Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled trials (non-RCTs, NRCTs) is to investigate the effectiveness and related costs of case management (CM) for patients with heart failure (HF) predominantly based in the community in reducing unplanned readmissions and length of stay (LOS).

Setting

CM initiated either while as an inpatient, or on discharge from acute care hospitals, or in the community and then continuing on in the community.

Participants

Adults with a diagnosis of HF and resident in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

Intervention

CM based on nurse coordinated multicomponent care which is applicable to the primary care-based health systems.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcomes of interest were unplanned (re)admissions, LOS and any related cost data. Secondary outcomes were primary healthcare resources.

Results

22 studies were included: 17 RCTs and 5 NRCTs. 17 studies described hospital-initiated CM (n=4794) and 5 described community-initiated CM of HF (n=3832). Hospital-initiated CM reduced readmissions (rate ratio 0.74 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.92), p=0.008) and LOS (mean difference −1.28 days (95% CI −2.04 to −0.52), p=0.001) in favour of CM compared with usual care. 9 trials described cost data of which 6 reported no difference between CM and usual care. There were 4 studies of community-initiated CM versus usual care (2 RCTs and 2 NRCTs) with only the 2 NRCTs showing a reduction in admissions.

Conclusions

Hospital-initiated CM can be successful in reducing unplanned hospital readmissions for HF and length of hospital stay for people with HF. 9 trials described cost data; no clear difference emerged between CM and usual care. There was limited evidence for community-initiated CM which suggested it does not reduce admission.

Keywords: systematic review, meta-analysis, case management, hospital admission

Strengths and limitations of this study.

High-quality systematic review.

Interventions examine nurse-led multicomponent care of patients with heart failure.

Focus on use of resources specific to heart failure.

Community-initiated case management trials were limited in quantity and were mostly of low quality.

Lack of cost data in most trials.

Introduction

Applying current prevalence figures to population estimates suggests that more than 550 000 individuals (more than 308 000 men and slightly fewer than 250 000 women) in the UK are living with heart failure (HF).1 Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF) data supports this: in 2012/2013, just over 480 000 patients were recorded as having HF.2 The average age of patients with HF in general practice in the UK is 77 years.3

Prior to 1990, 60–70% of patients died within 5 years of diagnosis, and admission to hospital with worsening symptoms was a regular and recurrent event.4–6 Effective treatment has improved care, with a relative reduction in hospitalisation in recent years of 30–50%, and smaller but significant decreases in mortality.4–6

More than £6.8 billion was spent on treating all cardiovascular disease within the National Health Service (NHS) in England in 2012/2013 with 63% of these costs coming from within secondary care and 21% within primary care. Within secondary care, non-elective inpatient admittance for cardiovascular disease, that is, emergency admissions, had the greatest expenditure with £1925 million.1

Case management (CM) is the process of planning, coordinating and reviewing the care of an individual. We used the definition cited by the King's Fund in the UK ‘A collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual's and family's comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost-effective outcomes’.7 The NHS has used less-intensive approaches than the traditional US model, for example, through the use of nurses to support older people and those with long-term conditions at home.8 In this review, we have focused on CM based on nurse coordinated multicomponent care of patients which is applicable to the primary care-based health systems such as that in the UK.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis shows that CM is not effective in reducing unplanned hospital admissions for the general older/elderly population.9 However, limited data suggest that CM for patients with HF is promising.10 This current review aimed to (1) identify the evidence of the effectiveness and related costs of CM interventions for patients with HF predominantly based in the community and (2) to better understand the potential success of CM by examining the components of tested interventions.

Methods

Search

Databases and registries

A search strategy was developed using keywords for the electronic databases according to their specific subject headings or searching structure. The search strategy was run from 1985 to 2012 in the OVID databases—MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO on 2 July 2014 (see online supplementary appendix 1). The search strategy was modified to search internet sites such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the King's Fund. A pragmatic update of these searches was conducted on 20 November 2015 using the full search strategy and run in MEDLINE and MEDLINE in process only.

bmjopen-2015-010933supp_Appendix1.pdf (94.3KB, pdf)

Other sources

Once the included papers were determined, both backwards (reference list of paper) and forwards citation searching (via Google Scholar) was performed to identify any other potentially relevant studies. All authors of included studies in the field were contacted with data queries and to identify additional relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and other controlled studies (non-RCTs, NRCTs; controlled trials, controlled before and after studies, analytic cohorts, comparative studies) were included as determined by our eligibility criteria. We were aware from our previous work that not all community-based studies were randomised and felt it was important to be more inclusive in order to understand why CM may work for HF. CM interventions needed to be initiated either while as an inpatient or on discharge from acute care hospitals including the emergency department (ED), or in the community, and then continue on in the community. Only studies including adults with HF in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries were included as the outcomes were more likely to be comparable for synthesis, and relevant to the UK situation.11 Studies were included as long as one of the outcomes of interest was unplanned hospital (re)admissions, ED attendance, length of hospital stay (LOS) as well as related costs of the interventions. Other outcomes of interest were primary healthcare resources, for example, general practitioner visits, visits to other primary care health professionals or services and prescriptions. Studies written in any language were considered if there was an English abstract available.

Reference management and study selection

EndNote and Excel were used to manage the references. Duplicates were removed from the EndNote file. References underwent a two-stage process of screening using the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers independently (ALH, AK, RJ). First, a screen of titles and abstracts (if abstract available) and second screening of the full paper was conducted. Where there was continued disagreement between reviewers about including or excluding a paper, a third reviewer made the final decision (SP or RJ).

In addition to the included quantitative intervention papers, we identified relevant reviews from the search. Any potentially relevant conference proceedings were followed up, first by searching in MEDLINE to see if the study had been published. If the study was not published, the authors were contacted where possible to check if the studies were likely to be published within the work frame of this review.

Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias

Data were extracted into a custom-designed table which included description of trial type, participants, intervention, controls, outcome measures and results. Based on the Kings Fund definition of CM, we devised taxonomy of intervention components8 (table 1). As part of this data extraction process, the intervention and control treatments were also described by their component parts, for example, monitoring signs and symptoms using the framework of the CM definition.

Table 1.

Components of CM interventions

| Definition and total prevalence of components of CM interventions | Number of hospital-initiated CM vs usual care with component present (total studies=16) | Number of community-initiated CM vs usual care with component present (total studies=4) |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment/evaluation | ||

| Monitoring signs and symptoms (n=18) | ||

| Encompasses general care of patients with CHF which is likely to include establishing a relationship with patient over visits, physical and cardiac status checking, lifestyle assessment, general medication check and screening tests, for example, depression, dementia | 14 | 4 |

| Medication review (n=8) | ||

| Review and adjustment of medication by experienced case manager (nurse), pharmacist, GP or consultant often using a combination of these health professionals | 6 | 2 |

| Assessment of home environment (n=4) | ||

| Assessment carried out by case manager to identify any issues or potential issues with home environment, for example, stairs | 4 | 0 |

| CM meetings/feedback to other HPs (n=5) | ||

| Planning | ||

| Group meetings of health professionals involved in patients with CHF care with the aim of reporting on and planning for patients care | 3 | 2 |

| Appointment organisation (n=2) | ||

| Case manager checking medical appointments, ensuring ability to go, etc | 2 | 0 |

| Advance care planning (n=1) | 1 | |

| Facilitation | ||

| Education/self-management (n=18) | ||

| Educating patients with CHF about their condition, treatment and what to expect. The aim of this is to assist self-management (care with assistance of health professionals) and self-care (patient engaging in activities to promote their health and well-being). | 15 | 3 |

| Patient-directed access (n=6) | ||

| The ability of patients with CHF to initiate care from the case manager or CM service | 6 | 0 |

| Care coordination | ||

| Referral to…(n=14) When the case manager refers the patient to other health or social care professionals, this can be GP hospital consultant, social care or tests. |

11 | 3 |

| Advocacy for options and services | ||

| Equipment (n=4) | ||

| Provision of items to assist patient's healthcare such as pill counters, weighing scales and measured water bottles | 3 | 1 |

| Physical therapy (n=1) | ||

| Patient with CHF receiving physical therapy/rehabilitation | 1 | 0 |

| Support group (n=1) | ||

| CHF attending or being offered the opportunity of a support group. | 1 | 0 |

| Other | ||

| Family involvement (n=9) | ||

| When the case manager involves the patient's family in terms of information, education or involvement, for example, goal setting in patients’ care or active monitoring | 8 | 1 |

| Emotional support (n=1) | ||

| Case manager providing emotional support to patient with CHF. | 0 | 1 |

CHF, chronic heart failure; CM,case management; GP, general practitioner; HP, health professional.

Quantitative data concerning the outcomes of interest were extracted into the Cochrane Revman software. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to record trial bias for RCTs and the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) risk of bias tool was used for NRCTs.12 These processes were performed by one author and checked by a second (ALH, AK). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and if necessary with a third author (RJ, SP).

Data analysis

Trials were divided as previously described by Huntley et al9 into hospital-initiated CM and community-initiated CM. Where there were data from three or more studies, effect sizes were calculated and presented in forest plots as rate ratios ((re)admissions) or mean differences (LOS) using Revman software. If the heterogeneity of the combined data was >50%, a random-effects model was used for analysis.

We conducted prespecified sensitivity analysis in response to the risk of bias assessment of studies, removing high risk of bias studies as appropriate; the results of both analyses are presented.13 We conducted prespecified subgroup analysis to explore the effects of CM duration (3, 6 and 12 months plus) on hospital admission and LOS. There was insufficient detail in trials to perform subanalysis by severity of HF or intensity of intervention.

Data were assessed narratively in respect of the components of interventions using the CM definition cited above as guidance8 (table 1). In addition, where possible, post hoc subgroup analysis was conducted in Revman in which interventions with components of interest were compared with those that did not have these components.

Results

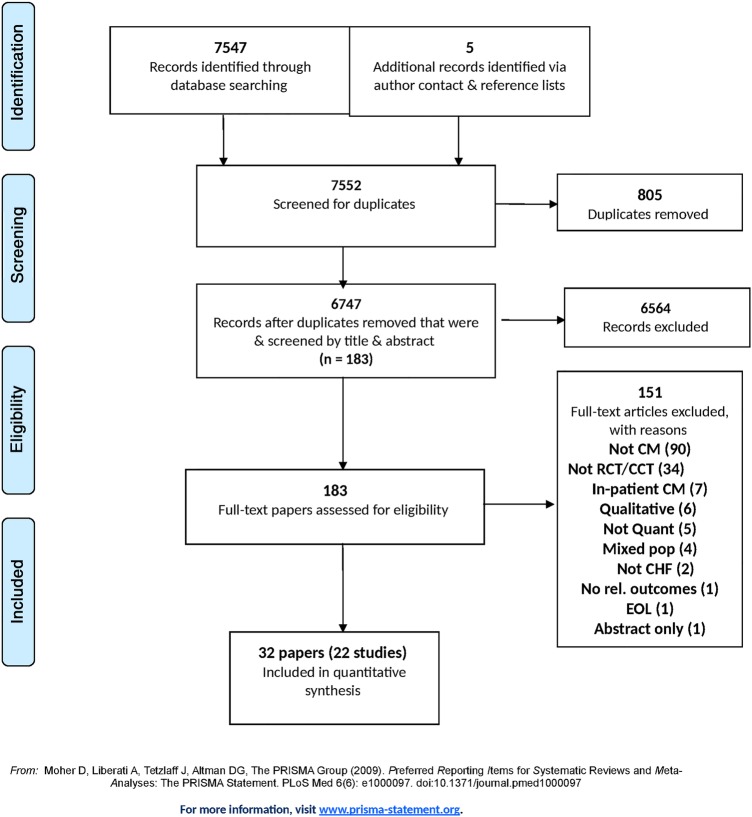

The systematic review yielded 22 studies with data published over 32 papers of which 17 were RCTs and 5 were NRCTs, all published in the English language14–45 (figure 1). No relevant studies were identified in a pragmatic update using the full search strategy run in MEDLINE and MEDLINE in process only in November 2015. Seventeen of these studies described hospital-initiated CM (n=4794),14 15 17 18 20–24 26–28 31 32 and five described community-initiated CM of HF (n=3832).38 42–45 The PRISMA checklist was used to ensure the quality of our systematic review manuscript.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. CCT, controlled clinical trial; CHF, chronic heart failure; CM, case management; EOL, end of life; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Profile of patients

The range of female participants in the trials was 1–58%, but the majority of trials had relatively even gender divide (table 2). Comorbidity and multimorbidity were common. Eight of the 22 trials gave no detail on ethnicity of participants; in four studies, the triallists used white/non-white and English-speaking/non-English-speaking categories. In the remaining 10 studies, a fuller profile was described. Twelve of the 22 trials were conducted in the USA and the ethnicity profile reflected that including Spanish speaking/Hispanic, American Indian, black, African-American, Asian and white participants.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of intervention studies

| Study n=randomised Recruitment/setting |

Baseline characteristics of participants: CM vs usual care | Intervention | Control | Main results Intervention vs control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital-initiated CM—RCTs | ||||

| Rich et al,14 USA n=98 randomised Patients ≥70 years admitted to medical wards of Jewish Hospital at Washington University Medical Centre were screened for congestive HF. |

Age: 80 (6.3), 77.3 (6.1) years p=0.04 Female (%): 60.3, 47.1% Ethnicity: white 46, 57.1% Disease status: Mean NYHA status 2.7 (1.1), 3.0 (1.0) |

Non-pharmacological comprehensive multidisciplinary treatment strategy NPCM (n=63) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Medication review (nurse) Education/self-management support Assessment of home environment Patient-directed access to study personnel |

UC (n=35) Components of intervention: visits by home nurse |

Number of readmissions (%) 21 (CI 21.7% to 44.9%) (33.3%), 16 (29.2% to 62.2%) (45.7%) Total hospital days: 272, 200 Mean number of days: 4.3 (SD1.1), 5.7 (SD2.0) |

| Rich et al,15 USA n=285 randomised As above for Rich et al14 |

Age: 80.1 (5.9), 78.4 (6.1) years p=0.02 Female (%): 68, 59% Ethnicity: non-white race 52, 59% Disease status: Mean NYHA class 2.4 (1.0), 2.4 (1.1) |

Nurse-directed multidisciplinary intervention (n=142) As above for Rich et al14 |

UC (n=140) As above for Rich et al14 |

Number of readmissions 24, 54 p=0.04 Total hospital days 556, 865 Mean number of days 3.9 (10), 6.2 (11.4) p=0.04 |

| Stewart et al,17 Australia n=97 randomised Patients were recruited while admitted to a large tertiary hospital |

Age: 76 (11), 74 (10) years Female (%): 55, 48% Ethnicity: non-English speaking 20.4, 18.75% Disease status: NYHA II 49, 50% III 47, 42% III 4, 4% |

Home-based intervention (n=49) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education (pharmacist)/self-management support Medication review (pharmacist) Referral to GP Family involvement Equipment |

UC (n=48) Components of intervention: DM |

Number of readmissions 36, 63 (p=0.03) Number of patients experiencing a readmission 24, 31 (p=0.12) LOS in days 261, 452 (p=0.05) |

| Stewart et al,18

19 Australia n=200 randomised Patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital |

Age: 75.2 (7.1), 76.1 (9.3) Female (%): 35, 41% Ethnicity: primary language not English 32, 32 Disease status: NYHA II 42, 48 III 46, 43 IV 12, 9 |

Multidisciplinary home base intervention (n=100) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Referral to other health and social care Appointment organisation Assessment of home environment Family involvement Education/self-management support Medication review (nurse/GP/cardiologist) |

UC (n=100) Components of intervention: Contact with other health and social professionals Appointment with GP or cardiac clinic or both |

6 months Number of readmissions 68, 188 (event rates give p=0.02) Rate of readmissions 0.14 (0.1, 018), 0.34 (0.19, 0.49) p=0·031 LOS in days 460, 1174 0.9 (0.6, 1.2), 2.9 (1.9, 3.9) p=0.004 18 months Number of readmissions 64, 125, p=0.02 Mean number of hospital days 10.5 (14.4), 21.1 (24.1) days per patient, p=0.004 |

| Blue et al,20 UK n=165 randomised Patients admitted as an emergency to the acute medical ward of the hospital |

Age: (SD) 74.4 (8.6), 75.6 (7.9) years Female (%): 36, 49% Ethnicity: not reported Disease status: NYHA II 19 (23), 16 (20) III 28 (34), 33 (42) IV 36 (43), 30 (38) Comorbidity or multimorbidity: Angina 40 (49), 38 (45) Past MI 41 (51), 46 (55) Diabetes 15 (19), 15 (18) Chronic lung disease 18 (22), 23 (27) Hypertension 42 (52), 36 (43) AF 42 (52), 29 (35) Valve disease 12 (15), 15 (18) |

Specialist nurse intervention (n=82) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Referral to other health and social care Appointment organisation Medication review (nurse, cardiologist ) |

UC (n=75) Components of intervention: GP care |

Number(%) of readmissions 12 (14), 26 (32) HR 0.38 (0.19, 0.76) p=0.0044 LOS in days 3.43 (12.2), 7.46 (16.6) CI 0.6 (0.41 to 0.88), p=0.0051 |

| Riegel et al,21 USA n=281 physicians randomised Patients admitted at 2 Southern California hospitals |

Age: 72.52 (13.05), 74.63 (12) Female (%): 46.2, 53.9 Ethnicity: (primary language) English 91 (70), 168 (73.7) Spanish 35 (26.9), 58 (25.4) Disease status: NYHA II 2.3, 3.6 III 35.9, 38.4 IV 61.7, 58.0 |

Telephonic CM (n=130) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Self-management support Referral to other HPs (including GP) and social care Family involvement |

UC (n=228) Components of intervention: not known |

Readmission rates 3 months 14.6, 22.8 p=0.06 (calculation 19 people vs 52 experiencing 1 or more admission) 6 months 17.7, 27.6 p=0.06 (calculation 23 people vs 63 people experiencing 1 or more admision) LOS in days 3 months 0.85 (2.3), 1.6 (3.9) p=0.56 6 months 1.1 (3.1), 2.1 (4.6) p=0.05 |

| Laramee et al,22 USA n=287 randomised Patients admitted to hospital for CHF were screened. |

Age: 70.6 (11.4), 70.8 (12.2) years Female (%): 42, 50% Ethnicity: not reported Disease status (SD): NYHA I 10 (7), 35 (26) II 76 (55), 47 (36) III 50 (36), 46 (35) IV 3 (2), 4 (3) Note p<0.001 |

CM (n=131 data available ) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Family involvement Equipment Patient-directed access to CM |

UC (n=125 data available) Components of intervention: not known |

Number of readmissions 3 months period 18 (14) vs21 (17) NS LOS in days in hospital for those patients with ≥1 readmission 6.9 (6.5), 9.5 (9.8) NS |

| DeBusk et al,23 USA n=462 randomised Patients who were admitted with a provisional diagnosis of HF from Kaiser Permanente medical centres in California |

Age: <60 years 15, 14%, 6–70 years 22, 24%, 70–80 years 40, 37%, >80 years 21, 26% Female (%): 52, 45% Ethnicity: American Indian 0, 1% Asian 4, 8% Black 2, 2% White 5, 6% Hispanic 3, 3% Disease status: NHYA I–II 50, 50% III–IV 50, 50% |

CM (n=228) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support CM meetings/feedback to other health providers |

UC (n=234) Components of interventions: not known |

Total number of readmissions in 1 year 76, 86 no stats available |

| Naylor et al,24

25 USA n=239 patients randomised Patients aged 65 years+ admitted to 6 study hospitals from home with a diagnosis of HF were screened for participation. |

Age: 76.4 (6.9), 75.6 (6.5) Female (%): 60, 56% Ethnicity: African-American 34, 38%, white 66, 62% Disease status: Functional status (Moinpur C 1992) Personal 17.1 (5.8), 16.9 (5.8) Social 8.4 (2.6), 8.6 (2.6) Total 25.5 (8), 25.4 (7.8) |

Transitional care intervention with APNs (n=118) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Family involvement CM meetings/feedback to other health providers Patient-directed access to CM |

UC (n=121) Components of intervention: Care from standard home care services Patient-directed access to home care services |

Number of readmissions 40 vears 72 NS $175 840, $498 110 Total hospital days (all cause) 588, 970 Per patient, mean±SD 5.0±7.3 8.0±2.3 NS Per hospitalised patient, mean±SD 11.1±7.2 14.5±13.4 NS |

| Riegel et al,26 San Diego, USA n=135 randomised Self-identified Hispanics were identified at 2 community hospitals close to US-Mexico border. |

Age: 71.6910.8), 72.7 (11.2) Female (%): 58, 49.2% Ethnicity: Hispanic patients Speak/read only Spanish 60.9, 65.1% Disease Status: NYHA II 17.4, 20% III 44.9, 47.7% IV 37.7, 32.3% |

Telephonic CM (n=69) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms self-management support Referral to other HPs (including GP) and social care Family involvement |

Usual care (n=65) Components of intervention: DM information |

Readmission rates (%) (number of people) all NS 1 months 8.7, 13.8% (Calculation 6.003, 8.97) 3-month 21.7, 26.2% (Calculation 14.49, 17.03) 6 months 31.9, 33.8% (Calculation 22.011, 21.97) LOS in days (mean) all NS 1 months 0.59 (2.3), 1.41 (5.5) 3 months 2.19 (5.4), 2.4 (6.2) 6 months 3.65 (7.8), 3.4 (7.1) |

| Thompson et al,27 UK Randomisation was at GP practice level Patients recruited from 2 North of England general hospitals following an admission |

Age: 73 (14), 72 (12) Female (%):38, 27% Ethnicity: no details Disease status: NYHA III and IV 76, 73% |

Clinic and home-based intervention (n=58) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Family involvement In outpatient clinic Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Family involvement Referral to other health and social care |

UC (n=48) Components of intervention at home: unknown |

Number of patients experiencing one or more readmissions 13, 21 Total number of readmissions 15, 45 Total number of hospital days 108, 459 p<0.01 for all at 6 months |

| Jaarsma et al,28

29 The Netherlands n=1049 randomised All patients had been admitted to hospital with symptoms of HF. |

Age: 71 (11), 70 (12), 72 (11) Female (%):34, 39, 40% Ethnicity: no detail Disease status: NYHA II 51, 48, 54% III 47, 48, 42% IV3, 4, 4% |

BNS (n=340) Components of intervention: Outpatients Education/self-management support Patient directed access to HF nurse INS (n=344) Components of intervention at home: Patient-directed access to HF nurse Referral to other health and social care Education/self-management support Equipment |

UC group (n=339) Components of intervention: DM |

Number of readmissions 121,134,120 NS LOS in days (medians) 8.0 (4, 14), 9.5 (5, 17), 12 (5, 19.5) p<0.01 between BNS group and control but NS between INS group and control |

| Brotons et al,31 Spain n=283 randomised Patients were recruited by well-trained nurses at 2 university hospitals. |

Age: 76.6 (7.5), 76 (8.9) years. Female (%): 54.2, 56.1% Ethnicity: not reported Disease status: NHYA I 42.4, 55.4% II 52.1, 37.4% III 4.9, 5.8% IV 0.7, 1.4% |

Home-based intervention (n=144) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Medication review (nurse, physician, cardiologist) Referral to physician or cardiologist as necessary |

UC (n=139) Components of intervention: not known |

Number of readmissions 52, 62 NS Mean number of readmissions 1.01, 1.3 NS |

| Stewart et al,32 WHICH trial, Australia n=280 randomised Patients admitted to participating hospitals were screened for study eligibility. |

Home vs clinic Age: 70 (15), 73 (13) years Female (%):27, 28% Ethnicity: no details Disease status: NYHA II or III 83, 88% Months since CHF diagnosis 34.6 (55.3), 44.8 (71.0) |

Home-based intervention (n=143) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Family involvement CM meetings/feedback to other health providers Referral to other health or social care Assessment of home environment Medication review (nurse, pharmacist, physician, cardiologist) |

Clinic-based intervention (n=137) Components of intervention: In clinic DM Assessment of home environment Family involvement? Referral to other health or social care CM meetings/feedback to other health providers |

Rates of readmissions/100 days/patient 0.52±0.76, 0.53±1.02 NS Mean days of hospitalisation 4.96±8.57, 3.62±6.36 NS At 12–18 months |

| Hospital-Initiated CM—NRCTs | ||||

| Riegel et al,35 USA n=240 were randomised Patients were recruited from 5 hospitals following a hospitalisation for HF. |

Age: 74.44 years. (10.65), 70.77 (11.77) Female (%): 55, 55% Ethnicity: no details Disease status: NYHA I 19.2, 24.2% II 26.7, 18.3% III 43.3, 44.2% IV 10.8, 13.3% |

Multidisciplinary DM (n=120) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Support group Referral to specialist RN visits |

UC (n=120) Components of intervention at home: DM |

Readmission rates 3 months 0.22 (0.52), 0.13 (0.45) (NS) 6 months 0.32 (0.58), 0.23 (0.53) (NS) LOS in days 3 months 0.89 (3.34), 0.48 (1.64) (NS) 6 months 1.31 (3.77), 1.08 (3.46) (NS) |

| Russell et al,36 USA n=447 Patients were referred from a single large not-for-profit general medical and surgical hospital. |

Age: 79.4 (10.7), 79.9 (10.7) Female (%): 55.6, 57.6 (numbers) Ethnicity: White non-Hispanic 56.9, 58.4 African-American 17.0, 16.5 Hispanic 14.8, 14. Asian/other 11.2, 10.7 Disease status: patients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of CHF |

Transitional care service (n=223) Components of intervention at home: Self-management support Referral to other health and social care Assessment of home environment CM meetings/feedback to other health providers Advance care planning Physical therapy |

Usual home care services (n=224) Components of intervention at home: Nurse visits Physical therapy (44.6) Home health aide service (27.7) |

Readmissions Unadjusted OR 30 days 0.58 (0.38, 0.88) p<0.01 Adjusted OR 30 days 0.57 (0.38, 0.87) p<0.01 |

| Stauffer et al,37 USA n=140 Patients were screened for eligibility within 48 h of hospital admission |

Age: 78.9 (8.3), 81.4 (8.3) Female (%): 58.1, 54.8% Ethnicity: Hispanic ethnicity 7.1, 3.6% Disease status: APR-DRG severity of illness 1 5.4, 1.2% 2 44.6, 31% 3 37.5, 57.1% 4 12.5, 10.7% |

Nurse-led transitional care intervention (n=56) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Family involvement Referral (assessing availability of social care) Patient-directed access to study personnel |

Control group (n=84) Components of interventions: unknown |

Readmission rate at 30 days 12.6 (7.4, 17.8) difference −12.6, per cent change −48%; 16.4 (14, 18.7) difference −1.6% change 11% |

| Community-initiated CM—RCTs | ||||

| Peters-Klimm et al,39 Germany n=199 at randomisation Recruitment was via general practice by mail. |

Baseline characteristics of participants: CM, UC Age: 70.4 years (10.0), 68.9 (9.7) Female (%):29, 26% Ethnicity: no details Disease status: NYHA I 1 (1.0), 5 (5) II 63 (64.9), 67 (67) III 33 (34), 27 (27) IV 0, 1 (1.0) Mean years with CHD 6.2 (4.6) (n=79), 6.8 (6.3) (n=74) |

CM (n=97) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Medication review (CM/GP) Referral to GP |

UC (n=100) Components of control intervention: DM Education |

Number of admissions (baseline 36 vs 35) 18 vs 9 at 12 months (NS) Number of patients experiencing one or more CHF admissions 11 vs 7 at 12 months (NS) |

| Wade et al,42 USA n=2200 were randomised Aetna Medicare Advantage members with medical and pharmacy benefits were identified through analysis of claims. |

Age: 75.8, 77.7 years. Female (%): no detail Ethnicity: black/African-American 24, 20.4% Disease status (SD): no detail |

CM (n=152) Components of intervention at home: Referral to other health and social care Equipment |

THCM (n=164) Components of intervention: DM Education Referral to other health and social care |

No data available for primary outcome but described as NS The participant population overall had 42% fewer inpatient days during the intervention period compared with the previous year. No data |

| Hancock et al,43 UK n=28 randomised Residents from 33 of 35 long-term residential and nursing homes |

Age: 85.1 (6.7), 81.8 (7.1) years Female (%):56%, 58% Ethnicity:100% white British Disease status: I:II:III:IV 10:1:4:1, 5:4:1:1 |

CM (n=16) Components of interventions at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education CM meetings/feedback to other health providers Medication review (CM/GP/cardiologist ) |

Routine GP-led care (n=12) Components of intervention: DM |

Number of admissions at 6 and 12 months 0, 0 at 6 months 0, 0 at 12 months |

| Community-initiated CM—NRCTs | ||||

| Bonarek-Hessamfar et al,44 France n=362 Compared patients included prospectively from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2005 from GP list |

Age: median 78, 80 years. Female (%): no details Ethnicity: no details Disease status: NHYA Median of III, IV |

Coordinated care via multidisciplinary network (n=129) Components of intervention at home: Monitoring signs and symptoms Education (diet) Physical therapy CM meetings/feedback to other health provider |

UC ( n=233) Components of intervention: not known |

Number of patients experiencing at least one admission 26, 58 Total number of admissions 35, 96 Median LOS 9.2, 11.7 days In the 2-year period |

| Lowery et al,45 USA n=1043 Intervention implemented in 4 Midwest VA medical centres from the same region and one affiliated outpatient clinic and 2 VA medical centres served as control. |

Age: 65.4 (0.51), 67.4 (0.45) years. Female (%):1, 1% Ethnicity: White 71.2, 79.9% Black 24, 16.1% Other 4.8, 4.0% Disease status: no details |

Nurse-practitioner-led DM model (n=457) Components of intervention at home: Location was lead tertiary centre, other medical centres (some primary care) or one affiliated outpatient clinic. Monitoring signs and symptoms Education/self-management support Referral to other health and social care Family involvement |

UC (n=510) Components of intervention: not known |

Mean number of readmissions 1 year 0.7 (0.32), 0.23 (0.65) p<0.001 (417, 428) 2-year 0.15 (0.58), 0.13 (0.42) NS (384, 382) Mean number of days in hospital 1 year 0.37 (2.25), 0.97 (3.15) p=0.0014 2-year 0.86 (3.98), 0.66 (2.74) NS |

AF, atrial fibrillation; APN, advanced practice nurse; APR-DRG, all-patient refined-diagnosis related group; BNS, basic nurse support; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; CM, case management or case manager; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, disease management; GP, general practitioner; HOCM/RCM, hypertrophic obstructive/restrictive cardiomyopathy; HP, health professional; INS, intensive nurse support; LOS, length of hospital stay; LV, left ventricular; MI, myocardial infarction; NPCM, non-pharmacological comprehensive multi-disciplinary treatment strategy; NRCT, non-randomised controlled trial; NS, not statistically significant; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; SNF, skilled nursing facility; THCM, telehealth with CM; UC, usual care.

The majority of trials described the severity of HF using New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. Twelve of the trials gave a breakdown of numbers or percentages in the I–IV classes with some trials only giving numbers of participants for the III and IV classes. In these trials, the percentage range of III and IV class patients was 6–98%. Four trials gave mean and median values of NYHA status, one trial used the all-patient refined-diagnosis related group (APR-DRG) severity of illness scale, and five trials did not describe disease severity.

Profile of interventions

The majority of studies (n=15) described the intervention being delivered by a case manager/specialist nurse with no specific mention of other health professionals, and the remaining seven studies described a case manager/specialty nurse working as part of a multidisciplinary team (table 2).

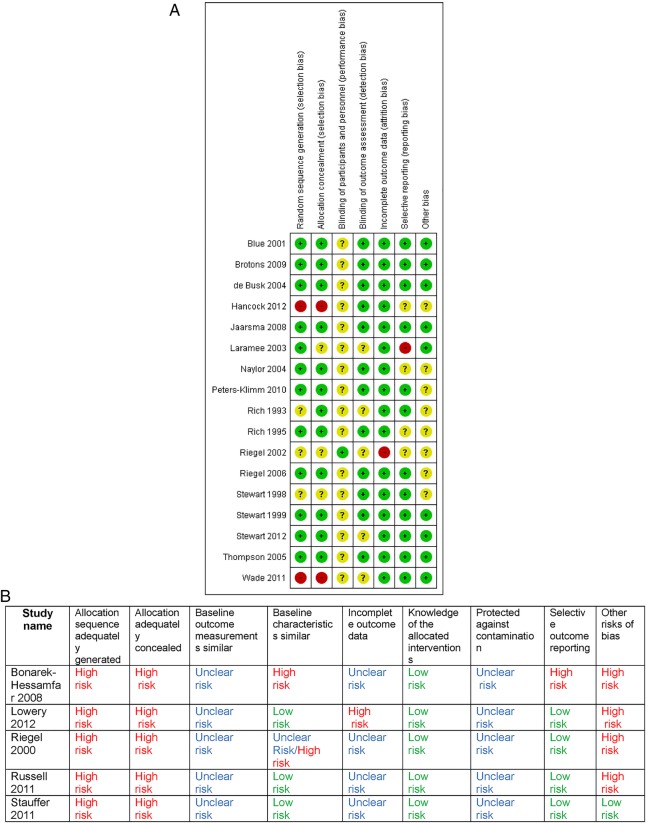

Figure 2.

(A) Risk of bias of included randomised controlled trials. (B) Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) risk of bias for non-randomised controlled trials.

All but two studies compared CM with usual care although the control group was not always described. The two remaining studies were comparative: one RCT comparing CM with specialist clinics and one RCT comparing CM with telemedicine plus CM.32 42

The duration of the CM interventions in the studies was 1–24 months with the majority having a 3-month or 6-month duration. The majority of studies were conducted face to face or a combination of in-person and by phone. Four interventions were conducted purely by phone.21 22 26 42 Outcomes were measured to match the total duration of intervention in the majority of studies. For many of the studies, the intensity of interventions was not stated explicitly. When intensity was described, it was always a tapered approach after an initial intensive period.

Risk of bias

The degree of risk of bias was starkly different between the RCTs and NRCTs. All five of the NRCTs were rated at high risk or unknown risk for most domains (figure 2A, B).35–37 44 45

The majority of the RCTs were rated at low risk for most domains with the exception of the domain of blinding of the participants and personnel which is not applicable to this type of intervention. Three RCTs were assessed as at high risk for at least one domain: both Hancock et al43 and Wade et al42 gave no description of the randomisation process or allocation concealment, Riegel et al21 was randomised at physician level and patients were chosen by physician preference. Four of the five community-initiated trials (two RCTs and two NRCTs) were assessed to be at high risk of bias, and in some studies did not present usable data.35–37 42

All the intervention studies reported unplanned hospital (re)admissions14–45 and 17 reported length of time in hospital.14 15 17 18 20–22 24 26–28 35 38 42–45 There were few data on A and E attendance and primary care resource use. However, only some of the data could be used in meta-analysis with the main reasons being that data were presented in different formats where neither CIs, SEs nor raw data were given. Owing to heterogeneity of data, all analyses were conducted using a random-effects model.

Unplanned HF (re)admissions data

Hospital-initiated CM

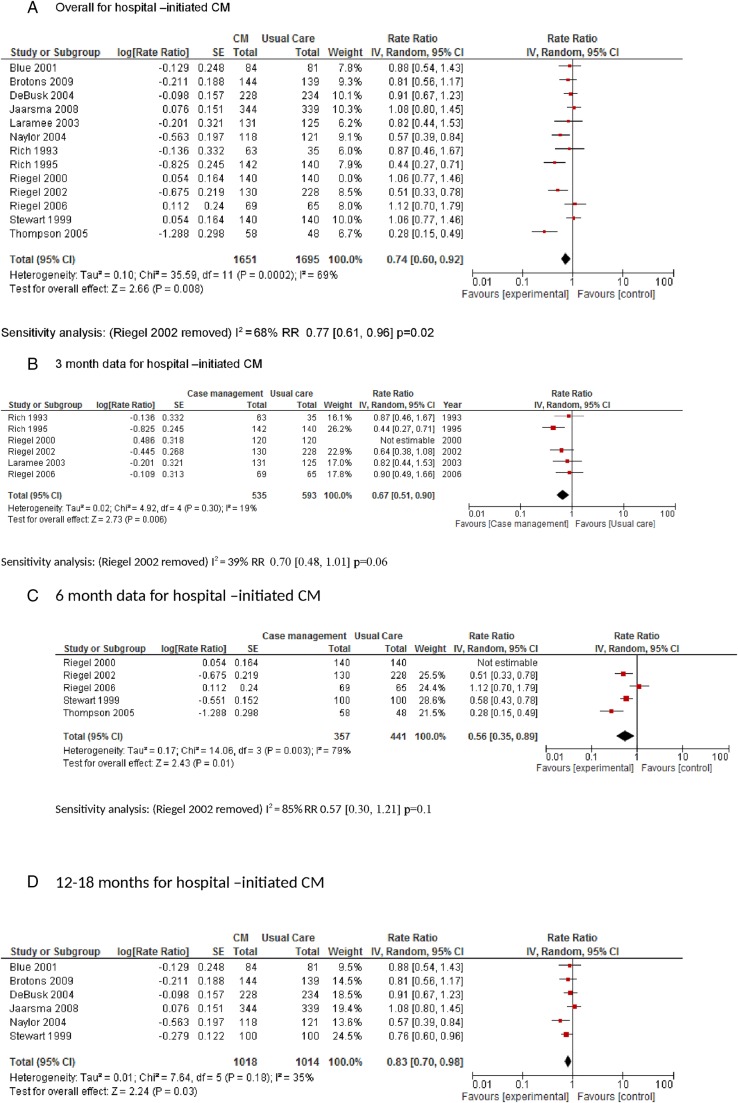

Thirteen of the hospital-initiated CM trials had data that could be used in a meta-analysis of which 12 were RCTs. The pooled data from the RCTs showed a rate ratio of readmissions of 0.74 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.92; p=0.008; I2=69%) in favour of hospital-initiated CM (figure 3A). A sensitivity analysis was conducted, removing Riegel et al21 (RCT with high risk of bias for randomisation domain); this had a minimal effect on the rate ratio and heterogeneity (0.77 (0.61 to 0.96); p=0.02; I2=68%).35 Subanalysis looking at 3-month, 6-month and 12–18-month data did not produce a clear time-related effect which is most likely due to heterogeneity within and between studies (figure 3B–D). There was one hospital-initiated CM trial which compared CM with specialist clinics which reported no differences in hospital readmissions between the two groups.32

Figure 3.

Chronic heart failure (CHF) admissions data. CM, case management.

Community-initiated CM

Of the four community-initiated trials (two RCTs and two NRCTs) comparing admissions between CM with usual care, two reported no significant differences38 43 and two reported statistically significant reductions in favour of CM.44 45 One further trial compared CM, with telehealth and CM and reported no differences in admissions but data were not presented.42

Length of hospital stay

Hospital-initiated CM

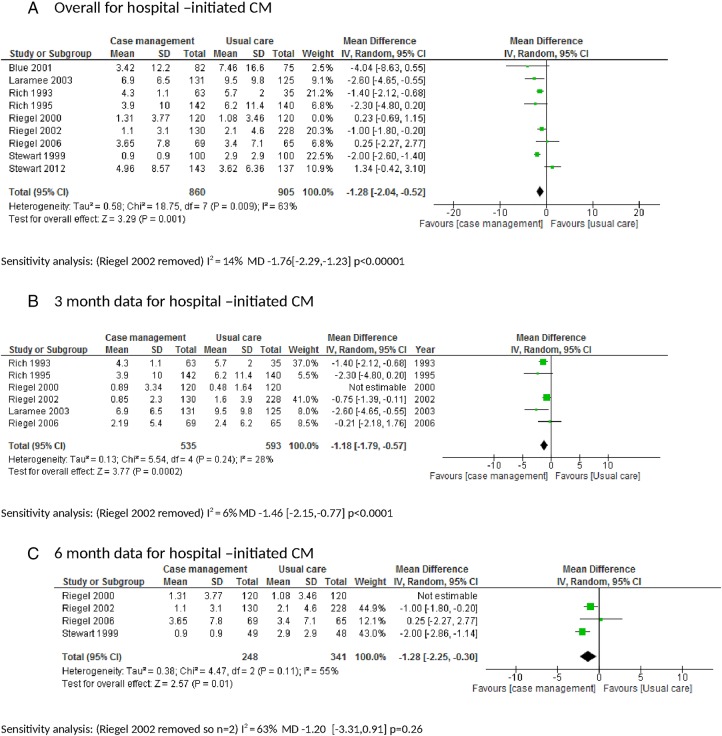

Nine of the hospital-initiated CM trials had data that could be used in a meta-analysis of which eight were RCTs. The pooled data from the RCTs showed that mean LOS was reduced in the CM group compared with usual care mean difference (MD −1.28 days (−2.04 to −0.52); p=0.001; I2=63%; figure 4A). A sensitivity analysis was conducted removing Riegel et al21 which had an important effect on the rate ratio and heterogeneity (MD −1.76 (−2.29 to −1.23); p<0.00001; I2=14%).21 35 Subanalysis looking at 3-month, 6-month and 12–18-month data suggests this effect is short term (first 3 months) but a longer time-related effect was difficult to assess due to lack of data (figure 4B–D).

Figure 4.

Chronic heart failure (CHF) length of hospital stay. CM, case management.

The one study comparing CM with specialist clinic care reported that CM patients accumulated 592 and clinic patients 547 all-cause hospitalisations (p=0.087) associated with 3067 vs 4410 days of hospital stay (p<0.01 for rate and duration of hospital stay).32

Community-initiated CM

Of the four community-initiated trials comparing CM with usual care, two did not report LOS,38 43 one reported median values in favour of CM44 and the remaining one reported a mean reduction in LOS45 (table 2). The one comparative trial between community-initiated CM, and telehealth and CM did not report any useful data.42

Intervention components

Fourteen intervention components were identified and grouped as per the CM definition in methods and prevalence determined for hospital-initiated and community-initiated CM studies with a usual care control group (see tables 1 and 2 and online supplementary appendix 2).7

bmjopen-2015-010933supp_Appendix2.pdf (238.7KB, pdf)

Hospital-initiated CM

Data from individual studies which contained components of family involvement showed an overall reduction in hospital readmissions in comparison with usual care and a reduction in hospital readmissions observationally in comparison with interventions which did not contain these components (rate ratio of 0.56 (0.34 to 0.92); p=0.003). However, post hoc analysis comparing these studies, in which the component was present with those studies in which the component was absent, did not yield any statistically significant differences (p=0.15; see online supplementary appendix 2a). The same calculations for medication review; referral to other services; and assessment of home environment, CM meetings and patient-directed access did not indicate any specific effect of these components of hospital-initiated CM on rates of admission (see online supplementary appendix 2b–g) The majority of the interventions included education/self-management, and there were insufficient data from studies without this component to allow comparison.

Community-initiated CM

There were insufficient data to conduct any subgroup analysis on any of the remaining components of hospital-initiated CM, community-initiated studies or the LOS data.

Outpatient healthcare resources

Only six of the included studies measured outpatient resource use. In some studies, outpatient resource data were all-cause and not HF-specific. In some studies, primary and secondary use was combined.23 24 35 38 42 45 Two of these studies also reported ED attendance.23 42 All but one of these studies reported no difference between intervention and control group for these measures with the exception of Lowery et al45 which showed a statistically significant greater use of outpatient resources in the usual care group (optional primary care visits 1 year 16.75 (13.62); 10.43 (9.6), p<0.001; 2 year 14.27 (11.98); 9.35 (9.97), p<0.001).

Costs

Nine of the 17 hospital-initiated trials described cost data (table 3). Of these, six reported no statistically significant difference between CM (3-month or 6-month duration) and usual care,17 18 22 24 26 35 and three reported costs in favour of CM although data from Stauffer et al37 was brief.15 32 One of these was 12–18 months32 and two were 3 months in duration. It was difficult from the intervention descriptions to determine their intensity. There were no cost data reported from the community-initiated trials.

Table 3.

Available cost data from studies (n=9)

| Study | Cost data intervention vs control (NS=not statistically significant) |

|---|---|

| Rich et al15 | 3-month data Study intervention cost US$216 per person Hospital readmissions $2178 vs $3236 p=0.03 |

| Stewart et al17 | 6-month data Cost of study intervention $A$190 per person Mean cost of hospital-based care $3200 (1800–4600), $5400 (3200–6800) NS Cost of community-based care $620 (460 740), $680 (550 800) NS |

| Stewart et al19 | 6-month and 18-month data 6 months Total hospital-based care $A$490 300 vs $A922 600 NS 18-month data Total hospital-based care $5100 (6800) vs $10 600 (13 000) NS |

| Laramee et al22 | 3-month data Total care costs Mean(US$) 23 054 vs25 536 NS |

| Naylor et al24 | 12-month data CHF readmissions US$175 840 vs US$498 110? Physician's office (outpatients)$4549, $5169 NS ER visits $1780 vs $5650 NS Home visits (all cause) Visiting nurse $11 021, $64 531 p<0.001 APN $104 019 vs 0 Physical therapist $7120 vs $10 918 NS Social worker $178 vs $534 NS Home health aides $9167 vs $11 081 NS Total home visits $138 649 vs $97.883 p<0.001 Total costs $725 903, $1 163 810 NS |

| Stewart et al32 | 12–18-month data Costs per patient $A$1813 (220) vs A$1829 (174) NS Total costs $A$3.93 million vs A$5.53 million p=0.03 for median costs per day |

| Riegel et al35 | 3-month and 6-month data Total costs 3 months US$632 (2378) vs US$317 (1188) NS 6 months $1024 (3017) vs $686 (2225) NS |

| Riegel et al36 | 1-month, 3-month and 6-month data HF inpatient costs all NS 1 month US$1012 (4022) vs US$2830 (13 896) 3-month $3045 (7784) vs $4130 (14 468) 6-month $5567 (13 137) vs $6151 (16 650) |

| Stauffer et al37 | 1-month data ‘Under the current payment system, the intervention reduced the hospital financial contribution on average by US$227for each Medicare patient with HF’ |

APN, advanced practice nurse; CHF, chronic heart failure; ER, emergency room.

Discussion

This systematic review confirms that hospital-initiated CM can be successful in reducing unplanned hospital readmissions, and reducing LOS in hospital in the short term for people with HF. There were only five community-initiated CM studies (three RCTs and two NRCTs) of which four were at high risk of bias. This limited evidence suggests no effect of community-initiated CM on hospital admissions. A minority of trials report cost comparisons with usual care and most of those show no difference. There were limited data on the effect of CM on other healthcare resources.

Many factors are likely to modify the effect of CM on use of emergency care seen in these studies. It is generally accepted that CM is more appropriate for people with severe HF and poorer general health. However, it was difficult to compare the health status of the study participants in hospital-initiated and community-initiated trials as in some studies there was little detail, others gave median and mean figures for NYHA status, and the presentation format and detail of comorbidities varied. All the included studies have been conducted within the past 12 years, so it is important to put these results in the context of overall improved treatment and reduction in hospital admissions since the early 1990s.4–6

Seventeen studies described hospital-initiated CM and five described community-initiated CM of HF, although often the participants were identified via hospital clinic records. Overall, the meta-analysis showed that CM reduced readmissions and hospital LOS. This may be explained by the fact that in most of the trials the participants were identified via hospital contact, and therefore were likely to have had a recent exacerbation of their HF and to be at increased risk of readmission in the postdischarge period. In addition, it is likely that interventions are acting at a time of highest risk as reflected by HF mortality in first year of diagnosis.4 Therefore, once they were assessed and given extra support, they were stable for a period of time. Previous work by Roland et al46 suggests that admission rates in people aged 65 with two or more emergency admissions in 12 months fall in subsequent years without any intervention and account for fewer than 10% of admissions in the following year, and thus effectiveness of admission avoidance schemes cannot be judged by tracking admission rates without careful comparison with a control group. The data from trials of community-initiated CM was lacking both in the number of studies, and the fact there were limited useable data that showed no effect on unplanned hospital admissions. It is likely that these patients were likely to be in more stable health.41

A metareview of a wide range of HF disease management programmes by Savard et al47 reports that nine previous systematic reviews (2001–2009) identified significant reductions in HF admissions with reductions in risk ranging from 30% to 56%. However, the authors caution that these reviews are limited by inadequate reporting in the population, setting, intervention and comparator components. They report that reviewers have not taken into account statistical, clinical and methodological heterogeneity in interventions.47 Our review focused specifically on CM avoiding some of these limitations and indicates a reduction in HF readmissions with hospital-initiated CM in the range of 10–30%.

Wakefield et al48 in 2013 looked at common components of a range of HF care programmes focusing mainly on disease management and education investigated in RCTs, and 10/35 of the discussed studies were included in our review. They described patient education, symptom management by health professionals and by patients, and medication adherence strategies as the most commonly occurring elements of care. A literature review by Jaarsma et al49 looked at 70 ‘home care’ controlled studies (mostly RCTs) which encompassed 9 of our included CM studies covering a wide range of approaches such as telemedicine, hospital at home and health buddies for patients with HF. They identified a multidisciplinary team, continuity of care, care plans, optimising titration of medication, education/counselling of patients and caregivers and increased access as important. Unfortunately, we had insufficient data to perform subanalysis on the component of education/self-management.

Previous systematic reviews have investigated the role of the lay caregiver in HF patient management.50–52 These suggest that better relationship quality and communication were related to reduced mortality, increased health status and less distress, and improved patient self-care outcomes. Our review adds to this evidence base by suggesting that more family involvement in CM may also reduce unscheduled readmissions.

Education about HF and about its pharmacological and non-pharmaceutical treatment has been well reviewed both as an individual approach and as part of complex interventions, and is considered to be essential for improving many patient outcomes.49 53 54 A recent mixed-method study suggests asking patients with HF to write down their learning needs before the education increases their chances of receiving education based on their individual needs.55 Qualitative interviews with health professionals caring for patients with HF suggest that communication with, and education by specialist nurses facilitated by continuity of care is essential to good care of patients with HF. The authors also highlight the role of the specialist nurse in multidisciplinary team communication and functioning, essentially describing the role of the specialist nurse as a case manager.56

Our review of CM suggests that the evidence for its cost-effectiveness is lacking with most studies that have performed cost comparisons with usual care show no advantage. Previous work by de Bruin et al57 looked at cost-effectiveness of disease management for a range of chronic conditions and concluded that the data are most positive for HF with five out of the eight included studies showing cost-effectiveness.

Strengths and limitations

The contribution of our high-quality systematic review to the above is that we have focused on CM which is based on nurse coordinated multicomponent care of patients which is applicable to the primary care-based health systems such as that in the UK. We have focused on HF (re)admissions and LOS as opposed to all-cause data which many of the previous reviews have used.

By examining the components of CM, we have a profile of the components most likely to lead to the success of CM of patients with HF in terms of reducing (re)admissions and hospital LOS. Our review has highlighted the potential importance of family involvement albeit in post hoc analysis.

The limitations of this review are that majority of the community-initiated CM studies were of low quality with the exception of one low risk of bias RCT, and provided limited evidence. While funnel plot analysis was not appropriate with our data, we acknowledge that there may be publication bias on this topic.58 This was counteracted by the fact that the hospital-initiated studies comprised of predominantly community-based CM. There is a lack of cost data and analysis in the included papers. This point needs to be emphasised for future trials. It is possible that cost-effectiveness will be more likely with intervention for patients with more severe HF.

Conclusions

Hospital-initiated CM reduces unplanned hospital admissions, and LOS for people with HF in the short term. Cost data are limited. There was limited evidence for community-initiated CM which suggested it does not reduce hospital admission. Further research is needed to determine the individual components of CM that contribute to reduced admissions.

Footnotes

Contributors: ALH is the main systematic reviewer, and worked across all stages of the review from inception to completed draft. RJ is the cardiology and primary care expertise, and worked on screening, selection of studies, commenting on analysis, and development and checking of final document content. AK is the second reviewer, involved in screening, selection, data checking and commenting on developing and final document content. RWM is the statistical expertise, advising on data analysis and commenting on the developing and final document content. SP is the primary care and admission avoidance expertise, and advised throughout project, third reviewer for screening process and commenting on the developing and final document content.

Funding: This project was funded by the National School of Primary Health Care project no.238.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Full data extraction tables and data analysis files are available on request.

References

- 1.Cardiovascular disease statistics 2014 British Heart Foundation. https://www.bhf.org.uk/~/media/files/publications/research/bhf_cvd-statistics-2014_web_2.pdf on the 7/10/2015.

- 2.Quality and Outcomes Framework Achievement, prevalence and exceptions data 2012/13. 29 October 2013. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB12262/qual-outc-fram-12-13-rep.pdf on the 7/10/2015.

- 3.de Giuli F, Khaw KT, Cowie MR et al. Incidence and outcome of persons with a clinical diagnosis of heart failure in a general practice population of 696,884 in the United Kingdom. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:295–302. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ et al. More ‘malignant’ than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2001;3:315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart S, Ekman I, Ekman T et al. Population impact of heart failure and the most common forms of cancer: a study of 1 162 309 hospital cases in Sweden (1988 to 2004). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:573–80. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhund PS, Macintyre K, Simpson CR et al. Long-term trends in first hospitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation 2009;119:515–23. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross S, Curry N, Goodwin N. Case management. What is it and how it can best be implemented. London, UK: The Kings Fund, 2011. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/case_management.html on the7/10/15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Supporting people with long term conditions. liberating the talents of nurses who care for people with long term conditions. London, UK: Department of Health, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4102469 on 01/12/2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huntley AL, Thomas R, Mann M et al. Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract 2013;30:266–75. 10.1093/fampra/cms081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purdy S. Interventions to reduce unplanned hospital admission: a series of systematic reviews. http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/primaryhealthcare/migrated/documents/unplannedadmissions.pdf on 07/10/2015.

- 11.List of OECD Member countries. http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners/list-oecd-member-countries.htm on 07/10/2015.

- 12.Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_8/8_assessing_risk_of_bias_in_included_studies.htm on 07/10/2015.

- 13.Chapter 9- 9.7 Sensitivity analyses. http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_7_sensitivity_analyses.htmon07/10/2015.

- 14.Rich MW, Vinson JM, Sperry JC et al. Prevention of readmission in elderly patients with congestive heart failure: results of a prospective, randomized pilot study. J Gen Intern Med 1993;8:585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1995;333: 1190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rich MW, Gray DB, Beckham V et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on medication compliance in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Med 1996;101:270–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart S, Pearson S, Luke CG et al. Effects of home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and out-of-hospital deaths. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart S, Marley JE, Horowitz JD. Effects of a multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and survival among patients with chronic congestive heart failure: a randomised controlled study. Lancet 1999;354:1077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart S, Horowitz JD. Home-based intervention in congestive heart failure: long-term implications on readmission and survival. Circulation 2002;105:2861–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ 2001;323:715–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z et al. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure . Arch Intern Med 2002;162:705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laramee AS, Levinsky SK, Sargent J et al. Case management in a heterogeneous congestive heart failure population: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Parker KM et al. Care management for low-risk patients with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL et al. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCauley KM, Bixby MB, Naylor MD. Advanced practice nurse strategies to improve outcomes and reduce cost in elders with heart failure. Dis Manag 2006;9:302–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D et al. Randomized controlled trial of telephone case management in Hispanics of Mexican origin with heart failure. J Card Fail 2006;12:211–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson DR, Roebuck A, Stewart S. Effects of a nurse-led, clinic and home-based intervention on recurrent hospital use in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaarsma T, van der Wal MH, Lesman-Leegte I et al. Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising and Counseling in Heart Failure (COACH) Investigators. Effect of moderate or intensive disease management program on outcome in patients with heart failure: Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising and Counseling in Heart Failure (COACH). Arch Intern Med 2008;168:316–24. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postmus D, Pari AA, Jaarsma T et al. A trial-based economic evaluation of 2 nurse-led disease management programs in heart failure . Am Heart J 2011;162:1096–104. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inglis SC, Pearson S, Treen S et al. Extending the horizon in chronic heart failure: effects of multidisciplinary, home-based intervention relative to usual care. Circulation 2006;114:2466–73. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brotons C, Falces C, Alegre J et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a home based intervention in patients with heart failure: the IC-DOM study. Rev Esp Cardiol 2009;62:400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Marwick TH et al. Impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: the WHICH? (Which Heart Failure Intervention Is Most Cost-Effective & Consumer Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care) multicenter, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1239–48. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Horowitz JD et al. Prolonged impact of home versus clinic based management of chronic heart failure: extended follow-up of a pragmatic, multicentre randomized trial cohort. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:600–10. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Chan YK. Prolonged benefits of nurse-led, home-based intervention versus a specialist heart failure clinic: extended follow-up of the WHICH? Trial Cohort. Eur J Heart Failure 2014;16.. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D et al. Which patients with heart failure respond best to multidisciplinary disease management? J Card Fail 2000;6:290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell D, Rosati RJ, Sobolewski S et al. Implementing a transitional care program for high-risk heart failure patients: findings from a community-based partnership between a certified home healthcare agency and regional hospital. J Healthc Qual 2011;33:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stauffer BD, Fullerton C, Fleming N et al. Effectiveness and cost of a transitional care program for heart failure: a prospective study with concurrent controls. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1238–43. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters-Klimm F, Campbell S, Hermann K et al. Case management for patients with chronic systolic heart failure in primary care: the HICMan exploratory randomised controlled trial. Trials 2010;11:56 10.1186/1745-6215-11-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters-Klimm F, Müller-Tasch T, Schellberg D et al. Rationale, design and conduct of a randomised controlled trial evaluating a primary care-based complex intervention to improve the quality of life of heart failure patients: HICMan (Heidelberg Integrated Case Management). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2007;7:25 10.1186/1471-2261-7-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freund F, Baldauf A, Muth C et al. [Practice-based home visit and telephone monitoring of chronic heart failure patients: rationale, design and practical application of monitoring lists in the HICMan trial]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2011;105:434–45. 10.1016/j.zefq.2010.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters-Klimm F, Campbell S, Müller-Tasch T et al. Primary care-based multifaceted, interdisciplinary medical educational intervention for patients with systolic heart failure: lessons learned from a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2009;10:68 10.1186/1745-6215-10-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wade MJ, Desai AS, Spettell CM et al. Telemonitoring with case management for seniors with heart failure. Am J Manag Care 2011;17:e71–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hancock HC, Close H, Mason JM et al. Feasibility of evidence-based diagnosis and management of heart failure in older people in care: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2012;12:70 10.1186/1471-2318-12-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonarek-Hessamfar M, Benchimol D, Lauribe P et al. Multidisciplinary network in heart failure management in a community based population: results and benefits at 2 years. Int J Cardiol 2009;134:120–2. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowery J, Hopp F, Subramanian U et al. Evaluation of a nurse practitioner disease management model for chronic heart failure: a multi-site implementation study. Congest Heart Fail 2012;18:64–71. 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roland M, Dusheiko M, Gravelle H et al. Follow up of people aged 65 and over with a history of emergency admissions: analysis of routine admission data. BMJ 2005;330:289–92. 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savard LA, Thompson DR, Clark AM. A metareview of evidence on heart failure disease management programs: the challenges of describing and synthesizing evidence on complex interventions. Trials 2011;12:194 10.1186/1745-6215-12-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wakefield BJ, Boren SA, Groves PS et al. Heart failure care management programs: a review of study interventions and meta-analysis of outcomes. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013;28:8–19. 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318239f9e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaarsma T, Brons M, Kraai I et al. Components of heart failure management in home care; a literature review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013;12:230–41. 10.1177/1474515112449539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hooker SA, Grigsby ME, Riegel B et al. The impact of relationship quality on health-related outcomes in heart failure patients and informal family caregivers: an integrative review. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2015;30(Suppl 1):S52–63. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buck HG, Harkness K, Wion R et al. Caregivers’ contributions to heart failure self-care: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2015;14:79–89. 10.1177/1474515113518434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark AM, Spaling M, Harkness K et al. Determinants of effective heart failure self-care: a systematic review of patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions. Heart 2014;100:716–21. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spatola CF, Cocchieri A, De Marinis MG et al. Educational interventions in patients with heart failure: a review of the literature. Ig Sanita Pubbl 2013;69:557–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boyde M, Turner C, Thompson DR et al. Educational interventions for patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011;26:E27–35. 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ee5fb2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ross A, Ohlsson U, Blomberg K et al. Evaluation of an intervention to individualise patient education at a nurse-led heart failure clinic: a mixed-method study. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1594–602. 10.1111/jocn.12760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glogowska M, Simmonds R, McLachlan S et al. Managing patients with heart failure: a qualitative study of multidisciplinary teams with specialist heart failure nurses. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:466–71. 10.1370/afm.1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Bruin SR, Heijink R, Lemmens LC et al. Impact of disease management programs on healthcare expenditures for patients with diabetes, depression, heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review of the literature. Health Policy 2011;101:105–21. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chapter 10 Recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry. http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_10/10_4_3_1_recommendations_on_testing_for_funnel_plot_asymmetry.htm on 07/10/2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010933supp_Appendix1.pdf (94.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010933supp_Appendix2.pdf (238.7KB, pdf)