Abstract

Colour constancy is the capacity of visual systems to keep colour perception constant despite changes in the illumination spectrum. Colour constancy has been tested extensively in humans and has also been described in many animals. In humans, colour constancy is often studied quantitatively, but besides humans, this has only been done for the goldfish and the honeybee. In this study, we quantified colour constancy in the chicken by training the birds in a colour discrimination task and testing them in changed illumination spectra to find the largest illumination change in which they were able to remain colour-constant. We used the receptor noise limited model for animal colour vision to quantify the illumination changes, and found that colour constancy performance depended on the difference between the colours used in the discrimination task, the training procedure and the time the chickens were allowed to adapt to a new illumination before making a choice. We analysed literature data on goldfish and honeybee colour constancy with the same method and found that chickens can compensate for larger illumination changes than both. We suggest that future studies on colour constancy in non-human animals could use a similar approach to allow for comparison between species and populations.

Keywords: generalization, vision, visual adaptation, animal colour vision, behaviour, bird vision

1. Introduction

The spectrum of light striking the eyes from an object depends on the reflecting properties of the object and on the spectrum of the illumination. The illumination spectrum changes, globally and locally, over the course of the day, between shaded and sunlit parts of a scene and between habitats, such as a forest or the open field [1,2]. Therefore, the spectrum of light striking the eyes from the same object will also change. Colour constancy is the capacity of the visual system to perceive colours as the same despite changes in illumination spectra [3]. To achieve colour constancy, the visual system must compensate for the illumination change. In humans, at least three processes contribute to colour constancy: one rapid process relying on the influence of the surround on the perception of a focal colour, and a slower process involving adaptation of photoreceptors and other neurons [4,5]. There is evidence for chromatic compensation mechanisms occurring both in the retina and in the cortex [6–8]. Additionally, in humans, memory and cognition play a role in colour constancy, such that familiar objects with a known colour will be perceived as retaining that colour even in changed illuminations [3,9].

Without colour constancy, colour would not provide reliable information, as colour perception would change between different illuminations [3,10]. Colour constancy is thus expected to be present in many animals and has been proven in hawkmoths [11], honeybees [10,12,13], goldfish [14,15], swallowtail butterflies [16], toads [17], non-human primates, chickens and cats [18–20] (as cited by Neumeyer [21]). Most work on animal colour vision assumes colour constancy by adapting receptor sensitivities to the background, and colour vision models typically use a von Kries transformation to account for it [22–25]. While it is common to study human colour constancy with quantitative methods [26,27], most studies on animals have only determined the presence or the absence of colour constancy. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have quantified colour constancy in animals, the honeybee [13] and the goldfish (Carassius auratus) [15].

Narrowly tuned photoreceptor spectral sensitivities, with little or no overlap in sensitivity, are predicted to facilitate colour constancy [28]. The coloured oil droplets in the inner segments of bird cone photoreceptors achieve exactly this tuning; acting as long pass filters, they narrow the spectral sensitivity of the photoreceptors [29,30]. Models of bird colour constancy with and without oil droplets [31] indicate that this may indeed improve colour constancy.

In this study, we quantified bird colour constancy by training chickens to discriminate colours and testing their performance in different illuminations. We aimed to answer four questions: (i) What is the maximum illumination shift in which chickens remain colour-constant? (i) Do larger colour differences between stimuli improve colour constancy? (iii) Does the conditioning procedure affect colour constancy performance? (iv) Does adaptation time affect colour constancy? We describe the shift of the illumination spectrum and colour differences between stimuli with the receptor noise limited (RNL) model [25]. With colour discrimination experiments and psychometric analyses, we determine the largest illumination shifts in which the birds remained colour-constant and relate it to the colour difference between the colours used in the discrimination task. Using this framework will allow quantitative comparison of colour constancy between different species, even with different visual systems.

2. Material and methods

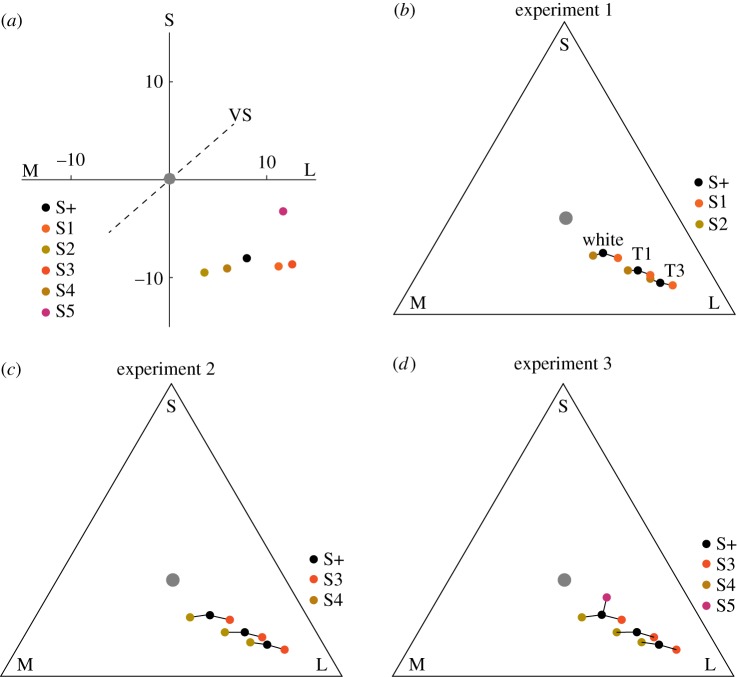

We estimated chicken colour perception and constancy using chromaticity diagrams, in which specific colour coordinates are determined by the relative activation of the receptor types. We used two types of chromaticity diagrams. One is defined by the RNL model where colour distances are measured in just noticeable differences (JNDs), where colour distances more than 1 JND are assumed to be discriminable (see the electronic supplementary material). The second chromaticity diagram that uses only the relative activation of the photoreceptors (see the electronic supplementary material) with distances calculated as Euclidean distances [32] is only used for illustration. For tetrachromatic animals such as the chicken, the chromaticity diagram is a three-dimensional space. The corners of the space represent colours activating only one specific receptor type. We name the photoreceptor types that chickens use for colour vision according to their spectral sensitivity: long-wavelength-sensitive (L, red), medium-wavelength-sensitive (M, green), short-wavelength-sensitive (S, blue) and very-short-wavelength-sensitive (VS, violet). For illustration purposes, we show two-dimensional chromaticity diagrams, where the third dimension, defined by the contribution of the VS channel, which held the smallest signal, extends through the image plane in figure 1a.

Figure 1.

Chromaticity diagrams of the stimuli. S, M and L refer to photoreceptor types, specified in the text. (a) Chromaticity diagram based on the RNL model [25], distances represent JNDs. (b–d) Two-dimensional chromaticity diagrams of the stimuli. The positions of the stimuli are plotted for three illuminations, the white control illumination, T1 and T3. They represent the shift of the colours in the colour spaces assuming absence of colour constancy. The grey point refers to the adapting background, the grey floor of the experimental arena.

All three experiments are based on training chickens to receive food crumbs from coloured food containers (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1), similar to previous studies [33,34]. We trained the birds in white control light to a rewarded colour (S+) appearing orange to humans—we will continue using human colour terms here for an easier description of the conditions. In the first experiment, we used two non-rewarded colours, a redder colour (S1) and a yellower colour (S2) (table 1 and figure 1b). Coloured food containers were always presented in pairs; S+ was presented together with either S1 or S2. This way, the rewarded colour S+ was yellower than the unrewarded colour when presented with S1 and redder when presented with S2, discouraging the use of relative colour learning. After performing control tests in white light, we tested whether the chickens preferred the rewarded colour over either of the unrewarded colours in red-shifted illuminations (figure 2). In the shifted illuminations, assuming no colour constancy, the chickens were expected to be confused and either make random choices, attempt to use relative colour cues or always choose the yellower colour, as this was closest to the locus of the rewarded colour stimulus in training (figure 1). We moved from slightly red-shifted to more strongly red-shifted illuminations to determine the largest illumination shift in which chickens could make this discrimination. The second experiment was similar to the first, but using two unrewarded colours (S3, ‘redder’) and (S4, ‘yellower’) with larger colour differences to S+ (table 1 and figure 1c). This way we tested whether a larger colour difference between the colours improved colour constancy performance and allowed for successful colour discrimination in larger illumination shifts. In the third experiment, we initially used absolute instead of differential training, presenting only the rewarded colour during training and introducing the unrewarded colours only during tests. The aim was to make the experiment more similar to colour constancy tests in humans. Unfortunately, the chickens did not show a strong preference for the rewarded colour after absolute training. Therefore, we continued with differential training using a violet unrewarded colour (S5), with a colour locus in a direction nearly orthogonal to the direction into which we shifted the illumination (figure 1d). We hypothesized that the chickens then would not be able to use any relative information from the training in the test.

Table 1.

Colour difference, double cone quantum catch (QDC) and contrasts between the rewarded and unrewarded stimuli.

| stimulus | colour difference to S+ (JND) | (QDC) | achromatic contrast to S+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| S+ | 0 | 4.05 × 1013 | 0 |

| S1 | 3.16 | 4.20 × 1013 | 0.02 |

| S2 | 2.89 | 4.14 × 1013 | 0.05 |

| S3 | 4.53 | 3.83 × 1013 | 0.02 |

| S4 | 5.34 | 4.33 × 1013 | 0.04 |

| S5 | 11.06 | 3.18 × 1013 | 0.11 |

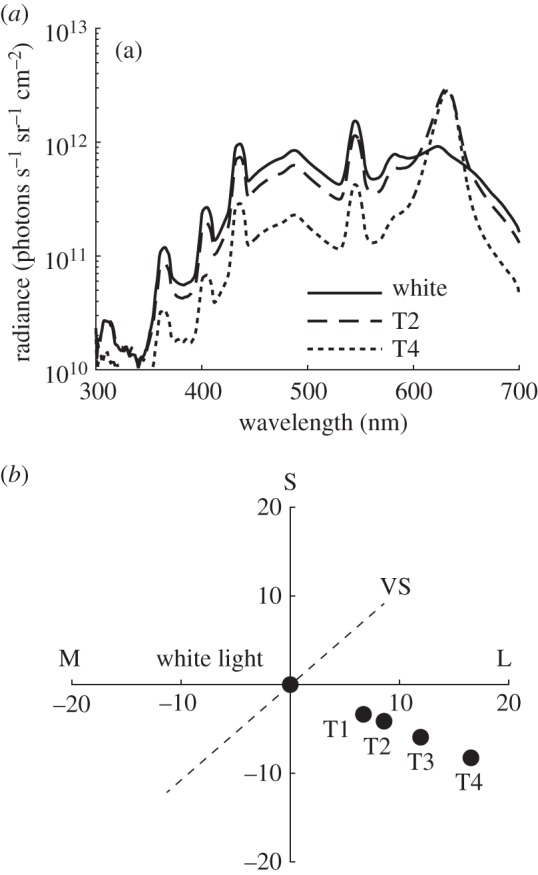

Figure 2.

Illumination spectra and resulting changes in chromaticity. (a) The radiance spectrum of a white standard placed on the floor and measured in three of the illuminations used, for all curves see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3. (b) The illumination shifts in a RNL model chromaticity diagram of all illuminations. T1 is shifted by 7.9, T2 is shifted by 9.9, T3 is shifted by 13.9 and T4 is shifted by 19.1 JNDs from the control illumination.

(a). Animals

Six mixed-breed chickens (Gallus gallus), from a local breeder, and 16 Lohman White chickens (Gimranäs AB, Herrljunga, Sweden) were obtained as eggs, hatched in a commercial incubator (Covatutto 24, Högberga AB, Matfors, Sweden) and kept in 1 × 1 m unpainted wooden boxes, covered by a mesh on top, in groups of six to eight individuals, following ethical approval (permit no. M6–12, Swedish Board of Agriculture). The illumination in the housing is supplied in the electronic supplementary material, figure S2. Water was available ad libitum but availability of food, commercial chick crumbs (Fågel Start, Svenska Foder AB, Staffanstorp), was restricted to training sessions and after the last training session of the day. On days with no training, food was available ad libitum. Both male and female chickens were used in the study, the mixed-breed chickens were used for experiment 1 and the Lohman White chickens were used in experiments 2 and 3.

(b). Experimental arena and illuminations

The experiments were carried out in a wooden arena (0.7 × 0.4 m) painted matte grey. Fluorescent tubes (Biolux L18 W/965, Osram, München, Germany) provided the white illumination (figure 2) used during training and control tests. Two red LEDs (LZ4-00R100, λmax 633 nm, San Jose, CA, USA) controlled by a power supply (CPX200DP, Aim & Thurlby Thandar Instruments, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK) provided red light (figure 2b–e). We created four test illuminations by adjusting the intensities of the two light sources (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, figure S3). We measured the spectral radiance of the illumination as reflected from a white standard placed on the floor of the experimental cage using a spectroradiometer (RSP900-R; International Light, Peabody, MA, USA). The intensity was always high enough (80–300 cd m−2) to allow for chicken colour vision [33].

We calculated natural illumination shifts between a daylight spectrum (sun at 11.4° above the horizon) [2], spectra measured in deciduous and coniferous forest [35], rainforest [36] and own measurements on a cloudy day with the sun at 24° and −3° elevation relative to the horizon measured as the radiance of a white standard placed on the ground with the above-mentioned radiometer (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S4).

(c). Stimuli

Colour stimuli similar to those used in previous studies [33,34] were created in Illustrator CS5 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and printed on copy paper (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). A stimulus consisted of a pattern of 90 tiles, 6 × 2 mm each, forming a rectangle measuring 30 × 36 mm folded into a cone-shaped food container (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Thirty per cent of the tiles were coloured with one of the colours (S+, S1–S5). The intensity of the colour was adjusted by adding a random amount of black ink to each coloured tile. The remaining 70% of the tiles were assigned a random grey intensity with a Michelson contrast, for the double cone, of 0.3 between the highest and lowest intensity grey tile, calculated as

| 2.1 |

Achromatic vision in birds is assumed to be mediated by the double cone [25,37]. The intensity range of the coloured tiles was within the intensity range of the grey tiles. In the control illumination, the achromatic Michelson contrast between S+ and all unrewarding colours used in the tests (S1–S4) was lower than 0.10 (table 1), the achromatic contrast threshold of chickens [38]. The achromatic contrast between S+ and S5 was 0.11, and a weak achromatic signal cannot be excluded, but the very strong chromatic signal should be most salient. Additionally, this colour was used only during training to establish a preference for S+.

(d). Training procedure

Each chicken had two training or testing sessions per day. Training started three days post-hatching. During the first 5 days, we trained the chickens to get used to the stimuli and extracting food from them and to the experimental procedure similar to previous studies [33] (see the electronic supplementary material for details). Each session, from this day onward, consisted of 30 (experiment 1) or 20 (experiments 2 and 3) trials. Tests started after chickens reached a learning criterion of 75% correct choices in two consecutive training sessions.

(e). Behavioural testing procedure

During test sessions, within every block of 10 trials, one randomly chosen trial was completely unrewarded. The remaining 9 out of 10 trials were training trials in the control illumination. The first four test sessions were performed in the control illumination, then we proceeded to the test illuminations. Each new illumination was tested during four sessions, yielding 12 (experiment 1) or eight choices (experiments 2 and 3) per individual chicken in each test illumination. The illumination was switched immediately before the wall was removed (see the electronic supplementary material, video), allowing no adaptation time.

(f). Tests after long adaptation time

To test whether adaptation time in the shifted illumination improved colour constancy, we allowed chickens on two separate sessions to first make 10 training trials each before we shifted to an illumination in which they previously had failed to make correct colour discriminations. After giving both chickens 5 min to adapt to the test illumination, we allowed them to make four test trials.

(g). Comparison with previous experiments on goldfish and honeybees

We used Plot Digitizer [39] to extract the spectral sensitivities of the four cone types of the goldfish [40] and the illuminations, backgrounds and colour stimuli used in the behavioural experiment [15] (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). We examined the choice distributions to determine which colours were successfully discriminated from the training colour, employing the criterion of non-overlapping standard deviations between choices of the rewarded and the test colours. We concluded that colour constancy had failed when the peak of the choice distribution had shifted from the training colour. In the study on the honeybee [13], quantum catches of the three photoreceptor classes from all colour stimuli were estimated by measuring the intensity of three light sources matched to the spectral sensitivity of the three photoreceptor types (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). We concluded that the bees were not colour-constant when the choice distribution differed significantly between training and testing.

(h). Analysis

We analysed the data by fitting linear mixed-effects models, including individual identity as a random effect, via a logistic link function using the lme4 package [41] in R [42]. We compared the nested models using the change in deviance and by comparing the Aikake information criterion (AIC) [43]. To derive threshold illumination shifts, in which the chickens maintained colour constancy, we estimated a threshold halfway between the frequency of correct choice in the control illumination and random choice frequency (50%), along the fitted function. To evaluate whether choice frequencies were skewed towards the redder or yellower colour, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test in Matlab v. 2015a. To evaluate whether adaptation improved performance, we compared choice frequencies with and without adaptation with Friedman's test, also in Matlab. We additionally fitted logistic psychometric functions to the data (which can be found in the electronic supplementary material, figure S6). The estimated threshold from these differed very little from that of the GLMMs.

3. Results

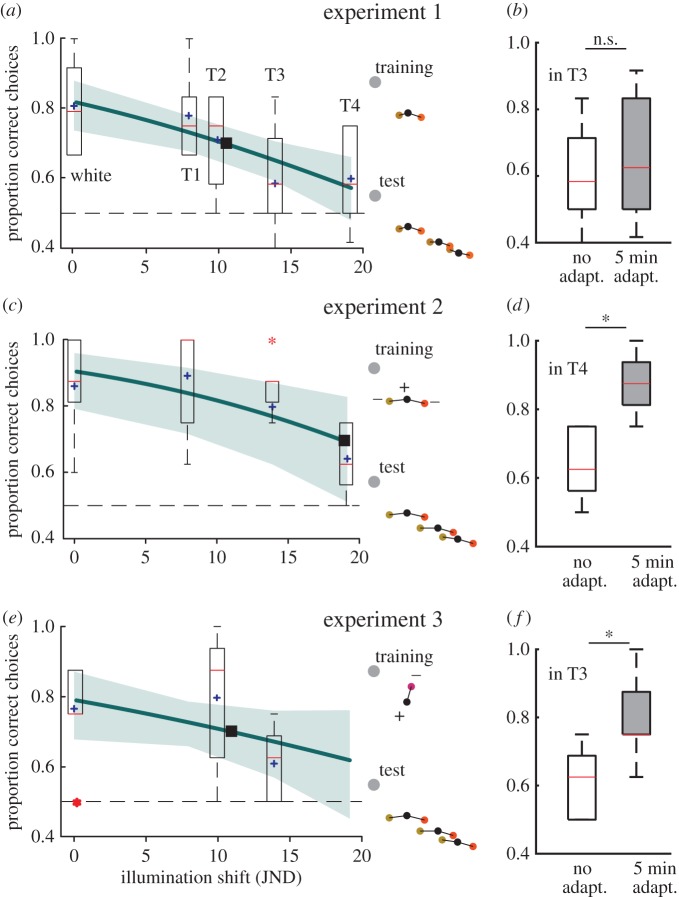

(a). Experiment 1, testing with small colour differences

Six chickens were trained to discriminate the rewarded colour (S+) from two unrewarded colours S1 and S2 that differed from S+ by 3 JNDs. In tests, the chickens discriminated the colours in the white control illumination and in red-shifted illuminations T1 (shift of 7.9 JNDs) and T2 (9.9 JNDs) but not in T3 (13.9 JNDs) and T4 (19.1 JNDs) (figure 3a). A mixed-effects logistic model, including the illumination shift as the fixed effect and the individual as a random variable was a better fit than a null model including only the effect of individual variation (AIC 437.51 versus 447.16; Δdeviance = −11.65, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001). The fitted function suggests that chickens discriminated the colours in illumination shifts smaller than 11 JNDs (figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Colour discrimination in the different illuminations (white, T1-4). (a,b) Experiment 1 (6 chickens × 12 choices). (c,d) Experiment 2 (8 chickens × 8 choices). (e,f) Experiment 3 (8 chickens × 8 choices). (a,c,e) Box plots of the correct choices plotted against illumination shifts. The red line refers to the median, the box contains 50%, the whiskers contain 99.3% of the data and the outliers are indicated by red asterisks. The fitted functions of the GLMMs (thick line), the standard error of the fit (shaded area), averages at each illumination shift (purple cross) and extrapolated threshold illumination shift (black box). Insets: colour loci of the colours used, indicating the training and testing conditions in the three experiments. Panels (b,d,f) show the performance with no adaptation time and after 5 min of adaptation time. Asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05 in a Friedman's test.

(b). Experiment 2, testing with large colour differences

Eight chickens learned to discriminate the rewarded colour (S+) from two unrewarded colours S3 and S4 that differed from S+ by 5 JNDs. They discriminated the colours in the control illumination and in T2 and T3, but not in T4 (figure 3c). A mixed-effects logistic model was a better fit than a null model (AIC 261.92 versus 253.48; Δdeviance = −10.44 d.f. = 1, p < 0.01). The chickens could discriminate the colours in illumination shifts smaller than 19 JNDs (figure 3c).

(c). Experiment 3, with different stimuli in training compared to testing

Eight chickens trained to discriminate the rewarded colour (S+) from an unrewarded colour (S5) were unable to discriminate S+ from two unfamiliar colours (S1 and S2) in the control illumination (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S7). They could discriminate S+ from S3 and S4 that have a larger colour difference from S+ in the control illumination and in T2, but not in T3 (figure 3e). A mixed-effects logistic model had a lower AIC score but no significant change in deviance (AIC 228.83 versus 229.24; Δdeviance = −2.41 d.f. = 1, p = 0.12). The chickens could discriminate the colours in illumination shifts smaller than 11 JNDs (figure 3e).

(d). Longer adaptation time

After 5 min of adaptation colour discrimination was improved, compared with immediate choices, in illuminations T4 in experiment 2 and T3 in experiment 3 (Friedman's test p < 0.05; figure 3d,f), but not T3 in experiment 1 (Friedman's test p > 0.05; figure 3b).

(e). Relative colour vision

Chickens did not choose the yellower colour more than the redder colour—nor the opposite—in any illumination in any experiment (Wilcoxon signed-rank test p > 0.05) except during the trials after long adaptation time in experiment 3 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test p < 0.05).

(f). Colour difference between natural illumination spectra

The colour difference experienced by the chicken visual system when moving between different natural illumination spectra (electronic supplementary material, figure S4), such as sunlight at different elevations and the light in deciduous forests, were between 1 and 11 JNDs, and thus consistently smaller than or similar to the threshold illumination shifts found for chicken colour constancy (table 2).

Table 2.

Colour difference (JNDs) between pairs of natural illuminations, see methods for reference.

| illumination 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| illumination 1 | sun 11.4° | sun 24° (cloudy) | sun −3° (cloudy) | rainforest (clearing) | coniferous forest |

| sun 24° (cloudy) | 1.1 | — | — | — | — |

| sun −3° (cloudy) | 0.8 | 0.3 | — | — | — |

| rainforest | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.9 | — | — |

| coniferous forest | 10.7 | 9.8 | 10 | 10.2 | — |

| deciduous forest | 5.6 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5 | 5.3 |

(g). Comparison with the goldfish and honeybee

In a previous experiment [15], goldfish were trained to a rewarded colour against several unrewarded blue and yellow colours, and tested in yellowish or bluish illuminations. According to our calculation, the goldfish behaved colour-constantly in illumination shifts corresponding of nine goldfish-specific JNDs for the bluish and 11 JNDs for the yellowish illumination shift (illuminations blue 3 and yellow 2 in [15]). They were not colour-constant in illumination shifts of around 17 JNDs (illumination blue 2 and yellow 1). In yellowish illuminations, the goldfish remained colour-constant discriminating colour differences of 5.6 JNDs (blue stimuli) or 4.5 JNDs (yellow stimuli), (b3 and y2 compared to t). In bluish illuminations they remained colour-constant with colour differences of 3.5 JNDs (blue stimuli) and 4.5 JNDs (yellow stimuli) (b2 and y2 compared to t). Goldfish thus remained colour-constant when the illumination changed roughly 2–2.5 times the colour difference between the stimuli. In another previous experiment [13], honeybees were trained to prefer a specific colour and tested in changed illuminations which created a spectral match of an unrewarded colour with the training colour in the original illumination. The illumination changed by the same amount as the stimuli. The honeybees remained colour-constant in illumination changes between 4.4 and 8.3 JNDs, but failed in some cases in illumination changes between 3.4 and 5.4 JNDs. The failures were most prominent when the illumination was long-wavelength-shifted [13].

4. Discussion

We have shown that chickens can discriminate a rewarded colour (S+) from unrewarded colours (S1–4) in spectrally different illuminations, confirming colour constancy in birds [18] (as cited by Neumeyer [21]). We found limits of colour constancy in the chicken as they failed to discriminate S+ with large changes of the illumination spectrum. It has been suggested that perfect colour constancy, the ability to completely compensate for all illumination changes, would in fact be maladaptive, as the spectrum of the illumination may itself contain valuable information [6]. Chickens remained colour-constant over illumination changes, which were three to four times larger than the colour difference between stimuli that they discriminated. This colour constancy performance seems sufficient to manage the shifts between natural illuminations, which are generally smaller than those used in our experiments (table 2), assuming that the natural stimuli have similar colour differences as those used here.

(a). The discrimination task and training method affect colour constancy performance

The chickens that were trained to discriminate stimuli with 5 JNDs (experiment 2) remained colour-constant in larger colour shifts of the illumination than the chickens tested with a smaller colour difference between the stimuli (3 JNDs; experiment 1). The ratio between the maximum illumination change, in which they remained colour-constant, and the colour difference between the stimuli used was similar in both experiments (3.4 and 3.8 for experiments 1 and 2, respectively).

In experiment 3, chickens did not remain colour-constant in as large colour shifts of the illumination as in experiment 2. Learning of the unrewarded colours in the discrimination task seems to facilitate correct choices in changed illuminations and thus colour constancy, a phenomenon that is also known in humans [44].

(b). Evidence for colour generalization

In experiment 3, the chickens did not discriminate S+ from S1 and S2 after learning to discriminate S+ from S5 (electronic supplementary material, figure S6). S1 and S2 had a much smaller colour difference from S+ than S3, S4 and S5. The threshold for colour generalization in chickens has recently—after the start of this project—been found to be 3 JNDs [45], equal to the colour differences between S+ and S1 and S2 (3 JNDs). Thus, our chickens may have generalized S+, S1 and S3.

(c). Long adaptation time improves colour constancy

In experiments 2 and 3, chickens made correct choices immediately in illuminations T1 and T2, but in illuminations T3 and T4 immediate choices were often incorrect. Colour constancy was improved after 5 min adaptation to illuminations T3 and T4, prior to stimulus presentation. This indicates that colour constancy is either based on a fast mechanism that compensates for relatively smaller amount of illumination shifts and a slower mechanism that is contributes at larger illumination shifts, or on one mechanism that acts over multiple time scales [46].

We did not critically evaluate the adaptation time required to maintain colour constancy in a specific illumination, which would be a valuable future study. Ecologically, it would allow an understanding of how quickly birds adapt to illumination changes that they encounter, for instance, when they enter the forest or nest, or forage in a patchy illumination.

(d). Framework for comparative studies of colour constancy in animals

Quantitative studies of colour constancy in humans often measure colour constancy indices. Testing a subject's ability to adjust the illumination for a test colour patch such that it matches a control colour patch in the control illumination [47,48]. An index of 1 means that the control and adjusted illuminations are identical. However, this index only informs us to what extent a given illumination change is compensated and does not necessarily inform us on the limits of the system, in terms of how large an illumination shift the animal can one remain colour-constant. Our aim was to find these limits by training the animals in a simple discrimination task and testing them in different illuminations until we found the maximum illumination shift they tolerated. We describe the shift of the illumination with the RNL model, and relate it to the colour difference between the colours that the animals were trained to discriminate.

With this framework in mind, we analysed colour constancy tests in the goldfish [15] and the honeybee [13]. Using rather robust assumptions on goldfish colour vision, we could show that goldfish remained colour-constant only in smaller illumination shifts than the chickens. In honeybees, the maximum illumination shifts tolerated were not critically evaluated. The largest illumination shift in which they remained colour-constant was smaller than for chickens, but the honeybee limits may have been underestimated. The bees failed in some illumination shifts, which was perhaps related to the part of the spectrum that was changed [13]. Using our new framework will allow quantitative comparison of colour constancy between different species, even with different visual systems.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christine Scholtyßek and Olle Lind for valuable feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript and for sharing ideas and natural illumination spectra. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback, and to James Foster for providing technical assistance in psychophysical analysis in R.

Ethics

All animal experiments were approved by an ethics committee (permit no. M6–12, Swedish Board of Agriculture).

Data accessibility

All data are available in the figures and tables and in the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

P.O. and A.K. designed the study. P.O. and D.W. performed all behavioural experiments. P.O., D.W. and A.K. analysed the data. P.O. wrote the manuscript with input from A.K. and D.W. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Human Frontiers Science Programme (RPG0017/2011), the Swedish Research Council (2012–2212), the Knut & Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2014-363).

References

- 1.Endler JA. 1993. The color of light in forests and its implications. Ecol. Monogr. 63, 1–27. ( 10.2307/2937121) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnsen S, Kelber A, Warrant EJ, Sweeney AM, Widder EA, Lee RL, Hernández-Andrés J. 2006. Crepuscular and nocturnal illumination and its effects on color perception by the nocturnal hawkmoth Deilephila elpenor. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 789–800. ( 10.1242/jeb.02053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurlbert AC. 2007. Colour constancy. Curr. Biol. 17, R906–R907. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanleeuwen MT, Joselevitch C, Fahrenfort I, Kamermans M. 2007. The contribution of the outer retina to color constancy: a general model for color constancy synthesized from primate and fish data. Visual Neurosci. 24, 277–290. ( 10.1017/S0952523807070058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbur JL, Spang K. 2008. Colour constancy and conscious perception of changes of illuminant. Neuropsychologia 46, 853–863. ( 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smithson HE. 2005. Sensory, computational and cognitive components of human colour constancy. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 360, 1329–1346. ( 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60023-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamermans M, Kraaij DA, Spekreijse H. 1998. The cone/horizontal cell network: a possible site for color constancy. Visual Neurosci. 15, 787–797. ( 10.1017/S0952523898154172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komatsu H. 1998. The physiological substrates of color constancy. In Perceptual constancy (eds Walsh V, Kulikowski J), pp. 352–372. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen T, Olkkonen M, Walter S, Gegenfurtner KR. 2006. Memory modulates color appearance. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1367–1368. ( 10.1038/nn1794) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chittka L, Faruq S, Skorupski P, Werner A. 2014. Colour constancy in insects. J. Comp. Physiol. A 200, 435–448. ( 10.1007/s00359-014-0897-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkenius A, Kelber A. 2004. Colour constancy in diurnal and nocturnal hawkmoths. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 3307–3316. ( 10.1242/jeb.01158) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumeyer C. 1981. Chromatic adaptation in the honeybee: successive color contrast and color constancy. J. Comp. Physiol. A 144, 543–553. ( 10.1007/BF01326839) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner A, Menzel R, Wehrhahn C. 1988. Color constancy in the honeybee. J. Neurosci. 8, 156–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingle DJ. 1985. The goldfish as a retinex animal. Science 227, 651–654. ( 10.1126/science.3969555) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dörr S, Neumeyer C. 2000. Color constancy in goldfish: the limits. J. Comp. Physiol. A 186, 885–896. ( 10.1007/s003590000141) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita M, Arikawa K. 2000. Colour constancy in the swallowtail butterfly Papilio xuthus. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 3521–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gniubkin VF, Kondrashev SL, Orlov OY. 1975. Contancy of color perception in the grey toad. Biofizika 20, 725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz D, Révész G. 1921. Experimentelle studien zur vergleichenden psychologie (versuch mit hühnern). Z. Angew. Psychol. 18, 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzhafarli MT, Maximov VV, Kezeli AR, Antelidze NB. 1991. Color constancy in monkeys. Sensornye Sistemy 5, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kezeli AR, Maximov VV, Homeriki MS, Anjaparidze S, Tschvediani NG. 1987. Colour constancy and lightness constancy in cats. Perception 20, 132. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumeyer C. 1998. Comparative aspects of colour constancy. In Perceptual constancy (eds Walsh V, Kulikowski J), pp. 323–351. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chavez J, Kelber A, Vorobyev M, Lind OE. 2014. Unexpectedly low UV-sensitivity in a bird, the budgerigar. Biol. Lett. 10, 20140670 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0670) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kries von J. 1905. Influence of adaptation on the effects produced by luminous stimuli. In Handbuch der phsyiology des menschen (ed. Nagel W.), pp. 190–282. Braunschweig, Germany: Vieweg. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renoult JP, Kelber A, Schaefer MH. In press Colour spaces in ecology and evolutionary biology. Biol. Rev. ( 10.1111/brv.12230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vorobyev M, Osorio DC. 1998. Receptor noise as a determinant of colour thresholds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 351–358. ( 10.1098/rspb.1998.0302) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brainard DH. 1998. Color constancy in the nearly natural image. 2. Achromatic loci. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 15, 307–325. ( 10.1364/JOSAA.15.000307) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smithson HE, Zaidi Q. 2004. Colour constancy in context: roles for local adaptation and levels of reference. J. Vis. 4, 3 ( 10.1167/4.9.3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Worthey JA, Brill MH. 1986. Heuristic analysis of von Kries color constancy. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 3, 1708–1712. ( 10.1364/JOSAA.3.001708) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart NS. 2001. The visual ecology of avian photoreceptors. Progr. Retinal Eye Res. 20, 675–703. ( 10.1016/S1350-9462(01)00009-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vorobyev M. 2003. Coloured oil droplets enhance colour discrimination. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 1255–1261. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vorobyev M, Osorio DC, Bennett ATD, Marshall JN, Cuthill IC. 1998. Tetrachromacy, oil droplets and bird plumage colours. J. Comp. Physiol. A 183, 621–633. ( 10.1007/s003590050286) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Backhaus WGK. 1998. Psysiological and psychophysical simulation of color vision in humans and animals. In Color vision: perspectives from different disciplines (eds Backhaus WGK, Kliegel R, Werner JS), pp. 45–77. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsson P, Lind OE, Kelber A. 2015. Bird colour vision: behavioural thresholds reveal receptor noise. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 184–193. ( 10.1242/jeb.111187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osorio DC, Vorobyev M, Jones CD. 1999. Colour vision of domestic chicks. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 2951–2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Håstad O, Victorsson J, Ödeen A. 2005. Differences in color vision make passerines less conspicuous in the eyes of their predators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6391–6394. ( 10.1073/pnas.0409228102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee DW. 1987. The spectral distribution of radiation in two neotropical rainforests. Biotropica 9, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osorio DC, Vorobyev M. 2005. Photoreceptor sectral sensitivities in terrestrial animals: adaptations for luminance and colour vision. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 1745–1752. ( 10.1098/rstl.1802.0004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones CD, Osorio DC. 2004. Discrimination of oriented visual textures by poultry chicks. Vis. Res. 44, 83–89. ( 10.1016/j.visres.2003.08.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huwaldt JA.2014. Plot digitizer. See http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/ .

- 40.Neumeyer C. 1992. Tetrachromatic color vision in goldfish: evidence from color mixture experiments. J. Comp. Physiol. A 171, 639–649. ( 10.1007/BF00194111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker BM, Walker S. 2014. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. See https://github.com/lme4/lme4.

- 42.R Core Team. 2014. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- 43.Aikake H. 1974. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 19, 716–723. ( 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Granzier JJM, Gegenfurtner KR. 2012. Effects of memory colour on colour constancy for unknown coloured objects. i-Perception 3, 190–215. ( 10.1068/i0461) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scholtyssek C, Osorio DC, Baddeley R. In press A simple Bayesian model describes color generalization across hue and saturation in chicks. J. Vis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Werner A. 2014. Spatial and temporal aspects of chromatic adaptation and their functional significance for colour constancy. Vis. Res. 104, 80–89. ( 10.1016/j.visres.2014.10.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arend LE, Reeves A, Schirillo J, Goldstein R. 1991. Simultaneous color constancy: papers with diverse Munsell values. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 8, 661–672. ( 10.1364/JOSAA.8.000661) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang JN, Shevell SK. 2002. Stereo disparity improves color constancy. Vis. Res. 42, 1979–1989. ( 10.1016/S0042-6989(02)00098-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the figures and tables and in the electronic supplementary material.