience. Implement Sci 2012;7:72 10.1186/1748-5908-7-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1436–43. 10.1093/jnci/djr318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baur C, Prue C. The CDC Clear Communication Index is a new evidence-based tool to prepare and review health information. Health Promot Pract 2014;15:629–37. 10.1177/1524839914538969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, Levy BT, Daly JM et al. . Comparison of patient preferences for fecal immunochemical test or colonoscopy using the analytic hierarchy process. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:175 10.1186/s12913-015-0841-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawley ST, McQueen A, Bartholomew LK et al. . Preferences for colorectal cancer screening tests and screening test use in a large multispecialty primary care practice. Cancer 2012;118:2726–34. 10.1002/cncr.26551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagnon MP, Candas B, Desmartis M et al. . Involving patient in the early stages of health technology assessment (HTA): a study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:273 10.1186/1472-6963-14-273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wennberg J, Mulley A. Reducing unwarranted variation in clinical practice by supporting clinicians and patients in decision making. In: Gigerenzer G, Muir Gray JA, eds. Better doctors, better patients, better decisions: envisioning health care 2020. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2011:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornuz J, Kuenzi B, Krones T. Shared decision making development in Switzerland: room for improvement! Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen 2011;105:296–9. 10.1016/j.zefq.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF et al. . Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD001431 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S et al. . Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;9:CD006732 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Légaré F, Labrecque M, Cauchon M et al. . Training family physicians in shared decision-making to reduce the overuse of antibiotics in acute respiratory infections: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ 2012;184:E726–34. 10.1503/cmaj.120568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkes MS, Day FC, Srinivasan M et al. . Pairing physician education with patient activation to improve shared decisions in prostate cancer screening: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:324–34. 10.1370/afm.1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fedewa SA, Cullati S, Bouchardy C et al. . Colorectal cancer screening in Switzerland: cross-sectional trends (2007–2012) in socioeconomic disparities. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0131205 10.1371/journal.pone.0131205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards A, Elwyn G, Wood F et al. . Shared decision making and risk communication in practice. A qualitative study of GPs’ experiences. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:6–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith WR. Evidence for the effectiveness of techniques to change physician behavior. Chest 2000;118:8S–17S. 10.1378/chest.118.2_suppl.8S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pangaro L, ten Cate O. Frameworks for learner assessment in medicine: AMEE Guide No. 78. Med Teach 2013;35:e1197–210. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.788789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Légaré F, Moumjid-Ferdjaoui N, Drolet R et al. . Core competencies for shared decision making training programs: insights from an international, interdisciplinary working group. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2013;33:267–73. 10.1002/chp.21197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holden DJ, Jonas DE, Porterfield DS et al. . Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:668–76. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, eds. The draft CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework—series IV. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2015:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach 2007;29:648–54. 10.1080/01421590701392903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selby K, Cornuz J, Senn N. Establishment of a Representative Practice-based Research Network (PBRN) for the Monitoring of Primary Care in Switzerland. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:673–5. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:276–84. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011086supp.pdf (254.8KB, pdf)