Abstract

Herein we report uncovering of a new function of personal glucose meter (PGM), namely, dose-dependent response of nicotinamide coenzymes (NADH), and developing a one-step homogeneous assay of targets that are difficult to be recognized by DNAzymes, aptamers or antibodies, and without the need for conjugation and multiple steps of sample dilution, separation, or fluid manipulation. The method is based on the target-induced consumption or production of NADH through cascade enzymatic reactions. Since a large number of commercially available enzymatic assay kits in the clinical labs utilize NADH in their detection, this discovery that links the readout function of PGM with NADH will allow transforming almost all of these clinical lab tests into POC tests using PGM.

Keywords: Glucose Meter, NADH, Blood Analysis, Point-of-Care Testing

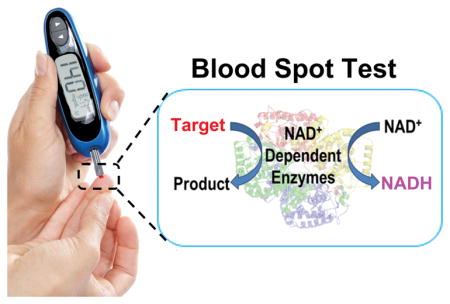

Graphical Abstract

A newly discovered function of glucose meter, namely, dose-dependent response of nicotinamide coenzymes (NADH), can serve as the signal readout for highly sensitive blood analysis in a single step.

Point-of-care (POC) devices that allow rapid, on-site, and affordable detection and monitoring of health biomarkers at home or away from clinical labs have received increasing attention in modern medicine.[1] Despite the importance, few POC devices are commercially available, partly due to high costs of research and development, and for those devices that are developed, they are often dedicated devices that can detect a single or limited targets. To overcome these limitations, we and others have taken advantage of existing POC devices, such as personal glucose meters (PGMs), and adapt them to measure a wide range of targets.[2] In doing so, we can bypass the costly development process and allow using a single device to measure many targets.[3] A key challenge in this endeavor is to find a way to translate recognition of many targets into an easily measurable signal using a PGM. To meet the challenge, we and others have demonstrated coupling of target binding by DNAzymes, aptamers, DNA and antibodies with enzymes such as invertase or glucoamylase, which can convert sugars that do not register any reading on PGM (e.g., sucrose and amylose) into glucose detectable by PGM.

Despite substantial progress made in the last few years with using the PGM to quantify non-glucose targets, there are still several issues that need to be addressed before its practical applications in clinical diagnostics is realized. First, the majority of these systems are limited to those targets that can be recognized by DNAzymes, aptamers, DNA or antibodies. Some progress has been made towards the use of PGMs for enzyme activity applications;[4] however, it either requires sophisticated syntheses of the enzyme substrates that covalently link to glucose or is not transferable to many targets as a general strategy. Second, they require conjugation of the recognition elements (e.g., apatamers or antibodies) with the enzymes through chemical/biochemical reactions that might affect the structure and activity of the enzyme.[2c, 2h, 2l] Third, many methods involve multiple sequential steps, including affinity capture on a solid surface (e.g. magnetic materials, electrode or microplate), physical separation, and chemical or biochemical signal amplifications,[2c, 2e–l, 2n] making it less user-friendly for POC applications. Finally, the interference of endogenous glucose to PGM readout in clinical samples is inevitable. A common strategy to circumvent this problem is to measure and subtract the background glucose signal from the signal obtained in the subsequent test.[2f–j] However, when the background signal is much larger than the signal generated by the target, especially for the detection of a trace amount of the target, the background subtraction method would be inaccurate. To address these issues, we herein report discovery of a new function of PGM, namely, dose-dependent response of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and taking advantage of this discovery to demonstrate a novel PGM-based detection of a wide range of targets using a single step and without the need for conjugation.

After decades of development, the majority of PGMs are based on an electrochemical reaction wherein the glucose is allowed to react with an enzyme electrode and the resulting change in the current/voltage is measured.[5] To facilitate the electron transfer to the electrode, most glucose test strips utilize redox mediators that couple the enzymatic reactions with electrochemical signals, thereby generating a current detected by a PGM (Figure S1). Since the signal transduction is related to the redox process of the mediator, we hypothesize that such a PGM system may also possess the ability to measure non-glucose species that could trigger the redox reaction of mediators located on the strips, without the need to transform the binding of non-glucose targets to glucose.[2c–l] In doing so, we will expand the utility of PGM to even wider range of targets.

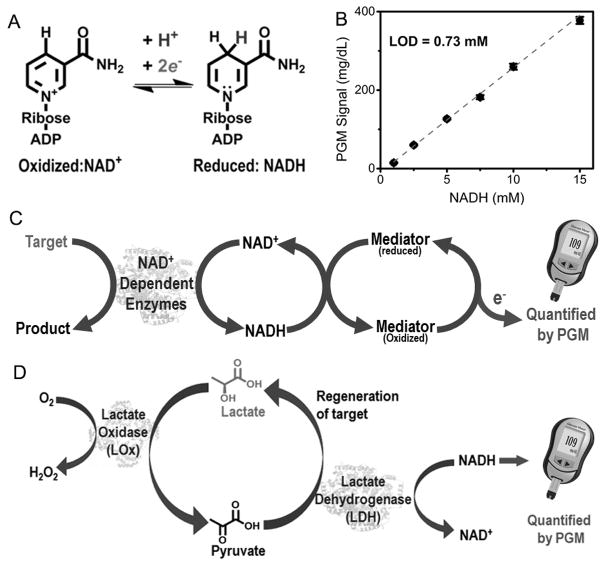

To test this hypothesis, we chose the nicotinamide coenzymes (e.g., NADH) as an ideal candidate, because the NADH/NAD+ redox pair (Figure 1A) is ubiquitous in all living systems and is required for the reactions of more than 450 oxidoreductases.[6] As shown in Figure 1B, the PGM shows a dose-dependent linear response to NADH in the range of 1.0–15.0 mM, while neither 100 mM NAD+ nor endogenous NADH in serum samples, reported to be in the range of 5–12 μM,[7] registered any reading on the PGM. The detection limit of NADH is 0.73 mM, which is compatible to that of glucose detection using the same glucose meter strips (Figure S2). To further verify the NADH triggered redox reaction on the glucose strips, we connected the strips with an electrochemical station (CH Instruments, Inc., USA), and monitored the cyclic voltammetric signals of the strips in the absence and presence of NADH, glucose, NAD+, and H2O2, respectively (Figure S3). Not surprisingly, both NADH and glucose showed enhanced signal response, while NAD+ produced negligible change. In addition, H2O2 produced a slightly decreased electrocatalytic signal, which resulted in no reading on the PGM. These results suggest that the mediator can oxidize NADH to NAD+, while the mediator itself is reduced; such a reduced mediator can then be re-oxidized at the electrode surface, producing an enhanced current signal that can be detected by the PGM (Figure 1C). Although other species (e.g., Fe2+) can react with the mediator and contribute to PGM readout, we found that these species could generate PGM signal only at a concentration above 1.0 mM (Figure S4), which is much higher than known concentrations of these species in clinical samples.

Figure 1.

(A) The electron transfer reactions between NAD+ and NADH. (B) The calibration for the NADH-dependent PGM signal. (C) Scheme of NADH-PGM system for target detection using NADH-dependent enzymes. (D) Schematic illustration of the L-lactate detection using NADH-PGM system

To evaluate the performance of this novel NADH-PGM system, we first investigated the use of this system for quantitative detection of L-lactate in plasma, which is measured routinely for clinical diagnosis and treatment of lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes,[8] monitoring tissue hypoxia and strenuous physical exertion,[9] and diagnosis of hyperlactatemia.[10] To achieve the goal, we employed lactate oxidase (LOx) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).[8, 11] As shown in Figure 1D, in the presence of sufficient amounts of NADH and oxygen, the L-lactate can be oxidized to pyruvate by LOx and the pyruvate formed can be subsequently reduced back to L-lactate by LDH. This enzymatic cascade reactions can keep the L-lactate concentration constant, so that the L-lactate serves not only as a detection target but also as an intermediate catalyst to amplify the signal. As a result, a trace amount of L-lactate can result in the consumption of high concentration of NADH within a short period of time, and thus increase the sensitivity by several orders of magnitude.

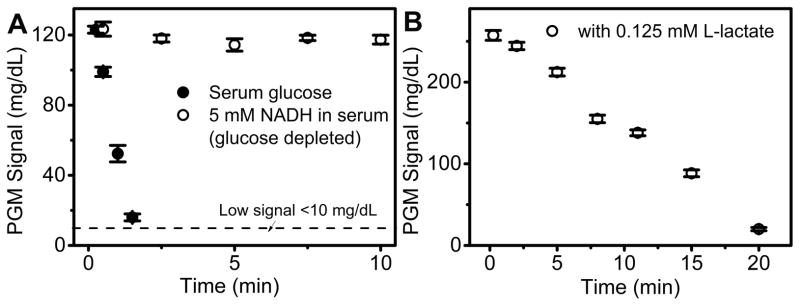

A major challenge of this NADH-PGM method is interference from endogenous glucose. To remove the interference, we employed another enzyme, hexokinase, which can catalyze the conversion of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate that is known to register no reading on the PGM. To test the feasibility of this method in L-lactate detection, 50 U/mL hexokinase was added into 200 mM HEPES buffer containing 20 mM glucose and 20 mM NADH, respectively. A rapid decrease of PGM signal for glucose was observed (Figure S5), while NADH readout signal showed negligible change. Encouraged by this result, we further apply this method for glucose removal in human serum. As shown in Figure 2A, the background glucose signal in serum decreased after the addition of hexokinase and reached a “LO” readout in 5 min. In contrast, the NADH in human serum, after glucose is depleted, gave a constant PGM readout. These results indicate that hexokinase can remove the background glucose signal efficiently and, more importantly, show no interference with the NADH signal.

Figure 2.

(A) The removal of endogenous glucose using hexokinase in human serum. NADH readout was monitored as control. The signal below the dash line represents < 10 mg/dL and shows as “LO” in the PGM. (B) Time-dependent NADH readout in PGM after the mixing of 8 μL Reagent A with 2 μL of Reagent B in 200 mM pH 7.5 HEPES buffer. Reagent A: 10 mM NADH, 8 U/mL LOX, 40 U/mL LDH, 50 mM ATP, 50 U/mL hexokinase. Reagent B: 0.125 mM L-lactate in HEPES buffer.

To demonstrate the multi-enzymatic cascade reaction shown in Figure 1D for L-lactate detection using NADH as PGM readout, 8 μL of Reagent A containing 10 mM NADH, 8 U/mL LOx, 40 U/mL LDH, 50 mM ATP, 50 U/mL hexokinase was added into 2 μL of Reagent B containing L-lactate, and a time-dependent NADH readout was monitored (Figure 2B). In the presence of 0.125 mM L-lactate, the NADH consumption rate was calculated to be −12.3 mg dL−1 min−1, which indicated a rapid PGM response toward L-lactate due to enzymatic lactate recycling reactions. The performance of NADH-PGM system for lactate detection was then investigated in HEPES buffer (Figure 3A). In a single step, 8 μL of reagent A was directly added into the lactate sample in HEPES buffer, and reacted at room temperature for 10 min. A quantitative relationship is established between the PGM signal and L-lactate concentration in HEPES buffer in the range of 0–2.0 mM, with a detection limit of 0.034 mM according to the definition of 3σb/slope (σb, standard deviation of the blank samples). Such a one-step homogeneous assay holds great promise for POC detection at home.

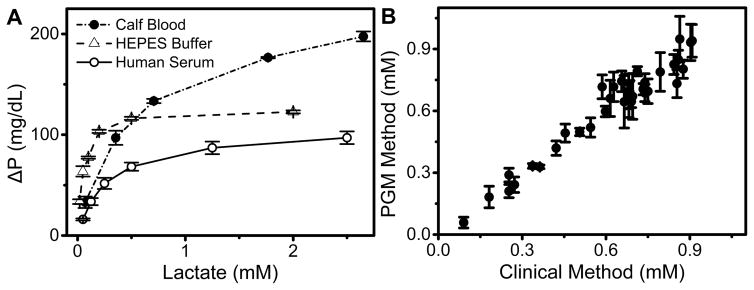

Figure 3.

(A) L-lactate detection in HEPES buffer, 100% human serum, and calf blood using the NADH-PGM system. ΔP is defined as PGM signal decrease after adding lactate to Reagent A. (B) Comparison of the NADH-PGM method with the standard clinical method using YSI Lactate Analyzer for L-lactate detection based on 36 samples in human plasma.

To demonstrate the compatibility of our method in complex biological samples, we further tested the L-lactate detection in 100% human serum and then calf blood (Figure 3A). First, a control experiment was performed to examine whether the calf blood will interfere with the added NADH. Not surprisingly, in the absence of LDH and LOx, the NADH consumption rate was calculated to be −0.1 mg dL−1 min−1 (Figure S6), much lower than that of 0.125 mM L-lactate in the presence of LDH and LOx (Figure 2B), indicating that the blood components showed negligible contribution to the NADH consumption in our method. Then, a series of human serum and calf blood samples were spiked with different concentrations of L-lactate. Under the same condition, the PGM signal showed similar trends with increasing concentrations of L-lactate in serum and blood (Figure 3A), exhibiting a detection limit of 0.14 mM and 0.11 mM, respectively. The lactate in calf blood samples showed a higher saturation PGM signal than in HEPES buffer and human serum samples, because the calf blood contained a larger amount of hemoglobin, whose binding of O2 may affect the kinetics of oxygen-sensitive multi-enzymatic cascade reaction shown in Figure 1D. In applications, a calibration using different samples is required to take into these different effects into consideration.

Since different users may have different concentrations of lactate in different samples, it is important to tune the dynamic range of the detection to match those in the user samples. The lactate detection in human serum was tuned from 0~2.5 mM to 0~25.0 mM by simply adjusting the ratio between NADH, LOx, and LDH (Figure S7). To verify the accuracy and reliability of our system against traditional spectroscopic method, the consumption of NADH in the presence of lactate, LDH and LOx in human serum was recorded at the 340 nm using a UV-Vis spectrometer (Figure S8). A good correlation between the two methods was observed (Figure S9). These results indicated that other components of the human serum or calf blood did not interfere significantly with the NADH signal.

Encouraged by the above successful L-lactate assays in biological samples, we further conducted similar tests in human plasma samples collected from diabetes during clinical treatment to demonstrate the utility of our method for clinical diagnosis. Figure 3B shows the comparison of the NADH-PGM method for L-lactate detection with the standard clinical method using YSI lactate Analyzer. A total of 36 samples in human plasma were evaluated. A strong positive correlation between these two methods was found, with a slope of 1.05 ™ 0.03 and a correlation coefficient of 0.97, demonstrating that the results from the two methods matched within the experimental errors. These results confirm that the accuracy of our NADH-PGM method is as good as that of the clinical L-lactate detection method, indicating the suitability and reliability of the NADH-PGM as an alternative test method for POC detection.

Furthermore, we took the advantage of the NADH-PGM system to demonstrate simultaneous monitor of the glucose and L-lactate levels in human plasma from patients with diabetes during clinical treatment, and a good correlation between NADH-PGM method and clinical method for both glucose and L-lactate monitoring was obtained (Figure S10). Given the facile integration of various NAD+-dependent enzymes into NADH-PGM system, the proposed method hold great promise to provide patients with a single-device solution that can monitor multiple biomarkers at home quantitatively.

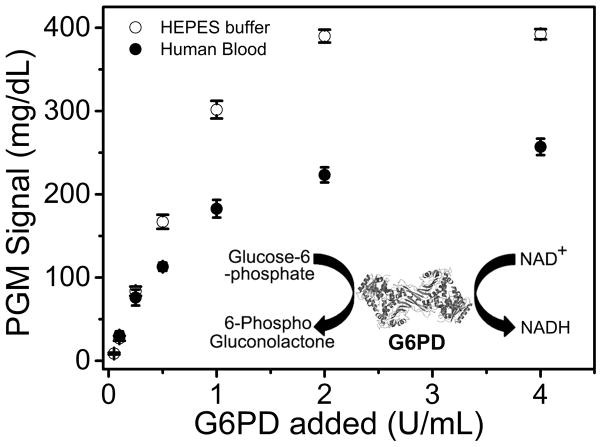

To demonstrate that our NADH-PGM method can be generally applied to other targets, we designed a sensor for Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD), which is the most common human enzyme defect, affecting approximately 400 million people worldwide.[12] Since G6PD can convert glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) to 6-phosphogluconolactone that couples reduction of NAD+ to NADH (Figure 4 inset), a single step mixing of G6PD with G6P and NAD+ resulted in production of NADH at a rate of 16.4 mg dL−1 min−1 (Figure S11). As a result, this NADH-PGM system allowed the quantitative analysis of G6PD activity in HEPES buffer and human blood (Figure 4), with a detection limit of 0.05 U/mL and 0.10 U/mL, respectively. These detection limits are lower than the normal G6PD level (0.49 to 2.8 U/mL, calculated from 0.135 g/mL hemoglobin),[13a] making it possible for potential application in G6PD deficiency diagnosis.

Figure 4.

(A) The enzymatic reaction of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) that convert NAD+ to PGM detectable NADH. (B) Measurement of G6PD activity in HEPES buffer and human blood.

In summary, we have designed a simple and general method based on the newly discovered capability of PGM to detect NADH, allowing rapid, portable, user-friendly, and cost-effective quantification of a wide range of non-glucose targets, including those that are difficult to be recognized by DNAzymes, aptamers and antibodies. Critical to the success of the method described in this work is the employment of a series of enzymatic reactions to link the target to the consumption of NADH in order to perform the test using a PGM. Our design allows simultaneous target detection and endogenous glucose removal homogeneously in one single step, by applying a small amount of reagent directly into clinical samples, avoiding any sample dilution, separation, or fluid manipulation steps. Although UV absorption and fluorescence of NADH have been used for the standard enzyme activity and metabolite assays when the NADH is formed or consumed in the presence of these targets, few portable devices taking advantage of these reactions suitable for POC applications are commercially available. Moreover, the optical signals of NADH in the standard assays are vulnerable to interference from colored species in the clinical samples (e.g., hemoglobin in blood). Procedures used in clinical labs to remove the colored species, such as centrifuging or ultra-filtering are not suitable for point-of-care applications. However, since multiple enzymes are employed in our system, each enzyme activity has to be carefully calibrated in order to ensure accurate results and reproducibility. Despite this issue, since NADH is a functionally important metabolite required to support numerous cellular processes and since a large number of commercially available enzymatic assay kits in the clinical labs utilize NADH in their detection,[13b] the newly discovered function of PGM can be easily expanded for the monitoring of a wide range of targets when coupled with various NADH-dependent enzymes. By converting the PGM into an all-purpose platform to monitor other biomarkers using NADH, this method open another new avenue to bypass the costly medical device development process, allowing millions of people to use the small, portable, and affordable PGMs they already own to monitor, literally at their finger-tips, not only their blood glucose, but also other relevant biomarkers regularly using a single monitoring device.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Mayo Clinic-University of Illinois Strategic Alliance for Technology-Based Healthcare and U.S. National Institutes of Health (ES16865) for financial supports.

References

- 1.a) Das J, Ivanov I, Montermini L, Rak J, Sargent EH, Kelley SO. Nat Chem. 2015;7:569–575. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) St John A. Clin Biochem Rev. 2010;31:111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Song Y, Huang YY, Liu X, Zhang X, Ferrari M, Qin L. Trends Biotechnol. 2014;32:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Tram K, Kanda P, Salena BJ, Huan S, Li Y. Angew Chem. 2014;53:12799–12802. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chapman R, Lin Y, Burnapp M, Bentham A, Hillier D, Zabron A, Khan S, Tyreman M, Stevens MM. ACS Nano. 2015;9:2565–2573. doi: 10.1021/nn5057595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Chen Y, Xianyu Y, Wang Y, Zhang X, Cha R, Sun J, Jiang X. ACS Nano. 2015;9:3184–3191. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zhu Z, Guan Z, Liu D, Jia S, Li J, Lei Z, Lin S, Ji T, Tian Z, Yang CJ. Angew Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1002/anie.201503963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Xiang Y, Lu Y. Anal Chem. 2012;84:1975–1980. doi: 10.1021/ac203014s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xiang Y, Lu Y. Anal Chem. 2012;84:4174–4178. doi: 10.1021/ac300517n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ma X, Chen Z, Zhou J, Weng W, Zheng O, Lin Z, Guo L, Qiu B, Chen G. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;55:412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mohapatra H, Phillips ST. Chem Commun. 2013;49:6134–6136. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43702g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Su J, Xu J, Chen Y, Xiang Y, Yuan R, Chai Y. Chem Commun. 2012;48:6909–6911. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32729e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wang Q, Wang H, Yang X, Wang K, Liu F, Zhao Q, Liu P, Liu R. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3824–3826. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00133h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Wang Q, Wang H, Yang X, Wang K, Liu R, Li Q, Ou J. Analyst. 2014 doi: 10.1039/c4an02033b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Xiang Y, Lu Y. Nat Chem. 2011;3:697–703. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Xu XT, Liang KY, Zeng JY. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;64:671–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Yan L, Zhu Z, Zou Y, Huang Y, Liu D, Jia S, Xu D, Wu M, Zhou Y, Zhou S, Yang CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3748–3751. doi: 10.1021/ja3114714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Yang W, Lu X, Wang Y, Sun S, Liu C, Li Z. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2015;210:508. [Google Scholar]; l) Zhu X, Xu H, Lin R, Yang G, Lin Z, Chen G. Chem Commun. 2014;50:7897–7899. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03553d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Du Y, Hughes RA, Bhadra S, Jiang YS, Ellington AD, Li B. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11039. doi: 10.1038/srep11039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Zhao Y, Du D, Lin Y. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;72:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Zhang X, Dhawane AN, Sweeney J, He Y, Vasireddi M, Iyer SS. Angew Chem. 2015;54:5929–5932. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p) Wang Z, Chen Z, Gao N, Ren J, Qu X. Small. 2015 doi: 10.1002/smll.201500944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Song Y, Zhang Y, Bernard PE, Reuben JM, Ueno NT, Arlinghaus RB, Zu Y, Qin L. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1283. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhu Z, Guan Z, Jia S, Lei Z, Lin S, Zhang H, Ma Y, Tian ZQ, Yang CJ. Angew Chem. 2014;53:12503–12507. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Mohapatra H, Phillips ST. Chem Commun. 2013;49:6134–6136. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43702g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang Q, Wang H, Yang X, Wang K, Liu R, Li Q, Ou J. Analyst. 2015;140:1161–1165. doi: 10.1039/c4an02033b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Wang J. Chem Rev. 2008;108:814–825. doi: 10.1021/cr068123a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Heller A, Feldman B. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2482–2505. doi: 10.1021/cr068069y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Clarke SE, Foster JR. Brit J Biomed Sci. 2012;69:83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Heller A. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:153–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yoo EH, Lee SY. Sensors. 2010;10:4558–4576. doi: 10.3390/s100504558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Mailloux S, Gerasimova YV, Guz N, Kolpashchikov DM, Katz E. Angew Chem. 2015;54:6562–6566. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Niazov T, Baron R, Katz E, Lioubashevski O, Willner I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17160–17163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608319103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zayats M, Kharitonov AB, Katz E, Buckmann AF, Willner I. Biosens Bioelectron. 2000;15:671–680. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(00)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Radoi A, Compagnone D. Bioelectrochemistry. 2009;76:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lin Y, Yu P, Hao J, Wang Y, Ohsaka T, Mao L. Anal Chem. 2014;86:3895–3901. doi: 10.1021/ac4042087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikirova N, Riordon HD, Rillema P. J Ortho Med. 2003;18:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rassaei L, Olthuis W, Tsujimura S, Sudholter EJ, van den Berg A. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406:123–137. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Pribil MM, Laptev GU, Karyakina EE, Karyakin AA. Anal Chem. 2014;86:5215–5219. doi: 10.1021/ac501547u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sardesai NP, Ganesana M, Karimi A, Leiter JC, Andreescu S. Anal Chem. 2015;87:2996–3003. doi: 10.1021/ac5047455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez EH, Dawood H, Chetty U, Esterhuizen TM, Bizaare M. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:553–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Romero MR, Ahumada F, Garay F, Baruzzi AM. Anal Chem. 2010;82:5568–5572. doi: 10.1021/ac1004426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rocchitta G, Secchi O, Alvau MD, Farina D, Bazzu G, Calia G, Migheli R, Desole MS, O’Neill RD, Serra PA. Anal Chem. 2013;85:10282–10288. doi: 10.1021/ac402071w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jia W, Bandodkar AJ, Valdes-Ramirez G, Windmiller JR, Yang Z, Ramirez J, Chan G, Wang J. Anal Chem. 2013;85:6553–6560. doi: 10.1021/ac401573r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nkhoma ET, Poole C, Vannappagari V, Hall SA, Beutler E. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2009;42:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S, Nguon C, Guillard B, Duong S, Chy S, Sum S, Nhem S, Bouchier C, Tichit M, Christophel E, Taylor WRJ, Baird JK, Menard D. Plos One. 2011;6:e28357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028357.; b) in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:NADH-dependent_enzymes.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.