Abstract

The antineoplastic and antibiotic natural product mithramycin (MTM) is used against cancer-related hypercalcemia and, experimentally, against Ewing sarcoma and lung cancers. MTM exerts its cytotoxic effect by binding DNA as a divalent metal ion (Me2+)-coordinated dimer and disrupting the function of transcription factors. A precise molecular mechanism of action of MTM, needed to develop MTM analogues selective against desired transcription factors, is lacking. Although it is known that MTM binds G/C-rich DNA, the exact DNA recognition rules that would allow one to map MTM binding sites remain incompletely understood. Towards this goal, we quantitatively investigated dimerization of MTM and several of its analogues, MTM SDK (for Short side chain, DiKeto), MTM SA-Trp (for Short side chain and Acid), MTM SA-Ala, and a biosynthetic precursor premithramycin B (PreMTM B), and measured the binding affinities of these molecules to DNA oligomers of different sequences and structural forms at physiological salt concentrations. We show that MTM and its analogues form stable dimers even in the absence of DNA. All molecules, except for PreMTM B, can bind DNA with the following rank order of affinities (strong to weak): MTM = MTM SDK > MTM SA-Trp > MTM SA-Ala. An X(G/C)(G/C)X motif, where X is any base, is necessary and sufficient for MTM binding to DNA, without a strong dependence on DNA conformation. These recognition rules will aid in mapping MTM sites across different promoters towards development of MTM analogues as useful anticancer agents.

Keywords: DNA binding, Natural product, Minor groove, Anticancer agent, Metal ion coordination

1. Introduction

After its discovery in 1960, an aureolic acid natural product mithramycin (MTM; Fig. 1) was initially used in the treatment of Paget's disease [1–3] and disseminated testicular carcinoma [3]. Due to toxicity of MTM, its more recent clinical use has been limited to treatment of hypercalcemia associated with cancers. Interest in MTM was renewed after it was identified by high-throughput screening of 50,000 compounds and then validated as a potent antagonist of the oncogenic transcription factor EWS-FLI1 (Ewing sarcoma–Friend Leukemia Integration 1) [4]. EWS-FLI1 is a principal driver of Ewing sarcoma [5], a rare devastating bone cancer affecting primarily children and young adults. MTM displayed potent cytotoxic and anti-tumor activities in xenograft models of Ewing sarcoma in mice [4], owing to its action as an EWS-FLI1 inhibitor. On the basis of these findings, MTM recently entered clinical trials as a novel Ewing sarcoma chemotherapeutic (National Cancer Institute, clinical trial NCT01610570).

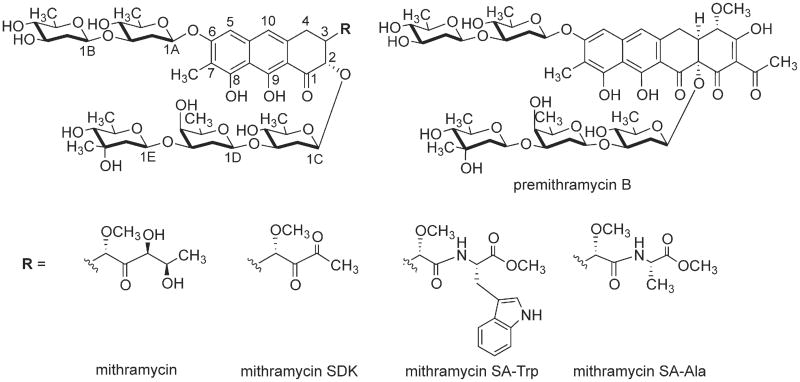

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of MTM, its analogues MTM SDK, MTM SA-Trp, MTM SA-Ala and PreMTM B.

Aureolic acid natural products bind in the minor groove of GC-rich DNA, thereby disrupting transcription of protooncogenes [6–14]. MTM binding was shown to lead to structural changes in DNA that were consistent with the widening of the minor groove [15,16]. MTM and other known aureolic acid compounds, except chromocylomycin, consist of a tricyclic polyketide-derived aglycone with two oligosaccharide chains at C-2 and C-6 positions of the aglycone and two aliphatic side chains, branching off at C-3 and C-7 (Fig. 1). Combinatorial biosynthetic and semisynthetic approaches yielded several MTM analogues including MTM SDK (for Short side chain, DiKeto) [17], MTM SK (for Short side chain, Keto), MTM SA (for Short side chain, Acid) [18], and MTM SA-amino acid residue derivatives (Fig. 1) [19]. Genetic engineering of the MTM-producing bacterium Streptomyces argillaceus to inactivate the gene mtmW encoding the enzyme catalyzing the final step of the MTM biosynthetic pathway, the ketoreductase MtmW, yielded derivatives MTM SA, MTM SK [18], and MTM SDK [17]. These MTM analogues all contained shortened 3-side chains, which had been shown by previous NMR studies of MTM [20,21] to interact with the sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA. Both MTM SK [18] and MTM SDK [17] displayed higher potency against several human cancer cell lines and lower toxicity than those of MTM, demonstrating that 3-side chain modifications can modulate activity of MTM analogues. MTM SA had a decreased cytotoxicity [18] but the carboxylic moiety provided a chemical handle that could be readily and selectively modified to further diversify this analogue towards derivatives with increased activity. The amino acid residue derivatives of MTM SA contained glycine, valine, cysteine, and alanine residues, of which MTM SA-Ala was the most promising, although still not as potent as MTM SK or MTM SDK against a human non-small cell lung cancer cell line A549 [19]. Consequently, additional MTM SA amino acid derivatives have been generated including the most promising MTM SA-Trp, which we present here for the first time.

MTM binds DNA as a dimer, in which the O-1 carbonyl and the O-9 enolate anion of the aglycone of each monomer are coordinated via a divalent metal ion (Me2+) [22,23]. DNase I footprinting studies of MTM bound to DNA showed that MTM protects three base pair sites, with a preference to sites containing GG dinucleotide steps [24]. Pioneering solution NMR studies revealed that the MTM2-Me2+ binds a palindromic DNA oligomer containing the sequence GGCC, where the 2-fold rotational symmetry of the MTM dimer coincides with the symmetry of the palindromic DNA [20,21]. These structures indicated that the C-8 hydroxyl groups on the chromophores of each MTM monomer form hydrogen bonds with the NH2 group of the central guanine bases on the complementary strands, while the flexible saccharide chains of the two MTM monomers are extended along the minor groove of the DNA in a symmetric antiparallel fashion. A crystal structure of chromomycin A3 (CHR), a related natural product containing the same aglycone core as MTM, in complex with a GGCC-containing DNA was consistent with the solution structure of MTM-DNA complex, showing additionally the octahedral coordination of the divalent metal ion and the widened minor groove of the DNA [25]. These structural studies, in agreement with DNA binding studies in solution, demonstrated that the DNA binding sites for MTM and CHR were four base pairs long.

The rules for DNA sequence recognition of MTM are still not fully understood. For example, whether MTM recognizes a specific DNA sequence (direct readout), DNA conformation (indirect readout) or both, is not clear [26]. MTM preferentially binds G/C-rich sequences [24,27–29]. Binding to a GC sequence is strengthened by flanking TA steps, and a GC site is preferred over a CG site [24,28,30]. DNase I footprinting using DNA fragments containing all 64 symmetrical hexanucleotide sequences demonstrated that MTM binds best to AGCGCT and GGGCCC [29]. However, this study also showed that MTM also bound well at non-GC sites, such as ACCGGT. While these studies systematically investigated sequences at which MTM is footprintable, other sequences that form thermodynamically stable, but relatively short-lived complexes with MTM may have eluded detection, leaving open the question of the minimum DNA recognition sequence of MTM.

In this study we performed equilibrium titrations at a physiologically relevant salt concentration, to investigate the propensity of MTM and its novel analogues to dimerize and recognize DNA of different sequences and conformations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Benzotriazol-1-yl-oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP), L-tryptophan methyl ester hydrochloride, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), dichloromethane (DCM), hepes, magnesium chloride hexahydrate, iron (II) chloride and sodium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Methanol (MeOH), acetonitrile (ACN), celite, C18 reverse phase silica gel, tryptic soy broth (TSB), Luria–Bertani broth (LB), Difco agar, sucrose, potassium sulfate, glucose, casamino acids, yeast extract, MOPS, and trace elements were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Methanol-d4 was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). S. argillaceus ATCC 12956 was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). DNA oligomers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (IDT) (Coralville, IA). Microtiter plates were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). MTM, MTM SDK, PreMTM B, and MTM SA Ala, were produced by previously reported procedures [17,19,31].

2.2. Semisynthetic generation of MTM SA-Trp

MTM SA-Trp was synthesized by chemical modification of MTM SA, which was produced by a procedure reported previously [32]. MTM SA-Trp was synthesized by coupling L-tryptophan methyl ester to the C-3 side chain of MTM SA. The L-tryptophan used in this study possesses an additional methyl group to protect the carboxylic group in order to increase the coupling efficiency and the yield of the product. After optimizing reaction conditions, we found PyBOP to be the most efficient catalyst for this coupling reaction. DIPEA could efficiently deprotonate the terminal carboxylic acid group of MTM SA. The reaction was carried out by stirring after mixing 10 mg MTM SA was mixed with 3 equivalents of l-tryptophan methyl ester hydrochloride, 3 equivalents of DIPEA, 2 equivalents of PyBOP in DCM as a solvent for 16 h at 4 °C. The produced MTM SA-Trp was analyzed by LC-MS. After the reaction was completed, we removed the organic solvent and re-dissolved the dried sample in MeOH. MTM SA-Trp was purified by silica gel column chromatography. The silica gel column was equilibrated in 100% DCM, the sample was loaded and eluted with MeOH (in DCM) by a gradient from 5% to 65% MeOH, followed by 100% MeOH. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was used to identify which fractions contained MTM SA-Trp. After combining these fractions and removing the organic solvent, we purified MTM SA-Trp with semi-preparative HPLC (Waters HPLC system). An elution gradient from solvent A (2% formic acid in water) to solvent B (100% acetonitrile) was used in this step. Fraction of solvent B was increased from 25% to 70% in the first 19 min, from 70% to 90% in the next 2 min, from 90% to 100% in the next 2 min and then maintained at 100% for 8 min. Then fraction of B was lowered to 25% within 2 min and kept at 25% for the last 2.5 min. The yield of pure MTM SA-Trp was 10–15%.

2.3. Dimerization assays

Concentrations of MTM, its analogues and Pre MTM B were determined by measurements based on the dry material mass. The concentrations of MTM and its analogues were consistent with the measurements of absorbance at 400 nm using a Thermo Scientific Biomate 3S spectrophotometer assuming the molar extinction coefficient of 10,000 M−1 cm−1. The dimerization assays were carried out in 40 mM Hepes pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, by titrating MgCl2 into a solution of MTM or analogue at constant concentration at 21 °C. The concentrations of MTM, MTM SDK, Pre MTM B, MTM SA-Trp, and MTM SA-Ala were 1 μM, 5 μM or 10 μM, as specified in the text. The dimers were more stable in Fe2+ than in Mg2+; therefore, lower concentrations of the divalent metal ion were used, as specified. Fluorescence of MTM and its analogues, generated for the excitation wavelength of 470 nm and emission wavelength of 540 nm, was measured on a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.4. Analysis of the dimerization assay data

MTM dimerization is mediated by one divalent metal ion cooperatively [33]:

| (1) |

where M designates a monomer of MTM, and Me2+ is the divalent metal ion. The equilibrium constant for this process in the direction of dissociation is

| (2) |

Conservation of material for mithramycin is given by the following expression:

| (3) |

where is the total concentration of mithramycin in the mixture.

Solving the system of Eqs. (2) and (3) for [M] and [M2·Me2+] yields:

| (4) |

| (5) |

Finally, the observed fluorescence is a sum of contributions from M and M2·Me2+ species:

| (6) |

where C1 and C2 are molar fluorescence yield of M and M2·Me2+, respectively, and C3 is the signal in the absence of MTM. Nonlinear regression using SigmaPlot (SysStat) was employed to obtain best-fit values of Kd by fitting Eq. (6) to the data for MTM and its analogues.

2.5. DNA binding assays and data analysis

DNA oligomers of the palindromic sequences reported in the text were dissolved in 10 mM Na cacodylate buffer pH 6.0 to a final concentration of 2 mM. DNA was self-annealed in the annealing buffer (10 mM Na cacodylate, pH 6.0, 50 mM NaCl) by heating to 95 °C for 5 min and cooling for 30 min to 4 °C. The DNA concentrations were then calculated based on the respective extinction coefficients for double-stranded DNA by the IDT online concentration calculation tool [34]. The same tool was used to calculate the DNA melting temperatures [35].

The DNA binding assays were carried out in 40 mM Hepes pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2 at 21 °C, where the majority of MTM or its analogue is in the dimeric form. DNA was titrated into MTM or its analogues, where all compounds were used at the concentrations specified in the text. Fluorescence was measured as it was in the dimerization assays. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

The DNA melting experiment for oligomer GGTTAACC (at 6 μM in single strands) was carried out by measuring absorbance at 260 nm at temperatures increasing from 8 °C to 50 °C over 1 h in the binding buffer. These data were collected on a Shimadzu spectrophotometer TCC-240A UV-1800 equipped with a temperature-controlled cell holder.

Binding of an MTM dimer to a short DNA oligomer is described by the following 1:1 binding equilibrium:

| (7) |

where D and M2·Me2·D denote free DNA and MTM-DNA complex, respectively. The equilibrium constant KDNA in the direction of dissociation is

| (8) |

The equations describing conservation of D and M are:

| (9) |

| (10) |

Eqs. (8)–(10) yield [M2·Me2] and [M2·Me2·D]:

| (11) |

| (12) |

and

| (13) |

As in the dimerization assay, the fluorescence signal is a sum of contributions from M2•Me2+ and M2·Me2·D:

| (14) |

where C2 and C3 were defined previously and C4 is the molar fluorescence of MTM-DNA complex. Nonlinear regression curve fitting to the titration data with SigmaPlot was used to obtain the values of Kd.

The structural parameters of DNA were calculated from the crystal structure coordinates by using 3DNA software [36].

2.6. NMR spectroscopy

1H, gHSQC, and gHMBC spectra were recorded using Varian Inova 500 spectrometer at a magnetic field strength of B0 11.74 T (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Chemical shifts are given in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS). J values are recorded in Hz. A photodiode array detector (Waters 2996) along with a Micromass ZQ 2000 mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) probe was used to detect the molecular ions and identify the compounds. HR-MALDI-TOF-MS analysis was carried out by MS facilities at University of Kentucky.

3. Results and discussion

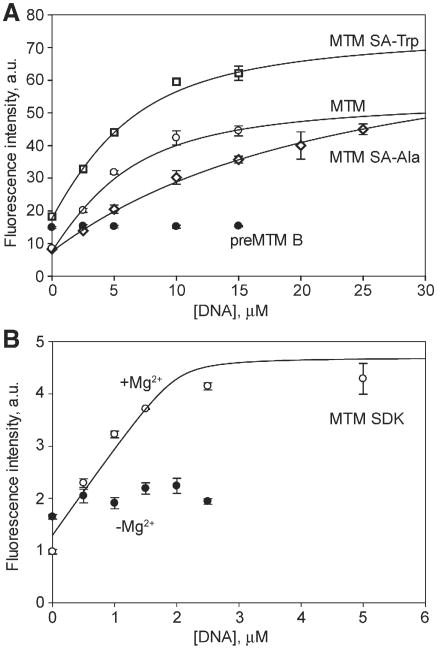

3.1. Dimerization of MTM and its analogues

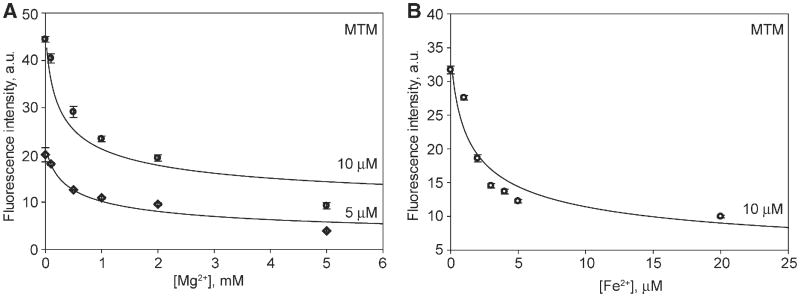

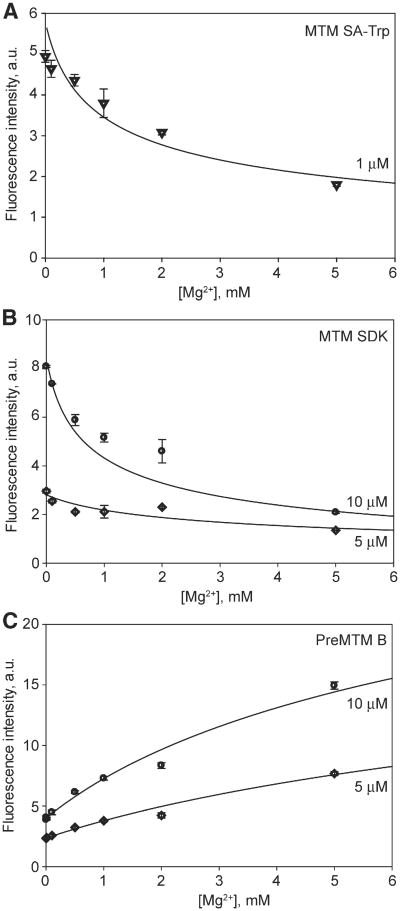

Whether MTM is a monomer or a dimer when free in solution at physiological salt concentrations is an open question, since previous dimerization studies of MTM dimerization, although rigorous, have been performed at non-physiologically relevant salt concentrations [33,37,38]. We investigated the effect of Mg2+ concentration on the dimer stability of MTM and its analogues at 100 mM NaCl, i.e. at a physiologically relevant concentration of monovalent cations, by monitoring the change of intrinsic fluorescence of MTM (Fig. 2) and its analogues (Fig. 3), including a novel analogue MTM SA-Trp, upon their dimerization. The fluorescence of MTM and all analogues, except PreMTM B (Fig. 3C), was quenched upon dimerization with increasing concentration of Mg2+. The chromophore of PreMTM B is tetracyclic; therefore, the observed increase of its fluorescence may arise from a different orientation of the two chromophores in a PreMTM B dimer from that in MTM. These data were in good agreement with the cooperative 2MTM:Me2+ binding model, which yielded best-fit values of the equilibrium dimerization constants Kd (Table 1). MTM and MTM SA-Trp exhibited a similar propensity to dimerize, stronger than that of MTM SDK and PreMTM B. PreMTM B was by far the most defective in dimer formation, with a 40-fold higher Kd than that of MTM. For MTM and MTM SDK at 5 mM Mg2+ these Kd values correspond to the values of the apparent dimerization equilibrium constant (for the process 2 M ⇌ M2) of 0.7 μM and 2.8 μM, respectively. These values indicate that at 5 μM or higher concentrations, MTM and MTM SDK are dimeric at these conditions at 5 mM Mg2+ and 100 mM NaCl, i.e. in the physiological range of salt concentrations. In contrast, PreMTM B is mostly dimeric only at ∼30 μM and higher concentrations. Indeed, the fluorescence intensity reaches a plateau by 5 mM Mg2+ for MTM and MTM SDK, but not for PreMTM B (Fig. 2). In addition, we also tested the effect of Fe2+ on MTM dimerization. In agreement with a previous report [38], Fe2+ is a more potent MTM dimerizer, with Kd at least 100-fold smaller than in Mg2+ (Table 1). MTM SA-Ala was prone to aggregation in the absence of divalent metal ions yielding an unstable signal. Nevertheless, MTM SA-Ala formed dimers as well, as described in Section 3.2.

Fig. 2.

Divalent metal ion-dependent dimerization of MTM observed through quenching of intrinsic MTM fluorescence. A. Mg2+-dependent dimerization of MTM. B. Fe2+-dependent dimerization of MTM. The curves correspond to the cooperative dimerization model given by Eq. (1) with the best-fit parameter values in Table 1. The concentrations of MTM in each titration are indicated.

Fig. 3.

Mg2+-dependent dimerization of MTM analogues: MTM SA-Trp (panel A), MTM SDK (panel B) and Pre MTM B (panel C) at specified concentrations.

Table 1.

Equilibrium dimerization constants for MTM and its analogues.

| MTM analogue | Metal ion | Kd, (μM)2 |

|---|---|---|

| MTM | Mg2+ | (3.6 ± 1.7) × 103 |

| MTM | Fe2+ | <40a |

| MTM SA-Trp | Mg2+ | (1.8 ± 0.9) × 103 |

| MTM SDK | Mg2+ | (13.9 ± 4.0) × 103 |

| PreMTM B | Mg2+ | (120 ± 70) × 103 |

Only an upper bound could be determined from the data.

3.2. DNA binding by MTM and its analogues

In order to define DNA sequence and conformational specificity determinants for binding MTM, we chose 13 palindromic 8-mer DNA sequences (Table 2). Crystal structures of respective double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides covering the entire sequence or a relevant part of it were previously determined. These sequences comprised B- and A-form DNA and included a sequence containing a well-established MTM binding motif GGCC that was used in the solution NMR studies of MTM-DNA complex [20,21]. Among B-form DNA, we included G/C-rich oligomers as well as oligomers with a widened minor groove. The length of 8 base pairs was chosen to minimize the potential of binding of multiple MTM dimers to a single DNA oligomer; shorter DNA would have a compromised duplex stability. Binding of MTM and its analogues to these DNA oligonucleotides was studied at salt concentrations close to physiological, where the dominant species are dimers, as established by the studies described in the previous section. Furthermore, at these salt concentrations and assay temperature (21 °C), the DNA oligomers are predominantly in the double-stranded form. The calculated DNA melting temperatures at these conditions at 6 μM of each oligomer, or 3 μM of double-stranded oligomer, which is approximately the lowest DNA concentration used in the titrations, range from 28 °C for CTCTAGAG to 59 °C for CGGCGCCG [35]. Even though the melting temperatures calculated by this method were shown to be accurate for 8-mer and larger oligomers [35], we carried out a DNA melting experiment with oligomer GGTTAACC (at 3 μMin terms of duplexes) with one of the lowest calculated melting temperatures of 32.2 °C. In this experiment we monitored the hyperchromic effect by measuring absorbance at 260 nm as a function of gradually increasing temperature. The observed melting curve (Supplementary Fig. S5) yielded the melting temperature of ∼32 °C, in excellent agreement with the calculation. These data also demonstrate that at the assay temperature of 21 °C this DNA oligomer is in the double-stranded state.

Table 2.

Structural and MTM analogue binding characteristics of the DNA oligomers.

| DNA | Analogue | DNA form | PDB IDa | Average Zpb (Å) | Minor groove width (Å) | Major groove width (Å) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGGCGCCG | MTM | B | 1CGC | −0.1 | 12.8 | 16.5 | <1c |

| CCCCGGGG | MTM | A | 187D | 2.5 | 15.4 | 15.1 | <1 |

| GGGATCCC | MTM | A | 3ANA | 2.4 | 16.1 | 16.0 | <1 |

| GGGTACCC | MTM | A | 1VT9 | 2.5 | 16.4 | 15.3 | <1 |

| AGGTACCT | MTM | B | 1SS7 | 0.03 | 12.8 | 16.1 | <1 |

| GTAGCTAC | MTM | B | 141D | 0.0 | 13.2 | 21.2 | <1 |

| GATCGATC | MTM | B | 1D23 | −0.1 | 12.2 | 17.3 | <1 |

| GAGGCCTC | MTM | B | 1BD1 | −0.6 | 11.7 | 17.3 | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| GTACGTAC | MTM | A | 28DN | 2.4 | 15.2 | 16.4 | 7.8 ± 0.3 |

| GTGTACAC | MTM | A | 1D78 | 1.9 | 17.0 | 13.4 | 13 ± 1 |

| GGAATTCC | MTM | B | 1SGS | −0.7 | 12.2 | 18.0 | 59 ± 2 |

| GTCTAGAC | MTM | A | 1D82 | 2.1 | 15.5 | 16.2 | 25 ± 1 |

| CTCTAGAG | MTM | A | 1D93 | 2.1 | 15.4 | 15.6 | 82 ± 9 |

| CGGCGCCG | MTM SA-Trp | See above | 1.2 ± 0.2 | ||||

| GAGGCCTC | MTM SA-Trp | 2.1 ± 0.3 | |||||

| CCCCGGGG | MTM SA-Trp | 2.1 ± 0.6 | |||||

| GGGTACCC | MTM SA-Trp | 3.7 ± 1.5 | |||||

| GGGATCCC | MTM SA-Trp | 4.3 ± 1.5 | |||||

| GAGGCCTC | MTM SDK | <1 | |||||

| GAGGCCTC | MTM SA-Ala | 19.6 ± 3.8 | |||||

| GAGGCCTC | PreMTM B | >300 |

The crystal structures were previously published as follows: 1CGC [44], 187D [45], 3ANA [46], 1VT9 [47], 1SS7 [48], 141D [49], 1D23 [50], 1BD1 [42], 28DN [51], 1D78 [51], 1SGS [52], 1D82 [53], and 1D93 [54].

Zp, a difference between coordinates of projections of the two phosphorus atoms of a base pair onto the DNA helical axis, was averaged ether among all base pairs or for those that constituted a binding site (a stretch of two or more (G/C) base pairs), where such stretch was present.

The upper bound on Kd of ∼1 μM was defined by the detection limit of the assay.

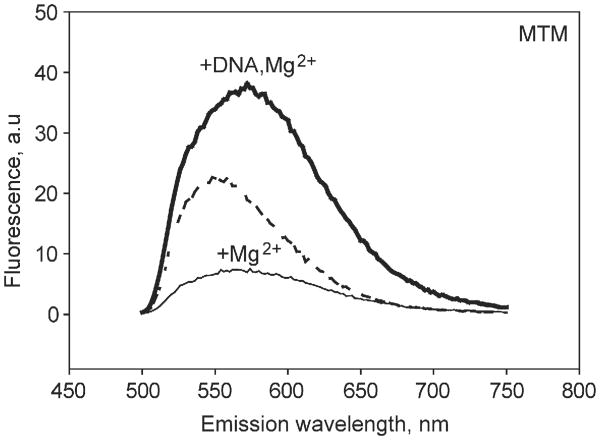

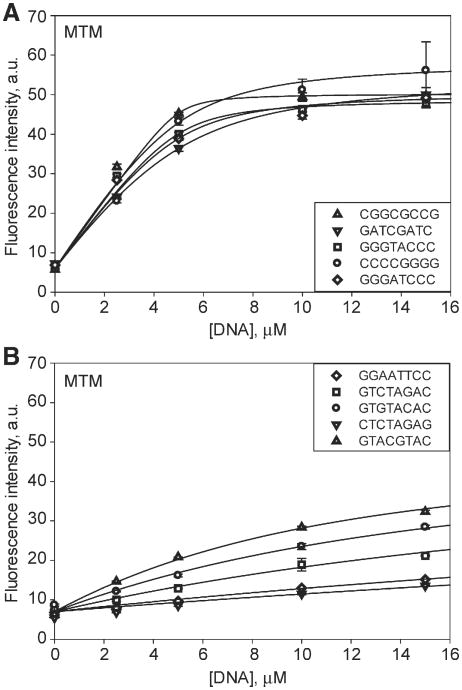

Strong MTM-DNA binding resulted in an ∼8-fold increase of fluorescence intensity at the fluorescence maximum (Fig. 4), apparently due to unquenching of the chromophore rings. Such unquenching may occur upon reorientation of the MTM molecules in the dimer upon DNA binding. Fluorescence enhancement upon MTM binding to DNA was observed previously [39]. These and the other DNA titration data fit well to a 1:1 binding isotherm. The best-fit Kd values for all titrations and the DNA structural parameters are given in Table 2. Affinities stronger than 1 μM could not be measured and were indicated as bounds in Table 2, because of the low fluorescence signal at concentrations of MTM and analogues required for such measurements.

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence emission spectra of MTM (10 μM) in the absence of divalent metal and DNA (the dashed line), with 5 mM MgCl2 and no DNA (the thin solid line), and with 5 mM MgCl2 and 10 μM GAGGCCTC DNA (the thick solid line). The excitation wavelength was 470 nm.

Binding of MTM to DNA was tested most extensively, with all 13 DNA oligomers; binding of the novel analogue, MTM SA-Trp was tested with 5 oligomers and binding of MTM SDK and PreMTM B was tested with one oligomer, GAGGCCTC, which was tested with all the compounds. Representative titration data for MTM with high-affinity and low-affinity oligomers are shown in Fig. 5A and B, respectively. The strongest MTM-DNA binding affinity was observed for 8 DNA oligomers, with Kd values of 2 μM or smaller. All of these sequences contain at least one GG, GC, CG or CC site (note that a CC sequence is automatically present if a GG sequence is present due to complementarity). Notably, sequence GGAATTCC containing a terminal GG site did not bind MTM well (Kd = 59 μM). On the other hand, sequence AGGTACCT was a high-affinity sequence. These results indicate that a binding site needs to contain at least one flanking base pair on each side. MTM displayed low affinity for all sequences that did not contain an internal GG, GC or CG site. Therefore, 2-base pair sequences GG (CC), GC and CG that are flanked by at least one base pair on each side are preferred sequences for binding MTM, whereas the other 2-base pair sequences are non-preferred. In other words, the minimum DNA recognition sequence for MTM is a 4-base pair sequence X(G/C)(G/C)X, where either G or C in any order, and X is any base.

Fig. 5.

Binding of MTM (10 μM) to double-stranded DNA oligomers of different sequences. A. Representative titrations of MTM with high-affinity DNA oligomers. B. Representative titrations of MTM with low-affinity DNA oligomers. The curves are the best fit to the 1:1 binding model with the values given in Table 2. The DNA sequences are specified in the inset.

Binding affinity to the high-affinity sequences was modulated by the base pairs flanking the GG/GC/CG site. Sequence GATCGATC bound MTM with at least a 7-fold higher affinity than did GTACGTAC. This effect of flanking sequences is consistent with previous observations [40]. Sequence GTAGCTAC, containing a GC in place of the CG in the same context, was a high affinity sequence, reversing the effect of the flanking DNA, in agreement with a previous study showing a preference of MTM for an isolated GC over an isolated CG site [40]. These results suggest that the conformation or position of an MTM dimer bound to a GC site differ somewhat from that bound to a CG site, resulting in different interactions with flanking DNA. Structural investigation of this adaptability of MTM binding different sequences is in progress.

Next we examined whether DNA affinity of MTM was additionally defined by or correlated with DNA structural parameters (Table 2). Because aureolic acid natural products were shown to bind in the minor groove, we focused on the geometric parameters of the minor and major grooves of the DNA oligomers of interest, as calculated by 3DNA software [36]. Binding of MTM did not appear to be correlated with any of the structural parameters: the conformation of the DNA backbone (B- vs. A-form), the Zp values, or the widths of the minor and the major grooves. These observations are consistent with a previous study demonstrating strong binding to two G/C rich sequences, one Band the other A-form [41]. Nevertheless, because the best MTM binding sequences were somewhat enriched in G/C stretches, which are known to have a widened minor groove [42,43], this effect of intrinsic sequence-dependent minor groove widening on MTM binding cannot be further uncoupled from the (G/C)(G/C) sequence recognition, at least with naturally occurring nucleotides.

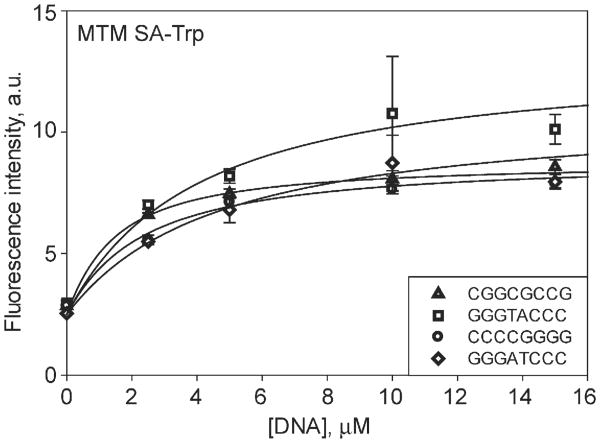

We next tested whether modifications at position 3 had an effect on DNA binding. DNA binding of the novel analogue, MTM SA-Trp, was measured with 5 oligomers that displayed high affinity towards MTM (Table 2, Fig. 6). MTM SA-Trp exhibited Kd values in the range 1–4 μM. Thus the DNA affinities of MTM SA-Trp were either similar or some what weaker than those of MTM. Sequence GAGGCCTC bound with a similar affinity (Kd = 2 μM) to MTM and MTM SA-Trp (Table 2, Fig. 7A). Additionally, binding of the other analogues, MTM SDK, MTM SA-Ala and PreMTM B, to a strong binding sequence GAGGCCTC was measured (Table 2, Fig. 7A and B). MTM SDK bound the DNA at least 2-fold more tightly than did MTM, possibly due to reduced steric hindrance by the shorter side chain of MTM SDK. To check whether MTM SDK binding to DNA was still Mg2+-mediated and was not due to a new binding mode that became possible because of its specific side chain, we performed the same titration in the absence of Mg2+ with this analogue (Fig. 7B). No binding was observed, indicating that the binding mode was unchanged by the side chain modification. Interestingly MTM SA-Ala bound ∼10-fold more weakly than MTM did, apparently due to the unfavorable environment of the Ala methyl group. PreMTM B did not display any observable binding, indicating that this tetracyclic scaffold cannot adapt the same way to the features of the minor groove.

Fig. 6.

Binding of MTM SA-Trp (1 μM) to double-stranded DNA oligomers of different high-affinity sequences, as indicated in the inset.

Fig. 7.

Binding of MTM and its analogues to GAGGCCTC DNA. A. Binding of MTM, MTM SA-Trp, MTM SA-Ala and PreMTM B, each at 10 μM. B. Binding of MTM SDK (4 μM) in the presence (open circles) and in the absence (filled circles) of Mg2+.

3.3. Elucidation of the chemical structure of MTM SA-Trp

The structure of MTM SA-Trp (Fig. 1) was confirmed by HR-MS and NMR. The signals of L-tryptophan methyl ester were observed by 1D and 2D NMR (Table 3 and Supplementary Figs. S1–S3). Indicative are the indole unit signals at δ 7.06 7.21, 7.43 and 7.66, respectively, observed in the 1H NMR spectrum, as well as a second OCH3 signal of the 3-side chain at δ 3.81, as well as the 4′-H multiplet signal at d 4.95–5.02, which couples to both carbonyl groups in the HMBC spectrum. The observed molecular weight of the sample (1249.5181) matched the calculated molecular weight of MTM SA-Trp ([C61H82N2O24Na]+ = 1249.5155) (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Table 3.

NMR (B0 = 11.74 T) data on MTM SA-Trpa.

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δCb, multiplicity | HMBC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (203.5, C)c | ||

| 2 | 4.43, d (11.5) | 77.4, CH | 44.6, 102.1 |

| 3 | 2.29, d (13.0) | 44.6, CH | |

| 4 | 1.73–1.98 (m, 5 H) 2.32–2.42 (m, 1 H) | 27.2, CH2 | 77.4, 80.8, 117.9, 135.9 |

| 4a | 135.9, C | ||

| 5 | 6.56, s | 101.7, CH | 108.2, 111.3, 117.9, 159.6 |

| 6 | 159.6, C | ||

| 7 | 111.3, C | ||

| 7-CH3 | 2.14, s | 8.7, CH3 | 111.3, 156.4, 159.6 |

| 8 | 156.4, C | ||

| 8a | 108.2, C | ||

| 9 | (164.5, C)d | ||

| 9a | 102.1, C | ||

| 10 | 5.93, s | 117.9, CH | 27.2, 101.7, 108.2, 139.1 |

| 10a | 139.1, C | ||

| 1′ | 4.06, s | 80.8, CH | 27.2, 44.6, 59.9, 77.4, 173.9 |

| 1′-OCH3 | 3.47, s | 59.9, CH3 | 80.8 |

| 2′ | 173.9, C | ||

| 4′ | 4.95–5.02 (m, complex) | 53.1, CH | 173.2, 173.9 |

| 5′ | 173.2, C | ||

| 5′-OCH3 | 3.81, s | 52.8, CH3 | 173.2 |

| 2″ | 7.21, s (overlap) | 124.1, CH | 110.9, 112.3, 119.3, 128.5, 137.8 |

| 3″ | 110.9, C | ||

| 3″a | 128.5, C | ||

| 4″ | 7.66, d (7.5) | 119.3, CH | 110.9, 112.3, 122.7, 128.5, 137.8 |

| 5″ | 7.21, t (7.5) (overlap) | 122.7, CH | 110.9, 112.3, 119.3, 128.5, 137.8 |

| 6″ | 7.06, t (7.5) | 119.9, CH | 110.9, 112.3, 124.1, 128.5, 137.8 |

| 7″ | 7.43, d (8.0) | 112.3, CH | 119.9, 124.1, 128.5 |

| 7″a | 137.8, C | ||

| 8″ | 3.37–3.43 (m, 2 H) 3.50, dd (4.3, 15.3) | 28.0, CH2 | 53.1, 110.9, 124.1, 128.5 53.1, 110.9, 124.1, 128.5 |

| 1A | 5.32, d (9.0) | 97.7, CH | |

| 2A | 1.73–1.98 (m, 5 H) 2.48, dd (4.0, 10.5) | 37.9, CH2 | 97.7 76.0, 80.3 |

| 3A | 3.65–3.78 (m, 4 H) | 80.3, CH | |

| 4A | 3.04, t (9.0) | 76.0, CH | 18.2, 73.2, 80.3 |

| 5A | 3.32–3.34 (m, 1 H) | 73.2, CH | |

| 6A | 1.44, d (6.0) | 18.2, CH3 | 73.2, 76.0 |

| 1B | 4.65, dd (1.5, 9.5) | 99.7, CH | 80.3 |

| 2B | 1.50–1.66 (m, 3 H) 2.22 (m, 1 H) | 40.4, CH2 | 71.4, 99.7 71.4, 77.8, 99.7 |

| 3B | 3.65–3.78 (m, 4 H) | 71.4, CH | 77.8 |

| 4B | 2.98, t (9.0) | 77.8, CH | 17.6, 71.4, 73.2 |

| 5B | 3.65–3.78 (m, 4 H) | 73.2, CH | |

| 6B | 1.31–1.37 (m, 6 H) | 17.6, CH3 | 73.2, 77.8 |

| 1C | 5.04, d (9.5) | 101.8, CH | |

| 2C | 1.50–1.66 (m, 3 H) 2.56, dd (4.0, 11.0) | 37.9, CH2 | 80.5, 101.8 76.0, 80.5, 101.8 |

| 3C | 3.83–3.93 (m, 2 H) | 80.5, CH | 76.0 |

| 4C | 3.14, t (8.8) | 76.0, CH | 18.2, 73.4, 80.5 |

| 5C | 3.37–3.43 (m, 2 H) | 73.4, CH | |

| 6C | 1.31–1.37 (m, 6 H) | 18.2, CH3 | 73.2, 76.0 |

| 1D | 4.78, dd (1.0, 9.5) | 100.0, CH | 80.5 |

| 2D | 1.73–1.98 (m, 5 H) 1.73–1.98 (m, 5 H) | 33.0, CH2 | 77.0, 100.0 70.2, 77.0, 100.0 |

| 3D | 3.83–3.93 (m, 2 H) | 77.0, CH | 100.0 |

| 4D | 3.65–3.78 (m, 4 H) | 70.2, CH | 77.0 |

| 5D | 3.54–3.64 (m, 3 H) | 71.4, CH | 16.8, 70.2 |

| 6D | 1.29, d (6.5) | 16.8, CH3 | 70.2, 71.4 |

| 1E | 4.95–5.02 (m, 2 H) | 98.8, CH | 27.5, 44.8, 77.0 |

| 2E | 1.50–1.66 (m, 3 H) 1.73–1.98 (m, 5 H) | 44.8, CH2 | 71.4, 98.8 71.4, 77.4, 98.8 |

| 3E | 70.0, C | ||

| 3E-CH3 | 1.24, s | 27.5, CH3 | 44.8, 71.4, 77.4, 98.8 |

| 4E | 2.92, d (9.5) | 77.8, CH | 18.2, 71.4 |

| 5E | 3.54–3.64 (m, 3 H) | 71.4, CH | 70.0, 98.8 |

| 6E | 1.26, d (6.5) | 18.2, CH3 | 77.8, 71.4 |

The solvent used for NMR experiments was methanol-d4.

13C NMR data was inferred from gHSQC and gHMBC spectra.

The numbers in the parentheses are based on previously published mithramycin data [19].

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study exploited the intrinsic MTM fluorescence to interrogate the dimerization and DNA binding properties of MTM and its analogues. We obtained the minimum DNA binding requirements for MTM and established that it is the direct (sequence) and not indirect (conformation) read-out that guides DNA recognition by MTM. The 3-side chain derivatization led to modulation of DNA binding affinity of the analogues. Future studies will characterize structural details of binding of MTM and its analogues to different DNA sequences and use the DNA recognition rules established here to map MTM binding sites in oncogenic promoters and other regulatory sites in the genome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health CA091901 and GM105977 (to J.R.) and by a Markey Cancer Center Pilot Award.

Abbreviations

- MTM

mithramycin

- PreMTM B

premithramycin B

- MTM SK

mithramycin short side chain, keto

- MTM SDK

mithramycin short side chain, diketo

- MTM SA

mithramycin short side chain, acid

- MTM SA-Trp

mithramycin SA-tryptophan

- MTM SA-Ala

mithramycin SA-alanine

- EWS

Ewing sarcoma

- FLI1

Friend Leukemia Integration 1

- MeOH

methanol

- ACN

acetonitrile

- C18

celite

- TSB

tryptic soy broth

- LB

Luria-Bertani broth

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- HR

high resolution

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight

- MS

mass spectrometry

- ATCC

American Tissue Culture Collection

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.12.011.

Contributor Information

Oleg V. Tsodikov, Email: oleg.tsodikov@uky.edu.

Jürgen Rohr, Email: jrohr2@uky.edu.

References

- 1.Ryan WG, Engl N. J Med. 1970;283:1171. doi: 10.1056/nejm197011192832120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan WG, Schwartz TB, Northrop G. JAMA. 1970;213:1153–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JH, Kennedy BJ. N Engl J Med. 1965;272:111–118. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196501212720301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grohar PJ, Woldemichael GM, Griffin LB, Mendoza A, Chen QR, Yeung C, Currier DG, Davis S, Khanna C, Khan J, McMahon JB, Helman LJ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:962–978. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delattre O, Zucman J, Plougastel B, Desmaze C, Melot T, Peter M, Kovar H, Joubert I, De Jong P, Rouleau G, Aurias A, Thomas G. Nature. 1992;359:162–165. doi: 10.1038/359162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan P, Wang L, Wei D, Zhang J, Jia Z, Li Q, Le X, Wang H, Yao J, Xie K. Cancer. 2007;110:2682–2690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell VW, Davin D, Thomas S, Jones D, Roesel J, Tran-Patterson R, Mayfield CA, Rodu B, Miller DM, Hiramoto RA. Am J Med Sci. 1994;307:167–172. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee TJ, Jung EM, Lee JT, Kim S, Park JW, Choi KS, Kwon TK. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2737–2746. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koutsodontis G, Kardassis D. Oncogene. 2004;23:9190–9200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagashira M, Kitagawa T, Isonishi S, Okamoto A, Ochiai K, Ohtake Y. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:926–929. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha S, Mukherjee S, Mazumdar M, Manna A, Khan P, Adhikary A, Kajal K, Jana D, Sa G, Sarkar DK. T Das, Transl Res. 2015;165:558–577. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulkarni KK, Bankar KG, Shukla RN, Das C, Banerjee A, Dasgupta D, Vasudevan M. Genomics Data. 2015;3:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finotti A, Bianchi N, Fabbri E, Borgatti M, Breveglieri G, Gasparello J, Gambari R. Pharmacol Res. 2015;91:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Guizan A, Mansilla S, Barcelo F, Vizcaino C, Nunez LE, Moris F, Gonzalez S, Portugal J. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;219:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cons BM, Fox KR. FEBS Lett. 1990;264:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80775-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cons BM, Fox KR. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6314–6321. doi: 10.1021/bi00239a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albertini V, Jain A, Vignati S, Napoli S, Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Nur-e-Alam M, Bergant J, Bertoni F, Carbone GM, Rohr J, Catapano CV. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1721–1734. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Remsing LL, Gonzalez AM, Nur-e-Alam M, Fernandez-Lozano MJ, Brana AF, Rix U, Oliveira MA, Mendez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5745–5753. doi: 10.1021/ja034162h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott D, Chen JM, Bae Y. J Rohr, Chem Biol Drug Des. 2013;81:615–624. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sastry M, Fiala R, Patel DJ. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:674–689. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sastry M, Patel DJ. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6588–6604. doi: 10.1021/bi00077a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao XL, Patel DJ. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10940–10956. doi: 10.1021/bi00501a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demicheli C, Albertini JP, Garnier-Suillerot A. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cons BM, Fox KR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5447–5459. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou MH, Robinson H, Gao YG, Wang AH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2214–2222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Sarai A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:376–386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cons BM, Fox KR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160:517–524. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpenter ML, Marks JN, Fox KR. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:561–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hampshire AJ, Fox KR. Biochimie. 2008;90:988–998. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox KR, Howarth NR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8695–8714. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.24.8695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prado L, Fernandez E, Weissbach U, Blanco G, Quiros LM, Brana AF, Mendez C, Rohr J, Salas JA. Chem Biol. 1999;6:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott D, Rohr J, Bae Y. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2757–2767. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu CW, Kuo CF, Chuang SM, Hou MH. Biometals. 2013;26:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10534-012-9589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tataurov AV, You Y, Owczarzy R. Biophys Chem. 2008;133:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owczarzy R, You Y, Moreira BG, Manthey JA, Huang L, Behlke MA, Walder JA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3537–3554. doi: 10.1021/bi034621r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu XJ, Olson WK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–5121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aich P, Dasgupta D. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1376–1385. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou MH, Wang AH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1352–1361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majee S, Sen R, Guha S, Bhattacharyya D, Dasgupta D. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2291–2299. doi: 10.1021/bi9613281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carpenter ML, Cassidy SA, Fox KR. J Mol Recognit. 1994;7:189–197. doi: 10.1002/jmr.300070306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakrabarti S, Bhattacharyya D, Dasgupta D. Biopolymers. 2000;56:85–95. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)56:2<85::AID-BIP1054>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinemann U, Alings C. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:369–381. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodsell DS, Kopka ML, Cascio D, Dickerson RE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2930–2934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinemann U, Alings C, Bansal M. EMBO J. 1931–1939;11:1992. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenstein M, Shakked Z. J Mol Biol. 1995;248:662–678. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauble H, Frank R, Blocker H, Heinemann U. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7799–7816. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenstein M, Frolow F, Shakked Z, Rabinovich D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3185–3194. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McAteer K, Aceves-Gaona A, Michalczyk R, Buchko GW, Isern NG, Silks LA, Miller JH, Kennedy MA. Biopolymers. 2004;75:497–511. doi: 10.1002/bip.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mujeeb A, Kerwin SM, Kenyon GL, James TL. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13419–13431. doi: 10.1021/bi00212a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grzeskowiak K, Yanagi K, Prive GG, Dickerson RE. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8861–8883. doi: 10.2210/pdb1d23/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Courseille C, Dautant A, Hospital M, Langlois D'Estaintot B, Precigoux G, Molko D, Teoule R. Acta Crystallogr A. 1990;46:FC9–FC12. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang DB, Phelps CB, Fusco AJ, Ghosh G. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cervi AR, Destaintot BL, Hunter WN. Acta Crystallogr B. 1992;48:714–719. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hunter WN, D'Estaintot BL, Kennard O. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2444–2451. doi: 10.1021/bi00432a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.