Abstract

Introduction

Although population studies have documented the poorer health outcomes of sexual minorities, few have taken an intersectionality approach to examine how sexual orientation, gender, and race jointly affect these outcomes. Moreover, little is known about how behavioral risks and healthcare access contribute to health disparities by sexual, gender, and racial identities.

Methods

Using ordered and binary logistic regression models in 2015, data from the 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Surveys (N=62,302) were analyzed to study disparities in self-rated health and functional limitation. This study examined how gender and race interact with sexual identity to create health disparities, and how these disparities are attributable to differential exposure to behavioral risks and access to care.

Results

Conditional on sociodemographic factors, all sexual–gender–racial minority groups except straight white women, gay white men, and bisexual non-white men reported worse self-rated health than straight white men (p<0.05). Some of these gaps were attributable to differences in behaviors and healthcare access. All female groups, as well as gay non-white men, were more likely to report a functional limitation than straight white men (p<0.05), and these gaps largely remained when behavioral risks and access to care were accounted for. The study also discusses health disparities within sexual–gender–racial minority groups.

Conclusions

Sexual, gender, and racial identities interact with one another in a complex way to affect health experiences. Efforts to improve sexual minority health should consider heterogeneity in health risks and health outcomes among sexual minorities.

Introduction

Many studies indicate that sexual minorities have poorer health outcomes, including self-rated health (SRH), cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, functional limitations, and lifetime mood and anxiety disorders, relative to heterosexuals.1–5 Sexual minorities are also more likely to exhibit health risks, such as smoking, heavy drinking, obesity (particularly among sexual minority women), and limited access to healthcare services.1,6–12 However, few studies have examined how gender and race/ethnicity may jointly interact with sexual orientation to affect health and exposure to health risks. Although recent population-level surveys have increasingly shown that some disparities in health risks by sexual identity—including obesity, drinking, and insurance coverage—are more pronounced among women than men,1,10,13 research on the intersection effects of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation on health is still limited in quantity and scope. Some research hypothesizes that sexual minorities of color may be exposed to greater stress and health risks than their white counterparts due to higher levels of heterosexism in their communities, but empirical evidence, mostly based on small samples, remains inconsistent.14–16 Other work suggests that sexual minorities of color are more resilient in the face of heterosexism because they have developed skills/strategies to cope with racism.16–18 However, whether their health outcomes also reflect such resilience remains an open question.

The present study aims to fill this gap by comparing health status, behavioral risks, and access to health care across 12 sexual–gender–racial identity groups (including white and non-white straight/gay/bisexual men and women). Recognizing that few studies have investigated the link between health outcomes and risk factors across these groups,19 the study also examines how behavioral risks and healthcare access contribute to observed health disparities. Building on the approach of intersectionality,20–27 this study tests whether individuals with multiple disadvantages in their social position (in terms of sexual orientation, gender, and race) experience much poorer health than their privileged or singly disadvantaged counterparts. Notably, intersectionality is not an additive approach and does not privilege any single dimension of inequality. Instead, it emphasizes the configurations of social identities that produce unique advantages and disadvantages for health and well-being.20,24,26 Therefore, sexual minority women of color, for example, may not exhibit the poorest health outcomes as might be expected. Rather, as the resilience perspective posits, strengths and strategies developed to cope with sexism, racism, or heterosexism may buffer the harmful consequences of one another. Using a nationally representative sample, this paper is one of the few studies incorporating intersectionality into population health research.21,24

Methods

Study Sample

The study used pooled data from the 2013–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), collected by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NHIS is a household survey conducted annually since 1957, with questions on sexual orientation first asked in 2013. The NHIS covers a broad range of health topics, including health status and limitation of activity, health behaviors, and healthcare access and utilization. The survey generates representative samples of the civilian, non-institutionalized population residing in the U.S. using multistage sampling techniques. The 2013 and 2014 surveys were conducted through face-to-face interviews in respondents’ homes using computer-assisted personal interviewing. The household response rates were 75.7% in 2013 and 73.8% in 2014.

Because the sexual orientation question is included only in the Sample Adult component of the NHIS, the current study focused on adults aged ≥18 years. The sexual orientation question asked sample adults: Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself? (1) Gay or lesbian; (2) Straight, that is, not gay or lesbian; (3) Bisexual; (4) Something else; and (5) I don’t know the answer. Of the 69,270 adults who answered the question (97% of the original sample), 67,152 (96.9%) self-identified as straight, 1,149 (1.7%) as gay or lesbian, and 515 (0.7%) as bisexual. In addition, 144 (0.2%) individuals responded Something else, and 310 (0.4%) individuals responded I don’t know the answer. National Center for Health Statistics suggests that there is minimal classification error according to the quality assessment of sexual orientation data using follow-up questions that target people in the Something else or I don’t know the answer categories.28 This study focused on the comparison of the self-identified straight, gay/lesbian, and bisexual groups and excluded the two ambiguous groups from the analysis. Respondents were also asked about their gender identity (male or female) and racial/ethnic identity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, or others). Because each racial/ethnic minority group has a small number of sexual minority cases (particularly among Asian and others), blacks and Hispanics were grouped into a single non-white category and Asians and other races were excluded from the analysis. This study also excluded 2,518 records containing missing values for one or more of the health outcome, behavioral risk (except the BMI), healthcare access, or sociodemographic variables. Because the BMI contained a larger number of missing records (n=1,613), multiple imputation based on sociodemographic characteristics was carried out for this variable (Appendix S1). All analyses and results that are reported are based on the imputed data set. The final analytic sample included 62,302 individuals; sample sizes for each of the 12 sexual–gender–racial groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2013–2014 Pooled National Health Interview Survey Samples, by Gender, Race, and Sexual Identity

| White male | Non-white male | White female | Non-white female | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | L/G | B | S | L/G | B | S | L/G | B | S | L/G | B | |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||||||

| Mean age | 48 | 44 | 43 | 41 | 38 | 38 | 50 | 44 | 33 | 43 | 39 | 31 |

| % No high school diploma | 9 | 5 | 6 | 26 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 5 | 19 | 26 | 9 | 17 |

| % High school diploma | 26 | 17 | 14 | 31 | 21 | 11 | 25 | 17 | 15 | 26 | 30 | 43 |

| % Some college | 30 | 32 | 38 | 28 | 43 | 48 | 33 | 36 | 33 | 32 | 38 | 26 |

| % Bachelor’s degree | 34 | 46 | 42 | 15 | 27 | 21 | 33 | 42 | 32 | 16 | 23 | 14 |

| % Married or living with partner | 67 | 45 | 32 | 59 | 28 | 11 | 62 | 62 | 38 | 48 | 42 | 26 |

| % Hispanic | -- | -- | -- | 57 | 50 | 49 | -- | -- | -- | 52 | 48 | 40 |

| % Foreign born | 6 | 2 | 1 | 37 | 19 | 21 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 33 | 23 | 12 |

| Health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| % SRH less than very | ||||||||||||

| good | 36 | 34 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 39 | 37 | 39 | 39 | 47 | 49 | 39 |

| % Functional limitation | 32 | 30 | 37 | 23 | 31 | 26 | 42 | 43 | 41 | 34 | 38 | 37 |

| Health behaviors/indicators | ||||||||||||

| % Heavy/moderate drinker | 32 | 39 | 52 | 22 | 31 | 25 | 17 | 24 | 27 | 7 | 13 | 17 |

| % BMI >30 | 30 | 25 | 30 | 32 | 27 | 30 | 25 | 34 | 33 | 37 | 39 | 45 |

| % Currently smoke | 20 | 25 | 29 | 19 | 25 | 32 | 17 | 27 | 29 | 11 | 20 | 20 |

| % Exercise 4+ times weekly | 34 | 39 | 44 | 30 | 43 | 39 | 30 | 27 | 42 | 24 | 25 | 30 |

| % Have trouble sleeping | 47 | 51 | 69 | 36 | 55 | 48 | 58 | 58 | 71 | 46 | 55 | 62 |

| Healthcare access | ||||||||||||

| % No health insurance | 11 | 10 | 18 | 31 | 34 | 36 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 24 | 23 | 22 |

| % Medical care delayed due to cost | 8 | 11 | 26 | 10 | 17 | 27 | 10 | 20 | 22 | 12 | 21 | 20 |

| % Medical care unmet due to cost | 6 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 10 | 29 | 7 | 17 | 15 | 10 | 21 | 10 |

| % Can’t afford health services | 13 | 21 | 31 | 19 | 25 | 24 | 18 | 20 | 39 | 25 | 29 | 31 |

| % Save medication to save money | 17 | 19 | 31 | 15 | 16 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 39 | 21 | 21 | 24 |

| N | 18,174 | 400 | 101 | 8,796 | 175 | 40 | 21,828 | 306 | 225 | 11,963 | 181 | 113 |

S, Straight; L/G, Lesbian or Gay; B, Bisexual; SRH, Self-Rated Health

All proportions based on survey-adjusted sample weights. For educational attainment outcomes, numbers may not sum to one due to rounding. For BMI outcome, only non-imputed values are included.

Measures

Two health outcomes (dependent variables) were examined: SRH and functional limitation. SRH had five ordinal response categories: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Higher SRH values reflect poorer health. Functional limitation is an indicator of whether the respondent experiences any difficulty in activities that require sustained mobility, agility, dexterity, or social participation (Appendix S2 provides full definition).

Two sets of health risk factors were considered: health behaviors/indicators (smoking, drinking, obesity, exercise, and sleep problem) and healthcare access (ability to afford health expenditures). Smoking indicates whether or not the respondent currently smokes cigarettes. Drinking was measured by the status of lifetime alcohol consumption, with the following four response categories: lifetime abstainer, former drinker (no drinking in the past year), current infrequent/light drinker, and current moderate/heavy drinker (Appendix S3 provides definitions). Obesity was measured by BMI (weight (kg)/ height (m)2) in four standard categories: underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9), and obese (≥30). Exercise is an indicator of whether the respondent does vigorous leisure-time physical activity that causes heavy sweating and large increases in breathing/heart rate four or more times a week. Sleep problem indicates whether or not the respondent has trouble falling asleep or staying asleep in the past week.

Ability to afford health expenditures was evaluated using five variables. First, no health insurance indicates that the respondent is not covered by any kind of health insurance at the time of survey. Second, delayed medical care indicates whether the respondent ever delays medical care because of worry about the cost. Third, unmet need for medical care indicates whether there is any time when the respondent needed medical care but did not receive it because they could not afford it. Fourth, inability to afford specific health services indicates whether there is any time when the respondent needed any of the following health care but did not obtain it: prescription medicines, mental health care or counseling, dental care including check-ups, eyeglasses, seeing a specialist, and having follow-up care. Lastly, saving money for medication indicates whether the respondent does any of the following to save money: skipping medication doses, taking less medicine, delaying filling a prescription, asking a doctor for a lower cost medication, buying prescription drugs from another country, and using alternative therapies.

In all regression analyses, age, educational attainment, marital/cohabiting status, and Hispanic and foreign-born backgrounds were included as covariates.

Statistical Analysis

Ordered logistic regression models (for SRH) and binary logistic regression models (for functional limitation) were run to examine how disparities in the health outcomes by gender, race, and sexual identity are related to and explained by differences in exposure to health risks. Survey-adjusted tests—based on the F reference distribution described for testing coefficients from multiply imputed data—were used to determine whether the health disparity for a specific racial–gender–sexual minority is significantly reduced when controls for behavioral risk and access to health care are taken into account.29–32 All statistical analyses were adjusted to account for survey design, and conducted in 2015 using Stata, version 13.

Results

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the NHIS sample, by racial, gender, and sexual identity. Bisexuals were generally younger than straights/gays/lesbians of the same race and gender; this age difference was more pronounced among women. Sexual minorities tended to have higher (or at least comparable) levels of education than straights of the same race and gender, but non-white bisexual women exhibited lower education attainment. Sexual minorities were also less likely to be married or living with a partner, except that white lesbian women reported a similar rate of marriage/cohabitation as white straight women. Among non-white respondents, straights showed a higher percentage of being Hispanic. Further, straights were more likely to be foreign born, except among white women.

Several groups reported poorer SRH than others, including non-white straight and lesbian women. White women (regardless of sexual identity) were more likely to report a functional limitation. By contrast, non-white men were less likely to do so.

There were a few notable differences in health behaviors and access to care. White race, sexual minority status, and male gender were, respectively, related to higher rates of heavy/moderate drinking, with white bisexual men reporting the highest levels. Sexual minority women were more likely to be obese, especially among non-white lesbian/bisexual women. Overall, sexual minorities were more likely to smoke than straights of the same gender and race, but they exercised more often. Lastly, sexual minorities generally had more trouble sleeping, with white bisexual men and women showing the highest rates of sleeplessness.

Finally, though racial minority status appeared to be an important factor in having no insurance coverage, sexual minority status appeared more relevant to having delayed or unmet medical care because of cost, being unable to afford health services, and saving money for medication. The following analysis (adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics) compared health outcomes across groups.

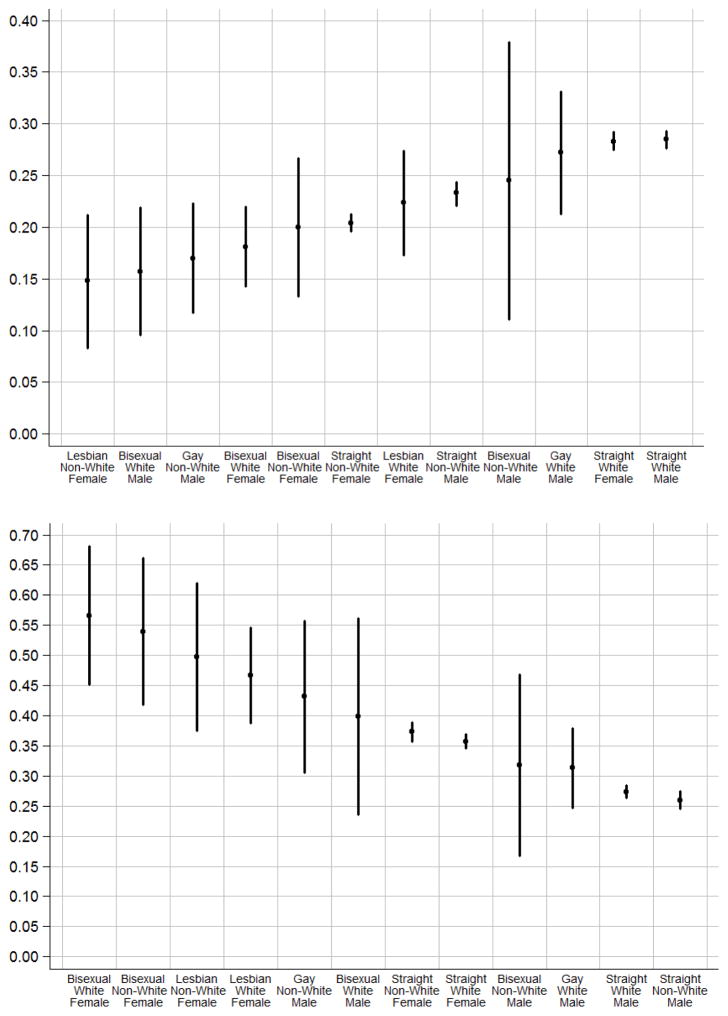

Table 2 shows that conditional on sociodemographic factors, all groups except white gay men, non-white bisexual men, and white straight women reported worse SRH than white straight men (p<0.05, Base Model). Among women, white bisexuals, non-white straights, and non-white gays reported poorer health than white straights. A similar pattern was observed among men. Further, among straights, non-white men and women reported poorer health than white men or women. However, among gays/lesbians or among bisexuals, no significant difference was found by race and gender. Lastly, among whites, bisexual men and women both exhibited disadvantaged health relative to their straight counterparts; no such evidence was found among non-whites. All of these differences were significant at the p<0.05 level. Figure 1A summarizes the predicted probabilities of reporting excellent health across all groups based on this model. In sum, although sexual minority, female, and non-white identities were generally associated with worse SRH, these disadvantages interacted in a complex way to affect health status. The findings supported the non-additive perspective of intersectionality.

Table 2.

Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis of Self Rated Health

| Base model | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Straight white male | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||

| Gay white male | 1.06 | (0.79, 1.43) | 1.07 | (0.81, 1.42) | 0.95 | (0.71, 1.28) | 0.99 | (0.75, 1.31) | ||||

| Bisexual white male | 2.13 | *** | (1.34, 3.37) | 2.00 | ** | (1.24, 3.23) | 1.62 | * | (1.00, 2.63) | 1.69 | * | (1.03, 2.76) |

| Straight non-white male | 1.31 | *** | (1.21, 1.42) | 1.27 | *** | (1.18, 1.38) | 1.30 | *** | (1.20, 1.41) | 1.25 | *** | (1.16, 1.36) |

| Gay non-white male | 1.95 | *** | (1.33, 2.85) | 1.81 | ** | (1.23, 2.66) | 1.78 | ** | (1.15, 2.75) | 1.71 | * | (1.11, 2.63) |

| Bisexual non-white male | 1.23 | (0.59, 2.53) | 1.04 | (0.53, 2.05) | 0.98 | (0.42, 2.24) | 0.88 | (0.42, 1.87) | ||||

| Straight white female | 1.01 | (0.96, 1.05) | 0.97 | (0.92, 1.02) | 0.93 | ** | (0.89, 0.98) | 0.92 | *** | (0.87, 0.96) | ||

| Lesbian white female | 1.38 | * | (1.03, 1.85) | 1.08 | (0.82, 1.41) | 1.16 | (0.86, 1.57) | 0.96 | (0.73, 1.27) | |||

| Bisexual white female | 1.80 | ** | (1.39, 2.33) | 1.50 | *** | (1.17, 1.92) | 1.32 | * | (1.02, 1.71) | 1.21 | (0.94, 1.55) | |

| Straight non-white female | 1.55 | *** | (1.45, 1.66) | 1.37 | *** | (1.28, 1.47) | 1.42 | *** | (1.33, 1.52) | 1.27 | *** | (1.18, 1.36) |

| Lesbian non-white female | 2.29 | ** | (1.37, 3.86) | 1.79 | * | (1.05, 3.05) | 1.90 | * | (1.11, 3.25) | 1.57 | (0.92, 2.68) | |

| Bisexual non-white female | 1.59 | * | (1.04, 2.43) | 1.24 | (0.77, 2.01) | 1.31 | (0.85, 2.00) | 1.08 | (0.67, 1.74) | |||

| Age | 1.03 | *** | (1.03, 1.03) | 1.03 | *** | (1.03, 1.03) | 1.03 | *** | (1.03, 1.03) | 1.03 | *** | (1.03, 1.03) |

| Less than high school | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||

| High school diploma | 0.60 | *** | (0.55, 0.64) | 0.63 | *** | (0.58, 0.67) | 0.62 | *** | (0.57, 0.67) | 0.64 | *** | (0.59, 0.69) |

| Some college | 0.47 | *** | (0.43, 0.50) | 0.52 | *** | (0.48, 0.56) | 0.47 | *** | (0.44, 0.51) | 0.52 | *** | (0.48, 0.56) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.24 | *** | (0.23, 0.26) | 0.33 | *** | (0.30, 0.35) | 0.27 | *** | (0.25, 0.29) | 0.34 | *** | (0.32, 0.37) |

| Married | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||

| Never married | 1.09 | ** | (1.03, 1.16) | 1.18 | *** | (1.12, 1.25) | 1.12 | *** | (1.05, 1.18) | 1.19 | *** | (1.12, 1.26) |

| Separated/divorced | 1.47 | *** | (1.39, 1.55) | 1.32 | *** | (1.25, 1.40) | 1.29 | *** | (1.22, 1.36) | 1.21 | *** | (1.14, 1.28) |

| Widowed | 0.93 | (0.86, 1.01) | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.05) | 0.96 | (0.88, 1.05) | 0.98 | (0.90, 1.07) | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.85 | *** | (0.79, 0.91) | 0.94 | (0.87, 1.02) | 0.87 | *** | (0.81, 0.94) | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.04) | ||

| Foreign born | 0.82 | *** | (0.76, 0.88) | 0.93 | (0.86, 1.01) | 0.84 | *** | (0.77, 0.91) | 0.93 | (0.86, 1.01) | ||

| Lifetime abstainer | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||||

| Former drinker | 1.42 | *** | (1.33, 1.53) | 1.35 | *** | (1.26, 1.44) | ||||||

| Light drinker | 0.90 | *** | (0.85, 0.96) | 0.87 | *** | (0.82, 0.92) | ||||||

| Moderate/heavy drinker | 0.75 | *** | (0.69, 0.80) | 0.73 | *** | (0.68, 0.78) | ||||||

| Underweight | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||||

| Normal weight | 0.68 | *** | (0.56, 0.82) | 0.69 | *** | (0.57, 0.83) | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.85 | (0.70, 1.02) | 0.86 | (0.71, 1.04) | ||||||||

| Obese | 1.58 | *** | (1.31, 1.90) | 1.56 | *** | (1.29, 1.87) | ||||||

| Current smoker | 2.00 | *** | (1.90, 2.11) | 1.84 | *** | (1.74, 1.94) | ||||||

| Exercise 4+ times weekly | 0.63 | *** | (0.60, 0.66) | 0.63 | *** | (0.60, 0.66) | ||||||

| Trouble sleeping | 1.77 | *** | (1.71, 1.85) | 1.56 | *** | (1.50, 1.63) | ||||||

| No health insurance | 0.83 | *** | (0.77, 0.88) | 0.82 | *** | (0.77, 0.88) | ||||||

| Delayed medical care | 1.43 | *** | (1.31, 1.55) | 1.37 | *** | (1.26, 1.49) | ||||||

| Unmet medical care | 1.47 | *** | (1.33, 1.62) | 1.43 | *** | (1.29, 1.57) | ||||||

| Can’t afford health services | 1.94 | *** | (1.82, 2.06) | 1.70 | *** | (1.59, 1.81) | ||||||

| Save medication | 1.52 | *** | (1.44, 1.61) | 1.38 | *** | (1.31, 1.46) | ||||||

| N | 62,302 | 62,302 | 62,302 | 62,302 | ||||||||

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Probability of reporting excellent self-rated health, conditional on sociodemographic characteristics, by gender, race, and sexual identity.

Note: Circles indicate point estimates. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1B. Probability of reporting any functional limitation, conditional on sociodemographic characteristics, by gender, race, and sexual identity.

Note: Circles indicate point estimates. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

The SRH gaps between groups were attributable to both health behaviors and access to health care. These results are presented in Models 2–4 in Table 2. The disparities between white straight men and white or non-white lesbian and bisexual women were no longer significant after differences in health behaviors and access to care were adjusted. By contrast, the lower SRH among white bisexual men, non-white gay men, and non-white straight men and women (as compared with white straight men), though partially reduced, remained significant after the risk factors were adjusted. Finally, between minority groups in any form (i.e., groups other than white straight men), gaps in SRH no longer existed once health behaviors and healthcare access were accounted for, with the exception of white straight women exhibiting better health.

Functional limitation showed a different pattern of disparities from SRH (Table 3). Conditional on sociodemographic factors, all female groups were more likely to report a functional limitation than white straight men (p<0.05, Base Model); among men, this was true only of non-white gay men. Among gays/lesbians and among straights, a gender difference was also prominent. Specifically, white lesbians were more likely to have a functional limitation than white gay men, and both white and non-white straight women reported poorer functional health than white or non-white straight men. Lastly, there were some differences by sexual identity among women. White lesbian and bisexual women both exhibited higher odds of having functional limitation than white straight women. Non-white bisexual women also showed higher odds than non-white straight women. All the above comparisons were significant at the p<0.05 level. Figure 1B displays the predicted probabilities of reporting any functional limitation based on this model. In sum, gender and sexual identities mattered for functional health, and sexual minority women reported the highest rates of functional limitation. By contrast, racial identity did not appear to play a significant role in shaping functional health.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Functional Limitation

| Base model | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Straight white male | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||

| Gay white male | 1.21 | (0.89, 1.65) | 1.22 | (0.91, 1.64) | 1.07 | (0.78, 1.46) | 1.13 | (0.83, 1.53) | ||||

| Bisexual white male | 1.76 | (0.89, 3.46) | 1.61 | (0.75, 3.46) | 1.30 | (0.67, 2.53) | 1.30 | (0.62, 2.75) | ||||

| Straight non-white male | 0.93 | (0.85, 1.02) | 0.92 | (0.83, 1.02) | 0.92 | (0.84, 1.02) | 0.90 | (0.82, 1.00) | ||||

| Gay non-white male | 2.01 | ** | (1.21, 3.35) | 1.85 | * | (1.14, 2.99) | 1.93 | * | (1.06, 3.49) | 1.83 | * | (1.03, 3.23) |

| Bisexual non-white male | 1.24 | (0.62, 2.47) | 1.14 | (0.46, 2.81) | 1.00 | (0.43, 2.30) | 0.89 | (0.34, 2.38) | ||||

| Straight white female | 1.48 | *** | (1.39, 1.56) | 1.42 | *** | (1.33, 1.51) | 1.34 | *** | (1.27, 1.43) | 1.32 | *** | (1.24, 1.41) |

| Lesbian white female | 2.33 | *** | (1.70, 3.19) | 1.94 | *** | (1.41, 2.67) | 2.05 | *** | (1.46, 2.87) | 1.79 | *** | (1.28, 2.50) |

| Bisexual white female | 3.46 | *** | (2.16, 5.55) | 2.88 | *** | (1.78, 4.66) | 2.38 | *** | (1.41, 4.03) | 2.19 | ** | (1.31, 3.68) |

| Straight non-white female | 1.58 | *** | (1.44, 1.73) | 1.41 | *** | (1.27, 1.55) | 1.43 | *** | (1.30, 1.57) | 1.28 | *** | (1.16, 1.42) |

| Lesbian non-white female | 2.63 | *** | (1.60, 4.32) | 2.25 | ** | (1.34, 3.79) | 2.19 | ** | (1.29, 3.73) | 1.96 | * | (1.10, 3.48) |

| Bisexual non-white female | 3.11 | *** | (1.90, 5.11) | 2.55 | *** | (1.50, 4.33) | 2.65 | *** | (1.57, 4.47) | 2.24 | ** | (1.27, 3.92) |

| Age | 1.05 | *** | (1.05, 1.05) | 1.05 | *** | (1.05, 1.06) | 1.06 | *** | (1.05, 1.06) | 1.06 | *** | (1.05, 1.06) |

| Less than high school | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||

| High school diploma | 0.69 | *** | (0.63, 0.75) | 0.73 | *** | (0.66, 0.80) | 0.71 | *** | (0.65, 0.78) | 0.74 | *** | (0.67, 0.81) |

| Some college | 0.61 | *** | (0.56, 0.67) | 0.66 | *** | (0.60, 0.72) | 0.61 | *** | (0.55, 0.67) | 0.65 | *** | (0.59, 0.72) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.36 | *** | (0.33, 0.39) | 0.46 | *** | (0.42, 0.51) | 0.39 | *** | (0.36, 0.43) | 0.48 | *** | (0.44, 0.53) |

| Married | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||

| Never married | 1.15 | *** | (1.07, 1.24) | 1.23 | *** | (1.14, 1.33) | 1.19 | *** | (1.11, 1.29) | 1.26 | *** | (1.16, 1.37) |

| Separated/divorced | 1.40 | *** | (1.31, 1.49) | 1.27 | *** | (1.18, 1.36) | 1.22 | *** | (1.15, 1.31) | 1.16 | *** | (1.08, 1.24) |

| Widowed | 1.22 | *** | (1.11, 1.35) | 1.27 | *** | (1.15, 1.41) | 1.26 | *** | (1.15, 1.39) | 1.30 | *** | (1.18, 1.44) |

| Hispanic | 0.76 | *** | (0.69, 0.84) | 0.81 | *** | (0.73, 0.91) | 0.78 | *** | (0.70, 0.86) | 0.83 | *** | (0.75, 0.93) |

| Foreign born | 0.59 | *** | (0.53, 0.65) | 0.68 | *** | (0.62, 0.76) | 0.62 | *** | (0.56, 0.68) | 0.70 | *** | (0.63, 0.77) |

| Lifetime abstainer | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||||

| Former drinker | 1.34 | *** | (1.22, 1.46) | 1.25 | *** | (1.14, 1.37) | ||||||

| Light drinker | 0.94 | (0.86, 1.02) | 0.89 | ** | (0.82, 0.97) | |||||||

| Moderate/heavy drinker | 0.80 | *** | (0.72, 0.87) | 0.77 | *** | (0.71, 0.85) | ||||||

| Underweight | (ref) | (ref) | ||||||||||

| Normal weight | 0.58 | *** | (0.46, 0.72) | 0.60 | *** | (0.48, 0.75) | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.71 | ** | (0.56, 0.89) | 0.73 | ** | (0.59, 0.92) | ||||||

| Obese | 1.32 | * | (1.06, 1.65) | 1.33 | * | (1.07, 1.66) | ||||||

| Current smoker | 1.63 | *** | (1.52, 1.74) | 1.50 | *** | (1.40, 1.61) | ||||||

| Exercise 4+ times weekly | 0.67 | *** | (0.64, 0.72) | 0.68 | *** | (0.64, 0.72) | ||||||

| Trouble sleeping | 2.73 | *** | (2.60, 2.87) | 2.32 | *** | (2.20, 2.44) | ||||||

| No health insurance | 0.60 | *** | (0.54, 0.65) | 0.62 | *** | (0.56, 0.68) | ||||||

| Delayed medical care | 1.40 | *** | (1.26, 1.57) | 1.35 | *** | (1.20, 1.51) | ||||||

| Unmet medical care | 1.46 | *** | (1.29, 1.65) | 1.39 | *** | (1.22, 1.58) | ||||||

| Can’t afford health services | 2.27 | *** | (2.09, 2.47) | 1.94 | *** | (1.77, 2.13) | ||||||

| Save medication | 2.03 | *** | (1.90, 2.17) | 1.81 | *** | (1.68, 1.94) | ||||||

| N | 62,302 | 62,302 | 62,302 | 62,302 | ||||||||

Health behaviors and healthcare access explained only some of the gaps in functional limitation (Models 2–4 in Table 3). Although the functional health gaps by sexual identity between women were no longer present, the functional disadvantages for all women (compared with white or non-white straight men) remained significant.

Discussion

Population research on health disparities by sexual orientation has rarely examined how gender and race/ethnicity interact with sexual orientation to affect health experiences. Moreover, few studies have tested the relationship between health outcomes and health risk factors across sexual–gender–racial identity groups. The current study shows that sexual, gender, and racial identities interact with one another in a complex way to affect health. For both SRH and functional limitation, there is evidence supporting the non-additive perspective of intersectionality.20,21,23,26 Although sexual minority, female gender, and non-whiteness are generally associated with poorer health outcomes, the combinations of social identities (disadvantaged, privileged, or both) do not predict health in a linear or additive fashion. Groups with three disadvantaged identities do not necessarily fare worse than those with two disadvantaged identities, who in turn do not necessarily fare worse than groups with single disadvantaged identity. Nevertheless, conditional on sociodemographic factors, white straight men never exhibit worse health outcomes than any other group. The fact that non-white sexual minority women do not report worse health than white sexual minority women, white bisexual men, or non-white gay men corresponds to the resilience theory that the strengths/strategies developed to cope with sexism, racism, or heterosexism may buffer the deleterious health consequences of one another.16–18

Results also show that health disparities by sexual, gender, and racial identities vary according to the health outcome in question. In particular, the intersection effects of gender and sexuality on functional limitation are prominent, but race plays only a minor role. Rather, all sexual, gender, and racial identities interact with one another to affect SRH. Furthermore, although health behaviors and healthcare resources explain many of the SRH gaps by sexual–gender–racial identity, they only modestly explain the gaps in functional limitation. Specifically, the gender gap remains wide when behaviors and access to care are accounted for. Prior research suggests that functional limitations may take a longer time to develop and manifest.25,33 Therefore, proximal contributors to health, such as current health behaviors and access to health services, may not be expected to fully explain the gaps in functional limitation. Relatedly, interventions targeting behavioral change or enhancement of healthcare access may become less effective once physical functions are impaired. As the pattern of health disparity may differ from condition to condition, future research on intersectionality and health should explore a broader range of physical and mental health outcomes.

Limitations

A few limitations of the study should be noted. First, the data are cross-sectional, and the causal direction of the relationship between health risk factors and health outcomes cannot be determined. Although the relationship is most likely bidirectional, prior studies based on longitudinal data have validated the direction from exposure to risks to health. For example, sleep disturbance or deprivation may rouse inflammatory responses and increase the severity of physical disorders.34,35 Also, barriers to primary and preventive care predict declines in health and function and premature mortality.36 Second, the sample sizes for the bisexual groups (except white bisexual women) are relatively small, reducing the power of the statistical analysis for these groups. As such, the estimated ORs for these groups typically have wider CIs, and it is difficult to assess whether these groups are indeed more or less healthy than others. Moreover, owing to data limitation, only the sexual identity aspect of sexual orientation was considered here. As previous findings suggest that identity, behavior, and attraction intersect to affect health,37–39 findings from this study may not reflect the health experience of individuals who have same-sex behavior or attraction but do not identify as sexual minorities. In addition, though this study shows that behavioral risks and healthcare access contribute to health disparities, they are both proximal rather than fundamental determinants of health. Programs/policies that target these proximal health risks without addressing stigma and institutional discrimination against sexual/gender/racial minority groups may be ineffective in eliminating health disparities. Finally, the definition of gender is restricted and unable to reflect the plurality of gender identities. The study unfortunately cannot address the health concerns of transgender and other gender populations.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations, this study advances the understanding of the link between health behavior, healthcare access, and health outcomes among groups with different sexual, gender and racial identities. It suggests that research focusing on one-dimensional status (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, or sexual orientation) may miss the health risk or benefit related to a unique configuration of social identities. In particular, sexual minorities of different gender and race may be exposed to different types or unequal levels of health risk. Future research should continue the efforts to investigate the heterogeneity of health experiences by attending to multiply intersecting social statuses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research is partially supported by funding from NIH, including the National Institute on Aging (T32AG000243, P30AG012857). The funders played no role in the study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1953–1960. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamant AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, Gelberg L. Health behaviors, health status, and access to and use of health care: a population-based study of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1043. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archfami.9.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE. Disability Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults: Disparities in Prevalence and Risk. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):e16–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300379. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Cardiovascular Biomarkers Among Young Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(6):612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, Calzo JP, Everett B. Eating Disorder Symptoms and Obesity at the Intersections of Gender, Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation in US High School Students. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):e16–e22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehmer U, Miao X, Linkletter C, Clark MA. Adult health behaviors over the life course by sexual orientation. Am J Public Health. 2011;102(2):292–300. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS. Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):489–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponce NA, Cochran SD, Pizer JC, Mays VM. The effects of unequal access to health insurance for same-sex couples In California. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(8):1539–1548. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0583. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strutz KL, Herring AH, Halpern CT. Health Disparities Among Young Adult Sexual Minorities in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancey AK, Cochran SD, Corliss HL, Mays VM. Correlates of overweight and obesity among lesbian and bisexual women. Prev Med. 2003;36(6):676–683. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00020-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, Pizacani BA, Stark MJ. Demonstrating the Importance and Feasibility of Including Sexual Orientation in Public Health Surveys: Health Disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):460–467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130336. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis GB. Black-white differences in attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights. Public Opin Q. 2003;67(1):59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/346009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips L. Deconstructing “down low” discourse: The politics of sexuality, gender, race, AIDS, and anxiety. J Afr Am Stud. 2013;9(2):3–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12111-005-1018-4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moradi B, Wiseman MC, DeBlaere C, et al. LGB of Color and White Individuals’ Perceptions of Heterosexist Stigma, Internalized Homophobia, and Outness: Comparisons of Levels and Links. Couns Psychol. 2010;38(3):397–424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000009335263. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowleg L, Huang J, Brooks K, Black A, Burkholder G. Triple Jeopardy and Beyond: Multiple Minority Stress and Resilience Among Black Lesbians. J Lesbian Stud. 2003;7(4):87–108. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J155v07n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer IH. Identity, Stress, and Resilience in Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals of Color. Couns Psychol. 2010;38(3):442–454. doi: 10.1177/0011000009351601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000009351601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choo HY, Ferree MM. Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions, and Institutions in the Study of Inequalities*. Sociol Theory. 2010;28(2):129–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01370.x. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–1299. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1229039. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman BK, Denney JT, Dowdy H, Medeiros RA. A New Piece of the Puzzle: Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Physical Health Status. Demography. 2015;52(4):1357–1382. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0406-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grollman EA. Multiple disadvantaged statuses and health: The role of multiple forms of discrimination. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55(1):3–19. doi: 10.1177/0022146514521215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022146514521215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hankivsky O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(11):1712–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veenstra G. Race, gender, class, and sexual orientation: intersecting axes of inequality and self-rated health in Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics. A Brief Quality Assessment of the NHIS Sexual Orientation Data. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/qualityso2013508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li K-H, Meng X-L, Raghunathan TE, Rubin DB. Significance levels from repeated p-values with multiply-imputed data. Stat Sin. 1991;1(1):65–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchenko YV, Reiter JP. Improved degrees of freedom for multivariate significance tests obtained from multiply imputed, small-sample data. Stata J. 2009;9(3):388. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiter JP. Small-sample degrees of freedom for multi-component significance tests with multiple imputation for missing data. Biometrika. 2007;94(2):502–508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/asm028. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Vol. 81. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pavalko EK, Mossakowski KN, Hamilton VJ. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(1):18–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1519813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irwin MR, Wang M, Campomayor CO, Collado-Hidalgo A, Cole S. Sleep deprivation and activation of morning levels of cellular and genomic markers of inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(16):1756–1762. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1756. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.16.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffman C, Paradise J. Health insurance and access to health care in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136(1):149–160. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsieh N. Explaining the mental health disparity by sexual orientation: The importance of social resources. Soc Ment Health. 2014;4(2):129–146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2156869314524959. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight LFM, Hope DA. Correlates of same-sex attractions and behaviors among self-identified heterosexual university students. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(5):1199–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9927-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9927-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Downing MJ, Jr, Parsons JT. Disclosure and Concealment of Sexual Orientation and the Mental Health of Non-Gay-Identified, Behaviorally Bisexual Men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(1):141–153. doi: 10.1037/a0031272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.