Abstract

Background and study aims: Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is recommended following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent (DES). DAPT is a risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding. We aimed to quantify (1) the rate of gastroscopy within 12 months after PCI, (2) the rate of adverse cardiac events and gastroscopy-related bleeding complications within 30 days of gastroscopy, and (3) the association between antiplatelet therapy and these events.

Patients and methods: Patients receiving gastroscopy within 12 months of PCI were identified and two nested case-control analyses were performed within the PCI cohort by linking Danish medical registries. Cases were patients with adverse cardiac events (cardiac death, myocardial infarction, or stent thrombosis) or hemostatic intervention. In both studies, controls were patients with gastroscopy including biopsy without adverse cardiac events and hemostatic intervention, respectively. Medical records were reviewed to obtain information on exposure to DAPT.

Results: We identified 22 654 PCI patients of whom 1497 patients (6.6 %) underwent gastroscopy. Twenty-two patients (1.5 %) suffered an adverse cardiac event, 93 patients (6.2 %) received hemostatic intervention during or within 30 days of the index gastroscopy. Interrupting DAPT was associated with a 3.46 times higher risk of adverse cardiac events (95 %CI 0.49 – 24.7). Discontinuation of one antiplatelet agent did not increase the risk (OR 0.65, 95 %CI 0.17 – 2.47). No hemostatic interventions were caused by endoscopic complications.

Conclusion: Gastroscopy can be safely performed in PCI patients treated with DES and single antiplatelet therapy while interruption of DAPT may be associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiac events.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12-inhibitor (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or prasugrel) is recommended for up to 12 months following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with coronary drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation 1 2. Although DAPT reduces the risk of adverse cardiac events, it increases the risk of bleeding, particularly in relation to surgical procedures 3. As a consequence, the need for surgery or invasive procedures is a common reason for DAPT interruption 4. Surgery requiring interruption of DAPT may trigger adverse cardiac outcomes in patients with recent DES implantation 5.

The risk of adverse cardiac events and bleeding complications differs depending on the type of surgery 6. Gastroscopy is associated with an upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk < 1 % 7 and guidelines recommend continuing DAPT throughout gastroscopy with or without biopsy 7. However, adherence to guidelines is inconsistent and DAPT is sometimes interrupted for this minor invasive procedure 8, possibly because personal experience with bleeding complications may outweigh the perceived benefits of guideline recommendations 8.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has hitherto examined the association between DAPT strategy for PCI patients in relation to gastroscopy and the corresponding clinical outcomes. Subsequently, the aim of the present study was to quantify (1) the rate of gastroscopy within 12 months after PCI, (2) the rate of adverse cardiac events and gastroscopy-related bleeding within 30 days of gastroscopy, and (3) the association between antiplatelet therapy and these events.

Methods

The study was approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency (Ref: J.no. 2012-41-0164). The Danish Health and Medicines Authority approved medical record reviews (Ref: 3-3013-284/1). Registry studies do not require ethical approval in Denmark.

Study setting and participants

Patients receiving gastroscopy within 12 months of PCI were identified through Danish medical registries. We conducted two nested case-control analyses within this cohort by linking Danish medical registries. The nested case-control design allowed us to retrieve data from the patients’ medical records and to report accurate information with regard to the exact timing of DAPT in relation to gastroscopy with the same statistical precision but without having to review all medical records of PCI patients with subsequent gastroscopy.

The Danish Civil Registration System enabled us to collect information, linked at the individual level, from national and regional administrative and medical registries 9.

The Western Denmark Heart Registry (WDHR) collects patient and procedure information on all coronary interventions performed at the three coronary intervention centers in Western Denmark (Odense University Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, and Aalborg University Hospital). These centers cover a population of approximately three million inhabitants corresponding to 55 % of the Danish population 10. Our study population consisted of patients registered in the WDHR who were treated with one or more DES between July 2005 and December 2011 (n = 22 654). For each patient, the index PCI procedure was defined as the last PCI procedure performed during the study period. We excluded patients treated medically, with balloon angioplasty, or with bare metal stents only, since guidelines do not always stipulate 12 months of DAPT treatment for these indications. For each patient, the first gastroscopy after the index PCI was included.

The Danish National Patient Register (DNPR) contains data on all hospital contacts since 1995, including dates of hospitalization, outpatients and discharge diagnosis/procedures coded according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) 11. We linked WDHR and DNPR data to identify patients who underwent gastroscopy with or without biopsy (see Appendix) within 12 months after PCI.

Data were collected from three university hospitals and 18 community hospitals to ensure a broad description of DAPT strategies and complications.

Adverse cardiac events were defined as cardiac death, myocardial infarction, or definite stent thrombosis within 30 days following gastroscopy. Death was determined by using the Civil Registration System while information on cause of death (cardiac or non-cardiac) was retrieved from the Danish Registry of Causes of Death 12. Cardiac death was defined as an evident cardiac death or death from unknown causes. Myocardial infarction was identified in the DNPR and defined as an acute admission plus an ICD-10 discharge code of I21 11. Information on definite stent thrombosis was obtained from the WDHR and defined according to the Academic Research Consortium definition 13, and confirmed by review of medical records as described elsewhere 14 15 16.

For the nested case-control analysis addressing adverse cardiac events following gastroscopy, cases were patients experiencing adverse cardiac events within 30 days following gastroscopy. For each case, we identified four control patients who had a gastroscopy within 12 months after PCI, but experienced no adverse cardiac events. The controls were matched by age (± 5 years), gender, and anticoagulant therapy with warfarin or phenprocoumon. Information on use of these drugs was retrieved from the DNPR, which has collected individual-level data on all prescription drugs sold in Danish pharmacies since 1994. The drugs are recorded with Anatomic Therapeutic Codes (ATC) 17.

Gastroscopy-related bleeding complications were defined as hemostatic interventions (adrenalin injection or electrocoagulation; ICD-10 codes are stated in the Appendix). Hemostatic interventions served as a surrogate marker for gastroscopy-related bleeding complications, since the DNPR contains specific codes for hemostatic intervention and since gastroscopy-related bleeding complications in most instances will lead to hemostatic intervention.

For the nested case-control study addressing gastroscopy-related bleeding events, cases were patients receiving hemostatic intervention during or within 30 days following the index gastroscopy. For each case, we identified two controls with gastroscopy with biopsy, but without hemostatic intervention, to ensure a comparative risk of bleeding. The controls were matched by age (± 10 years), gender, and anticoagulant therapy (using ATC codes for warfarin and phenprocoumon). Compared to the first case-control study, matching criteria (age) and number of controls were altered to allow for sufficient matching.

One investigator (GE) systematically reviewed the medical records of the selected cases and controls in the two nested case-control studies. We recorded treatment status (on or off treatment) for aspirin and P2Y12-inhibitors during the period 30 days before and 30 days after gastroscopy.

In the nested case-control analyses, patients were categorized as receiving periprocedural antiplatelet treatment when treatment was administered within 3 days before the gastroscopy. DAPT was defined as treatment with both aspirin and a P2Y12-inhibitor. Single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) was defined as treatment with only one antiplatelet agent (aspirin or P2Y12-inhibitor), and interrupting DAPT was defined as no antiplatelet treatment within 3 days before gastroscopy. Periprocedural treatment was registered for aspirin and P2Y12-inhibitors separately. Gastroscopies were defined as acute when performed within 3 days of acute admission.

Baseline data and covariates

For each patient, we computed comorbidity scores using the Charlson Comorbidity Index. This index covers 19 major disease categories, including diabetes mellitus, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, and cancer. This score is a weighted summary of previous diagnoses, with weights based on the 1-year mortality associated with each disease in the original Charlson dataset. The Charlson Comorbidity Index has recently been validated in a cohort of acute coronary syndrome patients 18. In this study, we used an adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index score that did not include diabetes and previous myocardial infarction since these two conditions were considered separately.

Data on prescription medication not obtained from medical records were obtained from the DNPR (see Appendix for ATC codes) 17. Patients were considered to be on treatment when a prescription was redeemed within 100 days before gastroscopy. Further demographic and clinical data were collected from the WDHR.

Since the risk of adverse cardiac events associated with DAPT discontinuation declines with time after PCI 19, we also calculated time from index PCI to gastroscopy. We defined and categorized gastroscopy as acute when performed within 3 days after acute admission.

Statistics

Baseline variables were presented as counts (%) apart from age, which was stated as median (interquartile range; IQR (Q1 – Q3)). In the nested case-control studies, we used conditional logistic regression to compute odds ratios for adverse cardiac events and gastroscopy-related bleeding complications among the different periprocedural antiplatelet strategies. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, United States).

Results

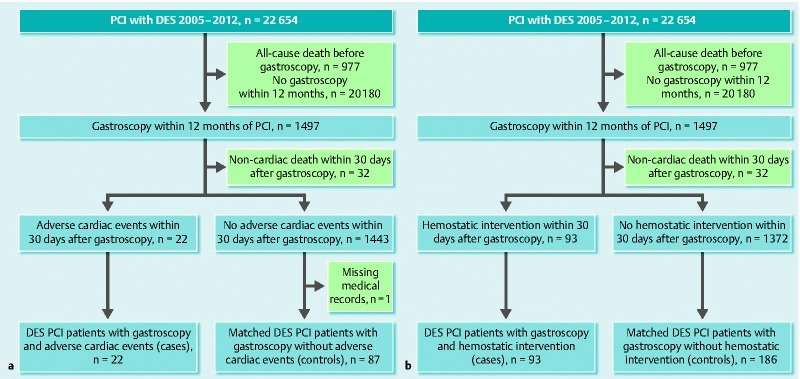

In a cohort of 22 654 patients treated with coronary DES implantation, we identified 1497 patients (6.6 %) who underwent gastroscopy within 12 months of PCI; of these, 1046 had gastroscopy with biopsy. Within 30 days after gastroscopy, 45 (3 %) patients died. Thirteen of these suffered a cardiac death while nine had a myocardial infarction, two of which were caused by stent thrombosis, yielding a total of 22 (1.5 %) adverse cardiac events within the first 30 days following gastroscopy. Ninety-three patients (6.2 %) received hemostatic intervention during gastroscopy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection for the nested case-control studies. a Adverse cardiac events nested case-control study. b Hemostatic interventions during gastroscopy nested case-control study. DES, drug-eluting stent; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

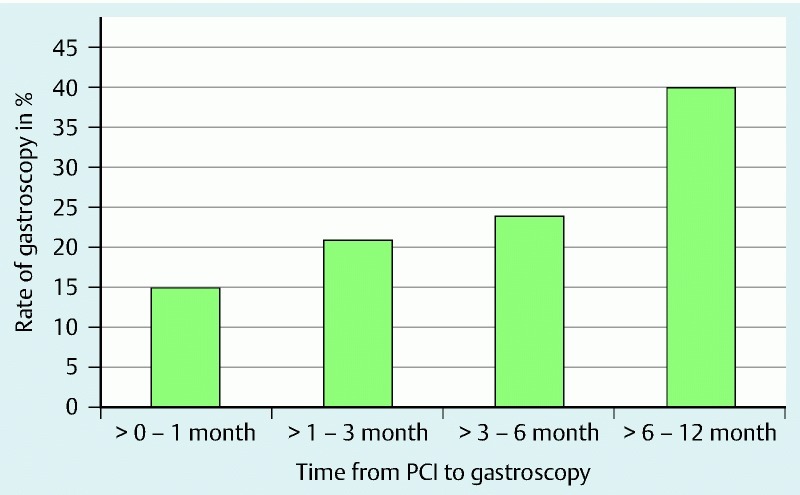

For the nested case-control studies, we collected information from the medical records of 109 patients in the adverse cardiac events study and 279 patients in the hemostatic intervention study. A single medical record (a control from the adverse cardiac events nested case-control study) was not obtainable and was recorded as missing. The gastroscopies were performed with a median time after PCI of 145 days (IQR, 60 – 249) (Fig. 2). P2Y12-inhibitors were clopidogrel for cases and controls, apart from four controls in the gastroscopy related bleeding group on ticagrelor.

Fig. 2.

Time from DES implantation to gastroscopy. The incidence (percentage) of gastroscopy in PCI patients, categorized by time from PCI to gastroscopy.

Adverse cardiac events

In the nested case-control study focusing on adverse cardiac events, data were obtained for 22 cases and 87 gastroscopy controls. The median time from PCI to gastroscopy was 132 days (IQR, 33 – 248 days) for cases and 125 days (IQR, 48 – 224 days) for controls. Demographic and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data for patients in the two nested case-control studies.

| Adverse cardiac event study | Gastroscopy-related bleeding event study | |||

| Cases, n = 22 | Controls, n = 87 | Cases, n = 93 | Controls, n = 186 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), years | 73 (66 – 79) | 73 (66 – 79) | 72 (65 – 79) | 71 (64 – 79) |

| Sex, male, no. (%) | 12 (54.5) | 48 (54.5) | 71 (76.0) | 142(76.0) |

| Smoking, no. (%) | 5 (23.8) | 16 (18.3) | 25 (26.8) | 43 (23.1) |

| Drug exposure, no (%) | ||||

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 9 (40.9) | 38 (45.8) | 32 (36.0) | 96 (52.75) |

| Statins | 10 (45.5) | 57 (68.7) | 69 (77.5) | 138 (75.8) |

| Vitamin K-antagonists | 3 (13.6) | 14 (16.9) | 8 (9.0) | 17 (9.3) |

| NSAIDs | 1 (4.5) | 9 (10.9) | 12 (13.5) | 6 (3.3) |

| Cox 2-inhibitors | 3 (13.6) | 4 (4.8) | 11 (12.4) | 12 (6.6) |

| Oral glucocorticoids | 2 (9.0) | 12 (14.5) | 11 (12.4) | 15 (8.2) |

| Calcium antagonists | 6 (27.3) | 34 (41.0) | 21 (23.6) | 52 (28.6) |

| Beta blockers | 12 (54.5) | 51 (61.5) | 60 (67.4) | 136 (74.7) |

| SSRIs | 2 (9.0) | 11 (13.2) | 12 (13.5) | 30 (16.5) |

| Nitrates | 4 (18.2) | 14 (16.9) | 18 (20.2) | 33 (18.1) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 11 (61.1) | 49 (63.6) | 47 (58.8) | 105 (66.5) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, no. (%) | 7 (38.9) | 46 (60.5) | 46 (57.5) | 105 (66.5) |

| Previous MI, no. (%) | 3 (16.7) | 21 (26.9) | 20 (25.6) | 33 (20.9) |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 2 (9.0) | 15 (17.2) | 15 (16.3) | 28 (15.2) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index,1 mean | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Lesion and procedural characteristics | ||||

| Stent > 1, % | 55 | 36 | 33 | 32 |

| Stent length > 20 mm, % | 62.1 | 45.2 | 48.6 | 49.3 |

| PCI indication ACS, no. (%) | 13 (59) | 40 (45) | 59 (63) | 94 (51) |

| PCI indication SAP, no. (%) | 8 (36) | 44 (50) | 31 (33) | 87 (47) |

| Indication2 UGIH, no. (%) | 17 (77) | 31 (35) | 93 (100) | 48 (26) |

| Indication2 dyspepsia, no. (%) | 5 (23) | 31 (35) | 0 | 25 (13) |

| Indication2 anemia, no. (%) | 0 | 24 (27) | 0 | 111 (60) |

IQR, interquartile range; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Cox, cyclooxygenase; SSRIs, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; SAP, stable angina pectoris; UGIH, upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Modified score, see Methods section.

Indication for gastroscopy.

In this nested case-control cohort including 109 patients, 91 % received aspirin and 97 % received a P2Y12-inhibitor before gastroscopy. Treatment with these drugs was interrupted > 3 days before gastroscopy for 24 % of the patients taking aspirin and for 23 % of patients taking P2Y12-inhibitors. Aspirin or a P2Y12-inhibitor treatment was resumed in 9 % and 14 % of patients, respectively, within 7 days following gastroscopy.

Among patients with an adverse cardiac event, 9 % did not receive any antithrombotic treatment at the time of gastroscopy and 77 % received DAPT (Table 2). The risk of cardiac events was 3.46 times higher among patients not receiving antiplatelet therapy compared to those receiving DAPT (95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.49 – 24.71). Single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) was not associated with an increased risk compared to DAPT therapy (odds ratio (OR) 0.65, 95 %CI 0.17 – 2.47).

Table 2. Periprocedural antiplatelet treatment in patients included in the nested case-control studies.

| Group | DAPT | Only a P2Y12-inhibitor | Only aspirin | No treatment |

| Adverse cardiac event study | ||||

| Cases (N = 22), no. (%) | 17 (77) | 1 (5) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) |

| Controls (N = 87), no. (%) | 67 (77) | 12 (14) | 6 (7) | 2 (2) |

| Gastroscopy-related bleeding event study | ||||

| Cases (N = 93), no. (%) | 79 (85) | 5 (5.5) | 5 (5.5) | 4 (4) |

| Controls (N = 186), no. (%) | 138 (74) | 18 (10) | 19 (10) | 11 (6) |

DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy.

Gastroscopy-related bleeding

In the nested case-control study of gastroscopy-related bleeding, we obtained data from 93 cases receiving a hemostatic intervention and 186 controls without such intervention. The median time from PCI to gastroscopy was 114 days (IQR, 52 – 224 days) for cases and 166 days (IQR, 70 – 267 days) for controls. Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table1 and periprocedural treatment in Table 2.

In this nested case-control cohort of 279 patients, 92 % received aspirin and 94 % a P2Y12-inhibitor before gastroscopy. Treatment with these drugs was interrupted > 3 days before gastroscopy for 37 % of the patients taking aspirin and for 33 % of the patients taking P2Y12-inhibitors. Aspirin or P2Y12-inhibitor treatment was resumed in 15 % and 20 % of patients, respectively, within 7 days following gastroscopy.

A total of 1046 patients had gastroscopy with biopsy. Using hemostatic intervention as a surrogate marker for bleeding complications, none of these 1046 patients had complications in relation to the biopsies.

All 93 cases who received a hemostatic intervention had suffered spontaneous bleeding before gastroscopy. Of these, 91 hemostatic interventions were performed during index gastroscopy and two at a new gastroscopy within 30 days. Thus, none of the hemostatic interventions were caused by gastroscopy-related bleeding complications due to biopsy. Gastroscopy was performed acutely in 84 cases (90 %) while the remaining cases had gastroscopy performed electively. In the control group, 129 gastroscopies (69 %) were performed electively.

None of the controls had a hemostatic intervention within 30 days after gastroscopy. Among cases, 85 % received DAPT, 11 % received single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) and 4 % received no periprocedural antiplatelet treatment. After initial gastroscopy, 13 cases and two controls had re-gastroscopy on suspicion of active bleeding during admission; however, no active bleeding was found.

Discussion

In this population-based cohort, gastroscopy was required in 6.6 % of patients within the first year after PCI with DES. Of these, 1.5 % suffered an adverse cardiac event and 6.2 % had a hemostatic intervention within 30 days following gastroscopy. Interrupting DAPT seemed to be associated with an increased risk of cardiac events in our cohort. Importantly, continuation of a single antiplatelet agent in relation to gastroscopy had the same protective effect against adverse cardiac events as DAPT. Review of the medical journals revealed that none of the cases in need of a hemostatic intervention had the intervention due to complications related to gastroscopy regardless of their antiplatelet therapy, and none of the controls required hemostatic intervention after biopsy, therefore SAPT or DAPT should thus not be a contraindication for hemostatic intervention or biopsy during gastroscopy.

Adverse cardiac events related to gastroscopy

The adverse cardiac event rate of 1.5 % within 30 days following gastroscopy in our study population should be considered in the light of a reported event rate of 5 % within 9 months among patients treated with DES 16. There are limited reports with regard to adverse cardiac events following gastroscopy 20 21 22 23 and we can only extrapolate from settings not involving procedures following PCI. We speculate that the explanation for the higher rate of adverse cardiac events observed here, apart from pre-existing cardiovascular disease, may be hemodynamic instability or a pro-thrombotic state related to bleeding events due to hypovolemia. In our cohort, 43 % of gastroscopies were performed due to clinically manifest, or suspicion of, upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Also, the indication for gastroscopy, i. e. confirmed or suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding, may be associated with interruption of antiplatelet treatment. We found a high compliance rate of 77 % for DAPT during gastroscopy for both cases and controls, resulting in very little information contrast rendering the confidence interval broad and the odds ratio without a traditional statistical significance of 5 %. However, a relative risk of 3.46 for an adverse cardiac event if the patients do not receive any DAPT during gastroscopy is not negligible.

The Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommends continuation of DAPT throughout gastroscopy in these patients 7. A recently reported survey among endoscopists noted that only 30 % of responding endoscopists adhered to the ASGE guidelines on antiplatelet therapy in relation to endoscopic procedures. Among respondents, 26 % withheld all antiplatelet therapy before engaging in any patient procedure, possible exposing the patients to an increased ischemic risk 8. DAPT interruption in patients with DES is a strong predictor of ischemic events 5 24. However, while discontinuation of both aspirin and clopidogrel, one of the available P2Y12-inhibitors, was associated with stent thrombosis, continuation of aspirin and discontinuation of clopidogrel was not 24 25. Accordingly, we found that reduction in periprocedural DAPT to a single antiplatelet agent, but with no difference between aspirin and clopidogrel, yielded the same protection against cardiac events as DAPT. Consequently, reduction in DAPT to aspirin or clopidogrel alone seems a safe choice in patients on DAPT who await gastroscopy on the suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Risk of gastroscopy-related bleeding in patients with DES implantation

Most importantly, we found that neither cases nor controls in the two nested case-control studies had bleeding episodes as a complication to gastroscopy with or without biopsy despite the high rate of periprocedural DAPT. These data strongly suggest that both elective and acute gastroscopy can be performed safely in patients receiving DAPT, although short intermittent reduction to a single antiplatelet agent also seems safe with regard to adverse cardiac events. Aspirin is known to injure the gastric mucosa while clopidogrel does not 26. In the randomized, blinded CAPRIE study of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischemic events, gastrointestinal bleeding was significantly less frequent in patients treated with clopidogrel 75 mg daily vs. aspirin 325 mg daily (0.52 % vs. 0.72 %) 27 while a prospective, randomized study involving 630 biopsies in healthy volunteers found no clinically important bleeding regardless of treatment with aspirin or clopidogrel 28. The added effect of clopidogrel and aspirin further increases the relative risk of bleeding up to 50 %. These studies thus indicate that aspirin and clopidogrel have very similar risks of gastrointestinal bleeding when used separately while the combined use increases the risk of bleeding. In this setting, it is important to note that our data support the recommendations that DAPT should not be routinely interrupted before gastroscopy and also that hemostatic intervention or biopsy can be performed safely in patients receiving aspirin and/or a P2Y12-inhibitor within 3 days before gastroscopy.

Collective strategy for patients undergoing gastroscopy after PCI

The optimal treatment strategy for a patient with gastrointestinal bleeding, who has recently undergone a PCI procedure, is complex with competing risks of rebleeding and adverse cardiac events. The recently updated European Joint Task Force Guidelines on Non-cardiac Surgery 6 recommends continued DAPT at the time of gastroscopy, but acknowledges the absence of randomized clinical trial data supporting this and that clinical circumstances with bleeding complications may necessitate suspension of either one or both antiplatelet agents 6.

In our study, we included both acute and elective gastroscopies to cover the diversity among patients needing a gastroscopy. This also means that, in some patients, there was no time to reduce DAPT. Despite this, no complications were observed which were directly related to hemostatic intervention or biopsy, which falls in line with the guidelines. Nevertheless, the challenge is patients who are under suspicion for upper gastrointestinal bleeding while on DAPT, leading to gastroscopy.

In our study, the majority of cases had acute gastroscopy and hence there was no opportunity to plan a treatment strategy. Even so, no cases had further bleeding leading to hemostatic intervention after the initial gastroscopy. From the potential decreased bleeding risk by reduction from DAPT to a single antiplatelet agent, and based on our finding of a low risk of adverse cardiac events in patients treated with a single antiplatelet agent, we advocate a single antiplatelet strategy for a shorter period in patients with a suspected acute bleeding episode. The clinical situation, the comorbidities, and the risk stratification by gastroscopy, will allow the treating physician to judge if, and when, DAPT can be re-initiated. Among elective patients, our data indicate that it is safe to either continue DAPT or reduce DAPT to a single antiplatelet agent 3 days before gastroscopy. The combined evidence from several studies including the current study indicate that it is safe to reduce DAPT to SAPT, whereas stopping both antiplatelet agents is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiac events 29 30 31. In Denmark, the guidelines only stipulate proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment for patients on DAPT, if the patients have risk factors for ulcer present at the time of PCI. The proportions of patients on PPI treatment were relatively low. Since 6.6 % of DES-treated patients undergo gastroscopy within 12 months and since PPIs reduce the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding 32, one may consider making PPI treatment the standard of care in patients receiving DAPT.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of our study is its combined evaluation of both 30-day risk of adverse cardiac events and 30-day bleeding risk following gastroscopy. We were able to identify the patients who suffered adverse cardiac events using Danish registries with documented validity 10. In addition, individual patient medical records were thoroughly examined to extract specific information about procedures, outcomes, and medical therapy. Nevertheless, separating adverse cardiac events from bleeding events is not straightforward since an important interaction between the two types of events is likely as major bleeding may lead to myocardial infarction. Major bleeding, compared to minor bleeding, is associated with a higher risk of interrupting both aspirin and P2Y12-inhibitor treatment and of pro-thrombotic states, blood transfusions, and hemodynamic instability, all of which may affect the risk of adverse cardiac events. Our risk estimates were imprecise with broad confidence intervals since compliance to DAPT was relatively high and event rates relatively low despite evaluating all 1497 gastroscopies in a cohort of 22 654 PCI patients. Our study was restricted to patients treated with DES, which represents more than 90 % of all patients in the WDHR during the study period. DAPT is usually discontinued 3 – 5 days before a surgical procedure. During this interruption, patients may suffer an adverse cardiac event before the gastroscopy with consequent cancellation of the procedure. Such incidents could not be detected with our study design. Evaluating the patient’s record gave us information on indication for gastroscopy. In the reoperation for bleeding study, the indication for cases was more often upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage compared to controls; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that this is due to information bias as a patient in need of a hemostatic intervention could more likely be classified as having upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage as indication whereas the indication anemia might be used if there is no active bleeding.

Conclusions

Gastroscopy is common within the first year after stent implantation, and management of the PCI-related DAPT represents a clinical challenge. We observed a relatively high risk of adverse cardiac events and hemostatic interventions. A single antiplatelet strategy may reduce the need for hemostatic intervention while, in accordance with previous studies, interruption of both antiplatelet agents seems associated with adverse cardiac events. A single antiplatelet strategy does thus seem recommendable in patients suspected of having upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Appendix

Table 3. ICD 10 codes used.

| ICD 10 code | |

| Gastroscopy with or without biopsy | KUJD02, KUJD05 |

| Hemostatic interventions (adrenalin injection or electrocoagulation) | KJDA32, KJDA 35, KJDH18, and KJDH15 |

Table 4. ATC codes for redeemed prescription medications within 100 days before surgery.

| Medication | ATC code |

| Vitamin K antagonists | B01AA03, B01AA04 |

| Statins | C10AA01-2, C10AA04-5 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | A02BC01, A02BC02, A02BC03, A02BC04, A02BC05 |

| Calcium channel blockers | C08CA01-3, C08CA05, C08CA08, C08CA09, C08CA13, C08CX01, C08DA, C08DB01 |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors | M01AH, M01AB05, M01AB55, M01AB08, M01AC06, M01AX01 |

| Nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | M01AB01, M01AC01, M01AE01, M01AE51, M01AE02, M01AE03, M01AE53, M01AE14, M01AG02 |

| Systemic glucocorticoids | H02AB |

| Beta blockers | C07 |

| Anti-depressives (SSRIs) | N06AB04, N06AB10, N06AB03, N06AB05, N06AB06 |

| Nitrates | C01DA02 |

| Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) | B01AB05, B01AB10, B01AB04 |

SSRIs, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.King S B 3rd, Smith S C Jr, Hirshfeld J W Jr. et al. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:172–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silber S, Albertsson P, Aviles F F. et al. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions. The Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:804–847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger P B, Bhatt D L, Fuster V. et al. Bleeding complications with dual antiplatelet therapy among patients with stable vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease: results from the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) trial. Circulation. 2010;121:2575–2583. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.895342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossini R, Capodanno D, Lettieri C. et al. Prevalence, predictors, and long-term prognosis of premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy after drug eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capodanno D, Angiolillo D J. Management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease requiring cardiac and noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 2013;128:2785–2798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristensen S D, Knuuti J, Saraste A. et al. 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2383–2431. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee . Anderson M A, Ben-Menachem T. et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanakadandi V, Parasa S, Sihn P. et al. Patterns of antiplatelet agent use in the US. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E173–178. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen C B. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt M, Maeng M, Jakobsen C J. et al. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: The Western Denmark Heart Registry. Clin Epidemiol. 2010;2:137–144. doi: 10.2147/clep.s10190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynge E, Sandegaard J L, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:26–29. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutlip D E, Windecker S, Mehran R. et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christiansen E H, Jensen L O, Thayssen P. et al. Biolimus-eluting biodegradable polymer-coated stent versus durable polymer-coated sirolimus-eluting stent in unselected patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention (SORT OUT V): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:661–669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61962-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeng M, Tilsted H H, Jensen L O. et al. Differential clinical outcomes after 1 year versus 5 years in a randomised comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting coronary stents (the SORT OUT III study): a multicentre, open-label, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2014;383:2047–2056. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen L O, Thayssen P, Hansen H S. et al. Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting stents in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: the Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials with Clinical Outcome IV (SORT OUT IV) Circulation. 2012;125:1246–1255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kildemoes H W, Sorensen H T, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:38–41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radovanovic D, Seifert B, Urban P. et al. Validity of Charlson Comorbidity Index in patients hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome. Insights from the nationwide AMIS Plus registry 2002–2012. Heart. 2014;100:288–294. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thim T, Johansen M B, Chisholm G E. et al. Clopidogrel discontinuation within the first year after coronary drug-eluting stent implantation: an observational study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossmann R, Borsch G, Ricken D. Cardiovascular complications of gastroenterologic endoscopy. Leber Magen Darm. 1987;17:371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang M C, Lee A Y, Chen T J. et al. Acute myocardial infarction after upper gastrointestinal gastroscopy. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 2001;64:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee C T, Huang S P, Cheng T Y. et al. Factors associated with myocardial infarction after emergency endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in high-risk patients: a prospective observational study. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strobl S, Zuber-Jerger I. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding after coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Med Klin (Munich) 2010;105:296–299. doi: 10.1007/s00063-010-1044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehran R, Baber U, Steg P G. et al. Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PARIS): 2 year results from a prospective observational study. Lancet. 2013;382:1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura T, Morimoto T, Nakagawa Y. et al. Antiplatelet therapy and stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2009;119:987–995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fork F T, Lafolie P, Toth E. et al. Gastroduodenal tolerance of 75 mg clopidogrel versus 325 mg aspirin in healthy volunteers. A gastroscopic study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:464–469. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CAPRIE Steering Committee . A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitson M J, Dikman A E, von Althann C. et al. Is gastroduodenal biopsy safe in patients receiving aspirin and clopidogrel? a prospective, randomized study involving 630 biopsies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:228–233. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181eb5efd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tokushige A, Shiomi H, Morimoto T. et al. Incidence and outcome of surgical procedures after coronary bare-metal and drug-eluting stent implantation: a report from the CREDO-Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort-2. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:237–246. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.963728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdel Samie A, Theilmann L. Endoscopic procedures in patients under clopidogrel/dual antiplatelet therapy: to do or not to do? J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2013;22:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boustière C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet G. et al. Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43:445–461. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depta J P, Bhatt D L. Antiplatelet therapy and proton pump inhibition: cause for concern? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27:642–650. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835830b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]