Abstract

The murine thymus produces discrete γδ T cell subsets making either interferon-γ (IFN--γ) or interleukin 17 (IL-17), but the role of the TCR in this developmental process remains controversial. Here we show that mice haploinsufficient for both Cd3g and Cd3d (CD3DH, for CD3 double haploinsufficient) have reduced TCR expression and signaling strength selectively on γδ T cells. CD3DH mice had normal numbers and phenotype of αβ thymocyte subsets but impaired differentiation of fetal Vγ6+ (but not Vγ4+) IL-17-producing γδ T cells and a marked depletion of IFN-γ-producing CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ T cells throughout ontogeny. Adult CD3DH mice showed reduced peripheral IFN-γ+ γδ T cells and were resistant to experimental cerebral malaria. Thus, TCR signal strength within specific thymic developmental windows is a major determinant of the generation of proinflammatory γδ T cell subsets and their impact on pathophysiology.

Proinflammatory cytokines orchestrate protective immune responses to pathogens and tumors, but are also responsible for tissue-damaging inflammation and autoimmunity. Among various cellular sources, γδ T cells have emerged as major producers of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and/ or interleukin 17 (IL-17) in several diseases. On one hand, IFN-γ production by γδ T cells underlies protective responses to infections1, as well as tumor immunity2, but, conversely, it is associated with susceptibility to severe malaria3. On the other hand, IL-17 secretion by γδ T cells is a key defense mechanism against various bacterial infections, such as Staphylococcus aureus4 or Listeria monocytogenes4, 5, but is also a critical component of inflammatory and autoimmune syndromes like psoriasis6-8, colitis9, chronic granulomatous disease10, ischemic brain inflammation11 and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis12-14.

The non-redundant roles of IFN-γ-producing (IFN-γ+) and IL-17-producing (IL-17+ ) γδ T cells are tightly linked to “developmental pre-programming” in the murine thymus15. Whereas conventional effector CD4+ T cells differentiate in peripheral lymphoid organs in response to antigen and additional environmental cues, γδ T cells complete their functional maturation in the thymus. On the basis of CD27 and CCR6 expression, the murine thymus generates discrete populations of IFN-γ+ and IL-17+ γδ T cells 16, 12, 17. Importantly, these subpopulations have different functions: for example, CD27− IL-17+ γδ T cells promote tumor cell growth18, 19 whereas CD27+ IFN-γ+ γδ T cells inhibit it2, 20. It is therefore critical to understand how distinct functional γδ T cell subsets are generated and regulated.

Given its pivotal role in thymocyte development and selection, the T cell receptor (TCR) is a likely determinant of the functional differentiation of γδ T cells15. It was shown that T10/T22 tetramer-specific γδ T cells, which account for ~0.4% of peripheral γδ T cells, produced IL-17 or IFN-γ in the absence or presence, respectively, of thymic T10/T22 expression12. Consistent with this, thymic selection drives dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) that populate the mouse epidermis towards IFN-γ but away from IL-17 production21. However, SKG mice, which are hypomorphic for the TCR signal-transducing kinase ZAP70, retaining only 10% of its signaling ability, showed impaired development of IL-17+ γδ T cells22. As such, the role of TCR signal “strength” in the development of proinflammatory γδ T cell subsets remains unclear.

TCR signal strength is known to control the earliest stage of γδ T cell development, i.e., lineage commitment23. The manipulation of signal transduction in TCR transgenic T cells influenced the γδ versus αβ thymocyte fate24, 25, with γδ T cells requiring stronger TCR signaling than αβ T cells to develop. However, the impact on subsequent maturation of γδ T cells, particularly IFN-γ+ versus IL-17+ γδ T cells, was not assessed. On the other hand, models based on a single transgenic TCR may not be ideal to answer this question, because γδ T cell development is tightly linked to the dynamics of TCR rearrangements during ontogeny. Indeed, “developmental waves” with distinct TCR gene usage populate different peripheral tissues, and distinct TCRγ chain variable region (Vγ) repertoires can have significant biases towards either IFN-γ or IL-17 production16, 26. For example, of the two main γδ T cell subsets in peripheral lymphoid organs, Vγ1+ T cells preferentially secrete IFN-γ, whereas Vγ4+ T cells are biased towards IL-1716, 26. In addition, Vγ5+ T cells generated around embryonic days E15-E16 do not secrete IL-17, while this cytokine is abundantly produced by Vγ6+ T cells that differentiate at E17-E18. Moreover, in-depth transcriptional profiling of γδ thymocyte subsets by the Immunological Genome Project (www.immgen.org) demonstrated a divergence between the transcriptional networks of IL-17 -biased Vγ6+ and Vγ4+ T cells versus IFN-γ-biased Vγ5+ and Vγ1+ T cells27, 28.

The association between certain γδ TCR repertoires and differential IFN-γ or IL-17 production26 suggests that TCR signaling is a major determinant of the functional differentiation of γδ T cells in the thymus. However, testing this hypothesis has been hampered by the lack of mouse models that specifically interfere with TCRγδ signaling in vivo. Here we describe a selective defect in the surface expression of TCRγδ, but not TCRαβ, in Cd3g+/− Cd3d+/− mice (CD3DH, for CD3 double haploinsufficient), and show that reduced TCRγδ signaling impacts on the differentiation of discrete subsets of IFN-γ and IL-17-producing γδ T cells during thymic ontogeny with pathological consequences.

Results

Cd3d+/−Cd3g+/− mice show reduced TCR signaling in γδ T cells

During the screening of various lines of (single or double) haploinsufficient CD3 mutants, we observed that Cd3d+/−Cd3g+/− mice (hereafter CD3DH, for double haploinsufficient) had markedly lower cell surface expression of TCRγδ and CD3ε (Fig. 1a,b) and reduced γδ thymocyte numbers (Fig. 1c). This reduction was not observed in single haploinsufficient, Cd3d+/− or Cd3g+/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a), and was more severe than that observed in CD3δ-deficient mice29 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The reduced numbers of γδ thymocytes in CD3DH mice were not due to increased cell death (Supplementary Fig. 1c), suggesting that lower TCRγδ expression impaired γδ T cell development, as reported in transgenic models24, 25. CD3DH γδ thymocytes remained mostly CD4− CD8− (data not shown), thus excluding diversion into the αβ lineage. On the other hand, TCRαβ expression was not affected, and αβ thymocyte development proceeded normally in CD3DH mice (Fig. 1d-f). Consistent with normal TCRαβ signaling and selection, the generation of agonist-selected Foxp3+ CD4+ and CD1d-restricted NKT cells was similar to wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 1d,e).

Figure 1. γδ T cells from CD3DH mice show reduced TCRγδ expression and signaling.

(a) Flow cytometry showing the CD3ε vs TCRδ phenotype of thymocytes from one-week old wildt-ype (WT) or Cd3g+/− Cd3d+/− (CD3DH) mice (n = 10 per group). Numbers within outlined areas or quadrants indicate % cells in each throughout. (b-f) TCRγδ MFI (b) and γδ thymocyte numbers (c) gated as in (a), CD8 vs CD4 phenotype of thymocytes (n = 3 per group of adult mice) (d), TCRαβ MFI (e) and absolute numbers of TCRβ+CD3+ thymocytes (f). (g-i) Flow cytometry showing expression of the indicated agonist selection and maturation markers in gated TCRδ+CD3+CD27+ thymocytes (g), of CD69 and CD25 in sorted TCRδ+CD3+CD27+ spleen cells stimulated with plate-coated α-CD3ε mAb for 24h (h), of phosphorylated Erk1/Erk2 (empty histograms) vs isotype-matched background staining (filled histograms) in sorted TCRδ+CD3+CD27+ lymph node cells stimulated for 5 min with soluble α-CD3ε mAb (i). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (j, k) Flow cytometry showing comparative TCRγδ MFI (j) and Thy-1.1( WT-derived) vs Thy-1.2 (CD3DH-derived) fractions among gated TCRδ+CD3+ and CD4+CD3+ thymocytes (k) from 1:1 mixed WT:CD3DH bone marrow chimeras. Each symbol indicates one host, either RAG2−/− (squares) or TCRδ−/− (triangles). In (b,c) and (e,f), dots represent individuals and horizontal lines mean ± s.d. NS, not significant; *P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

To characterize the downstream effects of reduced TCRγδ expression we assessed the expression of agonist selection markers, namely CD73, a signature of TCRγδ signaling during thymic development30, and CD5, a stable indicator of TCR signal strength31, as well as the maturation markers CD122 and CD4412, 15, 17. All were markedly reduced in γδ thymocytes from CD3DH compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 1g). Upon TCR stimulation, the activation markers CD69 and CD25 were also decreased in peripheral (splenic) CD3DH γδ T cells (Fig. 1h). Moreover, CD3DH γδ T cells had lower TCR responsiveness in terms of ERK (Fig. 1i) and AKT (Supplementary Fig. 2a) activation or calcium mobilization (Supplementary Fig. 2b) compared to wild-type γδ T cells. These data indicate that lower surface TCRγδ expression in Cd3d+/−Cd3g+/− mice impairs signal transduction and downstream TCR-dependent processes.

To test whether the phenotype of γδ T cells in CD3DH mice was cell-intrinsic, we established mixed (1:1) bone marrow (BM) chimeras by transferring CD3DH (Thy-1.2) and wild-type (Thy-1.1) whole BM cells into either TCRδ-deficient or RAG2-deficient hosts. In both hosts we observed reduced TCRγδ expression in CD3DH-derived γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1j), which consistently accounted for a minor fraction of the total γδ thymocyte pool, compared to wild-type γδ thymocytes. In contrast, αβ thymocytes were evenly generated from CD3DH or wild-type precursors (Fig. 1k), indicating that CD3DH progenitors are outcompeted by wild-type precursors for γδ, but not αβ T cell development. Of note, this disadvantage could be compensated by using a 1:9 WT: CD3DH ratio (Supplementary Fig. 3), which indicated that CD3DH progenitors can generate γδ thymocytes albeit with reduced potency compared to wild-type precursors. Thus, haploinsufficiency for both Cd3d and Cd3g results in lower TCRγδ expression levels and signaling and reduced numbers of γδ thymocytes.

Impaired differentiation of IL-17+ and IFN-γ+ γδ T cell subsets

We next analyzed the functional differentiation of γδ T cell subsets. Development of CD27+ and CD27− γδ T cells was observed during the embryonic stages and continued into adulthood (Fig. 2a), as previously reported. 16 Both IFN-γ+ and IL-17+ γδ thymocytes were observed in reduced frequencies in CD3DH compared to wild-type E18 embryos (Fig. 2b, c). Whereas the reduction in IFN-γ+ γδ thymocytes was maintained after birth into adulthood, the frequency of IL-17+ γδ thymocytes in CD3DH mice normalized to wild-type levels between 1 and 6 weeks of age (Fig. 2b-d). This coincided with a switch in TCR Vγ usage: most IL-17+ γδ T cells are Vγ1− Vγ4-(validated as Vγ6+ by GL3/ 17D1 antibody staining as in18, not shown) in E18 embryos and neonates, and Vγ4+ from week 1 onwards (Fig. 2e). Of note, IL-17+ Vγ6+ cells are generated exclusively during embryonic life32. Importantly, only Vγ6+ but not Vγ4+ thymocytes showed reduced IL-17 production in CD3DH mice (Fig. 2f). These data suggest that the effector γδ T cell subsets generated within distinct developmental windows, as marked by particular Vγ usage, have distinct TCR signal strength requirements.

Figure 2. CD3DH mice show impaired differentiation of IL-17+ and IFN-γ+ γδ T cells within selective windows of TCR Vγ usage.

(a-c) Flow cytometry at various developmental stages showing representative surface CD27 expression in gated CD3+TCRδ+ thymocytes (n = 10 per mice group) (a), intracellular IL-17 in CD3+TCRδ+CD27− thymocytes ( b ) and IFN-γ expression in CD3+TCRδ+ CD27+ thymocytes (c) from WT or CD3DH mice following stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Data are representative of two to four experiments per developmental stage. Numbers indicate the % cells in the marked region. (d) Percent CD27−IL-17+ (top) and CD27+IFN-γ+ (bottom) γδ T cells in WT and CD3DH mice (n = 5 per group) as determined in (b) and (c), respectively. Data shown are the mean +/− s.d. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). (e) Vγ usage by CD27−IL-17+ or CD27+IFN-γ+ γδ T cells at various developmental stages (n = 7 per group), as determined by flow cytometry. (f) Flow cytometry showing intracellular IL-17 expression in CD3+TCRδ+CD27− thymocytes from E18 WT or CD3DH mice following stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Numbers indicate % cells in the marked region.

Transcriptional signatures of TCR signal strength in γδ T cells

Because developmental programming of γδ T cells is set at the transcriptional level27, 33, 34, we performed transcriptome-wide analysis of sorted total γδ thymocytes from CD3DH or wild-type mice at E18 of embryonic development or at 6-week of age. This analysis showed highly dynamic patterns of gene expression during ontogeny (Fig. 3a). Among the mRNAs upregulated in γδ thymocytes from E18 to adult in wild-type mice, those linked to IFN-γ production were generally impaired in CD3DH γδ thymocytes, such as Nr4a3, Nr4a2 and Bcl2a116, 34, 35, the transcription factors Egr2, Egr3 and Id3, which are major suppressors of the IL-17 differentiation pathway21, and Nfkbiz (which encodes the transcription factor IκBζ)36, Tnfrsf18 (encoding GITR), Gp49a and Lilrb4 (encoding Gp49b)37, which are involved in the regulation of IFN-γ production (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Figure 3. Transcriptional signatures of TCR signal strength in γδ thymocytes.

(a) Microarray heatmap of differentially expressed genes during ontogeny in sorted CD3+TCRδ+ γδ thymocytes of WT or CD3DH mice (>2-fold adult/fetal between week 5-7 and E18). (b) Fold expression by real-time RT-PCR (in arbitrary units normalized to the housekeeping gene Hprt) of Egr2, Egr3, Nt5e (encoding CD73), Sox4, Il23r and Ilr1 genes by sorted CD3+TCRδ+γδ thymocytes from WT or CD3DH mice before and after 16h stimulation with α-CD3ε mAb (10 μg/ml). Data shown are the mean +/− s.d. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

On the other hand, key type 17 genes, such as Il17a, Il17f and Il23r 13,33, which are highly expressed in fetal γδ thymocytes and reduced in adult γδ thymocytes in wild-type mice, were downregulated in CD3DH γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3a). Both wild-type and CD3DH γδ thymocytes downregulated the embryonically rearranged TCRs, such as Vγ5 and Vγ6, as well as the transcription factor PLZF (encoded by Zbtb16), which is characteristic of fetal γδ thymocytes27(Fig. 3a).

The type 17 signature genes Sox 4 and Sox13 (ref 27, 28) were greatly reduced in embryonic Vγ6+, but not Vγ4+ CD3DH (compared to wild-type) thymocytes (Supplementary Fig. 4b), indicating that the IL-17+Vγ6+and IL-17+Vγ4+ thymocyte subsets have.distinct developmental TCR signal strength requirements. Of note, the expression of Tbx21 (which encodes T- bet) and Rorc (which encodes RORγt), which transcriptionally regulate Ifng and Il17a expression respectively, was not affected in CD3DH compared to wild-type γδ thymocytes (data not shown).

Next, for a TCR-mediated gain-of-function approach, we stimulated total γδ thymocytes from adult CD3DH or wild-type mice with saturating amounts of anti-CD3ε mAb for 16 hours, to achieve crosslinking of all available T C R complexes on the cell surface. We observed an upregulation of Egr2 and Egr3 expression in wild-type γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3b), consistent with their induction by strong TCR signals21. Egr2 and Egr3 upregulation was also observed in stimulated CD3DH γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3b), suggesting that increasing γδ TCR signaling can rescue the expression of IFN-γ-associated transcriptional signatures in CD3DH γδ thymocytes. In addition, anti-CD3ε mAb stimulation downregulated the type 17 signature genes, such as Sox428, Il23r and Il1r113, 33, 38, in both wild-type and CD3DH γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3b). Collectively, these data suggest that strong TCR signals are required to promote IFN-γ at the expense of IL-17 production by adult γδ thymocytes.

CD3DH mice lack IFN-γhi CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocytes

We next tested if the deficiency in IFN-γ expression in γδ thymocytes from CD3DH mice involved the depletion of a specific γδ T cell subset committed to IFN-γ production. Thus, we analyzed the expression of CD122 (ref12) and NK1.1 (ref17,30), two markers previously associated with IFN-γ+ γδ T cells, on adult CD27+ γδ T cells. We detected a CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ T cell population in the wild-type thymus that was absent in CD3DH mice (Fig. 4a, b). CD122+ NK1.1− γδ T cells, likely precursors of CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ T cells, were also reduced in the CD3DH thymus compared to wild-type (Fig. 4a). The Vγ repertoire changed from Vγ4-biased to Vγ1-enriched between the CD122− and the more mature CD122+ γδ T cells in wild-type thymi (Fig. 4c), suggesting that TCR selection shapes the mature γδ thymocyte pool. Furthermore, consistent with a requirement for strong TCR signaling, wild-type CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocytes had high expression of the selection markers CD44, CD73 and CD45RB, which were not detected on CD122− γδ thymocytes (Fig. 4d). Importantly, wild-type CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocytes had the highest expression of IFN-γ (Fig. 4d), suggesting that the high IFN-γ---producing γδ T cells have a differentiation defect in CD3DH mice. Furthermore, in mixed WT:CD3DH BM chimeras, CD27+ CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocytes were exclusively generated from wild-type progenitors (Fig. 4e). This observation was made in both 1:1 and 1:9 chimeras (Fig. 4e), indicating a strong competitive disadvantage of CD3DH precursors along this developmental pathway.

Figure 4. CD3DH mice lack IFN-γ hi CD122+ NK1.1+ thymocytes that are rescued by CD3 crosslinking in vivo.

(a) Flow cytometry showing representative NK1.1 vs CD122 expression in TCRδ+CD3+CD27+ thymocytes isolated from adult WT or CD3DH mice (n = 10 per group). Numbers indicate % cells in each quadrant. (b) Frequencies (left) and total numbers (right) of TCRδ+CD3+CD27+CD122+NK1.1+ thymocytes. Each dot represents an individual mouse; bars indicate the mean +/− s.d. *P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test) throughout. (c, d) Flow cytometry showing representative Vγ1 vs Vγ4 chain usage (c) and surface CD44, CD73, CD45RB or intracellular IFN-γ production (d) by the indicated gated TCRδ+CD3+CD27+ thymocyte subsets from adult WT mice (n = 5 per group). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (e) Flow cytometry showing representative NK1.1 vs CD122 expression (top) within Thy-1.1+ ( WT-derived) or Thy-1.2+ (CD3DH-derived) fractions (bottom) of TCRδ+CD3+CD27+CD122+NK1.1+ thymocytes from 1:1 or 1:9 mixed bone marrow chimeras. Each symbol indicates one host, either RAG2−/− (squares) or TCRδ−/− (triangles). (f, g) Flow cytometry showing representative NK1.1 vs CD122 expression (f) and % (left) and numbers (right) of TCRγδ+CD3+CD27+ CD122+NK1.1+ thymocytes (g) in WT or CD3DH mice, 5 days after i.p. injection of α-CD3 mAb 17A2 ( n = 3 per group). Each dot represents an individual mouse; bars indicate the mean +/− s.d.

We next aimed to rescue the generation of CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocytes in CD3DH mice by cross-linking their TCR complex in vivo. Intraperitoneal injection of the 17A2 antibody, which cross-links CD3εγ dimers, rescued CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocyte development in CD3DH mice, leading to frequencies similar to wild-type mice (Fig. 4f, g). Moreover, wild-type mice treated with 17A2 showed an increase in CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocytes compared to untreated wild-type mice (Fig. 4a, f). These data indicate that strong TCR signaling promotes (and is required for) the development of the IFN-γhi CD27+ CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ thymocyte subset.

Reduced IFN-γ+ γδ splenocytes and resistance to cerebral malaria

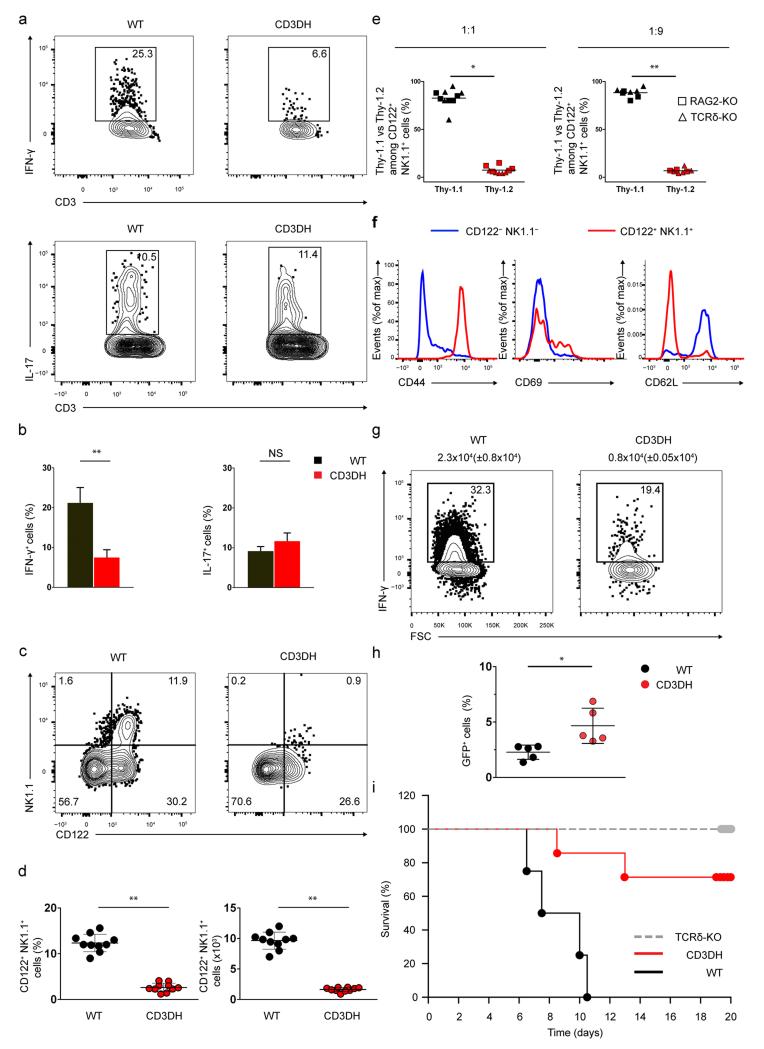

We next investigated the consequences of reduced γδ TCR signaling in CD3DH mice on peripheral γδ T cells. Upon ex vivo PMA+ionomycin stimulation, CD3DH splenocytes showed reduced CD27+ IFN-γ+ but normal CD27− IL-17+ γδ T cell frequencies compared to wild-type splenocytes (Fig. 5a, b). In contrast, CD3DH CD4+ αβ T cells differentiated normally into Th1 cells when activated in the presence of IL- 12 (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating that the IFN-γ defect of CD3DH mice was selective for γδ T cells. Moreover, CD27+ CD122+ NK1.1+ CD44+ γδ splenocytes were absent in CD3DH compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 5c-f). This was also observed in competitive WT:CD3DH BM chimeras, both at 1:1 and 1:9 ratios (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5. CD3DH mice show reduced peripheral IFN-γ+ γδ T cells and are resistant to cerebral malaria.

(a,b) Intracellular IFN-γ (top) or IL-17 (bottom) expression in CD27+ or CD27− TCRδ+CD3+ adult mice splenocytes, respectively, stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (a). Numbers indicate % of cells in the marked region, which are shown for n = 5 per group in (b). (c, d) NK1.1 vs CD122 expression in TCRδ+CD3+CD27+ adult mice splenocytes (c). Numbers indicate % of cells in each quadrant, which are shown in (d) for n = 20 per group as % (left) or total numbers (right). (e) Thy-1.1 (WT-derived) vs Thy-1.2 ( CD3DH-derived) fractions among TCRδ+CD3+CD27+CD122+NK1.1+ splenocytes from 1:1 or 1:9 mixed WT:CD3DH BM chimeras. Each symbol indicates one host, either RAG2−/− (squares) or TCRδ−/− (triangles). (f) Comparative surface expression of the indicated markers in CD122−NK1.1− vs CD122+NK1.1+ cells gated on WT TCRγδ+CD3+ CD27+ splenocytes. (g, h) Intracellular IFN-γ expression (after PMA and ionomycin stimulation) in TCRγδ+CD3+CD27+ splenocytes sorted 5 days after infection with Plasmodium berghei ANKA sporozoites. Numbers above plots indicate mean +/− s.d. absolute counts of IFN-γ+ γδ cells (g). Parasitemia as % blood GFP+ cells 5 days after infection (h). (i) Survival curves of n = 10 mice infected as in (g) in two independent experiments. Data in (a) and (e) are representative of n = 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate s.d. of the mean and dots represent individual mice throughout. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

We next assessed the physiological importance of IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells in a model of cerebral malaria, which in C57BL/6 mice induces IFN-γ-dependent pathology39 and in both mice and humans3 requires a major contribution from γδ T cells. We induced experimental cerebral malaria with Plasmodium berghei ANKA sporozoites, thus establishing a liver-stage infection before spreading to the blood, which is the symptomatic stage. Whereas wild-type mice presented an abundant IFN-γ+ γδ T cell population in the spleen at day 5 post-infection (blood stage), this was markedly reduced in CD3DH mice (Fig. 5g), and associated with higher parasitemia (measured as % of infected red blood cells) compared to infected wild-type mice (Fig. 5h). Neurological symptoms appeared in wild-type mice around day 6 post-infection and became fatal in all animals by days 7-10 (Fig. 5i). By contrast, γδ T cell-deficient (TCRδ-deficient), as well as most CD3DH mice remained healthy and survived (Fig. 5i). These data demonstrate that IFN-γ+ γδ T cells make mice highly susceptible to fatal inflammatory syndromes like severe malaria.

Discussion

The reduced TCRγδ expression on the surface of γδ thymocytes in CD3DH mice allowed us to examine a diverse, polyclonal TCRγδ repertoire, which is highly valuable given the association between specific TCR gene usage and functional differentiation biases26. Our results suggest that distinct developmental γδ T cell subsets defined by TCRVG rearrangement and Vγ usage have distinct TCR signal strength requirements for differentiation into IFN-γ- or IL-17-producing cells.

CD3δ was shown to be absent from mouse mature TCRγδ complexes42, 43, which raises the question how it impacts surface TCRγδ expression. As we found no evidence for the presence of CD3δ on the surface of γδ thymocytes (data not shown), we are currently investigating the possibility that CD3δ transiently participates in TCRγδ assembly. Also, changes in the relative intracellular amounts of CD3 chains as observed in CD3DH mice could cause abnormal glycosylation of CD3δ 44, 45 (data not shown) and/or CD3γ46, which in turn could impair the assembly and stability of nascent TCR complexes, and ultimately their surface expression and signaling 41, 46. TCR signaling strength impacts thymic commitment to the αβ versus γδ lineages23-25. Consistent with this, CD3DH mice showed reduced numbers of total γδ thymocytes, including loss of CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ T cells (expressing high IFN-γ levels). The number and frequencies of αβ T cell subsets, including thymic regulatory ( Treg) and invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, was normal in CD3DH mice, although the repertoire of TCRαβ+ subpopulations was not assessed. However, the expression of the αβ TCR was normal in developing CD3DH thymocytes, indicating that the reduction in TCR expression was specific to γδ thymocytes.

Interestingly, whereas IL-17+ Vγ6+ cells were underrepresented in CD3DH mice, their IL-17+ Vγ4+ counterparts were not affected, consistent with distinct developmental requirements for the two IL-17-producing γδ T cell subsets32. Vγ6+ thymocytes have been shown to outcompete Vγ4+ thymocytes when reconstituting the dermis of γδ T cell-deficient mice8, and whereas fetal-derived (and thymically programmed) Vγ6+ T cells were shown to be resident in the dermis, adult BM-derived Vγ4+ T cells seem to depend on extrathymic signals to migrate to the skin. Thus, by differentially controlling tissue homing properties, thymic programming may determine the pathophysiological contributions of discrete γδ T cell subsets. Consistent with this, Vγ4+ T cells represent the major source of IL-17 in psoriasis-like inflammation8, 32, as well as in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis13 and collagen-induced arthritis48, whereas Vγ6+ T cells are more frequent in Listeria infection5 and ovarian cancer18.

The observation that fetal-derived and adult IL-17-producing γδ T cells have distinct TCR signaling requirements could not be obtained using the available ( Vγ4-based) transgenic TCRγδ models, and resolves previous controversies on the TCR (in)dependence of IL-17+ γδ T cell development12, 21, 22, 28. Namely, our data indicates that Vγ6+, but not Vγ4+, thymocytes depend on strong TCR signals for functional differentiation, which in turn warrants investigation into their respective ligand engagement requirements.

In addition to ligand engagement, distinct signaling cascades downstream of the TCRγδ may differentially affect γδ T cell subsets. It will be important to establish if TCRγδ signaling is perceived mostly quantitatively or, rather, qualitatively based on the engagement of distinct signaling pathways, such as ERK-MAPK or PI3K-AKT (Nital Sumaria, B.S.-S. and D. J. P., unpublished results). Further downstream in cellular programming, our transcriptional analysis of fetal and adult total γδ thymocytes stages showed that CD3DH γδ thymocytes efficiently downregulated the IL-17 program, but were deficient in upregulating the IFN-γ pathway between fetal and adult stages. Particularly affected were the transcription factors Egr2, Egr3 and Id3, which are induced by agonist TCR signaling21, 50, and may be required to suppress a “default” RORγt-dependent IL-17 program and maximize IFN-γ production in γδ thymocytes. This would be consistent with both the repression of the IL-17 pathway in Vγ5+ DETC development21 and the depletion, in CD3DH mice, of Vγ1-biased CD27+ CD122+ NK1.1+ γδ T cells, the subset expressing the highest IFN-γ on a per cell basis.

Interestingly, the transcription factors that control Ifng and Il17a expression, T-bet and RORγt, were normally expressed in CD3DH γδ T cell subsets, suggesting that the γδ T cell differentiation phenotype in these mice derives from mechanisms downstream of T-bet or RORγt expression. This is in agreement with normal expression of these transcription factors in γδ thymocytes deficient for the TCR signal transducer Itk28. We therefore propose that a major function of TCRγδ signaling is to select preprogrammed precursors, which could resemble innate lymphoid cells (ILC), for differentiation into effector cells making IFN-γ or IL-17. Future studies on the functional similarities and differences between ILC and γδ T cell subsets may contribute to understanding the evolutionary conservation of these innate-like lymphocytes and their therapeutic potential for infectious or inflammatory diseases and cancer20.

Online methods

Mice

Adult mice were used at 4–8 weeks of age. Embryos were obtained by the setting up of timed pregnancies. C57BL/6 (WT) mice were from Charles River Laboratories. CD3γ−/− mice have been previously described51, and were kindly given by Dr. D. Kappes (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia). CD3δ−/− have been previously described29 and were yield by Dr. I. Luescher (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Lausanne). Double heterozygotes (CD3DH) were obtained by crossing CD3γ−/− males with CD3δ−/− females. For the studies, both males and females were used. Mice were bred and maintained in the pathogen–free animal facilities of the Instituto de Medicina Molecular (Lisbon) and Animalario Universidad Complutense (Madrid). All experiments involving animals were done in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines.. Experimental procedures were ethically approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of Universidad Complutense and Comunidad de Madrid, and by the institutional animal welfare body – ORBEA-iMM – and by the DGAV (Portuguese competent authority for animal protection), all in accordance with Directive 2010/63/EU.

Bone marrow chimeras

Rag2−/− or Tcrd−/− mice were lethally irradiated (900 rad), and the next day injected intravenously with a total of 107 whole bone marrow cells of mixed (1:1 or 1:9) WT.Thy-1.1 and CD3DH.Thy-1.2 origin. Chimeras were kept on antibiotics-containing water (2% Bactrim; Roche) for the first 4 weeks post-irradiation. The hematopoietic compartment was allowed to reconstitute for 6 weeks before organs were harvested for flow cytometry analysis.

Cell preparations

Thymuses, lymph nodes and spleens were homogenized and washed in RPMI medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS. Splenocytes were depleted from erythrocytes using the Red Blood Cell Lysis buffer 1x (Biolegend).

Monoclonal antibodies

Listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

For cell surface staining, thymocytes, erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes or lymph node cells were incubated 30 min with saturating concentrations of mAbs identified above. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) (50ng/mL) and ionomycin (1μg/mL), in the presence of Brefeldin A (10μg/mL) (all from Sigma) for 4h at 37°C. Cells were stained for the identified above cell surface markers, fixed 30min at 4°C and permeabilized with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer set (eBioscience) in the presence of anti-CD16/CD32 (93) (eBioscience) for 15 min at 4°C, and finally incubated for 1h at room temperature with identified above cytokine-specific Abs in permeabilization buffer. Samples were acquired using FACSFortessa (BD Biosciences). Data were analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Live indicated subsets were electronically sorted when indicated using FACSAria (BD Biosciences).

Cell culture

For early activation markers, cells were incubated for 24h on plate-bound anti-CD3e (10 mg/ml) and anlalyzed by flow citometry. For phosphorylated molecules downstream of TCR vs isotype-matched control antibody, sorted lymph node cells were stimulated for 5 min with soluble anti-CD3ε (10 μg/ml) then fixed 30min at 4°C and permeabilized with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer set (eBioscience) in the presence of anti CD16/CD32 Fc Block (93) (eBioscience) for 30min at room temperature, and finally incubated for 1h at room temperature with identified above anti-p-ERK Abs in permeabilization buffer. For Th1 polarization CD4+ αβ T cells were isolated by flow cytometry and incubated for 4 days on plate-bound anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 (5ng/ml each). When indicated (Th1 cocktail), the following cytokines and neutralizing antibody were added to the culture milieu: IL-2 (10 ng/ml; Preprotech), IL-12 (50 ng/ml; Preprotech) and anti-IL-4 (11B11) (10 μg/mL; eBiosciences).

Malaria infection

Mice were infected as described52.

RNA Isolation, cDNA Production, and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentration and purity were determined using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Life Technologies). Primers were either designed manually or by using the Universal ProbeLibrary Assay Design Center from Roche (www.roche-applied-science.com). Sequences are available upon request. Analysis of the quantitative PCR results was performed using the ViiA 7 software v1.2 (Applied Biosystems; Life Technologies).

Microarray

Accession code GSE71637. All the microarray data analysis was done using R and several packages available from CRAN53 and Bioconductor54. The raw data (CEL files) were normalized and summarized with the Robust MultiArray Average method implemented in the ‘oligo’ package55. Variations in gene expression levels were determined using ‘limma’ package56 and only genes with fold-change higher than 2 were considered for downstream analysis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between populations was assessed with the Student’s t-test; P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Animal sample size was chosen to ensure significance of t-test. No animals were excluded. No randomization or blinding was performed. Data met normal distribution with similar variance between groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Serre, J. Martins, N. Schmolka, A. Amorim, V. Z. Luís and M. M. Mota (all iMM Lisboa); and B. Garcillán, D. de Juan, M. Mazariegos, M. Sanz-Rodríguez and S. Diaz-Castroverde (U. Complutense) for help and advice; A. Hayday (King’s College London) for insightful discussions; and the staff of our animal and flow cytometry facilities for technical assistance. This work was funded by the European Research Council (StG_260352 and CoG_646701) to B.S.-S.; MINECO (SAF2011-24235 and BES-2012-055054), CAM (S2010/ BMD-2316/2326) and Lair (2012/0070) to J.R.R.; and FIS PI11/02198 and MINECO SAF2014-54708-R to E.F.-M.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Microarray data, GSE71637.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wang T, et al. IFN-gamma-producing gamma delta T cells help control murine West Nile virus infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:2524–2531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao Y, et al. Gamma delta T cells provide an early source of interferon gamma in tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2003;198:433–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagannathan P, et al. Loss and dysfunction of Vdelta2(+) gammadelta T cells are associated with clinical tolerance to malaria. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:251ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho JS, et al. IL-17 is essential for host defense against cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1762–1773. doi: 10.1172/JCI40891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheridan BS, et al. gammadelta T cells exhibit multifunctional and protective memory in intestinal tissues. Immunity. 2013;39:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai Y, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pantelyushin S, et al. Rorgammat+ innate lymphocytes and gammadelta T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2252–2256. doi: 10.1172/JCI61862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y, et al. Differential developmental requirement and peripheral regulation for dermal Vgamma4 and Vgamma6T17 cells in health and inflammation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3986. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SG, et al. T regulatory cells maintain intestinal homeostasis by suppressing gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2010;33:791–803. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romani L, et al. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature. 2008;451:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nature06471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shichita T, et al. Pivotal role of cerebral interleukin-17-producing gammadeltaT cells in the delayed phase of ischemic brain injury. Nat Med. 2009;15:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nm.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen KD, et al. Thymic selection determines gammadelta T cell effector fate: antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon gamma. Immunity. 2008;29:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton CE, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petermann F, et al. gammadelta T cells enhance autoimmunity by restraining regulatory T cell responses via an interleukin-23-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 2010;33:351–363. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prinz I, Silva-Santos B, Pennington DJ. Functional development of gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1988–1994. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribot JC, et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-gamma- and interleukin 17-producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:427–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas JD, et al. CCR6 and NK1.1 distinguish between IL-17A and IFN--gamma-producing gammadelta effector T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3488–3497. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rei M, et al. Murine CD27(-) Vgamma6(+) gammadelta T cells producing IL-17A promote ovarian cancer growth via mobilization of protumor small peritoneal macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3562–3570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403424111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu P, et al. gammadeltaT17 cells promote the accumulation and expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human colorectal cancer. Immunity. 2014;40:785–800. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva-Santos B, Serre K, Norell H. Gamma-delta T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:683–691. doi: 10.1038/nri3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turchinovich G, Hayday AC. Skint-1 identifies a common molecular mechanism for the development of interferon-gamma-secreting versus interleukin-17-secreting gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2011;35:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wencker M, et al. Innate-like T cells straddle innate and adaptive immunity by altering antigen-receptor responsiveness. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:80–87. doi: 10.1038/ni.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciofani M, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Determining gammadelta versus alphass T cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:657–663. doi: 10.1038/nri2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haks MC, et al. Attenuation of gammadeltaTCR signaling efficiently diverts thymocytes to the alphabeta lineage. Immunity. 2005;22:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes SM, Li L, Love PE. TCR signal strength influences alphabeta/gammadelta lineage fate. Immunity. 2005;22:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien RL, Born WK. gammadelta T cell subsets: a link between TCR and function? Semin Immunol. 2010;22:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narayan K, et al. Intrathymic programming of effector fates in three molecularly distinct gammadelta T cell subtypes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:511–518. doi: 10.1038/ni.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malhotra N, et al. A network of high-mobility group box transcription factors programs innate interleukin-17 production. Immunity. 2013;38:681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dave VP, et al. CD3 delta deficiency arrests development of the alpha beta but not the gamma delta T cell lineage. EMBO J. 1997;16:1360–1370. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffey F, et al. The TCR ligand-inducible expression of CD73 marks gammadelta lineage commitment and a metastable intermediate in effector specification. J Exp Med. 2014;211:329–343. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azzam HS, et al. CD5 expression is developmentally regulated by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and TCR avidity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2301–2311. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas JD, et al. Development of interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells is restricted to a functional embryonic wave. Immunity. 2012;37:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmolka N, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptional signatures of stable versus plastic differentiation of proinflammatory gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1093–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmolka N, Wencker M, Hayday AC, Silva-Santos B. Epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of gammadelta T cell differentiation: Programming cells for responses in time and space. Semin Immunol. 2015;27:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva-Santos B, Pennington DJ, Hayday AC. Lymphotoxin-mediated regulation of gammadelta cell differentiation by alphabeta T cell progenitors. Science. 2005;307:925–928. doi: 10.1126/science.1103978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kannan Y, et al. IkappaBzeta augments IL-12- and IL-18-mediated IFN--gamma production in human NK cells. Blood. 2011;117:2855–2863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu X, et al. The gp49B1 inhibitory receptor regulates the IFN--gamma responses of T cells and NK cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:4095–4101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribot JC, et al. Cutting edge: adaptive versus innate receptor signals selectively control the pool sizes of murine IFN--gamma- or IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells upon infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:6421–6425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudin W, Favre N, Bordmann G, Ryffel B. Interferon-gamma is essential for the development of cerebral malaria. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:810–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chien YH, Meyer C, Bonneville M. gammadelta T cells: first line of defense and beyond. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:121–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes SM, Love PE. Distinct structure and signaling potential of the gamma delta TCR complex. Immunity. 2002;16:827–838. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayes SM, Love PE. Stoichiometry of the murine gammadelta T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2006;203:47–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegers GM, et al. Different composition of the human and the mouse gammadelta T cell receptor explains different phenotypes of CD3gamma and CD3delta immunodeficiencies. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2537–2544. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zapata DA, et al. Conformational and biochemical differences in the TCR.CD3 complex of CD8(+) versus CD4(+) mature lymphocytes revealed in the absence of CD3gamma. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35119–35128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Malave E, et al. Overlapping functions of human CD3delta and mouse CD3gamma in alphabeta T-cell development revealed in a humanized CD3gamma-mouse. Blood. 2006;108:3420–3427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayes SM, et al. Activation-induced modification in the CD3 complex of the gammadelta T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1355–1361. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin Y, et al. Cutting edge: Intrinsic programming of thymic gammadeltaT cells for specific peripheral tissue localization. J Immunol. 2010;185:7156–7160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roark CL, et al. Exacerbation of collagen-induced arthritis by oligoclonal, IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:5576–5583. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahtani-Patching J, et al. PreTCR and TCRgammadelta signal initiation in thymocyte progenitors does not require domains implicated in receptor oligomerization. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra47. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seiler MP, et al. Elevated and sustained expression of the transcription factors Egr1 and Egr2 controls NKT lineage differentiation in response to TCR signaling. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:264–271. doi: 10.1038/ni.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haks MC, Krimpenfort P, Borst J, Kruisbeek AM. The CD3gamma chain is essential for development of both the TCRalphabeta and TCRgammadelta lineages. EMBO J. 1998;17:1871–1882. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liehl P, et al. Host-cell sensors for Plasmodium activate innate immunity against liver-stage infection. Nat Med. 2014;20:47–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Team RA. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huber W, et al. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat Methods. 2015;12:115–121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.