Abstract

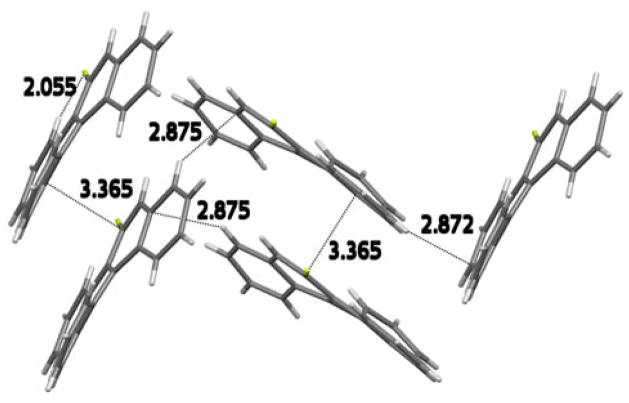

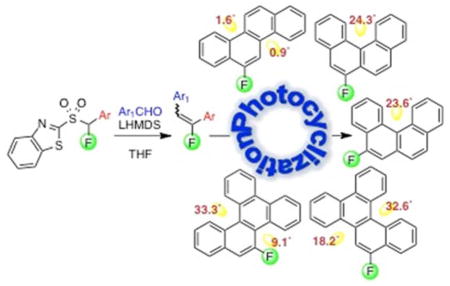

A modular synthesis of regiospecifically fluorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) is described. 1,2-Diarylfluoroethenes, synthesized via Julia-Kocienski olefination (70–99% yields), were converted to isomeric 5- and 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene, 5-and 6-fluorochrysene, and 9- and 10-benzo[g]chrysene (66–83% yields) by oxidative photocyclization. Photocyclization to 6-fluorochrysene proceeded more slowly than conversion of 1-styrylnaphthalene to chrysene. Higher fluoroalkene dilution led to a more rapid cyclization. Therefore, photocyclizations were performed at higher dilutions. To evaluate the effect of fluorine atom on molecular shapes, X-ray data for 5- and 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene, 6-fluorochrysene, 9- and 10-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene, and unfluorinated chrysene as well as benzo[g]chrysene were obtained and compared. The fluorine atom caused a small deviation from planarity in the chrysene series, decreased nonplanarity in the benzo[c]phenanthrene derivatives, but its influence was most pronounced in the benzo[g]chrysene series. A remarkable flattening of the molecule was observed in 9-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene, where the short 2.055 Å interatomic distance between bay-region F-9 and H-8, downfield shift of H-8, and a 26.1 Hz coupling between F-9 and C-8 indicate a possible F-9··· H-8 hydrogen bond. Also, in 9-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene, stacking distance is short at 3.365 Å and there is an additional interaction between the C-11–H and C-10a of a nearby molecule that is almost perpendicular.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Fluoroaromatic compounds are of interest in diverse fields, such as materials and supramolecular chemistry, environmental analyses, and biological studies. As examples, applications of fluoroaromatic compounds can be found in liquid crystalline materials, organic light-emitting diodes, and organic field-effect transistors.1,2 Recently, polymers containing fluorinated aromatic building blocks have shown improved performance of organic solar cells.2d Use of fluoroaromatics as internal standards in GC-MS analyses has been reported.3 In the area of chemical carcinogenesis by polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs),4–10 fluorinated PAHs have frequently been used in carcinogenicity studies.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are the products of activities of modern society and are common contaminants in the environment.4 PAHs that contain a bay or fjord region are known to undergo metabolic activation via a monoxygenase-epoxide hydrolase pathway, where angular-ring diol epoxides are formed.5 The electrophilic diol epoxides covalently bind to DNA ultimately resulting in adverse biological effects.6 An alternate metabolic pathway involves formation of reactive, redox active o-quinones that can lead to DNA damage.7 Fluorine is a powerful modulator of biological activity and introduction of fluorine into a PAH is known to significantly alter its biological activity. For example, 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene (6-F-BcPh) showed increased tumorigenicity as compared to benzo[c]phenanthrene (BcPh),8 whereas 6-fluorobenzo[a]pyrene (6-F-BaP) showed decreased tumorigenicity as compared to benzo[a]pyrene (BaP).9 In the latter case this is attributed to fluorine-atom-induced conformational change in the metabolite.9b Studies on the effect molecular distortion of PAHs can have on metabolic activation and DNA binding have been conducted using 1,4-difluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene as a model compound.10 In order to better understand the structure-activity relationships on molecular-genetic level, availability of sufficient quantities of regiospecifically fluorinated PAHs is critical.

Our present goal was to explore a convenient, general route to regiospecifically fluorinated PAHs, via the use of fluorinated building blocks, for potential applications in diverse fields. To date, various methods have been used for the introduction of fluorine into polycyclic aromatic systems, such as diazotization-fluorination,11 direct electrophilic substitution,12 bromine-fluorine exchange,13 and cyclizations of smaller fluorinated building blocks.14 Photocyclizations of stilbene like derivatives with appropriate fluorine atom-substituted and often commercially available aryl moieties are known,10,15 and recently photodehydrofluorination approach to polyfluorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons has been reported.15e Although stilbene can be cyclized readily to phenanthrene, it has been reported that α-fluorostilbene could not be cyclized to the fluoro analogue.15a Introduction of an additional ring increases the feasibility of photocyclization, and β-fluoronaphthyl styrene has been converted to 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene.11a Key to this approach was a substrate-dependent regioselective bromofluorination of β-fluoronaphthyl styrene, followed by elimination, and photochemical closure. On the other hand, synthesis of the isomeric 5-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene required a completely different approach.11a Transition-metal-catalyzed introduction of fluorine atom into aromatics has been the focus of recent research and in the context of PAHs, synthesis of 4-aza-10-fluorophenanthrene,16a 9-fluorophenanthrene,16b 5-and 6-fluorochrysenes, and fluorinated phenacenes16c has been reported. Several fluorinated PAHs (F-PAHs) were synthesized via indium(III)-catalyzed cyclization of aryl- and cyclopentene-substituted 1,1-difluoroallenes, followed by ring expansion and dehydrogenation.17 Whereas the latter two methods16c,17 are mechanistically interesting, one potential limitation is a substrate-dependent formation of isomeric monofluoro PAHs.

We describe herein a general route to a series of regiospecifically fluorinated aryl hydrocarbons. To our knowledge, the use of a fluoro Julia olefination to regiospecifically place a fluorine atom followed by photocyclization has not been studied to date.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

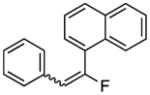

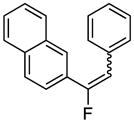

We have been involved with the use of the modified Julia-Kocienski olefination18 for novel approaches to variously functionalized regiospecifically fluorinated olefins,19,20 including 1,2-diarylfluoroethenes.21 Since photodehydrocyclizations of a variety of 1,2-diarylethenes to several classes of PAHs and helicenes have been well documented,22 we reasoned that photocyclization of regiospecifically substituted 1,2-diarylfluoroethenes could offer a simple, modular approach to regiospecifically fluorinated PAHs. Importantly, although 1,2-diarylfluoroethenes are formed as E/Z mixtures in Julia-Kocienski reactions, the alkene geometry is not critical to the photocyclization, with alkene isomerization occurring under the reaction conditions. Herein, we present a new approach to regiospecifically fluorinated PAHs via a tandem fluoro Julia olefination and oxidative photocyclization. Figure 1 shows a retrosynthetic approach to the modular synthesis of fluorinated PAHs. Also shown in Figure 1 are structures of 5- and 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene (5-F-BcPh and 6-F-BcPh), 5- and 6-fluorochrysene (5-F-Ch and 6-F-Ch), and 9- and 10-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene (9-F-BgCh and 10-F-BgCh), the targets of our approach.

FIGURE 1.

Retrosynthetic route to regiospecifically fluorinated PAHs via Julia olefination and oxidative photocyclization, and structures of the targets selected for this work.

Previously we have reported high-yield synthesis of regiospecifically fluorinated stilbene-like derivatives via the Julia-Kocienski olefination.21 For this, fluorobenzyl heteroaryl sulfones are required. We have previously developed a general synthesis via heterogeneous metalation fluorination of heteroaryl benzyl sulfones and, more specifically the 1,3-benzothiazol-2-ylsulfonyl (BT-sulfonyl) derivatives.21 For the purpose of this study, fluoro(phenyl)methyl (2a),21 fluoro(1-naphthyl)methyl (2b),20b and fluoro(2-naphthyl)methyl (2c)21 1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl sulfones were synthesized (Scheme 1), as described. Fluoro(phenanthren-9-yl)methyl 1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl sulfone (2d) was prepared by analogous protocols.20b,21 Fluorination of sulfones 1a–d using our heterogeneous conditions (LDA, toluene, and addition of solid NFSI) afforded fluorinated sulfone derivatives 2a–d in high 87–93% yields. The yields of the critical fluorination step and 19F NMR data of fluoro sulfones 2a–d are displayed in Scheme 1.

SCHEME 1.

Synthesis of (Aryl)fluoromethyl BT Sulfones 2a–d

With sulfone reagents 2a–d, synthesis of regiospecifically fluorinated vinyl compounds was performed via a modified Julia olefination. Condensation of fluorinated BT-sulfones 2a–d with appropriate aldehydes under basic conditions (LHMDS, THF, 0 °C) afforded the E/Z monofluoro diarylethylenes (Table 1), the key intermediates for the photocyclization. Initially, photocyclization to 6-F-Ch (3) under Katz conditions,23 was performed on a 1 g scale (4.0 mM concentration) of the fluoroalkene (E:Z 74%:26%), and 6-F-Ch was isolated in 74% yield. However, the reaction was extremely slow and it took 112 h to reach completion. Progress of the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR and is depicted in Figure 2. Upon conducting the photochemical ring closure at a higher dilution (1 mM) of the fluoroalkene, the reaction was complete within 8 h and 6-F-Ch (3) was isolated in a comparable 72% yield. Thus, it appears that the overall reaction time is dependent upon substrate concentration, but a longer reaction time does not have a detrimental effect on the yield. In this regard, Katz et al. have shown that in reactions with stoichiometric iodine, a higher substrate concentration led to lower conversion and recovery of starting material, whereas excellent conversion was obtained with increased substrate dilution, in a comparable reaction time.23

TABLE 1.

Synthesis of Fluoroalkenes and the Regiospecifically Fluorinated PAHs

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | sulfone; Ar1 CHO: Ar1 = | fluoroalkene intermediate: yield,a E:Z ratio;b 19F NMR datac | F-PAHs 3–8: yield;a 19F NMR datac |

| 1 |

2a;

|

99%, 2.8:1; δ −100.0 ppm (d, 3JFH = 21.4 Hz, E-isomer); − 115.6 ppm (d, 3JFH = 39.7 Hz, Z-isomer) |

3: 72%; δ −123.8 ppm (d, J = 15.3 Hz) |

| 2 |

2b;

|

81%, 2.9:1; δ −84.4 ppm (d, 3JFH = 18.3 Hz, E-isomer); − 95.2 ppm (d, 3JFH = 39.7 Hz, Z-isomer) |

4: 71%; δ −111.8 ppm (br dt,d J = 15.7, 3.3 Hz) |

| 3 |

2a;

|

99%, 2.9:1; δ −96.2 ppm (d, 3JFH = 18.3 Hz, E-isomer); − 114.4 ppm (d, 3JFH = 39.7 Hz, Z-isomer) |

5: 66%; δ −125.4 ppm (d, J = 9.2 Hz) |

| 4 |

2c;

|

76%, 2.75:1; δ −96.6 ppm (d, 3JFH = 21.4 Hz, E-isomer); − 114.9 ppm (d, 3JFH = 39.7 Hz, Z-isomer) |

6: 83%; δ −125.8 ppm (d, J = 12.2 Hz) |

| 5 |

2a;

|

70%, 3.1:1; δ −100.3 ppm (d, 3JFH = 21.4 Hz, E-isomer); −115.2 ppm (d, 3JFH = 36.6 Hz, Z-isomer) |

7: 77%; δ −124.3 ppm (d, J = 12.2 Hz) |

| 6 |

2d;

|

89%, 2.88:1; δ −85.0 ppm (d, 3JFH = 21.4 Hz, E-isomer); − 95.3 ppm (d, 3JFH = 36.6 Hz, Z-isomer) |

8: 73%; δ −114.6 ppm (dd, d J = 15.1, 2.3 Hz) |

Yields are of isolated and purified products.

E/Z olefin ratios in the crude reaction mixtures were determined by 19F NMR prior to isolation.

Obtained at 282 MHz in CDCl3, with CFCl3 as an internal reference.

Obtained with resolution enhancement.

FIGURE 2.

Formation of 6-F-Ch (% conversion in green bars and the E/Z fluoroalkene ratio in orange bars). Reaction was monitored by 19F NMR.

For comparison, the unfluorinated 1-styrylnaphthalene (E:Z 97%:3%) was subjected to photocyclization to form chrysene on a 1 g scale (4.38 mM concentration). Progress of the reaction, depicted in Figure 3, was monitored by 1H NMR, by comparing key resonances of the cis- and the trans-alkene, to an aromatic resonance of chrysene at 8.80 ppm (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H). Key resonances of the alkene were the vinylic24 H (=C-Hcis: 6.85 ppm, d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1 H; =C-Htrans: 7.17 ppm, d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H) and aromatic24 H (Ar-H of cis-alkene: 8.09 ppm, br d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H; Ar-H of trans-alkene: 8.24 ppm, d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H). In this case, conversion to chrysene was 97% complete within 1 h.

FIGURE 3.

Formation of chrysene (% conversion in green bars and the E/Z alkene ratio in orange bars).

UV spectra of the alkene mixtures that were subjected to photocyclization (fluoroalkene E/Z 3:1 and 1-styrylnaphthalene E:Z ≥ 97%:3%) were compared, each at 2.3 × 10−5 M concentration. The spectrum of the fluoroalkene mixture shows a hypsochromic shift of both, long- and short-wavelength absorption maxima, as compared to the protio analogue. The long-wavelength absorption of the E/Z fluoroalkenes shows hypochromicity, whereas the short-wavelength absorption shows hyperchromicity as compared to the protio olefins (see the Supporting Information).

Photocyclization to 6-F-Ch in benzene, using a catalytic amount of iodine in air was also attempted on a 0.460 g scale (1.85 mM concentration). After 8 hours, analysis of the reaction mixture by 19F NMR showed resonance corresponding to 6-F-Ch (29%) and E/Z fluoroalkene resonances (71%). Further irradiation resulted in consumption of the fluoroalkene after 42 hours, but only a trace of 6-F-Ch was isolated, and other unidentified products were formed. Photocyclization to 6-F-Ch in acetone as solvent, under a nitrogen atmosphere,25 did not proceed, and the starting material was recovered.

In summary, these results indicated: (a) higher fluoroalkene dilution gave a faster photocyclization, (b) conditions involving catalytic iodine and air were not usable, (c) use of Katz-modified23 photocyclization proceeded well, and (d) photocyclization in acetone under nitrogen was ineffective. On the basis of these results, photocyclizations were performed in a Hanovia immersion-type photoreactor using a 450 W Hg vapor lamp and a quartz filter. Reactions were conducted in benzene as solvent, with a stoichiometric amount of iodine as the oxidant and propylene oxide as the HI sponge. Under these conditions F-PAHs 4–8 were obtained in 66–83% yields. Table 1 shows the olefination partners, condensation yields, E/Z olefin ratios, and 19F NMR data of intermediate fluoroalkenes, as well as the final photocyclization products along with their yields. Notably, 19F NMR data of PAHs 3–8 (Table 1) showed that the fluorine resonance appears ca. 10 ppm more downfield when it resides in the hydrocarbon bay region (entries 2 and 6), as opposed to when it is not present in a bay region (compare data of PAHs 4 and 8 to those of 3, 5, 6, and 7).

The final fluorinated products 3–8 were crystallized for analysis by X-ray crystallography. While this work was in progress, independent syntheses and X-ray data for compounds 3 and 4 were published.17 In the present work, data analysis of compound 3 originates from the crystallographic information we obtained, whereas the analysis of data for compound 4 comes from its published crystallographic data.17

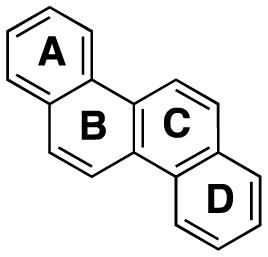

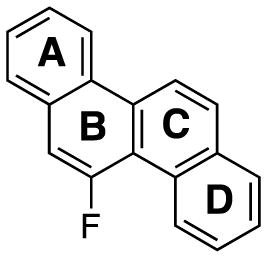

In order to gain insight into the influence of the fluorine atom on the shapes of these molecules, angles between the rings of the PAHs were compared to the corresponding unfluorinated PAH (Tables 2–4). Since the X-ray structures of the unfluorinated chrysene (Ch) and benzo[g]chrysene (BgCh) were unknown, we also obtained data on these two PAHs (both are commercially available and can also be synthesized via the Julia olefination-photocyclization approach presented here, using unfluorinated alkenes). Crystallographic structures obtained in this work are shown in Figure 4, and details follow.

TABLE 2.

Angles between the Four Planes of Ch, 6-F-Ch, and 5-F-Cha

| angle between |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| A, B | 0° | 0.9° | 1.4° |

| A, C | 0° | 1.6° | 1.1° |

| B, C | 0° | 0.8° | 3.7° |

| B, D | 0° | 0.9° | 1.0° |

| C, D | 0° | 0.4° | 2.2° |

| A, D | 0° | 1.8° | 5.9° |

|

| |||

| estimated error e.s.d | 0° | 0.4° | 0.1° |

Angles between the planes of 5-F-Ch were calculated from the published X-ray information.17

FIGURE 4.

Crystal structures of PAHs and F-PAHs obtained in this work (C, gray; H, white; F, green).

In the chrysene series (Table 2), Ch is completely planar (0° angle between the four planes), and 6-F-Ch (3) shows a small deviation from planarity, with angles between the planes in the range of 0.4–1.8°. Deviation from planarity for 5-F-Ch (4)17 with a bay-region fluorine atom is larger, with angles between the planes in the range of 1.0–5.9°. The overall distortion from planarity (angle between planes A and D) is 1.8° for 6-F-Ch (3), and 5.9° for 5-F-Ch (4).

Although our structure of 6-F-Ch (3) is the same as that published by Fuchibe et al.,17 our analysis of its crystal structure differed in the treatment of the hydrogen atom fluorine atom positions. All hydrogen atom positions were found and refined from our X-ray data, whereas Fuchibe et al.17 calculated the idealized hydrogen atom positions. That fluorine exhibits positional disorder is well-established,26 and indeed, for 6-F-Ch (3) the fluorine atom occurs 78% of the time at the C-6 (major occupancy position) and 22% of the time at the C-12 position. The remainder of the time, at these positions, fluorine is replaced by a hydrogen atom. The C–F bond length of the major occupancy fluorine is 1.343(3) Å while the C–F bond for the minor occupancy fluorine, as expected, is in between a C–H and C–F bond length, 1.146(9) Å. From our experimentally determined hydrogen atom positions, we can see two dominant intermolecular interactions, a strong stacking interaction and a C-8–H···F interaction (Figure 5). The stacking interaction of 3.421(5) Å is between the planes of 6-F-Ch (3) molecules. The second interaction is the hydrogen bond between the major occupancy F (at C-6) and the H-8–C-8 of a neighboring molecule at 2.516(9) Å that is perpetuated throughout the crystal structure. This C–H···F distance is shorter than the calculated distance of 2.619 Å from the published crystal structure having calculated hydrogen atom positions of C-6–F···H-8. We also see additional intermolecular interactions between C–H and ring carbon atoms of 2.844 Å, 2.895 Å, and 2.889 Å. These are approximately perpendicular (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Intermolecular interactions in the X-ray crystal structure of 6-F-Ch (3) (our data).

In BcPh series, the overall distortion from planarity in 5-F-BcPh (5) and in 6-F-BcPh (6) is smaller than in the parent hydrocarbon (Table 3 and Figure 4). This is reflected in the angle between rings A and D forming the fjord region and in the angle between rings A and C. The angle between rings A and D is 26.7° in BcPh, and decreases to 24.3° and 23.6° in 6-F-BcPh (6) and 5-F-BcPh (5), respectively. The angle between rings A and C is 18.1° in BcPh, 16.2° in 6-F-BcPh (6), and 14.2° in 5-F-BcPh (5).

TABLE 3.

Angles between the Four Planes of Unfluorinated and Fluorinated BcPh

| angle between |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| A, B | 10.3° | 9.4° | 8.2° |

| A, C | 18.1° | 16.2° | 14.2° |

| B, C | 7.9° | 6.8° | 7.1° |

| B, D | 16.6° | 15.2° | 17.0° |

| C, D | 8.8° | 8.8° | 9.9° |

| A, D | 26.7° | 24.3° | 23.6° |

|

| |||

| estimated error e.s.d | 0.1° | 0.2° | 0.2° |

The most pronounced effect fluorine atom has on the molecular shape is in the benzo[g]chrysene series. Here again, the overall distortion from planarity decreases upon fluorine atom substitution (Table 4 and Figure 4). The angle between rings A and D forming the fjord region is 36.0° in the parent BgCh, and this decreases to 32.6° in 10-F-BgCh (7) and to 33.3° in 9-F-BgCh (8). However, the angles between rings B and E, which form a bay region, show the most remarkable difference. The angle between rings B and E is 20.1° in the parent hydrocarbon, decreasing to 18.2° in 10-F-BgCh (7), and this decreases dramatically to 9.2° in 9-F-BgCh (8). In 9-F-BgCh (8), the fluorine atom resides in the bay region, and the interatomic distance between F-9 and the bay-region H-8 is 2.055 Å, with a C–H···F angle of 128.73°, which suggests a possible hydrogen bond.27,28 In the 1H NMR spectrum of 9-F-BgCh (8), H-8 appears at 9.07 ppm, and is shifted downfield as compared to H-8 in unsubstituted BgCh, where it appears at 8.63 ppm.29 The bay-region H-8 and F-9 resonances in compound 8 show a small ~2 Hz coupling (2.3 and 2.2 Hz, respectively). In the 13C NMR spectrum of 9-F-BgCh (8), the C-8 resonance appears at 128.0 ppm, as a doublet with a J = 26.1 Hz. This is a typical value for a scalar two-bond C–F coupling constant. The downfield shift of the H-8 proton, its coupling to F-9, and the large C-8–F coupling constant further support possible hydrogen bonding between F-9 and H-8.27,28 It is plausible, therefore, that the tendency towards F–H bonding is responsible for the planarization in B-, C-, E-ring region, decreasing the angles between these rings in 9-F-BgCh (8). The hydrogen atom positions in the 9-F-BgCh structure were calculated. Additional strong intermolecular interactions include the short stacking distance at 3.365 Å and two additional short almost perpendicular interactions: one at 2.875 Å between the C-11–H and C-10a of a nearby molecule and another at 2.872 between C-4–H and C-6 of a neighboring molecule (Figure 6).

TABLE 4.

Angles between the Five Planes of Unfluorinated and Fluorinated BgCh

| angle between |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| A, B | 11.5° | 12.0° | 9.7° |

| A, C | 25.7° | 21.5° | 22.5° |

| B, C | 14.2° | 9.6° | 12.°8 |

| B, D | 24.6° | 20.9° | 23.7° |

| C, D | 10.7° | 11.4° | 11.1° |

| B,E | 20.1° | 9.2° | 18.2° |

| C,E | 8.6° | 4.5° | 8.5° |

| D,E | 11.9° | 12.8° | 12.7° |

| A,E | 31.1° | 20.1° | 27.2° |

| A, D | 36.0° | 32.6° | 33.3° |

|

| |||

| estimated error e.s.d | 0.1° | 0.1° | 0.1° |

FIGURE 6.

Intermolecular interactions in the X-ray crystal structure of 9-F-BgCh (8).

In 5-F-Ch (4), which also has a fluorine atom residing in the bay region, the interatomic distance between F-5 and the bay-region H-4 is 2.069 Å, with a C–H···F angle of 126.80°, again suggestive of intramolecular hydrogen bonding. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 5-F-Ch (4) show similar features to those of 9-F-BgCh (8). In the 1H NMR spectrum of 5-F-Ch (4), the bay-region H-4 appears at 9.25 ppm, and is downfield shifted as compared to H-4 in unsubstituted chrysene (Ch), which appears at 8.79 ppm.30 The bay-region H-4 and F-5 resonances in compound 4 show a ~3 Hz coupling (2.8 and 3.3 Hz, respectively). In the 13C NMR spectrum of 5-F-Ch (4), the bay-region C-4 appears at 128.0 ppm, as a doublet, with a large 26.6 Hz coupling constant with the fluorine atom.

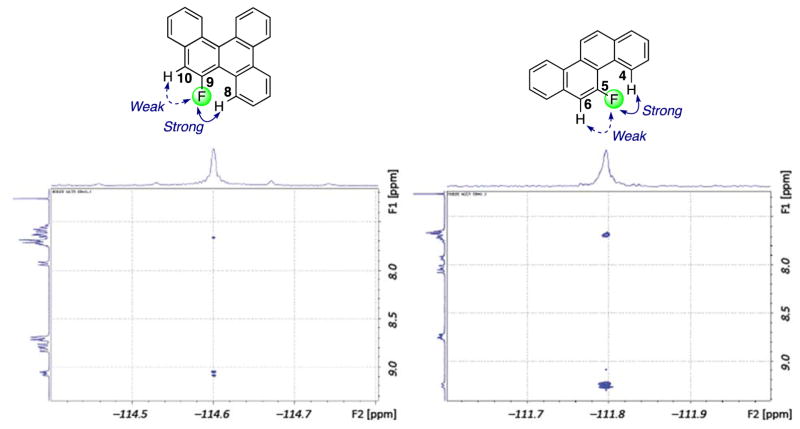

Through-space spin-spin coupling has been a subject of research for several years now.31 In previous studies, other investigators have reported comparable NMR spectral features for PAHs containing a bay-region fluorine atom. Mallory et al. suggested through-space H–F coupling interactions in 4-fluorophenanthrene, where a 2.6 Hz H–F coupling was observed between the bay-region fluorine atom and the bay-region H-5.32 In the present case, resonances of bay-region H-8 and F-9 of compound 8 show a similar small ~2 Hz coupling, whereas resonances of bay-region H-4 and F-5 of compound 4 show a ~3 Hz coupling. Sardella et al. studied 1H and 13C NMR spectra of PAHs containing a bay-region fluorine atom.33 Similar to what we have observed for compounds 8 and 4, a C–F coupling of 24.9 Hz across the bay region was reported, and through-space C–F coupling interactions were suggested.33

We also obtained 1H–19F HOESY spectra of 9-F-BgCh (8, left, Figure 7) and 5-F-Ch (4, right, Figure 7). The HOESY spectrum of 9-F-BgCh (8) shows an intense interaction between the fluorine atom and the H-8 resonance at 9.07 ppm, in support of C-8–H···F hydrogen bonding. The weaker interaction is between the fluorine atom and the H-10 resonance at 7.67 ppm. The HOESY spectrum of 5-F-Ch (4) shows an intense interaction between the fluorine atom and the H-4 resonance at 9.25 ppm, in support of C-4–H···F hydrogen bonding. The weaker interaction is between the fluorine atom and the H-6 resonance at 7.68 ppm.

FIGURE 7.

1H–19F HOESY spectra of 9-F-BgCh (8, left) and of 5-F-Ch (4, right).

CONCLUSIONS

1,2-Diarylfluoroethenes, which were synthesized via Julia-Kocienski olefination, were subjected to oxidative photocyclization to yield regiospecifically substituted monofluoro PAHs. Photocyclizations of the 1,2-diarylfluoroethenes were much slower as compared to those of their unfluorinated analogues, and higher dilutions produced faster reactions. The method is straighforward, highly modular, and is applicable to the synthesis of fluoro PAHs and potentially to other fluoro PAHs that contain additionally substituted aryl moieties.

It has recently been reported that introduction of fluorine atom into phenacenes does not change their shape.16c However, in the present cases, we have observed that fluorine-atom substitution does elicit influence on the shapes of the molecules when compared to their unfluorinated analogues. A small deviation from planarity was observed for 6-F-Ch in comparison to chrysene, which is planar, and deviation from planarity increased in 5-F-Ch containing a bay-region fluorine atom. On the other hand, in comparison to BcPh, both 5- and 6-F-BcPh are slightly less nonplanar. Also, as reported by other investigators, we have observed positional disorder in the fluorine atom positions. Additionally, the molecular assemblies in the crystal structure are stabilized by π–π stacking interactions as well as through the formation of C–H···F intermolecular interactions. These features highlight the important role that fluorine substitution plays in organic molecules. Earlier studies by Thalladi et al.34 showed that, in general, C–H···F hydrogen bonds were preferred to F···F contacts. The marked difference in crystal packing behavior between fluorine and the heavier halogens is confirmed with our molecules. In more angularly fused BgCh series, a more dramatic shape change occurred, with the most pronounced effect in 9-F-BgCh. In this case, the fluorine atom resides in the bay region and causes substantial planarization of B, C, E rings forming the bay region, possibly via intramolecular F···H bonding.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

THF was distilled over LiAlH4 and then over sodium, toluene and benzene were distilled over sodium, and CH2Cl2 was distilled over CaCl2. DMF was obtained from commercial sources and was used without further purification. For reactions performed in a nitrogen atmosphere, glassware was dried with heat gun under vacuum. LDA (2.0 M solution in heptane/THF/EtPh) and LHMDS (1.0 M in THF) were obtained from commercial sources. All other reagents were obtained from commercial sources and were used as received. We have previously reported syntheses of 2-[fluoro(phenyl)methylsulfonyl]benzo[d]thiazole (2a),21 2-[fluoro(naphthalen-1-yl)methylsulfonyl]benzo[d]thiazole (2b),20b and of 2-[fluoro(naphthalen-2-yl)methylsulfonyl]benzo[d]thiazole (2c),21 and their precursor sulfones 1a,21 1b,20b and 1c.21 Photocyclizations of alkenes were performed in a Hanovia immersion-type photoreactor using a 450 W Hg vapor lamp and a quartz filter. Thin layer chromatography was performed on glass-backed silica gel plates (250 μm). Column chromatographic purifications were performed on 200–300 mesh silica gel. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 500 MHz and were referenced to residual protio solvent. 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 125 MHz and were referenced to the carbon resonance of the deuterated solvent. 19F NMR spectra were recorded at 282 MHz with CFCl3 as the internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million, and coupling constants (J) are in hertz (Hz). On the basis of 2D NMR data, some proton and carbon assignments were made for 5-fluorochrysene (4), 10-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene (7), and 9-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene (8). HRMS data were obtained using a FTICR-MS, the ionization modes are specified under each compound heading.

Synthesis of 2-{[Fluoro(phenanthren-9-yl)methyl]sulfonyl}benzo[d]thiazole 2d

2-[(Phenanthren-9-ylmethyl)thio]benzo[d]thiazole

To a solution of the sodium salt of 1,3-benzo-2-thiazole (1.324 g, 7.00 mmol, 1.25 molar equiv) in DMF (20 mL) was added a solution of 9-(bromomethyl)phenanthrene (1.518 g, 5.60 mmol) in DMF (30 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt and monitored by TLC (SiO2, 20% EtOAc in hexanes). After 6.0 h, complete consumption of 9-(bromomethyl)phenanthrene was observed, and the reaction was quenched with aq NH4Cl solution (30 mL). The mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x), the combined organic layers were washed aq NaHCO3 solution (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure, and crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 10% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure 2-[(phenanthren-9-ylmethyl)thio]benzo[d]thiazole (1.821 g, 91%) as a colorless solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.76 (br dd, J = 8.5, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.67 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (br dd, J = 8.3, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (s, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.72–7.64 (m, 3H), 7.59 (td, J = 7.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (td, J = 7.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (td, J = 7.8, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 5.18 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.7, 153.4, 135.6, 131.5, 131.1, 130.8, 130.5, 130.0, 129.4, 128.8, 127.3, 127.2, 127.1, 127.0, 126.3, 124.63, 124.55, 123.6, 122.8, 121.8, 121.3, 36.4. HRMS (ESI) [M+H]+ calcd. for C22H16NS2 358.0719, found 358.0723.

2-[(Phenanthren-9-ylmethyl)sulfonyl]benzo[d]thiazole 1d

A solution of 2-[(phenanthren-9-ylmethyl)thio]benzo[d]thiazole (0.943 g, 2.64 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of mCPBA (1.365 g, 7.91 mmol, 3.00 molar equiv) in CH2Cl2 (30 mL), cooled to 0 °C. After complete addition, the mixture was stirred at rt overnight. The reaction was quenched with aq NaHCO3 (30 mL), the organic layer was separated and washed with aq NaHCO3 (30 mL), 5% aq NaOH (30 mL, twice), water and then brine (30 mL each), and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 30% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure 2-[(phenanthren-9-ylmethyl)sulfonyl]benzo[d]thiazole (1d) as a colorless solid (0.728 g, 71%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.68 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.51 (m, 3H), 5.32 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.6, 152.8, 137.4, 133.0, 131.05, 130.98, 130.92, 130.5, 129.0, 128.2, 128.0, 127.8, 127.14, 127.12, 127.0, 125.6, 124.6, 123.3, 122.7, 122.4, 121.6, 58.7. HRMS (ESI) [M+H]+ calcd. for C22H16NO2S2 390.0617, found 390.0622.

2-{[Fluoro(phenanthren-9-yl)methyl]sulfonyl}benzo[d]thiazole 2d

A stirring solution of sulfone 1d (0.488 g, 1.25 mmol) in dry toluene (80 mL) was cooled under nitrogen gas to −78 °C (dry ice/iPrOH). LDA (0.800 mL, 1.60 mmol, 1.28 molar equiv) was added, and after 12 min, solid NFSI (0.488 g, 1.55 mmol, 1.24 molar equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at −78 °C for 50 min, then warmed to rt, and stirring was continued for an additional 50 min. Saturated aq NH4Cl was added to the reaction mixture, and the layers were separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3x), and the combined organic layer was washed with saturated aq NaHCO3 (30 mL) and brine (30 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 20% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure 2-{[fluoro(phenanthren-9-yl)methyl]sulfonyl}benzo[d]thiazole 2d as a white solid (0.357 g, 70%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.76–8.73 (m, 1H), 8.68 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.34–8.32 (m, 2H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.76–7.60 (m, 6H), 7.54 (d, J = 45.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.5, 153.1, 137.7, 131.8, three resonances at 131.0, 130.9, 130.8 (2C, one s and one d), 130.4, 129.9, 129.1 (d, J = 6.5 Hz), 128.9, 128.6, 128.0, 127.6, 127.4 (2C), 125.9, 124.3, 123.5, 122.8, 122.5, 121.3 (d, J = 17.3 Hz), 99.8 (d, J = 221.9 Hz). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −171.5 (d, J = 42.7 Hz). HRMS (ESI) [M+Na]+ calcd. for C22H14FNO2S2Na 430.0342, found 430.0339.

Synthesis of 6-Fluorochrysene 312a,16c,17,35

Step 1. Condensation of 2a with 1-naphthaldehyde

A solution of 1-naphthaldehyde (0.491 g, 3.14 mmol) and sulfone 2a (1.161 g, 3.59 mmol, 1.14 molar equiv) in dry THF (60 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. LHMDS (7.60 mL, 7.60 mmol, 2.42 molar equiv) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min, allowed to warm to rt and stirred at rt. After 1 h, TLC (10% EtOAc in hexanes) showed complete disappearance of the aldehyde. Saturated aq NH4Cl (30 mL) was added and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with NaHCO3 (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, eluted with hexanes, followed by 2% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure (E/Z)-1-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.8:1) as a colorless liquid (0.773 g, 99%). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ–100.0 (d, J = 21.4 Hz, 1F), −115.6 (d, J = 39.7 Hz, 1F). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C18H13F 248.0996, found 248.0997.

Step 2. Photocyclization of (E/Z)-1-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene to 3.12a,16c,17,35

(E/Z)-1-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.8:1, 63.1 mg, 0.254 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (250 mL), I2 (71.1 mg, 0.280 mmol, 1.10 molar equiv) was added, and nitrogen was bubbled into the solution for 10 min. Propylene oxide (2.90 mL, 2.41 g, 41.4 mmol, 163 molar equiv) was added, the solution was subjected to irradiation, and the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR. After 8 h, 19F NMR showed consumption of the (E/Z)-alkene. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 2% EtOAc in hexanes) to afford pure 6-fluorochrysene 3 (45.1 mg, 72%) as a white solid. For X-ray analysis, this compound was crystallized from hexanes/2–3 drops of CH2Cl2. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.1 (d, J = 250.8 Hz), 132.6, 132.2 (d, J = 5.8 Hz), 130.4 (d, J = 4.4 Hz), 128.9 (one resonance of the doublet partially buried under a singlet), 128.8, 127.9, 127.0, 126.9, 126.7 (d, J = 2.2 Hz), 125.5, 123.9 (d, J = 17.8 Hz), 123.5 (d, J = 3.2 Hz), 123.4, 121.4 (d, J = 5.9 Hz), 121.1, 104.1 (d, J = 22.0 Hz). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −123.8 (d, J = 15.3 Hz).

Synthesis of 5-Fluorochrysene 416c,17

Step 1. Condensation of 2b with benzaldehyde

A solution of benzaldehyde (38.8 mg, 0.366 mmol) and sulfone 2b (147 mg, 0.411 mmol, 1.12 molar equiv) in dry THF (20 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. LHMDS (0.980 mL, 0.980 mmol, 2.68 molar equiv) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min, allowed to warm to rt and stirred at rt. After 1 h, TLC (5% EtOAc in hexanes) showed complete disappearance of the aldehyde. Saturated aq NH4Cl (30 mL) was added and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with NaHCO3 (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, eluted with 5% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure (E/Z)-1-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.9:1, 73.5 mg, 81%). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −84.4 (d, J = 18.3 Hz, 1F), −95.2 (d, J = 39.7 Hz, 1F). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C18H13F 248.0996, found 248.1000.

Step 2. Photocyclization of (E/Z)-1-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene to 4.16c,17

(E/Z)-1-(1-Fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.9:1, 70.0 mg, 0.282 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (250 mL), I2 (78.3 mg, 0.308 mmol, 1.10 molar equiv) was added, and nitrogen was bubbled into the solution for 10 min. Propylene oxide (3.20 mL, 2.66 g, 45.8 mmol, 162 molar equiv) was added, the solution was subjected to irradiation, and the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR. After 16 h, 19F NMR showed consumption of the alkene. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 2% CH2Cl2 in hexanes) to yield pure 5-fluorochrysene 4 as a white solid (49.2 mg, 71%). For X-ray analysis, this compound was crystallized from hexanes/2–3 drops of CH2Cl2. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ9.25 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.8 Hz, 1H, H-4), 8.75 (dd, J = 7.8, 0.9 Hz, 1H, H-10), 8.73 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.3 Hz, 1H, H-11), 8.06 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, H-12), 8.02 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H-1), 7.93–7.91 (m, 1H, H-7), 7.73 (br t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H-3), 7.68 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.69–7.64 (m, 3H, H-2, H-8, H-9). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 160.0 (d, J = 252.7 Hz, C-5), 132.9, 132.3 (d, J = 11.4 Hz), 131.5 (d, J = 5.5 Hz), 129.2 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, C-12), 129.1 (d, J = 5.5 Hz), 128.7 (C-1), 128.04 (d, J = 1.1 Hz), 128.0 (d, J = 26.6 Hz, C-4), 127.7 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, C-7), 127. 5 (d, J = 3.2 Hz), 127.4, 126.9 (d, J = 2.3 Hz), 126.0 (d, J = 2.3 Hz), 123.6 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, C-10), 121.2 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, C-11), 120.1 (d, J = 11.9 Hz), 111.1 (d, J = 24.7 Hz, C-6). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3, resolution enhanced): δ −111.8 (br dt, J = 15.7, 3.3 Hz).

Synthesis of 5-Fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene 511a,15a

Step 1. Condensation of 2a with 2-naphthaldehyde

A solution of 2-naphthaldehyde (393 mg, 2.51 mmol) and sulfone 2a (880 mg, 2.86 mmol, 1.10 molar equiv) in dry THF (25.0 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. LHMDS (6.50 mL, 6.50 mmol, 2.40 molar equiv) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min, allowed to warm to rt and stirred at rt. After 2 h, TLC (10% EtOAc in hexanes) showed complete disappearance of the aldehyde. Saturated aq NH4Cl (30 mL) was added and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with NaHCO3 (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, eluted with hexanes, followed by 2% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure (E/Z)-2-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene21 (E:Z ratio 2.9:1) as a yellowish solid (581 mg, 99%). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −96.2 (d, J = 18.3 Hz, 1F), −114.4 (d, J = 39.7 Hz, 1F). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C18H13F 248.0996, found 248.0995.

Step 2. Photocyclization of (E/Z)-2-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene to 5.11a,15a

(E/Z)-2-(2-Fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.9:1, 60.0 mg, 0.241 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (250 mL), I2 (64.4 mg, 0.253 mmol, 1.05 molar equiv) was added, and nitrogen was bubbled into the solution for 10 min. Propylene oxide (2.80 mL, 2.32 g, 40.0 mmol, 166 molar equiv) was added, the solution was subjected to irradiation, and the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR. After 12 h, 19F NMR showed consumption of (E/Z)-2-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 2% CH2Cl2 in hexanes) to yield pure 5-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene 5 as a white solid (39.1 mg, 66%). For X-ray analysis, this compound was crystallized from hexanes/2–3 drops of CH2Cl2. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.16 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 9.07 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.68 (m, 4H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 157.4 (d, J = 252.7 Hz), 133.2, 132.0 (d, J = 5.0 Hz), 131.2 (d, J = 9.2 Hz), 130.4, 128.9, 128.4, 128.1 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 127.7, 127.3, 126.7, 126.5 (d, J = 3.7 Hz), 126.4 (d, J = 1.4 Hz), 125.9, 124.9 (d, J = 17.4 Hz), 124.6 (d, J = 2.3 Hz), 121.3 (d, J = 6.4 Hz), 108.9 (d, J = 20.1 Hz). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −125.4 (d, J = 9.2 Hz).

Synthesis of 6-Fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene 611a,15a,17

Step 1. Condensation of 2c with benzaldehyde

A solution of benzaldehyde (228 mg, 2.15 mmol) and sulfone 2c (920 mg, 2.58 mmol, 1.20 molar equiv) in dry THF (28 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. LHMDS (5.15 mL, 5.15 mmol, 2.40 molar equiv) was added dropwise at 0 °C and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C. After 2 h, TLC (10% EtOAc in hexanes) showed complete disappearance of the aldehyde. Saturated aq NH4Cl (30 mL) was added and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with NaHCO3 (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, eluted with 5% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure (E/Z)-2-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.75:1) as an off-white solid (460 mg, 76%). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −96.6 (d, J = 21.4 Hz, 1F) and −114.9 (d, J = 39.7 Hz, 1F). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C18H13F 248.0996, found 248.0999.

Step 2. Photocyclization of (E/Z)-2-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene to 6.11a,15a,17

(E/Z)-2-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene (E:Z ratio 2.75:1, 127 mg, 0.512 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (250 mL), I2 (144 mg, 0.567 mmol, 1.11 molar equiv) was added, and nitrogen was bubbled into the solution for 10 min. Propylene oxide (7.17 mL, 5.95 g, 102 mmol, 200 molar equiv) was added, the solution was subjected to irradiation, and the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR. After 26 h, 19F NMR showed consumption of the alkene. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 2.5% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene 6 as a white solid (105 mg, 83%). For X-ray analysis, this compound was crystallized from hexanes/2–3 drops of CH2Cl2, m.p. 72–73 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.12 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 9.10 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.99–7.95 (m, 2H), 7.73–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.63 (t, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 157.2 (d, J = 251.3 Hz), 133.9, 133.3 (d, J = 10.6 Hz), 130.1 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 129.5 (d, J = 4.8 Hz), 129.0, 128.3 (one resonance of the doublet partially buried under a singlet), 128.24, 128.22, 128.19, 128.0, 126.78, 126.77, 126.73, 125.5 (d, J = 1.9 Hz), 123.0 (d, J = 18.2 Hz), 118.7 (d, J = 8.6 Hz), 109.1 (d, J = 20.1 Hz). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −125.8 (d, J = 12.2 Hz).

Synthesis of 10-Fluorobenzo[g]chrysene 7

Step 1. Condensation of 2a with phenanthrene-9-carboxaldehyde

A solution of phenanthrene-9-carboxaldehyde (79.7 mg, 0.386 mmol) and sulfone 2a (149 mg, 0.459 mmol, 1.19 molar equiv) in dry THF (10 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. LHMDS (0.90 mL, 0.90 mmol, 2.33 molar equiv) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min, allowed to warm to rt and stirred at rt. After 1 h, TLC (5% EtOAc in hexanes) showed complete disappearance of the aldehyde. Saturated aq NH4Cl (30 mL) was added and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with NaHCO3 (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, eluted with 5% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure (E/Z)-9-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene (E:Z ratio 3.1:1) as a colorless liquid (80.7 mg, 70%). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −100.3 (d, J = 21.4 Hz, 1F), −115.2 (d, J = 36.6 Hz, 1F). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C22H15F 298.1152, found 298.1159.

Step 2. Photocyclization of (E/Z)-9-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene to 7

(E/Z)-9-(2-Fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene (E:Z ratio 3.1:1, 80.7 mg, 0.270 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (250 mL), I2 (84.1 mg, 0.331 mmol, 1.23 molar equiv) was added, and nitrogen was bubbled into the solution for 10 min. Propylene oxide (3.12 mL, 2.59 g, 44.6 mmol, 165 molar equiv) was added, the solution was subjected to irradiation, and the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR. After 8.5 h, 19F NMR showed consumption of (E/Z)-9-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 4% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure 10-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene 7 as a white solid (61.3 mg, 77%). For X-ray analysis, this compound was crystallized from hexanes/2–3 drops of CH2Cl2, m.p. 141 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.95 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 8.81 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.71–8.68 (m, 1H), 8.50–8.48 (m, 1H), 8.31–8.29 (m, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H, H-9), 7.72–7.62 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.3 (d, J = 251.7 Hz, C-10), 131.9 (d, J = 5.0 Hz), 130.7, 130.4, 129.5 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 129.4, 129.2, 128.7 (d, J = 2.7 Hz), 127.8, 127.6, 127.2, 126.7, 126.5, 126.4, 124.6 (d, J = 17.4 Hz), 124.3 (d, J = 2.6 Hz), 124.0, 123.7, 123.4, 121.0 (d, J = 5.5 Hz), 104.1 (d, J = 21.5 Hz, C-9). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −124.3 (d, J = 12.2 Hz). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C22H13F 296.0996, found 296.0998.

Synthesis of 9-Fluorobenzo[g]chrysene 8

Step 1. Condensation of 2d with benzaldehyde

A solution of benzaldehyde (59.7 mg, 0.563 mmol) and sulfone 2d (270 mg, 0.664 mmol, 1.18 molar equiv) in dry THF (10 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. LHMDS (1.40 mL, 1.40 mmol, 2.49 molar equiv) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min, allowed to warm to rt and stirred at rt. After 1 h, TLC (10% EtOAc in hexanes) showed complete disappearance of the aldehyde. Saturated aq NH4Cl (30 mL) was added and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with NaHCO3 (30 mL), brine (30 mL), and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, eluted with 5% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure (E/Z)-9-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene (E:Z ratio 2.88:1) as a colorless liquid (149 mg, 89%). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −85.0 (d, J = 21.4 Hz, 1F), −95.3 (d, J = 36.6 Hz, 1F). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C22H15F 298.1152, found 298.1151.

Step 2. Photocyclization of (E/Z)-9-(1-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene to 8

(E/Z)-9-(1-Fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)phenanthrene (E:Z ratio 2.88:1, 76.1 mg, 0.255 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (250 mL), I2 (71.3 mg, 0.281 mmol, 1.10 molar equiv) was was added, and nitrogen was bubbled into the solution for 10 min. Propylene oxide (2.80 mL, 2.32 g, 40.0 mmol, 157 molar equiv) was added, the solution was subjected to irradiation, and the reaction was monitored by 19F NMR. After 8 h, 19F NMR showed consumption of the alkene. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 2% EtOAc in hexanes) to yield pure 9-fluorobenzo[g]chrysene 8 as a white solid (55.1 mg, 73%). For X-ray analysis, this compound was crystallized from EtOH/2–3 drops of benzene/1 drop of CH2Cl2. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.07 (dt, J = 8.1, 2.2 Hz, 1H, H-8), 8.82 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.71 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, H-11), 7.75–7.70 (m, 3H), 7.67 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, H-10), 7.65–7.55 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.3 (d, J = 251.7 Hz, C-9), 133.2 (d, J = 11.0 Hz), 131.5, 131.3 (d, J = 4.1 Hz), 130.4, 130.1, 129.2 (d, J = 2.4 Hz), 129.0, 128.0 (d, J = 26.1 Hz, C-8), 127.8, 127.7, 127.6, 127.4, 127.2 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, C-11), 126.9, 126.4, 125.2, 123.8, 123.1, 119.9 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, C-10a), 111.3 (d, J = 24.7 Hz, C-10). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3, resolution enhanced): δ −114.6 ppm (dd, J = 15.1; 2.3 Hz). HRMS (+APPI mode) [M]+ calcd. for C22H13F 296.0996, found 296.1002.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant CHE-1058618, partially by NIH (NIGMS) Grant S06 GM008168, and by PSC CUNY awards. Infrastructural support was provided by National Institutes of Health Grant 8G12MD007603 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. We thank Dr. Andrew Poss (Honeywell) for a sample of NFSI, and Dr. Sakilam Satishkumar for his assistance with obtaining some NMR spectra. We thank Ms. Wei Wei, Ms. Marikone Gaši, and Mr. Michael Benavidez for resynthesis of 1-styrylnaphthalene and (E/Z)-1-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene for the UV measurements, and Ms. Karen Lo for obtaining the UV spectra of these alkenes. We thank Mr. Satish Lakshman (Pixiedust) for the final design of the cover art and Professor Mahesh Lakshman (CCNY) for his help and advice with the musical aspects represented in the cover art.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra, 2D NMR spectra for compounds 4, 7, and 8, UV spectra of 1-styrylnaphthalene and (E/Z)-1-(2-fluoro-2-phenylvinyl)naphthalene, details of the X-ray crystallographic analysis, ORTEP figures and CIF files for compounds 3, 5–8, chrysene, and benzo[g]chrysene.

Contributor Information

Miriam Rossi, Email: rossi@vassar.edu.

Barbara Zajc, Email: bzajc@ccny.cuny.edu.

References

- 1.(a) Kirsch P. Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry. Synthesis, Reactivity, Applications. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2004. [Google Scholar]; (b) Okazaki T, Laali KK. Fluorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (hetero-PAHs); synthesis and utility. In: Laali KK, editor. Modern Organofluorine Chemistry–Synthetic Aspects. Vol. 2. Bentham Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 353–380. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kirsch P, Bremer M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2000;39:4216–4235. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001201)39:23<4216::AID-ANIE4216>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Babudri F, Farinola GM, Naso F, Ragni R. Chem Commun. 2007:1003–1022. doi: 10.1039/b611336b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Berger R, Resnati G, Metrangolo P, Weber E, Hulliger J. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:3496–3508. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00221f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xu T, Yu L. Mater Today. 2014;17:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Andersson JT, Weis U. J Chromatogr A. 1994;659:151–161. [Google Scholar]; (b) Luthe G, Ramos L, Dallüge J, Brinkman UATh. Chromatographia. 2003;57:379–383. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey RG. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Chemistry and Carcinogenicity; Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerina DM, Sayer JM, Agarwal SK, Yagi H, Levin W, Wood AW, Conney AH, Pruess-Schwartz D, Baird WM, Pigott MA, Dipple A. Reactivity and tumorigenicity of bay-region diol epoxides derived from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Kocsis JJ, Jollow DJ, Witmer CM, Nelson JO, Snyder R, editors. Biological Reactive Intermediates III. Plenum Press; New York: 1986. pp. 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Jerina DM, Chadha A, Cheh AM, Schurdak ME, Wood AW, Sayer JM. Covalent bonding of bay-region diol epoxides to nucleic acids. In: Witmer CM, Snyder R, Jollow DJ, Kalf GF, Kocsis JJ, Sipes IG, editors. Biological Reactive Intermediates IV. Plenum Press; New York: 1991. pp. 533–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dipple A. Reactions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with DNA. In: Hemminki K, Dipple A, Shuker DEG, Kadlubar FF, Sagerbäck D, Bartsch H, editors. DNA Adducts: Identification and Biological Significance. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 1994. pp. 107–129. Scientific Publication No. 125. [Google Scholar]; (c) Szeliga J, Dipple A. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:1–11. doi: 10.1021/tx970142f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Penning TM, Burczynski ME, Hung CF, McCoull KD, Palackal NT, Tsuruda LS. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:1–18. doi: 10.1021/tx980143n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bolton JL, Trush MA, Penning TM, Dryhurst G, Monks TJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Jerina DM, Sayer JM, Yagi H, Croisy-Delcey M, Ittah Y, Thakker DR, Wood AW, Chang RL, Levin W, Conney AH. Highly tumorigenic bay-region diol epoxides from the weak carcinogen benzo[c]phenanthrene. In: Snyder R, Parke DV, Kocsis JJ, Jollow DJ, Gibson CG, Witmer CM, editors. Biological Reactive Intermediates II Part A. Plenum Press; New York: 1982. pp. 501–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Prasad GKB, Mirsadeghi S, Boehlert C, Byrd RA, Thakker DR. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3676–3683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Buhler DR, Unlu F, Thakker DR, Slaga TJ, Conney AH, Wood AW, Chang RL, Levin W, Jerina DM. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1541–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chang RL, Wood AW, Conney AH, Yagi H, Sayer JM, Thakker DR, Jerina DM, Levin W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8633–8636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cavalieri E, Rogan E, Higginbotham S, Cremonesi P, Salmasi S. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:10–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00390479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cavalieri E, Rogan E, Higginbotham S, Cremonesi P, Salmasi S. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:16–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00390480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bae S, Mah H, Chaturvedi S, Musafia TJ, Baird WM, Katz AK, Carrell HL, Glusker JP, Okazaki T, Laali KK, Zajc B, Lakshman MK. J Org Chem. 2007;72:7625–7633. doi: 10.1021/jo071145s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Mirsadeghi S, Prasad GKB, Whittaker N, Thakker DR. J Org Chem. 1989;54:3091–3096. [Google Scholar]; (b) Laali KK, Hansen PE. J Org Chem. 1993;58:4096–4104. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fakuhara T, Sekiguchi M, Yoneda N. Chem Lett. 1994:1011–1012. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang T, Huang Y, Cho BP. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:242–254. doi: 10.1021/tx050308+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Laali KK, Tanaka M, Forohar F, Cheng M, Fetzer JC. J Fluorine Chem. 1998;91:185–190. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zajc B. Application of xenon difluoride in synthesis. In: Laali K, editor. Modern Organofluorine Chemistry–Synthetic Aspects. Vol. 2. Bentham Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 61–157. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zajc B. J Org Chem. 1999;64:1902–1907. doi: 10.1021/jo9819178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Girke W, Bergmann ED. Chem Ber. 1976;109:1038–1045. [Google Scholar]; (b) Harvey RG, Cortez C. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:7101–7118. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Marx GS, Bergmann ED. J Org Chem. 1972;37:1807–1810. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ittah Y, Jerina DM. J Fluorine Chem. 1980;16:137–144. [Google Scholar]; (c) Weis U, Andersson JT. Polycycl Aromat Comp. 2002;22:71–85. [Google Scholar]; (d) Li H, He KH, Liu J, Wang BQ, Zhao KQ, Hu P, Shi ZJ. Chem Commun. 2012;48:7028–7030. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Li Z, Twieg RJ. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:15534–15539. doi: 10.1002/chem.201502473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Furuya T, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10060–10061. doi: 10.1021/ja803187x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee HG, Milner PJ, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3792–3795. doi: 10.1021/ja5009739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fuchibe K, Morikawa T, Shigeno K, Fujita T, Ichikawa J. Org Lett. 2015;17:1126–1129. doi: 10.1021/ol503759d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Synthesis of several F-PAHs, including 9-fluorophenanthrene, 5- and 6-fluorochrysene, 6-fluorobenzo[c]phenanthrene, and 5-fluorobenzo[k]chrysene: Fuchibe K, Mayumi Y, Zhao N, Watanabe S, Yokota M, Ichikawa J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:7825–7828. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302740.

- 18.(a) Blakemore PR. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 2002:2563–2585. [Google Scholar]; (b) Plesniak K, Zarecki A, Wicha J. Top Curr Chem. 2007;275:163–250. doi: 10.1007/128_049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Aïssa C. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:1831–1844. [Google Scholar]

- 19.For reviews on fluoroolefination using the Julia-Kocienski approach, see: Zajc B, Kumar R. Synthesis. 2010:1822–1836. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1218789.Pfund E, Lequeux T, Gueyrard D. Synthesis. 2015;47:1534–1546.

- 20.For our recent efforts in this area, see: Kumar R, Pradhan P, Zajc B. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3891–3893. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05083k.Mandal SK, Ghosh AK, Kumar R, Zajc B. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:3164–3167. doi: 10.1039/c2ob07031f.Kumar R, Zajc B. J Org Chem. 2012;77:8417–8427. doi: 10.1021/jo300971w.Chowdhury M, Mandal SK, Banerjee S, Zajc B. Molecules. 2014;19:4418–4432. doi: 10.3390/molecules19044418.Kumar R, Singh G, Todaro LJ, Yang L, Zajc B. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:1536–1549. doi: 10.1039/c4ob02179g.

- 21.Ghosh AK, Zajc B. Org Lett. 2006;8:1553–1556. doi: 10.1021/ol060002+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Laarhoven WH. Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1983;102:185–204. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mallory FB, Mallory CW. Org Reactions. 1984;30:1–456. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jørgensen KB. Molecules. 2010;15:4334–4358. doi: 10.3390/molecules15064334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Yang B, Katz TJ, Poindexter MK. J Org Chem. 1991;56:3769–3775. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alacid E, Nájera C. Adv Synth Cat. 2006;348:2085–2091. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackner B, Bretterbauer K, Schwarzinger C, Falk H. Monatsh Chem. 2005;136:2067–2082. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nayak SK, Reddy MK, Chopra D, Row TNG. CrystEngComm. 2012;14:200–210. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Champagne PA, Desroches J, Paquin JF. Synthesis. 2015;47:306–322. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arunan E, Desiraju GR, Klein RA, Sadlej J, Scheiner S, Alkorta I, Clary DC, Crabtree RH, Dannenberg JJ, Hobza P, Kjaergaard HG, Legon AC, Mennucci B, Nesbitt DJ. Pure Appl Chem. 2011;83:1619–1636. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laali KK, Okazaki T. J Org Chem. 2001;66:780–788. doi: 10.1021/jo001268b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutnaes BF, Luthe G, Brinkman UATh, Johansen JE, Krane J. Magn Reson Chem. 2005;43:588–594. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1584. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.See for example: Mallory FB, Mallory CW. Coupling through space in organic chemistry. In: Grant DM, Harris RK, editors. Encyclopedia of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Vol. 3. J. Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 1996. pp. 1491–1501. Online 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.Hierso JC. Chem Rev. 2014;114:4838–4867. doi: 10.1021/cr400330g.

- 32.Mallory FB, Mallory CW, Ricker WM. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:4770–4771. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sardella DJ, Boger E. Magn Res Chem. 1989;27:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thalladi VR, Weiss HC, Bläser D, Boese R, Nangia A, Desiraju GR. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8702–8710. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laali KK, Hollenstein S, Harvey RG, Hansen PE. J Org Chem. 1997;62:4023–4028. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.