Abstract

Introduction

To lower the barrier for initiating insulin treatment and obtain adequate glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), new basal insulin preparations with improved pharmacological properties and consequently a lower risk of hypoglycemia are needed. The objective of this trial was to confirm the efficacy and compare the safety of insulin degludec (IDeg) with insulin glargine (IGlar) in a multinational setting with two thirds of subjects enrolled in China.

Methods

This was a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, treat-to-target, non-inferiority trial in 833 subjects with T2DM (48 % were female, mean age 56 years, diabetes duration 8 years), inadequately controlled on oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs). Subjects were randomized 2:1 to once-daily IDeg (555 subjects) or IGlar (278 subjects), both with metformin. The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) after 26 weeks.

Results

The completion rate was high (IDeg 94.2 %; IGlar 91.4 %). Mean HbA1c decreased from 8.3 to 7.0 % in both groups. Estimated treatment difference (ETD) [95 % confidence interval (CI)] IDeg-IGlar in change from baseline was −0.05 % points [−0.18 to 0.08], confirming the non-inferiority of IDeg to IGlar. The proportion of subjects achieving HbA1c <7.0 % was 54.2 and 51.4 % with IDeg and IGlar, respectively (estimated odds ratio [95 % CI] IDeg/IGlar: 1.14 [0.84 to 1.54]). The mean decrease in fasting plasma glucose, self-measured plasma glucose profiles, and insulin dose were similar between groups. Numerically lower rates of overall (estimated rate ratio [95 % CI] IDeg/IGlar: 0.80 [0.59 to 1.10]) and nocturnal (0.77 [0.43 to 1.37]) confirmed hypoglycemia were observed with IDeg compared with IGlar. No treatment differences in other safety parameters were found. Subjects were more satisfied with the IDeg device compared with the IGlar device as reflected by the total Treatment Related Impact Measures-Diabetes Device score (ETD [95 % CI] IDeg-IGlar: 2.2 [0.2 to 4.3]).

Conclusion

IDeg provided adequate glycemic control non-inferior to IGlar and a tendency for a lower hypoglycemia rate. IDeg is considered suitable for initiating insulin therapy in T2DM patients on OADs requiring intensified treatment.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01849289.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40268-016-0134-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| New basal insulin preparations with improved pharmacological properties and consequently a lower risk of hypoglycemia are needed to lower the barrier for initiating insulin treatment and obtain adequate glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. The objective of this randomized, open-label, treat-to-target trial was to confirm the efficacy and compare the safety of insulin degludec (IDeg) with insulin glargine (IGlar) in a multinational setting with two thirds of subjects enrolled in China |

| The non-inferiority of IDeg to IGlar in glycemic control as measured by changes in glycosylated hemoglobin was confirmed, and the proportion of subjects reaching the glycemic targets of glycosylated hemoglobin <7.0 and ≤6.5 %, the decrease in fasting plasma glucose, self-measured plasma glucose profiles, and insulin doses at the end of treatment were similar between IDeg and IGlar. Furthermore, numerically lower rates of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemic episodes (by 20 and 23 %, respectively) were observed with IDeg compared with IGlar, although not statistically significantly different |

| Overall, once-daily IDeg provided adequate glycemic control non-inferior to IGlar and a tendency for a lower rate of hypoglycemia. IDeg is considered suitable for initiating insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes on oral antidiabetic drugs requiring intensified treatment |

Introduction

Globally, around 415 million people are living with diabetes mellitus, a number that is expected to rise with 227 million over the next 25 years. Approximately 90 % have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and the number of people with T2DM is currently increasing in every country [1]. Specifically, in China, the prevalence of diabetes has increased from less than 1 % in 1980 to 11.6 % in 2010, making China the country with the highest absolute disease burden of diabetes in the world [1, 2].

Accumulating evidence supports early initiation of insulin treatment in T2DM. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) demonstrated that intensive glycemic control in newly diagnosed patients with T2DM reduced long-term micro- and macrovascular complications [3]. Tight glycemic control early after diagnosis of T2DM may lead to slower progression of the disease and delay the need for intensified treatment [4]. Insulin is recommended as the most powerful option of second-line therapy in T2DM if individualized glycemic targets are not met within a reasonable time frame [5]. An important focus of insulin initiation in T2DM is that glycemic control should be achieved while still ensuring a low risk of hypoglycemia because the risk of hypoglycemia is a major reason for clinical inertia in initiating insulin treatment in T2DM [6]. Unfortunately, most current basal insulin analogs do not allow glycemic control over a full 24-h period, and are often limited by their day-to-day variability and thereby a potentially higher risk of hypoglycemia [7]. Therefore, basal insulin preparations with improved pharmacological properties and an even lower risk of hypoglycemia are needed.

Insulin degludec (IDeg) is an insulin analog with an ultra-long duration of action >42 h. Owing to a unique protraction mechanism with IDeg monomers being slowly and continuously released into the circulation, a stable glucose-lowering effect across 24 h and less day-to-day variability in the glucose-lowering effect has been observed with IDeg compared with insulin glargine (IGlar). With these pharmacological properties, IDeg allows for flexibility in dosing without compromising glycemic control or increasing the risk of hypoglycemia [7]. Clinical studies have confirmed that IDeg is non-inferior to IGlar in HbA1c reduction with once-daily dosing in insulin-naïve or insulin-treated patients with T2DM and causes a reduction in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) greater than or similar to that of IGlar [8–11]. Furthermore, meta-analyses have shown that in insulin-naïve patients with T2DM the total daily dose at end of trial was 10 % lower with IDeg than with IGlar [12], and that IDeg compared with IGlar reduced the rate of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemic episodes in patients with T2DM [13]. In addition, using the Treatment Related Impact Measures-Diabetes Device (TRIM-D Device) questionnaire [14], the IDeg delivery device has been rated significantly better for device function and with less device bother [15] compared with the IGlar delivery device.

The rationale for the current trial was to confirm the efficacy of IDeg and to compare the safety of IDeg with IGlar, both in combination with metformin in insulin-naïve patients with T2DM in a multinational trial, with two thirds of the patients enrolled in China to support IDeg registration in China.

Methods

Trial Design

This was a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, treat-to-target trial conducted at 68 centers in Brazil, Canada, China, South Africa, Ukraine, and United States between June 2013 and May 2014. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2000 and 2008 [16], and Good Clinical Practice [17]. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for being included in the trial. The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT01849289).

Subjects

The trial included insulin-naïve subjects with T2DM, who were inadequately controlled on oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) and qualified for intensified treatment. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were ≥18 years of age, had T2DM diagnosed clinically for ≥6 months, had HbA1c between 7.0 and 10.0 % (both inclusive), body mass index ≤40 kg/m2, were insulin naïve, and treated with stable doses of OADs (metformin monotherapy or in combination with an insulin secretagogue [sulfonylurea or glinide], dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor, or α-glucosidase-inhibitors [acarbose]) for ≥3 months prior to randomization. Exclusion criteria included treatment with thiazolidinedione or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists within the previous 3 months prior to screening, cardiovascular disease within 6 months prior to screening, uncontrolled severe hypertension, impaired hepatic or renal function, current or medical history of cancer, recurrent severe hypoglycemia, proliferative retinopathy or maculopathy, or use of non-herbal Chinese medicine with unknown content.

Randomization and Blinding

Eligible participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to insulin degludec (IDeg, 100 U/mL, 3 mL FlexTouch®; Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) or insulin glargine (IGlar, Lantus®, 100 U/mL, 3 mL SoloSTAR®; Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) once daily for 26 weeks. Randomization was performed using an interactive voice/web response system at each dispensing visit. Randomization was stratified according to region: China/non-China. The trial was open label, but treatment group assignment was blinded for internal titration surveillance committee members, internal safety committee members, external members of the cardiovascular event adjudication committee, and everyone involved in defining analysis sets and performing data review until the database was locked.

Procedures

At randomization, all subjects discontinued their OADs except for metformin, which was to be continued maintaining the pre-randomization dose level and dosing frequency throughout the trial. IDeg was administered once daily between the start of the main evening meal and bedtime, and IGlar was administered once daily according to local labeling. The starting dose of both insulin products was 10 U with dose titration each week. Mean value of pre-breakfast self-measured plasma glucose (SMPG) measured on 3 consecutive days before each scheduled visit or telephone contact was used for optimal titration according to a titration algorithm, with a target pre-breakfast SMPG of 4.0–4.9 mmol/L (Online Resource Table S1).

Blood samples for central laboratory-analyzed FPG and HbA1c, and measurements for nine-point SMPG profiles were collected before randomization and after 12, 16, and 26 weeks. Adverse events (AEs) and hypoglycemic episodes were collected throughout the trial. All other safety parameters were collected at the beginning and end of the trial, and for body weight and insulin antibodies also after 12 weeks. Patient-reported outcome questionnaires were completed at baseline and after 12 and 26 weeks. After 26 weeks, all subjects switched to Neutral Protamine Hagedorn insulin (NPH insulin, Insulatard®/Protaphane®/Novolin N™, 100 IU/mL, 3 mL FlexPen®) and continued using metformin for a 1-week follow-up period to allow for the measurement of insulin antibodies. A 1-week interval (corresponding to >5 × T½) was necessary to allow for washout of trial insulin. During this period, subjects were treated with NPH insulin, which owing to the much shorter half-life ensured lower insulin levels at the antibody sampling time point, consequently reducing the risk for interference with the antibody measurements.

Efficacy Assessments

The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in HbA1c (%) after 26 weeks of treatment. Secondary endpoints included responders in HbA1c (subjects achieving HbA1c <7 and ≤6.5 %), responders in HbA1c without confirmed hypoglycemic episodes during the last 12 weeks of treatment, change in central laboratory-measured FPG, nine-point SMPG profiles, within-subject variability (CV%) in pre-breakfast SMPG, and health-related quality of life (assessed by Short-Form 36 version 2.0 [SF-36] questionnaire [18]) and TRIM-D Device [14]. SMPG was measured using a blood glucose meter (Precision Xtra®/FreeStyle Optimum®; Abbott Diabetes Care Inc., Alameda, CA, USA) with test strips calibrated to plasma values.

Safety Assessments

Safety assessments included AEs, hypoglycemic episodes, injection-site reactions, insulin dose, body weight, and abnormal findings in physical examination, vital signs, fundoscopy, electrocardiogram, and laboratory assessments (hematology, biochemistry, lipids, urinalysis, and insulin antibodies). Laboratory analyses were performed by standard methods at Quintiles Central Laboratories (Beijing, China; West Lothian, UK; Marietta, GA; Centurion, South Africa), and Diagnósticos da América (São Paulo, Brazil). Insulin antibodies were measured using a subtraction radioimmunoassay method [19, 20] (Celerion, Fehraltorf, Switzerland). Confirmed hypoglycemic episodes were defined as either episodes with SMPG <3.1 mmol/L [21] (with or without symptoms) or severe episodes requiring assistance. Episodes occurring between 00:01 and 05:59 (both inclusive) were classified as nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes. Treatment-emergent AEs, including hypoglycemic episodes, were defined as those with onset date on or after the first day of exposure and until 7 days after the last day of treatment with IDeg or IGlar.

Statistical Analyses

The primary objective of the trial was to confirm the efficacy of IDeg plus metformin in controlling glycemia by comparing the difference in change from baseline in HbA1c (%) after 26 weeks between IDeg plus metformin and IGlar plus metformin to a non-inferiority limit of 0.4 %.

The sample size was based on having sufficient representation in China. The calculation of statistical power was performed for the primary objective with the assumption of a one-sided t test with a significance level of 2.5 %, a mean treatment difference of zero, and a standard deviation of 1.3 % for HbA1c. A total of 795 subjects had to be randomized to achieve a nominal power of 95 % in the evaluation of the per-protocol (PP) analysis under the assumption that 15 % of subjects would be excluded from the PP set.

All statistical analyses were performed on the full analysis set (comprising all randomized subjects) following the intention-to-treat principle. Efficacy and safety endpoints were summarized using the full analysis set and the safety analysis set (comprising all subjects exposed to treatment), respectively. For confirmatory endpoints, the overall type I error rate was controlled by means of a hierarchical testing procedure with a priori ordering of hypotheses [10]. Missing values were imputed using the last observation carried forward method [22].

The primary endpoint, treatment difference in change from baseline in HbA1c, was analyzed using an analysis of variance with treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex, and region (China/non-China) as fixed factors, and age and baseline HbA1c as covariates. Sensitivity analyses of the primary analysis were performed on the PP set, using the same model as above, on the full analysis set using a simple model including only treatment as a fixed factor and HbA1c baseline value as a covariate, and with a linear mixed model for repeated measures using an unstructured residual covariance matrix to evaluate the sensitivity of last observation carried forward for dealing with missing data.

Responders in HbA1c (for targets of <7 and ≤6.5 %), and responders achieving these targets without confirmed hypoglycemic episodes in the previous 12 weeks of treatment, were analyzed with a logistic regression model with logit link using treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex and region as fixed factors, and age and baseline HbA1c as covariates. The number of treatment-emergent hypoglycemic episodes was analyzed with a negative binomial regression model including treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex and region as fixed factors, age as a covariate, and log exposure as an offset.

Treatment differences in FPG, pre-breakfast SMPG, mean and fluctuation in 9-point SMPG, prandial plasma glucose (PG) increments, nocturnal PG differences, body weight, SF-36 and TRIM-D Device scores were analyzed similarly to the primary endpoint, using the relevant baseline value as covariate (if available). Within-subject variability (CV%) of pre-breakfast SMPG was estimated from a linear mixed model with treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex and region as fixed factors, age as a covariate, and subject as a random factor. All other endpoints were summarized descriptively. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Subject Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Of the 1168 subjects screened for eligibility, 335 subjects failed to meet the screening criteria and 833 subjects were randomized. In accordance with the 2:1 randomization ratio (IDeg:IGlar), 555 subjects were randomized to IDeg and 278 to IGlar. Two subjects in the IDeg group withdrew consent prior to receiving treatment. A total of 94.2 and 91.4 % of the randomized subjects completed the trial with IDeg and IGlar, respectively, the main reason for discontinuation being withdrawal of consent (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trial flow diagram. The full analysis set included all randomized subjects. The safety analysis set included all randomized subjects who received at least one dose of trial product. Most subjects withdrawn for “other” reasons were randomized in error (5 in the IDeg group, 3 in the IGlar group). % proportion of randomized subjects

The treatment groups were well matched at baseline with a duration of diabetes of approximately 8 years, and a mean HbA1c of 8.3 % (Table 1). The mean age was 56 years and women comprised approximately half of the subjects. Most subjects (67 %) were Asian non-Indian. Two thirds of subjects were from China (67 %), while the remaining subjects were evenly distributed between the other five countries (5–9 % of the subjects in each country). Subjects were insulin naïve at baseline, and approximately two thirds of subjects were treated with OAD combination therapy.

Table 1.

Demography and baseline characteristics (full analysis set)

| IDeg OD (n = 555) | IGlar OD (n = 278) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 256 (46.1) | 146 (52.5) |

| Race | ||

| White | 133 (24.0) | 70 (25.2) |

| Black or African American | 12 (2.2) | 9 (3.2) |

| Asian Indian | 8 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Asian non-Indian | 375 (67.6) | 187 (67.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 26 (4.7) | 11 (4.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 47 (8.5) | 23 (8.3) |

| Age, years | 55.9 (9.7) | 56.6 (9.2) |

| Body weight, kg | 75.5 (15.6) | 73.8 (16.1) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (4.7) | 27.0 (4.6) |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus, years | 7.55 (5.28) | 8.26 (5.45) |

| HbA1c, % | 8.3 (0.9) | 8.3 (0.8) |

| FPG, mmol/L | 9.4 (2.4) | 9.4 (2.5) |

| Antidiabetic regimen at screening, n (%) | ||

| Metformin monotherapy | 189 (34.1) | 87 (31.3) |

| Metformin + 1 OAD | 314 (56.6) | 159 (57.2) |

| Metformin + >1 OAD | 52 (9.4) | 31 (11.2) |

| Metformin + 1 OAD + insulin therapy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| OADs at screening, n (%) | ||

| Metformin | 555 (100.0) | 278 (100.0) |

| Sulfonylurea | 290 (52.3) | 159 (57.2) |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitor | 66 (11.9) | 38 (13.7) |

| Glinide | 34 (6.1) | 15 (5.4) |

| DPP-IV inhibitor | 29 (5.2) | 10 (3.6) |

| Complications at screening, n (%) | ||

| Diabetic complicationsa | 133 (24.0) | 67 (24.1) |

| Vascular disorders | 314 (56.6) | 147 (52.9) |

Data are mean (standard deviation) based on the full analysis set unless otherwise stated

IDeg insulin degludec, IGlar insulin glargine, OD once daily, % proportion of subjects, BMI body mass index, HbA 1c glycosylated hemoglobin, FPG fasting plasma glucose, OAD oral antidiabetic therapy, DPP-IV dipeptidyl peptidase IV

aDiabetic complications included: diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy hemorrhage, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic nephropathy, microalbuminuria, diabetic vascular disorder, diabetic microangiopathy, diabetic macroangiopathy, diabetic ketoacidosis

Glycemic Control

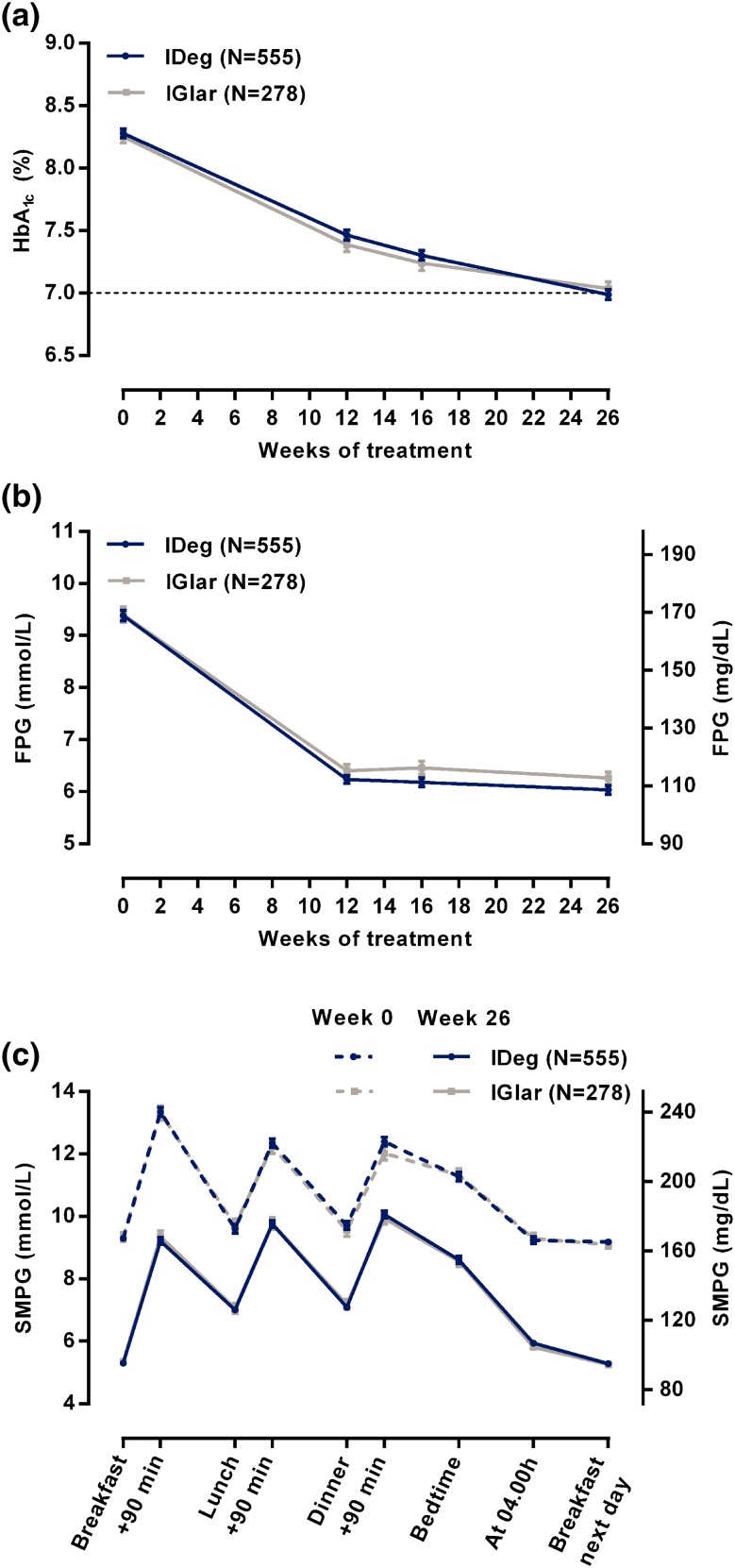

Mean HbA1c over time was similar between the treatment groups (Fig. 2a). During the 26-week treatment period, mean (standard deviation [SD]) HbA1c decreased from 8.3 (0.8) % to 7.0 (0.9) % in both treatment groups, consistent with the treat-to-target design. The groups showed similar mean (SD) changes from baseline in HbA1c; −1.3 (1.1) % points for IDeg and −1.2 (1.0) % points for IGlar. The estimated treatment difference (ETD) IDeg-IGlar [95 % CI] was −0.05 % points [−0.18 to 0.08] confirming the non-inferiority of IDeg to IGlar in HbA1c reduction. The result of the primary analysis was supported by similar results in the PP analysis and additional sensitivity analyses (Online Resource Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Glycemic control (full analysis set). a Mean HbA1c across the 26-week treatment period, b mean FPG across the 26-week treatment period, c 9-point SMPG profiles at baseline (week 0) and end of treatment (week 26). Glucose measurements for 9-point profiles were performed just before a meal and 90 minutes after start of the meal. Data are mean ± SEM. Missing data after baseline are imputed with the last observation carried forward method. IDeg insulin degludec, IGlar insulin glargine, HbA 1c glycosylated hemoglobin, FPG fasting plasma glucose, SMPG self-measured plasma glucose, +90 min 90 min after start of the preceding meal, SEM standard error of the mean

The proportion of subjects who achieved the HbA1c target of <7.0 % at the end of the trial was comparable; 54.2 % with IDeg and 51.4 % with IGlar (estimated odds ratio, EOR [95 % CI] IDeg/IGlar: 1.14 [0.84 to 1.54]). Similarly, the proportion of subjects who achieved the more strict target of ≤6.5 was 35.7 and 31.3 % with IDeg and IGlar, respectively (EOR [95 % CI]: 1.23 [0.89 to 1.70]). The proportion of subjects achieving HbA1c <7.0 % without confirmed hypoglycemia in the previous 12 weeks of treatment was 46.8 % with IDeg and 42.4 % with IGlar. The odds of achieving this target was numerically higher in the IDeg group with EOR [95 % CI] of 1.24 [0.91 to 1.69], although not statistically significant. Similarly, the proportion of subjects achieving the target of ≤6.5 % in HbA1c without confirmed hypoglycemia was 31.8 and 26.4 % in the IDeg and IGlar groups, respectively (EOR [95 % CI]: 1.33 [0.94 to 1.87]).

The decrease in FPG over time was similar between treatments with the most pronounced decrease during the first 12 weeks and almost unchanged in the remaining part of the treatment period (Fig. 2b). The mean (SD) FPG at baseline was 9.4 (2.4) mmol/L in the IDeg group and 9.4 (2.5) mmol/L in the IGlar group. After 26 weeks of treatment, FPG had decreased by 3.35 (2.91) mmol/L with IDeg and 3.14 (2.71) mmol/L with IGlar to mean (SD) levels of 6.0 (2.0) mmol/L and 6.3 (1.9) mmol/L, respectively. The ETD [95 % CI] for IDeg-IGlar in change from baseline in FPG was −0.26 mmol/L [−0.53 to 0.02] and did not reach statistical significance.

The nine-point SMPG profiles appeared similar between the two treatment groups at baseline and at the end of trial and similar reductions in PG levels were observed for both treatment groups (Fig. 2c). The within-subject variability in pre-breakfast SMPG as measured by CV% was 14.2 % with IDeg and 12.9 % with IGlar (estimated treatment ratio [95 % CI] IDeg/IGlar of 1.10 [1.02 to 1.18]).

Insulin Doses

In both treatment groups, the mean daily basal insulin dose was 10 U (0.14 U/kg) at baseline, corresponding to the pre-defined starting dose, and increased throughout the trial, most rapidly during the initial weeks (Online Resource Fig. S1). At the end of trial, mean daily basal insulin doses were similar in the treatment groups; 0.49 U/kg (40 U) for IDeg and 0.50 U/kg (39 U) for IGlar.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measurements

The total score (device bother and device function) for TRIM-D Device at the end of treatment was 74.3 in the IDeg group and 71.6 in the IGlar group, with a statistically significant difference between treatments in favor of IDeg (ETD [95 % CI] IDeg-IGlar: 2.2 [0.2 to 4.3]).

The physical and mental scores of the SF-36 questionnaire improved marginally in both groups during the trial. No statistically significant differences were shown between IDeg and IGlar in any of the SF-36 domains.

Hypoglycemic Episodes

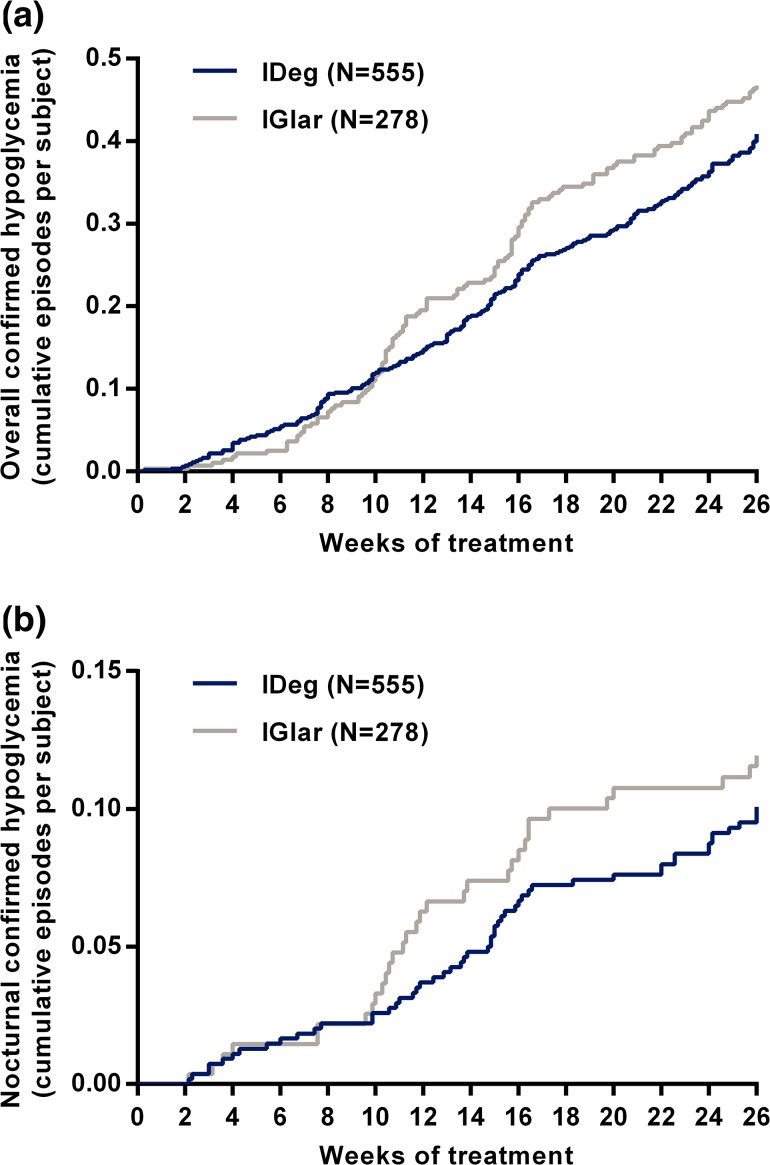

The rate of confirmed hypoglycemia was 85 and 97 episodes per 100 patient-years of exposure with IDeg and IGlar, respectively. IDeg was associated with a 20 % lower rate of confirmed hypoglycemia, although not statistically significant (estimated rate ratio, [95 % CI] IDeg/IGlar: 0.80 [0.59 to 1.10]) (Table 2). The rate of nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemia was 22 and 24 episodes per 100 patient-years of exposure in the IDeg and IGlar groups, respectively, with an estimated rate ratio [95 % CI] for IDeg/IGlar of 0.77 [0.43 to 1.37] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency and analysis of hypoglycemic episodes (safety and full analysis sets)

| IDeg OD (n = 553) | IGlar OD (n = 278) | Estimated rate ratio IDeg/IGlar [95 % CI] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects n (%) | Episodes | Ratea | Subjects n (%) | Episodes | Ratea | ||

| Overall severeb | 2 (0.4) | 2 | 1 | 2 (0.7) | 2 | 1 | ND |

| Overall confirmedc | 128 (23.1) | 228 | 85 | 79 (28.4) | 130 | 97 | 0.80 [0.59 to 1.10] |

| Nocturnal confirmedc,d | 40 (7.2) | 58 | 22 | 25 (9.0) | 32 | 24 | 0.77 [0.43 to 1.37] |

Summary statistics for the safety analysis set and statistical analysis on the full analysis set

The estimated rate ratio was analyzed in a negative binomial regression model including treatment, antidiabetic therapy at screening, sex and region as fixed factors, age as covariate, and log exposure as offset. Statistical analysis of severe hypoglycemic episodes was not performed because of too few episodes

IDeg insulin degludec, IGlar insulin glargine, OD once daily, CI confidence interval, ND not done

aNumber of hypoglycemic episodes per 100 patient-years of exposure

bRequiring assistance of another person to actively administer carbohydrate, glucagons, or other resuscitative actions

cIncludes episodes of severe hypoglycemia as well as hypoglycemic episodes with confirmed plasma glucose <3.1 mmol/L

dTime of onset between 00:01 and 05:59 (both inclusive)

Across the entire 26-week trial period, IDeg had a constant rate of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemic episodes, while IGlar had a low rate in the initial part of the trial and an increasing rate as the trial progressed (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative number of confirmed hypoglycemic episodes across the 26-week treatment period (safety analysis set). a Overall confirmed hypoglycemic episodes. b Nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemic episodes. Confirmed hypoglycemic episodes included episodes of severe hypoglycemia as well as hypoglycemic episodes with confirmed plasma glucose <3.1 mmol/L. Nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes were defined as episodes with time of onset between 00:01 and 05:59 (both inclusive). IDeg insulin degludec, IGlar insulin glargine

Two severe hypoglycemic episodes were reported by two subjects in each group (0.4 and 0.7 % of subjects for IDeg and IGlar, respectively) (Table 2). Owing to the low number of severe episodes no statistical analysis was performed.

Adverse Events

In total, 53 % of subjects treated with IDeg and 58 % of subjects treated with IGlar reported at least one treatment-emergent AE during the trial (Online Resource Table S3). Most of the events (97 %) were of mild or moderate severity. A total of 11.9 % of subjects treated with IDeg and 10.8 % of subjects treated with IGlar reported AEs assessed as probably or possibly related to trial product. The most frequently reported AEs in each treatment group were upper respiratory tract infection and nasopharyngitis, both of which were reported in ≥5 % of subjects. The proportion of subjects with injection-site reactions was low and similar between treatment groups (1.6 % in the IDeg group and 0.7 % in the IGlar group). In total, six subjects withdrew because of AEs, three (0.5 %) in the IDeg group and three (1.1 %) in the IGlar group, and no specific pattern of AEs leading to withdrawal was noted.

Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported by 2.9 % of subjects (16/553) in the IDeg group and 3.6 % of subjects (10/278) in the IGlar group. No SAEs were reported with a frequency ≥1 % in either treatment group. Of the SAEs, 4 of 18 events were considered possibly or probably related to IDeg and 3 of 12 events were considered possibly or probably related to IGlar. The SAEs considered related to IDeg were hypoglycemia, cerebral infarction, cerebrovascular accident, and hypoglycemic unconsciousness (one episode each), and SAEs considered related to IGlar were two episodes of hypoglycemia and one episode of palpitations.

Three serious and one non-serious malignant neoplasms were reported during the trial. In the IDeg group, non-small-cell metastatic lung cancer and basal cell carcinoma (non-serious) were reported, and in the IGlar group, rectal cancer and gastric cancer were reported. All malignant neoplasms were considered unrelated to the trial product.

One death occurred during the trial in the IGlar group. The cause of death was reported as cardiac failure, peritonitis, and gastric cancer with perforation, and was considered unrelated to treatment.

A total of six major adverse cardiovascular events were reported, distributed similarly between groups; four strokes in the IDeg group (0.7 % of subjects) and two strokes in the IGlar group (0.7 % of subjects).

Other Safety Results

Body weight increased similarly throughout the trial in both treatment groups with mean (SD) weight gain in the IDeg and IGlar groups of 2.2 (3.1) and 1.8 (3.1) kg, respectively (ETD [95 % CI] IDeg-IGlar: 0.34 kg [−0.09 to 0.78]). There were no clinically relevant differences between treatments in laboratory analyses (hematology, biochemistry, lipids, and urinalysis), physical examination findings, electrocardiogram, vital signs, or fundoscopy/fundus photography during the trial. The mean level of insulin antibodies specific for IDeg and IGlar was zero at baseline and did not change during the trial. Only single cases of IDeg/IGlar-specific antibodies were detected during the treatment period. Mean values (SD) of insulin antibodies cross-reacting between IDeg/IGlar and human insulin increased from 2.0 (8.7) % bound/total with IDeg and 1.6 (7.5) % bound/total with IGlar at baseline to 3.2 (11.1) % bound/total for IDeg and 4.9 (12.5) % bound/total for IGlar at the end of the wash-out. Only a minor fraction of subjects in the IDeg and IGlar treatment groups developed cross-reacting antibodies. No correlation between cross-reacting or insulin-specific antibodies and HbA1c or insulin dose was observed.

Discussion

In this trial, treatment with IDeg in a T2DM population with 67 % Chinese subjects, initiating insulin treatment confirmed its efficacy and safety when compared with IGlar. In accordance with previous trials in the large clinical development program for IDeg, non-inferiority vs. IGlar in terms of glycemic control was met [8–10]. Despite the large sub-population of Chinese subjects with an assumed high carbohydrate intake [23], basal-only treatment ensured adequate glycemic control in a large proportion of subjects (HbA1c <7.0 %; 54 % with IDeg and 51 % with IGlar) without requiring additional bolus insulin.

As shown by the total TRIM-D Device score, subjects were more satisfied with the IDeg device compared with the IGlar device. The result in this trial is consistent with a previous crossover trial where subjects were randomized to receive either IDeg or IGlar for 16 weeks, and were crossed over to the alternative basal insulin for the remaining 16 weeks [15]. In that trial, an even larger treatment difference in TRIM-D Device score in favor of IDeg was seen. Importantly, subjects in that trial were using insulin vials and syringes prior to the trial; thus, the results were not affected by recent insulin pen experience, similarly to the trial reported here where the subjects were insulin naïve.

The treat-to-target design allows for direct comparison of safety measurements such as hypoglycemia without confounding differences in HbA1c. In this trial, 20 and 23 % lower rates of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemia, respectively, were found with IDeg compared to IGlar, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). This was accompanied by the odds of achieving the glycemic targets of HbA1c <7 and ≤6.5 % without confirmed hypoglycemia being 24 and 33 % higher with IDeg than with IGlar, although not statistically significantly different. Similar results have been seen in other IDeg trials of 26 weeks duration [8, 9], and a statistically significant difference in nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemia rates was shown in a 52-week trial (36 % lower rate for IDeg compared with IGlar) [10]. A pre-specified meta-analysis has been conducted to confirm superiority of IDeg over IGlar for hypoglycemic episodes using pooled individual subject-level data from seven previous IDeg trials. For basal-only insulin treatment in insulin-naïve subjects with T2DM, the meta-analysis showed rates of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemic episodes that were statistically significantly lower by 17 and 36 %, respectively, for IDeg compared with IGlar [13]. Recently, a meta-analysis performed on the same data, using three alternative definitions of nocturnal hypoglycemia, supported statistically significantly lower rates of nocturnal hypoglycemia in the range of 27–44 % with IDeg vs. IGlar in insulin-naïve subjects with T2DM [24]. Thus, the numerical differences in hypoglycemia rate between IDeg and IGlar observed in the present trial are in accordance with comprehensive pooled analyses of previous trials in insulin-naïve subjects with T2DM on basal-only therapy.

In this trial, the within-subject day-to-day variation in pre-breakfast SMPG, assessed by CV% was 12.9 % with IGlar and 14.2 % with IDeg, with the difference between treatments being statistically significant. In other trials testing IDeg vs. IGlar in T2DM with basal-only insulin treatment, generally higher levels of within-subject variability in pre-breakfast SMPG were seen (CV% of 16–18 %) with statistically significantly lower CV% in favor of IDeg [9], or no difference between treatments [8, 10]. Thus, the observed difference in the present trial is not believed to be of any clinical relevance.

The trial had several strengths. Including an insulin-naïve population ensured that expectation bias was reduced. Furthermore, the treat-to-target design used to achieve improved and similar glycemic control in the two treatment groups ensured that comparisons among groups in frequency and severity of hypoglycemia were interpretable in ultimate risk-benefit assessments [22]. The trial was limited by the open-label design, but because appropriate placebo injection devices were not available, it was not possible to employ a fully blinded double-dummy design. Still, because accurate quantification of hypoglycemic episodes was important, we tried to limit reporting bias by using an objective definition of hypoglycemia, i.e., either PG <3.1 mmol/L [21] (where the majority of subjects will have symptoms) or severe hypoglycemia requiring assistance. As in any open-label trial, there was a risk of greater caution when titrating the dose of the new drug (IDeg); however, when comparing IDeg with IGlar this was not reflected in the change in HbA1c and FPG over time, or in the proportion of subjects reaching HbA1c targets at the end of the trial. Because the dosing time of IGlar was not captured in this trial, it was not possible to explore the impact of dosing time on glycemic control. Finally, as in any other clinical trial, the population was selected based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, implying that the clinical applicability of this trial is limited to patients who fit those criteria.

Conclusion

This trial confirmed the non-inferiority of IDeg vs. IGlar in HbA1c reduction when initiating once-daily basal insulin in patients with T2DM. IDeg provided adequate glycemic control with a low rate of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemia, and no safety issues were detected. Overall, the findings from this trial, with two thirds of subjects enrolled in China, demonstrate that IDeg provides a new and safe option for initiating insulin therapy in insulin-naïve patients with T2DM who are inadequately controlled on OADs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This trial was conducted and sponsored and the article processing charges funded by Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark). The authors thank the investigators, trial staff, and patients for their participation, and Mads Jeppe Tarp-Johansen (Novo Nordisk) for researching data and contributing to the manuscript. Writing and submission assistance was provided by Lillian Jespersen and Carsten Roepstorff, Larix A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark) supported by Novo Nordisk. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Jorge L. Gross received consulting honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, MannKind Corporation, and Novo Nordisk. Robert Wagner received consulting honoraria and research support from Novo Nordisk. Changyu Pan and Wenying Yang have attended the advisory board of Novo Nordisk and been speakers for Novo Nordisk. Charlotte Thim Hansen is employed by and owns stock in Novo Nordisk. Hongfei Xu is employed by Novo Nordisk. Xiaofeng Lv and Li Sun declare no conflicts of interest.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for being included in the trial.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Foundation. Diabetes atlas. 7th edition 2015. Available from http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. Accessed 18 Feb 2016.

- 2.Xu Y, Wang L, He J, et al. 2010 China Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance Group. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA. 2013;310:948–959. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.168118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanefeld M. Use of insulin in type 2 diabetes: what we learned from recent clinical trials on the benefits of early insulin initiation. Diabetes Metab. 2014;40:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58:429–442. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahrén B. Avoiding hypoglycemia: a key to success for glucose-lowering therapy in type 2 diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:155–163. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S33934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haahr H, Heise T. A review of the pharmacological properties of insulin degludec and their clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:787–800. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0165-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gough SC, Bhargava A, Jain R, Mersebach H, Rasmussen S, Bergenstal RM. Low-volume insulin degludec 200 units/ml once daily improves glycemic control similarly to insulin glargine with a low risk of hypoglycemia in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 26-week, randomized, controlled, multinational, treat-to-target trial: the BEGIN LOW VOLUME trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2536–2542. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onishi Y, Iwamoto Y, Yoo SJ, Clauson P, Tamer SC, Park S. Insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine in insulin-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes: a 26-week, randomized, controlled, Pan-Asian, treat-to-target trial. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:605–612. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinman B, Philis-Tsimikas A, Cariou B, et al. NN1250-3579 (BEGIN Once Long) Trial Investigators. Insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 1-year, randomized, treat-to-target trial (BEGIN Once Long) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2464–2471. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garber AJ, King AB, Del Prato S, et al. NN1250-3582 (BEGIN BB T2D) Trial Investigators. Insulin degludec, an ultra-longacting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal-bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes (BEGIN Basal-Bolus Type 2): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, treat-to-target non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1498–1507. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vora J, Christensen T, Rana A, Bain SC. Insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of endpoints in phase 3a trials. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(2):435–446. doi: 10.1007/s13300-014-0076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratner RE, Gough SC, Mathieu C, et al. Hypoglycaemia risk with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine in type 2 and type 1 diabetes: a pre-planned meta-analysis of phase 3 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:175–184. doi: 10.1111/dom.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brod M, Hammer M, Christensen T, Lessard S, Bushnell DM. Understanding and assessing the impact of treatment in diabetes: the Treatment-Related Impact Measures for Diabetes and Devices (TRIM-Diabetes and TRIM-Diabetes Device) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:83. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren M, Chaykin LB, Jabbour SA, et al. Efficacy, patient-reported outcomes (PRO) and safety of insulin degludec U200 vs. insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) requiring high-dose insulin (Poster 1040-P). Presented at the American Diabetes Association, 75th Annual Scientific Sessions; 2015 June 5–9; Boston, MA, USA. Available from: https://ada.scientificposters.com/epsSearchADA.cfm. Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

- 16.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Seoul: 59th WMA General Assembly; 2008.

- 17.International Conference on Harmonisation. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6 (R1), Step 4; 1996.

- 18.Turner-Bowker DM, Bartley PJ, Ware JE. SF-36® Health survey and “SF” bibliography. Third Edition (1988–2000). Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002.

- 19.Lindholm A, Jensen LB, Home PD, Raskin P, Boehm BO, Råstam J. Immune responses to insulin aspart and biphasic insulin aspart in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:876–882. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mire-Sluis AR, Barrett YC, Devanarayan V, et al. Recommendations for the design and optimization of immunoassays used in the detection of host antibodies against biotechnology products. J Immunol Methods. 2004;289:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muchmore DB, Heinemann L, Tamborlane W, Wu XW, Fleming A. Assessing rates of hypoglycemia as an end point in clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e160–e161. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.FDA, USDHHS, and CDER. Guidance for industry: diabetes mellitus: developing drugs and therapeutic biologics for treatment and prevention, 2008. Available from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm071624.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

- 23.Hu EA, Pan A, Malik V, Sun Q. White rice consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis and systematic review. BMJ. 2012;344:e1454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heller S, Mathieu C, Kapur R, Wolden ML, Zinman B. A meta-analysis of rate ratios for nocturnal confirmed hypoglycaemia with insulin degludec vs. insulin glargine using different definitions for hypoglycaemia. Diabet Med. 2016;33:478–487. doi: 10.1111/dme.13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.