Abstract

The innate immune system provides protection from infection by producing essential effector molecules, such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that possess broad-spectrum activity. This is also the case for bumblebees, Bombus terrestris, when infected by the trypanosome, Crithidia bombi. Furthermore, the expressed mixture of AMPs varies with host genetic background and infecting parasite strain (genotype). Here, we used the fact that clones of C. bombi can be cultivated and kept as strains in medium to test the effect of various combinations of AMPs on the growth rate of the parasite. In particular, we used pairwise combinations and a range of physiological concentrations of three AMPs, namely Abaecin, Defensin and Hymenoptaecin, synthetized from the respective genomic sequences. We found that these AMPs indeed suppress the growth of eight different strains of C. bombi, and that combinations of AMPs were typically more effective than the use of a single AMP alone. Furthermore, the most effective combinations were rarely those consisting of maximum concentrations. In addition, the AMP combination treatments revealed parasite strain specificity, such that strains varied in their sensitivity towards the same mixtures. Hence, variable expression of AMPs could be an alternative strategy to combat highly variable infections.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Evolutionary ecology of arthropod antimicrobial peptides’.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptides, trypanosome, Bombus, synergy, combination

1. Introduction

When parasites infect a host, the so-called innate immune system is the first line of defence, while the adaptive system—based on expanding T- and B-cell populations—is only recruited somewhat later. However, in all invertebrates, including insects, the adaptive system is missing and, hence, defence is entirely ensured by the innate immune system. When challenged, the innate system produces—among other things—an array of effector molecules that are able to damage or kill an invading pathogen. This includes the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) [1].

AMPs are small molecules (up to around 100 amino acids), which are present in a wide array of organisms representing an enormous diversity in structure and morphology. They have broad-spectrum activity against many pathogens (antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal) and are well known for their rapid onset of killing [2]. Peptides have diverse modes of action, including disrupting microbial homeostasis, membrane permeabilization and rupture, inhibition of protein synthesis, or induction of the synthesis of reactive oxygen species causing cell death [3–5]. AMPs are classified based on their molecular structure as well as on the presence of particular amino acid residues [1]. The number of different AMPs present in any one organism varies considerably, with more than 50 in some insects [6], six in the honeybee, Apis mellifera [7], with the recently sequenced bumblebees having only four [8,9].

AMPs should ensure defence against parasites, which are a common, diverse and major threat to any organism [10]. Among the classes of parasites, trypanosomes are of great interest, as they are known to be virulent, for example, in humans and livestock [11,12]. Moreover, trypanosomes are also common pathogens of insects. We here study the common European bumblebee, Bombus terrestris, which is regularly infected by the trypanosomatid gut parasite Crithidia bombi [13]. Under good conditions, infection does not lead to mortality, but under stressful conditions such as starvation, worker mortality rate increases substantially [14]. The major effect results from the near-castration of founding queens in spring [15], such that infected queens have low fitness even if they managed to found a colony.

When a bumblebee host is infected, several pathways of the immune system become activated, which—among other things—leads to the expression of AMPs [16,17]. This includes the proline-rich Abaecin, cysteine-rich Defensin and glycine-rich Hymenoptaecin. Their expression is crucial for controlling this parasite, as their suppression by RNAi leads to higher infection intensities in treated hosts compared with their control counterparts [18]. This fits with earlier findings that AMPs are effective against protozoan parasites, such as Leishmania donovani and Plasmodium [19,20], as well as against African trypanosomes [21].

Because the primary genomic sequence of AMPs eventually determines the structure of the peptide and thus its function, signatures of selection attributed to pressure exerted by the co-evolving parasites are to be expected. However, while AMPs in vertebrates typically show clear signs of selection [22], evidence for adaptive evolution of the genomic sequence of AMPs in insects is only moderate at best and hard to find in many cases [23–26.] On the other hand, gene duplications and deletions occur over short evolutionary time scales at the level of AMP gene families [27,28], and extant AMP polymorphism may be based on allelic variation [29] instead. Signatures of selection are evident for components of the signalling pathways where the respective genes evolve rapidly at the amino acid sequence level [27,30,31]. This general situation also applies to bumblebees, where AMPs are highly conserved ([9,32]; Ben Sadd 2010, unpublished data). This observation is puzzling, since the question arises as to how such small and conservative molecules are able to remain effective over evolutionary time, despite the pressure by parasites that is expected to drive a co-evolutionary arms race.

As several AMPs are expressed and induced by an infection, selection for efficiency of expression and for the combination of particular AMPs, in contrast to selection on the genomic sequence itself, may therefore be crucial for the host to keep up in this race. Hence, the expressed mixture of AMPs could be synergistically more effective than the averaged efficacy of single peptides. Such synergistic effects have been suspected for some time and are indeed known for AMPs, often in combination with ‘non-natural’ partners, such as administered antibiotics or other added molecules [33–42]. For the bumblebee AMPs, Hymenoptaecin has been shown to make the membrane of E. coli permeable, such that Abaecin can enter the cell, where it interacts with the chaperone DnaK. Hence, there is a mechanistic basis for a synergistic effect of these two AMPs; at the same time, no efficacy against bacteria is found for Abaecin alone [43]. Because studies so far have tested effects almost exclusively against bacteria, it is not known whether synergistic effects might be restricted to these infections or are more general, for example, also able to target protozoans.

Against this background, we studied the inhibitory effect of the three AMPs, Abaecin, Defensin and Hymenoptaecin, upon eight different genotypes, which we call ‘strains’, of the trypanosomatid C. bombi. We did not test the fourth AMP, Apidaecin, that is present in bumblebees for various technical reasons. We chose to use in vitro assays, as one advantage of this system is that C. bombi can be cloned and kept in culture, i.e. as strains. This eliminates the confounding effects of host background, which leads to substantial variation for the outcome depending on which strain (genotype) of C. bombi infects which host genetic background [44,45]. In fact, the expression of these AMPs depends on the host genetic background [16,46], the strain of the parasite [17] and the interaction of the two [47].

2. Material and methods

(a). Bumblebees and parasites

Queens of the bumblebee, B. terrestris, were captured in spring 2008 and 2010 in Aesch and Neunform (Northern Switzerland) and kept in the laboratory at 26°C under constant red light. The faeces of naturally infected queens were collected and single C. bombi cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting according to the protocol by Salathé & Schmid-Hempel [48]. These single cells were expanded in culture and frozen as clones that can be stored for many years without losing infectivity [48]. For the current study, these clones were re-cultured and maintained to form experimental clonal cultures in liquid ‘Full FP-FB medium’ at pH 5.8. Culture cells were kept in an incubator at 27°C and 3% CO2. Eight genotypically different C. bombi strains (clones) were used in this study. We selected strains with similar growth characteristics to maximally expose the effects of AMPs and their combinations. The strains' corresponding project tags were: 08068, 08161, 08075, 08261, 08076, 10208, 10361 and 08157. The cultures of parasite cells were always checked under the microscope for mortality or contamination prior to the assays. Contaminated cell cultures were excluded from the study.

(b). Antimicrobial peptides

Both Abaecin and Hymenoptaecin were custom synthesized by commercial services (EZBiolab, Carmel, IN, USA, and Activotec, Cambridge, UK, respectively). Defensin was synthesized by Jochen Wiesner at the Fraunhofer Institute (Giessen, Germany) by recombinant production [49,50]. As the genomic sequence of B. terrestris was not yet available at the time, mature peptide sequences were based upon prior peptide information from a closely related species, B. pascuorum [51], and EST information derived from B. terrestris [52]. Note that C. bombi also infects B. pascuorum; furthermore, it is in the meantime known that AMP genomic sequences are highly conserved across species [9]. Using these sequences (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1 and figure S6), Hymenoptaecin and Abaecin were synthesized to a purity of more than 96%. Defensin was synthesized to a purity of more than 90%. Peptides were stored in lyophilized form; for their use, the samples were suspended in sterile ddH20 to the appropriate peptide concentration chosen for the study (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM). The fourth bumblebee peptide, Apidaecin, proved to be very difficult to synthetize, at the time of study, owing to its chemical structure.

(c). Peptide assays

For the experimental assays, all eight C. bombi strains were tested for the effect of the peptides Abaecin, Defensin and Hymenoptaecin singly and in pairwise peptide combinations. The concentration of C. bombi cells was adjusted in fresh medium to a concentration of 80 000 cells ml−1 using a counting chamber (Cellometer Auto M10, Nexcelon Bioscience). For the tests, 80 µl of the Crithidia-inoculated medium was added to each well of a 96-well tissue culture plate (Sarstedt). Then an AMP-treatment matrix, as a combination of two AMPs each, was created. For this, 10 µl of each peptide with the corresponding final concentration (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM) was added to each well along the columns and rows, respectively, of the plate (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1). These concentrations are in the same range as other AMP concentrations found effective against other trypanosomes [53].

All pairwise concentrations of Abaecin, Defensin and Hymenoptaecin were assayed resulting in a total of 64 distinct concentration combinations for each two-peptide assay. Each of these distinct concentration combinations was replicated three times on different plates in order to balance plate effects. In addition, the physical positions of the treatments within the matrix were rotated across the plates for each replication to randomize the influence of spatial variation of the wells. After adding the Crithidia inoculum to each well, 10 µl of each peptide concentration was added to the inoculum according to the concentration scheduled for each plate. Blank wells containing Crithidia-free medium were also included in each plate to correct the measurement values. Plates were then kept in an incubator at 27°C and 3% CO2. To monitor parasite cell growth, optical density (OD) measurements were taken at 600 nm (absorbance wavelength) every 24 h for five consecutive days using a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader. Several previous calibrations had shown that OD is a good estimate for actual cell numbers in a well [54,55]. Concentrations used in the analyses were based on three experimental replicates for each strain.

(d). Data analysis

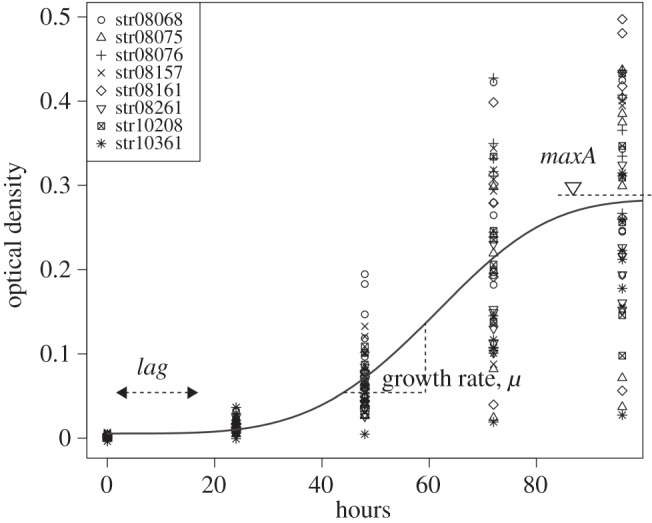

Statistical analyses were carried out with R v. 3.2.2 [56]. For each peptide combination treatment, cell numbers were measured at 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h from the start of the experiment. From this, the growth curve for each combination and replicate was estimated with R package grofit [57] by fitting a spline [57], for each replicate growth series, which yields three parameters—the lag phase (λ), maximum growth rate (robs), and maximum cell concentration (Amax) (figure 1). Here, we focus on this observed growth rate (robs); the analysis of the other parameters would have resulted in similar results and conclusions.

Figure 1.

Growth of C. bombi strains (str08068, … , str10631, see legend) under standard conditions (see Material and methods), with no AMPs present. The routine grofit() estimates three parameters by fitting a spline; lag (λ): the time lag to growth, growth rate (μ): the maximum growth rate, and maxA: the maximum level reached. Growth is measured photometrically as OD that correlates with cell numbers in the suspension. The curve follows a Weibull function and is for illustrative purposes only. Analyses reported here are based on the estimated growth rate (μ) for a particular strain and condition.

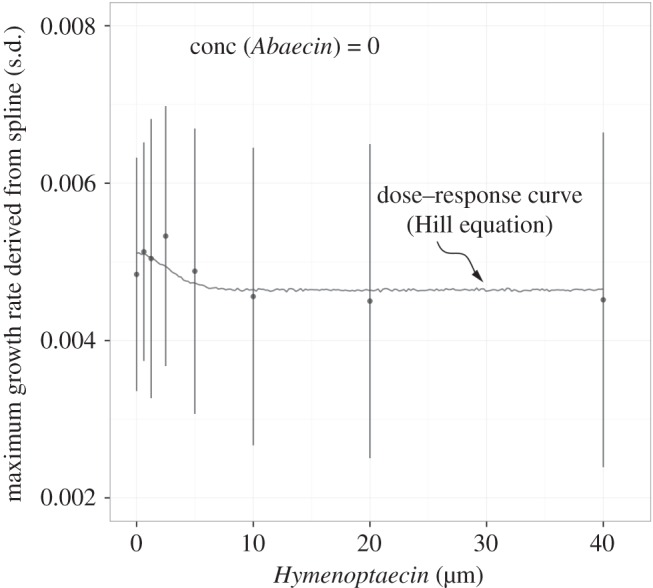

To calculate effects and expectations for synergy, we estimated a dose–response curve for each of the two AMPs (AMP1, AMP2) separately, that is, for cases where the concentration (i.e. the dose) of the other AMP was zero. The Hill equation was assumed, where the response (growth rate), r, for dose A of a single peptide is given as

| 2.1 |

Here, E(A) is the effect (in reducing growth rate) at dose A of the peptide, r(0) the growth rate when no AMP is present; Emax is the maximum effect of the peptide, h, the Hill coefficient describing the steepness of the curve, and A50 the dose that yields half of the maximum effect. The dose–response curves were estimated with a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm implemented with R package rjags [58]. Finally, we used equation (2.1) to convert the dose–response curves, r(A), into dose–effect curves, such that E(A) = r(0) − r(A), the effect of a single peptide at dose A.

With the effects, E(A1) and E(A2), of each single peptide in isolation at hand, we calculated the expectations for an interaction (e.g. synergistic) effect by assuming that the growth rate, r(A1, A2), under a combination of doses A1, A2 of the two AMPs is reduced by an amount equivalent to the combined effect of the peptides, E(A1, A2) [59]; hence:

| 2.2a |

The term E(A1, A2), describing the effect of the interaction on growth rate relative to the growth rate, r(0), when no AMPs are present, is of obvious interest. The zero growth rate r(0) was estimated from each of the experiments separately, i.e. matched to the given pairwise combination of AMPs.

If E(A1, A2) > 0, by definition, synergistic effects are present, because the combined effect reduces the growth of the parasite. Different concepts have been suggested to model this term [59]. Here, we followed two common reference models [60], i.e. Bliss Independence [61] and Loewe Additivity [62]. Bliss Independence is simple, and given as

| 2.2b |

Loewe Additivity is mathematically more involved and described in [59]; its implementation to the current data is detailed in the electronic supplementary material. Finally, we compared the expected growth rate, r(A1, A2), under the combined effect of two AMPs with the observed growth rate, robs, to derive conclusions about possible synergistic effects.

In addition, we fitted least-square surfaces to the observed growth rates, robs, that were estimated for any combination of AMPs, using the surf.ls and tsurf packages in R [63] to illustrate the effects of AMPs as a landscape in a combinatorial space of pairwise AMP concentrations.

3. Results

(a). Control growth

Each strain was grown independently in standard medium to estimate its growth parameters under conditions without the presence of AMPs (figure 1). These control values demonstrate the basic growth patterns of the strains. With respect to the estimated maximum growth rates from spline, the strains showed some albeit non-significant variation (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2). The best effect on various growth parameters when AMPs are used singly, varies among the strains tested and among the growth parameters measured.

(b). Effects of AMPs

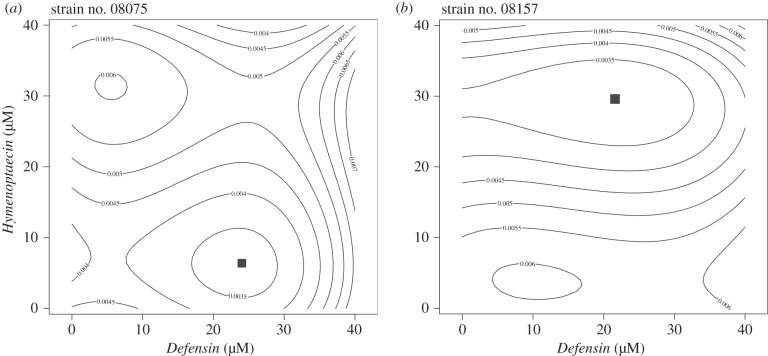

To illustrate the effect of AMPs alone or in combination, we fitted growth curves to every pairwise combination of AMPs and each replicate, as described in Material and methods (i.e. using splines in grofit). The resulting values were subsequently fitted with a least-square surface fit that generated contour plot landscapes (figure 2). These illustrate how various peptide combination concentrations affect parasite growth rate for a particular strain. Contour plot landscapes shown here were calculated as 3rd polynomial fit, as the model fit did not improve significance with the 4th and 5th polynomial order, and the 1st and 2nd order polynomial fits produced trivial outcomes. Figure 2 (see also the electronic supplementary material, figures S3 and S4) shows that each strain has a different landscape pattern as well as a distinct combination of AMP concentrations that produce the best effect (represented as the square point in the graph in figure 2). Table 1 summarizes the most effective pairwise combination of AMPs for each strain and for the mixture of pooled strains. The best effect on various growth parameters when AMPs are used singly varies among the strains tested and according to the growth parameters under scrutiny (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Figure 2.

Contour plots representing maximal growth rates (μ) of two different C. bombi strains when treated with Defensin and Hymenoptaecin. These contours reflect a least-square polynomial of 3rd order to fit the estimated maximal growth rate for each observed combination of AMPs (see Material and methods). Black squares denote the best effect, that is, the combination of AMPs that yields the lowest maximum growth rate for the strain. Each landscape represents the mean of three replicates for each strain (see also the electronic supplementary material, figures S3 and S4). The two strains shown here are (a) strain no. 08075 and (b) strain no. 08157.

Table 1.

Synopsis for the most effective pairwise combinations of AMPs (concentrations in micromolar), which maximally suppress the estimated growth rates (in OD/h) of eight tested C. bombi strains. These combinations are derived from least-square fitting of observed values (cf. figure 3). The values for ‘all (mixture)’ refer to the same calculations when all data are pooled regardless of strain; this reflects a mixture of strains by equal parts. The tested AMPs are: Abaecin, Defensin and Hymenoptaecin (Hymenopt.).

| best combination |

best combination |

best combination |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain no. | growth rate OD per h | Abaecin | Defensin | growth rate OD per h | Abaecin | Hymenopt. | growth rate OD per h | Defensin | Hymenopt. |

| 08068 | 0.003 | 40.0 | 35.2 | 0.003 | 29.6 | 23.2 | 0.002 | 30.4 | 23.2 |

| 08075 | 0.004 | 29.6 | 0 | 0.003 | 30.4 | 30.4 | 0.003 | 24.0 | 6.4 |

| 08076 | 0.005 | 26.4 | 10.4 | 0.000 | 31.2 | 29.6 | 0.005 | 33.6 | 21.6 |

| 08157 | 0.003 | 0 | 33.6 | 0.004 | 28.8 | 34.4 | 0.003 | 21.6 | 29.6 |

| 08161 | 0.002 | 31.2 | 40.0 | 0.004 | 27.2 | 32.0 | 0.003 | 40.0 | 23.2 |

| 08261 | 0.003 | 21.6 | 28.8 | 0.002 | 28.8 | 32.8 | 0.002 | 8.0 | 30.4 |

| 10208 | 0.006 | 0 | 29.6 | 0.004 | 31.2 | 33.6 | <0.001 | 40.0 | 35.2 |

| 10361 | 0.002 | 19.2 | 32.8 | 0.003 | 28.8 | 29.6 | 0.0005 | 16.8 | 0 |

| all (mixture) | 0.004 | 29.6 | 29.6 | 0.188 | 28.0 | 30.4 | 0.004 | 29.6 | 26.4 |

(c). Test for synergy

Even though it is possible to identify the combination of AMP concentrations that yields the best effect to reduce C. bombi growth rates, it does not follow that the AMPs necessarily act together synergistically (or antagonistically, for that matter). We tested this additional requirement by comparing the observed effects with the expected ones if the interaction followed either of two models—Bliss Independence and Loewe Additivity—as described in Material and methods, and in the contribution by Baeder et al. [59].

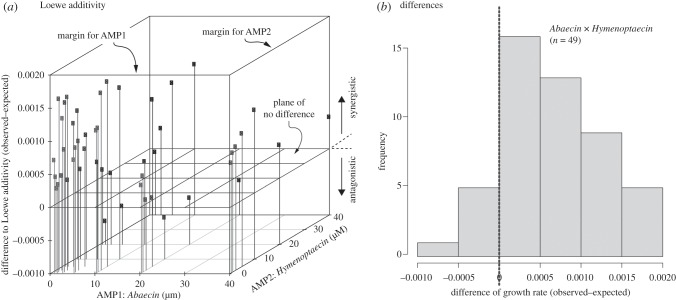

For this purpose, we first calculated the dose–response and dose–effect curves, respectively, if only one of the two AMPs is used (figure 3; the two margins of a given combination assay). As described in Material and methods, the Hill equation was fitted with MCMC in each of these cases. In this way, we derived dose–response and dose–effect curves for each margin of the two pairwise combined AMPs (Abaecin × Defensin, Abaecin × Hymenoptaecin and Defensin × Hymenoptaecin; figure 3; see also the electronic supplementary material, figure S5). In a second step, the predicted growth rates from the two margins of any pairwise assay were used to predict the growth rates if both AMPs are used (see Material and methods). For these predictions, we only used the interior combinations, that is, cases where both AMPs were used in concentrations greater than zero to ensure independence of the data; hence, we neglected the margins in the subsequent statistical analyses. Finally, we calculated the differences for all interior values (i.e. observed growth rates) relative to the predicted growth rates from either Bliss Independence or Loewe Additivity (e.g. figure 4a). The distribution of differences for a given case was then tested against an expectation of no difference, i.e. a distribution mean = 0 (figure 4b).

Figure 3.

A ‘margin’ (cf. figure 5) of the two-peptide combination assay. Shown are the observed means (dots, s.d.) of the estimated growth rates from spline when only one AMP (Hymenoptaecin) is varied across a range of concentrations (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM), and the other one (Abaecin) is not used. The line is the fitted Hill equation as a standard model for the dose–response curve (see Material and methods). At each concentration, three replicates were measured. The dose–response curve was subsequently used to calculate the expectations for a combined use of the two peptides.

Figure 4.

Example of Loewe Additivity. (a) Three-dimensional view of the difference between observed and predicted growth rates when Loewe Additivity is assumed. Most of the points are above the zero plane (of no difference), indicating that synergistic interaction of the two peptides Abaecin (AMP1) and Hymenoptaecin (AMP2) is the case. The two front faces of the cube represent the two ‘margins’ (AMP1, AMP2) of the problem, i.e. cases where only one AMP is varied and the other peptide is not applied (concentration = 0). Note that only ‘interior’ cases, i.e. where both of the two AMPs are used with concentrations > 0 are included in the predictions to ensure independence. (b) Histogram of differences of observed—predicted growth rates as plotted in (b). The difference is significantly different from zero (i.e. no additional effect of peptide combination; t = 15.06, d.f. = 48, p < 0.0001). Because the mean difference is above zero, the two peptides act synergistically according to Loewe Additivity. The graph is for all strains combined.

With few exceptions, all differences were significantly different from zero, i.e. no interaction (table 2). This was true when differences were calculated for every strain separately, as well as for the ‘mixture’ of strains, i.e. the pooled data for all strains. In particular, Bliss Independence, with one exception (strain no. 08261 with the combination of Abaecin × Hymenoptaecin) always suggested significant positive deviations from expectation, that is, synergistic interactions. With Loewe Additivity, the picture was less clear. In the majority of cases, significant positive deviations were found (i.e. synergy). However, only under Loewe Additivity, six cases of significant negative deviations were found, indicating antagonistic interactions, especially for the pair Defensin × Hymenoptaecin. Together, the deviations from predicted were smaller for Loewe Additivity than for Bliss Independence; this difference was significant, albeit marginally so for the pairs Abaecin × Defensin and Abaecin × Hymenoptaecin. Most notably, all strains differed among each other in their deviations from the predicted growth rates under both interaction models (electronic supplementary material, table S5). Hence, the overall pattern seems to be synergism with sometimes reverse effects especially in the pair Defensin × Hymenoptaecin, depending on the strain of C. bombi.

Table 2.

Summary of differences (d) between observed and predicted growth rates for different pairwise combinations and interaction models. Differences (d) in growth rate, compared to predicted, are given in 10−3·OD change per hour. Antagonistic differences are in italics (n.s., non-significant).

| combination |

Abaecin

×

Defensin |

Abaecin

×

Hymenoptaecin |

Defensin

×

Hymenoptaecin |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain no. | Bliss d |

Loewe d |

Bliss d |

Loewe d |

Bliss d |

Loewe d |

| 08068 | 0.63*** (t48 = 19.28) |

0.42*** (t48 = 53.45) |

1.77*** (t48 = 42.24) |

1.51*** (t48 = 198.75) |

1.07*** (t48 = 24.32) |

0.70*** (t48 = 135.59) |

| 08075 | 1.86*** (t48 = 45.58) |

1.52*** (t48 = 250.67) |

2.68*** (t48 = 18.43) |

1.99*** (t48 = 36.33) |

1.92*** (t48 = 26.69) |

0.84*** (t48 = 26.69) |

| 08076 | 0.37*** (t48 = 5.95) |

−1.35*** (t48 = 11.34) |

0.89*** (t48 = 14.21) |

0.28*** (t48 = 14.21) |

1.13*** (t48 = 11.60) |

— |

| 08157 | 0.49*** (t48 = 7.13) |

0.03 n.s. (t48 = 1.82) |

1.39*** (t48 = 10.12) |

0.61 *** (t48 = 18.40) |

0.88*** (t48 = 9.28) |

0.6 *** (t48 = 31.14) |

| 08161 | 1.48*** (t48 = 28.84) |

1.14*** (t48 = 112.99) |

3.65*** (t48 = 44.89) |

3.01*** (t48 = 306.79) |

1.67*** (t48 = 7.77) |

−0.17*** (t48 = 6.09) |

| 08261 | 1.44*** (t48 = 29.48) |

0.99*** (t48 = 189.69) |

0.03 n.s. (t48 = 0.56) |

−0.27*** (t48 = 120.32) |

0.31*** (t48 = 6.87) |

−0.02 * (t48 = 2.11) |

| 10208 | 1.69*** (t48 = 14.26) |

0.69*** (t48 = 46.51) |

0.64*** (t48 = 8.42) |

0.23*** (t48 = 15.68) |

0.50*** (t48 = 3.46) |

−0.43*** (t48 = 15.74) |

| 10361 | 2.36*** (t48 = 29.13) |

1.84*** (t48 = 103.27) |

0.30*** (t48 = 5.19) |

−0.20*** (t48 = 28.06) |

1.26*** (t48 = 22.82) |

0.92*** (t48 = 74.82) |

| all (mixture) | 1.05*** (t48 = 19.42) |

0.88*** (t48 = 15.06) |

0.92*** (t48 = 10.51) |

−0.60*** (t48 = 7.59) |

0. 57*** (t48 = 6.39) |

0. 04 n.s. (t48 = 0.57) |

| variation among strains | F7,9792 = 2357.4*** | F7,9792 = 47 780*** | F7,9792 = 4249.7*** | F7,9792 = 31 874*** | F7,9792 = 381.61*** | F6,8568 = 9678.7*** |

| Bliss versus Loewe: Welch t95.41 = 2.12* |

Bliss versus Loewe: Welch t95.99 = 2.11 |

Bliss versus Loewe: Welch t88.09 = 4.81*** |

||||

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

AMPs are known to be effective against flagellated protozoan parasites, such as against the trypanosomes. Examples include Leishmania major, Trypanosoma cruzi and T. brucei [21,53,64]. Similarly, insects when becoming infected with trypanosomes upregulate the expression of AMPs; examples include tsetse flies [64,65] and bumblebees [16,46,66]. Where the effect of AMPs has been tested, the effective concentration needed to kill parasites is in the range used in our study (e.g. [53]).

The concept of synergistic interactions is not entirely new and has been discussed especially in the context of vertebrate innate immune defences [5,67]. For example, mammalian cationic AMPs act synergistically against bacteria including antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains [68]. But synergistic effects have been reported across a wide range of taxa, including oysters [36], beetles [49], hemiptera [69], honeybees [39], bumblebees [43], humans [70] and plants [71]. Often, in these studies, the effect is tested against bacteria, and in some cases, the synergy is observed with regard to effectors (e.g. trypsin inhibitors [71]) other than AMPs.

Also for trypanosomes, synergistic effects are known, for example, against the agent of Chagas disease, T. cruzi [69]. The parasite used here, C. bombi, is phylogenetically close to Leishmania [72]. Therefore, two sources of insight of how the AMPs used here may act against C. bombi are available. On the one hand, Rahnamaeian et al. [43] showed that Hymenoptaecisn and Abaecin act together to permeabilize the cell membrane and block the DNA replication machinery, respectively. For Leishmania, the effect of AMPs seems rather complex and includes membrane disruption, the induction of apoptosis, effects on intracellular targets including mitochondrial functions, as well as immuno-modulation in the host [20,53,73]. Hence, it is likely that bumblebee AMPs permeabilize the membranes of trypanosomes such as Crithidia as well, and interfere with intracellular processes, but their exact mode of action must await further study.

With regard to our initial question of whether AMPs can be used in combinations to kill C. bombi, we clearly find that this is the case. Furthermore, in contrast to most earlier studies, here we explicitly define models for synergistic interactions, namely Bliss Independence and Loewe Additivity against which the observed combinatorial effects can be compared. With these tools, we find that the most effective concentrations of AMPs are, firstly, within the experimental range of concentrations chosen (0–40 µM; cf. figure 3) and, secondly, that the most effective combination is typically ‘inside’ the tested frame as illustrated in figure 2 and listed in table 1. In other words, the best effect of a combination of two peptides is not necessarily achieved when the maximum concentration for each of the peptides is applied. These findings are in line with the idea that AMPs are functionally dependent on one another. The example is Abaecin, which prepares the ground for Hymenoptaecin to enter the parasite cell; whereas Abaecin on its own has little effect.

The idea that—in eukaryotes—selection on regulatory sequences and elements, in addition or instead of change in the structural gene sequences, is a main driver for the evolution of form and structure has gained hold and support over the last decades [74–79], even though conserved function despite sequence differences may often be difficult to detect [80]. Clearly then, variation in the expression of genes coding for immune effectors, such as AMPs, rather than sequence variation in the genes themselves is an alternative strategy to control and eliminate highly variable parasites [16,47]. The parasite studied here, C. bombi, is indeed highly variable such that every host individual virtually carries its own infecting parasite genotypes (strains) [44,45,81,82]. We have no insight, as yet, whether such variable, fluctuating selection pressure exerted by parasites could also be responsible for the relatively rapid loss and gain of AMP gene families during evolution [25,28]. Because such fluctuating selection unfolds over short ecological time scales—typically much faster than the time scales of gene duplications and losses—it is possible that maintenance of polymorphism by, for example, allelic variation is more relevant and would manifest itself as patterns of balancing selection [29].

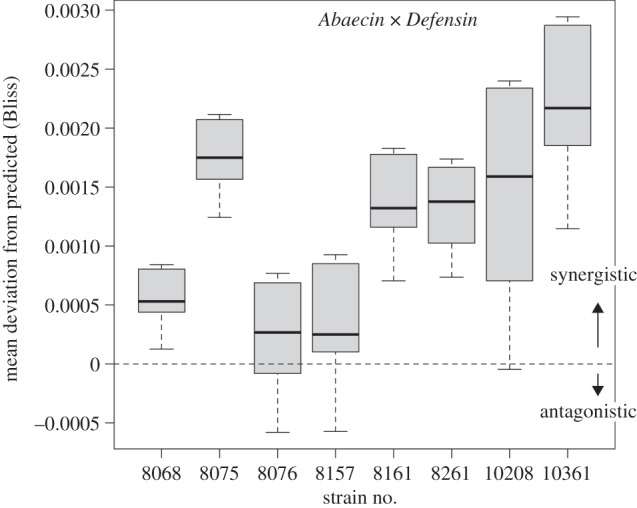

Yet, the existence of hidden polymorphism in AMPs [29] does not preclude the possibility that hosts respond to infection by expressing appropriate cocktails of AMPs. In fact, bumblebee hosts express a mixture of AMPs depending both on their genetic background (i.e. the colony) and on the infecting strain [47]. Hence, a reasonable conjecture is that hosts tend to express the most effective mixture of AMPs that fits the current infection. We cannot test this conjecture here with the available data, not least because expression levels are not always identical to the level of circulating proteins (AMPs). However, the conjecture would also predict that a given combination of AMPs affects different parasite strains differently. This seems indeed to be the case (cf. figure 2). Furthermore, we should expect that strains vary in the deviation of observed effect versus the predicted interaction effect according to Bliss Independence or Loewe Additivity. This we also found in our study (cf. figure 5) and should reflect the fact that strains vary in their sensitivity towards the interaction effect of a given combination of AMPs.

Figure 5.

Boxplot of deviations from the predicted Bliss Independence across the tested C. bombi strains. In his example, the graph refers to the pairwise combinations of Abaecin and Defensin. Overall, the deviations from zero are for all strains, indicating synergy, and the variation among strains is highly significant, too (F7,9792 = 2357.4, p < 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Andreas Vilcinskas and Jochen Wiesner (Frauenhofer Institute for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology, Dep. Bioresources, Giessen) for the synthesis of the Defensin peptide, modelled after T. castaneum. We also would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. Christine Reber, Regula Schmid-Hempel, Elke Karaus and Dani Heinzmann helped with the laboratory work. Roland Regös and Desirée Bäder provided the algorithms for calculating the Hill curves and Loewe Additivity.

Data accessibility

Data are summarized in the text and electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

M.M., V.V. and P.S.-H. designed and carried out the study, and analysed the data. M.M. and P.S.-H. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The authors were financially supported by an ERC Advanced grant (no. 268853 RESIST) to P.S.H.

References

- 1.Bulet P, Stöcklin R, Menin L. 2004. Anti-microbial peptides: from invertebrates to vertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 198, 169–184. ( 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0124.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai Y, Gallo RL. 2009. AMPed up immunity: how antimicrobial peptides have multiple roles in immune defense. Trends Immunol. 30, 131–141. ( 10.1016/j.it.2008.12.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen LT, Haney EF, Vogel HJ. 2011. The expanding scope of antimicrobial peptide structures and their modes of action. Trends Biotechnol. 29, 464–472. ( 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahnamaeian M. 2011. Antimicrobial peptides: modes of mechanism, modulation of defense responses. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1325–1332. ( 10.4161/psb.6.9.16319) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zasloff M. 2013. Antimicrobial peptides. New York, NY: John Wiley & Son. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilcinskas A, Mukherjee K, Vogel H. 2013. Expansion of the antimicrobial peptide repertoire in the invasive ladybird Harmonia axyridis. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20122113 ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.2113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans JD et al. 2006. Immune pathways and defence mechanisms in honey bees Apis melifera. Insect Mol. Biol. 15, 645–656. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00682.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadd BM, et al. 2015. The genomes of two key bumblebee species with primitive eusocial organization. Genome Biol. 16, 76 ( 10.1186/s13059-015-0623-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barribeau SM, et al. 2015. A depauperate immune repertoire precedes evolution of sociality in bees. Genome Biol. 16, 83 ( 10.1186/s13059-015-0628-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Windsor DA. 1988. Most of the species on earth are parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 28, 1939–1941. ( 10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00153-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett MP, Burchmore RJS, Stich A, Lazzari JO, Frasch AC, Cazzulo JJ, Krishna S. 2003. The trypanosomiases. Lancet 362, 1469–1480. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14694-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brun R, Blum J, Cahppuis F, Burri C. 2010. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet 375, 9–15. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60829-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid-Hempel P. 2001. On the evolutionary ecology of host-parasite interactions—addressing the questions with bumblebees and their parasites. Naturwissenschaften 88, 147–158. ( 10.1007/s001140100222) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown MJF, Loosli R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2000. Condition-dependent expression of virulence in a trypanosome infecting bumblebees. Oikos 91, 421–427. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.910302.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown MJF, Schmid-Hempel R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2003. Strong context-dependent virulence in a host–parasite system: reconciling genetic evidence with theory. J. Anim. Ecol. 72, 994–1002. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00770.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riddell CR, Adams S, Schmid-Hempel P, Mallon EB. 2009. Differential expression of immune defences is associated with specific host–parasite interactions in insects. PLoS ONE 4, e7621 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0007621) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barribeau SM, Schmid-Hempel P. 2013. Qualitatively different immune response of the bumblebee host, Bombus terrestris, to infection by different genotypes of the trypanosome gut parasite, Crithidia bombi. Infect. Genet. Evol. 20, 249–256. ( 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshwal S, Mallon EB. 2014. Antimicrobial peptides play a functional role in bumblebee anti-trypanosome defense. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 42, 240–243. ( 10.1016/j.dci.2013.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulet P, Hetru C, Dimarq J-L, Hoffman D. 1999. Anti-microbial peptides in insects; structure and function. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 23, 329–344. ( 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00015-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bera A, Singh S, Nagaraj R, Vaidya T. 2003. Induction of autophagic cell death in Leishmania donovani by antimicrobial peptides. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 127, 23–35. ( 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00300-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGwire BS, Olson CL, Tack BF, Engman DM. 2003. Killing of African trypanosomes by antimicrobial peptides. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 146–152. ( 10.1086/375747) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennessen JA. 2005. Molecular evolution of animal antimicrobial peptides: widespread moderate positive selection. J. Evol. Biol. 18, 1387–1394. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00925.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark AG, Wang L. 1997. Molecular population genetics of Drosophila immune system genes. Genetics 147, 713–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiggins FM, Kim K-W. 2005. The evolution of antifungal peptides in Drosophila. Genetics 171, 1847–1859. ( 10.1534/genetics.105.045435) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sackton TB, Lazzaro BP, Schlenke TA, Evans JD, Hultmark D, Clark AG. 2007. Dynamic evolution of the innate immune system in Drosophila. Nature Genetics 39, 1461–1468. ( 10.1038/ng.2007.60) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obbard DJ, Welch JJ, Kim K-W, Jiggins FM. 2009. Quantifying adaptive evolution in the Drosophila immune system. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000698 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000698) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazzaro BP. 2008. Natural selection on the Drosophila antimicrobial immune system. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 284–289. ( 10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waterhouse RM, et al. 2007. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science 316, 1738–1743. ( 10.1126/science.1139862) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unckless R, Lazzaro BP. 2016. The potential for adaptive maintenance of diversity in insect antimicrobial peptides. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150291 ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.291) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulmer MS, Crozier RH. 2005. Variation in positive selection in termite GNBPs and Relish. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 317–326. ( 10.1093/molbev/msj037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viljakainen L, Evans JD, Hasselmann M, Rueppell O, Tingek S, Pamilo P. 2009. Rapid evolution of immune proteins in social insects. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1791–1801. ( 10.1093/molbev/msp086) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erler S, Lhomme P, Rasmont P, Lattorff HMG. 2014. Rapid evolution of antimicrobial peptide genes in an insect host–social parasite system. Infect. Genet. Evol. 23, 129–137. ( 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCafferty DG, Cudic P, Yu MK, Behenna DC, Kruger R. 1999. Synergy and duality in peptide antibiotic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 672–680. ( 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)00025-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SS, Kim S, Kim E, Hyun B, Kim K-K, Lee BJ. 2003. Synergistic Inhibitory effect of cationic peptides and antimicrobial agents on the growth of oral Streptococci. Caries Res. 37, 425–430. ( 10.1159/000073394) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenfeld Y, Barra D, Simmaco M, Shai Y, Mangoni ML. 2006. A synergism between temporins toward Gram-negative bacteria overcomes resistance imposed by the lipopolysaccharide protective layer. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 28 565–28 574. ( 10.1074/jbc.M606031200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gueguen Y, Romestand B, Fievet J, Schmitt P, Destoumieux-Garzón D, Vandenbulcke F, Bulet P, Bachère E. 2009. Oyster hemocytes express a proline-rich peptide displaying synergistic antimicrobial activity with a defensin. Mol. Immunol. 46, 516–552. ( 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mangoni ML, Shai Y. 2009. Temporins and their synergism against Gram-negative bacteria and in lipopolysaccharide detoxification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 1610–1619. ( 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassone M, Otvos L Jr. 2010. Synergy among antibacterial peptides and between peptides and small-molecule antibiotics. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Therap. 8, 703–716. ( 10.1586/eri.10.38) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romanelli A, Moggio L, Montella RC, Campiglia P, Iannaccone M, Capuano F, Pedonea C, Capparelli R. 2010. Peptides from Royal Jelly: studies on the antimicrobial activity of jelleins, jelleins analogs and synergy with temporins. Pept. Sci. 17, 348–352. ( 10.1002/psc.1316) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chongsiriwatana NP, Wetzler M, Barron AE. 2011. Functional synergy between antimicrobial peptoids and peptides against Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 5399–5402. ( 10.1128/AAC.00578-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dosler S, Gerceker AA. 2012. In vitro activities of antimicrobial cationic peptides; melittin and nisin, alone or in combination with antibiotics against Gram-positive bacteria. J. Chemother. 24, 137–143. ( 10.1179/1973947812Y.0000000007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pöppel A-K, Vogel H, Wiesner J, Vilcinskas A. 2015. Antimicrobial peptides expressed in medicinal maggots of the blow fly Lucilia sericata show combinatorial activity against bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 2508–2514. ( 10.1128/AAC.05180-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahnamaeian M, et al. 2015. Insect antimicrobial peptides show potentiating functional interactions against Gram-negative bacteria. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20150293 ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.0293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmid-Hempel P, Puhr K, Kruger N, Reber C, Schmid-Hempel R. 1999. Dynamic and genetic consequences of variation in horizontal transmission for a microparasitic infection. Evolution 53, 426–434. ( 10.2307/2640779) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmid-Hempel P, Reber Funk C. 2004. The distribution of genotypes of the trypanosome parasite, Crithidia bombi, in populations of its host, Bombus terrestris. Parasitology 129, 147–158. ( 10.1017/S0031182004005542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunner FS, Schmid-Hempel P, Barribeau SM. 2012. Immune gene expression patterns in Bombus terrestris reveal signatures of infection despite strong variation among populations, colonies, and sister workers. PLoS ONE 8, e68181 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0068181) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barribeau SM, Sadd BM, du Plessis L, Schmid-Hempel P. 2014. Gene expression differences underlying genotype-by-genotype specificity in a host–parasite system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3496–3501. ( 10.1073/pnas.1318628111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salathé R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2012. Probing mixed-genotype infections I: Extraction and cloning of infections from hosts of the trypanosomatid Crithidia bombi. PLoS ONE 7, e49046 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0049046) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajamuthiah R, Jayamani E, Conery AL, Burgwyn Fuchs B, Kim W, Johnston T, Vilcinskas A, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E. 2015. A defensin from the model beetle Tribolium castaneum acts synergistically with Telavancin and Daptomycin against multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 10, e0128576 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0128576) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tonk M, Knorr E, Cabezas-Cruz A, Valdés JJ, Kollewe C, Vilcinskas A. 2015. Tribolium castaneum defensins are primarily active against Gram-positive bacteria. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 132, 208–215. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2015.10.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rees JA, Moniatte M, Bulet P. 1997. Novel antibacterial peptides isolated from a European bumblebee, Bombus pascuorum (Hymenoptera, apoidea). Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 27, 413–422. ( 10.1016/S0965-1748(97)00013-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadd BM, Kube M, Klages S, Reinhardt R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2010. Analysis of a normalised expressed sequence tag (EST) library from a key pollinator, the bumblebee Bombus terrestris. BMC Genom. 11, 110 ( 10.1186/1471-2164-11-110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGwire BS, Kulkarni MM. 2010. Interactions of antimicrobial peptides with Leishmania and trypanosomes and their functional role in host parasitism. Exp. Parasitol. 126, 397–405. ( 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ulrich Y, Sadd BM, Schmid-Hempel P. 2011. Strain filtering and transmission of a mixed infection in a social insect. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 354–362. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02172.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marxer M, Barribeau SM, Schmid-Hempel P. 2016. Experimental evolution of a trypanosome parasite of bumblebees and its implications for infection success and host immune response. Evol. Biol. ( 10.1007/s11692-015-9366-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Core Team. 2015. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kahm M, Hasenbrink G, Lichtenberg-Fraté H, Ludwig J, Kschischo M. 2010. grofit: Fitting biological growth curves with R. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–21. ( 10.18637/jss.v033.i07)20808728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plummer M. 2015. rjags: Bayesian Graphical Models using MCMC. R package version 3-15. CRAN Repository, http://mcmc-jags.sourceforge.net.

- 59.Baeder DY, Yu G, Hozé N, Rolff J, Regoes RR. 2016. Antimicrobial combinations: Bliss independence and Loewe additivity derived from mechanistic multi-hit models. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150294 ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0294) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greco WR, Bravo G, Parsons J. 1995. The search for synergy: a critical review from a response surface perspective. Pharmacol. Rev. 47, 331–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bliss CI. 1939. The toxicity of poisons applied jointly. Ann. Appl. Biol. 26, 585–615. ( 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1939.tb06990.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loewe S, Muischenk H. 1926. Über Kombinationswirkungen. I. Mitteilung: Hilfsmittel der Fragestellung. Naunyn-Schneiderbergs Archive für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 114, 313–326. ( 10.1007/BF01952257) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ripley BD. 1981. Spatial statistics. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boulanger N, Bulet P, Lowenberger CA. 2006. Antimicrobial peptides in the interactions between insects and flagellate parasites. Trends Parasitol. 22, 262–268. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2006.04.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boulanger N, Brun R, Ehret-Sabatier L, Kunz C, Bulet P. 2002. Immunopeptides in the defense reactions of Glossina morsitans to bacterial and Trypanosoma brucei brucei infections. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 369–375. ( 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00029-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riddell CE, Sumner S, Adams S, Mallon EB. 2011. Pathways to immunity: temporal dynamics of the bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) immune response against a trypanosome gut parasite. Insect Mol. Biol. 20, 529–540. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01084.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matsuzaki K, Mitani Y, Akada K-Y, Murase O, Yoneyama S, Zasloff M, Miyajima K. 1998. Mechanism of synergism between antimicrobial peptides Magainin 2 and PGLa. Biochemistry 37, 15 144–15 153. ( 10.1021/bi9811617) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan H, Hancock REW. 2001. Synergistic interactions between mammalian antimicrobial defense peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1558–1560. ( 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1558-1560.2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fieck A, Hurwitz I, Kang AS, Durvasula R. 2010. Trypanosoma cruzi: synergistic cytotoxicity of multiple amphipathic anti-microbial peptides to T. cruzi and potential bacterial hosts. Exp. Parasitol. 125, 342–437. ( 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.02.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nagaoka I, Hirota S, Yomogida S, Ohwada A, Hirata M. 2000. Synergistic actions of antibacterial neutrophil defensins and cathelicidins. Inflamm. Res. 49, 73–79. ( 10.1007/s000110050561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Terras F, Schoofs H, Thevissen K, Osborn R, Vanderley DJ, Cammue B, Broekaert WF. 1993. Synergistic enhancement of the anti- fungal activity of wheat and barley thionins by radish and oilseed rape 2S albumins and by barley trypsin inhibitors. Plant Physiol. 103, 1311–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmid-Hempel R, Tognazzo M. 2010. Molecular divergence defines two distinct lineages of Crithidia bombi (Trypanosomatidae), parasites of bumblebees. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 57, 337–345. ( 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2010.00480.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marr AK, McGwire BS, McMaster WR. 2012. Modes of action of Leishmanicidal antimicrobial peptides. Future Microbiol. 7, 1047–1059. ( 10.2217/fmb.12.85) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carroll SB. 2005. Evolution at two levels: on genes and form. PLoS Biol. 3, 1159–1116. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030245) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim J, He X, Sinha S. 2007. Evolution of regulatory sequences in 12 Drosophila species. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000330 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000330) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prud'homme B, Gompel N, Carroll SB. 2007. Emerging principles of regulatory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 8605–8612. ( 10.1073/pnas.0700488104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meireles-Filho ACA, Stark A. 2009. Comparative genomics of gene regulation—conservation and divergence of cis-regulatory information. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 550–570. ( 10.1016/j.gde.2009.10.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berezikov E. 2011. Evolution of microRNA diversity and regulation in animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 846–860. ( 10.1038/nrg3079) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.He BZ, Holloway AK, Maerkl SJ, Kreitman M. 2011. Does positive selection drive transcription factor binding site turnover? A test with Drosophila cis-regulatory modules. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002053 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weirauch MT, Hughes TR. 2009. Conserved expression without conserved regulatory sequence: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Trends Genet. 26, 66–74. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2009.12.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schmid-Hempel R, Tognazzo M, Salathé R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2011. Genetic exchange and emergence of novel strains in directly transmitted trypanosomatids. Genet. Evol. 11, 564–571. ( 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.01.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tognazzo M, Schmid-Hempel R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2012. Probing mixed-genotype infections II: high multiplicity in natural infections of the trypanosomatid, Crithidia bombi, in its host, Bombus spp. PLoS ONE 7, e49137 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0049137) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are summarized in the text and electronic supplementary material.