Abstract

Treatment of severe pain by morphine, the gold-standard opioid and a potent drug in our arsenal of analgesic medications, is limited by the eventual development of hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance. We recently reported that systemic administration of a peroxynitrite (PN) decomposition catalyst (PNDC) or superoxide dismutase mimetic attenuates morphine hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance and reduces PN-mediated mitochondrial nitroxidative stress in the spinal cord. These results suggest the potential involvement of spinal PN signaling in this setting; which was examined in the present study. PN removal with intrathecal delivery of manganese porphyrin-based dual-activity superoxide/PNDCs, MnTE-2-PyP5+ and the more lipophilic MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, blocked hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance in rats. Noteworthy is that intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ prevented nitration and inactivation of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase inactivation enhances the superoxide-to-PN pathway by preventing the dismutation of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide, thus providing an important enzymatic source for PN formation. Additionally, intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ attenuated neuroimmune activation by preventing the activation of nuclear factor kappa B, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen activated protein kinases, and the enhanced levels of proinflammatory cytokines, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6, while increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4 and IL-10. The role of PN was further confirmed using intrathecal or oral delivery of the superoxide-sparing PNDC, SRI-110. These results suggest that mitochondrial-derived PN triggers the activation of several biochemical pathways engaged in the development of neuroinflammation in the spinal cord that are critical to morphine hyperalgesia and tolerance, further supporting the potential of targeting PN as an adjunct to opiates to maintain pain relief.

Keywords: Morphine, Peroxynitrite, Tolerance, Hyperalgesia, Neuroimmune activation, Inflammation, Nitroxidative stress

1. Introduction

Effective morphine analgesia is hindered by adaptive changes such as physical dependence, tolerance, addiction, and well-known side effects [15], as well as by hypersensitivity to noxious and nonnoxious stimuli (ie, hyperalgesia and allodynia) [4]. Understanding the mechanisms that reduce the clinical utility of morphine is relevant for the development of new therapeutic approaches to maintain its effectiveness. We previously reported that peroxynitrite (PN) is essential to morphine antinociceptive tolerance [11,26–28]. PN is formed through the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide [2] and is a potent mediator of nitroxidative stress and inflammation during pain [35]. Once formed, PN reacts irreversibly with many essential biomolecules to induce mitochondrial dysfunction. One such reaction pathway is the selective posttranslational nitration of proteins [41]. We have found that nitration and inactivation of the mitochondrial superoxide regulatory enzyme mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), but not cytosolic copper/zinc SOD (Cu,Zn SOD), occurs in the spinal cord during morphine antinociceptive tolerance and is blocked with systemic PN decomposition catalysts (PNDCs) [26]. PN mediates MnSOD nitration and inactivation, leading to an environment that favors PN formation, which is a feed-forward mechanism we have shown to be critical within the spinal cord during pain [48]. The role of local PN formation in the spinal cord during morphine hyperalgesia and tolerance is unknown. Therefore, in this study, we used spinal administration of PNDCs to reveal the contribution of spinal PN in this setting.

There are numerous mechanisms by which PN formation within the spinal cord can contribute to morphine hyperalgesia and tolerance [36]. Of these, we examined the contribution of PN to neuroimmune activation. Neuroimmune activation is defined as the hyperactivation of glial cells that results in the production of proinflammatory cytokines, reactive nitroxidative species, and other neuroactive substances that contribute to central sensitization during pain, including morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance [32,49]. Key to the development of neuroimmune activation is the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), extracellular- signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38 mitogen activating protein kinases (MAPK) pathways [7,28]. Activation of NF-κB, p38, and ERK can promote inflammation by enhancing the expression of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) proinflammatory cytokines [21,23]. Importantly, PN activates each of these pathways as shown in in vitro studies [22].

We hypothesized that PN is formed within the spinal cord and mediates neuroimmune activation via NF-κB, p38, and ERK activation and enhancing proinflammatory cytokine expression to drive morphine tolerance and hyperalgesia. To this end, we tested whether preventing spinal cord PN accumulation using intrathecal injections of PNDCs that accumulate within mitochondria [34], MnTE-2-PyP5+ and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, blocks hyperalgesia and tolerance as well as NF-κB, p38, and ERK activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression. Because MnTE-2-PyP5+ and MnTn- Hex-2-PyP5+ are nonselective with essentially equal catalytic activities toward both superoxide and PN, the role of PN was supported by intrathecal and oral delivery of a recently characterized superoxide-sparing PNDC, SR110 [33]. Our results are the first to characterize spinal PN as a potent mediator of neuroimmune activation during morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance.

2. Materials and methods

The manganese porphyrin PNDCs, Mn(III) meso-tetrakis (N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin (MnTE-2-PyP5+) andMn(III) mesotetrakis( N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin (MnTnHex-2-PyP5+) were synthesized and characterized as previously described [1] and provided by Dr. Ines Batinić-Haberle, Duke University, North Carolina. Charges of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ are omitted in the figures for simplicity. SRI-110, a neutral Mn(III) complex from the bis-hydroxyphenyldipyrromethene class, was synthesized as described by our group [33].

2.1. Experimental animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (200 to 230 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN, and Italy), housed 3 to 4 per cage, and maintained in a controlled environment (12-hour light/dark cycles) with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines on laboratory animal welfare outlined by the International Association for the Study of Pain and the National Institutes of Health and with regulations in Italy (D.M. 116192), Europe (O.J. of E.C. L 358/1 12/18/1986), and the United States (Animal Welfare Assurance No. A5594-01, Department of Health and Human Services). All animal experiments and care were approved by the St. Louis University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Council directive 87-848, October 19, 1987, Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Forêt, Service Vétérinaire de la Santé et de la Protection Animale, permission 92-256 to S.C.) and the University of Messina Review Board. All experiments were conducted with the experimenters blinded to treatment conditions.

2.2. Osmotic pump implantation

Rats were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and implanted subcutaneously with osmotic minipumps (Alzet 2001; Alza, Mountain View, CA) in the interscapular region. The pumps were filled with saline or morphine and primed according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Each pump was set to deliver (1 μL/h) of saline or morphine (75 μg μL−1 h−1; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) over 7 days as previously described [20]. The concentrations of morphine sulfate resulted in a daily dose of approximately 8 to 9 mg/kg (depending on the weight of the rat). The use of the osmoticpump ensures a continuous subcutaneous delivery of morphine, avoiding intermittent periods of withdrawal. Rats were tested for analgesia at 2 hours after minipump implantation to verify that they were analgesic; approximately 100% analgesia was achieved in all rats tested.

2.3. Drug administration

Each test substance was delivered by intrathecal injection in rats chronically implanted with intrathecal catheters using the lower lumbar approach (ie, L5 and L6 intervertebral space), as described previously [40]. Rats were allowed to recover for 5 days before implanting the osmotic pumps. Administration of test substances began on day 0 after pump implantation and behavioral testing. Test substances were injected intrathecally with a total volume of 10 μL followed by a 10 μL flush with sterile physiological saline. Test substances and vehicle were given once daily for 6 days on day 0 through day 6 after completion of the behavioral tests.

2.4. Behavioral tests

Thermal hyperalgesic responses were measured using the Hargreaves method [16] with an Ugo Basile Plantar Test (Ugo Basile, Comeria, Italy) as previously described [27]. The cutoff latency was 20 seconds to prevent tissue damage. Hindpaw withdrawal latencies (PWL) were taken on day 0 before minipump implantation (baseline) and subsequently on days 1, 3, and 6 of the experimental period. Thermal hyperalgesia was defined as a significant (P < .05) reduction in PWL over time compared with baseline values before osmotic minipump implantation. Baseline PWLs (typically between 14 and 16 seconds) were not significantly different than the subcutaneous infusion of saline (Veh-Sal) PWL (15 ± 0.6) at day 6, thus the Veh-Sal was used for between-group comparisons. Acute nociception was measured using withdrawal latencies of the tail from a noxious radiant heat source (tail-flick test) [9]. The baseline tail flick latencies were set at 2 to 3 seconds and cutoff time at 10 seconds to prevent tissue injury. Antinociceptive tolerance to morphine was indicated by a significant (P < .05) reduction in tail flick latencies after challenge with an acute dose of morphine sulfate (6 mg/kg, given intraperitoneally) at 30 minutes postinjection. Data are expressed as percentage maximal possible antinociceptive effect (%MPE) calculated as follows: (response latency– baseline latency)/(cut off latency–baseline latency) × 100. Thermal hyperalgesia was always measured before the tail-flick test. On day 6 after the behavioral tests, spinal cord tissues from the lower lumbar enlargement (L4–L6) were removed and tissues were processed for Western blot and biochemical analysis.

2.5. Western blot analysis for IκB-α, p38, ERK1/2, and NF-κB

Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described [30]. The levels of nuclear total NF-κB p65 and cytosolic IκB-α, phosphorylated (p)-NF-κB p65, p-p38, and p-ERK1/2 were measured by Western blot. Briefly, protein bands were resolved by 4% to 20% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose. After blocking with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 5% (w/v) nonfat dried milk (PM) for 40 minutes at room temperature, the bands were probed with specific antibodies to IκB-α (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), p-ERK1/2 (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-p38 MAP Kinase (threonine 180/tyrosine 182) (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), p-NF-κB p65 (serine 536) (1:1000; Cell Signaling), or total NF-κB p65 (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 1× PBS, 5% (w/v) nonfat dried milk, 0.1% Tween-20 (PMT) at 4 ºC overnight. The labeled bands were visualized with peroxidase-conjugated bovine antimouse immunoglobulin (Ig) G secondary antibody (1:5000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) or peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1:2000; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and enhanced chemiluminescence. To ensure equal protein loading, the membranes were stripped and reprobed with antibodies against β-actin or lamin (1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The relative expression of the protein bands was measured from scanned films using GS-700 Imaging Densitometer (GS-700, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milan, Italy) and Molecular Analyst (IBM). The dual-phosphorylated form of ERK (pERK) antibody identified 2 bands of approximately 44 and 42 kDa (corresponding to pERK1 and pERK2, respectively).

2.6. Immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting for MnSOD

IP and Western blot analyses were performed as previously described [26,42,48]. Proteins were resolved with 4% to 20% SDS-PAGE before electrophoretic transfer. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at RT in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS-T [1× PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.01% Tween-20], then probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-MnSOD (1:1000; Millipore). Membranes were washed with PBS-T and visualized with peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1:2000; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and enhanced chemiluminescence. In a separate immunoblot, the levels of β-actin were measured to ensure equal protein input for IP using a murine monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:2000), which was visualized with peroxidase-conjugated bovine antimouse IgG secondary antibody (1:5000; Jackson ImmunoResearch). The relative expression of the protein bands was measured from scanned films using a GS-700 Imaging Densitometer (GS-700, Bio-Rad Laboratories) and Molecular Analyst (IBM) and normalized to β-actin bands.

2.7. Measurement of superoxide dismutase activities (cytosolic Cu,Zn SOD and mitochondrial MnSOD) in spinal cord

Spinal cord tissues from the lower lumbar enlargement (L4–L6) were homogenized with 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4), sonicated on ice for 1 minute (20 seconds, 3 times), and centrifuged at 1100g for 10 minutes. The SOD activity in the supernatants was measured by the nitroblue tetrazolium assay as previously described [48] using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 5 Spectrophotometer (Milan, Italy). The Cu,Zn SOD activity was blocked in this assay by the addition of 2 mM NaCN after preincubation for 30 minutes. The amount of protein required to inhibit the rate of NTB reduction by 50% was defined as 1 unit of enzyme activity. Enzymatic activity was expressed in units per milligram of protein [48].

2.8. Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Spinal cord levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-4 were measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The protein expression was normalized to the total protein amount per lumbar spinal cord and reported as pg/mg.

2.9. ED50 determination

The ED50 for the dose-dependent effects of each PNDC on antinociceptive tolerance was determined from a 4-parameter nonlinear curve-fit analysis of the %MPE on day 6 with the Hill slope equal to 1 using GraphPad Prism (release 5.04, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Data are expressed as ED50 (nmol) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

2.10. Statistical analysis of the data

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Time course data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test against day 0 or subcutaneous morphine (Veh-Mor) or by the Dunnett post hoc test against Veh-Mor where noted. The extra sum-of-squares F-test was used to determine whether the %MPE dose-response curves represented distinct curves among treatment groups. Statistically significant differences are defined at a P < .05. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (release 5.04, GraphPad Software Inc).

3. Results

3.1. Intrathecal delivery of MnTE-2-PyP5+ or MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ prevents morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance

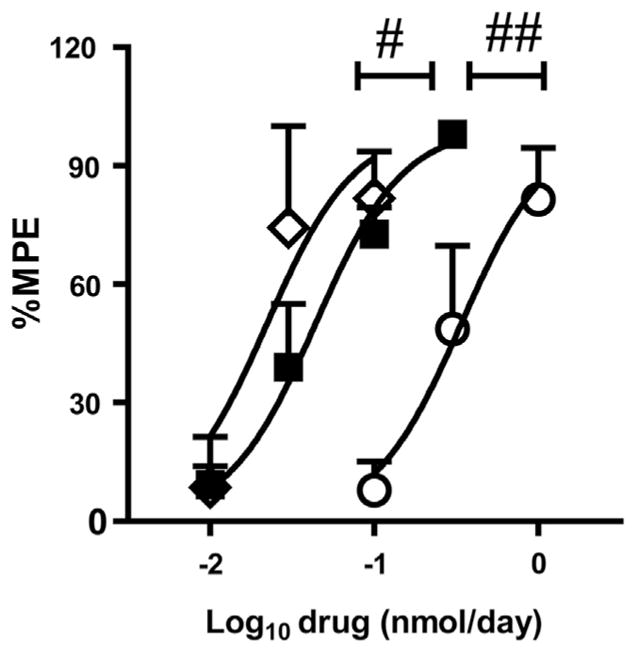

When compared with rats that received 6 days of Veh-Sal (n = 6), rats infused with Veh-Mor (n = 6) became hypersensitive to noxious heat (Fig. 1A, B) and demonstrated a significant reduction in the antinociceptive effects of acute morphine administration (Fig. 1C, D). Thermal hypersensitivity was indicated by significantly decreased PWL. Antinociceptive tolerance was indicated by a significant reduction in percentage maximal possible antinociceptive effect (%MPE) based on tail flick latencies 30 minutes after an acute morphine challenge (intraperitoneally, 6 mg/kg) compared with behavioral responses at baseline (day 0) before osmotic pump implantation. Daily intrathecal delivery of MnTE-2-PyP5+ (0.1 to 1.0 nmol/d, n = 6) and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.01 to 0.1 nmol/d, n = 6) starting on day 0 after pump implantation and behavioral testing prevented morphine-induced hyperalgesia (Fig. 1A, B) and antinociceptive tolerance (Fig. 1C, D), establishing a role for spinal PN. MnTE-2-PyP5+ (1.0 nmol/d, n = 6) and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d, n = 6) in rats receiving subcutaneous saline had no effect on PWL or %MPE. The dose-dependent prevention of antinociceptive tolerance (%MPE, Fig. 2) and subsequent ED50 values (Table 1) on day 6 demonstrated that MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was more potent than MnTE-2-PyP5+ and was used in subsequent mechanistic studies.

Fig. 1.

Intrathecal injections of peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst (PNDCs) prevent morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. When compared with rats that received subcutaneous infusions of saline (Veh-Sal), chronic morphine infusion in rats (Veh-Mor) resulted in significant decreases in hindpaw withdrawal latency (A, B) and percentage maximal possible antinociceptive effect (%MPE) (C, D) on day 6. Daily intrathecal administration of MnTE-2-PyP5+ (0.1 to 1 nmol/d; MnTE-2-PyP-Mor) (A, C) or MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.01 to 0.1 nmol/d; MnTnHex-2-PyP-Mor) (B, D) blocked morphine-induced hyperalgesia and retained %MPE in a dose-dependent manner. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 6 animals. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test. *P < .001 vs Veh -Sal; †P < .001 vs Veh-Mor.

Fig. 2.

Dose-response curves for peroxynitrite decomposition catalysts. Intrathecal SRI-110 (■) and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (◇) were nearly equipotent at reducing antinociceptive tolerance. Both SRI-110 and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ were more potent than MnTE-2-PyP (○). Differences in dose-response curves when compared with SRI-110 were analyzed using the extra sum-of-squares F-test. #P < .05; ##P < .001 vs SRI-110.

Table 1.

ED50 values for peroxynitrite decomposition catalysts.

| Drug | ED50 (nmol/day) | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| MnTE-2-PyP | 0.3 | 0.2–0.5 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP | 0.02 | 0.02–0.03 |

| SRI110 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.06 |

MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and SRI-110 were 15- and 7-fold more potent, respectively, than MnTE-2-PyP5+. The ED50 for the dose-dependent effects of each peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst on antinociceptive tolerance was determined from best-fit curves of the percentage maximal possible antinociceptive effect on day 6 using a 4- parameter nonlinear curve-fit analysis.

3.2. Spinal superoxide-derived PN is required for MnSOD nitration and inactivation

Spinal cord mitochondrial MnSOD had significantly greater levels of nitration (Fig. 3A, B) and decreased activity (Fig. 3C) in rats receiving chronic subcutaneous morphine infusion (n = 5) compared with rats receiving subcutaneous saline (n = 5). Daily intrathecal delivery of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d, n = 5) significantly reduced MnSOD nitration (Fig. 3A, B) and maintained its activity (Fig. 3C) at day 6 compared with vehicle (n = 5). No significant changes were observed in Cu,Zn SOD activity (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Nitration and inactivation of spinal manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) is abrogated by intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+. In subcutaneous morphine infused rats (Veh-Mor), the levels of spinal nitrated MnSOD (A, B) increased as MnSOD activity (C) decreased on day 6 when compared with subcutaneous saline (Veh-Sal). Daily intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d; MnTnHex-2-PyP-Mor) prevented MnSOD nitration (A, B) and inactivation (C). Intrathecal injection of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ had no effect on MnSOD activity in rats receiving subcutaneous saline (MnTnHex-2-PyP-Sal). Spinal copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn SOD) activity was unaltered by any treatment (D). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 5 animals. Composite densitometric analyses for gels of nitrated proteins of 5 rats are expressed as %β-actin (B). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test. *P < .001 vs subcutaneous infusion of saline (Veh-Sal); †P < .01 and ††P < .001 vs Veh-Mor.

3.3. The spinal PN pathway activates NF-κB, ERK, and p38 pathways

When compared with animals receiving daily subcutaneous infusion of vehicle (n = 5), chronic morphine (n = 5) was associated with activation of the NF-κB pathway as evidenced by 1) a significant reduction in total IκB-α, the regulatory protein responsible for sequestering and preventing the activation of NF-κB [21] (Fig. 4A), 2) a significant increase in spinal cord levels of phosphorylated NF-κB p65 in the cytosol (Fig. 4B), and nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 (Fig. 4C). Chronic morphine was also associated with increased MAPK phosphorylation [ERK (Fig. 5A) and p38 (Fig. 5B)] in the spinal cord. Daily intrathecal delivery of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d, n = 5) blocked the phosphorylation (Fig. 4B) and translocation (Fig. 4C) of NF-κB and phosphorylation of ERK (Fig. 5A) and p38 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ blocks nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation. On day 6, when compared with rats that received chronic infusion of vehicle (Veh-Sal), chronic morphine (Veh-Mor) was associated with a significant decrease in spinal cytosolic IκBα (A), and significant increases in levels of spinal cytosolic phosphorylated NF-κB subunit p65 (B) and nuclear p65 (C). These events were abrogated with daily intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d; MnTnHex-2-PyP-Mor) (A-C). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 5 animals. Composite densitometric analyses for gels of proteins of 5 rats are expressed as %β-actin (A, B) or %lamin A/C (C). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test. *P < .01 and **P < .001 vs subcutaneous infusion of saline (Veh-Sal); †P < .001 vs Veh-Mor.

Fig. 5.

The spinal peroxynitrite (PN) pathway is required for activation of mitogen activating protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathways. Chronic morphine (Veh-Mor) was associated with a significant increase in phosphorylation of both extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 subunits 42 and 44 (A) and p38 MAPK (B) compared with rats receiving daily subcutaneous saline (Veh-Sal). Daily intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d; MnTnHex-2-PyP-Mor) (A, B) attenuated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 5 animals. Composite densitometric analyses for gels of proteins of 5 rats are expressed as %β-actin. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test. *P < .001 vs Veh-Sal; †P < .001 vs Veh-Mor.

3.4. Intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ blocks increases in proinflammatory cytokines while enhancing anti-inflammatory cytokines

In agreement with previous reports [26,32], chronic morphine delivery (n = 5) significantly increased the spinal protein expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Fig. 6A), while also increasing, to a lesser degree, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Fig. 6B) on day 6 compared with rats receiving saline (n = 5). There were no effects on IL-4 expression. Daily intrathecal delivery of MnTn- Hex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d, n = 5) with chronic subcutaneous infusion of morphine prevented increases in IL-1β and IL-6 expression (Fig. 6A) while significantly increasing the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 expressions by day 6 (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ decreases proinflammatory and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines. Rats receiving chronic morphine (Veh-Mor) had significantly increased the expressions of the proinflammatory tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 (A) and the anti-inflammatory IL-10 with no change in IL-4 levels (B) compared with subcutaneous infusion of saline (Veh-Sal) on day 6. Intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 nmol/d; MnTnHex-2-PyP-Mor) significantly increased the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10 and IL-4 (B), while preventing the enhanced expression of IL-1β and IL-6 (A). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 6 animals. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test. *P < .05 and **P < .001 vs Veh-Sal; †P < .05 and ††P < .01 vs Veh-Mor.

3.5. Intrathecal SRI-110 prevents morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance

To confirm the contribution of PN to morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance, we used daily intrathecal administration of a superoxide sparing PNDC, SRI-110 [33]. When compared with its vehicle (n = 6), intrathecal SRI-110 (0.03 to 1 nmol/d, n = 6) attenuated morphine-induced thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. 7A) and antinociceptive tolerance (Fig. 7B) in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, intrathecal SRI110 had a potency closer to intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ than MnTE-2-PyP5+ (n = 6; Fig. 2, Table 1) with no differences in efficacies.

Fig. 7.

Spinal SRI-110 attenuates hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. Morphine-induced thermal hypersensitivity (A) and antinociceptive tolerance (B) were blocked in a dose-dependent manner with daily intrathecal administration of SRI-110 (0.03 to 1.0 nmol/d; SRI-110-Mor), compared with intrathecal saline (Veh-Mor) by day 6. SRI-110 (intrathecal 1.0 nmol/d) in rats receiving subcutaneous infusion of saline (SRI-110-Sal) had no effect on paw withdrawal latencies or percentage maximal possible antinociceptive effect (%MPE). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 6 animals. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Dunnett post hoc test *P < .001 vs subcutaneous infusion of saline (Veh-Sal); †P < .001 vs Veh-Mor.

3.6. Oral administration of SRI-110, but not MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, attenuates hyperalgesia and tolerance

Similar to the effects of intrathecal SRI-110, oral administration of SRI-110 (30 mg/kg/d, n = 6) significantly reduced hyperalgesia (Fig. 8A) and tolerance (Fig. 8B). However, oral administration of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (30 mg/kg/d, n = 6) had no effect (Fig. 8A, B). Neither intrathecal (1 nmol/d, n = 6; Fig. 7A, B) nor oral (30 mg/kg/d, n = 6; Fig. 8A, B) delivery of SRI-110 had an effect when administered to rats receiving subcutaneous saline (n = 6).

Fig. 8.

Oral administration of SRI-110 prevents morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. When compared with rats receiving subcutaneous saline (○), chronic morphine (●) resulted in a significant decrease in paw withdrawal latency (PWL) (A) and percentage maximal possible antinociceptive effect (%MPE) (B) by day 6. Daily oral administration of MnTnHex-2-PyP (30 mg/kg/d; ▲) had no effect on the PWL or %MPE; however, SRI-110 (30 mg/kg/d; ■) attenuated the development of hyperalgesia and maintained acute morphine analgesia. Oral administration of SRI-110 in rats receiving subcutaneous saline (□) had no effect on PWL or %MPE. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 6 animals. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post hoc test. *P < .01 and **P < .001 vs t0; †P < .001 vs subcutaneous morphine (Veh-Mor).

4. Discussion

Our findings establish the functional role of PN formed within the spinal cord in the development of morphine hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. PN is formed near the site of superoxide generation, has a half-life of about 10 ms, and can easily diffuse through membranes (between cells or compartments) [41]. Thus, the site of PN formation and site of its activity may not be the same. A primary mitochondrial source of superoxide that can lead to PN formation occurs after the 1 electron reduction of oxygen from enhanced mitochondrial respiration during increased energy demands [41]. Superoxide generation following NADPH oxidase (NOX) activation, such as NOX2 and NOX4, may also occur after morphine-induced activation of Toll-like receptors [29,47,50]. Additionally, we have shown that chronic morphine delivery is associated with activation of ceramide signaling pathways [28], and ceramide signaling can activate NOX in vitro [51]. NOX1 is also implicated in morphine antinociceptive tolerance [17]. The presence of PN within mitochondria is noteworthy because mitochondria are a primary site for the generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, especially during enhanced cellular metabolic stress [41] as found in the spinal cord during inflammatory and neuropathic pain states [35]. This study extends previous findings by demonstrating that mitochondrial nitroxidative stress, specifically nitrated and inactivated MnSOD, depends on the local presence of superoxide-derived PN. PN can cause mitochondrial dysfunction through different mechanisms in addition to MnSOD nitration, which may contribute to hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. For example, PN can suppress mitochondrial respiration, promote apoptosis, and increase reactive oxygen species generation by inactivating electron transport complexes I, II, III, and V; nitrating and inactivating aconitase; nitrating and activating cytochrome c; and inducing opening of the membrane permeability transition pore [41]. Because mitochondrial dysfunction underlies numerous pain states [14,19,39,48], understanding the interactions between PN and mitochondria in the spinal cord is an important focus for future studies.

We observed that PN is required for NF-κB, ERK, and p38 activation as well as enhanced levels of proinflammatory cytokines. PN can activate NF-κB, ERK, and p38 pathways indirectly by inhibiting mitochondrial respiration and through direct redox-sensitive interactions with components of these pathways. For example, inhibition of mitochondrial complexes III and V enhances levels of proinflammatory cytokines, cyclooxygenase II, and prostaglandins through NF-κB activation [3,8,44]; PN inhibits each of these complexes (see earlier). Such mitochondrial dysfunction may also result in enhanced inflammatory cytokine levels and calcium-dependent ERK activation via IL-1 receptor signaling [44,46]. PN directly activates NF-κB through nitration and degradation of IκB-α, inducing the release of NF-κB from IκB-α [22]. Additionally, PN can activate the ceramide signaling pathway [31], which results in NF-κB activation [38]. PN enhances p38 and ERK activation through the oxidation of zinc-sulfur bridges in mitochondria and zinc-thiolate centers in cytosolic enzymes as well as calcium-calmodulin kinase-dependent pathways [22]. Once activated, NF-κB, p38, and ERK can further promote inflammation by enhancing IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α expression [21,23]. Our data support PN-mediated enhancement of proinflammatory cytokines as intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ prevented increased IL-1β and IL-6 levels. Interestingly, intrathecal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ also increased the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10. IL-4 and IL-10 are antinociceptive in pain states [24], and enhanced levels reduce morphine-induced hyperalgesia while maintaining acute morphine antinociception [18]. Removal of PN also significantly enhances spinal IL-4 and IL-10 expression during chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain [12]. The mechanism by which PN regulates IL-4 and IL-10 expression is unknown; however, we have hypothesized that after removal of superoxide and PN, the enhanced expressions of IL-4 and IL-10, which can be nitric oxide– dependent [5,6], may reflect a restoration of nitric oxide levels by shunting it away from the superoxide-PN pathway [12]. Restoring mitochondrial function by PN removal may enhance the effects of anti-inflammatory cytokines because IL-4 actions are partially lost in cells with dysfunction of the electron transport chain [13]. Increased IL-4 and IL-10 may further promote anti-inflammation by reducing the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [10,43], their receptors, subsequent NF-κB activation, and superoxide production [37,45].

By confirming the role of PN using SRI-110, a superoxide-sparing PNDC recently identified by our group [33], these results demonstrate that superoxide’s contribution to pain is predominantly due to its role as a precursor in PN formation. Noteworthy is that SRI-110 and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ were nearly equipotent in the attenuation of hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance on intrathecal administration. As predicted, only SRI-110 was effective when delivered orally. SRI-110 was designed for membrane penetration with a LogP of +4.18, neutral charge, and conformational rigidity [33]. MnTnHex-2-PyP is a pentacationic complex with inherently high hydrophilicity. The 4-hexyl groups appended to the pyridinium substituents were meant to compensate for some of this hydrophilicity. Although MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ still displays a negative LogP of −3.84 (7 orders of magnitude more hydrophilic than SRI-110), the high positive charge of this complex allows electrogenic partitioning into the negatively charged mitochondrial matrix after intrathecal administration [25]. SRI-110 is orally absorbed due to its favorable membrane penetration properties, and these physiochemical characteristics apparently favor partitioning into mitochondria. Both of these disparate molecular design strategies provide effective catalysts, but the SRI-110 design (neutral and membrane soluble) eliminates the detergent-like toxicity of highly charged complexes while enhancing partitioning into compartments in which PN is likely produced. Minimizing perturbations to normal cellular functions while imparting selectivity for PN decomposition renders the SRI-110 catalyst class more attractive for studying the mechanism of PN in morphine hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. Collectively, these data provide additional mechanistic insight for spinal PN signaling while continuing to support our foundational hypothesis that superoxide and PN are key players in pain, including opiate-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from NIH-NIDA (DA024074).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Stevens RD, Hambright P, Fridovich I. Manganese(III) meso tetrakis orthoN-alkylpyridylporphyrins. Synthesis, characterization and catalysis of O2 dismutation. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2002;30:2689–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1620–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco FJ, Rego I, Ruiz-Romero C. The role of mitochondria in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:161–9. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang G, Chen L, Mao J. Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang RH, Feng MH, Liu WH, Lai MZ. Nitric oxide increased interleukin-4 expression in T lymphocytes. Immunology. 1997;90:364–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1997.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Boettger MK, Reif A, Schmitt A, Uceyler N, Sommer C. Nitric oxide synthase modulates CFA-induced thermal hyperalgesia through cytokine regulation in mice. Mol Pain. 2010;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Geis C, Sommer C. Activation of TRPV1 contributes to morphine tolerance: involvement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5836–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4170-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cillero-Pastor B, Carames B, Lires-Dean M, Vaamonde-Garcia C, Blanco FJ, Lopez-Armada MJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction activates cyclooxygenase 2 expression in cultured normal human chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2409–19. doi: 10.1002/art.23644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Amour F. A method for determining loss of pain sensation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1941;72:74–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle T, Bryant L, Muscoli C, Cuzzocrea S, Esposito E, Chen Z, Salvemini D. Spinal NADPH oxidase is a source of superoxide in the development of morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. Neurosci Lett. 2010;483:85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle T, Chen Z, Muscoli C, Bryant L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Dagostino C, Ryerse J, Rausaria S, Kamadulski A, Neumann WL, Salvemini D. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6149–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferger AI, Campanelli L, Reimer V, Muth KN, Merdian I, Ludolph AC, Witting A. Effects of mitochondrial dysfunction on the immunological properties of microglia. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flatters SJ, Bennett GJ. Studies of peripheral sensory nerves in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. PAIN®. 2006;122:245–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foley KM. Misconceptions and controversies regarding the use of opioids in cancer pain. Anticancer Drugs. 1995;6:4–13. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199504003-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. PAIN®. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibi M, Matsuno K, Matsumoto M, Sasaki M, Nakagawa T, Katsuyama M, Iwata K, Zhang J, Kaneko S, Yabe-Nishimura C. Involvement of NOX1/NADPH oxidase in morphine-induced analgesia and tolerance. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18094–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4136-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston IN, Milligan ED, Wieseler-Frank J, Frank MG, Zapata V, Campisi J, Langer S, Martin D, Green P, Fleshner M, Leinwand L, Maier SF, Watkins LR. A role for proinflammatory cytokines and fractalkine in analgesia, tolerance, and subsequent pain facilitation induced by chronic intrathecal morphine. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7353–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph EK, Levine JD. Mitochondrial electron transport in models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain. PAIN®. 2006;121:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King T, Vardanyan A, Majuta L, Melemedjian O, Nagle R, Cress AE, Vanderah TW, Lai J, Porreca F. Morphine treatment accelerates sarcoma-induced bone pain, bone loss, and spontaneous fracture in a murine model of bone cancer. PAIN®. 2007;132:154–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liaudet L, Vassalli G, Pacher P. Role of peroxynitrite in the redox regulation of cell signal transduction pathways. Front Biosci. 2009;14:4809–14. doi: 10.2741/3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. MAPK phosphatases—regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:202–12. doi: 10.1038/nri2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Watkins LR. Glia in pathological pain: a role for fractalkine. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;198:113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miriyala S, Spasojevic I, Tovmasyan A, Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, St Clair D, Batinic-Haberle I. Manganese superoxide dismutase, MnSOD and its mimics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:794–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muscoli C, Cuzzocrea S, Ndengele MM, Mollace V, Porreca F, Fabrizi F, Esposito E, Masini E, Matuschak GM, Salvemini D. Therapeutic manipulation of peroxynitrite attenuates the development of opiate-induced antinociceptive tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3530–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI32420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muscoli C, Doyle T, Dagostino C, Bryant L, Chen Z, Watkins LR, Ryerse J, Bieberich E, Neumman W, Salvemini D. Counter-regulation of opioid analgesia by glial-derived bioactive sphingolipids. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15400–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2391-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ndengele MM, Cuzzocrea S, Masini E, Vinci MC, Esposito E, Muscoli C, Petrusca DN, Mollace V, Mazzon E, Li D, Petrache I, Matuschak GM, Salvemini D. Spinal ceramide modulates the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance via peroxynitrite-mediated nitroxidative stress and neuroimmune activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:64–75. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.146290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HS, Jung HY, Park EY, Kim J, Lee WJ, Bae YS. Cutting edge: direct interaction of TLR4 with NAD(P)H oxidase 4 isozyme is essential for lipopolysaccharide-induced production of reactive oxygen species and activation of NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2004;173:3589–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paterniti I, Mazzon E, Emanuela E, Paola RD, Galuppo M, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S. Modulation of inflammatory response after spinal cord trauma with deferoxamine, an iron chelator. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:694–709. doi: 10.3109/10715761003742993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pautz A, Franzen R, Dorsch S, Boddinghaus B, Briner VA, Pfeilschifter J, Huwiler A. Cross-talk between nitric oxide and superoxide determines ceramide formation and apoptosis in glomerular cells. Kidney Int. 2002;61:790–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raghavendra V, Rutkowski MD, DeLeo JA. The role of spinal neuroimmune activation in morphine tolerance/hyperalgesia in neuropathic and sham-operated rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9980–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09980.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rausaria S, Kamadulski A, Rath NP, Bryant L, Chen Z, Salvemini D, Neumann WL. Manganese(III) complexes of bis(hydroxyphenyl)dipyrromethenes are potent orally active peroxynitrite scavengers. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4200–3. doi: 10.1021/ja110427e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saba H, Batinic-Haberle I, Munusamy S, Mitchell T, Lichti C, Megyesi J, MacMillan-Crow LA. Manganese porphyrin reduces renal injury and mitochondrial damage during ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1571–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salvemini D, Little JW, Doyle T, Neumann WL. Roles of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in pain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:951–66. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvemini D, Neumann WL. Peroxynitrite: a strategic linchpin of opioid analgesic tolerance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawada M, Suzumura A, Hosoya H, Marunouchi T, Nagatsu T. Interleukin-10 inhibits both production of cytokines and expression of cytokine receptors in microglia. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1466–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schutze S, Potthoff K, Machleidt T, Berkovic D, Wiegmann K, Kronke M. TNF activates NF-kappa B by phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C-induced “acidic” sphingomyelin breakdown. Cell. 1992;71:765–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90553-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz ES, Kim HY, Wang J, Lee I, Klann E, Chung JM, Chung K. Persistent pain is dependent on spinal mitochondrial antioxidant levels. J Neurosci. 2009;29:159–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3792-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storkson RV, Kjorsvik A, Tjolsen A, Hole K. Lumbar catheterization of the spinal subarachnoid space in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;65:167–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szabo C, Ischiropoulos H, Radi R. Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2007;6:662–80. doi: 10.1038/nrd2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takagi N, Logan R, Teves L, Wallace MC, Gurd JW. Altered interaction between PSD-95 and the NMDA receptor following transient global ischemia. J Neurochem. 2000;74:169–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.te Velde AA, Huijbens RJ, Heije K, de Vries JE, Figdor CG. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) inhibits secretion of IL-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6 by human monocytes. Blood. 1990;76:1392–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaamonde-Garcia C, Riveiro-Naveira RR, Valcarcel-Ares MN, Hermida-Carballo L, Blanco FJ, Lopez-Armada MJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction increases inflammatory responsiveness to cytokines in normal human chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2927–36. doi: 10.1002/art.34508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Downey GP, Bajenova E, Abreu M, Kapus A, McCulloch CA. Mitochondrial function is a critical determinant of IL-1-induced ERK activation. FASEB J. 2005;19:837–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2657fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Q, Downey GP, Choi C, Kapus A, McCulloch CA. IL-1 induced release of Ca2+ from internal stores is dependent on cell-matrix interactions and regulates ERK activation. FASEB J. 2003;17:1898–900. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0069fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Loram LC, Ramos K, de Jesus AJ, Thomas J, Cheng K, Reddy A, Somogyi AA, Hutchinson MR, Watkins LR, Yin H. Morphine activates neuroinflammation in a manner parallel to endotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200130109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang ZQ, Porreca F, Cuzzocrea S, Galen K, Lightfoot R, Masini E, Muscoli C, Mollace V, Ndengele M, Ischiropoulos H, Salvemini D. A newly identified role for superoxide in inflammatory pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:869–78. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Johnston IN, Maier SF. Glia: novel counter-regulators of opioid analgesia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:661–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang CS, Shin DM, Kim KH, Lee ZW, Lee CH, Park SG, Bae YS, Jo EK. NADPH oxidase 2 interaction with TLR2 is required for efficient innate immune responses to mycobacteria via cathelicidin expression. J Immunol. 2009;182:3696–705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang DX, Zou AP, Li PL. Ceramide-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and endothelial dysfunction in small coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H605–612. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00697.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]