Abstract

The selectivity filter of K+ channels contains four ion binding sites (S1–S4) and serves dual functions of discriminating K+ from Na+ and of acting as a gate during C-type inactivation. C-type inactivation is modulated by ion binding to the selectivity filter sites but the underlying mechanism is not known. Here we evaluate how the ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the KcsA channel participate in C-type inactivation and in recovery from inactivation. We use unnatural amide-to-ester substitutions in the protein backbone to manipulate the S1–S3 sites and a side chain substitution to perturb the S4 site. We develop an improved semisynthetic approach for generating these amide-to-ester substitutions in the selectivity filter. Our combined electrophysiological and X-ray crystallographic analysis of the selectivity filter mutants show that the ion binding sites play specific roles during inactivation and provide insights into the structural changes at the selectivity filter during C-type inactivation.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

K+ channels play important roles in essential cellular processes such as the maintenance of the resting membrane potential, the excitation of nerve and muscle cells, the secretion of hormones, and sensory transduction.(Hille, 2001) Important for the physiological function of K+ channels is their ability to selectively conduct K+.(Hille, 2001) The ion conduction pathway in a K+ channel is contained within the pore domain whose topology is conserved in the K+ channel family (Fig. 1a).(MacKinnon et al., 1998) Selection for K+ takes place in the narrow region of the ion pathway referred to as the selectivity filter.(MacKinnon, 2004) The selectivity filter consists of a row of four K+ binding sites that are built using the main chain carbonyl oxygen atoms and the threonine side chain from the protein sequence T-V-G-Y-G (Fig. 1b).(Doyle et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2001) This sequence is highly conserved in K+ channels and known structures of K+ channels show a similar structure for the selectivity filter. (Jiang et al., 2003; Long et al., 2007; Tao et al., 2009)

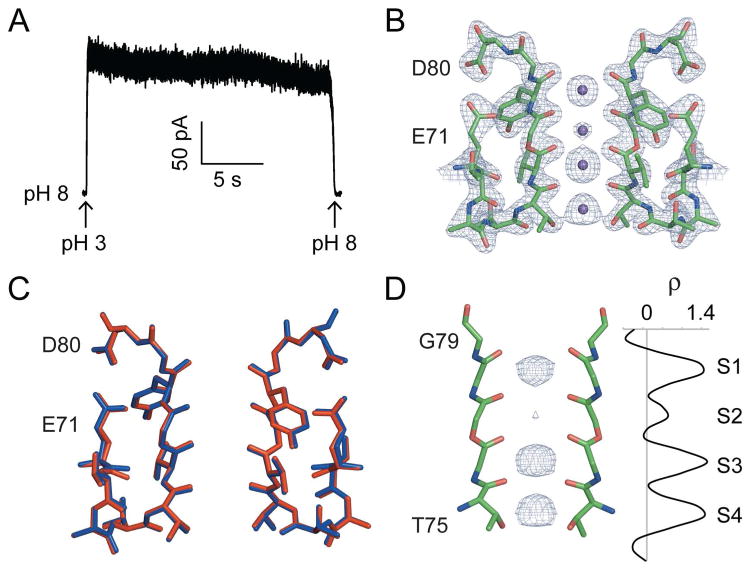

Figure 1. The selectivity filter and inactivation in the KcsA channel.

a) Structure of the wild type KcsA channel (PDB: 1K4C). Two opposite subunits of the tetramer are shown with the selectivity filter (residues T75-G79) depicted as sticks and K+ ions bound to the selectivity filter shown as spheres. b) Close-up of the selectivity filter of the KcsA channel. The amide bonds (1′-4′) and the ion binding sites (S1–S4) are labeled. The Fo-Fc electron density (residues 75–79, ions and lipid omitted) present at the ion binding sites is shown, contoured at 3.0 σ. A one-dimensional plot (1-D) of the electron density sampled along the central axis of the selectivity filter is shown (right). c) The gating cycle of the KcsA channel. Four states are depicted with the selectivity filter in either the conductive or the inactivated state and the bundle crossing in either the closed or the open state. The changes at the bundle crossing and the selectivity filter are coupled. Opening of the bundle crossing favors the inactivated state of the selectivity filter while closure of the bundle crossing favors the conductive state. d) Macroscopic currents for the KcsA channel were elicited at +80 mV by two pulses to pH 3.0 with a variable time interval (recovery time) at pH 8.0 between pulses. The fraction recovery was measured as the ratio of the peak current in the second pulse to the peak current in the first pulse. Inset: The fraction recovery plotted as a function of the recovery time at pH 8.0. Points represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from 3–4 patches and the solid line is a fit to a single exponential function. e) Amide-to-ester mutagenesis.

In addition to determining K+ selectivity, the selectivity filter acts as a gate to regulate the flow of ions.(Hoshi and Armstrong, 2013; Kurata and Fedida, 2006; McCoy and Nimigean, 2012) This process of gating at the selectivity filter has been extensively investigated in voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels and is referred to as C-type (or slow) inactivation.(Hoshi et al., 1991) During C-type inactivation, conformational changes at the selectivity filter convert it from a conductive to a non-conductive state. While there is a large body of experimental work implicating the selectivity filter in C-type inactivation, the molecular details of the conformational changes that take place at the selectivity filter to restrict the movement of ions are not known.(Hoshi and Armstrong, 2013; Kurata and Fedida, 2006) The movement of ions through the pore domain is additionally controlled by the activation gate, which is formed by the bundle crossing of the transmembrane helices at the cytoplasmic side of the pore (Fig. 1a).(Jiang et al., 2002; Liu et al., 1997; Perozo et al., 1999) In the closed state, the bundle crossing obstructs the movement of K+ through the pore (Fig. 1c). Channel activation causes a widening of the helix bundle to permit the flow of K+ through the pore. The process of activation and C-type inactivation are coupled.(Cuello et al., 2010a; Panyi and Deutsch, 2006) The opening of the activation gate triggers C-type inactivation at the selectivity filter while the closure of the activation gate is required for the selectivity filter to recover from the inactivated state to the conductive state. This balance of the rates of inactivation and recovery determines the number of K+ channels available for subsequent activation and therefore determines the excitability of the cell.(Hoshi and Armstrong, 2013)

Gating of ion conduction at the selectivity filter is also observed in channels that do not belong to the Kv family such as the bacterial K+ channel, KcsA. KcsA is a pH-gated channel that is activated by a decrease in intracellular pH that opens the gate at the bundle crossing.(Cuello et al., 1998) Activation of the KcsA channel results in a rapid increase in current and is followed by inactivation, during which the current spontaneously decays to a low steady value (Fig. 1d).(Chakrapani et al., 2007; Cordero-Morales et al., 2006a; Gao et al., 2005) Recovery of the channel from inactivation requires closure of the activation gate, which takes place for the KcsA channel with a change in the intracellular pH from acidic to neutral values (Fig. 1d).(Chakrapani et al., 2007) This process of inactivation in the KcsA channel is functionally similar to C-type inactivation in Kv channels.(Cordero-Morales et al., 2006b; Cordero-Morales et al., 2011; Cordero-Morales et al., 2007; Cuello et al., 2010b) This similarity, combined with the easy amenability of KcsA to structural and spectroscopic studies, has made it an important experimental system to investigate the process of C-type inactivation.(Ader et al., 2009; Bhate and McDermott, 2012; Cuello et al., 2010b; Imai et al., 2010)

It has been established that ion binding to the selectivity filter modulates C-type inactivation but the underlying mechanism is not known.(Kurata and Fedida, 2006) In this work, we address how the ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the KcsA channel participate in inactivation and recovery from inactivation. Our approach is to perturb ion binding at specific sites in the filter and determine the role of each site in inactivation and recovery. The S1–S3 sites (see Fig. 1b for nomenclature) in the selectivity filter are made up entirely by the carbonyl oxygens of the protein backbone and to manipulate these sites, we use amide-to-ester substitutions in the protein backbone (Fig. 1e). An ester bond is isosteric to an amide bond but shows lower electronegativity at the carbonyl oxygen, by roughly one half.(Powers et al., 2005) The lower electronegativity at the liganding oxygens leads to lower ion binding at the site. As the protein backbone is not accessible to traditional site directed mutagenesis, we use protein semisynthesis to introduce the ester substitutions into the selectivity filter. Semisynthesis is a very powerful approach for protein engineering as it allows protein modification using chemical synthesis.(Muir, 2003) Semisynthesis consists of assembly of the polypeptide from recombinant and synthetic fragments using native chemical ligation (NCL), followed by in vitro folding to the native state. NCL is a coupling reaction between a C-terminal thioester peptide and an N-terminal Cys peptide that results in linking the peptides with a native peptide bond.(Dawson et al., 1994) Recently, we applied this backbone mutagenesis approach to alter ion occupancy at the S1 and S2 sites to investigate their roles in inactivation.(Matulef et al., 2013) We found that decreasing ion occupancy at the S1 site with the G79ester substitution did not affect the rate of inactivation, while decreasing occupancy at the S2 site with the Y78ester substitution nearly eliminated inactivation. We also found that the G77ester mutation nearly eliminated inactivation. At that time, technical limitations of the semisynthetic approach prevented us from generating sufficient yields of the G77ester channel for structural studies or from generating sufficient yields of the V76ester for functional or structural studies.

Here we develop an improved semisynthetic approach for generating amide-to-ester substitutions in the selectivity filter. We use this modified semisynthetic approach along with traditional mutagenesis to alter ion occupancy at all the ion binding sites in the selectivity filter. By using a combination of structural and functional approaches, we determine the roles of the selectivity filter sites in inactivation and in recovery from inactivation. The distinct roles of the ion binding sites provide insights into the structural changes at the selectivity filter that underlie C-type inactivation.

Results

An optimized semisynthetic approach for introducing ester substitutions in the selectivity filter

To alter ion occupancy at the S3 site, we sought to generate the KcsA V76ester channel in which the 4′ amide bond in the selectivity filter is replaced with an ester linkage. This was a synthetically challenging endeavor as the 4′ amide bond links two β-branched amino acids, Thr75 and Val76 (Fig. 1b). Forming an ester linkage between residues with a β-branched side chain is difficult due to steric hindrance.(Kent, 1988) We initially attempted semisynthesis of the V76ester channel using the previously reported two-part approach.(Matulef et al., 2013; Valiyaveetil et al., 2004) For introducing the ester substitution using semisynthesis, the ester linkage is initially incorporated into a synthetic peptide, which is then used for the assembly of the KcsA channel. The two part semisynthesis calls for the incorporation of the V76ester linkage into a 55 amino acid long peptide. This approach was not successful as were not able to synthesize the V76ester peptide required in sufficient yields. Next, we explored using the three part “modular” semisynthesis.(Komarov et al., 2009) In the modular approach, the KcsA channel is assembled from three peptides-a synthetic peptide thioester (pore peptide) which encompasses the selectivity filter and two recombinant peptides corresponding to the rest of the channel (Fig. 2a). The peptides are coupled together by two sequential NCL reactions followed by in vitro folding to the native state. The key advantage of the modular approach is that the peptide into which the ester linkage has to be incorporated is relatively short-12 amino acids compared to 55 amino acids for the two-part approach. The shorter length is advantageous in both the synthesis and purification of the ester containing peptide.

Figure 2. Modular semisynthesis of the KcsA V76ester channel.

a) Strategy for the semisynthesis of the KcsA V76ester channel. The KcsA polypeptide is synthesized from two recombinant peptides (gray, N-peptide thioester: residues 1–69 and C-peptide: 82–160) and a synthetic pore peptide thioester (red, residues 70–81) by two sequential native chemical ligation reactions. The V76ester linkage in the pore peptide is indicated by an asterisk. The first ligation reaction between the C-peptide and the pore peptide thioester yields an intermediate peptide. The Thz protecting group (green sphere) on the N-terminal cysteine of the intermediate peptide is removed, and the intermediate peptide is then ligated to the N-peptide thioester to yield the KcsA polypeptide. The KcsA polypeptide is folded in vitro to the native state. The ligation sites, residues 70 and 82, are represented by yellow boxes or spheres. b) SDS-PAGE gel (15%) of the first ligation reaction between the C-peptide (C) and the V76ester pore peptide (residues 70–81, with the peptide bond between residues 75 and 76 replaced with an ester linkage) to form the intermediate peptide (I) at 0 min (lane 1) and 2 h (lane 2). c) SDS-PAGE gel (15%) of the second ligation reaction between the N-peptide thioester (N) and the intermediate peptide to form the KcsA polypeptide (F) at 0 min (lane 1) and 24 h (lane 2). d) SDS-PAGE gel (12%) showing the folding of semisynthetic KcsA by lipids. The unfolded monomeric (M, which corresponds to the KcsA polypeptide) and the folded tetrameric KcsA (T) are indicated. e) Size exclusion chromatography of the purified V76ester KcsA channel. Inset: SDS-PAGE gel (12%) showing molecular weight markers (lane 1) and the purified V76ester channel (lane 2).

For the synthesis of the V76ester pore peptide, we initially attempted to generate the ester linkage between Thr75 and Val76 using the previously published conditions, but obtained poor yields.(Matulef et al., 2013; Valiyaveetil et al., 2006b) To improve the yields, we tested alternate coupling reagents and identified COMU (1-[(1-(cyano-2-ethoxy-2-oxoethylideneaminooxy)-dimethylaminomorpholinomethylene)]-methanaminium-hexafluorophosphate) as the optimal coupling reagent for introducing the ester linkage.(Twibanire and Grindley, 2011) This modification enabled synthesis of the V76ester pore peptide in good yields. We used the V76ester pore peptide to assemble the KcsA polypeptide by NCL reactions and folded it to the native tetrameric state using the lipid-based in vitro folding procedure to obtain the KcsA V76ester channels (Fig. 2b, c, d). The KcsA V76ester mutant channels were purified from the lipid vesicles for functional and structural studies (Fig. 2e). Using our optimized modular approach, we were able to routinely generate ~0.5 mg of the purified KcsA V76ester channel. In addition to the V76ester mutant, we used this modular approach for the assembly of the G79ester and the G77ester channels in good yields.

Functional and structural effects of the V76ester substitution in the selectivity filter

We incorporated the purified KcsA V76ester channels into lipid vesicles and used liposome patch clamping for measuring channel activity. Macroscopic currents for the V76ester channel were elicited by a pH jump from 8.0 to 3.0 on the cytoplasmic side and showed rapid activation followed by inactivation (Fig. 3a). The rate of inactivation of the V76ester mutant was slightly slower (~ 2 fold) compared to the control channel (Table 1). We used a paired pH pulse protocol to measure the recovery from inactivation and observed that recovery from inactivation was dramatically slower (~30 fold) in the V76ester mutant compared to the control (Fig. 3b, Table 1).

Figure 3. Functional and structural effects of the V76ester substitution.

a) Macroscopic currents for the KcsA V76ester channel were elicited at +80 mV by a rapid change in pH. b) Recovery from inactivation in the V76ester (red triangles) and the control channel (black circles). The control channel contains the amino acid substitutions (S69A, V70C, and Y82C) that are present in the semisynthetic channels. Data points represent the mean ± SD from 3–10 patches. The solid lines are single exponential fits. c) Structure of the selectivity filter of the V76ester channel. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 2.8 σ for diagonally opposite subunits is shown with residues 71–80 represented as sticks and the K+ ions in the filter represented as spheres. d) Superposition of selectivity filter of wild type (blue) and the V76ester channel (red).

Table 1.

Inactivation parameters

| Effect on Ion Occupancy | τinactivation (ms) | If/Io | τrecovery (s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Recombinant | 1820 ± 641 (16) | 0.06 ± 0.04 (16) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | |

| Control* | Recombinant | 2803 ± 729 (9) | 0.17 ± 0.10 (9) | 2.5 ± 0.4 | |

| G79ester | Semisynthetic | S1 ↓ | 3636 ± 1786 (9) | 0.19 ± 0.07 (9) | 3.0 ± 0.8 |

| Y78ester** | Recombinant | S2 ↓ | NA | 0.64 ± 0.09 (4) | NA |

| G77ester | Semisynthetic | S2 ↓ | NA | 0.80 ± 0.15 (6) | NA |

| V76ester | Semisynthetic | S3 ↓ | 5821 ± 1971 (12) | 0.26 ±0.12 (12) | 81.3 ± 14.8 |

| T75G | Recombinant | S4 ↓ | 6512 ± 2663 (11) | 0.29 ±0.14 (11) | 30.3 ± 4.0 |

| G77dA | Semisynthetic | --- | 2850 ± 1760 (6) | 0.23 ± 0.10 (6) | 3.2 ± 0.7 |

| V76ester+G77dA | Semisynthetic | S3 ↓ | 2414 ± 526 (12) | 0.19 ± 0.05 (12) | 36.7 ± 1.9 |

Numbers represent mean ± standard deviation. If/Io is fraction of the current remaining at the end of the inactivation pulse divided by the peak current. The number of experiments are shown in parentheses. Standard deviations reported for τrecovery were determined from the fits as described in the methods.

Control KcsA channel contains the S69A, V70C, Y82C substitutions that were required for semisynthesis and are present in the semisynthetic channels.

Recombinantly expressed using the nonsense suppression method (Matulef et al., 2013)

To investigate the effect of the V76ester substitution on the structure and ion occupancy in the selectivity filter, we determined the crystal structure of the V76ester channel. For structure determination, the V76ester channel was crystallized as a complex with Fab.(Zhou et al., 2001) These attempts yielded crystals that diffracted to 2.9 Å resolution. The structure was determined by molecular replacement and the electron density map corresponding to the selectivity filter of the V76ester mutant is shown (Fig. 3c, Table 2). Superposition of the selectivity filters of the V76ester and the wild type KcsA channel reveals no appreciable differences in the protein structures (Fig. 3d). Unlike the wild type KcsA channel, which shows roughly equal ion occupancy at the four ion binding site (Fig. 1b, (Zhou and MacKinnon, 2003)), the V76ester shows no detectable electron density at the S3 site (Fig. 3C) indicating that the V76ester substitution specifically decreases ion binding to the S3 site.

Table 2.

Crystallographic data collection and model refinement statistics

| V76ester | V76ester+G77dA | G77ester | T75G conductive | T75G constricted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB id | 5EC1 | 5EC2 | 5EBW | 5EBL | 5EBM |

| Space Group | I4 | I4 | I4 | I4 | I4 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a,b,c (Å) | 155.6,155.6, 75.64 | 154.8, 154.87, 75.703 | 156.91, 156.91, 75.837 | 155.41, 155.41, 76.27 | 155.72,155.72, 75.556 |

| α,β, γ(°) | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 |

| Detector | ALS RDI_8M CMOS | ALS RDI_8M CMOS | ALS RDI_8M CMOS | ALS RDI_8M CMOS | ALS RDI_8M CMOS |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| CC1/2 | 0.998 (0.746) | 0.999 (0.841) | 0.998 (0.785) | 0.998 (0.708) | 0.999 (0.781) |

| I/σI | 15.5 (2.0) | 15.6 (2.4) | 13.1 (2.2) | 14.6 (2.0) | 17.4 (2.1) |

| Completeness | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.0) | 100 (100) | 100.0 (100.0) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 14.7 (13.9) | 7.4 (7.4) | 7.5 (7.4) | 7.2 (7.1) | 7.1 (7.2) |

| No. total reflections | 293,467 | 231,082 | 306,427 | 256,726 | 199,097 |

| No. unique reflections | 20,012 | 31,160 | 41,049 | 35,730 | 27,981 |

| Rwork/Rfreea | 24.4/26.8 | 23.0/25.9 | 22.2/24.9 | 20.5/24.2 | 21.6/25.1 |

| rmsd of bond lengths, Å | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| rmsd of bond angles, ° | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| Ramachandran plot b | |||||

| Favored, % | 96 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| Allowed, % | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Outlier, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Numbers in parentheses are statistics for the last resolution shell.

R = Σ|Fo - Fc|/ΣFo. 10% of the reflections that were excluded from the refinement were used in the Rfree calculation.

Performed in MolProbity

Ion occupancy at the S3 site is required for recovery from inactivation

To verify that our conclusions on the effect of the V76ester substitution on the structure and ion occupancy were not skewed by the moderate resolution of the data, we pursued crystals that diffracted to a higher resolution. To this end, we introduced an additional G77→D-Alanine (dA) substitution as the KcsA-G77dA channel readily crystallizes and affords crystals that diffract to a higher resolution.(Valiyaveetil et al., 2006a) Further, the G77dA substitution does not alter the structure or ion occupancy of the selectivity filter and importantly, does not alter that rate of C-type inactivation or recovery from inactivation (Fig. 4a, b, d, Table 1).(Devaraneni et al., 2013; Valiyaveetil et al., 2006a)

Figure 4. Incorporating the G77dA substitution into the KcsA V76ester channel.

a) Macroscopic currents for the KcsA G77dA channel elicited at +80 mV by a rapid change in pH. b) The ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the KcsA G77dA channel (PDB: 2IH3). Two opposite subunits are shown as sticks. Side chains of V76 and Y78 are omitted for clarity. The Fo-Fc electron density (KcsA residues 75–79, K+ ions, and lipid omitted) along the central axis of the selectivity filter contoured at 3.0 σ is shown. The one-dimensional plot of the electron density is shown on the right. c) Macroscopic currents for the KcsA V76ester+ G77dA channel elicited at +80 mV by a rapid change in pH. d) Recovery from inactivation in the G77dA (black triangles) and the V76ester+G77dA channels (red squares). Data points represent the mean ± SD from 3–6 patches. The solid lines are single exponential fits. e) Structure of the selectivity filter of the V76ester+G77dA channel. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 2.8 σ is shown with residues 71–80 of the channel represented as sticks and K+ ions in the filter represented as spheres. f) Superposition of residues 71–80 of the V76ester+G77dA channel (red) with the G77dA (blue, PDB: 2IH3) and the wild type channels (grey, PDB: 1K4C). g) The ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the V76ester+G77dA KcsA channel. The Fo-Fc electron density (KcsA residues 75–79, K+ ions, and lipid omitted) contoured at 3.0 σ is shown along the central axis of the selectivity filter. The one-dimensional plot of the electron density is shown on the right.

We synthesized a pore peptide with the V76ester+G77dA substitutions and used the modular approach for assembly of the KcsA V76ester+G77dA channel. Functional measurements on the KcsA V76ester+G77dA channels showed a rate of inactivation that was similar to the wild type control (or the G77dA channel) while the recovery from inactivation was ~15 fold slower than the control (Fig. 4c, d, Table 1). The inactivation properties of the KcsA V76ester+G77dA channel are therefore qualitatively similar to the V76ester channel.

As anticipated, we were able to obtain structural data to a higher resolution (2.5 Å) with the V76ester+G77dA channel (Table 2). The electron density of the selectivity filter region is shown in Fig. 4e. A superposition of the selectivity filter of the V76ester+G77dA channel with the G77dA and the wild type KcsA channels is shown in Fig. 4f. The structure of the V76ester+G77dA mutant channel is basically identical to the G77dA channel. Comparison to the wild type channel structure shows a slight rotation of the Y78 side chain, which is also observed in the G77dA structure. The electron density corresponding to K+ ions in the selectivity filter shows a decrease in the electron density at the S3 site, indicating substantially reduced ion binding specifically at the S3 site in the mutant channel (Fig. 4g). We observe a very slight shift (~0.1 Å) of the S2 and S4 ions towards the S3 site.

The major effect of the V76ester substitution is to reduce ion occupancy at the S3 site and the functional effect is to impair recovery from inactivation. Our results therefore suggest that recovery from inactivation requires ion occupancy at the S3 site. Further, we observe a similar effect on inactivation due to the V76ester substitution in the wild type or the G77dA background. The G77dA substitution blocks the selectivity filter from attaining the constricted or the collapsed state that is observed for the KcsA channel at low K+ concentrations or with the activation gate in the open state.(Cuello et al., 2010b; Devaraneni et al., 2013; Valiyaveetil et al., 2006a; Zhou et al., 2001) These measurements therefore also indicate that the impaired recovery observed with the V76ester substitution does not arise due to the filter transitioning to the constricted state.

Ion occupancy at the S2 site is required for inactivation

The S3 binding site is formed by the carbonyl oxygens of the 3′ and the 4′ amide bond (Fig. 1b). We have previously demonstrated that the 3′ amide-to-ester substitution (G77ester) impairs the ability of the channel to undergo C-type inactivation.(Matulef et al., 2013) The 3′ carbonyl oxygen contributes to both the S2 and S3 sites. To determine the effect of the 3′ ester substitution on the ion occupancies at these sites, we solved the structure of the KcsA G77ester channel. We were able to assemble the KcsA G77ester channel using either the modular approach or the two part semisynthesis. Functional measurements on the KcsA G77ester channel showed a lack of inactivation, as previously reported (Fig. 5a).(Matulef et al., 2013) We determined the crystal structure of the KcsA G77ester and refined it to 2.3 Å resolution. The electron density corresponding to the selectivity filter is shown in Fig. 5b. A superposition of the G77ester and the wild type channel (Fig. 5c) shows that the ester substitution is well tolerated with no noticeable structural changes in the ion binding sites or in the amino acid side chains surrounding the selectivity filter. The G77ester mutant shows altered ion occupancy in the selectivity filter with the ester substitution nearly eliminating all ion occupancy at the S2 site while having no effect on the ion occupancies at the other sites (Fig. 5d). We observe a slight shift in the positions of the S1 and S3 ions (~0.3 Å) towards the S2 site. The Y78ester substitution that has a similar phenotype of reduced C-type inactivation also shows reduced ion occupancy at the S2 site (Supp. Fig. 1).(Matulef et al., 2013) The results observed with the Y78ester and the G77ester channels therefore indicate that lower ion occupancy at the S2 site impairs inactivation.

Figure 5. Effects of the G77ester substitution on inactivation and ion distribution in the selectivity filter.

a) Macroscopic currents elicited at +80 mV for the KcsA G77ester channels by a rapid change in pH. b) Structure of the selectivity filter of the KcsA G77ester channel. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 2.8 σ is shown with residues 71–80 of the channel represented as sticks and K+ ions in the filter represented as spheres. c) Superposition of residues 71–80 of the KcsA G77ester (red) and the wild type channel (blue). d) The ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the G77ester channel. The Fo-Fc electron density (KcsA residues 75–79, K+ ions, and lipid omitted) along the central axis of the selectivity filter contoured at 2.5σ is shown. The one-dimensional plot of the electron density is shown on the right.

Ion occupancy at the S1 site is not important for inactivation or recovery

Next, we investigated the role of ion binding at the S1 site in C-type inactivation. The S1 site has been proposed as the locus for the conformational changes that result in C-type inactivation.(Armstrong and Hoshi, 2014; Hoshi and Armstrong, 2013) The G79ester substitution in the selectivity filter reduces ion occupancy at the S1 site and therefore we used the KcsA G79ester channel to evaluate the role of the S1 site (Fig. 6a).(Valiyaveetil et al., 2006b) We assembled the full length G79ester channel using the modular approach. We observed that the rate of inactivation in the KcsA G79ester channel was very similar to the wild type channel, as previously reported (Fig. 6a, Table 1).(Matulef et al., 2013) Measurements of recovery from inactivation indicated that the recovery also took place with a time course that was very similar to the wild type control (Fig. 6c, Table 1). These results show that the ion occupancy at the S1 site in the selectivity filter does not play a critical role in inactivation or in recovery in KcsA.

Figure 6. Inactivation and recovery in the KcsA G79ester channel.

a) The ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the KcsA G79ester channel. Two opposite subunits are shown in stick representation (PDB: 2H8P). Fo-Fc electron density (KcsA residues 75–79, K+ ions, and lipid omitted) along the central axis of the selectivity filter contoured at 3.0 σ is shown. b) Macroscopic currents for the KcsA G79ester channel elicited at +80 mV by a rapid change in pH. c) Recovery from inactivation of G79ester (red squares) and control channels (black circles). Data points represent the mean ± SD from 3–5 patches and the solid line represents an exponential fit to the data for the G79ester channel.

Ion occupancy at the S4 site enhances recovery from inactivation

The hydroxyl group of Thr75 contributes to the S4 site (Fig. 1b). To elucidate the role of this site, we used side chain substitutions that remove the hydroxyl group. We initially tested the T75C substitution as loss of ion binding at the S4 site in this mutant has been crystallographically demonstrated.(Zhou and MacKinnon, 2004) We were unable to detect macroscopic currents for the T75C mutant and therefore, we investigated other amino acid substitutions that also remove the hydroxyl group. Of the substitutions tested, we were able to measure robust macroscopic currents for the T75G mutant. We found that the T75G KcsA channel inactivates with a rate that was slightly (~2 fold) slower than the wild type channel, while recovery was significantly impaired (~10 fold slower than the wild type, Fig. 7a, b, Table 1). We determined the structure of the T75G mutant to confirm that the Gly substitution does indeed affect the S4 site (Table 2). The electron density corresponding to the selectivity filter is shown in Fig. 7c and shows the loss of the S4 site. A superposition of the selectivity filter of the T75G and the wild type channel indicates that there are no structural changes in the selectivity filter other than the missing S4 site (Fig. 7d). We observe some electron density at a lower site that we refer to as the S4′ site and the 1D plot also shows a slight reduction in the ion occupancy at the S2 site, similar to the KcsA T75C mutant (Fig. 7e).(Zhou and MacKinnon, 2004) The major effects of the T75G substitution-loss of the S4 site and the reduction in the rate of recovery from inactivation, indicate that ion occupancy at the S4 site is important for recovery from inactivation.

Figure 7. Effects of the T75G substitution on inactivation and ion distribution in the selectivity filter.

a) Macroscopic currents for the KcsA T75G channels elicited at +80 mV by a rapid change in pH. b) Recovery from inactivation in the KcsA T75G (blue open circles), V76 ester (red triangles), and wild type channels (black closed circles). Data points represent the mean ± SD from 3–7 patches and the solid lines are single exponential fits. Data for the V76ester and the wild type channel are from figures 3b and 1d respectively. c) Structure of the selectivity filter of the KcsA T75G channel. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 2.5 σ is shown with residues 71–80 of the channel represented as sticks and K+ ions in the filter represented as spheres. d) Superposition of residues 71–80 of the KcsA T75G (red) and the wild type channel (blue). e) The ion binding sites in the selectivity filter of the T75G channel. The Fo-Fc electron density (KcsA residues 75–79, K+ ions, and lipid omitted) along the central axis of the selectivity filter contoured at 3.0 σ is shown. The one-dimensional plot of the electron density for the T75G (red) and the wild type (black) channel is shown on the right.

Surprisingly, some crystals of the T75G mutant were found to have the selectivity filter in a non-conductive conformation that was similar to the constricted state (Supp. Fig. 2). Our results with the G77dA substitution clearly demonstrate that the constricted state does not correspond to the C-type inactivated state ((Devaraneni et al., 2013), Fig. 4C and 4D) and therefore the physiological significance of this non-conductive conformation of the T75G mutant is presently not obvious.

Discussion

Here we evaluate how the ion binding sites in the K+ selectivity filter participate in C-type inactivation and in recovery from inactivation. We use amide-to-ester substitutions in the protein backbone of the selectivity filter to alter ion occupancy at the S1–S3 sites and use a T75G substitution to alter ion occupancy at the S4 site. We find that ion occupancy at the lower sites, S3 and S4, is required for recovery from inactivation, while ion occupancy at the S2 site is required for entry into the inactivated state (Fig. 8a). Additionally, we find that ion occupancy at the S1 site does not influence either inactivation or recovery. Our studies therefore reveal surprisingly distinct roles for the ion binding sites in the inactivation process.

Figure 8. A working model for C-type inactivation.

a) Summary of the effects of ion occupancy at the selectivity filter sites on inactivation and recovery. b) Schematic diagram of the selectivity filter in the conductive and the inactivated states. The conformational change at the selectivity filter leading to C-type inactivation is proposed to be a rotation of the 4′ carbonyl oxygen that results in a disruption of the S3 and S4 sites. The inactivated state contains an ion bound at the S2 site. Recovery from inactivation involves a rotation of the 4′ carbonyl oxygen back into the conduction pathway to regenerate the S3 and the S4 sites. K+ ions are represented as purple spheres. The 4′ carbonyl oxygen is indicated by an asterisk and the direction of movement is indicated by blue arrows.

The amide bonds in the selectivity filter form H-bonds with the surrounding residues and the amide-to-ester substitution results in the deletion of this H-bond.(Zhou et al., 2001) The functional effects of the ester substitutions on inactivation could potentially also arise due to the disruption of the H-bond. However, the crystal structures for the 1′, 3′, and 4′ester substitutions, which effect ion occupancies at the S1, S2, and S3 sites respectively, show that these ester substitutions do not cause any appreciable changes in the structure of the selectivity filter or the surrounding residues. Further, the 2′ and 3′ ester substitutions have similar effects on ion occupancy and inactivation, even though they disrupt different H-bonds (Supp. Fig. 1). Based on these observations, we can rule out disruption of the H-bond as the major cause for the functional effects of the ester substitutions on the inactivation process. The ester bond also shows a lower rotational barrier compared to an amide bond. However, the ester linkage has a strong preference for the trans conformation and the energy barrier for rotation of the ester bond is 10–15 kcal/mol (compared to 18–21 kcal/mol for an amide bond).(Choudhary and Raines, 2011) The barrier for rotation is sufficiently high that the ester substitution is not expected to cause an increase in dynamics of the peptide backbone. In support, we observe in the crystal structures that the ester linkages are ordered similarly to the neighboring amide bonds. We can therefore conclude that the functional effects of the ester substitutions on inactivation are predominantly due to the changes in ion occupancy at the selectivity filter sites.

The 2′, 3′ and 4′ carbonyl oxygens, which are affected by the Y78ester, G77ester, and V76ester substitutions respectively, are involved in coordinating ions at two sites (Fig. 1b). Yet, our structural studies show that these ester substitutions specifically decrease ion occupancy at only one site. The Y78ester and G77ester decrease ion occupancy at the S2 site, whereas the V76ester decreases ion occupancy specifically at the S3 site. We do not know the chemical reason for this specificity of the ester substitutions, but this fortuitous effect allowed us to investigate the role of the individual ion binding sites.

Our findings that ion occupancy at the S3 and the S4 sites is important for recovery from inactivation are consistent with the studies on the Shaker K+ channel reported by Deutsch et. al., which concluded that recovery from inactivation is dependent on ion binding to a selectivity filter site that is towards the intracellular side.(Ray and Deutsch, 2006) Our findings are not in accord with the constricted or the dilated state models that have been put forth to describe the C-type inactivated state. The constricted model for the inactivated state was based on crystal structures of the KcsA channel trapped with the cytoplasmic gate open or in the presence of low concentrations of K+.(Berneche and Roux, 2005; Cuello et al., 2010b; Yellen, 2001; Zhou et al., 2001) We confirmed our previous findings that the G77dA substitution, which blocks the constricted state, does not alter the rate and extent of inactivation or the rate of recovery.(Devaraneni et al., 2013) This result demonstrates that the constricted state of the selectivity filter does not correspond to the physiologically relevant inactivated state. Further, the constricted state model predicts that inactivation proceeds through the loss of ion occupancy at the S2 site while we observe that loss of ion occupancy at the S2 site (which we find with either the 2′ or the 3′ ester substitutions) actually impairs inactivation.(Berneche and Roux, 2005; Cuello et al., 2010b) The dilation model, which is based on studies of eukaryotic Kv channels, proposes that C-type inactivation involves a widening of the S1 site, thereby rendering the channel non-conductive.(Hoshi and Armstrong, 2013) We observe that a reduction in ion occupancy at the S1 site does not influence either inactivation or recovery from the inactivated state. Therefore, our results also do not support the dilated model for the C-type inactivated state. Our conclusions are based on studies of the KcsA channel, and it is possible that differences exist in mechanism of inactivation in KcsA and other K+ channels.

Our results provide clues on the ion binding sites that are distorted on inactivation and suggest a working model for the structural changes that take place during inactivation (Fig. 8b). For the S1 site, the lack of an effect on inactivation from a decrease in ion occupancy suggests that inactivation does not involve any changes at this site. The requirement of ion occupancy at the S2 site for channels to inactivate suggests that the inactivated state must contain an intact S2 site. For the S3 and S4 sites, we observe that ion occupancy is required for recovery from inactivation, which suggests that the inactivated state involves a distortion of S3 and S4 sites. This distortion could be a simple structural change such as a rotation of the 4′amide bond that moves the carbonyl oxygen away from the ion conduction pathway. Such a rotation of the 4′ carbonyl oxygen will render the S3 and S4 sites unable to coordinate a K+ ion and will create a barrier to the movement of ions through the filter. Recovery from inactivation would then involve the rotation of the 4′ carbonyl oxygen back into the ion conduction pathway to reform the S3 and S4 sites, a process that is stabilized by ion binding to these sites.

Our model is based on the changes to the inactivation process that are caused by altering the ion occupancy in the conductive state of the selectivity filter. In our crystal structures, the cytoplasmic activation gate is closed while inactivation requires an open activation gate. This difference in the state of the activation gate does not affect our conclusions as the ion occupancy of the selectivity filter (in the conductive state) is not expected to change on opening of the activation gate. This expectation is based on structural studies of the KvAP and the Kv1.2 channels(Jiang et al., 2003; Long et al., 2007), which were crystallized in the open-conductive state and show ion occupancies in the selectivity filter that are similar to the KcsA channel in the closed-conductive state.

C-type inactivation is a complex process that involves structural changes beyond the ion binding sites. There is a large body of evidence indicating that the structural changes on C-type inactivation involves amino acid side chains surrounding the selectivity filter and the extracellular vestibule.(Cordero-Morales et al., 2006b; Cordero-Morales et al., 2011; Cordero-Morales et al., 2007; Larsson and Elinder, 2000; Liu et al., 1996; Loots and Isacoff, 1998; Pless et al., 2013; Raghuraman et al., 2014) Our results shed light on the role of selectivity filter sites during the inactivation process. Further studies will be necessary to determine how the changes in the selectivity filter sites during inactivation are propagated through the amino acid side chains surrounding the selectivity filter to the extracellular vestibule. Also presently unknown is the mechanism by which C-type inactivation is triggered by the opening of the activation gate.

This study highlights the utility of unnatural mutagenesis approaches for probing ion channel mechanisms. Conformational changes at the ion binding sites in the selectivity filter have been proposed to be important in the function of the BK channel, 2-pore K+ channels and also for channels outside the K+ channel family such as TRP and CNG channels.(Contreras et al., 2008; Flynn and Zagotta, 2001; Piechotta et al., 2011; Piskorowski and Aldrich, 2006; Thompson and Begenisich, 2012; Toth and Csanady, 2012) We anticipate that the amide-to-ester backbone mutagenesis strategy used in this study will be useful to elucidate the functional roles of the ion binding sites in these channels.

Methods Summary

The G79ester, G77ester, V76ester and the V76ester +G77dA ester mutants of the KcsA channel were generated using the modular semisynthetic approach.(Komarov et al., 2009) In the modular approach, the KcsA polypeptide is assembled from the three component peptides, a synthetic pore peptide corresponding to the selectivity filter and two recombinant fragments corresponding to the rest of the KcsA channel subunit. The peptides were linked together by two sequential native chemical ligation reactions followed by in vitro folding to the native state. To generate the ester mutants of the KcsA channel, the desired ester linkage was introduced during the synthesis of the pore peptide. The modular semisynthetic approach yields the full length protein. Various steps of the modular semisynthesis were optimized as described in the supplementary materials to improve the yields of the ester mutants. The KcsA G77ester channel used for structure determination was assembled using the two part semisynthesis as previously described.(Matulef et al., 2013) The wild type and the T75G KcsA channels were expressed as previously described.(Doyle et al., 1998) The semisynthetic and the recombinant KcsA channels were purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography.

For functional studies, the purified KcsA channel mutants were reconstituted into lipid vesicles and channel activity was assayed by liposome patch clamping. Macroscopic currents for inactivation measurements were elicited by a pH jump from 8.0 to 3.0 on the cytoplasmic side. The time constants for inactivation were determined by single exponential fits. Recovery from inactivation was determined using a two pulse protocol, with two activating steps to pH 3.0 separated by a variable recovery time at pH 8.0. The fractional recovery was determined by the ratio of the peak current in the second pulse to the first pulse. The recovery time constant (τrecovery) was determined by a fit to the equation where F is the fractional recovery and t is the time interval at pH 8.0.

For crystallization of the KcsA channel mutants, the purification tags present and the C-terminal 35 amino acids (if present) were removed by proteolysis. The truncated KcsA channels were crystallized as a complex with an antibody Fab fragment from KcsA-IgG.(Zhou et al., 2001) Structures were solved by molecular replacement using the wild type KcsA channel structure (pdb: 1k4c) with the selectivity filter residues 75–79 omitted as the search model. The structures were modelled in COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and refined using Phenix.(Adams et al., 2010) Model geometry was assessed using MolProbity.(Chen et al., 2010) Fo-Fc maps shown were calculated with KcsA residues 75–79, K+ ions and lipid omitted and are depicted along the central axis of the selectivity filter. One dimensional plots of electron density were calculated as previously described.(Morais-Cabral et al., 2001; Zhou and MacKinnon, 2003)

Detailed experimental methods are provided in the supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Protein backbone mutagenesis used to modify the ion binding sites in a K+ channel

Structures of K+ channels with amide-to-ester substitutions in the selectivity filter

Specific roles of the individual ion binding sites in C-type inactivation determined

A working model for changes at the selectivity filter during C-type inactivation

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. MacKinnon for providing the Fab-expressing hybridoma cells, Daniel Cawley for monoclonal antibody production and Dr. Michael Chapman and members of the Chapman group for answering our queries on X-ray crystallography. Part of this research was performed at the Advanced Light Source, which is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences Division, US Department of Energy, under contract no. DE-AC03-76SF00098, at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. This research was supported by a grant from the NIH (GM087546) to FIV.

Footnotes

Accession codes: Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes: 5EC1 (KcsA V76ester), 5EC2 (KcsA V76ester+G77dA), 5EBW (KcsA G77ester), 5EBL (KcsAT75G, conductive) and 5EBM (KcsA T75G, constricted).

Author Contributions: KM and FIV conceived the project and wrote the paper. AWA and FIV assembled the semisynthetic channels; KM performed the electrophysiological characterization, crystallization and structure determination; JCN carried out the X-ray data collection.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ader C, Schneider R, Hornig S, Velisetty P, Vardanyan V, Giller K, Ohmert I, Becker S, Pongs O, Baldus M. Coupling of activation and inactivation gate in a K+-channel: potassium and ligand sensitivity. EMBO J. 2009;28:2825–2834. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM, Hoshi T. K(+) channel gating: C-type inactivation is enhanced by calcium or lanthanum outside. J Gen Physiol. 2014;144:221–230. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201411223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berneche S, Roux B. A gate in the selectivity filter of potassium channels. Structure. 2005;13:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhate MP, McDermott AE. Protonation state of E71 in KcsA and its role for channel collapse and inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15265–15270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211900109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S, Cordero-Morales JF, Perozo E. A quantitative description of KcsA gating I: macroscopic currents. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:465–478. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary A, Raines RT. An evaluation of peptide-bond isosteres. Chembiochem. 2011;12:1801–1807. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JE, Srikumar D, Holmgren M. Gating at the selectivity filter in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3310–3314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709809105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Perozo E. Voltage-dependent gating at the KcsA selectivity filter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006a;13:319–322. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Zhao Y, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Roux B, Perozo E. Molecular determinants of gating at the potassium-channel selectivity filter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006b;13:311–318. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Jogini V, Chakrapani S, Perozo E. A multipoint hydrogen-bond network underlying KcsA C-type inactivation. Biophys J. 2011;100:2387–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Jogini V, Lewis A, Vasquez V, Cortes DM, Roux B, Perozo E. Molecular driving forces determining potassium channel slow inactivation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1062–1069. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Pan AC, Gagnon DG, Dalmas O, Cordero-Morales JF, Chakrapani S, Roux B, Perozo E. Structural basis for the coupling between activation and inactivation gates in K(+) channels. Nature. 2010a;466:272–275. doi: 10.1038/nature09136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Perozo E. Structural mechanism of C-type inactivation in K(+) channels. Nature. 2010b;466:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nature09153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello LG, Romero JG, Cortes DM, Perozo E. pH-dependent gating in the Streptomyces lividans K+ channel. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3229–3236. doi: 10.1021/bi972997x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB. Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraneni PK, Komarov AG, Costantino CA, Devereaux JJ, Matulef K, Valiyaveetil FI. Semisynthetic K+ channels show that the constricted conformation of the selectivity filter is not the C-type inactivated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:15698–15703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308699110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn GE, Zagotta WN. Conformational changes in S6 coupled to the opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 2001;30:689–698. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Mi X, Paajanen V, Wang K, Fan Z. Activation-coupled inactivation in the bacterial potassium channel KcsA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17630–17635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505158102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Armstrong CM. C-type inactivation of voltage-gated K+ channels: pore constriction or dilation? J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:151–160. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Two types of inactivation in Shaker K+ channels: effects of alterations in the carboxy-terminal region. Neuron. 1991;7:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, Osawa M, Takeuchi K, Shimada I. Structural basis underlying the dual gate properties of KcsA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6216–6221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911270107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature. 2002;417:523–526. doi: 10.1038/417523a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Ruta V, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 2003;423:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent SB. Chemical synthesis of peptides and proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:957–989. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarov AG, Linn KM, Devereaux JJ, Valiyaveetil FI. Modular strategy for the semisynthesis of a K+ channel: investigating interactions of the pore helix. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:1029–1038. doi: 10.1021/cb900210r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata HT, Fedida D. A structural interpretation of voltage-gated potassium channel inactivation. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:185–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson HP, Elinder F. A conserved glutamate is important for slow inactivation in K+ channels. Neuron. 2000;27:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Holmgren M, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 1997;19:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Dynamic rearrangement of the outer mouth of a K+ channel during gating. Neuron. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SB, Tao X, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots E, Isacoff EY. Protein rearrangements underlying slow inactivation of the Shaker K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:377–389. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R. Nobel Lecture. Potassium channels and the atomic basis of selective ion conduction. Biosci Rep. 2004;24:75–100. doi: 10.1007/s10540-004-7190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R, Cohen SL, Kuo A, Lee A, Chait BT. Structural conservation in prokaryotic and eukaryotic potassium channels. Science. 1998;280:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulef K, Komarov AG, Costantino CA, Valiyaveetil FI. Using protein backbone mutagenesis to dissect the link between ion occupancy and C-type inactivation in K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17886–17891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314356110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy JG, Nimigean CM. Structural correlates of selectivity and inactivation in potassium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral JH, Zhou Y, MacKinnon R. Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature. 2001;414:37–42. doi: 10.1038/35102000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir TW. Semisynthesis of proteins by expressed protein ligation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:249–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panyi G, Deutsch C. Cross talk between activation and slow inactivation gates of Shaker potassium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:547–559. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo E, Cortes DM, Cuello LG. Structural rearrangements underlying K+-channel activation gating. Science. 1999;285:73–78. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechotta PL, Rapedius M, Stansfeld PJ, Bollepalli MK, Ehrlich G, Andres-Enguix I, Fritzenschaft H, Decher N, Sansom MS, Tucker SJ, et al. The pore structure and gating mechanism of K2P channels. EMBO J. 2011;30:3607–3619. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskorowski RA, Aldrich RW. Relationship between pore occupancy and gating in BK potassium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:557–576. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pless SA, Galpin JD, Niciforovic AP, Kurata HT, Ahern CA. Hydrogen bonds as molecular timers for slow inactivation in voltage-gated potassium channels. Elife. 2013;2:e01289. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers ET, Deechongkit S, Kelly JW. Backbone-Backbone H-Bonds Make Context-Dependent Contributions to Protein Folding Kinetics and Thermodynamics: Lessons from Amide-to-Ester Mutations. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;72:39–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)72002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman H, Islam SM, Mukherjee S, Roux B, Perozo E. Dynamics transitions at the outer vestibule of the KcsA potassium channel during gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1831–1836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314875111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray EC, Deutsch C. A trapped intracellular cation modulates K+ channel recovery from slow inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:203–217. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X, Avalos JL, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 A resolution. Science. 2009;326:1668–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.1180310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Begenisich T. Selectivity filter gating in large-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2012;139:235–244. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth B, Csanady L. Pore collapse underlies irreversible inactivation of TRPM2 cation channel currents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13440–13445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204702109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twibanire JD, Grindley TB. Efficient and controllably selective preparation of esters using uronium-based coupling agents. Org Lett. 2011;13:2988–2991. doi: 10.1021/ol201005s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiyaveetil FI, Leonetti M, Muir TW, Mackinnon R. Ion selectivity in a semisynthetic K+ channel locked in the conductive conformation. Science. 2006a;314:1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1133415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiyaveetil FI, Sekedat M, MacKinnon R, Muir TW. Structural and functional consequences of an amide-to-ester substitution in the selectivity filter of a potassium channel. J Am Chem Soc. 2006b;128:11591–11599. doi: 10.1021/ja0631955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiyaveetil FI, Sekedat M, Muir TW, MacKinnon R. Semisynthesis of a functional K+ channel. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:2504–2507. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G. Keeping K+ completely comfortable. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:1011–1013. doi: 10.1038/nsb1201-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, MacKinnon R. A mutant KcsA K(+) channel with altered conduction properties and selectivity filter ion distribution. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, MacKinnon R. The occupancy of ions in the K+ selectivity filter: charge balance and coupling of ion binding to a protein conformational change underlie high conduction rates. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 Å resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.