Abstract

The duration of the evolutionary association between a pathogen and vector can be inferred based on the strength of their mutualistic interactions. A well-adapted pathogen is likely to confer some benefit or, at a minimum, exhibit low pathogenicity toward its host vector. Coevolution of the two toward a mutually beneficial association appears to have occurred between the citrus greening disease pathogen, Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (Las), and its insect vector, the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri (Kuwayama). To better understand the dynamics facilitating transmission, we evaluated the effects of Las infection on the fitness of its vector. Diaphorina citri harboring Las were more fecund than their uninfected counterparts; however, their nymphal development rate and adult survival were comparatively reduced. The finite rate of population increase and net reproductive rate were both greater among Las-infected D. citri as compared with uninfected counterparts, indicating that overall population fitness of infected psyllids was improved given the greater number of offspring produced. Previous reports of transovarial transmission, in conjunction with increased fecundity and population growth rates of Las-positive D. citri found in the current investigation, suggest a long evolutionary relationship between pathogen and vector. The survival of Las-infected adult D. citri was lower compared with uninfected D. citri, which suggests that there may be a fitness trade-off in response to Las infection. A beneficial effect of a plant pathogen on vector fitness may indicate that the pathogen developed a relationship with the insect before secondarily moving to plants.

Keywords: Liberibacter, citrus greening, Huanglongbing, fitness

A continuum of interactions, ranging from mutually beneficial to deleterious, may define relationships between prokaryotic plant pathogens and insect vectors (Purcell 1982, Belliure et al. 2005, Stout et al. 2006, Weintraub and Beanland 2006). Coevolution leads to trade-offs between parasite virulence and host traits that may be stable, cyclical, or lead to extinction (Ashby and Boots 2015). Reduced parasite virulence during infection and multiplication within the vector host may result in physiological trade-offs within the vector and subsequent alterations in vector fitness traits, including longevity and reproduction (e.g., Anderson and May 1982). Indirect benefits of pathogens may accrue to their vector host, such as suppression of plant defenses (Belliure et al. 2005) or improvement in the nutritional value of hosts through increased availability of free amino acids (Stout et al. 2006).

The Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liviidae), is the most economically important pest of citrus. D. citri is a phloem-feeding insect that damages developing leaves and fruit. Its primary economic importance lies in its ability to transmit the bacterial pathogen associated with citrus greening disease, or huanglongbing (HLB). HLB occurs throughout citrus-growing regions of Asia, Africa, and the Americas, and is the most significant disease affecting citrus worldwide, resulting in tree decline, reduced fruit quality, and tree death (da Graça 1991, Halbert and Manjunath 2004). In Asia, North America, and Brazil, HLB is associated with a phloem-limited alphaproteobacterium, ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ (Las) (Bové 2006). The bacterium is closely related to two other putative HLB causal agents, ‘Ca. L. africanus’ and ‘Ca. L. americanus’ (Jagoueix et al. 1994, Hocquellet et al. 1999, Teixeira et al. 2005), and the Zebra chip disease causal agent, ‘Ca. L. solanacearum’ (Liefting et al. 2008, 2009; Hansen et al. 2008). The reproductive host range of D. citri extends to a number of plant species in Rutaceae, and citrus plants are a common host (Halbert and Manjunath 2004).

The pathogen is spread by acquisition of ‘Ca. Liberibacter spp.’ when D. citri feed on the phloem sap of infected plants, followed by inoculation of susceptible trees with the bacteria during subsequent feeding. Inoculation of healthy plants with Las can occur after 30 min of feeding (Huang et al. 1984, Xu et al. 1988, Roistacher 1991, Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). The bacteria remain latent inside the vector from 3–20 d and can then be transmitted to new plants within an hour of feeding (Xu et al. 1988, Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). The bacteria presumably multiply within the vector (Moll and Martin 1973, Xu et al. 1988, Ammar et al. 2011).

Transmission of Las by D. citri has been investigated in some detail (Inoue et al. 2009, Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010, Mann et al. 2011); however, the nature of the interaction between this pathogen and its vector remains poorly understood. To date there have been few reports of the effect of Las on psyllid life history. Generally, the impact of pathogens is assessed as a function of their effect on vector survival and fecundity (Weintraub and Beanland 2006). Long life spans may impact vector capacity, by altering the lifetime transmission potential of the vector (Cook et al. 2008). Long life spans facilitate more pathogen transmission, while shorter life spans diminish the opportunity for transmission to occur. The effects of a pathogen on other vector life history traits, such as fertility and fecundity, may also influence disease epidemiology. The production of more offspring in response to pathogen infection can positively impact the fitness dynamics of the vector insect population, increasing the potential for pathogen transmission. In the current study, we examined the effects of the citrus pathogen, Ca. L. asiaticus, on the life history of its insect vector, D. citri. Our objective was to determine the influence of Las on the life history characteristics of D. citri. Specifically, we investigated the effect of infection on: 1) adult survival, 2) fecundity, 3) fertility, and 4) nymph development. Our findings indicate that infection with Las has a positive effect on psyllid population growth, which would be expected to facilitate the spread of huanglongbing.

Materials and Methods

Psyllid Cultures

Diaphorina citri used in bioassays were obtained from a culture continuously reared at the University of Florida Citrus Research and Education Center (CREC) (Lake Alfred, FL). The culture was established in 2000 from field populations collected in Polk Co., FL (28.0′ N, 81.9′ W), prior to the discovery of HLB in the state. A Las-negative colony, consisting of thousands of D. citri individuals, was maintained on ‘Pineapple’ [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osb (Rutaceae)] plants in a greenhouse without exposure to insecticides. To confirm that this culture remained free of Las, random subsamples of D. citri and plants were tested monthly using a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay, described below (Li et al. 2006, Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). Las-positive D. citri were collected from a subculture of the Las-negative population reared on Las-infected C. sinensi ‘Pineapple’ plants housed in a secure quarantine facility at the University of Florida CREC. Las-negative psyllids (P1 generation) were transferred to infected plants immediately preceding assays to obtain Las-infected individuals (F1 generation) for bioassays. Both psyllid colonies were maintained at 26 ± 1°C, 60–80% RH, and a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D) h. Monthly sampling of the infected culture conducted simultaneously with the current study indicated that between 30 to 70% of psyllids were infected with Las based on qPCR detection.

Pathogen Source and Host Plants

Las infection in host plants was maintained by graft inoculating healthy ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange C. sinensis plants with Las-infected vegetative plant tissue (budwood) harvested from a commercial citrus grove in Immokalee, FL (Collier Co., USA). Plants were confirmed positive for Las in a qPCR assay and maintained in an insect-proof secure greenhouse facility at the University of Florida CREC under ambient greenhouse conditions (approximately a photoperiod of 14:10 [L:D] h, 25–28°C, and 60–80% RH). C. sinensis ‘Pineapple’ cultivated from seed and confirmed negative for Las infection were used in the experiments described below. Plants were separated from Las-infected plants in a secure greenhouse and maintained under the above conditions.

Effect of Las on Psyllid Reproduction

Egg Production

The objective of this experiment was to determine the effect of Las infection on the fecundity of D. citri as compared with their uninfected counterparts. Fecundity was defined as cumulative egg production per female over a 25-d oviposition period. Newly emerged (2–3 d old) adults from Las-positive or Las-negative D. citri cultures were sexed and then transferred as pairs (one male and female) onto a Las-negative citrus plant with new leaf growth to promote oviposition. A 1-liter transparent plastic deli container, perforated to provide ventilation, was inverted and attached with parafilm to 1-liter plastic plant pots (11.5 cm diam, 12 cm h) to confine psyllids from each treatment group on healthy (Las-negative) citrus seedlings. Plants with psyllids were held in an environmental chamber (Percival Scientific, Fontana, WI) at 25 ± 1°C, 50 ± 10% RH, under a photoperiod of 14:10 (L:D) h to reflect typical field conditions. Egg production (fecundity) was determined by counting the total number of eggs laid by each isofemale line for 25 d. Eggs were counted and adults were transferred to new plants at 5-d intervals to promote feeding and oviposition on new flush throughout the experiment. To determine egg deposition per female, leaf flush was removed with a sterile scalpel and the number of eggs were counted using a stereomicroscope. Adult females (P1 generation) were collected at the end of the experiment and stored at −80°C in 80% ethanol for subsequent detection of Las. The infection status of P1 females was confirmed using qPCR. Only eggs from Las-infected females were included in fecundity measurements from the Las-infected treatment group for comparison with their Las-negative counterparts.

Egg Fertility

Fertility was defined as the percentage of eggs that successfully hatched following oviposition. Viability of eggs from Las-infected and uninfected females was determined by placing individual excised leaf flush with eggs into 90-mm petri dishes containing 1.5% agar overlaid with moistened filter paper to prevent egg desiccation. Dishes were maintained in an insect-proof growth chamber. Successful egg hatches were determined by counting and removing emerging nymphs daily until no nymphs appeared for one week. Nymphs (F1 offspring) collected throughout the experiment were stored at −80°C in 80% ethanol for subsequent Las screening. The entire experiment was replicated three times on different dates, with 10 replicate female psyllids per treatment for each experiment.

Survival of Psyllids Harboring Las

Fifteen groups of 20 newly emerged (2–3 d old) adult psyllids reared on infected citrus plants for nymphal acquisition of Las were transferred to a healthy (Las-negative) citrus plant to evaluate the effect of Las on D. citri survival. Acquisition feeding was conducted with D. ctiri nymphs because this it is the stage where acquisition of Las is most efficient (Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). A second group of newly emerged adult psyllids reared on healthy plants was also transferred to citrus plants as a negative control. Insects were confined on potted citrus plants within small, insect-proof, mesh rearing cages (0.6 by 0.6 by 0.6 m). Psyllids were collected and counted daily until all individuals were dead. Insects were sorted according to sex, and stored in 80% ethanol at −80°C for DNA extraction. For the Las-infected psyllid treatment, only individuals that tested positive for Las in qPCR assays were included in subsequent survival analysis.

Nymph Development

Paired male and female adult psyllids were collected from an unexposed, Las-negative D. citri culture and confined on asymptomatic, Las-positive, or Las-negative citrus plants with new leaf growth for mating. Following egg deposition, adults were removed from the caged plants and the number of eggs was counted and recorded. Egg clutches from 10 paired psyllids were used for each treatment. Every three days, nymphs were counted by instar and newly emerged adults were collected for storage at −80°C in 80% ethanol for subsequent detection of Las. The experiment continued until all psyllids emerged as adults or died.

DNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR Assays

DNA was isolated from D. citri using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol with modifications for isolation of bacterial DNA from arthropods (Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). Individual psyllids were ground in a buffer solution (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using a sterile mortar, then lysed in a hybridization oven (Model 136400, Boekel Scientific, Feasterville, PA) at 56°C overnight.

Plants were tested for the presence of Las before and after exposure to infected psyllids. Midribs were removed from three leaves collected from each plant using a sterile razor blade. Midribs taken from a single plant were pooled, chopped, and subsampled (100 mg) for total DNA isolation. Samples were frozen under liquid nitrogen and subsequently ground with a bead mill (TissueLyzer II, Qiagen) and stainless steel beads. DNA was isolated using a modified DNeasy Plant Kit (Qiagen) protocol, described previously (Li et al. 2006, Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010).

A Las-specific 16 S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) probe (5′-56FAM-AGACGGGTGAGTAACGCG-3BHQ2-3′) and primers (LasF: 5′-TCGAGCGCGTATGCGAATAC-3′; LasR: 5′-GCGTTATCCCGTAGAAAAAGGTAG-3′) were used in quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays to detect Las (Li et al. 2006). In addition to target DNA, internal control primers were used in multiplex qPCR amplification of samples, as described previously (Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). Each reaction tube contained a primer and probe set to amplify the psyllid wingless gene (Wg) [(WgF: 5′-GCTCTCAAAGATCGGTTTGACGG-3′; WgR: 5′-GCTGCCACGAACGTTACCTTC-3′), Wg probe (5′-JOE-TTACTGACCATCACTCTGGACGC-3BHQ2-3′)], or the plant mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase gene (Cox) to confirm successful extraction of psyllid and plant DNA, respectively. Quantitative PCR settings consisted of: 1) 2 min at 50°C, 2) 10 min at 95°C, and 3) 40 cycles with 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. Duplicate reactions were conducted for each sample in in an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and each set of amplifications included positive controls for target (Las) and internal control (Wg or Cox) sequences. Amplifications were repeated if internal control or positive control assays failed to yield a product. Samples were considered positive for Las if a product was amplified within the 40 amplification cycles used for reactions.

Life Table Analysis and Population Growth Calculation

Data were analyzed using stage-dependent life tables (Birch 1948, Southwood 1978). Life tables were constructed from cohort eggs born to the same female on the same day, with 10–11 replicate females used for each treatment. The net reproductive rate (R0) was calculated as the number of female progeny produced per female per generation, assuming a 1:1 sex ratio, as per the following equation:

x: time (days)

lx: proportion of females alive at time x, and

mx: age-specific fecundity (average daily number of eggs laid by females per treatment divided by 2 to compensate for the 1:1 sex ratio of progeny).

The intrinsic rates of population increase for Las-infected and uninfected psyllids were calculated as described by Birch (1948) as:

T is the generation time (in days), calculated as:

The finite rate of population increase (λ) representing the number of female produced per female per day, was calculated as:

Survival (s) of psyllids was recorded for each life stage (eggs, first–second-instar nymphs, third-instar nymphs, fourth–fifth-instar nymphs, and adults) to determine cumulative mortality (K-value) of psyllids in response to pathogen infection. This is calculated as:

where k is the negative natural logarithm of survival (s) for each life stage, and K is the sum of all k-values for the entire life cycle. The magnitude of the k-value reflects the risk of mortality for a treatment goup, such that mortality of a group increase as k-values increase.

Statistical Analysis

Survival of Las-infected and uninfected D. citri adults was compared on healthy, Las-negative citrus plants using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (SAS Institute 2013). Survival of insects was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and pairwise comparisons between treatment groups were made using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Nymph development time, fertility, and fecundity rates were compared between groups of Las-infected and uninfected D. citri using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; α = 0.05).

Results

Adult Survival

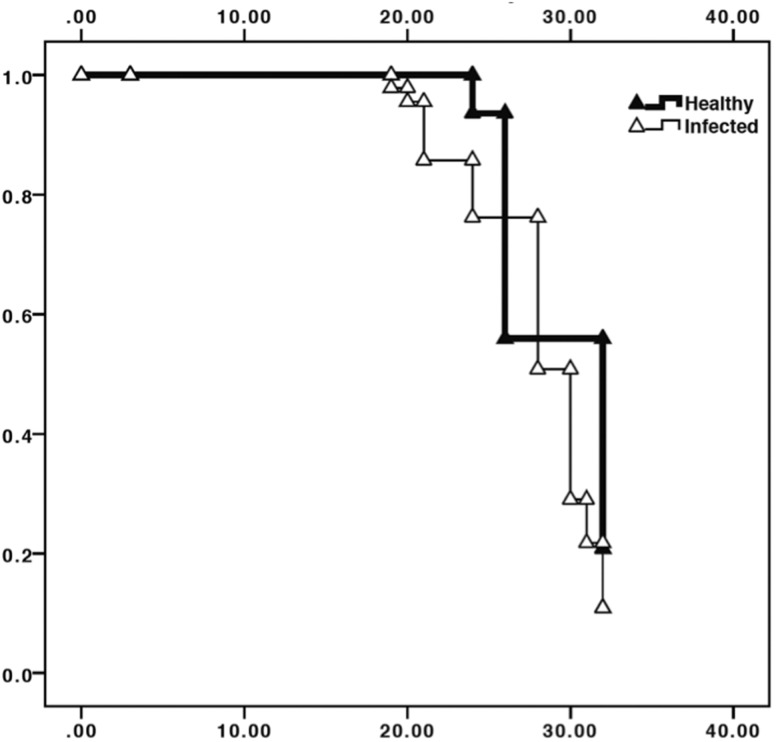

The survival curve of Las-infected D. citri adults was significantly lower than that of uninfected D. citri (Kaplan–Meier analysis, χ2 = 8.31, df = 1, P = 0.004; Fig. 1). Survival of adult D. citri infected with Las at 30 was 18.6 ± 6.7% (mean ± SE) as compared with 34.0 ± 15.0% for infected D. citri.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of cumulative D. citri survival over a 35-d period. Solid triangles represent uninfected D. citri (no exposure to or infection with Las), open triangles represent Las-infected psyllids. Day 0 represents initial emergence of adult psyllids. Survival of Las-infected D. citri adults was significantly lower than that of uninfected D. citri, χ2 = 8.31.

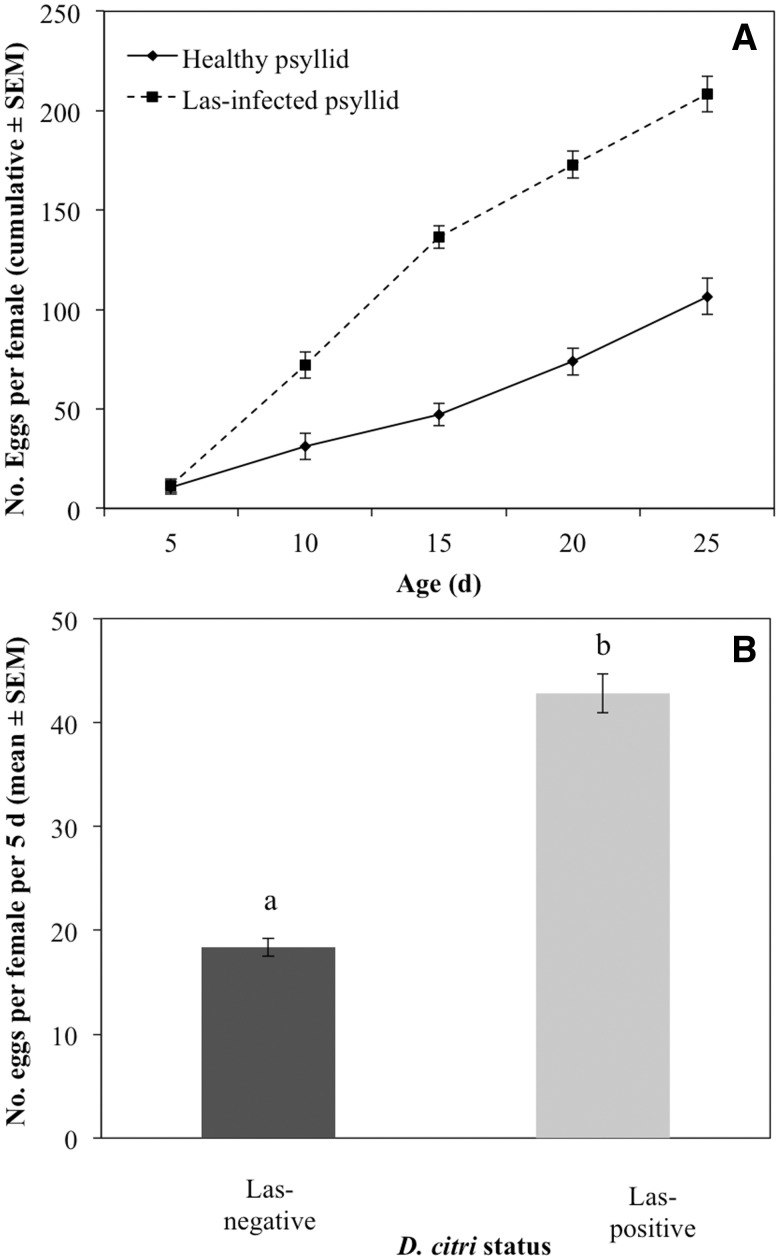

Effect of Las on Reproduction

Fecundity of infected female D. citri was significantly higher than for uninfected counterparts (Fig. 2A). Infected females laid more eggs than uninfected females 10–25 d following acquisition. In addition, the average fecundity of infected females over a 5-d period was significantly higher than the number of eggs laid by noninfected females (Fig. 2B, F1,52 = 100.0, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative (A) and mean (± SEM, n = 15) (B) fecundity of Las-infected or uninfected D. citri. Psyllids were reared on Las-infected or healthy citrus plants, and held on healthy citrus plants for oviposition over 5-d periods. Day 0 represents initial emergence of adult psyllids. Bars labeled with different letters are significantly different from one another (P < 0.05).

Fertility of D. citri was not statistically affected by maternal infection status (F1,19 = 1.23, P = 0.28). The mean percentages of fertile eggs produced by Las-infected and uninfected females were 65.3 ± 5.6 and 74.9 ± 16.8% (mean ± SEM), respectively.

Nymph Survival and Development Period

The developmental time of D citri from egg until adult eclosion was significantly longer on infected (31.2 d ± 0.95 d) than noninfected plants (20.6 ± 0.56 d) (ANOVA, F1,52 = 100.1, P < 0.0001).

Life Table Analysis and Population Growth

Las-positive D. citri experienced greater mortality than Las-negative counterparts at the egg and adult stages; however, less mortality was observed for infected psyllids during the nymphal stage (Table 1). A larger K value, representing cumulative stage-dependent mortality, indicated that Las-infected D. citri experienced greater mortality overall than uninfected psyllids.

Table 1.

Stage-dependent life table of Las-infected and uninfected D. citri

| Psyllid status: | Las-negative |

Las-positive |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Initial N | Survival (s) | ak-value | Initial N | Survival (s) | ak-value |

| Egg | 91.5 | 0.75 | 0.33 | 75.6 | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| Nymph I–III | 613 | 0.23 | 1.53 | 745 | 0.26 | 1.34 |

| Nymph IV–V | 94 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 84 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Adult | 50 | 0.34 | 1.22 | 70 | 0.19 | 1.66 |

| bK | 3.15 | 4.01 | ||||

a k = −ln(s), where s = survival. Larger k values indicate greater psyllid mortality.

b K = Σki, where K represents cumulative k-values for the entire life cycle.

The net reproductive rate of Las-infected D. citri was significantly greater than that of uninfected counterparts (Table 2). Similarly, the finite rate of population increase of infected D. citri was greater than that of uninfected counterparts (Table 2). These results suggest that more adult female D. citri were produced per day by Las-infected, as compared with, uninfected D. citri.

Table 2.

Net reproduction and finite rate of population increase in Las-infected and uninfected D. citri

| Psyllid status | Net reproductive rate (R0) | Finite rate of increase (λ) |

|---|---|---|

| Las-positive | 42.29 | 1.34 |

| Las-negative | 29.97 | 1.24 |

N = 19 (Las-negative) and 18 (Las-positive).

Discussion

The life span of adult D. citri was reduced following acquisition of Las; however, fecundity of infected D. citri was greater as compared with uninfected counterparts. Despite the decrease in psyllid longevity, the net effect on D. citri was positive given that the finite rate of increase was greater when D. citri were infected with Las. This suggests that the positive effect of Las on fecundity of D. citri was greater than the corresponding negative effect on their survival. Acquisition of Las is greatest during nymph development (Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010). Also, transmission of Las by adults may occur mainly when it is initially acquired by nymphs, rather than adults (Ammar et al. 2015). Our findings suggest that D. citri populations may increase more rapidly following acquisition of the Las pathogen than counterpart populations that do not acquire Las during development.

Several leafhopper vectors also exhibit enhanced fitness following acquisition of plant pathogens. Macrosteles quadrilineatus Forbes (Beanland et al. 2000) and Dalbulus maidis (DeLong & Wolcott) (Ebbert and Nault 2001) leafhoppers exposed to the plant pathogens Aster yellows phytoplasma and corn stunt spiroplasma, respectively, live longer than their uninfected counterparts. Positive effects of a plant pathogen on vector fitness may indicate that the pathogen developed a relationship with the insect vector before secondarily moving to plants (Purcell 1982). A close association between Las and its vector has been demonstrated in previous studies reporting the occurrence of transovarial (mother to offspring) (Pelz-Stelinski et al. 2010) and horizontal sexual transmission of Las (Mann et al. 2012). Las is persistently transmitted and capable of colonizing a majority of psyllid tissues, including the reproductive organs (Ammar et al. 2011). Cumulatively, the effects of Las on D. citri suggest a long-term, stable coevolutionary association between these organisms.

Comparable studies have reported detrimental effects of pathogen infection on life history traits of other psyllid species (Malagnini et al. 2010, Nachappa et al. 2012). ‘Candidatuś Phytoplasma mali’ and ‘Candidatuś Liberibacter solenacearum’ are associated with apple proliferation and zebra chip diseases, respectively. These phytopathogens reduce fecundity of their psyllid vectors, Cacopsylla melaneura (Malagnini et al. 2010), and Bactericera cockerelli (Nachappa et al. 2012). Although survival of adult B. cockerelli was not affected by infection, survival of nymphs to the adult stage was reduced when B. cockerelli were infected with Ca. L. solenacearum (Nachappa et al. 2012).

Our results suggest that acquisition of Las may have some negative effects on D. citri given their higher mortality compared with uninfected counterparts. The negative impact on survival may be a direct result of the physiological costs associated with multiplication of the bacteria within D. citri (Ammar 2011). Propagative pathogens can exact metabolic or immune costs associated with multiplication (Nault 1997, Fletcher et al. 1998). Infection with the X-disease, “Flavescence dorée,” and chrysanthemum yellows phytoplasmas reduced the fitness of their respective leafhopper vectors (Jensen 1959; Whitcomb et al. 1967, 1968, 1979; Garcia-Salazar et al. 1991; Bressan 2005; D’Amelio et al. 2008). We postulate that when psyllids are infected with Las, there is a physiological trade-off between reproduction and life span. These trade-offs occur in many organisms, where individuals that reproduce more exhibit shorter life spans (Williams 1966, van Noordwijk and de Jong, 1986, Roff 1992). Few specific physiological mechanisms mediating trade-offs have been described (Partridge 2005, Flatt and Kawecki 2007, Harshman and Zera 2007). Trade-offs are thought to result from competitive resource re-allocation from somatic maintenance and repair to reproduction (Reznick 1985, Bell and Koufopanou 1986, Shanley and Kirkwood 2000, Adler et al. 2013). Hormonal regulation of immune function and metabolic allocation likely underlie life history trade-offs (Flatt and Kawecki 2007, Harshman and Zera 2007).

Mortality of D. citri nymphs was not negatively impacted by acquisition of Las. However, development of D. citri on Las-infected plants was 10.6 d slower than on noninfected plants. As mentioned previously, this may have been due to reduced plant suitability resulting from Las infection. Phloem blockage and collapse are notable features of HLB (Brodersen et al. 2014). Infected plants are nutritionally impacted following Las infection resulting in nitrogen, phosphorus, iron, zinc, and magnesium deficiencies (Mann et al. 2012) and lower amino acid concentrations (da Graça 1991). Although pathogen-infected citrus plants are initially attractive to D. citri, they selectively move to non-infected host plants after feeding (Mann et al. 2012). Adult D. citri will leave Las-infected plants following colonization if uninfected counterparts are nearby (Mann et al. 2012). This is likely because infected plants are nutritionally suboptimal to D. citri as compared with uninfected counterparts (Mann et al. 2012). Therefore, infection of citrus with the Las pathogen may also have negative impact on populations of D. citri because of reduced egg laying on plants by adults as has been shown for the potato psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli (Davis et al. 2012).

Our results may have implications for management of HLB within the context of disease epidemiology. Infected trees may contribute more to spread of the pathogen than by only serving as sources of inoculum for the vector. Increased fecundity of infected D. citri may contribute to transmission because of greater vector population size within heavily infected areas. Given that population growth of the D. citri vector may be greater among populations that harbor the pathogen in greater frequency, as compared with populations that are less infected, our results support previous recommendations for removal of infected host plants as part of HLB management (Bové 2006).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ruben Blanco Perez for his assistance with data collection. This research was supported by the Citrus Research and Development Foundation project #174.

References Cited

- Adler M. I., Cassidy E. J., Fricke C., Bonduriansky R. 2013. The lifespan-reproduction trade-off under dietary restriction is sex-specific and context-dependent. Exp. Gerontol. 48: 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar E., Shatters R. G., Lynch C., Hall D. 2015. Replication of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus in its psyllid vector Diaphorina citri following various acquisition access periods. International Research Conference on Huanglongbing IV. 9-15 February, Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar E., Shatters R. G., Lynch C., Hall D. 2011. Detection and relative titer of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus in the salivary glands and alimentary canal of Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) vector of citrus huanglongbing disease. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 104: 526–533. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.M., May R. M. 1982. Coveolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology 85: 411–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby B., Boots M. 2015. Coevolution of parasite virulence and host mating strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: 13290–13295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beanland L., Hoy C. W., Miller S. A., Nault L. R. 2000. Influence of aster yellows phytoplasma on the fitness of the aster leafhopper (Homoptera: Cicadellidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 93: 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bell G., Koufopanou V. 1986. The cost of reproduction, pp. 83–131. In Dawkins R., Ridley M. (eds.), Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology. Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Belliure B., Janssen A., Mari P. C., Peters D., Sabelis M. W. 2005. Herbivore arthropods benefit from vectoring plant viruses. Ecol. Lett. 8: 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birch L. C. 1948. The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J. Anim. Ecol. 17: 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bové J. 2006. Huanglongbing: A destructive, newly emerging, century-old disease of citrus. J. Plant Pathol. 88: 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bressan A., Girolami V., Boudon-Padieu E. 2005. Reduced fitness of the leafhopper vector Scaphoideus titanus exposed to Flavescence dorée phytoplasma. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 115: 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen C., Narciso C., Reed M., Etxeberria E. 2014. Phloem production in Hunglongbing affected citrus trees. Hort. Sci. 49: 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cook P. E., McMeniman C. J., O’Neill S. J. 2008. Modifying insect population age structure to control vector-borne disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 627: 126–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio R., Palermo S., Marzachi C., Bosco D. 2008. Influence of Chrysanthemum yellows phytoplasma on the fitness of its leafhopper vectors, Macrosteles quadripunctulates and Eudcelidius variegatus. Bull. Insectol. 61: 1721–8861. [Google Scholar]

- da Graça J.V. 1991. Citrus greening disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 29: 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Davis T. S., Horton D. R., Munyaneza J. E, Landolt P. J. 2012. Experimental infection of plants with an herbivore-associated bacterial endosymbiont influences herbivore host selection behavior. PLoS ONE 7: e49330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert M. A., Nault L. R. 2001. Survival in Dalbulus leafhopper vectors improves after exposure to maize stunting pathogens. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 100: 311–324. [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T., Kawecki T. 2007. Juvenile hormone as a regulator of the trade-off between reproduction and life span in Drosphila melanogaster. Evolution 61: 1980–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J., Wayadande A., Melcher U., Ye F. 1998. The phytopathogenic mollicute-insect vector interface: A closer look. Phytopathology 88: 1351–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Salazar C., Whalon M. E., Rahardja U. 1991. Temperature-dependent pathogenicity of the X-disease mycoplasma-like organism to its vector, Paraphlepsius irroratus (Homoptera: Cicadellidae). Environ. Entomol. 20: 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Harshman L. G., Zera A. J. 2007. The cost of reproduction: The devil in the details. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert S. E., Manjunath K. L. 2004. Asian citrus psyllids (Sternorrhyncha: Psyllidae) and greening disease of citrus: A literature review and assessment of risk in Florida. Fla. Entomol. 87: 330–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A. K., Trumble J. T., Stouthamer R., Paine T. D. 2008. A new huanglongbing (HLB) Candidatus species, “C. Liberibacter psyllaurous”, found to infect tomato and potato is vectored by the psyllid Bactericerca cockerelli (Sulc). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74: 5862–5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocquellet A., Toorawa P., Bove J. M., Garnier M. 1999. Detection and identification of the two Candidatus Liberibacter species associated with citrus Huanglongbing by PCR amplification of ribosomal protein genes of the beta operon. Mol. Cell. Probes 13: 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. H., Tsai M. Y., Wang C. L. 1984. Transmission of citrus likubin by a psyllid, Diaphorina citri. J. Agric. Res. China 33: 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H., Ohnishi J., Ito T., Tomimura K., Miyata S., Iwanami T., Ashihara W. 2009. Enhanced proliferation and efficient transmission of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus by adult Diaphorina citri after acquisition feeding in the nymphal stage. Ann. Appl. Biol. 155: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jagoueix S., Bové J. M., Garnier M. 1994. The phloem-limited bacterium of greening disease of citrus is a member of alpha subdivision of Proteobacteria. Intl. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44: 379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen D. D. 1959. A plant virus lethal to its insect vector. Virology 8: 249.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Hartung J. S., Levy L. 2006. Quantitative real-time PCR for detection and identification of Candidatus Liberibacter species associated with huanglongbing. J. Microbiol. Methods 66: 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefting L.W., Ward L. I., Shiller J. B., Clover G.R.G. 2008. A new ‘Candidatus Liberibacter’ species in Solanum betaceum (Tamarillo) and Physalis peruviana (Cape Gooseberry) in New Zealand. Plant Dis. 92: 1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefting L. W., Sutherland P. W., Ward L. I., Paice K. L., Weir B. S., Clover G.R.G. 2009. A new ‘Candidatus Liberibacter’ species associated with diseases of solanaceous crops. Plant Dis. 93: 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagnini V., Pedrazzoli F., Gualandriu V., Forno F., Zasso R., Pozzebon A., Ioriatti C. 2010. A study of the effects of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’ on the psyllid Cacopsylla melanoneura (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103: 65–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R.S., Ali J. G., Hermann S. L., Tiwari S., Pelz-Stelinski K. S., et al. 2012. Induced release of a plant-defense volatile “deceptively” attracts insect vectors to plants infected with a bacterial pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 8: e100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J. N., Martin M. M. 1973. Electron microscope evidence that Citrus Psylla (Trioza erytreae) is a vector of greening disease in South Africa. Phytophylactica 5: 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nachappa P., Shapiro A. A., Tamborindeguy C. 2012. Effect of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum’ on fitness of its insect vector, Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae), on tomato. Phytopathol. 102: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L., Gems D., Withers D. J. 2005. Sex and death: What is the connection?. Cell 120: 461–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelz-Stelinski K. S., Brlansky R. H., Ebert T. A., Rogers M. E. 2010. Transmission of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus by the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. J. Econ. Entomol. 103: 1531–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell A. H. 1982. Insect vector relationships with prokaryotic plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 20: 397–417. [Google Scholar]

- Reznick D. 1985. Costs of reproduction - an evaluation of the empirical evidence. Oikos 44: 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Roff D. A. 1992. The evolution of life histories: Theory and analysis. Chapman & Hall, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Roistacher C. N. 1991. Greening, pp. 35–45. In Techniques for biological detection of specific citrus graft transmissible diseases. FAO, Rome. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. 2013. SAS users guide version 5.1. SAS Institute, Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Shanley D. P., Kirkwood T. B. L. 2000. Calorie restriction and aging: A life-history analysis. Evolution 54: 740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout M. J., Thaler J. S., Thomma B.P. 2006. Plant-mediated interactions between pathogenic microorganisms and herbivorous arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51: 663–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira D. C., Saillard C., Eveillard S., Danet J. L., Costa P. I. da, Ayres A. J., Bové J. M. 2005. ‘Candidatus Liberibacter americanus’, associated with citrus huanglongbing (greening disease) in São Paulo State, Brazil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micrbiol. 55: 1857–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk A., Jong G. de. 1986. Acquisition and allocation of resources: Their influence on variation in life history tactics. Am. Nat. 128: 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub P. G., Beanland L. 2006. Insect vectors of phytoplasmas. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51: 91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb R. F., Williamson D. L. 1979. Pathogenicity of mycoplasmas for arthropods. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Orig. A. 245: 200–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb R. F., Shapiro M., Richardson J. 1966. An Erwinia like bacterium pathogenic to leafhoppers. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 8: 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb R. F., Jensen D. D., Richardson J. 1967. The infection of leafhoppers by Western X-disease virus. III. Salivary, neural, and adipose histopathology. Virology 31: 539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. C. 1966. Natural selection, the costs of reproduction, and a refinement of Lack’s principle. Am. Nat. 100: 687–690. [Google Scholar]

- Xu C. F., Xia Y. H., Li K. B., Ke C. 1988. Further study of the transmission of citrus huanglongbing by a psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, pp. 243–248. In Timmer L. W., Garnsey S. M., Navarro L. (eds.), Proceedings, 10th Conference International Organization Citrus Virology University of California, Riverside, CA. [Google Scholar]