Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to develop an assessment tool for activities of daily living (ADL) from the perspective of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and examine the validity and reliability of the assessment.

Methods

A preliminary 45-item questionnaire was developed through intensive interviews with 54 patients with PD and administered to another group of 248 patients with PD. Based on clinical and statistical analyses, 20 ADL-items were selected. The final 20-item questionnaire was examined in the other group of 59 patients with PD.

Results

The new ADL questionnaire showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α, 0.962–0.966) and acceptable test-retest reliability (0.632–0.984). Concurrent validity was shown as a significant positive correlation between the new ADL questionnaire and other ADL or clinical instruments. The Hoehn and Yahr stage showed the highest degree of correlation with the new ADL questionnaire, followed by the other ADL scales (Schwab and England ADL and the ADL subscore of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale). Additionally, a regression analysis was conducted with the disease-specific quality of life questionnaire, and the new ADL questionnaire was the most powerful predictor of quality of life among the clinical instruments.

Conclusions

The new ADL questionnaire is a valid tool for assessing ADL from the perspectives of patients with PD.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Activities of daily living, Questionnaire

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic disorder due to the progressive degeneration of dopamine-producing cells in brain structures, including the substantia nigra [1]. PD is characterized by motor disturbances, such as tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. Clinical presentations of PD also include a variety of non-motor symptoms. Thus, patients with PD are vulnerable to decreased activities of daily living (ADL), such as walking, talking, swallowing, or simple tasks like bathing or dressing [2].

Despite the recent development of medical, surgical, and rehabilitative treatments, PD remains a progressive condition; there are no proven management strategies to reverse or halt its pathological processes. Patients with PD are at increased risk for decreased activities of daily living (ADL) with progression of the disease, particularly those requiring coordination and balance [3–5]. The treatment goal for patients with PD is to focus on symptoms and improve ADL. Therefore, it is mandatory to assess the ADL of patients with PD, which is essential for evaluating the effectiveness of symptomatic and potentially disease-modifying treatments.

Some studies have focused on the ADL of patients with PD. However, these studies have revealed limitations due to a lack of reliable and valid tools for assessing ADL from the patient’s perspective [6–10]. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) is widely used to assess mentation, ADL, motor symptoms, and treatment complications in patients with PD [11]. The advantages of the ADL subsection of the UPDRS have been well described [12, 13]. However, it has been criticized due to its ambiguity and redundancy of items, such as items overlapping in the ADL and motor sections, and a lack of the patient’s perspective has also been reported [11, 14]. It also requires an interview by an examiner. The new version of the UPDRS includes motor experiences associated with ADL that are self-evaluated by patients or their caregivers [14]. However, the new version does not differ greatly from the old version and fails to evaluate ADL comprehensively.

Improvements in motor symptoms, which are unresponsive to medical and surgical treatments, have been observed in patients with PD with recent advancements in rehabilitation therapy [15]. These symptoms are related to balance, walking, and mobility, all of which constitute the ADL of patients with PD. However, the UPDRS shows limited validity for assessing the effects of physiotherapy on balance and mobility, both of which are essential when measuring the ADL of patients with PD [16].

We developed a new ADL questionnaire from the patient’s perspective and assessed its validity and reliability in this cross-sectional study.

Methods

Study patients

Patients with PD were recruited consecutively from an outpatient clinic in a specialized center of a referral hospital. Patients were diagnosed with clinically probable PD according to the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria [17]. Patients with cognitive impairment based on a Korean Mini-Mental Status Examination (K-MMSE) score < 24 and patients without sufficient cognitive or physical ability to cooperate were excluded [18]. Patients who had other medical problems that seriously affected ADL, such as stroke, osteoarthritis, and angina, were also excluded.

Development of the preliminary 45-item questionnaire

Movement disorder and neurorehabilitation specialists reviewed motor aspects of disabilities of daily living in patients with PD with reference to various ADL scales and collected ADL items [19–25]. An open and intensive interview was performed with 54 patients with PD; they were asked whether they had disability in a collection of ADL items and were asked to add any other ADL items experienced during their daily lives. The preliminary 45-item ADL questionnaire was prepared and included household, outdoor, and social activities (Appendix 1).

Selection of the final 20-item questionnaire

Another group of 248 patients with PD (90 men and 158 women; mean age, 67.9 ± 9.2 years; mean K-MMSE score, 26.2 ± 3.8 points; mean Hoehn and Yahr [HY] stage, 2.4 ± 0.6) were asked to select the items that they found difficult in their daily living and were asked to select the three items that were most important to them using the preliminary 45-item questionnaire.

Clinical and statistical analyses were performed to select the ADL items. The frequency of items reflecting patient’s experience and importance and clinical significance for infrequent items, such as swallowing, were included in the clinical analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood to estimate the factor structure matrix. The number of items was determined using parallel analysis and the scree test. We used the Promax (Kappa = 2) oblique rotation method to simplify the structure, and each item was selected and classified based on a factor loading > 0.4.

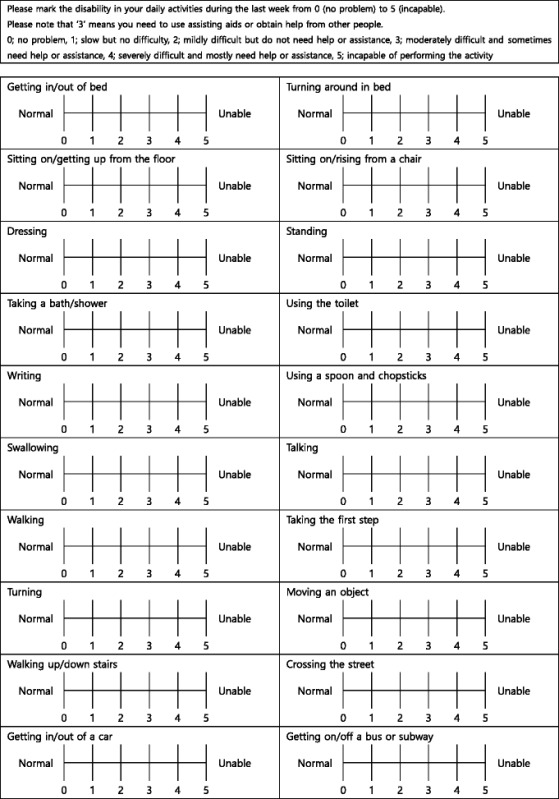

All items were given a score on a 5-point scale (0: no impairment of ADL and 5: inability to perform ADL) (Appendix 2).

Validation of the final 20-item questionnaire

Fifty-nine patients with mild-to-moderate PD were additionally recruited to validate the final 20-item questionnaire (Table 1). We assessed internal consistency of the new ADL questionnaire using Cronbach’s α. In addition, we performed repeated interviews at a 4-week interval to assess test-retest reliability. Concurrent validity was analyzed by the correlation between the new ADL questionnaire and other clinical instruments including the UPDRS, the Schwab and England ADL (SEADL) scale, Beck’s Depression Inventory [26], the Autonomic Dysfunction Questionnaire [27], the Fatigue Severity Scale [28], and the Parkinson’s disease quality of life (PDQL) questionnaire [29]. A simple regression analysis was conducted for the PDQL questionnaire to evaluate the influence of various clinical instruments on quality of life.

Table 1.

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the 59 patients who were evaluated to validate the 20-item questionnaire

| Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Number (male-to-female ratio) | 59 (22:37) |

| Age (years) | 66.85 ± 8.25 |

| Disease duration (years) | 6.14 ± 4.80 |

| Treatment duration (years) | 4.43 ± 4.00 |

| The daily dose of levodopa (mg/day) | 540.00 ± 296.21 |

| K-MMSE | 26.49 ± 2.85 |

| New questionnaire | 23.24 ± 22.29 |

| HY stage | 2.42 ± 0.58 |

| UPDRS | 45.78 ± 18.49 |

| Mentation | 3.26 ± 2.05 |

| ADL | 11.88 ± 6.22 |

| Motor | 27.91 ± 11.05 |

| Complications | 2.73 ± 2.97 |

| SEADL | 77.59 ± 15.89 |

| BDI | 22.38 ± 11.53 |

| PDQL | 115.53 ± 39.93 |

| Parkinson’s symptoms | 42.51 ± 14.14 |

| Systemic symptoms | 25.27 ± 9.64 |

| Social function | 19.21 ± 7.18 |

| Emotional function subscore | 28.54 ± 10.80 |

| ADQ | 19.21 ± 12.42 |

| FSS | 36.20 ± 15.69 |

K-MMSE Korean Mini-Mental Status Examination, HY Hoehn and Yahr, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, ADL Activities of Daily Living, SEADL Schwab and England ADL, BDI Beck’s Depression Inventory, PDQL Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life, ADQ Autonomic Dysfunction Questionnaire, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as proportions of patients (%) for categorical variable. The univariate analysis included Student’s t-test and Pearson’s chi-square test, as appropriate, to analyze differences between the two groups. A correlation analysis was conducted using Spearman’s method. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 19.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Evaluation of ADL with the preliminary 45-item questionnaire in 248 patients with PD

The most common ADL items experienced by patients were getting up (61.7 %), dressing (57.7 %), and moving objects (56.9 %) (Table 2). The most important ADL items selected by patients were “walking outside”, “using a spoon and chopsticks”, and “getting up”. Some differences in the frequencies for selected items were detected according to sex, such as “driving” for men, “preparing a meal”, “washing dishes”, “cleaning”, and “washing clothes” for women (chi-square test, P ≤ 0.05).

Table 2.

The most common disabilities during daily activities in patients with Parkinson’s disease using the preliminary 45-item questionnaire

| Items of ADL | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Getting up from the floor | 153 | 61.7 |

| Dressing | 143 | 57.7 |

| Moving objects | 141 | 56.9 |

| Wearing shoes | 136 | 54.8 |

| Writing | 134 | 54.0 |

| Walking inside | 133 | 53.6 |

| Walking outside | 131 | 52.8 |

| Standing | 130 | 52.4 |

| Turning around in bed | 126 | 50.8 |

| Sitting on the floor | 126 | 50.8 |

ADL Activities of Daily Living

A positive correlation was observed between the number of items patients found difficult and severity of the disease, as shown by the HY stage (Table 3).

Table 3.

The most common and important items in patients with Parkinson's disease according to Hoehn and Yahr stage using the preliminary 45 item questionnaire

| HY stage | Number of items | Most common items | Most important items |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.29 ± 1.60 | Getting up from the floor | Exercise |

| Sitting on the floor | Walking outside | ||

| Walking outside | Grasping and releasing objects | ||

| 2 | 11.31 ± 11.06 | Dressing | Walking outside |

| Getting up from the floor | Getting up from the floor | ||

| Writing | Using a spoon and chopsticks | ||

| 2.5 | 20.30 ± 12.04 | Getting up from the floor | Walking outside |

| Transferring objects | Sitting on the floor | ||

| Wearing shoes | Getting up from the floor | ||

| 3 | 24.18 ± 12.81 | Getting up from the floor | Walking outside |

| Moving objects | Taking the first step | ||

| Taking the first step | Getting in/out of bed | ||

| 4–5 | 34.50 ± 7.52 | Dressing | Waking outside |

| Getting in/out of a car | Using the toilet | ||

| Taking a bath/shower | Getting in/out of bed |

HY Hoehn and Yahr

Validation of the new ADL questionnaire in 59 patients with PD

The internal consistency of the new questionnaire was acceptable with an item-total correlation (range, 0.523–0.898) and high consistency, as shown by Cronbach’s α of 0.962–0.966. Test-retest reliability was acceptable, reached at 0.632–0.984. Concurrent validity was detected as significant correlations between scores on the new ADL questionnaire and other ADL scales (SEADL and the ADL subscore of the UPDRS). The other clinical instruments were also correlated with the new ADL questionnaire, except the MMSE (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations between the new questionnaire and other clinical instruments

| Coefficient | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| K-MMSE | −0.066 | 0.621 |

| HY stage | 0.682 | <0.001 |

| SEADL | −0.617 | <0.001 |

| UPDRS | 0.521 | <0.001 |

| Mentation’ | 0.313 | 0.021 |

| ADL’ | 0.608 | <0.001 |

| Motor’ | 0.322 | 0.018 |

| Complications’ | 0.562 | <0.001 |

| BDI | 0.586 | <0.001 |

| PDQL | −0.605 | <0.001 |

| Parkinson’s symptoms’ | −0.596 | <0.001 |

| Systemic symptoms’ | −0.527 | <0.001 |

| Social function’ | −0.589 | <0.001 |

| Emotional function’ | −0.594 | <0.001 |

| ADQ | 0.480 | 0.000 |

| FSS | 0.449 | 0.001 |

K-MMSE Korean Mini-Mental Status Examination, HY Hoehn and Yahr, SEADL Schwab and England ADL, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, ADL Activities of Daily Living, BDI Beck’s Depression Inventory, PDQL Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life, ADQ Autonomic Dysfunction Questionnaire, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale

The regression analysis for quality of life showed that the new ADL questionnaire was the most powerful predictor for quality of life in patients with PD followed by the ADL subscore of the UPDRS (Table 5). The new questionnaire and the ADL subscore of the UPDRS were the strongest predictors of the PDQL after adjusting for age, disease duration, treatment, and daily levodopa dosage (adjusted R2 values, 0.456 and 0.464, respectively).

Table 5.

Results of a simple regression analysis for the Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Score

| P-value | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| New questionnaire | <0.001 | 0.366 |

| K-MMSE | 0.746 | 0.002 |

| HY stage | 0.003 | 0.162 |

| SEADL | <0.001 | 0.280 |

| UPDRS | <0.001 | 0.232 |

| Mentation’ | 0.005 | 0.150 |

| ADL’ | <0.001 | 0.335 |

| Motor’ | 0.035 | 0.088 |

| Complications’ | <0.001 | 0.247 |

| BDI | 0.002 | 0.181 |

| ADQ | 0.011 | 0.128 |

| FSS | 0.238 | 0.030 |

K-MMSE Korean Mini-Mental Status Examination, HY Hoehn and Yahr, SEADL Schwab and England ADL, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, ADL Activities of Daily Living, BDI Beck’s Depression Inventory, ADQ Autonomic Dysfunction Questionnaire, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale

Discussion

The number of ADL items that were difficult for patients with PD increased according to the HY stage using the 45-item questionnaire, indicating that progression of the disease increased ADL impairment. This finding suggests that items on the preliminary questionnaire covered ADL throughout the disease stages and comprehensively reflected the patient’s perspectives.

Some differences were found in the list of selected items according to HY stage. However, the most common and important items for the patients were similar at all HY stages. Getting up was the most common, and walking outside was the most important activity. These findings suggest that mobility deserves special attention compared to others activities during the daily lives of these patients.

Among the most frequently selected 10 items, only four (dressing, writing, walking, and turning around in bed) are present in the ADL section of the UPDRS. These findings suggest that the ADL section of the UPDRS may be insufficient to reflect the daily disabilities of patients with PD.

The validity of the new questionnaire was acceptable, as shown by the correlation with other clinical measures. Concurrent validity was reasonable based on the high correlation of the new questionnaire with other ADL and clinical instruments, except the K-MMSE. Given that cognitive function can greatly affect ADL, this result may be distorted due to the limited distribution of the K-MMSE scores based on the exclusion criteria of this study. The new questionnaire showed the highest degree of correlation with HY stage and also had a high degree of correlation with other clinical instruments, such as the SEADL and the ADL section of the UPDRS. Moreover, the motor subscore of the UPDRS was marginally correlated with the new ADL questionnaire, but it was less correlated than depression, autonomic dysfunction, and fatigue. This finding is consistent with a recent report that severity of motor symptoms, as expressed by the motor subscore of the UPDRS, has less impact on the health status of patients with PD than non-motor symptoms [30].

Quality of life may be the most important clinical measure representing the current status of patients with PD. Our results show that the new questionnaire was a strong predictor of quality of life in patients with PD among the clinical instruments evaluated in this study. A regression analysis showed that the new questionnaire and the ADL subscore of the UPDRS had strong predictive value for quality of life in patients with PD after adjusting of for age, disease duration, treatment, and daily levodopa dosage.

Several limitations of this study should be discussed. Different importance could be assigned to some items in different cultures, such as “getting up from or sitting on the floor”. Thus, it may be necessary to validate the new questionnaire in different cultural areas. Also, there could be some biases from the predominance women in recruited patients at the evaluation of preliminary 45-item questionnaire. And, the new questionnaire showed relatively weak correlation with motor part of UDPRS, compared to other scales. This finding could suggest that the new questionnaire might not be sensitive enough as an assessment tool for motor changes responsive to physical therapy. Finally, this study was conducted using a cross-sectional design. Therefore, we failed to assess the feasibility of the new questionnaire for detecting changes along the course of the disease. This deserves further longitudinal studies.

Despite these limitations, the new questionnaire has several advantages over other clinical instruments; it reflects actual patient disabilities during daily living based on a patient’s perspective. Changes in the ADL of patients could be easily and effectively evaluated, because the questionnaire is designed for self-administration. Thus, the new questionnaire is applicable to long-term follow-up in an actual clinical setting.

Conclusion

The new questionnaire developed based on the perspective of patients with PD was found to be a valid tool for assessing ADLs of patients with PD.

Ethics and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dong-A University Hospital (No. 14–101) and patients submitted written informed consent.

Consent to publish

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting our findings is contained within the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Dong-A University Research Fund (S-M Cheon).

Abbreviations

- PDQL

Parkinson’s disease quality of life

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- HY

Hoehn and Yahr

- K-MMSE

Korean version of mini-mental status examination

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- SEADL

Schwab and England ADL scale

- UPDRS

Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale

Appendix

Appendix 1

Table 6.

Preliminary 45-item questionnaire

| Please check the daily activities that you find difficult to do during last week. Please list the three activities that are most important to you. | |

|---|---|

| Household | Outdoor |

| Getting in/out of bed | Taking the first step |

| Turning around in bed | Walking outside |

| Sitting on the floor | Turning |

| Getting up from the floor | Stopping walking |

| Dressing | Walking up/down stairs |

| Sex life | Crossing the street |

| Running | |

| Sitting on and rising from a chair | Getting in/out of a car |

| Sitting upright | Getting on/off of a bus or subway |

| Standing | Driving a car |

| Walking inside | |

| Grasping and releasing an object | If you (or the patient) cannot walk |

| Moving an object | Moving from the bed or a chair to a wheelchair |

| Writing | Using a wheelchair |

| Wearing shoes | |

| Social | |

| Brushing teeth | Talking |

| Getting in/out of the bath | Using the phone |

| Taking a bath/shower | Shopping |

| Using the toilet | Going out |

| Walking around the neighborhood | |

| Preparing a meal | Working |

| Using a spoon and chopsticks | Taking exercise |

| Swallowing | Doing hobbies |

| Washing the dishes | Traveling |

| Cleaning the house | |

| Washing the clothes | Activities most important for you. |

| 1. | |

| If you find any other activities difficult that are not in this list, please list them below. | 2. |

| 3. | |

Appendix 2

Table 7.

The new activities of daily living questionnaire

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

S-Y Lee and S-M Cheon participated in the design of the study, interpretation and analysis of data, and drafting the manuscript. SK Kim participated in the design of the study, developing the questionnaire, and drafting the manuscript. J-W Seo performed the statistical analysis. MA Kim helped developing the questionnaire. JW Kim participated in the design of the study and revising the manuscript. All authors have read and approve of the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Parkinson J. An essay on the shaking palsy. 1817. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14(2):223–236. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankovic J. Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(4):368–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. How does Parkinson's disease affect quality of life? A comparison with quality of life in the general population. Mov Disord. 2000;15(6):1112–1118. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200011)15:6<1112::AID-MDS1008>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shulman LM, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE, Vaughan CG, Reich SG, Fishman PS, et al. The evolution of disability in Parkinson disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(6):790–796. doi: 10.1002/mds.21879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jankovic J, Kapadia AS. Functional decline in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(10):1611–1615. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobson JP, Edwards NI, Meara RJ. The Parkinson's Disease Activities of Daily Living Scale: a new simple and brief subjective measure of disability in Parkinson's disease. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(3):241–246. doi: 10.1191/026921501666767060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keus S, Nieuwboer A, Bloem B, Borm G, Munneke M. Clinimetric analyses of the modified Parkinson activity scale. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(4):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hariz G, Forsgren L. Activities of daily living and quality of life in persons with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease according to subtype of disease, and in comparison to healthy controls. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;123(1):20–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morley D, Selai C, Thompson A. The self-report Barthel Index: preliminary validation in people with Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(6):927–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramaker C, Marinus J, Stiggelbout AM, van Hilten BJ. Systematic evaluation of rating scales for impairment and disability in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(5):867–876. doi: 10.1002/mds.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson's Disease The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003;18(7):738–750. doi: 10.1002/mds.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrag A, Spottke A, Quinn NP, Dodel R. Comparative responsiveness of Parkinson's disease scales to change over time. Mov Disord. 2009;24(6):813–818. doi: 10.1002/mds.22438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison MB, Wylie SA, Frysinger RC, Patrie JT, Huss DS, Currie LJ, et al. UPDRS activity of daily living score as a marker of Parkinson's disease progression. Mov Disord. 2009;24(2):224–230. doi: 10.1002/mds.22335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez‐Martin P, et al. Movement Disorder Society‐sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS‐UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23(15):2129–2170. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keus SH, Bloem BR, Hendriks EJ, Bredero‐Cohen AB, Munneke M. Evidence‐based analysis of physical therapy in Parkinson's disease with recommendations for practice and research. Mov Disord. 2007;22(4):451–460. doi: 10.1002/mds.21244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brusse KJ, Zimdars S, Zalewski KR, Steffen TM. Testing functional performance in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2005;85(2):134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(1):33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997;15(2):300–308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Won J, Cho K. The validity and reliability of Korean version of Lawton IADL Index. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2005;9(1):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nijkrake MJ, Keus SH, Quist-Anholts GW, Overeem S, De Roode MH, Lindeboom R, et al. Evaluation of a Patient-Specific Index as an outcome measure for physiotherapy in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45(4):507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Group TCM. Martínez-Martin P, Gil-Nagel A, Gracia LM, Gómez JB, Martínez-Sarriés F, et al. Intermediate scale for assessment of Parkinson's disease. Characteristics and structure. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 1995;1(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/1353-8020(95)00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz S. Assessing self‐maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31(12):721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung HY, Park BK, Shin HS, Kang YK, Pyun SB, Paik NJ, et al. Development of the Korean version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI): multi-center study for subjects with stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2007;31(3):283–297. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SY, Won CW, Rho YG, Yoon JL. The validity and reliability of Korean version of Karz ADL index. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2004;8(2):62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, Scheltens P, Uitdehaag BM. A systematic review of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales in dementia: room for improvement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(1):7–12. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.155838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn H, Yum T, Shin Y, Kim K, Yoon D, Chung K. A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory in Korea. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1986;25(3):487–500. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siddiqui M, Rast S, Lynn M, Auchus A, Pfeiffer R. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: a comprehensive symptom survey. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8(4):277–284. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(01)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Boer AG, Wijker W, Speelman JD, de Haes JC. Quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: development of a questionnaire. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(1):70–74. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinnell C, Hurt CS, Landau S, Brown RG, Samuel M. Nonmotor versus motor symptoms: how much do they matter to health status in Parkinson's disease? Mov Disord. 2012;27(2):236–241. doi: 10.1002/mds.23961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting our findings is contained within the manuscript.