Abstract

We investigated the effect of West Nile virus (WNV) infection on survival in two colonies of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) originating from Vero Beach and Gainesville, FL. Mosquitoes were fed West Nile virus-infected blood and checked daily for survival. Exposure to WNV decreased survival among Cx. p. quinquefasciatus from Gainesville relative to unexposed individuals at 31° C. In contrast, exposure to WNV enhanced survival among Cx. p. quinquefasciatus from Vero Beach relative to unexposed individuals at 27° C. These results may suggest that exposure to WNV and associated infection could increase or decrease components of fitness, dependent on environmental temperature and intraspecific variation in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus. The relationship between lifespan (time of death in days) and WNV titer differed in the colonies at 31° C and 27° C, suggesting that intraspecific species variation in response to temperature impacts interactions with WNV. While further work is needed to determine if similar effects occur under field conditions, this suggests intraspecific variation in vector competence for WNV and adult survival of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus, both aspects of vectorial capacity.

Keyword Index: Adult lifespan, arbovirus infection, Flavivirus, Culex.

INTRODUCTION

The daily mortality rate of mosquitoes is an important component of vectorial capacity (Garrett-Jones 1964, Dye 1992, Luz et al. 2003). Vectors that become infected after a blood meal but fail to survive to bite another host reduce the transmission potential of the population. If vectorial capacity is assessed based on mosquito infection rates, changes in mosquito mortality rate directly influence pathogen transmission. Models of mosquitoborne pathogen transmission often assume that the mortality of adult mosquitoes is constant (Bellan 2010) because environmental factors are likely a more important cause of mortality than age-associated factors (MacDonald 1952). However, studies of Aedes aegypti (L.) demonstrated age-dependent mortality of adult females and males counter to the assumption of constant mortality (Styer et al. 2007a, Styer et al. 2007b, Harrington et al. 2008). These studies suggest that nonlinear functions (e.g., Gompertz, Weibull, logistic) are better descriptors of adult mortality than linear functions (Clements and Paterson 1981, Styer et al. 2007a, Styer et al. 2007b, Delatte et al. 2009). Few studies have examined the interactions between age-associated mortality, virus infection, and environmental temperature. Studies are needed to assess the influence of the environment on mortality. Understanding the relationship between heterogeneity in mosquito mortality rates and arbovirus transmission will improve our understanding of mosquito-borne disease.

The influence of viral infection on invertebrate hosts likely depends on biology (e.g., immunological response, nutritional reserves) or environmental conditions such as temperature. Temperature influences biochemical, physiological, and behavioral processes and is a key factor determining insect-endosymbiont interactions (Moore 2001, Thomas and Blanford 2003). The impact of parasitism may be altered by temporal and spatial variation in environmental temperature, especially in poikilotherms such as insects. Small changes in environmental temperature may alter host susceptibility to infection, recovery, parasite replication, and virulence (Thomas and Blanford 2003). Further, interactions between parasites and hosts may be dependent on parasite and host genotypes such that different genotypes can respond differently to variation in temperature (Wolinska and King 2009, Kilpatrick et al. 2008). The influence of environmental temperature on interactions between arboviruses and their mosquito hosts is likely very complex.

Macro and microparasites may impose varied fitness consequences to their mosquito vectors (Plasmodium: Vézilier et al. 2012, Ferguson and Read 2002; filarial worms: Michael et al. 2009). For arboviruses (a microparasite), some studies have found little effect of arbovirus infection on mosquito performance (Patrican and DeFoliart 1985, Dohm et al. 1991, Putman and Scott 1995), while other studies have concluded that arboviruses decreased adult lifespan (Scott and Lorenz 1998, Moncayo et al. 2000, Mahmood et al. 2004, Reiskind et al. 2010), fecundity (Scott and Lorenz 1998, Moncayo et al. 2000, Styer et al. 2007a, Styer et al. 2007c), and flight activity (Lee et al. 2000) and may alter feeding behavior (Grimstad et al. 1980, Platt et al. 1997). A meta-analysis showed that arboviruses have detrimental effects on mosquito adult lifespan that depend on taxonomic groupings of mosquitoes, virus type, and mode of transmission (horizontal or vertical) (Lambrechts and Scott 2009). The same study showed that horizontal transmission of alphaviruses is associated with reduced adult survival. These virus-induced lifespan shortening effects were not observed in mosquitoes infected transovarially by bunyaviruses. Conflicting accounts are likely related to the variance in effects of virus infection on mosquito fitness from beneficial (Gabitzsch et al. 2006, Reese et al. 2009) to highly detrimental. It is possible that viruses sometimes act as symbionts or mutualists in the mosquito, while parasitic in vertebrate hosts. There may also be differential effects on different components of fitness; under some environmental conditions, endosymbionts may enhance survival (Wolbachia: Dobson et al. 2004, Plasmodium: Zhao et al. 2012) and mating success (La Crosse virus: Gabitzsch et al. 2006, Reese et al. 2009) of mosquitoes.

Environmental conditions and time since infection are also important, as higher temperatures support faster replication and lead to higher viral titers (Dohm et al. 2002), but increased mortality (Gunay et al. 2010). The relationship between arbovirus titer at time of death and adult survival is likely complex. Characterizing arbovirus titer at time of death for mosquitoes in different states of infection (non-disseminated vs disseminated infections) is essential to begin to understand the relationships between adult survival and factors like infection and temperature.

The aim of this study was to characterize the influence of environmental temperature and exposure to West Nile virus (WNV) on mortality in the Southern house mosquito Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say. Culex p. quinquefasciatus plays a role in the maintenance of WNV in bird populations as well as transmission to humans (Sardelis et al. 2001, Rutledge et al. 2003, Hayes et al. 2005). The current study provides information on the relationship between adult mosquito longevity, temperature, and WNV infection for two mosquito colonies. We tested whether: 1) Cx. p. quinquefasciatus exposure to WNV lowers longevity in relation to environmental temperature and colony and 2) lifespan is inversely related to WNV titer (virus load) in relation to environmental temperature and colony.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used established laboratory colonies of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus individuals field-collected from Gainesville (generation F84) and Vero Beach (generation F35), FL. Although these mosquitoes were collected from different sources, they may not be representative of field populations given that they have been maintained in the laboratory for many generations. Thus, here we consider these mosquitoes simply as two separate laboratory colonies. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus adult females were allowed to blood-feed on WNV-infected blood or control blood meals lacking virus. Fully engorged females were maintained at either 27° C or 31° C until death. We measured infection and dissemination rates of WNV, viral titer, and daily survival.

Preparation of infectious blood meals

We used WNV strain WN-FL03p2-3 from Florida (GenBank: DQ983578.1). Propagation of WNV for blood meals was accomplished by inoculating confluent monolayes of Vero cells in tissue culture flasks (150 cm2) (containing 12 ml media: 199 media, 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.2% amphotericin B (Fungizone®), 2% penicillin-streptomycin) with 0.2 ml virus stock. Tissue culture flasks with virus and media were then placed in an incubator at 35° C with a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Control blood meals lacking WNV were prepared using similar methods except cells were inoculated with media lacking WNV. Inoculation of tissue culture flasks with virus and media were completed 48 h prior to blood-feeding trials. On the day of blood-feeding, freshly harvested media and virus from tissue culture flasks containing Vero cells (controls used media in flask with Vero cells) were combined with chicken blood using a 1:100 dilution of freshly propagated virus + media:blood.

Mosquitoes and blood feeding

Culex p. quinquefasciatus were reared using standard conditions (Richards et al. 2009). Mosquitoes that emerged over a two-day period were used in the experiment. Female Cx. p. quinquefasciatus were held after emergence with males and then transferred to 1 liter cardboard cages with mesh screening (~150 females/cage). Mosquitoes were deprived of sugar but not water 24 h before blood-feeding trials, at which time seven- to eight-day-old females were provided blood-soaked cotton pledgets containing 3 ml of WNV-infected chicken blood containing Alsever’s as an anticoagulant (Hemostat Laboratories, Dixon, CA). The blood-virus laden pledgets were first heated at 35° C for 10 min and then placed on cages containing mosquitoes for 45 min to allow feeding. Control mosquitoes were handled similarly except that they were allowed to feed on uninfected blood (i.e., unexposed). A single feeding trial was provided to each of the Cx. p. quinquefasciatus colonies. Logistic constraints prevented us from feeding the two colonies at the same time. Immediately after feeding, ten fully engorged females fed infected blood from each feeding trial were stored at −80° C to determine viral titers of freshly fed mosquitoes between feeding trials.

After blood-feeding, mosquitoes were cold anesthetized and each fully engorged female was transferred to its own 0.5 liter cardboard cage with mesh screening along with a 30 ml plastic cup containing 10 ml tap water attached to the bottom of the cage for an oviposition site. Cotton moistened with a 20% sugar solution was placed on top of the mesh screening to provide carbohydrate nutrients. Mosquitoes were kept at either 27° C or 31° C, with 70–80% humidity and a 14:10 L:D photo regime. Treatment temperatures approximate early transmission phases (27° C) and the upper limit during early transmission phase (31° C) in areas of Florida for WNV activity (National Oceanic Administration Association, http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/ulcd/ULCD) (Richards et al. 2007). Mosquitoes were monitored daily to check for adult survival and dead specimens were transferred to 2.0 ml tubes and stored at −80° C for subsequent analysis. The time between emergence to adulthood and death determined adult lifespan. We used lifespan to estimate survival rates for each treatment group. Survival function estimates describe the shape of mortality over time, whereas lifespan describes time of death in days.

Mosquito processing

Adult females stored at −80° C were processed by removing legs from the remainder of the body. Bodies and legs were assayed to determine infection and dissemination rates of WNV as well as viral titer. Samples were triturated separately in 2.0 ml microcentrifuge tubes with two 4.5-mm stainless steel beads and 0.9 ml BA-1 (10× medium 199, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.05 M TRIS, pH 7.5, 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, 1 μg/ml of mycostatin) at 25 Hz for 3 min (TissueLyser, Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) and subsequently centrifuged at 3,148 × g for 4 min at 4° C. Nucleic acids were extracted as previously described (Richards et al. 2009). The amount of viral RNA present in samples was determined using quantitative real-time TaqMan Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction with a Light Cycler 480 system® (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) (Richards et al. 2007). The amount of WNV RNA present in samples was expressed in plaque forming unit equivalents (pfue)/ml using a standard curve method that compared cDNA synthesis for a range of serial dilutions of WNV in parallel with plaque assays using the same dilutions of virus (Bustin 2000, Richards et al. 2007). Infection is defined as mosquitoes with WNV RNA in their bodies. Dissemination is defined as mosquitoes with WNV RNA in both their bodies and legs. Uninfected individuals refer to mosquitoes that fed on WNV-infected blood but lacked detectable virus RNA in their bodies.

Statistical analyses

Prior to analyzing effects of WNV exposure on survival, we examined temperature and colony treatment effects on infection, dissemination, and viral titer of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus. Infection rate was defined as the number with body infections divided by the number that fed on WNV-infected blood; dissemination rate was defined as the number with body and leg infections divided by the number that fed on WNV-infected blood. Infection and dissemination rates are expressed as percentages of the total. Treatment effects on susceptibility to WNV infection and dissemination were analyzed using goodness of fit tests (Pearson’s Chi-square statistic). Treatment effects on viral titer in bodies and legs were characterized using analysis of variance. When significant effects were detected, we used pairwise comparisons of means adjusted for α = 0.05 (Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons, PROC GLM, SAS 9.22). Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to analyze body and leg titers of mosquitoes with disseminated infections because these data did not meet the assumption of normality. Separate Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for effects of colony and temperature. Nonparametric methods have limited capabilities to test for interactions (Gaito 1959), so data were reorganized so that each colony and temperature treatment represented a single treatment (Vero Beach at 27° C, Vero Beach at 31°C, Gainesville at 27° C, Gainesville at 31° C; yielding four individual treatments). A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze these new treatment combinations as a proxy for a treatment interaction test (Costanzo et al. 2011). Follow-up tests consisted of pairwise contrasts of treatments (e.g., Vero Beach at 27° C vs Vero Beach at 31° C) using similar nonparametric methods correcting for multiple comparisons using the sequential Bonferroni method.

Treatment effects on survival were compared between WNV exposed and control Cx. p. quinquefasciatus using non-parametric survival analysis (PROC LIFETEST, SAS 9.22). Follow-up procedures used log-rank test statistics to compare pairwise estimates of survival adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Sidak method (Sidak 1967). Analysis of covariance models, treating lifespan (time) as a covariate, tested the null hypothesis of equal slopes for the two colonies relating body viral titer among Cx. p. quinquefasciatus with disseminated infections and lifespan. Separate tests were performed for 27° C and 31° C.

RESULTS

A total of 520 Cx. p. quinquefasciatus adult females fed on WNV-infected blood (273 mosquitoes) or control blood (247 mosquitoes). For each colony and temperature, a minimum of 64 mosquitoes were used per treatment for the cohorts of mosquitoes fed WNV-infected blood. Virus titers of freshly fed mosquitoes were 5.1 ± 0.33 and 4.8 ± 0.30 log10 pfue WNV/ml for Cx. p. quinquefasciatus from Gainesville and Vero Beach, respectively.

Infection and dissemination rates

West Nile virus infection and dissemination rates differed between the two colonies and these differences depended on environmental temperature. Infection and dissemination rates for both colonies at 27° C and 31° C are listed in Table 1. Goodness of fit tests showed no significant differences in infection rates between the colonies at 31° C (χ2 = 0.241, 1 d.f., p = 0.6238; Table 1). However, dissemination rates were significantly higher for the Gainesville than Vero Beach colony at 31° C (χ2 = 4.603, 1 d.f., p = 0.0319; Table 1). Infection and dissemination rates were significantly higher for the Gainesville colony compared to the Vero Beach colony at 27° C (infection, χ2 = 6.357, 1 d.f., p = 0.0117; dissemination, χ2 = 5.409, 1 d.f., p = 0.0200; Table 1).

Table 1.

Infection and dissemination rates for Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus from Gainesville and Vero Beach, FL fed WNV-infected blood and maintained at 27° C and 31° C. Body titer measurements are reported for individual females with non-disseminated (non-D) and disseminated (D) infections. Goodness of fit tests (Pearson’s Chi-square statistic) were used to test for differences in infection and dissemination at 31° C (lowercase letters denote significant differences) and 27° C (uppercase letters denote significant differences). ANOVA (non-D) and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for differences between treatment groups in body and leg titer (D) (treatment groups with the same superscript letter in each titer column are not significantly different).

| Colony | Temperature (° C) | No. tested | No. infected | No. disseminated | Body titer‡ (non-D) | Body titer‡ (D) | Leg titer‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vero Beach | 31 | 65 | 62 (95)a | 49 (75)a | 5.89 (0.44)a | 7.9 (0.13)a | 5.7 (0.14)a |

| Gainesville | 31 | 67 | 65 (97)a | 60 (90)b | 5.64 (0.72)a | 8.8 (0.12)b | 6.5 (0.13)b |

| Vero Beach | 27 | 64 | 53 (83)A | 45 (70)A | 5.73 (0.57)a | 8.8 (0.14)b | 6.7 (0.15)b |

| Gainesville | 27 | 73 | 70 (96)B | 64 (86)B | 6.27 (0.60)a | 8.2 (0.12)a | 5.9 (0.12)a |

Log10 plaque-forming unit equivalents West Nile virus per milliliter (S.E., standard error).

West Nile virus titer

We observed no differences in body titers of mosquitoes with non-disseminated infections between colonies or temperatures (all F ≤ 0.16, all p ≥ 0.51; Table 2). There was a significant interaction between temperature and colony for body titer in mosquitoes with infections disseminated to the legs (χ2 = 24.61, p < 0.0001; Table 2). At 27° C significantly higher body titers were observed in females from the Vero Beach colony compared to the Gainesville colony (χ2 = 14.68, p = 0.0001; Table 1). Conversely, at 31° C significantly higher body titers were observed in females from the Gainesville colony compared to Vero Beach colony (χ2 = 9.95, p = 0.0016; Table 1). There was a significant interaction between colony and temperature effects on leg titers of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus with disseminated infections (all χ2 ≥ 12.48, p ≤ 0.0004; Tables 1, 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of variance and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests of treatment effects on viral titer in Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus from Gainesville and Vero Beach, FL, fed WNV-infected blood and maintained at 27° C and 31° C.

| Body part | Status of infection | Source | d.f. | F | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body | Non-disseminated infection | Temperature | 1 | 0.16 | . | 0.6889 |

| Colony | 1 | 0.06 | . | 0.8069 | ||

| Temperature × Colony | 1 | 0.44 | . | 0.5138 | ||

| Error | 29 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Body | Disseminated infection | Temperature | 1 | . | 0.06 | 0.8011 |

| Colony | 1 | . | 0.00 | 0.9765 | ||

| Temperature × Colony | 3 | . | 24.61 | <0.0001 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Legs | Disseminated infection | Temperature | 1 | . | 0.26 | 0.6040 |

| Colony | 1 | . | 0.62 | 0.4275 | ||

| Temperature × Colony | 3 | . | 39.50 | <0.0001 | ||

Survival of West Nile virus-exposed mosquitoes

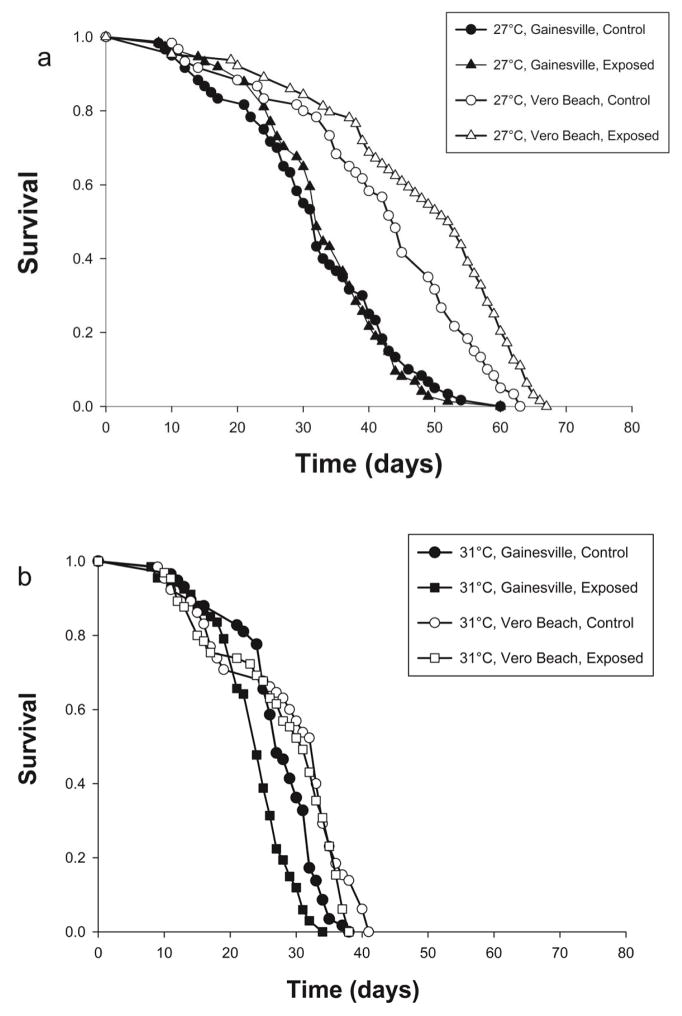

Survival of adult females depended on colony, temperature, and type of blood meal (WNV exposed and unexposed). All two-way interactions and the three-way interaction [Temperature × Colony × Type of blood meal] were significant (Table 3). Thus, the colonies respond differently to temperature and infection. To further investigate the highest order interaction (three-way interaction), we examined pairwise comparisons of survival of mosquitoes exposed and unexposed (controls) to WNV within each temperature by colony combination. At 27° C, the Vero Beach Cx. p. quinquefasciatus exposed and unexposed to WNV showed significantly greater survival than the Gainesville Cx. p. quinquefasciatus exposed and unexposed to WNV (all χ2 ≥ 12.18, p ≤ 0.0004, Figure 1a). At 27° C, Gainesville Cx. p. quinquefasciatus showed no differences in survival for exposed vs unexposed to WNV (χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.90, Figure 1a). At 27° C, Vero Beach Cx. p. quinquefasciatus exposed to WNV had significantly greater survival than unexposed mosquitoes (χ2 = 8.22, p = 0.0041, Figure 1a). At 31° C, the Vero Beach Cx. p. quinquefasciatus exposed and unexposed to WNV had significantly greater survival than in Gainesville Cx. p. quinquefasciatus exposed to WNV (all χ2 ≥ 7.01, p ≤ 0.008, Figure 1b), but not the unexposed mosquitoes (all χ2 ≤ 0.99, p ≥ 0.31, Figure 1b). At 31° C, Gainesville Cx. p. quinquefasciatus not exposed to WNV had marginally greater survival than exposed mosquitoes, after correcting for multiple comparisons (χ2 = 5.21, p = 0.0225, Figure 1b).

Table 3.

Non-parametric survival analysis of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus from Gainesville and Vero Beach, FL, fed WNV-infected or control blood (no WNV) and maintained at 27° or 31° C.

| Source | d.f. | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 1 | 157.20 | <0.0001 |

| Colony | 1 | 64.71 | <0.0001 |

| Type of blood | 1 | 1.08 | 0.29 |

| Temperature × Colony | 3 | 241.75 | <0.0001 |

| Temperature × Type of blood | 3 | 167.62 | <0.0001 |

| Colony × Type of blood | 3 | 69.44 | <0.0001 |

| Temperature × Colony × Type of blood | 7 | 262.41 | <0.0001 |

Figure 1.

Survival of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus from Gainesville (G) and Vero Beach (VB), FL, exposed to WNV-infected or control blood (no WNV). Figure panels show results for an interaction between temperature, geographic origin of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus (colony), and type of blood meal (WNV infected, control). Lifespan was measured for 513 total female adults at (a) 27° C, and (b) 31° C. Pairwise comparisons were made between individuals being exposed to WNV-infected or control blood meals. Median and interquartile range (Q1–Q3) longevity for each treatment group are as follows; 27° C-VB-exposed, 53 (39–60), 27°C–VB-unexposed, 45 (34.5–55.5), 27° C-G-exposed, 32 (26–40), 27°C-G-unexposed, 32 (24.3–40.8), 31° C-VB-exposed, 31 (17–35), 31° C-VB-unexposed, 33 (18–35), 31° C-G-exposed, 24 (21–27), 31° C-G-unexposed, 27 (25–32).

Survival and West Nile virus titer

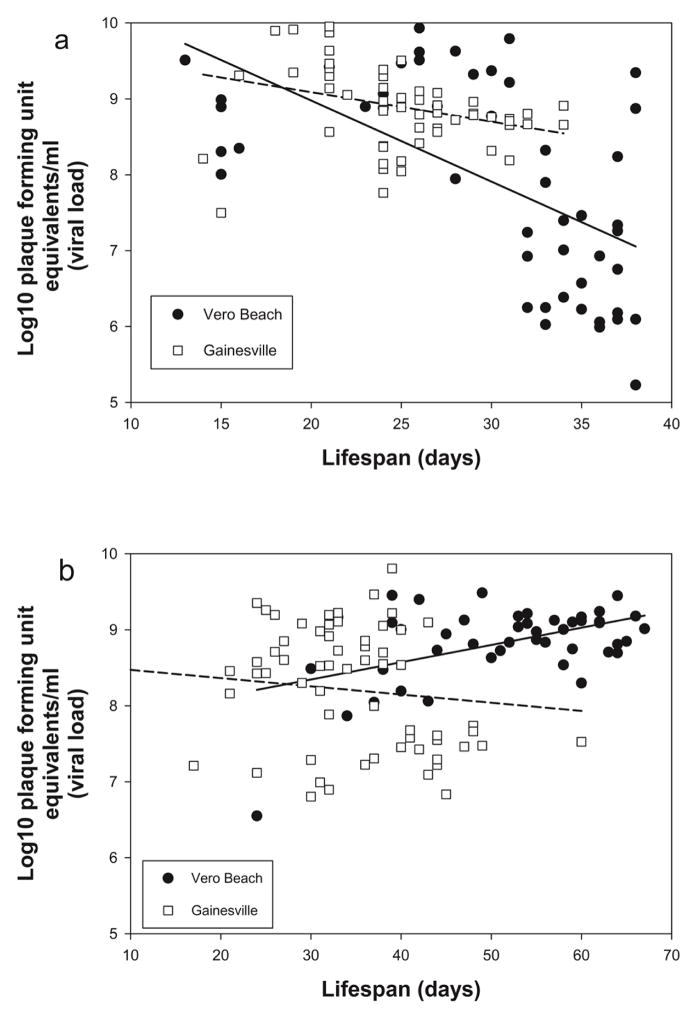

Analysis of covariance models, with lifespan (time) as a covariate, were used to test the null hypothesis of equal slopes for the two colonies relating body viral titer among Cx. p. quinquefasciatus with disseminated infections and lifespan. At both temperatures, a significant time × colony interaction enabled us to reject the null hypothesis, providing evidence that the slopes were not equivalent (31° C, F = 5.17, p = 0.0250; 27° C, F = 4.86, p = 0.0297, Table 4, Figure 2). Therefore, the relationship of lifespan and body titer at time of death differed between the colonies. Since the slopes were unequal, a model was used to obtain slope estimates and test the null hypothesis that the slope equals zero. The estimated slope was not significantly different from zero for the Gainesville mosquitoes at 31° C (slope = −0.0387, S.E. = 0.0247, t = −1.56, p = 0.1208). In the Vero Beach mosquitoes, WNV titer at 31° C decreased with greater lifespan in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus with disseminated infections (slope = −0.1068, S.E. = 0.0167, t = −6.37, p < 0.0001). The slope for Vero Beach mosquitoes was more negative than for Gainesville mosquitoes (Figure 2a), indicating a more rapid decrease in titer in longer-lived mosquitoes. The estimated slope was not significantly different from zero for Gainesville mosquitoes at 27° C (slope = −0.0108, S.E. = 0.0108, t = −0.99, p = 0.3227). The estimated positive slope showed that WNV titer in Vero Beach mosquitoes increased with increased lifespan for mosquitoes with disseminated infections at 27° C (slope = 0.0227, S.E. = 0.0106, t = 2.14, p = 0.0348).

Table 4.

Analysis of covariance models, with time (day of death) as covariate, to test the null hypothesis of equal slopes for the two colonies relating body viral titer among Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus with disseminated infections and lifespan.

| Temperature | Source | d.f. | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27° C | Time | 1 | 0.61 | 0.4357 |

| Colony | 1 | 1.83 | 0.1792 | |

| Time × Colony | 1 | 4.86 | 0.0297 | |

| Error | 104 | |||

|

| ||||

| 31° C | Time | 1 | 23.67 | <0.0001 |

| Colony | 1 | 2.37 | 0.1268 | |

| Time × Colony | 1 | 5.17 | 0.0250 | |

| Error | 104 | |||

Figure 2.

Body titer and lifespan of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus from Gainesville and Vero Beach, FL with disseminated WNV infections maintained at (a) 31° C and (b) 27° C. Dashed and solid lines drawn through viral titer values show the best fit for Gainesville and Vero Beach colonies, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study we characterized relationships among WNV infection, adult survival, and temperature using two Cx. p. quinquefasciatus colonies. We observed that infection and dissemination rates increased with higher temperature. These results are similar to studies examining the impact of temperature on Cx. p. quinquefasciatus and Cx. p. pipiens vector competence for WNV (Richards et al. 2007, Dohm et al. 2002, Eastwood et al. 2011). Differences in infection and dissemination rates between the colonies used here were consistent with other studies showing genetic variation between different colonies and populations (Bennett et al. 2002, Vaidyanathan and Scott, 2007). While the two colonies used here are long-established lab colonies and so may not reflect what occurs in field situations, these differences demonstrate the variation possible within one species, despite having adapted to similar (lab) conditions. Higher infection and dissemination rates were observed in mosquitoes from Gainesville compared to Vero Beach at 27° C. Similar trends were observed at 31° C but were only significant when dissemination rates were considered (Table 1). Another study that used the same colonies under similar conditions (freshly fed mosquitoes containing 5.2–5.3 log10 pfue; environmental temperature 28° C; 7-day-old mosquitoes) and incubated for 13 days showed no significant differences in infection or dissemination rates in Gainesville compared to Vero Beach colonies (Richards et al. 2010). However, the two colonies differed in WNV infection and dissemination under different biological (mosquito age) and environmental (temperature, virus dose) conditions, and the aforementioned study showed that factors interacted in complex ways to affect measures of vector competence.

The relationship between body and leg titers of infected mosquitoes and dissemination status differed between the two colonies. At 27° C, viral titers in bodies and legs of mosquitoes with disseminated infections were higher in individuals from Vero Beach than Gainesville, while at 31° C, titers were higher in Gainesville than Vero Beach mosquitoes. However, there were no differences in body titer in mosquitoes with non-disseminated infections. Non-disseminated infections are limited to the midgut by the midgut (mesenteronal) escape barrier (Kramer et al. 1981). This barrier prevents viral escape across the basal lamina of the midgut and disseminating to other tissues (Defoliart et al. 1987). Under the conditions used here, colony-specific differences in infection and dissemination rates, related to viral growth, occurred only after WNV overcame the midgut escape barrier.

Ingestion of arbovirus-infected blood can elicit an immune response in mosquitoes (Ahmed et al. 2002, Schwartz and Koella 2004, Khoo et al. 2010, Ramirez and Dimopoulos 2010). Mounting an immune response is metabolically costly and may reduce mosquito fitness (e.g., decrease in reproductive fitness) (Moore 2001, Ahmed et al. 2002, Schwartz and Koella, 2004). If mosquitoes suffer a metabolic cost attributable to arbovirus infection, then decreased survival may be associated with virus-exposed compared to unexposed mosquitoes. Virus exposure, even if infection is unsuccessful, may pose a metabolic cost (Ciota et al. 2011, Maciel-de-Freitas et al. 2011) due to the initiation of immune responses. Following exposure, immune responses may clear or limit the infection, or fail to control the infection resulting in dissemination through the body. Costs of such defenses or viral dissemination through the body of the mosquito may influence adult survival. For instance, mounting an immune defense may result in earlier mortality in individuals who are only exposed to virus but not infected, or never experience virus dissemination to tissues (Ciota et al. 2011, Maciel-de-Freitas et al. 2011). Conversely, if viral infection and replication are costly to the mosquito, then higher viral titers may be associated with mosquitoes that die earlier.

Differences in WNV titers observed here may be attributable to differences in WNV replication in the two Cx. p. quinquefasciatus colonies. However, differences in titers between the colonies could also be due to mosquitoes living longer at 27° C than 31° C, and that the Vero Beach mosquitoes lived longer than the Gainesville mosquitoes. Taken together, differences in titers between the colonies used in this study could result from longer time for viral replication. After controlling for a time effect, we showed that relationships between lifespan and titer differed in the colonies at 31° C and 27° C, suggesting that within species variation in response to environmental temperature impacts interactions with WNV. We observed a decreasing relationship between viral titer and lifespan in mosquitoes with disseminated infections suggesting a cost to viral replication. However, these effects were only observed for the Vero Beach colony at 31° C. A positive relationship between viral titer and lifespan for mosquitoes from the Vero Beach colony held at 27° C suggest that costs to viral replication are minimal and depend on environmental temperature and geographic origin of the mosquito species. While factors such as environmental temperature, virus dose, virus strain, and mosquito chronological age influence Cx. p. quinquefasciatus vector competence for WNV, between-factor interactions that affect vector competence must be considered when interpreting experimental results (Richards et al. 2010). Future studies should determine genetic variation controlling vector competence between geographic populations of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus and the nature of extrinsic and intrinsic interactions with environmental and biologic factors (e.g., Culex p. pipiens and Cx. restuans and West Nile virus, Kilpatrick et al. 2010). Studies should determine whether observations from the current study using colonized Cx. p. quinquefasciatus translate to the field where populations may be more genetically heterogeneous and environmental conditions more variable.

We tested the hypothesis that exposure to WNV decreases survival in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus. The higher temperature treatment here resulted in approximately 30% reduction in survival, consistent with other mosquito species where increases in temperature reduce adult survival (Nayar 1972, Oda et al. 1999, Alto and Juliano, 2001). The significant interactions including colony and temperature in the survival analysis indicates that the two colonies are responding differently to temperature. We found modest support for the prediction that exposure to WNV impedes survival (i.e., Gainesville Cx. p. quinquefasciatus at 31° C) which would suggest a cost of immune activation in response to a virus challenge, consistent with observations for other mosquitoes (Cx. p. pipiens and WNV: Ciota et al. 2011, Aedes aegypti and dengue-2 virus: Maciel-de-Freitas et al. 2011, Anopheles gambiae Giles and Ae. aegypti: Ahmed et al. 2002, Schwartz and Koella 2004). However, this effect depended on environmental temperature and varied between colonies of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus. In contrast, exposure to WNV enhanced survival for Vero Beach Cx. p. quinquefasciatus at 27° C. These results suggest that exposure to WNV and associated infection affects components of mosquito fitness. Arbovirus associated benefits in mosquito survival, reproduction, or changes in mosquito blood-feeding behavior may increase the efficiency of transmission. Longer probing and feeding periods (dengue virus infected Aedes aegypti: Platt et al. 1997, La Crosse encephalitis virus (LACV) infected Aedes triseriatus: Grimstad et al. 1980) may lead to more interrupted feedings and feeding on multiple hosts. La Crosse encephalitis virus infection of Ae. triseriatus was associated with improved insemination rates (Gabitzsch et al. 2006, Reese et al. 2009) and hatching rate of viable eggs (McGaw et al. 1998). However, the potential benefits of higher insemination associated with infection may be offset by other detrimental effects of LACV infection including greater egg mortality (McGaw et al. 1998), which may influence vertical transmission (Miller et al. 1977, Hughes et al. 2006). These findings for arboviruses complement other mosquito-endosymbiont systems where fitness advantages were observed for Wolbachia infected Aedes albopictus (e.g., greater fecundity and longevity, Dobson et al. 2004) and survival was enhanced under starvation for Plasmodium infected Anopheles stephensi (Zhao et al. 2012). The observation that mosquito lifespan could increase with exposure to WNV indicates that these fitness advantages may occur for arboviruses and warrant further study to understand when this may occur and the consequences for arbovirus transmission. The mechanisms that cause WNV-associated changes in survival are unclear but suggest a high degree of complexity between WNV and Cx. p. quinquefasciatus. Improving our understanding of WNV-induced changes in fitness related traits will provide insight into transmission in nature.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Hussain and H. Lynn for assistance with daily maintenance of the experiment, and C. Smartt and W. Tabachnick for reviewing earlier versions of the manuscript. This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI-42164 to C. Lord and funds from the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida to B. Alto.

REFERENCES CITED

- Ahmed AM, Baggott SL, Hurd H. The costs of mounting an immune response are reflected in the reproductive fitness of the mosquito. Anopheles gambiae Oikos. 2002;97:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Alto BW, Juliano SA. Precipitation and temperature effects on populations of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae): Implications for range expansion. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:646–656. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.5.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellan SE. The importance of age dependent mortality and the extrinsic incubation period in models of mosquito-borne disease transmission and control. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KE, Olson KW, Munoz ML, Bernandez-Salas I, Farfan-ale JA, Higgs S, Black WC, 4th, Beaty BJ. Variation in vector competence for dengue 2 virus among 24 collections of Aedes aegypti from Mexico and the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:85–92. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25:169–193. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciota AT, Styer LM, Meola MA, Kramer LD. The costs of infection and resistance as determinants of West Nile virus susceptibility in Culex mosquitoes. BMC Ecol. 2011;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN, Paterson GD. The analysis of mortality and survival rates in wild populations of mosquitoes. J Appl Ecol. 1981;18:373–399. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo KS, Muturi EJ, Lampman R, Alto BW. The effects of resource type and ratio on competition with Aedes albopictus and Culex pipeins (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2011;48:29–38. doi: 10.1603/me10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFoliart GR, Grimstad PR, Watts DM. Advances in mosquito-borne arbovirus/vector research. Annu Rev Entomol. 1987;32:479–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.002403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delatte H, Gimonneau G, Triboire A, Fontenille D. Influence of temperature on immature development, survival, longevity, fecundity, and gonotrophic cycles of Aedes albopictus, vector of chikungunya and dengue in the Indian Ocean. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:33–41. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson SL, Rattanadechakul W, Marsland EJ. Fitness advantage and cytoplasmic incompatibility in Wolbachia single- and superinfected Aedes albopictus. Heredity. 2004;93:135–142. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohm DJ, Romoser WS, Turell MJ, Linthicum KJ. Impact of stressful conditions on the survival of Culex pipiens exposed to Rift Valley fever virus. J Am Mosq Contr Assoc. 1991;7:621–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohm DJ, O’Guinn ML, Turell MJ. Effect of environmental temperature on the ability of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit West Nile virus. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:221–225. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye C. The analysis of parasite transmission by bloodsucking insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood G, Kramer LD, Goodman SJ, Cunningham AA. West Nile virus vector competency of Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes in the Galápagos Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:426–433. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaito J. Non-parametric methods in psychological research. Physiol Rep. 1959;5:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson HM, Read AF. Why is the effect of malaria parasites on mosquito survival still unresolved? Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:256–261. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabitzsch ES, Blair CD, Beaty BJ. Effect of La Crosse virus on insemination rates in female Aedes triseriatus. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:850–852. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[850:eolcvi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Jones C. The human blood index of malaria vectors in relation to epidemiological assessment. Bull Wld Hlth Org. 1964;30:241–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimstad PR, Ross QE, Craig GB., Jr Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) and La Crosse virus II. Modification of mosquito feeding behavior by virus infection. J Med Entomol. 1980;17:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/17.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunay F, Alten B, Ozsoy ED. Estimating reaction norms for predictive population parameters, age specific mortality, and mean longevity in temperature-dependent cohorts of Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) J Vector Ecol. 2010;35:354–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2010.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, Montgomery SP, O’Leary DR, Campbell GL. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1167–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington LC, Vermeylen F, Jones JJ, Kitthawee S, Sithiprasasna R, Edman JD, Scott TW. Age-dependent survival of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) demonstrated by simultaneous release - recapture of different age cohorts. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:307–313. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[307:asotdv]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MT, Gonzalez JA, Reagan KL, Blair CD, Beaty BJ. Comparative potential of Aedes triseriatus, Aedes albopictus, and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to transovarially transmit La Crosse Virus. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:757–761. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[757:cpoata]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo CCH, Sanchez-Vargas I, Olson KE, Franz AWE. The RNA interference pathway affects midgut infection-and escape barriers for Sindbis virus in Aedes aegypti. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick AM, Meola MA, Moudy RM, Kramer LD. Temperature, viral genetics, and the transmission of West Nile virus by Culex pipiens mosquitoes. PLoS Pathol. 2008;4:e1000092. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick AM, Fonseca DM, Ebel GD, Reddy MR, Kramer LD. Spatial and temporal variation in vector competence of Culex pipiens and Cx. restuans mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:607–613. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer LD, Hardy JL, Presser SB, Houk EJ. Dissemination barriers for western equine encephalomyelitis virus in Culex tarsalis infected after ingestion of low viral doses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:190–197. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts L, Scott TW. Mode of transmission and the evolution of arbovirus virulence in mosquito vectors. Proc Roy Soc B. 2009;276:1369–1378. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Rowley WA, Platt KB. Longevity and spontaneous flight activity of Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae) infected with western equine encephalomyelitis virus. J Med Entomol. 2000;37:187–193. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz PM, Codeco CT, Massad E, Struchiner CJ. Uncertainties regarding dengue modeling in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:871–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald G. The analysis of the sporozoite rate. Trop Dis Bull. 1952;49:569–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel-de-Freitas R, Koella JC, Lourenco-de-Oliveira R. Lower survival rate, longevity and fecundity of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) females orally challenged with dengue virus serotype 2. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood F, Reisen WK, Chiles RE. Western equine encephalomyelitis virus infection affects the life table characteristics of Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2004;41:982–986. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.5.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaw MM, Chandler LJ, Waseiloski LP, Blair CD, Beaty BJ. Effect of La Crosse virus infection on overwintering of Aedes triseriatus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:168–175. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael E, I, Snow C, Bockarie MJ. Ecological meta-analysis of density-dependent processes in the transmission of lymphatic filariasis: Survival of infected vectors. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:873–880. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BR, DeFoliart GR, Yuill TM. Vertical transmission of La Crosse virus (California encephalitis group): transovarial and filial infection rates in Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1977;14:437–440. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/14.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncayo AC, Edman JD, Turell MJ. Effect of eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus on the survival of Aedes albopictus, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, and Coquillettidia perturbans (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2000;37:701–706. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. Parasites and the Behavior of Animals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nayar JK. Effects of constant and fluctuating temperatures on life span of Aedes taeniorhynchus adults. J Insect Physiol. 1972;18:1303–1313. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(72)90259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Uchida K, Mori A, Mine M, Eshita Y, Kurokawa K, Kato K, Tahara H. Effects of high temperature on the emergence and survival of adult Culex pipiens molestus and Culex quinquefasciatus in Japan. J Am Mosq Contr Assoc. 1999;15:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrican LA, DeFoliart GR. Lack of adverse effect of transovarially acquired La Crosse virus infection on the reproductive capacity of Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1985;22:604–611. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/22.6.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt KB, Linthicum KJ, Myint KSA, Innis BL, Lerdthusnee K, Vaughn DW. Impact of dengue virus infection on feeding behavior of Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:119–125. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putman JL, Scott TW. Blood-feeding behavior of dengue-2 virus-infected Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:225–227. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Toll immune signaling pathway control conserved anti-dengue defenses across diverse Ae. aegypti strains and against multiple dengue virus serotypes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese SM, Beaty MK, Gabitzsch E, Blair CD, Beaty BJ. Aedes triseriatus females transovarially infected with La Crosse virus mate more efficiently than uninfected mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:1152–1158. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiskind MH, Westbrook CJ, Lounibos LP. Exposure to chikungunya virus and adult longevity in Aedes aegypti (L.) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) J Vector Ecol. 2010;35:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2010.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Mores CN, Lord CC, Tabachnick WJ. Impact of extrinsic incubation temperature and virus exposure on vector competence of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) for West Nile virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:629–636. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Lord CC, Pesko KA, Tabachnick WJ. Environmental and biological factors influencing Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) vector competence for St. Louis encephalitis virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:264–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Lord CC, Pesko KN, Tabachnick WJ. Environmental and biological factors influencing Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) vector competence for West Nile virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:126–134. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge CR, Day JF, Lord CC, Stark LM, Tabachnick WJ. West Nile virus infection rates in Culex nigripalpus (Diptera: Culicidae) do not reflect transmission rates in Florida. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:253–258. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardelis M, Turell M, Dohm D, O’Guinn M. Vector competence of selected North American Culex and Coquillettidia mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:1018–1022. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A, Koella JC. The cost of immunity in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti depends on immune activation. J Evol Biol. 2004;17:834–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TW, Lorenz LH. Reduction of Culiseta melanura fitness by eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:341–346. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidak Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62:626–633. [Google Scholar]

- Styer LM, Carey JR, Wang JL, Scott TW. Mosquitoes do senesce: departure from the paradigm of constant mortality. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007a;76:111–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer LM, Minnick SL, Sun AK, Scott TW. Mortality and reproduction dynamics of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) fed human blood. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007b;7:86–98. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer LM, Meola MA, Kramer LD. West Nile virus infection decreases fecundity of Culex tarsalis females. J Med Entomol. 2007c;44:1074–1085. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[1074:wnvidf]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MB, Blanford S. Thermal biology in insect-parasite interactions. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:344–350. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan R, Scott TW. Geographic variation in vector competence for West Nile virus in the Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) complex in California. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:193–198. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vézilier J, Nicot A, Gandon S, Rivero A. Plasmodium infection decreases fecundity and increases survival of mosquitoes. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279:4033–4041. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinska J, King KC. Environment can alter selection in host-parasite interactions. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YO, Kurscheid S, Zhang Y, Liu L, Zhang L, Loeliger K, Fikrig E. Enhanced survival of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes during starvation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]