Abstract

Deficiency of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF) has been associated with severe craniofacial anomalies in both humans and mice. Cranial neural crest cell (NCC)-derived VEGF regulates proliferation, vascularization and ossification of cartilage and membranous bone. However, the function of VEGF derived from specific subpopulations of NCCs in controlling unique aspects of craniofacial morphogenesis is not clear. In this study a conditional knockdown strategy was used to genetically delete Vegfa expression in Osterix (Osx) and collagen II (Col2)-expressing NCC descendants. No major defects in calvaria and mandibular morphogenesis were observed upon knockdown of VEGF in the Col2+ cell population. In contrast, loss of VEGF in Osx+ osteoblast progenitor cells led to reduced ossification of calvarial and mandibular bones without affecting the formation of cartilage templates in newborn mice. The early stages of ossification in the developing jaw revealed decreased initial mineralization levels and a reduced thickness of the collagen I (Col1)-positive bone template upon loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors. Increased numbers of proliferating cells were detected within the jaw mesenchyme of mutant embryos. Explant culture assays revealed that mandibular osteogenesis occurred independently of paracrine VEGF action and vascular development. Reduced VEGF expression in mandibles coincided with increased phospho-Smad1/5 (P-Smad1/5) levels and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (Bmp2) expression in the jaw mesenchyme. We conclude that VEGF derived from Osx+ osteoblast progenitor cells is required for optimal ossification of developing mandibular bones and modulates mechanisms controlling BMP-dependent specification and expansion of the jaw mesenchyme.

Keywords: VEGF, Craniofacial ossification, Bone development, Calvaria, Mandible, Osterix

1. Introduction

Developmental abnormalities in the growth of bones of the skull and face cause craniofacial defects such as unfused cranial sutures, mandibular hypoplasia, and cleft palate. Mechanisms underlying the etiology of such defects are incompletely understood and treatment options are limited. The craniofacial skeleton predominantly develops through intramembranous ossification involving NCC-derived progenitor cells [1–3]. The migration and differentiation of NCCs during morphogenesis of cartilage and membranous bone are tightly regulated by signals derived from various cell types.

VEGF is abundantly expressed by NCCs during craniofacial development [4]. Mice lacking the secreted isoform VEGF164 show craniofacial defects including cleft palate, unfused cranial sutures, and shorter jaws. Similar calvarial and mandibular malformations are observed upon conditional deletion of VEGF in NCCs [5,6]. Such defects were attributed to changes in VEGF-dependent proliferation, vascularization, and ossification during cartilage and bone formation. VEGF was also reported to regulate calvarial ossification [7] and maxillary and palatal mesenchyme [6] independent of vascular development. Furthermore, VEGF stimulates BMP2 expression prior to and during ossification of palatal shelves and maxilla, adding another layer of complexity to the function of VEGF during cartilage and membranous bone formation.

NCCs give rise to a variety of cell types and tissues during embryonic development, including cells that form the intramembranous bone, cartilage, and teeth [8,9]. Osteoblast progenitor cells and their progeny express the transcription factor Osx, which can also be detected in mesenchymal cells of the tooth germ but not in the epithelial tissue [10]. At embryonic day 15.5 (E15.5) abundant Osx expression is associated with bone formation while Meckel's cartilage lacks Osx expression. About 35% of the Osx+ precursors were previously reported to also be Col2 positive prior to becoming mature osteoblasts in developing dermal bones [11]. Furthermore, Col2-expressing cells are abundantly detected in the skull base, nasal region and Meckel's cartilage during craniofacial skeletal development [12]. At the initial stages of craniofacial ossification Vegfa expression was reported to be particularly high in the mesenchyme giving rise to the calvaria and mandible with low expression in the cartilage structures [5]. However, the contribution of VEGF derived from different subpopulations of NCCs, including Osx+ osteoblast progenitor cells and Col2+ cells, in the regulation of craniofacial skeletal development is not clear.

In this study, we show that VEGF derived from Osx+ osteoblast progenitor cells is required for optimal intramembranous bone formation in the developing jaw. The VEGF-dependent mechanisms appear to be independent of paracrine VEGF function and vascular development and likely involve the BMP-dependent specification and proliferation of cells within the jaw mesenchyme during mandibular osteogenesis.

2. Results

2.1. Osx- and Col2-expressing cells are distinct populations of VEGF-producing cells during cartilage and intramembranous bone formation

To assess the function of VEGF expressed by different subpopulations of NCCs, we first explored the presence of Osx-expressing osteoblast progenitor cells and Col2-expressing cells during craniofacial development. In situ hybridization on frontal sections of the heads of E14.5 and E16.5 wild-type (WT) (Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP) embryos showed expression of Osx and Col2 in distinct areas of developing calvaria and mandibles (Fig. 1A). Osx-expressing mesenchymal cells were detected surrounding the Col2+ Meckel's cartilage with a substantial number of mesenchymal cells co-expressing Osx and Col2. Such Col2+ osteoblastic progenitors were previously reported giving rise to about 35% of mature osteoblasts in developing mandibles [11]. Prior to generating mice with conditional loss of Vegfa alleles in Osx- and Col2-expressing cells we confirmed that the expression of Osx-Cre:GFP and Col2-Cre transgenes was similar to the endogenous Osx and Col2 expression profiles during craniofacial skeletal development (Fig. 1B). Indeed, the location of Osx/GFP-positive cells was overlapping with the endogenous Osx expression patterns in calvarial and mandibular areas of E14.5 and E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP embryos (Fig. 1B). Col2-expressing cells and their progeny, assessed by Col2-Cre-induced Tomato expression in craniofacial areas of E14.5 and E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Tomato; Col2-Cre embryos, were abundantly detected in cartilaginous structures as well as in mandibular and other craniofacial regions (Fig. 1B). Mesenchymal cells located in both developing mandible and calvaria showed significant levels of Vegfa expression as assessed by in situ hybridization on frontal sections of the heads of E14.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP embryos (Fig. 1C). In contrast, Vegfa expression appeared rather low in chondrocytes of the Meckel's cartilage. Conditional deletion of Vegfa in Osx+ precursors was confirmed by in situ hybridization on frontal sections of the heads of E14.5 Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Osx+ and Col2+ progenitor cell populations are located in developing cranial and mandibular regions. (A) The plane of section for which the images in A, B and C are shown is indicated with the dashed line. In situ hybridization on frontal head sections of Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mice at E14.5 (top) and E16.5 (bottom) for Osx (red) and Col2a1 (turquoise) (scale bars: 400 μm). To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of calvaria and mandible in images on left showing Osx and Col2a1 expression (scale bars: 200 μm). c, cartilage primordium of orbito-sphenoid bone; mk, Meckel's cartilage. (B) Analysis of different cell populations located in the head sections of E14.5 and E16.5 mice. Left: head sections from E14.5 (top) and E16.5 (bottom) Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mice indicating Osx/GFP+ cells. Right: head sections from E14.5 (top) and E16.5 (bottom) Vegfa+/+; Tomato; Col2-Cre mice showing cells derived from Col2+ osteochondroprogenitor cells (scale bar: 400 μm). (C) In situ hybridization on frontal head sections of E14.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice for Osx (red) and Vegfa (turquoise) (scale bars: 200 μm). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. VEGF stimulates intramembranous bone formation during craniofacial skeletal development

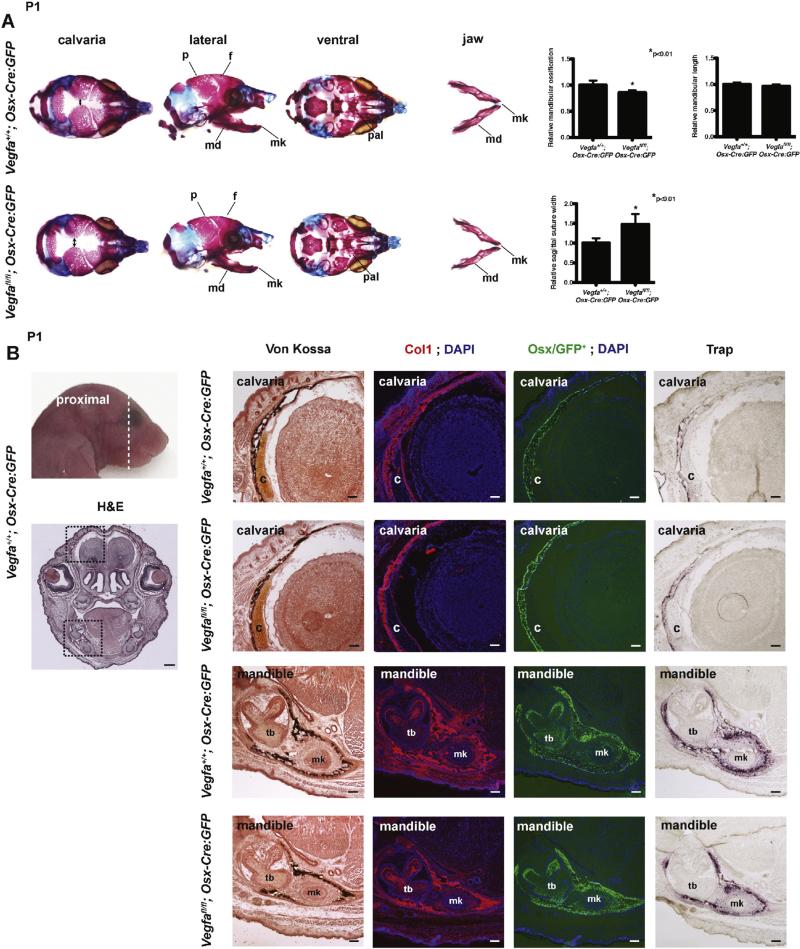

The skulls of newborn Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice were slightly smaller and showed significantly enlarged frontal fontanelle as assessed by measurement of the width of the sagittal suture compared with control Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mice (Fig. 2A). In addition, mandibular ossification was significantly reduced in mutant mice while jaw length and palatogenesis appeared unaffected (Fig. 2A). Histological analysis of frontal sections of the heads of Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice revealed thinner calvaria and mandibular structures as assessed by Von Kossa and anti-Col1 staining with fewer Trap-positive osteoclasts compared with control mice (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, loss of Vegfa in Col2+ cells led to no major ossification defects in newborn Vegfafl/fl; Col2-Cre mice (Fig. 3A, 3B) although the overall size of the skull and mandible appeared slightly reduced in a proportional manner compared to control Vegfa+/+; Col2-Cre mice (Fig. 3A). Von Kossa staining of frontal sections of the heads of Vegfafl/fl; Col2-Cre mice showed a reduced size of the cartilage primordium of orbito-sphenoid bone (Fig. 3B). As expected, the skeletal elements obtained from WT control mice carrying the Osx-Cre:GFP transgene (Fig. 2A) showed slightly diminished ossification compared to control mice carrying the Col2-Cre transgene (Fig. 3A) as Osx-Cre:GFP was previously reported to cause craniofacial bone development defects [13].

Fig. 2.

Osx+ osteoblast progenitor cell-derived VEGF regulates intramembranous ossification in developing craniofacial bones. (A) Whole-mount staining with Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue of skulls of P1 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice. Sagittal suture width indicated with double headed arrow. p, parietal bone; f, frontal bone; md, mandible; mk, Meckel's cartilage; pal, palatal bone. n = 9/8. Right graphs: Quantification of relative mandibular ossification (n = 8/8), relative mandibular length (n = 9/8), and relative width of sagittal suture (n = 6/6). Values represent mean values ± s.d. P < 0.01 for comparison between genotypes. (B) Top: The plane of section for which the images in B are shown is indicated with the dashed line. Bottom: Histological analysis of frontal head section of P1 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mice by H&E staining (scale bar: 400 μm). To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of calvaria and mandible in bottom image on left showing Von Kossa staining, anti-Col1 staining, Osx/GFP+ expression, and Trap staining of P1 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice (scale bar: 200 μm). c, cartilage primordium of orbito-sphenoid bone; tb, tooth bud; mk, Meckel's cartilage.

Fig. 3.

VEGF derived from Col2+ cells does not contribute to mineralization in developing craniofacial bones. (A) Whole-mount staining with Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue of skulls of P1 Vegfa+/+; Col2-Cre (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Col2-Cre (bottom) mice. Sagittal suture width indicated with double headed arrow. p, parietal bone; f, frontal bone; md, mandible; mk, Meckel's cartilage; pal, palatal bone. n = 9/9. Right graphs: quantification of relative mandibular ossification (n = 5/8) and relative mandibular length (n = 5/8). Values represent mean values ± s.d. (B) Von Kossa staining of frontal head sections of calvaria and mandibles of P1 Vegfa+/+; Col2-Cre (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Col2-Cre (bottom) mice (scale bar: 200 μm). c, cartilage primordium of orbito-sphenoid bone; tb, tooth bud; mk, Meckel's cartilage.

2.3. VEGF derived from Osx-expressing cells enhances initial mandible ossification independent of vascular development

To address the underlying mechanisms by which VEGF derived from Osx+ precursors regulates membranous bone formation, we focused on early jaw morphogenesis. Recent reports highlighted a role for NCC-derived VEGF in embryonic jaw extension [5] and palatogenesis [6]. At E14.5 the Meckel's cartilage has gained its mature shape while osteogenesis of the mandible is in the initial stages [5]. Although the length of the Meckel's cartilage appeared unaffected in E15.5 Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice, mandibular ossification was already reduced compared with littermate Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP controls (Fig. 4A). In situ hybridization on frontal sections of the heads of E16.5 embryos showed that the ratio of mesenchymal cells expressing Osx and Col2 was not affected in Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice (Fig. 4B). Additional histological analysis of frontal sections of E16.5 heads indicated that Osx/GFP expression and Col1-stained areas outlining mandibular thickness was reduced in mutant Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP compared with control embryos (Fig. 4B). Apoptosis of Osx+ precursors as assessed by TUNEL staining was not affected in developing mandibles of E16.5 Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP embryos (Fig. 5A). However, anti-Ki67 staining revealed increased numbers of proliferating cells within the jaw mesenchyme of mutant embryos (2.45 ± 1.38 times compared to controls) (Fig. 5B). Since NCC-derived VEGF was previously reported to regulate the growth of the mandibular artery leading to extension of the Meckel's cartilage [5], we assessed to what extent VEGF derived from Osx+ precursors affected vascularization of developing mandibles. Anti-CD31 staining indicated that the mandibular artery and the presence of blood vessels within the jaw mesenchyme were not affected in E16.5 Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP embryos (Fig. 5C), indicating that defective intramembranous bone formation upon loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors is largely independent of vascular development.

Fig. 4.

Reduced initial ossification and thickness of the mandibular template upon loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors. (A) Whole-mount staining with Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue of skulls of E15.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice. md, mandible; mk, Meckel's cartilage. To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of mandible in images on left. (B) Left: In situ hybridization on frontal head sections of Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice at E16.5 for Osx (red) and Col2a1 (turquoise) (scale bars: 200 μm). To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of mandible in images on left showing Osx and Col2a1 expression (scale bars: 50 μm). Middle: mandibular sections from E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice indicating Osx/GFP+ cells (scale bars: 200 μm). Mandibular thickness indicated with double headed arrow. Right: Anti-Col1 staining of mandibular sections from E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice (scale bars: 200 μm). tb, tooth bud; mk, Meckel's cartilage. Right graph: quantification of relative mandibular thickness. Values represent mean values ± s.d. P < 0.01 for comparison between genotypes. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

Loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors leads to increased cell proliferation without affecting vascular development within jaw mesenchyme. (A) TUNEL staining of mandibular sections from E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice (scale bars: 200 μm). (B) Anti-Ki67 staining of mandibular sections from E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice indicating proliferating cells in tooth bud (left) and jaw mesenchyme (middle) (scale bars: 200 μm). To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of jaw mesenchyme in images on left showing proliferating cells (scale bars: 50 μm). (C) Left: Anti-CD31 staining of mandibular section from E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mouse showing Osx/GFP+ cells (scale bar: 200 μm). tb, tooth bud; v, mandibular artery; mk, Meckel's cartilage. Right: magnified views of delineated area of mandible in image on left showing mandibular artery of E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice (scale bar: 200 μm). Arrows indicate CD31 expression in the mandibular artery and blood vessels, asterisk marks blood cells.

2.4. VEGF-dependent mandibular ossification is not mediated by paracrine VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling in Osx+ precursors

VEGF was previously reported to stimulate intramembranous ossification during calvarial explant culture in vitro [7]. To assess whether mandibular osteogenesis is regulated by paracrine VEGF signaling, we performed explant cultures with mandibles obtained from E15.5 WT mice (Fig. 6Aa). Dissected mandibles were grown in the presence of 10 ng/ml VEGF164 for 7 days followed by analysis of their ossification levels compared to untreated controls (Fig. 6Ab). A substantial increase in the Alizarin Red-stained areas surrounding the Alcian Blue-positive Meckel's cartilage was detected in both VEGF treated and control mandibles (Fig. 6Ab). However, VEGF treatment had no significant effect on the ossification levels (Fig. 6Ac), suggesting that paracrine VEGF function did not regulate mandibular bone formation. To further address the role of paracrine VEGF signaling in Osx+ precursors we assessed the expression of the major VEGF receptor involved in VEGF signaling, VEGFR2. In situ hybridization indicated that mRNA levels for VEGFR2 were detected in the vascular endothelium but at rather low levels in cells of the jaw mesenchyme of E14.5 and E16.5 Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP embryos (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, loss of VEGFR2 in Osx+ precursors did not result in obvious skeletal defects in newborn Vegfr2fl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP mice compared to control Vegfr2+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mice (Fig. 6C). To confirm that mandibular ossification is not regulated by paracrine VEGF signaling we used adenoviral Cre recombinase to knockdown VEGF in dissected mandibles obtained from E15.5 Vegfafl/fl mice (Fig. 7Aa). VEGF expression was reduced about 40% in protein lysates obtained from adenoviral Cre-treated mandibles compared to the adenoviral GFP-infected control (data not shown). Western blotting of mandibular protein lysates showed robust GFP expression in control mandibles infected with adenoviral GFP and reduced Col1 expression was detected upon VEGF knockdown (Fig. 7Ab). Treatment of mandibles with VEGF164 did not affect intramembranous ossification during mandibular explant culture (Fig. 7Ac). However, the relative levels of mandibular ossification were reduced about 34% compared with controls upon VEGF knockdown (data not shown); this roughly correlates with a 40% decrease in VEGF protein levels. We then addressed the possibility that VEGF-dependent control of intramembranous bone formation involves the regulation of additional signaling pathways. The timing of bone differentiation in mandibular mesenchyme is regulated by BMP signaling pathways [14–16] and VEGF was previously reported to stimulate the expression of BMP2 in NCCs [6]. Furthermore, Wnt/β-catenin is required for craniofacial development [17] while Ihh and PTHrP have been identified as negative regulators of osteoblast differentiation during dermal bone formation [11]. Western blotting of mandibular protein lysates upon knockdown of VEGF in jaw mesenchyme revealed increased levels of the downstream BMP mediators P-Smad1/5 while no major differences in the expression of β-catenin or Ihh proteins were detected (Fig. 7Ad). Furthermore, in situ hybridization on frontal sections of heads of E14.5 Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP embryos indicated that loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors resulted in increased Bmp2 expression within jaw mesenchyme during mandibular osteogenesis (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 6.

Mandibular ossification is not stimulated by paracrine VEGF signaling and loss of VEGFR2 in Osx+ precursors does not affect intramembranous bone formation. (A) a. Overview of mandibular dissection procedure on E15.5 embryos. b. Schematic overview of the experimental procedures of the mandibular explant culture. c. Quantification of relative mandibular ossification (n = 5/5). Values represent mean values ± s.d. (B) In situ hybridization on frontal head sections of Vegfr2 +/+; Osx-Cre:GFP mice at E14.5 (top) and E16.5 (bottom) for Osx (red) and Vegfr2 (turquoise) (scale bars: 400 μm). To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of mandible in images on left showing Osx and Vegfr2 expression (scale bars: 200 μm). mk, Meckel's cartilage. (C) Whole-mount Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue-stained skeletal preparations of P1 Vegfr2+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfr2fl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice. md, mandible; mk, Meckel's cartilage. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 7.

Reduced VEGF expression coincides with increased BMP signaling within jaw mesenchyme. (A) a. Schematic overview of the experimental procedures of the mandibular explant culture upon knockdown of VEGF. b. Western blotting of GFP and Col1 in whole mandibular lysates from Vegfafl/fl embryos treated with adenoviral Cre compared to adenoviral GFP (control). β-actin is loading control. c. Quantification of relative mandibular ossification (n = 3/3). Values represent mean values ± s.d. d. Western blotting of Ihh, β-catenin, and P-Smad1/5 in whole mandibular lysates from Vegfafl/fl embryos treated with adenoviral Cre compared to adenoviral GFP (control). HSP90 and β-actin are loading control. (B) In situ hybridization on frontal head sections of Vegfa+/+; Osx-Cre:GFP (top) and Vegfafl/fl; Osx-Cre:GFP (bottom) mice at E14.5 for Osx (red) and Bmp2 (turquoise) (scale bars: 200 μm). To the right are magnified views of delineated areas of jaw mesenchyme in images on left showing Osx and Bmp2 expression (scale bars: 100 μm). mk, Meckel's cartilage. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3. Discussion

Craniofacial anomalies arise from developmental defects in the formation of calvarial and mandibular bones. Elucidating the mechanisms of chondrogenesis and osteogenesis during craniofacial skeletal development is essential in order to enable innovation in therapeutic strategies for treatment of such craniofacial disorders. We have shown here that VEGF derived from the Osx+ osteoblast progenitor cell population is required for jaw mesenchyme to promote intramembranous bone formation.

VEGF is abundantly expressed by NCCs and plays multiple roles in regulating complex morphogenetic events during craniofacial skeletal development [5,6]. Not surprisingly, mouse models in which VEGF is specifically deleted in NCCs show dramatic craniofacial phenotypes, including bone hypoplasia of the cranium and mandible, cleft lip and palate, reduced ossification of the premaxillary and frontal bones, and changes in size and shape of the Meckel's cartilage resulting in shorter and misshapen mandibles. Defects upon loss of VEGF in NCCs arise at a developmental point after NCC specification and migration into the mandibular primordium (pharyngeal arch 1) and the anomalies were mainly attributed to inadequate vessel growth and arterial instability in the jaw [5]. To elucidate the role of VEGF derived from specific subpopulations of NCCs during craniofacial skeletal development, we conditionally deleted VEGF in Osx+ or Col2+ NCC descendants. Remarkably, loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors but not in the more abundant Col2-expressing cell population resulted in mild defects in the formation of craniofacial skeletal elements independent of vascular development. The lack of a phenotype upon deletion of VEGF using the Col2-Cre transgene in our studies was rather unexpected. We found that lineage tracing of Col2+ cells using the Tomato Cre reporter transgene indicated abundant Col2+ cells and their progeny at different stages during craniofacial skeletal development. Limited VEGF expression in these cells or, alternatively, suboptimal activity of Cre recombinase in Col2-expressing cells resulting in a partial knockdown of VEGF expression may explain the apparently normal development of the craniofacial elements upon conditional deletion of VEGF using the Col2-Cre transgene.

Our data suggest that VEGF may function in an autocrine manner in Osx+ precursors as it regulates the specification and expansion of mesenchymal cells in the jaw. Such a role for VEGF is supported by the results obtained from the explant culture assays, which revealed that paracrine VEGF did not affect mandibular osteogenesis in vitro (Fig. 8). Furthermore, loss of VEGFR2 in Osx+ precursors resulted in no major defects in craniofacial skeletal development. In contrast, paracrine VEGF was previously reported to increase osteoblast activity during calvarial growth in vitro [7]. Although both calvarial and mandibular bones develop as a result of intramembranous ossification, the mechanisms involved may vary amongst the individual membranous skeletal elements [18]. We propose that paracrine VEGF signaling is indispensable for craniofacial skeletogenesis mediated by vascular development, including regulation of the growth of the mandibular artery followed by embryonic jaw extension (Fig. 8) [5].

Fig. 8.

Model summarizing the paracrine and autocrine actions of VEGF in the jaw mesenchyme.VEGF produced by Osx+ osteoblast progenitors stimulates mandibular ossification in an autocrine manner. In contrast, NCC-derived VEGF enhances vascular development via paracrine signaling, thereby regulating jaw extension and osteogenesis.

The VEGF-dependent control of mandibular osteogenesis likely involves mechanisms at the stage of preosteoblast specification and expansion. Loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors but not in Col2+ osteochondroprogenitors was characterized by increased cell proliferation within the jaw mesenchyme. The thickness of the differentiating mandibular template was reduced but the ratio between Osx+ precursors and Col2+ osteochondroprogenitors appeared unaffected. Since the initial specification of NCCs into chondrocytes and preosteoblasts is primarily controlled by BMP signaling, we addressed the possibility that loss of VEGF in Osx+ precursors could modulate this pathway. The levels of downstream mediators P-Smad1/5 were increased upon reduction of VEGF levels in jaw mesenchyme and levels of Bmp2 expression appeared to be increased as well. In conclusion, VEGF derived from Osx+ precursors located in the jaw mesenchyme is required for optimal intramembranous bone formation. We propose that VEGF regulates osteogenesis in an autocrine manner independent of paracrine VEGF function and vascular development. The mechanisms of VEGF action likely involve the BMP-dependent specification and proliferation of cells within the jaw mesenchyme during craniofacial skeletal development.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Mouse strains

Floxed Vegfa and Vegfr2 (Flk1) mice used in this study were generated at Genentech. B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Osx-Cre:GFP [19] mice and Col2-Cre [20] mice have been described previously. Embryos were collected from timed pregnancies, and E0.5 was defined as the day that the male was separated from the female after the overnight mating. Genomic DNA, isolated using standard protocols from portions of mouse tails, was used for genotyping. All primers are listed below. All animal experiments were performed with protocols approved by Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals in accordance with U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

4.2. Primer sequences used for genotyping

| Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic-Cre | 5′-GATGAGGTTCGCAAGAACCTG-3′ | 5′-TGAACGAACCTGGTCGAAATC-3′ | ~350 bp |

| VEGFA | 5′-CCTGGCCCTCAAGTACACCTT-3′ | 5′-TCCGTACGACGCATTTCTAG-3′ | ~150 bp |

| VEGFR2 | 5′-GACTTGGTTCATCAGGCTAG-3′ | 5′-GACGCTGTTAAGCTGCTACAC-3′ | ~230 bp |

| Rosa wildtype | 5′-AAGGGAGCTGCAGTGGAGTA-3′ | 5′-CCGAAAATCTGTGGGAAGTC-3′ | ~297 bp |

| Rosa Tomato mutant | 5′-CTGTTCCTGTACGGCATGG-3′ | 5′-GGCATTAAAGCAGCGTATCC-3′ | ~169 bp |

4.3. Skeletal preparations and quantification of mandibular ossification, mandibular length, width of sagittal suture, and mandibular thickness

Bones and cartilage in heads of E15.5 and newborn mice (P1) were visualized by Alizarin Red S and Alcian Blue (Sigma-Aldrich) staining. Skeletal samples were cleared in potassium hydroxide (1%)/glycerol (20%) solution, and stored and photographed in glycerol.

Mandibular ossification, mandibular length, and width of sagittal suture were measured in images of whole mount mandibles and calvaria obtained from newborn mice using ImageJ program. Mandibular ossification was determined as the area of positive Alizarin Red staining in the mandible, mandibular length was defined as the linear distance between the anterior end and posterior end of the mandible. The minimal distance between the parietal bones represents the width of the sagittal suture. Mandibular thickness was measured in mandibular sections of E16.5 embryos using ImageJ program. Seven central-cut sections were analyzed per bone. Mandibular thickness was defined as the distance of the mandibular template across the center of the Meckel's cartilage. All the measurements are presented as relative values of control measurements.

4.4. Histology

For histological analysis, heads of embryos and newborn mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C overnight, infiltrated with a series of sucrose and embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek®) compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA) for cryostat sectioning. Frozen sections (7.5 μm) were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Von Kossa staining and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (Trap) staining as previously described [21]. Photographs of histological sections were taken with a Nikon 80i Upright microscope using NIS-Elements AR3.1 software.

4.5. Double-labeling RNA in situ hybridization

Double-labeling RNA in situ hybridization was performed on frozen sections of heads using the RNAscope 2-plex Detection Kit (Chromogenic) as described in manufacturer's instructions (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). RNAscope probes used include: Sp7 (NM_130458.3, region 837-2230), which was detected using the Fast Red detection reagent, and Col2a1 (NM_001113515.2, region 729-2036), Vegfa (NM_001025257.3, region 946-2156), Kdr (Vegfr2) (NM_010612.2, region 1766-2673) and Bmp2 (NM_007553.3, region 872-2039), which were detected using the Green detection reagent.

4.6. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

For IHC, frozen sections of heads were stained with Collagen I (1:100; ab21286; Abcam), Ki67 (1:500; ab16667; Abcam) and CD31 (1:100; ab28364; Abcam) primary antibodies and Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen), according to Cell Signaling Technology protocols. Control sections incubated with control rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) did not show any staining. All sections were mounted with HardSet Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Labs), and photographed using a Nikon 80i Upright microscope using MetaMorph Software.

4.7. Quantification of Ki67 staining

The number of proliferating cells, stained by Ki67 antibody, was counted in six defined (140 × 140 μm) regions within the jaw mesenchyme of the mandibular sections of E16.5 embryos using ImageJ program. Three central-cut sections at least 22.5 μm apart were analyzed per bone.

4.8. TUNEL staining

Apoptotic cells were detected on frozen sections of heads by using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR Red (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.9. Mandibular explant culture

Mandibles of E15.5 wild-type (WT) embryos were dissected in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured in osteogenic medium containing β-glycerophosphate (8 mM; Sigma-Aldrich) and l-ascorbic acid phosphate (50 μg/ml; Wako), or in osteogenic medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml of VEGF164. Medium was replaced twice during the culture period. The mandibles were harvested on day 7 and subjected to Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue staining. Mandibular ossification was analyzed and quantified as described above. The entire experiment was repeated once and consisted of a total of 10 control and 10 VEGF164 treated mandibles.

Mandibles of E15.5 Vegfafl/fl embryos were dissected in HBSS and infected with either Ad-Cre or Ad-GFP (Vector Biolabs) for 24 h followed by culture in osteogenic medium. Protein was harvested from mandibles after 4 day culture for VEGF ELISA and Western Blotting analysis. Additional mandibles were infected with Ad-Cre and cultured in osteogenic medium (n = 3) or in osteogenic medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml of VEGF164 (n = 3). After 7 days of culture, the mandibles were subjected to Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue staining, and mandibular ossification was analyzed.

4.10. ELISA assays

VEGF protein levels in mandibular lysates were assessed using the Quantikine Mouse VEGF Immunoassay (R&D Systems) in accordance with manufacturer's instructions.

4.11. Western blotting

Protein lysates of mandibles from mandibular explant culture were prepared and subjected to Western Blotting as described [21]. Primary antibodies used include: GFP (1:1000; ab290; Abcam), Collagen I (1:1000; ab21286; Abcam), Ihh (1:1000; ab39634; Abcam), β-catenin (1:1000; 9587; Cell Signaling), P-Smad1/5 (1:1000; 9516; Cell Signaling), HSP90 (1:1000; sc-13,119; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (1:5000; A5441; Sigma-Aldrich).

4.12. Statistical analysis

Results were presented as mean ± s.d. and unpaired student's t tests were used. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yulia Pittel for secretarial assistance and Sofiya Plotkina for technical support. We thank Napoleone Ferrara (UC San Diego) and Genentech Inc. for providing mice with floxed Vegfa and Vegfr2 (Flk1) alleles and Beate Lanske (HSDM) for providing Col2-Cre mice. We acknowledge services of Nikon Imaging Center at HMS.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants AR36819, AR36820, and AR48564 (to B.R. Olsen).

Abbreviations used

- NCC

neural crest cell

- Osx

Osterix

- Col2

collagen II

- Col1

collagen I

Footnotes

Author contributions

X.D, S.B., B.R.O and A.D.B designed experiments and interpreted results. X.D, S.B., and A.D.B performed the experiments. X.D, B.R.O and A.D.B wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bronner ME, LeDouarin NM. Development and evolution of the neural crest: an overview. Dev. Biol. 2012;366:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chai Y, Maxson RE., Jr. Recent advances in craniofacial morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:2353–2375. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weston JA, Thiery JP. Pentimento: neural crest and the origin of mesectoderm. Dev. Biol. 2015;401:37–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stalmans I, Lambrechts D, De Smet F, Jansen S, Wang J, Maity S, Kneer P, von der Ohe M, Swillen A, Maes C, Gewillig M, Molin DG, Hellings P, Boetel T, Haardt M, Compernolle V, Dewerchin M, Plaisance S, Vlietinck R, Emanuel B, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Scambler P, Morrow B, Driscol DA, Moons L, Esguerra CV, Carmeliet G, Behn-Krappa A, Devriendt K, Collen D, Conway SJ, Carmeliet P. VEGF: a modifier of the del22q11 (DiGeorge) syndrome? Nat. Med. 2003;9:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nm819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiszniak S, Mackenzie FE, Anderson P, Kabbara S, Ruhrberg C, Schwarz Q. Neural crest-derived VEGF promotes embryonic jaw extension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:6086–6091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419368112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill C, Jacobs B, Kennedy L, Rohde S, Zhou B, Baldwin S, Goudy S. Cranial neural crest deletion of VEGFa causes cleft palate with aberrant vascular and bone development. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;361:711–722. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelzer E, McLean W, Ng YS, Fukai N, Reginato AM, Lovejoy S, D'Amore PA, Olsen BR. Skeletal defects in VEGF(120/120) mice reveal multiple roles for VEGF in skeletogenesis. Development. 2002;129:1893–1904. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creuzet S, Couly G, Le Douarin NM. Patterning the neural crest derivatives during development of the vertebrate head: insights from avian studies. J. Anat. 2005;207:447–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noden DM, Trainor PA. Relations and interactions between cranial mesoderm and neural crest populations. J. Anat. 2005;207:575–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abzhanov A, Rodda SJ, McMahon AP, Tabin CJ. Regulation of skeletogenic differentiation in cranial dermal bone. Development. 2007;134:3133–3144. doi: 10.1242/dev.002709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori-Akiyama Y, Akiyama H, Rowitch DH, de Crombrugghe B. Sox9 is required for determination of the chondrogenic cell lineage in the cranial neural crest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:9360–9365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1631288100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Mishina Y, Liu F. Osterix-Cre transgene causes craniofacial bone development defect. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2015;96:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9945-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Selever J, Murali D, Sun X, Brugger SM, Ma L, Schwartz RJ, Maxson R, Furuta Y, Martin JF. Threshold-specific requirements for Bmp4 in mandibular development. Dev. Biol. 2005;283:282–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merrill AE, Eames BF, Weston SJ, Heath T, Schneider RA. Mesenchyme-dependent BMP signaling directs the timing of mandibular osteogenesis. Development. 2008;135:1223–1234. doi: 10.1242/dev.015933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonilla-Claudio M, Wang J, Bai Y, Klysik E, Selever J, Martin JF. Bmp signaling regulates a dose-dependent transcriptional program to control facial skeletal development. Development. 2012;139:709–719. doi: 10.1242/dev.073197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brault V, Moore R, Kutsch S, Ishibashi M, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP, Sommer L, Boussadia O, Kemler R. Inactivation of the beta-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development. 2001;128:1253–1264. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helms JA, Schneider RA. Cranial skeletal biology. Nature. 2003;423:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nature01656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133:3231–3244. doi: 10.1242/dev.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long F, Zhang XM, Karp S, Yang Y, McMahon AP. Genetic manipulation of hedgehog signaling in the endochondral skeleton reveals a direct role in the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation. Development. 2001;128:5099–5108. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan X, Murata Y, Liu Y, Nicolae C, Olsen BR, Berendsen AD. Vegfa regulates perichondrial vascularity and osteoblast differentiation in bone development. Development. 2015;142:1984–1991. doi: 10.1242/dev.117952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]