Abstract

Pyrophosphate (PPi) is a critical element of cellular metabolism as both an energy donor and as an allosteric regulator of several metabolic pathways. The apicomplexan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, uses PPi in place of ATP as an energy donor in at least two reactions: the glycolytic PPi-dependent phosphofructokinase (PFK), and the proton translocating vacuolar pyrophosphatase (V-H+-PPase). In the present work, we report the cloning, expression, and characterization of a cytosolic pyrophosphatase from T. gondii (TgPPase). Amino acid sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis indicates that the gene encodes a family I soluble PPase. Overexpression of the enzyme in extracellular tachyzoites led to a 6- fold decrease in the cytosolic concentration of PPi relative to RH wild type tachyzoites. Unexpectedly, this subsequent reduction in pyrophosphate was associated with a higher glycolytic flux in the overexpressing mutants as evidenced by higher rates of proton and lactate extrusion. In addition to elevated glycolytic flux, TgPPase overexpressing tachyzoites also possessed higher ATP concentrations relative to wild type, RH parasites. These results implicate PPi as having a significant regulatory role in glycolysis and potentially other downstream processes that regulate growth and cell division.

INTRODUCTION

Pyrophosphate (PPi) is a byproduct of many biosynthetic reactions (synthesis of nucleic acids, coenzymes, proteins, isoprenoids, and activation of fatty acids), and it has been proposed that the removal of PPi by pyrophosphatases (PPases) makes biosynthetic reactions thermodynamically favorable [1]. In addition, bioenergetic and regulatory roles of PPi have been suggested [2]. PPi can be generated by photophosphorylation, oxidative phosphorylation, and glycolysis, and can be used in a number of reactions to replace ATP [3].

The cytosolic concentration of PPi is regulated in higher organisms, predominantly through the activity of soluble cytosolic PPases [4]. Inorganic PPases include membrane-bound H+- pumping PPases (V-H+-PPases) and soluble form PPases. The membrane-bound V-H+-PPases utilize the energy released by hydrolysis of PPi to transport protons across the membrane of cells or organelles [5–8]. The soluble inorganic PPases that hydrolyze PPi to inorganic phosphate (Pi), are essential enzymes, and have high activity in the cytoplasm. The absence of these PPases would lead to the buildup of toxic levels of PPi, accounting for the essential nature of the enzymes. Two families of nonhomologous soluble inorganic PPases have been described: family I PPases, which are widespread in all types of organisms and prefer Mg2+ as cofactor [9, 10], and family II PPases, which are exclusive to bacteria and prefer Mn2+ as cofactor [9–11]. One of the most studied family I PPases is that from Saccharomyces cerevisiae [12]. In addition to its PPase activity this enzyme displays polyphosphatase activity in the presence of transition metal ions such as Zn2+, Mn2+ and Co2+ as cofactors, [13–16], and it also can hydrolyze organic tri- and diphosphates, such as ATP and ADP [16–18].

An unusual characteristic of Toxoplasma gondii, a major opportunistic pathogen of fetuses from recently infected mothers and of patients with AIDS, is that it possesses cellular levels of PPi that are higher than those of ATP [19]. In addition, it stores PPi and poly P in acidic organelles named acidocalcisomes [20–22]. Acidocalcisomes have been found in a number of organisms from bacteria to man [23]. Acidocalcisomes from T. gondii are characterized by their electron density, high content of cations bound to PPi and poly P, and a number of pumps in their membranes, among them a V-H+-PPase, which contributes to their acidification [20–22, 24]. Incubation of fixed Trypanosoma cruzi [25] or T. evansi [26] cells with a PPase removes the electron dense matrix of acidocalcisomes, which indicates that PPi is an important component of this organelle’s structure. In addition to its use by the acidocalcisomal V-H+-PPase [21, 27], T. gondii PPi can also be used in place of ATP as an energy donor in the PPi-dependent phosphofructokinase (PFK) reaction [28].

In this work we characterized biochemically a soluble PPase and named it TgPPase. By overexpressing this enzyme in T. gondii tachyzoites we were able to isolate clones with up to 10 times higher enzymatic activity than wild type cells. This high cytosolic PPase activity altered the cytosolic concentration of PPi, which was significantly reduced when compared to the cytosolic level in RH wild type tachyzoites. These mutant cells showed alterations in their glycolytic pathway leading us to propose a regulatory role of PPi on the glycolytic pathway of these parasites.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals and Reagents

Aminomethylenediphosphonate (AMDP) was synthesized by Michael Martin (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, reverse transcriptase, Taq polymerase, DNA ladder, Trizol reagent, and goat serum were from GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). The pET28a+ expression system, Ni-NTA HisBind resin, and benzonase nuclease were from Novagen Inc. (Madison, WI). pCR2.1-TOPO cloning kit, secondary antibodies, BCECF and BCECF-AM were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Hybond-N nylon membrane, HiTrap desalting column and ECL™ chemiluminescence kit were obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). All other reagents were analytical grade.

Culture Methods

T. gondii tachyzoites (RH) were grown in hTERT host cells using described protocols and bradyzoites were obtained by differentiation of tachyzoites of the ME49 strain as described before [29]. Transgenic fluorescent T. gondii tachyzoites expressing a YFPYFP fusion gene were a gift from Dr. Boris Striepen (University of Georgia, Athens) [30].

T. gondii growth measurements

[3H]Uracil incorporation was conducted in hTert cells that were cultured in 12-well plates for 24 h before they were challenged with 1×105 tachyzoites per well. [3H]uracil incorporation was measured 24 h later by measuring the amount of [3H]uracil incorporated into each well during the last 4 h [31] [32]. T. gondii plaque assays were performed as previously described [33]. Assays were conducted in 6-well plates each containing a confluent layer of hTERT host cells. Parasites (200 per well) were incubated for 9 days to allow invasion and replication (formation of plaques). Plaque number and relative plaque area (i.e., percent of total area occupied by a plaque forming unit) were determined using ImageJ software (NIH).

TgPPase cDNA Cloning by 5’ and 3’-RACE

The protein sequence of the T. brucei soluble inorganic PPase (NCBI GenBank protein accession number AAP74702) was used to search the T. gondii genome database revealing three polypeptides sharing high similarity to known soluble inorganic PPases. The 5’ and 3’-RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) technique was used to sequence the 5’ and 3’ ends of the TgPPase cDNA, using information from known contigs and EST sequences. The Invitrogen Life Technologies kit for 5’ and 3’ RACE was used.

Database Search and Phylogenetic Analysis

BLAST analysis of the TgPPase protein against the OrthoMCL database (version 2) (www.orthomcl.org/cgi-bin/OrthoMclWeb.cgi) was done to search for putative PPase orthologs. A multiple sequence alignment from the sequences obtained was created by ClustalW [34] and optimized using GeneDoc (version 2.6.002) [35] and MacClade (version 4.06) [36].

Phylogenetic trees were built based on the optimized alignment using the parsimony and distance methods from the Felsenstein PHYLIP package (version 3.65). Briefly, 100 alignment replicates were created by the bootstrap method using the SEQBOOT program [37, 38]. The bootstrapped dataset was used to generate trees by the parsimony method using the PROTPARS program. For calculating distance, PROTDIST was used to generate 100 matrices from the bootstrapped dataset, by applying the Dayhoff PAM evolutionary model of amino acid substitutions [39]. One-hundred distance trees were built by the Neighbor-joining method [40]. The final consensus trees were built using the majority rule and visualized using TreeViewX (version 0.4) and Mega 3.1 (version 3.1) [41].

Isolation of Cells Overexpressing TgPPase

The TgPPase gene was amplified using the primers (5’-AGATCTATGCAGTCTGCACCTCTGGC-3’ and 5’- CCTAGGCGGTAGCCACAACTTTTG-3’) with the BglII and AvrII restriction enzyme sites (underlined) by RT-PCR. The PCR products were cloned into the expression vectors pTubP30-flag/sagCAT (a gift from Dr William Sullivan, Indiana University School of Medicine) [42] replacing the P30 gene. The resulting construct pTub-TgPPase-flag/sagCAT was sequenced and use for transfection of T. gondii tachyzoites using published protocols [33]. Selection was done with 20 µM chloramphenicol. Cloning was performed by limited dilution and one clone was selected for further analysis and named TgPPase-OE. A clone expressing two copies of the YFP gene was used for immunofluorescence co-localization assays [30].

Preparation of Recombinant TgPPase

The whole ORF of TgPPase was amplified by RT-PCR with the primers 5’-CATATGCAGTCTGCACCTCTGGC-3’ and 5’- GTCGACCGGTAGCCACAACTTTTGC-3’ containing the restriction sites for NdeI and SalI (underlined). The PCR product was cloned into the pCR 2.1-TOPO TA vector and subcloned into the expression vector pET28a+. The recombinant construct TgPPase/pET28a was transformed into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIPL (Stratagene) and protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Recombinant TgPPase (rTgPPase) was purified with an His-Bind Quick 900 Cartridge following the manufacturer’s instructions. The eluted fractions were pooled and desalted using a HiTrap column.

Antibody Generation and Purification

The purified rTgPPase protein was sent to Cocalico Biologicals, Inc (Reamstown, PA) for production of guinea pig polyclonal antiserum. The antiserum was affinity purified with the cyanogen-bromide-activated resin [43].

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using standard protocols. Western blot analysis were performed as described [44] using an affinity purified anti-TgPPase polyclonal antibody (1:10,000) or anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:15,000).

Fluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluorescence assays were performed as described [44] by using as primary antibody the purified anti-TgPPase at 1:100 dilution. The secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor® 555-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (H+L) (1:1,000). Images were collected on an Olympus IX-71 inverted fluorescence microscope with a Photometrix-cooled CCD camera (CoolSnapHQ), and deconvolved for 15 cycles using SoftWarx deconvolution software (Applied Precision, Inc).

PPase Activity Measurement

rTgPPase activity was assayed by measuring the release of Pi using a published method [45]. The standard assay mixtures contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 3 mM MgCl2, 250 µM PPi and 1.36 ng of purified rTgPPase protein or 50 mM MES (pH 6.0), 3 mM CoCl2, 150 µM poly P3, or 50 mM MES (pH 6.5), 3 mM MnCl2, and 100 µM GP4, 100 µM ATP, or 100 µM poly P75 and 45 ng of rTgPPase. After a 10 min incubation at 37 °C, reactions were stopped by the addition of an equal volume of a mixture of 3 parts of 0.045% malachite green and 1 part of 4.2% ammonium molybdate [46]. The absorbance at 660 nm was measured with a SpectraMax M2e plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The specific activity of rTgPPase was defined as µmol Pi released min−1 mg−1 of protein. For determination of optimal pH conditions a 20 mM Tris/HEPES mixed buffering system was employed to ensure differences in activity were only due to pH and not ionic conditions. Inhibitor experiments were conducted at Km concentrations for both PPi and Poly P3.

To measure PPase activity in total cell lysates, purified tachyzoites were washed twice with buffer A plus glucose (BAG) (116 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Hepes, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.2), and resuspended in a small amount of the same buffer. The cells were broken by sonication in a Branson Sonifier 450 sonicator (10% amplitude, two 5 sec pulses).

The activity was also measured in subcellular fractions obtained after lysis of tachyzoites with silicon carbide as described before [24]. The homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min at 4 °C to obtain a supernatant and a pellet fractions. The enzymatic activity was measured as described above.

Extraction and Determination of PPi, ATP

PPi and ATP were extracted with ice-cold 0.5 M HClO4 (PCA) as described previously [24]. PPi measurements were done by measuring the amount of Pi released upon treatment with Thermostable Inorganic Pyrophosphatase (TIPP) (NEB). The reactions were performed in a 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 6 mM MgCl2, with 0.04 units/ml of inorganic pyrophosphatase. After 20 min incubation at 30 °C, the Pi released was measured with malachite green as described [45]. On the same PCA extraction, samples were used for the determination of short chain polyphosphate (poly P) by quantifying the amount of phosphate after treatment with S. cerevisiae polyphosphatase.

For the determination of cytosolic and organellar PPi, purified tachyzoites (4 – 8 × 108 cells) were washed once in an hyposmotic lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, 100 mM sucrose, 10 mM sodium fluoride) by centrifugation at 1,000×g. The pellet was subjected to three cycles of freezing and thawing using a dry ice-ethanol bath (5 min), and a 37°C water bath (1 min), resuspended in hyposmotic lysis buffer and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was taken as the cytosolic fraction and the pellet as the organellar fraction containing PPi stored predominantly in acidocalcisomes. Efficiency of this fractionation was assessed by testing for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, a cytosolic enzyme in T. gondii [47] and therefore should not be detected in the organellar fraction. LDH activity was monitored fluorometrically by using the LDH present in the experimental samples to oxidize NADH to NAD+ as the enzyme converted pyruvate (supplied in the reaction buffer) to lactate (excitation = 340 nm; emission = 460 nm). Both fractions were analyzed as described above for PPi and short chain poly P. The intracellular and organellar concentrations of PPi were calculated from the respective cell volume of 16.5 ± 3 µl for 109 cells [24] and assuming that PPi is mainly located in acidocalcisomes and these occupy 1% of the total cell volume. Acidocalcisome volume was estimated assuming a spherical shape with a diameter of 200 nm and an average of 10 acidocalcisomes per extracellular tachyzoite.

ATP was measured using an ATP determination kit (Molecular Probes, Catalog number A22066). For the calculation of the intracellular concentrations of ATP in tachyzoites a cell volume of 16.5 ± 3 µl for 109 cells was used [24].

Measurement of Proton Extrusion in Wild Type (RH) and TgPPase-OE Cells

Rates of proton extrusion were measured in RH and TgPPase-OE cells following basic procedures [48]. Freshly egressed tachyzoites were washed with BAG and split in two: cells further washed and suspended in the same buffer and cells further washed and suspended in the same buffer without glucose (BA). Both cell preparations were kept on ice at a concentration of 1×109 cells ml−1 until analysis. Proton extrusion was measured as described [48]. The fluorescence was measured by using a FL-4500 fluorescent spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Toyko, Japan). Calibration of fluorescent measurements to specific pH values was done as described [48].

Measurement of Intracellular pH in Wild Type (RH) and TgPPase-OE Cells

Loading of RH and TgPPase-OE cells with BCECF-AM for pH measurements was done as described previously [49]. Intracellular pH was measured in the SpectraMax M2e plate reader at excitation wavelengths of 505/440 nm and emission at 530 nm. The calibration of pH units to fluorescence ratio was as previously described [49, 50].

Measurement of Lactate Extrusion in Wild Type (RH) and TgPPase-OE Cells

Freshly egressed tachyzoites were washed three times with BAG and resuspended in the same buffer at a cell concentration of 5×108 cells ml−1. Reactions were terminated at different times (0–10 minutes) by spinning the cells down and removing the supernatant for analysis of the extruded lactate. This metabolite was quantified by the enzymatic conversion of lactate to pyruvate using lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, Sigma, L-2500) and measurement of the concomitant production of NADH. Enzymatic assay conditions were setup following published conditions [51, 52]. A 70 µl aliquot equivalent to 3.5 × 107 cells was added to 200 µl of reaction mix (600 mM glycine, 346 mM hydrazine, 17 mM EDTA, 15 mM NAD, 10 U ml−1 LDH; pH = 9.2) and fluorescence was monitored on the SpectraMax M2e plate reader for 20 min. NADH was measured using excitation and emission wavelengths of 340 nm and 460 nm, respectively. Fluorescent values were converted to units of lactate using a standard curve where known amounts of L-lactate were added to the reaction mix and NADH production was monitored.

RESULTS

Cloning the TgPPase Gene

The gene encoding a soluble PPase was identified by a BLAST search with the T. brucei soluble inorganic PPase sequence (NCBI GenBank protein accession number AAP74702). The T. gondii gene encodes for a protein of 381 amino acids (TgPPase) with a predicted molecular weight of 42 kDa. The TgPPase sequence has an overall identity with the yeast PPase (Y-PPase) of only 28%, but the 13 essential amino acids that form the active site structure of the Y-PPase (inferred from the crystal structure) are conserved [53] (Supplementary Fig. 1). Southern blot analysis was performed using a fragment covering the entire coding region of TgPPase as a probe, and showed only one band suggesting the presence of a single TgPPase gene in the T. gondii genome (Supplementary Fig. 2A). TgPPase transcript levels, as measured by RT-PCR, were similar for both tachyzoites and bradyzoites of the ME49 strain (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Phylogenetic Analysis of the TgPPase Gene

The TgPPase amino acid sequence (AAU88181) was used as a query to search for orthologs in the OrthoMCL database (version 2). Our phylogenetic analysis shows two main branches with high bootstrap support (100%/72%) when kinetoplastid inorganic PPases are used as outgroup (Fig. 1). The two groups are: (1) bacterial and bacterial-like plant soluble PPases, and (2) plant chloroplast and fungal/animal cytosolic and mitochondrial PPases (Fig. 1). In addition, our phylogenetic tree supports that the T. gondii enzyme is a type I inorganic PPase since it clusters with fungal/animal and plant chloroplast soluble inorganic PPases with high bootstrap confidence levels using both distance and parsimony methods (74%/74%) (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for the alignment of the sequences used for the tree in Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of type I inorganic pyrophosphatases.

The consensus phylogenetic tree was built from 100 replicates using the distance and parsimony methods as described in the “Experimental” section. Bootstrap values from 100 replicates are shown in bold and italics as obtained by the distance and parsimonius methods, respectively. The 0.2 bar represents amino acid substitutions per site. The sequence accession numbers as provided by GenBank are indicated in parentheses: Aquifex aeolicus VF5 (NP_214066.1), Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast PPase (At5g09650.1), A. thaliana (At1g01050.1), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii mitochondrial PPase (AJ298232), C. reinhardtii chloroplast PPase (AJ298231), Cryptosporidium parvum (cgd4_1400), Escherichia coli W3110 (NP_418647.1), Homo sapiens cytosolic PPase (ENSP00000317687), H. sapiens mitochondrial PPase (ENSP00000343885), Kluyveromyces lactis cyotosolic PPase (KLLA0E17721g), K. lactis mitochondrial PPase (KLLA0E11055g), Leishmania major putative mitochondrial PPase (LmjF03.0910), Mus musculus cytosolic PPase (ENSMUSP00000020286), M. musculus mitochondrial PPase (BAB22922), Nostoc sp. PCC7120 (P80562), Oriza sativa chloroplast PPase (3698.m00155), O. sativa (12001.m13461), Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 (PFC0710w), Rhodospirillum rubrum (AF115341_1), Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytosolic PPase (YBR011C), S. cerevisiae mitochondrial PPase (YMR267W), Solanum tuberosum (CAA12415), Synechocystis PCC6803 (P80507), Thermoplasma acidophilum (P37981), Thermus thermophilus (BAA24521), Toxoplasma gondii (AAU88181), Trypanosoma brucei putative mitochondrial PPase (Tb927.3.2840/Tb03.27C5.190), T. cruzi putative mitochondrial PPase (Tc00.1047053508181.140) and Zea mays (O48556). MIT, mitochondrial, CYT, cytosolic, CHL, chloroplastic.

Expression, Purification, and Biochemical Characterization of TgPPase

The expression of TgPPase and purification by affinity chromatography produced a single protein band (Supplementary Fig. 2C). The purified protein was characterized biochemically.

The enzymatic activity of the rTgPPase showed an absolute requirement for divalent cation cofactors with Mg2+ being the most efficient at a concentration of 1 mM (238.17 ± 6.51 µmol Pi min−1 (mg protein)−1). The optimum pH for the hydrolysis of PPi was 8.5 (Fig. 2A). At this pH, other cations such as cobalt, zinc, calcium, and manganese, marginally stimulated the activity over basal levels (Fig. 2C). The enzyme was also able to hydrolyze tripolyphosphate (poly P3) although with lower efficiency (Table 1). For this polyphosphatase activity the preferred cofactor was Co2+ (Figs. 2B and 2D), as occurs with the Y-PPase [13, 16], and the optimum pH range was 6 to 6.5. The enzyme had low hydrolyzing activity of long chain poly P (poly P75), ATP and guanosine tetraphosphate (GP4) in the presence of Mn2+ as the divalent cation cofactor (Supplementary Fig. 4A,C).

Figure 2. Enzymatic characterization of the rTgPPase.

PPase activity was determined as described under “Experimental” using 23 µM PPi (A, C), or 9 µM poly P3 (B, D). A, B Optimun pH measurements with PPi (A) or Poly P3 (B) as substrate. A 20mM Tris/HEPES mixed buffering system was used to manipulate the pH of the reaction buffer. C, D, Optimun cation concentrations measurements with PPi (C) or Poly P3 (D) as substrate. Results are expressed as % of maximum activity taken as 100%. Where indicated, 5 mM EDTA was used. E,F, enzymatic activity measured with different concentracions of PPi (E) or PolyP3 (F). These experiments were done using 3.0 mM MgCl2, (E), or 3 mM CoCl2 (F). Insets represent the linear transformation, by double reciprocal plot, of each curve. Experiments were repeated three times, each one in triplicate, with similar results.

Table I.

Kinetic parameters of rTgPPase with different substrates.

| Substrates | pH | cation |

Vmax* (µmole/min/mg) |

Km* (µM) |

kcat (min−1) |

kcat/Km (min−1 · M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPi | 8.5 | Mg2+ | 264.45 ± 8.33 | 23.10 ± 0.03 | 194.40 | 8.42 × 106 |

| Poly P3 | 6.0 | Co2+ | 6.41 ± 0.25 | 9.01 ± 1.21 | 0.14 | 1.57 × 104 |

| Poly P75 | 6.5 | Mn2+ | 6.16 ± 0.18 | 6.57 ± 0.95 | 0.28 | 4.31 × 104 |

| ATP | 6.5 | Mn2+ | 5.27 ± 0.23 | 51.42 ± 6.89 | 0.24 | 4.71 × 103 |

| GP4 | 6.5 | Mn2+ | 5.22 ± 0.40 | 98.66 ± 19.55 | 0.24 | 2.43 × 103 |

The Km and Vmax were calculated using SigmaPlot 10.0.

Table 1, Figs. 2E,F, and Supplementary Fig. 4B,D show the kinetic properties of the enzyme for the hydrolysis of PPi, poly P3, poly P75, ATP and GP4. At the optimal conditions, it is clear that the catalytic efficiency for the hydrolysis of PPi (measured as kcat/Km) is significantly higher than for the hydrolysis of the other substrates.

Inhibition of the rTgPPase

Aminomethylenediphosphonate (AMDP), a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar proton PPase did not show any effect on the activity of this enzyme at a concentration of 40 µM (data not shown). However, sodium fluoride (NaF), a known inhibitor of soluble PPases, inhibited the enzyme with an IC50 of 223 ± 31.8 µM (Supplementary Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table 1). Poly P3 hydrolytic activity was also significantly inhibited by fluoride (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Sodium molybdate caused minor inhibition of pyrophosphate hydrolysis (maximum inhibition = 27%, Supplementary Fig. 5B). The small amount of activity for poly P3 hydrolysis was effectively inhibited by sodium molybdate, a general phosphatase inhibitor. Imidodiphosphate (IDP) (40 µM), a bisphosphonate derivative, did not have any effect on the activity of rTgPPase (data not shown).

Subcellular Localization of TgPPase

To investigate the localization of TgPPase, we performed indirect immunofluorescence analysis (IFA) in tachyzoites expressing cytosolic YFP using antibodies against the TgPPase enzyme. As evidenced by the colocalization with YPF, the endogenous localization of the TgPPase enzyme was determined to be the cytosol in tachyzoites of T. gondii (Fig 3A). Western blot analysis of cytosolic and membrane fractions of tachyzoites confirmed the cytosolic localization of the protein (Fig. 3B). Both the specific activity and the total activity of the enzyme were higher in the soluble fractions (Figs. 3C and 3D).

Figure 3. The TgPPase localizes to the cytosol of RH, wild type T. gondii tachyzoites.

RH (wildtype) tachyzoites expressing YFP were used [30] to test for colocalization of endogenous expression of TgPPase. (A) TgPPase localized to the cytosoplasm of RH tachyzoites. Parasites were fixed and stained with an anti-TgPPase antibody (1:100) or observed by direct YFP fluorescence where indicated. The overlay images show co-localization of both proteins in the cytosol. Scale bars = 5 µm. (B) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions of T. gondii tachyzoites. Equal protein amounts (5 µg) from supernatant (“S”) and pellet (“P”) fractions were loaded. The molecular mass standards (in kDa) are shown on the left. (C, D) Specific and total enzymatic activity, respectively, in supernatant (“S”) and pellet (“P”) fractions after centrifugation of lysates at 100,000×g for 1 h. Other experimental details are described under “Experimental”.

Effect of Overexpression of TgPPase on Cell Growth and Metabolism

A clone of T. gondii tachyzoites was isolated after limited dilution of cells transfected with the pTubTgPPase-flag/ sagCAT plasmid and selection with chloramphenicol. These cells showed significantly higher levels of TgPPase protein (Fig. 4A) and enzymatic activity (Fig. 4B; P < 0.05). Further IFA localization studies with cytosolic YFP determined that the TgPPase protein in OE mutants maintained a cytosolic localization (data not shown). Rates of growth in overexpressing mutants (hereafter referred to as ‘OE mutants’) using uracil incorporation were found to be significantly lower (P < 0.05) when compared to the growth rate of RH, wild type parasites (hereafter referred to as ‘RH’) (Fig. 4C). The lower growth rates were confirmed using plaque assays to measure growth/invasion efficiency in wild type and over expressing mutants (Fig. 4D-F). OE mutants had significantly lower plaque numbers (P < 0.001) as well as lower relative size of plaque forming units (P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Cells overexpressing TgPPase show higher levels of TgPPase protein and activity but grow at a slower rate.

A, Western blot analysis. RH cells; OE, cells transfected with the expression vector ptubTgPPase-flag/sagCAT and selected with chloramphenicol as indicated under “Experimental” (TgPPase-OE cells). The blot was sequentially probed with anti-TgPPase antibody (upper panel) and anti-α-tubulin antibody as loading control (bottom panel). B, PPase activity of crude cell lysates obtained as described under “Experimental”. AMDP, a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar proton PPase (V-H+-PPase) at 40 µM, was added to the lysate. C, OE mutant tachyzoites had significantly lower [3H]-uracil incorporation than wild-type cells after 24 h inoculation of hTERT host cells. The results are representative of three independent experiments, each one performed in triplicate. The bars are the means ± S.D. Asterisks (*) show P values < 0.05, determined by the Student’s t-test. D-F, Plaque assays comparing growth and invasion ability of wild type cells (RH) and TgPPase over expressing mutants (OE). D, Determination of plaque forming units in a monolayer of hTERT host cells. 200 parasites were incubated in each well for 9 days, washed away and remaining host cells were stained to determine the number of zones cleared of host cell due to parasite invasion and replication (i.e., plaques). Values shown are averages (± SE), N = 6. E, Determination of relative area of plaques. Data taken from same experiments as shown in panel D. Area represents the percent of the total available area that the average plaque occupied. Singe factor ANOVA (df = 1, 11) showed significantly lower plaque numbers and plaque area in OE mutant cells. * = P < 0.05; *** = P < 0.001. F, Representative wells used to determine plaquing efficiency for RH and TgPPase OE mutant parasites.

To understand the possible consequences of elevated pyrophosphatase activity in OE mutants we investigated the cellular amounts of phosphate-related molecules. Cellular levels of PPi were 40% lower than in wild type RH cells (Fig. 5A; P < 0.01). Cellular concentrations of short-chain poly P between OE mutants and RH cells were similar at about 5 mM in phosphate equivalents (Fig. 5B). Under identical conditions as above, cellular concentrations of ATP were significantly elevated (P < 0.05) by 75% in extracellular tachyzoites over-expressing TgPPase (Fig. 5C). However, under conditions in which no glucose was present, the difference in ATP concentration was abolished.

Figure 5. T. gondii parasites overexpressing TgPPase (OE) contain lower PPi and higher ATP levels.

A, Over-expression of TgPPase leads to a significant reduction in total PPi levels as compared with wild-type RH tachyzoites (ANOVA, df = 1,16; P < 0.01). Bars represent the average (± SE) of 9 quantifications for each cell type. B, No difference in short chain poly P levels between wild type RH and OE mutants for TgPPase. Bars represent the average of 9 determinations for each cell type. Values are in phosphate equivalents of hydrolyzed short chain poly P groups. C, Over-expression of TgPPase leads to an increase in the intracellular levels of ATP in the presence of glucose. Newly released tachyzoites were filtered and washed twice with BAG with or without glucose and incubated in the same buffer for 1 hour. ATP was extracted and measured as described under “Experimental”. The results are representative of three independent experiments, each one performed in triplicate. The bars are the means ± S.D. Asterisks (*) show P values < 0.05, determined by the Student’s t-test.

In order to rule out the possibility that the PPase OE phenotype was only a consequence of genetic manipulation and therefore non-specific in nature, we measured cellular pyrophosphate concentration and growth in mutant parasites expressing an unrelated gene, the fluorescent tomato protein (hereafter referred to as Tomato OE mutants). The Tomato OE mutants were derived from the same genetic background as the PPase OE mutants and underwent similar genetic manipulation. Cellular pyrophosphate concentration in the Tomato OE parasites was similar to that measured in RH, wildtype parasites (Supplementary Fig. 6A). Likewise, growth rates in these unrelated expression mutants were similar to those of RH, wild type parasites as measured by plaque assays (Supplementary Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the phenotype observed in the PPase OE mutants is not an artifact from genetic manipulation and bolster the relationship between pyrophosphate concentration and ATP and growth.

Since most PPi in T. gondii is localized in acidocalcisomes [24] we investigated whether cytosolic or organellar PPi was affected in cells over-expressing the pyrophosphatase. By lysis of the plasma membrane by freeze-thaw cycling in a hypotonic buffer, the distribution of PPi in the cytosolic and organellar fractions of extracellular tachyzoites was determined. In order to determine the concentration of PPi in these fractions we assumed that the cellular volume and the size and number of acidocalcisomes in the OE mutants were similar to that of wild type parasites (i.e., 1×109 parasites = 16.5ul and acidocalcisomes occupy 1% of the cellular volume). This assumption was confirmed in our microscopic analyses and in our indirect immunofluorescence assays examining acidocalcisome markers (e.g., TgVP1, data not shown). The majority of PPi was found in the organellar fraction (Fig. 6B, ~ 360 mM). A significant difference, however, was observed in the soluble fraction (Fig. 6A). RH cells had more than 6-times the concentration of PPi than OE mutants (0.55 and 0.09 mM, respectively; P < 0.01). The efficiency of this fractionation was verified by measuring LDH activity in both the supernatant (i.e., cytosol) and the pellet (i.e., organellar) fractions. Over 95% of measured LDH activity was found in the cytosolic fraction (Supplementary Fig. 6). In conjunction with the PPi distribution, these results demonstrate effective lysis of the plasma membrane without significant disruption of organelles containing pyrophosphate (i.e., acidocalcisomes). These results indicate that the total cellular differences in PPi are a result of different concentrations of PPi in the cytosol, which is in agreement with the cellular location of the TgPPase enzyme (Fig. 3).

Figure 6. PPi content of cytosolic and acidocalcisome fractions.

PPi was determined in cytosol (A) and 17,000G pellet (acidocalcisome) fractions obtained as described under “Experimental” from wild type (RH) and TgPPase-OE parasites (OE). Bars represent average concentration (± SE) of 3 quantifications for each cell type. Where no error bars are present the bars fall within the graphical representation of the average value. Concentration was determined by dividing the total nmol PPI in the cytosolic and organellar fractions by their respective estimated volumes as described under “Experimental”. *Cytosolic PPi concentration was significantly lower in OE mutants (ANOVA, df = 1, 4; P < 0.01).

Metabolic Changes in TgPPase-OE Cells as Measured by Proton Extrusion, Lactic Acid Release and Intracellular pH

T. gondii is known to preferentially metabolize glucose to lactic and acetic acids and excrete them to the medium, accompanied by protons [54]. The large, glucose-dependent differences observed in ATP concentration in conjunction with the cytosolic differences in PPi concentration between RH and OE mutant parasites prompted us to investigate the glycolytic flux of extracellular tachyzoites. Proton extrusion and lactate extrusion were measured in extracellular tachyzoites in the presence and absence of glucose. In cells that rely on glycolysis for energy production, these processes have been shown to be reliable metrics of glycolytic flux [55–57].

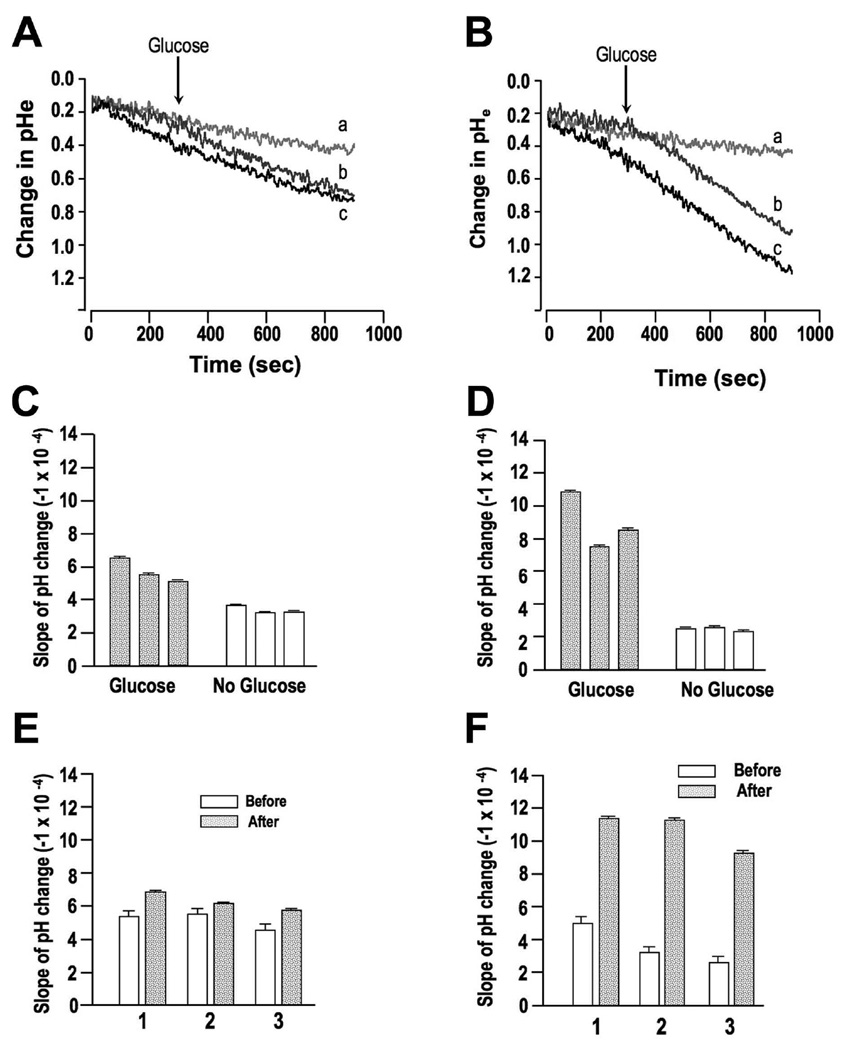

To investigate whether the increase in ATP levels resulted as a consequence of an increased glycolytic rate, proton extrusion was measured in RH parasites and OE mutants using the free acid form of BCECF and quantifying the rate at which the pH of the extracellular media (pHe) changed. Proton extrusion was measured in RH (Fig. 7A, C, and E) and OE mutants (Fig. 7B, D, and F) in the presence of glucose (5 mM) and compared to cells deprived of glucose for ~ 2 h (Figs. 7A and C (RH cells); (Figs. 7B and D) (OE mutants). Furthermore, 5 mM glucose was added to the cells deprived of glucose during the proton extrusion measurement to evaluate the immediate response in cellular metabolism [Fig. 7A, trace b and 7E (RH); Fig. 7B, trace b and 7F (OE mutants)]. RH cells showed a small, but significant increase (ANOVA; df = 1,11; P < 0.01) in proton extrusion when glucose was present (Fig. 7A, trace c) or when added during the experimental incubation time (Fig. 7A, trace b and c) relative to rates when cells were glucosedeprived (Fig. 7A, trace a). Proton extrusion rates in OE mutants exhibited a greater sensitivity to the presence or absence of glucose. In the absence of glucose, (Fig. 7B, trace a) rates of proton extrusion in OE mutants were slightly lower, though statistically similar to rates in glucosedeprived RH cells (average glucose-deprived rates were −4.3×10−4 and −3.1×10−4 pHe units s−1 for RH and OE cells, respectively). When glucose was present in the experimental buffer, rates of proton extrusion in OE cells exhibited a significant, 3.2-fold increase (ANOVA, df = 1,11; P < 0.001) from −3.1×10−4 to −9.8×10−4 pHe units s−1 (Fig. 7B, traces b and c). Average rates of proton extrusion while glucose was present were significantly higher (ANOVA, df = 1,11; P < 0.001) in OE cells by 1.6-fold, relative to RH cells (−9.8×10−4 and −6.0×10−4 pHe units s−1 for TgPPase-OE and RH cells, respectively) (compare Figs. 7D and 7F with 7C and 7E, gray columns). Despite the large differences in proton extrusion, there was no significant difference in intracellular pH (pHi) between RH parasites and OE mutants (ANOVA, df = 1,5; P > 0.05, data not shown). The average pHi was 7.18 and 7.23 for RH and OE cells, respectively. Rates of proton extrusion in the unrelated Tomato OE mutants were similar to those of wild type parasites (Supplementary Fig. 8A-D), providing further support for the relationship between cellular pyrophosphate concentration and glycolytic flux in T. gondii.

Figure 7. Proton extrusion by wild type (RH) and TgPPase-OE (OE) parasites.

Rates of proton extrusion were measured using the free acid form of BCECF. A, C, and E, summary of proton extrusion in RH cells. B, D, and F, summary of proton extrusion in OE mutant cells. A, representative tracings depicting changes in extracellular pH (pHe) in RH tachyzoites in the presence of 5 mM glucose (black, trace c), no glucose (light gray, trace a), and in cells where 5 mM glucose was added 300 seconds into recording (dark gray, trace b). B, same tracing as in A using OE mutants. C, resultant slope values (change in pHe per second) in the presence (gray bars) or absence of glucose (open bars) for proton extrusion in RH cells using data represented in tracings ‘a’ and ‘c’ in panel A. D, resultant slope values (change in pHe per second) in the presence (gray bars) or absence of glucose (open bars) for proton extrusion in OE mutant cells using data represented in tracings ‘a’ and ‘c’ in panel B. E, rate of pHe change before (open bars) and after (gray bars) addition of 5 mM glucose to media in RH cells using data represented in tracing ‘b’ in panel A. F, rate of pHe change before (open bars) and after (gray bars) addition of 5 mM glucose to media in OE mutant cells using data represented in tracing ‘b’ in panel B. All estimates shown in panels C-F were determined from three independent experiments and error bars represent the standard error of the slope.

To better assess the link between pyrophosphate and glycolytic flux, rates of lactate extrusion were measured in RH and soluble pyrophosphatase OE mutants as an independent verification of the rate of glycolysis. Rates of lactate extrusion were measured in RH cells and OE mutant cells in which glucose had been added to the experimental buffer (5 mM). Duplicate measurements of the amount of lactate extruded to the extracellular medium over the course of 10 min (measurements made at 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min) showed a significant linear increase with time for both cells types (Fig. 8). The lactate extrusion rate for RH cells was 1.07 ± 0.03 (SE) fmol h−1 cell−1 and for the OE cells (Fig. 8, inset) 1.90 ± 0.04 (SE) fmol h−1 cell−1 (ANOVA: df = 1,18; P < 0.001). The difference in lactate extrusion between RH and OE cells was 1.8-fold, a value similar to the difference in proton extrusion rates for both cell types (1.6-fold, see above).

Figure 8. Lactate extrusion in wild type (RH) and TgPPase-OE (OE) parasites.

Lactate extrusion rates were measured using an enzyme-coupled reaction (LDH) fluorescently monitoring the production of NADH as lactate is converted to pyruvate. Lactate extrusion was monitored in RH (open circles) and OE mutant (gray circles) tachyzoites with duplicate samples taken at 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 minutes for each cell type. Regression analysis was performed on each cell type and the resultant slope, depicting the rate of lactate extrusion, is shown in the inset as the cell-specific rate of lactate extrusion. Error bars are the standard error of the slope. * P < 0.001; ANOVA comparison of slopes between RH and TgPPase-OE cells (df = 1,18; F value = 253).

The difference in the proton and lactate extrusion rates between RH and the OE cells might be due to an inhibitory effect of PPi on the glycolytic pathway. The T. gondii pyruvate kinase (PK) is an allosteric enzyme and is activated by glucose-6-P [58]. We investigated if PPi could be inhibiting this enzyme by measuring its activity in a T. gondii lysate in the presence of varying PPi concentrations. For the range of PPi concentrations we measured in the cytosol (i.e. up to 1 mM), we found no detectable inhibition of pyruvate kinase (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The goals of this study were to characterize the enzyme that directly regulates cytosolic levels of pyrophosphate in the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii and employ its expression as a means to manipulate cytosolic pyrophosphate concentrations in this medically relevant parasite. Bioinformatic searching (e.g., blast searching and querying Toxodb.org) for soluble pyrophosphatases yielded TgPPase as the only soluble pyrophosphatase found in the T. gondii genome. Pyrophosphate is both an important substrate and product for several metabolic reactions and its generation in the cytosol is highly regulated so as to avoid a build-up of toxic concentrations. For these reasons we chose to use the over-expression of TgPPase as a means to manipulate the cytosolic concentration of pyrophosphate. It was our expectation that given the placement of PPi in so many key metabolic reactions, its manipulation would have far-reaching consequences on the metabolism of T. gondii tachyzoites.

The alignment of the TgPPase gene sequence shows conservation of amino acids present in other PPases. Considering its phylogenetic position, its Mg2+ requirement and its fluoride sensitivity the TgPPase belongs to the family I PPases. Phylogenetic analysis shows that apicomplexan PPases cluster with the sequences belonging to mitochondria and chloroplasts, suggesting a proteobacterial origin. The cytosolic localization of TgPPase could be due to specific requirements of this enzyme in T. gondii. One hypothesis could be that the TgPPase gene was acquired through horizontal gene transfer, a mechanism that has been shown to occur in apicomplexan parasites [59–62]. Since the kinetoplastid PPases are highly divergent but still related to other type I inorganic PPases, we selected them as outgroup (Fig. 1). In a study by Gómez-García et al [63], the Leishmania major inorganic PPase was suggested to be an ancestral type I eukaryotic soluble PPase with a calcium-dependent activity.

The catalytic efficiency of the purified recombinant TgPPase enzyme, as shown by the kcat/Km values in Table 1, indicates that the enzyme is highly efficient when hydrolyzing PPi. The enzyme is also able to hydrolyze poly P3, poly P75, ATP and GP4 with lower efficiency (Table 1). It is surprising that the recombinant enzyme shows an optimum pH of 8.5 and at the same time is cytosolic (Fig. 3). On analyzing Fig. 2A it can be observed that the activity is still high at cytosolic pHs 7.1–7.4. The enzyme preference for Mg2+, when hydrolyzing PPi, and for other non-physiological cations such as Co2+ or Mn2+, when hydrolyzing other substrates, is similar to what has been found for the Y-PPase [16].

Given that the phylogenetic analysis and biochemical characterization fully supported the identity of TgPPase as a Type I pyrophosphatase with a high specificity for PPi and only much lower affinities for alternate substrates, we employed the over-expression of this enzyme as a means to decrease the cytosolic concentration of PPi. Over-expression successfully increased the production of TgPPase protein as well as its activity. This increased activity was still maintained in the cytosol of OE mutants, as measured by fractionation experiments and indirect immunofluorescence assays. In conjunction with this, we observed a significant decrease in the substrate of TgPPase, PPi, which was localized to the cytosol of OE mutants. These results confirm that the over-expression of TgPPase is a reliable tool for understanding the metabolic significance of pyrophosphate.

The phenotype of the T. gondii clone over-expressing TgPPase (OE mutant) was somewhat unexpected. Relative to the wild type parasites, OE mutants had higher levels of ATP. T. gondii tachyzoites rely on glycolysis for energy production [64, 65]. Unlike glycolysis in mammalian cells, T. gondii possesses a phosphofructokinase (PFK) that utilizes PPi to drive the rate-limiting conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate [28]. Our initial expectation was that the decrease in cellular PPi concentration would cause a decrease in glycolysis since a key energetic substrate had been significantly reduced. Measurements of ATP concentration showed that, contrary to this expectation; energy metabolism had increased in the OE mutants. To ensure the increase in ATP was a specific outcome of increased energy metabolism, we measured rates of glycolytic flux.

TgPPase OE mutants displayed a significant increase in glycolysis, as measured by both proton and lactate extrusion from extracellular tachyzoites. Rates of proton and lactate extrusion have been shown to be tightly linked to glycolytic flux in a wide range of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, including bacteria [56, 66], yeast [67], and human platelet cells [55]. T. gondii, like other apicomplexans, obtains most of its energy through glycolysis [64][65] with lactate representing a dominant end product of glycolysis [54, 68] Recently, Lin et al. [65] used lactate extrusion to measure glycolysis in extracellular tachzyiotes of T. gondii. These reasons compelled us to use rates of proton and lactate extrusion as metrics of glycolytic flux for direct comparison between RH parasites and OE mutants. Both cell types responded to the addition of 5 mM glucose with increased rates of proton extrusion. However, the rate of extrusion was ~ 60% higher in OE mutants when in the presence of glucose. Similarly, rates of lactate extrusion in the presence of 5 mM glucose were significantly higher (~80%) in the OE mutants. The high sensitivity and immediate response to the addition of glucose in both cell types is not surprising given that the localization of glycolytic enzymes in extracellular tachyzoites is at the pellicle region just below the plasma membrane [47]. This stimulation in glycolytic flux resulted in a quantitatively similar increase in ATP concentration in the OE mutants (i.e., ATP concentration increased by 75%). To show that these phenotypic traits observed in the TgPPase OE mutants are specific to the reduction in PPi, we compared our results from wild type, RH and TgPPase OE mutants with a completely unrelated expression mutant. Genetically modified parasites expressing the fluorescent tomato protein had similar levels of pyrophosphate to RH and likewise similar rates of growth and glycolysis (as measured by proton extrusion).

The regulatory mechanism by which cytosolic concentrations of PPi can be related to higher glycolytic flux in T. gondii still remains undetermined. Regulation of glycolysis has been studied in several organisms from bacteria to higher eukaryotes. It has been demonstrated in other cell types that PPi inhibits several glycolytic enzymes, such as hexokinase in Trypanosoma brucei [69] and phoesphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxykinase in T. cruzi [70]. In animal cells PPi, either directly administered or produced intracellularly by activation of short chain fatty acids, produces effects that mimic glucagon injection in that liver glucose is increased, and there is a change in 3- phosphoglycerate/pyruvate ratio, suggestive of PK inhibition [4]. Three enzymes that typically are observed to be critical regulators of glycolytic flux are: hexokinase, phosphofructokinase (PFK), and pyruvate kinase (PK). In T. gondii, however, very little is known about regulation of glycolysis [71]. T. gondii possesses one annotated hexokinase, but it does not use PPi as a substrate and is not inhibited by it either [71]. Our current analysis of pyruvate kinase (PK) in T. gondii wild-type and TgPPase over-expressing cells found no significant difference in PK activity for the range of PPi differences between the two cell types.

As previously mentioned, T. gondii tachyzoites possess a plant-like phosphofructokinase that uses PPi as the high-energy phosphoryl donor rather than ATP (PPi-PFK). Therefore a decrease in PPi would be expected to result in a corresponding decrease in the rate-limiting conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate by PPi-PFK. However, the Km for PPi of PPi- PFK is 33 µM [28]. The cytosolic concentrations of both wild type and OE mutants may be high enough (550 and 90 µM, respectively) to result in only minimal differences in PPi-PFK activity. An alternative explanation that has been proposed in plant cells [72] is that the increase in orthophosphate (Pi) from the breakdown of PPi results in activation of fructose-6-phosphate-2 kinase, the product of which is fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F-2,6-BP), a strong activator of PPi- PFK [72]. However, unlike plant cells, the PPi-PFK of T. gondii does not appear to be activated by F-2,6-BP [28].

The up-regulation of glycolysis and increase in ATP levels due to decreases in cytosolic PPi has also been observed in plant cells [72, 73]. In developing tubers of potato, cytosolic overexpression of pyrophosphatase causes a decrease in cytosolic PPi as well as an unexpected increase in sucrose degradation and subsequent increases in glycolysis and starch production [73]. The up-regulation of these pathways is thought to be due to the PPi-dependent sucrose degradation pathway and downstream activation of starch synthesis. The cytosol of T. gondii possesses crystalline, water-soluble polysaccharide particles called amylopectin granules, which are similar to those of plant starch [74]. While these granules are typically associated with the bradyzoite and sporozoite stages, it has been shown that media acidification in tachyzoites can cause a significant increase in the presence of amylopectin granules [74]. The increase we observe in glycolysis and the concomitant proton extrusion may be related to the activation of amylopectin synthesis and therefore analogous to stimulation of starch synthesis seen in plant cells. In addition, this effect could lead to the observed decrease in uracil incorporation and plaque formation, demonstrating a decrease in growth rates in over expressing parasites.

It is a widely held concept that soluble PPases play an important metabolic role by driving reactions such as protein, RNA, and DNA synthesis to completion [1] and that the PPi produced in anabolic reactions is instantly hydrolyzed. However, a potential role of PPi as a regulator of metabolic processes has also been proposed [4]. Our results support this assertion. Our findings highlight the regulatory role of PPi on a critical metabolic pathway of T. gondii. The regulatory role of PPi requires further study. Metabolomic analysis in conjunction with the use of these over-expressing mutants to vary cytosolic concentration of PPi should provide insight into further downstream consequences resulting from varying cytosolic PPi. Such analysis may have far reaching implications for the role of PPi in metabolic regulation in a variety of cell types.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Boris Striepen (UGA) for transgenic fluorescent T. gondii tachyzoites and the ptubYFP-YFP/sagCAT expression vector, William Sullivan (Indiana University School of Medicine) for the pTubP30-GFP-flag/sagCAT expression vector, and Takashi Asai for useful discussions. Nhu-y Nguyen provided assistance in proton extrusion measurements as part of an undergraduate research project. Cuiying Jiang and Allysa Smith provided excellent technical help.

Funding. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant AI-079625 to S.N.J.M. D.A.P. was partially supported by an NIH T32 training grant AI-60546 to the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases. R.C. was supported in part by NIH research supplement 3R01AI068647-04S1.

Abbreviations Used

- AMDP

aminomethylenediphosphonate

- BCECF

2’,7’-bis(2-carboxyethyl)- 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorscein

- GP4

guanosine tetraphosphate

- IDP

imidodiphosphate

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MES

4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- ORF

open reading frame

- poly P

polyphosphate

- poly P3

tripolyphosphate

- PPase

pyrophosphatase

- PPi

inorganic pyrophosphate

- PK

pyruvate kinase

- TgPPase

soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase 1 of T. gondii

- TgPPase-OE

TgPPase overexpressing cells

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Kornberg A. On the metabolic significance of phosphorolytic and pyrophosphorolytic reactions. In: Kasha HaPB., editor. Horizons in Biochemistry. New York: Academic Press, Inc.; 1962. pp. 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansurova SE. Inorganic pyrophosphate in mitochondrial metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;977:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lahti R. Microbial inorganic pyrophosphatases. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:169–178. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.2.169-178.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veech RL, Cook GA, King MT. Relationship of free cytoplasmic pyrophosphate to liver glucose content and total pyrophosphate to cytoplasmic phosphorylation potential. FEBS Lett. 1980;117(Suppl):K65–K72. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltscheffsky M, Schultz A, Baltscheffsky H. H+ -PPases: a tightly membrane-bound family. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)90617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeshima M. Vacuolar H(+)-pyrophosphatase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:37–51. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drozdowicz YM, Rea PA. Vacuolar H(+) pyrophosphatases: from the evolutionary backwaters into the mainstream. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:206–211. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01923-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott DA, de Souza W, Benchimol M, Zhong L, Lu HG, Moreno SN, Docampo R. Presence of a plant-like proton-pumping pyrophosphatase in acidocalcisomes of Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22151–22158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tammenkoski M, Benini S, Magretova NN, Baykov AA, Lahti R. An unusual, His-dependent family I pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41819–41826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tammenkoski M, Moiseev VM, Lahti M, Ugochukwu E, Brondijk TH, White SA, Lahti R, Baykov AA. Kinetic and mutational analyses of the major cytosolic exopolyphosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9302–9311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young TW, Kuhn NJ, Wadeson A, Ward S, Burges D, Cooke GD. Bacillus subtilis ORF yybQ encodes a manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase with distinctive properties: the first of a new class of soluble pyrophosphatase? Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 9):2563–2571. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oksanen E, Ahonen AK, Tuominen H, Tuominen V, Lahti R, Goldman A, Heikinheimo P. A complete structural description of the catalytic cycle of yeast pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1228–1239. doi: 10.1021/bi0619977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohne WE, Heitmann P. Tripolyphosphate as a substrate of the inorganic pyrophosphatase from baker's yeast; the role of divalent metal ions. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1974;33:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josse J. Constitutive inorganic pyrophosphatase of Escherichia coli. 1. Purification and catalytic properties. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:1938–1947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josse J. Constitutive inorganic pyrophosphatase of Escherichia coli. II. Nature and binding of active substrate and the role of magnesium. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:1948–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zyryanov AB, Shestakov AS, Lahti R, Baykov AA. Mechanism by which metal cofactors control substrate specificity in pyrophosphatase. Biochem J. 2002;367:901–906. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlesinger MJ, Coon MJ. Hydrolysis of nucleoside diand triphosphates by crystalline preparations of yeast inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960;41:30–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunitz M. An improved method for isolation of crystalline pyrophosphatase from baker's yeast. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;92:270–272. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno B, Bailey BN, Luo S, Martin MB, Kuhlenschmidt M, Moreno SN, Docampo R, Oldfield E. (31)P NMR of apicomplexans and the effects of risedronate on Cryptosporidium parvum growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:632–637. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno SN, Zhong L. Acidocalcisomes in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Biochem J. 1996;313(Pt 2):655–659. doi: 10.1042/bj3130655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigues CO, Scott DA, Bailey BN, De Souza W, Benchimol M, Moreno B, Urbina JA, Oldfield E, Moreno SN. Vacuolar proton pyrophosphatase activity and pyrophosphate (PPi) in Toxoplasma gondii as possible chemotherapeutic targets. Biochem J. 2000;349(Pt 3):737–745. doi: 10.1042/bj3490737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miranda K, de Souza W, Plattner H, Hentschel J, Kawazoe U, Fang J, Moreno SN. Acidocalcisomes in Apicomplexan parasites. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docampo R, de Souza W, Miranda K, Rohloff P, Moreno SN. Acidocalcisomes - conserved from bacteria to man. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:251–261. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigues CO, Ruiz FA, Rohloff P, Scott DA, Moreno SN. Characterization of isolated acidocalcisomes from Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites reveals a novel pool of hydrolyzable polyphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48650–48656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urbina JA, Moreno B, Vierkotter S, Oldfield E, Payares G, Sanoja C, Bailey BN, Yan W, Scott DA, Moreno SN, Docampo R. Trypanosoma cruzi contains major pyrophosphate stores, and its growth in vitro and in vivo is blocked by pyrophosphate analogs. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33609–33615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendoza M, Mijares A, Rojas H, Rodriguez JP, Urbina JA, DiPolo R. Physiological and morphological evidences for the presence acidocalcisomes in Trypanosoma evansi: single cell fluorescence and 31P NMR studies. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;125:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drozdowicz YM, Shaw M, Nishi M, Striepen B, Liwinski HA, Roos DS, Rea PA. Isolation and characterization of TgVP1, a type I vacuolar H+-translocating pyrophosphatase from Toxoplasma gondii. The dynamics of its subcellular localization and the cellular effects of a diphosphonate inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1075–1085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng ZY, Mansour TE. Purification and properties of a pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinase from Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90114-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo S, Vieira M, Graves J, Zhong L, Moreno SN. A plasma membrane-type Ca(2+)-ATPase co-localizes with a vacuolar H(+)-pyrophosphatase to acidocalcisomes of Toxoplasma gondii. EMBO J. 2001;20:55–64. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gubbels MJ, Li C, Striepen B. High-throughput growth assay for Toxoplasma gondii using yellow fluorescent protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:309–316. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.309-316.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfefferkorn ER, Pfefferkorn LC. Specific labeling of intracellular Toxoplasma gondii with uracil. J Protozool. 1977;24:449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1977.tb04774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin MB, Grimley JS, Lewis JC, Heath HT, Bailey BN, Kendrick H, Yardley V, Caldera A, Lira R, Urbina JA, Moreno SNJ, Docampo R, Croft SL, Oldfield E. Bisphosphonates Inhibit the Growth of Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania donovani, Toxoplasma gondii, and Plasmodium falciparum: A Potential Route to Chemotherapy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;44:909–916. doi: 10.1021/jm0002578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roos DS, Donald RG, Morrissette NS, Moulton AL. Molecular tools for genetic dissection of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;45:27–63. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61845-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholas KB, Nicholas HB, Deerfield DW. GeneDoc: Analysis and Visualization of genetic variation. EMBNEW.NEWS. 1997;4:14. ed.)^eds.) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Interactive analysis of phylogeny and character evolution using the computer program MacClade. Folia Primatol (Basel) 1989;53:190–202. doi: 10.1159/000156416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Efron B, Halloran E, Holmes S. Bootstrap confidence levels for phylogenetic trees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7085–7090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eck RV, Dayhoff MO. Evolution of the Structure of Ferredoxin Based on Living Relics of Primitive Amino Acid Sequences. Science. 1966;152:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3720.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Striepen B, He CY, Matrajt M, Soldati D, Roos DS. Expression, selection, and organellar targeting of the green fluorescent protein in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:325–338. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang J, Rohloff P, Miranda K, Docampo R. Ablation of a small transmembrane protein of Trypanosoma brucei (TbVTC1) involved in the synthesis of polyphosphate alters acidocalcisome biogenesis and function, and leads to a cytokinesis defect. Biochem J. 2007;407:161–170. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fang J, Marchesini N, Moreno SN. A Toxoplasma gondii phosphoinositide phospholipase C (TgPI-PLC) with high affinity for phosphatidylinositol. Biochem J. 2006;394:417–425. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanzetta PA, Alvarez LJ, Reinach PS, Candia OA. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1979;100:95–97. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shatton JB, Ward C, Williams A, Weinhouse S. A microcolorimetric assay of inorganic pyrophosphatase. Anal Biochem. 1983;130:114–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomel S, Luk FC, Beckers CJ. Host cell egress and invasion induce marked relocations of glycolytic enzymes in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000188. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Der Heyden N, Docampo R. Intracellular pH in mammalian stages of Trypanosoma cruzi is K+-dependent and regulated by H+-ATPases. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;105:237–251. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno SN, Zhong L, Lu HG, Souza WD, Benchimol M. Vacuolar-type H+-ATPase regulates cytoplasmic pH in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Biochem J. 1998;330(Pt 2):853–860. doi: 10.1042/bj3300853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanderheyden N, Benaim G, Docampo R. The role of a H(+)-ATPase in the regulation of cytoplasmic pH in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Biochem J. 1996;318(Pt 1):103–109. doi: 10.1042/bj3180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton SD, Pardue HL. Quantitation of lactate by a kinetic method with an extended range of linearity and low dependence on experimental variables. Clin Chem. 1984;30:226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engel PC, Jones JB. Causes and elimination of erratic blanks in enzymatic metabolite assays involving the use of NAD+ in alkaline hydrazine buffers: improved conditions for the assay of L-glutamate, L-lactate, and other metabolites. Anal Biochem. 1978;88:475–484. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heikinheimo P, Lehtonen J, Baykov A, Lahti R, Cooperman BS, Goldman A. The structural basis for pyrophosphatase catalysis. Structure. 1996;4:1491–1508. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohsaka A, Yoshikawa K, Hagiwara T. 1H-NMR spectroscopic study of aerobic glucose metabolism in Toxoplasma gondii harvested from the peritoneal exudate of experimentally infected mice. Physiol Chem Phys. 1982;14:381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akkerman JWN, Gorter G, Sixma JJ. REGULATION OF GLYCOLYTIC FLUX IN HUMAN PLATELETS: RELATION BETWEEN ENERGY PRODUCTION BY GLYCO(GENO)LYSIS AND ENERGY CONSUMPTION. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1978:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harold FM. Ion Transport and Electrogenesis in Bacteria. Proceedings of the Biochemical Society. 1979;127:1971–1972. doi: 10.1042/bj1270049p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ginsburg H. Abundant proton pumping in Plasmodium falciparum, but why? Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:483–486. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Denton H, Brown SM, Roberts CW, Alexander J, McDonald V, Thong KW, Coombs GH. Comparison of the phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase activities of Cryptosporidium parvum, Eimeria tenella and Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;76:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang J, Mullapudi N, Lancto CA, Scott M, Abrahamsen MS, Kissinger JC. Phylogenomic evidence supports past endosymbiosis, intracellular and horizontal gene transfer in Cryptosporidium parvum. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R88. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang J, Mullapudi N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Kissinger JC. A first glimpse into the pattern and scale of gene transfer in Apicomplexa. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Striepen B, White MW, Li C, Guerini MN, Malik SB, Logsdon JM, Jr, Liu C, Abrahamsen MS. Genetic complementation in apicomplexan parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6304–6309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092525699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dzierszinski F, Popescu O, Toursel C, Slomianny C, Yahiaoui B, Tomavo S. The protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii expresses two functional plant-like glycolytic enzymes. Implications for evolutionary origin of apicomplexans. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24888–24895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gomez-Garcia MR, Ruiz-Perez LM, Gonzalez-Pacanowska D, Serrano A. A novel calcium-dependent soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase from the trypanosomatid Leishmania major. FEBS Lett. 2004;560:158–166. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feagin JE, Marsons M. The Apicoplast and Mitochondrion of Toxoplasma gondii. In: Weiss LM, Kim K, editors. Toxoplasma gondii. The Model Apicomplexan-Perspectives and Methods. London: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 207–244. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin SS, Blume M, von Ahsen N, Gross U, Bohne W. Extracellular Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites do not require carbon source uptake for ATP maintenance, gliding motility and invasion in the first hour of their extracellular life. International Journal for Parasitology. 41:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamilton IR, Martin EJS. Evidence for the Involvement of Proton Motive Force in the Transport of Glucose by a Mutant of Streptococcus mutans Strain DR0001 Defective in Glucose-Phosphoenolpyruvate Phosphotransferase Activity. Infect. Immun. 1982;36:567–575. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.2.567-575.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sigler K, Knotkov A, Kotyk A. Factors governing substrate-induced generation and extrusion of protons in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1981;643:572–582. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Denton H, Roberts CW, Alexander J, Thong KW, Coombs GH. Enzymes of energy metabolism in the bradyzoites and tachyzoites of Toxoplasma gondii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chambers JW, Kearns MT, Morris MT, Morris JC. Assembly of heterohexameric trypanosome hexokinases reveals that hexokinase 2 is a regulable enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14963–14970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Acosta H, Dubourdieu M, Quinones W, Caceres A, Bringaud F, Concepcion JL. Pyruvate phosphate dikinase and pyrophosphate metabolism in the glycosome of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;138:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saito T, Maeda T, Nakazawa M, Takeuchi T, Nozaki T, Asai T. Characterisation of hexokinase in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:961–967. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geigenberger P, Hajirezaei M, Geiger M, Deiting U, Sonnewald U, Stitt M. Overexpression of pyrophosphatase leads to increased sucrose degradation and starch synthesis, increased activities of enzymes for sucrose-starch interconversions, and increased levels of nucleotides in growing potato tubers. Planta. 1998;205:428–437. doi: 10.1007/s004250050340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farre EM, Tech S, Trethewey RN, Fernie AR, Willmitzer L. Subcellular pyrophosphate metabolism in developing tubers of potato (Solanum tuberosum) Plant Mol Biol. 2006;62:165–179. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guerardel Y, Leleu D, Coppin A, Lienard L, Slomianny C, Strecker G, Ball S, Tomavo S. Amylopectin biogenesis and characterization in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, the intracellular development of which is restricted in the HepG2 cell line. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.