Abstract

Background

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most common congenital bleeding disorder. In women, menorrhagia is the most common bleeding symptom, and is disabling with iron deficiency anemia, high health cost, and poor quality of life. Current hormonal and non-hormonal therapies are limited by ineffectiveness and intolerance. Few data exist regarding Von Willebrand factor (VWF), typically prescribed when other treatments fail. The lack of effective therapy for menorrhagia remains the greatest unmet healthcare need in women with VWD. Better therapies are needed to treat women with menorrhagia.

Methods

We conducted a survey of U.S. hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) and a literature review using medical subject heading (MeSH) search terms “von Willebrand factor,” “menorrhagia,” and “von Willebrand disease” to assess the use of VWF in menorrhagia. Analysis was by descriptive statistics.

Results

Of 83 surveys distributed to HTC MDs, 20 (24.1%) provided sufficient data for analysis. Of 1,321 women with VWD seen during 2011-2014, 816 (61.8%) had menorrhagia, for which combined oral contraceptives, tranexamic acid, and desmopressin were the most common first-line therapies for menorrhagia, while VWF was third-line therapy reported in 13 women (1.6%). Together with data from 88 women from six published studies, VWF safely reduced menorrhagia in 101 women at a dose of 33-100 IU/kg on day 1-6 of menstrual cycle.

Conclusions

This represents the largest VWD menorrhagia treatment experience to date. VWF safely and effectively reduces menorrhagia in women with VWD. A prospective clinical trial is planned to confirm these findings.

Keywords: menorrhagia, von Willebrand disease, von Willebrand factor, women’s health

Introduction

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the single most common congenital bleeding disorder, occurring in 0.1% of the population [1]. VWD is characterized by deficient or defective von Willebrand factor (VWF), a glycoprotein which promotes platelet adhesion to vessel walls after vessel injury. VWF plays a critical role in platelet adhesion and platelet plug formation during primary hemostasis, and serves as a carrier protein for factor VIII [2]. Deficiency of VWF results in mucosal bleeding in the oropharyngeal, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tract [1-3], and, among women, menorrhagia is the most common symptom occurring in 80% or more [3-5]. Menorrhagia is associated with significant morbidity including symptomatic iron deficiency anemia, psychological stress, and reduced quality of life, with excess days lost from work, lifestyle disruptions, and increased health care costs [4-8]. Further, the lack of effective treatment for menorrhagia is an unmet health need among women with bleeding disorders [5, 6, 9, 10]. The recommended non-hormonal agent, tranexamic acid (Lysteda®, TA), is an anti-fibrinolytic agent which reduces menstrual blood loss by 50%, but is limited by nausea [11, 12]. Another non-hormonal agent, desmopressin (DDAVP), which stimulates endothelial release of VWF [3], also reduces menstrual blood loss in 50% [3, 13, 14] but hyponatremia and infusion reactions may complicate its use [13, 15]. Although more convenient, the intranasal form of DDAVP, Stimate®, has less potent effect on VWF release [11, 13, 14, 16-19]. Combined oral contraceptives, which stimulate factor VWF and factor VIII synthesis, are effective in 70% [19], but only 35% of women use these agents for menorrhagia [15] because of headaches and hypertension [14, 15, 19]. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (Mirena®) which releases hormone into the endometrial cavity which produces an anti-fibrinolytic effect that reduces blood loss [20], is limited by weight gain and depression in 20% [20]. Recombinant interleukin-11 (Neumega®, rhIL-11), reduces menorrhagia in over 70% of patients [21] by increasing platelet VWF mRNA expression and VWF synthesis. While mild, reversible fluid retention was observed in some subjects [21], rhIL-11 is no longer manufactured because of toxicity at higher doses used in cancer chemotherapy patients.

Plasma-derived VWF concentrate (Humate-P®, pdVWF) is prescribed for menorrhagia when the above agents fail [3, 4, 13], but it is costly and requires intravenous administration, and little information is available on its use in menorrhagia. Recombinant VWF (Vonicog alfa, rVWF), which is currently under FDA review for treating bleeds in VWD, has higher purity and potency than pdVWF [22], and safely reduces bleeds in severe VWD [23, 24], but few data are available on its use in menorrhagia. Thus, there is a lack of safe, effective treatment for menorrhagia and insufficient data to guide management of menorrhagia in women with VWD.

To meet the goals of Healthy People 2020 to promote safety and prevent complications of blood products [25], we designed a study to determine the feasibility of a prospective, randomized crossover trial to reduce menorrhagia based on a trial concept developed by the Hemophilia and von Willebrand disease Subcommittee of the 2009 National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) State of the Science (SoS) Symposium [26]. As few data exist on VWF to reduce menorrhagia, we designed a survey to determine current treatment practice in U.S. hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs). Further, to determine the published experience with VWF, including pdVWF and rVWF, in the treatment of menorrhagia, we performed a literature review. The results of the survey and literature review are presented herein.

Methods

Survey

As part of a U34 HL-119582 feasibility study to design a future multicenter trial to reduce menorrhagia in women with VWD, the VWD MINIMIZE Trial, we conducted an 8-question survey, distributed by email to U.S. HTCs, utilizing membership lists of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), https://www2a.cdc.gov/ncbddd/htcweb/Main.asp, and the Hemostasis Thrombosis Research Society of North America (HTRS) via site http://htrs.org.

Literature Review

A literature review was performed using PubMed medical subject heading (MeSH) search terms [von Willebrand disease], [menorrhagia], and [von Willebrand factor]. Statistical analysis was by descriptive statistics.

Results

Survey

Of 83 surveys distributed in February 2015 to hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs), 35 HTC MDs responded (42.2%) but only 20 HTC MDs (24.1%) provided sufficient data for analysis (Table 1). Ten of the 15 HTCs (66.6%) with insufficient responses were pediatric HTCs, with none or too few women with VWD to complete the questionnaire. The responding HTC MDs reported a total of 1,321 unique women with type 1 VWD, 18-45 years of age, seen during the 3-year period 2012-2014, of whom 816 (61.8%) had menorrhagia (Table 1). The most common first-line therapy for menorrhagia among surveyed HTCs was COCs, reported by 50.0% of the 20 HTC MDs, followed by the non-hormonal agents, TA in 30.0% and desmopressin (DDAVP) in 20.0%. Overall, including all therapies reported, including first-, second-, and third-line therapies, COCs were prescribed by 90% of the 20 HTC MDs, DDAVP by 85%, TA by 85%, epsilon aminocaproic acid (Amicar®) by 25.0%, and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena® IUD) by 5.0%. Only 4 HTC MDs (20.0%) reported they prescribed VWF concentrate (VWF) for menorrhagia as third-line therapy after other treatments had failed. They reported a total of 13 women, on whom clinical information was available, received VWF at 50 IU/kg for up to 5 days of menstrual bleeding per cycle, with reduction in menorrhagia in all 13 (100%) with no adverse effects.

Table 1.

Survey of Menorrhagia Treatment Practice in U.S. Hemophilia Treatment Centers

| Survey Questions | Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. Women with VWD, 15-45 years (18 HTCs) | 1,321 | ||

| 2014 | 481 (36.4%) | ||

| 2013 | 433 (32.8%) | ||

| 2012 | 408 (30.9%) | ||

| No. Women with VWD and Menorrhagia (18 HTCs) | 816 (61.8%) | ||

| 2014 | 307 (37.6%) | ||

| 2013 | 257 (31.5%) | ||

| 2012 | 252 (30.9%) | ||

| Menorrhagia Treatment (20 HTCs) | 1st-line | 2nd-line | 3rd-Line |

| COC | 14/20 (70.0%) | 2/20 (10.0%) | 2/20 (10.0%) |

| TA | 6/20 (30.00%) | 6/20 (30.0%) | 5/20 (25.0%) |

| DDAVP | 4/20 (20.0%) | 8/20 (40.0%) | 5/20 (25.0%) |

| Mirena ® | 0/20 (0%) | 0/20 (0%) | 1/20 (5.0%) |

| Amicar ® | 0/20 (0%) | 2/20 (10.0%) | 3/20 (15.0%) |

| VWF concentrate | 0/20 (0%) | 0/20 (0%) | 4/20 (20.0%) |

| Mean Percentage Unable to Tolerate Hormones (18 HTCs) | 32.5% (0-50%) | ||

| Barriers to Participation (18 HTCs) | |||

| Insufficient Nursing Staff | 6/18 (33.3%) | ||

| Budget Issues | 6/18 (33.3%) | ||

| Insufficient Resources for IRB preparation | 5/18 (27.8%) | ||

| Other | 5/18 (27.8%) | ||

| Insufficient Patients | 4/18 (22.2%) | ||

| Patient Travel Costs | 1/18 (5.5%) | ||

| Willingness to Participate in VWDMin Trial (16 HTCs) | 16/18 (88.9%) | ||

| Estimate of Potential Number Subjects Participating in Trial (16 HTCs) | 4-5/ HTC over 4-year trial | ||

| 1-2 over 4-year study | 2/16 (12.5%) | ||

| 3-4 over 4-year study | 7/16 (43.7%) | ||

| 5-6 over 4-year study | 4/16 (25.0%) | ||

| 7-8 over 4-year study | 2/16 (12.5%) | ||

| 9-10 over 4-year study | 1/16 (6.2%) | ||

COCs is combined oral contraceptives; TA is tranexamic acid; DDAVP is desmopressin (intravenous or intranasal); Mirena® is levonorgestrel intrauterine system; Amicar® is epsilon aminocaproic acid.

Literature review

The literature search identified six published studies in which VWF concentrate was used to treat menorrhagia in women with VWD, including two prospective clinical trials, two retrospective observational trials, and two observational networks [24, 27-31] (Table 2). The studies reviewed reported VWF concentrate use in patients with any bleeding symptom, from which VWF use by women with menorrhagia was extracted from these broader studies. Of 355 patients with VWD reported in these studies, 88 (24.8%) were women with type 1, 2, or 3 VWD with menorrhagia treated with VWF. Of these, 84 received plasma-derived VWF (pdVWF), 33-95 IU/kg for 1-6 days/cycle, and 4 received recombinant VWF (rVWF), 39-95 IU/kg for 1-2 days/cycle. Together with the 13 women identified in the survey (above), this represents a total of 101 women who have received VWF for menorrhagia, all of whom had reduction in menstrual blood loss, with no reported adverse events.

Table 2.

Literature Review and Survey: VWF in Women with von Willebrand Disease and Menorrhagia

| Study/ Survey | Type Study |

No. VWD

Subjects In Study |

No. VWD with

Menorrhagia VWF-Treated |

Type VWD |

VWF

Product |

VWF Dose

Mean (Range) IU/kg |

VWF Dose

Frequency per Cycle |

Percent Bleed

Reduction* |

Adverse

Events† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature Review | |||||||||

| Abshire et al27 | Retrospective VWD Network |

N = 59 | N = 4 | NA | pdVWF | 39 (38-40) IU/kg | 3/week | 100% | NA |

| Batty et al28 | Retrospective Single-Center Study |

N = 54 | N = 1 | 1, 2, 3 | pdVWF | 45 (40-50) IU/kg | ≥1 days | 100% | Allergic reaction† |

| Berntorp et al29 | Prospective Observational Studies (n=4) |

N = 44 | N = 8 | 1, 3 | pdVWF | 36 (36±12) IU/kg | 1-4 days | 97% | No VTE |

| Holm et al30 | Retrospective Study (n=1); Prospective Trial (n=1) |

N = 105 | N = 9 | 1, 2, 3 | pdVWF | 44 (39-50) IU/kg | 3/week | 100% | NA |

| Gill et al24 | Prospective Phase III Trial |

N = 22 | N = 4 | 1, 2, 3 | rVWF | 43 (39-95) IU/kg | 1-2 days | 100% | NA |

| Miesbach et al31 | Retrospective Observational Study |

N = 71 | N = 62 | 1, 2, 3 | pdVWF | 50 (33-100) IU/kg | 1-6 days | 95% | VTE† |

| SUBTOTAL | N = 335 | N = 88 | 1, 2, 3 | VWF | 43 (33-100) IU/kg | 1 – 6 days | 95-100% | None | |

| Survey | |||||||||

| Ragni et al (this survey) |

Retrospective Survey |

- ** | N = 13 | 1, 2, 3 | pdVWF | 50 U/kg‡ | 5 days | 100% | None |

| TOTAL | N = 101 | 1, 2, 3 | VWF | 43 (33-100) IU/kg | 1-6 days | 95-100% | None | ||

Bleed reduction in the clinical studies overall ranged from 95-100%, which included menstrual bleed reduction, with all subjects reporting menstrual bleed reduction (100%). All surveyed subjects using VWF reported menstrual bleed reduction (100%). Note that all menstrual bleeding responded to treatment with VWF (pdVWF or rVWF).

Adverse events were reported in VWD subjects overall, but none occurred in women with menorrhagia.

The dose and duration were based on available data from four subjects. NA = unavailable; VTE = venous thromboembolism; pd VWF = plasma-derived VWF; rVWF = recombinant VWF.

Note that all subjects in the survey were women with menorrhagia, 13 of whom had clinical information regarding VWF treatment.

Trial Feasibility

Of 20 surveyed HTCs, 16 HTCs (80.0%) indicated they would participate in a phase III trial to reduce menorrhagia comparing rVWF vs. TA, although only 4 HTCs (25.0%) actually currently prescribe VWF for menorrhagia. Barriers to participation in a future phase III trial include insufficient staff at 6 HTCs (33.3%), budget issues at 6 HTCs (33.3%), IRB preparation at 5 HTCs (27.8%), and other issues at 5 HTCs (27.8%), including insufficient patients to enroll at 4 HTCs (22.2%), leading 2 of the HTCs to decline participation in the trial, and patient travel costs at one HTC (6.2%). Barriers to participation were further explored in 30-minute structured interviews with 20 HTC MDs and 20 women with VWD and menorrhagia. Despite the expense and requirement for intravenous access and inability of most subjects to infuse, both patients and MDs found this approach acceptable, given the “lack of response to current therapy,” the “lack of better treatments,” and belief that “replacing the missing VWF will help.” Both MDs and patients were willing to participate, but only with a “nurse to help with infusions.” Neither the MDs nor the patients were willing for study subjects to learn and perform self-infusion for only 1-2 doses for 2 menstrual cycles. Some had concerns about inability to schedule HTC or VNA visit for rVWF infusion on day 1 of menses. The main patient concerns were time and travel required for visits, need for a nurse to do infusions, scheduling infusions the same day menses start, missing work, childcare, and pregnancy risk and teratogenic effects if COCs were stopped. The main MD concerns were finding sufficient eligible patients, pregnancy risk, and the time and cost of setting up contracts, and sufficient funding to cover laboratory, IRB and nursing costs.

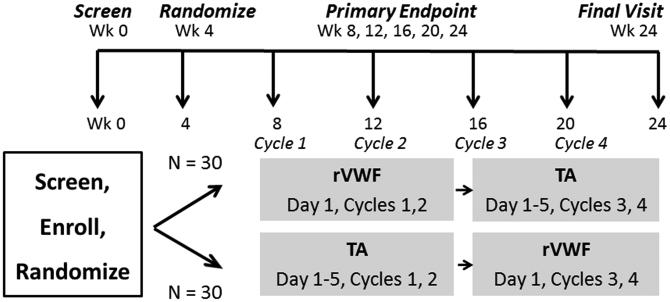

Trial concept and design

We, therefore, propose a phase III multicenter 24-week trial, the VWDMin trial, to compare rVWF with the current non-hormonal treatment of choice, tranexamic acid (TA), to reduce menorrhagia in women with type 1 VWD. Because randomized trials are challenging to accomplish in rare diseases, we worked with experts in rare disease trial design, and chose a randomized crossover design which allows each woman to serve as her own control and receive each drug. Because rVWF is given intravenously and costs more than TA, we hypothesized that in order to be adopted in clinical practice, rVWF would need to be superior to TA and sufficiently acceptable to study subjects to use it after the trial, in order to justify the higher cost and intravenous route. Using as our primary endpoint, the pictorial blood assessment chart (PBAC), a validated measure of menstrual severity, we estimated rVWF would need to reduce PBAC score by 40 points more than TA [Fig.1]. A sample size of 60 achieves 84% power at a type 1 error rate of 0.05 to reject the null hypothesis of no difference when the true difference between changes in PBAC from baseline between drugs is 40 points. This was inflated to 66, as, based on previous studies of TA in VWD, less than a 10% dropout rate is expected [11]. We identified in our 2015 survey 16 HTCs and subsequently 3 non-surveyed HTCs interested in participating in the trial and enroll a minimum of 1 subject per HTC per year or ~19/yr, or ~75 subjects over 4 years, which is ~6% of the total available patients, thereby achieving the sample size, N=66, to complete this trial in 5 years. Thus, the U34 feasibility study indicates the trial is acceptable to MDs and patients, sufficient sites and potential subjects are available to conduct the trial. To promote participation, self-infusion will not be required per MD and patient preference: instead, rVWF will be given on day 1 (or day 2) of menses per patient choice to allow for scheduling by either the HTC nurse or visiting nurse (VNA). Recruitment will exclude those with past thrombosis or current estrogen use to avoid thrombosis risk. Study visits will be scheduled after each of 2 cycles (1 & 2, and 3 & 4) to minimize time and travel burden, and real-time outcomes will be collected monthly with monitoring by HTC nurses. Finally, travel and nursing costs will be compensated; and central IRB submission will be offered to ease HTC staff effort.

Figure 1.

Schema for the Von Willebrand Disease Minimize (VWDMin) Trial.

Innovation

The concept we propose is high-impact, as it addresses the greatest burden and unmet need in women with VWD, the lack of safe, effective treatment for menorrhagia [5, 6, 9, 10]. The trial is innovative as it will evaluate rVWF, which is safe and effective in the treatment of bleeds in VWD, for a new indication, treatment of menorrhagia. Though few data are available to guide treatment, our HTC survey and literature review indicate VWF (pdVWF primarily) over a wide range of doses, safely reduce menorrhagia in 95% of women with VWD. With the anticipated licensure of rVWF in late 2015 and its 1.4-fold prolonged half-life and high purity and potency, we hypothesize a single dose of rVWF will be superior to TA in reducing menorrhagia. Our randomized crossover design is innovative and compelling, as each woman serves as her own control, and the goal of our trial are consistent with Healthy People 2020 objectives to promote safety of existing products [25].

Discussion

This survey and literature review of women with VWD and menorrhagia represent the largest treatment experience with VWF to date. It confirms that COCs are the most common hormonal and TA is the most common non-hormonal first-line therapy prescribed by HTC MDs for menorrhagia, while VWF (pdVWF) is prescribed as a third-line therapy for menorrhagia only after other agents fail. Review of the published studies of VWF used in women with menorrhagia indicates pdVWF reduces menorrhagia in women with VWD with few adverse effects. Our data indicate the most common VWF regimen used to treat menorrhagia by HTC MDs is 50 U/kg for up to 5 days, although there is wide variability in dose and frequency prescribed by HTC MDs, 33-100 U/kg over 1-6 days. The four women treated with rVWF were participants in a phase III trial of a new recombinant VWF [24], currently under review by the FDA, and received a median dose of 43 U/kg for 1-2 days for menorrhagia. As compared with pdVWF, rVWF has negligible transmissible agent risk and similar potency, platelet binding, collagen binding, and platelet adhesion [22], suggesting it might be a potential new therapeutic for menorrhagia. Whether the modest 1.4-fold increase in rVWF half-life as compared with pdVWF [24] will allow for once per cycle dosing with extended protection is unknown. The higher purity and specific activity of rVWF as compared with pdVWF may also contribute to greater function [22-24]. Clearly, it will be critical to establish acceptability of rVWF as it requires intravenous infusion and would be anticipated to be more costly than other non-hormonal therapies.

There are a number of limitations of retrospective surveys, including recall bias, selection bias, short follow-up, lack of data verification, and representativeness of a few HTCs to all HTCs. Further, the assessment of menorrhagia by subjective response, while routinely used by gynecologists in practice, is less objective than validated measures of blood loss severity, such as the pictorial blood assessment chart (PBAC) [32], or surrogate markers such as improvement in hematocrit and iron stores, or quality-of-life measures which have been used to assess treatment response to therapy [11, 21]. Finally, while data from surveys and reviews cannot replace clinical trials for determining safety and efficacy of therapeutic agents, they complement existing information and confirm the need for prospective trials of new agents to treat menorrhagia in women with VWD.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate while VWF concentrates are typically prescribed as third-line therapy after other agents have failed, they safely reduce menorrhagia in the majority of women with von Willebrand disease. The optimal dose and duration of therapy, objective quantitation of blood loss reduction, and satisfaction with this more invasive and potentially more expensive therapeutic agent remain to be established. We believe our findings provide support for a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial to determine the safety and efficacy of recombinant von Willebrand factor when used with tranexamic acid, the current standard non-hormonal therapy, compared with tranexamic acid alone in reducing menorrhagia in women with von Willebrand disease.

Acknowledgments

M. Ragni receives research funding from Alnylam, Baxalta, Biogen, Biomarin, CSL Behring, Dimensions, Genentech/Roche, Pfizer, Shire, SPARK, and serves on the advisory boards of Alnylam, Baxalta, Biogen, and Biomarin. L. Malec receives research funding from Biogen. A. James receives research funding from CSL Behring. C. Kessler receives research funding from Grifols and Octapharma; and honoraria for advisory board activities from Grifols, Baxalta, and Octapharma. B. Konkle receives research support from Baxalta, and serves as a consultant for Baxalta and CSL Behring. P. Kouides receives honoraria as a member of an advisory board CSL Behring, and serves as a consultant to Baxalta. A. Neff serves on advisory boards for Baxter, CSL Behring, and NovoNordisk. C. Philipp receives research funding from Baxalta and Novonordisk; and serves on Advisory Boards for Baxalta and NovoNordisk. D. Brambilla has research funding from NIH/NHLBI.

Support:

The work was funded by Grant NHLBI grant U34-HL119582 from the Heart Blood and Lung Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Footnotes

Addendum

We thank T. Coyle, J. Davis, A. Drygalski, S. Jobe, P. Kuriakose, A. Ma, E. Majerus, D. Nance, T.F. Wang, and H. Yaish for providing data for this study.

Author Contribution

M. Ragni and N. Machin designed the study, performed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. L. Malec and A. James contributed to design of the study, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. C. Kessler, B. Konkle, P. Kouides, A. Neff, and C. Philipp performed the research, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. D. Brambilla interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Disclosure

N. Machin reports no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Dini E. Epidemiologic investigation of the prevalence of von Willebrand disease. Blood. 1987;69:454–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadler JE, Budde U, Eikenboom JCJ. Update on the pathophysiology and classification of von Wilebrand disease: a report of the Subcommittee on von Willebrand Factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2103–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols WL, Hultin MB, James AH, Manco-Johnson MJ, Montgomery RR, Ortel TL, Rick ME, Sadler JE, Weinstein M, Yawn BP. Von Willebrand Disease (VWD): Evidence-based diagnosis and management guidelines, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Expert Panel Report (USA) Haemophilia. 2008;14:171–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ragni MV, Bontempo FA, Cortese-Hassett AL. von Willebrand disease and bleeding in women. Haemophilia. 1999;5:313–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James A, Ragni MV, Picozzi V. ASH Special Educational Symposium: Bleeding Disorders in Premenopausal Women: Another Public Health Crisis for Hematology. Hematology. 2006;474:85. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . NICE Clinical guidelines 44: heavy menstrual bleeding. National Health Service; London (UK): 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadir RA, Edlund M, von Mackensen S. The impact of menstrual disorders on quality of life in women with inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2010;16:832–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallberg L, Milsson L. Determinants of menstrual blood loss. Scand J Lab Invest. 1996;16:244–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James AH. Women and bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2010;16(Suppl 5):160–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACOG . Management of Anovulatory Bleeding. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouides PA, Byams VR, Philipp CS, Stein SF, Heit JA, Lukes AS, Skerrette NI, Dowling NF, Evatt BL, Miller CH, Owens S, Kulkarni R. Multisite management study of menorrhagia with abnormal laboratory haemostasis: a prospective crossover study of intranasal desmopressin and oral tranexamic acid. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:212–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tosetto A, Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Goodeve A, Federici AB, Batlle J, Meyer D, Fressinaud E, Mazurier C, Goudemand J, Eikenboom J, Schneppenheim R, Budde U, Ingerslev J, Vorlova Z, Habart D, Holmberg L, Lethagan S, Pasi J, Hill F, Peake I. A quantitative analysis of bleeding symptoms in type 1 von Willebrand disease: results from a multicenter European study (MCMDM-1 VWD) J Thromb Hemost. 2006;4:766–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannucci PM. Desmopressin in the treatment of bleeding disorders: the first 20 years. Blood. 1997;90:2515–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlesinger KW, Rinder HM, Ragni MV. Women with bleeding disorders, in Menstrual Disorders. In: Ehrenthal DB, Hoffman MK, Hillard PJ, editors. Women’s Health Book Series. American College of Physicians/ American Society of Internal Medicine; Philadelphia: 2006. pp. 171–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byams VR, Baker J, Brown DL, Gill JC, Grant AM, James AH, Konkle BA, Kulkarni R, Maahs J, Malone M, McAlister SO, Nugent D, Philipp CS, Soucie JM, Stang E, Kouides PA. Baseline characteristics of females with bleeding disorders receiving care in the U.S. HTC Network. National Conference on Blood Disorders in Public Health. 2010;E3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kadir RA, Lee CA, Sabin CA, Pollard D, Economides DL. DDAVP nasal spray for treatment of menorrhagia in women with inherited bleeding disorders: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study. Haemophilia. 2002;8:787–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lethagen S. Desmopressin in the treatment of women’s bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 1999;5:233–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose SS, Faiz A, Miller CH, Saidi P, Philipp CS. Laboratory response to intranasal desmopressin in women with menorrhagia and platelet dysfunction. Haemophilia. 2008;14:571–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster PA. The reproductive health of women with von Willebrand disease unresponsive to DDAVP: results of an international survey (ISTH) Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:784–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingman CE, Kadir RA, Lee CA, Economides DL. The use of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for treatment of menorrhagia in women with inherited bleeding disorders. BJOG. 2004;111:1425–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ragni MV, Jankowitz RC, Merricks EP, Kloos M, Nichols TM. Recombinant interleukin 11 (Neumega®) in women with von Willebrand disease and menorrhagia. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:641–45. doi: 10.1160/TH11-04-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turecek PL, Schrenk G, Rottensteiner H, Varadi K, Bevers E, Lenting P, Ilk N, Sleytr UB, Ehrlich HJ, Schwarz HP. Structure and function of a recombinant von Willebrand factor drug candidate. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:510–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannucci PM, Kempton C, Miller C, Romond E, Shapiro A, Birschmann I, Ragni MV, Gill JC, Yee TT, Klamroth R, Wong WY, Chapman M, Engl W, Turecek PL, Suiter TM, Ewenstein BM. Pharmokinetics and safety of a novel recombinant human von Willebrand factor manufactured with a plasma-free method: a multicenter prospective clinical trial. Blood 2. 013;122:648–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill J, Castaman G, Windyga J, Kouides P, Ragni M, Leebeek F, Obermann-Slupetzky Chapman M, Fritsch S, Pavlova BG, Presch I, Ewenstein B. Safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of a recombinant von Willebrand factor in patients with severe von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2015;126:2038–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medical Product Safety Healthy People 2020. Accessed August 21, 2015, http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/blood-disorders-and-blood-safety.

- 26.Cines DB, Blajchman MA, High KA, Bussell JB, for the State-of-the-Science Symposium Hemostasis-Thrombosis Committee Clinical trial opportunities in Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Proceedings of the NHLBI State-of-the-Science Symposium. Am J Med. 2012;87:237–38. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abshire TC, Federici AB, Alvarez MT, Bowen J, Carcao MD, Gill JC, Key NS, Kouides PA, Kurnik K, Lail AE, Leebeek FWG, Makris M, Mannucci PM, Winikoff R, Berntorp E. Prophylaxis in severe forms of von Willebrand disease: results from the von Willebrand Disease Prophylaxis Network (VWD PN) Haemophilia. 2013;19:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batty P, Chen YH, Bowles L, Hart DP, Platton S, Pasi KJ. Safety and efficacy of a von Willebrand factor/factor VIII concentrate (Wilate®): a single centre experience. Haemophilia. 2014;20:846–53. doi: 10.1111/hae.12496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berntorp E, Windyga J, The European Wilate Study Group Treatment and prevention of acute bleedings in von Willebrand disease – efficacy and safety of Wilate®, a new generation von Willebrand factor/factor VIII. Haemophilia. 2009;15:122–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm E, Abshire TC, Bowen J, Alvarez MT, Bolton-Maggs P, Carcao M, Federici AB, Gill JC, Halijmeh S, Kempton C, Key NS, Kouides P, Lail A, Landorph A, Leebeek F, Makris M, Mannucci P, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Nugent D, Valentino LA, Winikoff R, Berntorp E. Changes in bleeding patterns in von Willebrand disease after institution of long-term replacement therapy: results from the von Willebrand Disease Prophylaxis network. Blood Coag Fibrinolysis. 2015;26:383–88. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miesbach W, Krekeler S, Wolf Z, Seifried E. Clinical use of Haemate® P in von Willebrand disease: A 25-year retrospective observational study. Thromb Res. 2014;135:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid PC, Coker A, Coltart R. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart: a validation study. BJOG. 2000;107:320–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]