Abstract

Most gallbladder cancer (GBC) cases arise in the context of gallstones, which cause inflammation, but few gallstone patients develop GBC. We explored inflammation/immune-related markers measured in bile and serum in GBC cases compared to gallstone patients to better understand how inflammatory patterns in these two conditions differ. We measured 65 immune-related markers in serum and bile from 41 GBC cases and 127 gallstone patients from Shanghai, China, and calculated age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for GBC versus gallstones. We then focused on the markers that were significantly elevated in bile and serum to replicate in serum from 35 GBC cases and 31 gallstone controls from Chile. Comparing the highest versus lowest quantile, 15 markers (23%) were elevated in both serum and bile from GBC versus gallstone patients in the Shanghai study (p<0.05). The strongest OR was for CXCL8 (interleukin-8) in serum (96.8, 95% CI: 11.9–790.2). Of these 15 markers, 6 were also significantly elevated in serum from Chile (CCL20, C-reactive protein, CXCL8, CXCL10, resistin, serum amyloid A). Pooled ORs from Shanghai and Chile for these 6 markers ranged from 7.2 (95% CI: 2.8–18.4) for CXCL10 to 58.2 (95% CI: 12.4–273.0) for CXCL8. GBC is associated with inflammation above and beyond that generated by gallstones alone. This local inflammatory process is reflected systemically. Future longitudinal studies are needed to identify the key players in cancer development, which may guide translational efforts to identify individuals at high risk of developing GBC.

Keywords: local inflammation, systemic inflammation, gallbladder cancer

1. Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC), the most common type of biliary tract cancer [1, 2], is highly fatal, with an overall median survival rate of 3–7 months [3, 4]. Gallstones are the central risk factor for GBC and create extensive inflammation in the gallbladder [5]. Other proposed risk factors also likely act through inflammatory pathways. For example, infections (e.g., Helicobacter species), obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other inflammation-related conditions have been associated with increased risk of GBC [6–11], while aspirin use has been associated with decreased risk [1, 12]. In addition, single nucleotide polymorphisms in inflammatory-related genes have been associated with GBC [13–15].

Taken together, these data suggest that inflammation is an essential component in gallbladder carcinogenesis. Despite the fact that gallstones are present in 90% or more of GBC patients [16], however, only a small fraction (0.3–3%) of gallstone patients develop GBC [16]. We hypothesized that gallstone patients who develop GBC may have a different inflammatory response than those who do not and that therefore GBC patients will have increased levels of immune and inflammatory markers both locally and systemically when compared to GS patients.

Some studies have assessed inflammation markers and GBC prognosis [15, 17, 18], but few studies have evaluated immune-related markers locally in bile [19]. Even fewer have evaluated inflammation markers and GBC incidence by comparing GBC cases to controls. Those studies that have done so were generally quite small and evaluated only a few markers [20, 21]. We recently demonstrated that multiplexed assays can be used to measure inflammation markers in bile [19] and serum [22], providing information about both local and systemic inflammation.

Therefore, we undertook a study to compare inflammation markers in GBC and gallstone patients. We first evaluated bile and serum from the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Study so that we could compare the inflammatory profile both locally (using bile) and systemically (using serum). Focusing on the markers that were significantly associated with GBC compared to gallstones in both bile and serum from the Shanghai study, we then verified the findings using serum samples from the Chile Gallbladder Cancer Study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study population and samples

In brief, the Shanghai Biliary Cancer Study enrolled 368 GBC cases who were permanent residents of urban Shanghai and 774 GS patients frequency matched on to cancer cases age, sex, and hospital [23]. Patients newly diagnosed with primary biliary tract cancer (ICD9 156) from June 1997 through May 2001 were identified through a rapid-reporting system established between the Shanghai Cancer Institute and 42 collaborating hospitals in 10 urban districts of Shanghai [23]. Gallstone patients were recruited from patients undergoing cholecystectomy or medical treatment at the same hospital as the index case and frequency matched by gender and age. Individuals with a previous history of non-skin cancer were excluded as their risk of developing GBC may differ from that of the general population. Over 90% of eligible GBC cases and over 95% of eligible stone cases participated. The Shanghai Cancer Institute and National Cancer Institute institutional review boards approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent for biospecimen and questionnaire data collection.

The Chile Gallbladder Cancer Study enrolled 52 GBC cases and 37 gallstone patients from April 2012 through August 2013. Participants had to be previously cancer-free and covered by public health insurance (>90% of population). We recruited incident GBC cases identified through rapid ascertainment at cancer referral hospitals in Santiago, Concepción, and Temuco, focusing on surgical cases to allow for tissue collection. We aimed at 1:1 matching of gallstone controls by age, sex, and hospital, but pairing was limited by the small number of gallstone patients over age 50 who underwent surgery. Participation rates were similar for cases (85%) and gallstone patients (86%). Written consent was obtained for biospecimen and questionnaire data collection. The National Cancer Institute, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, and Chilean Ministry of Health institutional review boards approved the study.

For the current analysis, we included all GBC cases with bile available (N=44) and 134 (~3:1) randomly selected gallstone patients with bile available from the Shanghai study; 41 GBC cases and 127 gallstone controls also had paired serum samples. Bile samples were aspirated under sterile conditions directly from the gallbladder using a syringe. From the Chile study, we included serum samples from 35 GBC cases and 31 gallstone patients (essentially all available). In the Chile study, 79% of gallbladder cancer cases (27/34) and 75% of gallstone controls (21/28) reported intense abdominal pain/colic (χ2 p-value = 0.7), and in the Shanghai study, 57% (16/28) of cases and 57% of controls (73/127) reported biliary pain (χ2 p-value = 1.0). In the Shanghai and Chile studies combined, blood was collected prior to surgery for 189/234 participants with data on timing of blood collection (81%) and was fasting for 82% (192/234). Samples were stored at −70°C.

2.2 Laboratory assays

In a recent bile methods study we found that the Milliplex assay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which has been shown to perform reliably in serum [22], performed well for most, but not all markers in bile (see Supplementary Table 2 in Kemp et al) [19]. The Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) Human Vascular Injury II kit (Meso Scale Diagnostics LLC, Rockville, MD, USA) performed better for the measurement of acute phase markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) in bile [19]. Therefore, we used the Milliplex assay to measure 61 markers and the MSD assay to measure 4 acute-phase markers [CRP, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), serum amyloid A (SAA), vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1)] in serum and in bile.

For the Milliplex assay, the beads were added to 96-well plates and incubated with the test samples. After incubation, fluorescently labeled detection antibodies were added. The 96-well plates were then analyzed using a modified flow cytometer (Bio-Plex 200, Bio-Rad). Data were reported as pg/ml using Bio-Plex Manager 6.1 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Seven markers (Flt3L, MCP3, sCD30, sCD40L, SIL1RI, sRAGE and sVEGFR1) were measured in the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Study but were not measured in the Chile study, having been removed from the Milliplex platform due to poor performance.

The MSD plate-based ELISA assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, bile and serum samples were incubated with assay diluent, followed by incubation with a detection antibody. The MSD plates were then analyzed using the MSD Sector Imager 6000 plate reader and Discovery Workbench 3.0 software (Meso Scale Diagnostics LLC, Rockville, MD, USA).

As determined by earlier optimization procedures [19], the bile samples were diluted 1:10 in assay buffer for the Milliplex Cytokine 1 (19-plex), Cytokine 2 (17-plex), and Cytokine 3 (7-plex) panels; 1:40 for the Milliplex Soluble Receptor Panel (13-plex); and 1:100 for the Milliplex Adipokine Panel 1 (5-plex) and the MSD panel (Vascular Injury Panel 2, 4-plex). Bile samples were not normalized since we previously found that normalization using total protein (BCA) or albumin increased laboratory variation [as indicated by increased coefficients of variation (CVs)] without improving the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) [19]. All samples were tested in duplicate. Analyses were based on an average of the duplicate measures.

Each 96-well plate included blinded samples from GBC and gallstone patients, matched by study. In addition, we included blinded duplicates of bile and serum samples from 10 gallstone patients in the Shanghai study to evaluate assay reproducibility through CVs and ICCs calculated on log-transformed values. (Untransformed CV values also presented in Supplemental Table 1.) Of markers with >25% detectability, ICCs were >0.8 for 42/60 (70%) markers measured in bile and 49/54 (91%) markers in serum, indicating high reproducibility for a majority of markers (Supplemental Table 1). The markers had somewhat better reproducibility (higher ICCs and lower CVs) in serum than in bile.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of GBC and gallstone patients were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Inflammation markers were analyzed as categorical, continuous (log-transformed), and dichotomous (above or below the lower limit of detection) variables. Measurements below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) were assigned a value of ½ the LLOQ, and measurements above the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) were assigned the ULOQ value. Marker categories were determined based on the proportion of subjects with detectable values as follows: a) for markers detectable in ≥ 75% of subjects, four categories were created based on quartiles of values above the LLOQ (subjects with undetectable values were included in the lowest quartile); b) for markers detectable in 50–75% of subjects, four categories were created where the first category included all subjects with undetectable values and the next three categories were based on tertiles of values above the LLOQ; c) for markers detectable in 25–50% of subjects, three categories were created where the first category included all subjects with undetectable values and the next two categories were based on a median split of the values above the LLOQ; d) for markers detectable in <25% of subjects, two categories were created: one for undetectable values and the other for values above the LLOQ.

We evaluated correlations of continuous marker levels in bile and serum samples from the Shanghai study for GBC and gallstone patients separately. For each group, we computed Spearman rank correlations between marker levels in the two specimen types for those markers that were detectable in 25% or more of both bile and serum specimens using two methods: 1) using all values (with measurements outside the LOQ assigned as above) and 2) restricted to values within the LOQ. We also used stepwise linear regression models fit to values above the LLOQ to determine whether serum or bile inflammation marker levels in gallstone patients were associated with the following variables: age (<55, 55–64, ≥ 65), sex (male/female), years of education (continuous), ever drinking (yes/no), ever smoking (yes/no), categorical BMI (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese), hypertension (yes/no), waist to hip ratio (continuous), diabetes (yes/no), fasting status (fasting/not fasting), kidney or bladder infection (yes/no), positive aerobic bile culture (yes/no), tuberculosis (yes/no), Helicobacter pylori seropositivity(yes/no), chronic gastritis (yes/no), gastric ulcer (yes/no), duodenal ulcer (yes/no), appendicitis (yes/no), and gallstone type (non-cholesterol versus cholesterol), number (ordinal tertiles), largest size (ordinal tertiles), and weight (ordinal tertiles). Given the number of covariates and inflammation markers, we required p<0.05 for a variable to be entered into a model and p<0.01 for that variable to be retained in the model. Using unconditional logistic regression, we then examined the impact of the covariate on the odds ratios (ORs) for the association between the categorical inflammation marker and GBC while adjusting for age and gender. Covariates that changed the OR for a given inflammation marker by more than 10% were retained in the model for that marker.

Based on these model-building exercises in the Shanghai study, we evaluated the associations between individual inflammation markers and GBC risk adjusting for age and gender, as well as additional variables as appropriate for a given inflammation marker, using measurements from 1) bile or serum from Shanghai only, 2) serum from Chile only, and 3) serum from Shanghai and Chile combined. We present the results for categorical variables from unconditional models since using conditional logistic regression models for Chile (supplemental table 2) or evaluating the inflammation markers as continuous or dichotomous variables (data not shown) did not qualitatively change the findings. All Chile models were also adjusted for study site. The primary analyses for Shanghai and Chile combined involved pooling the two datasets, using study-specific immune marker categories and controlling for study/site, age, and gender. However, we also combined study-specific results using a fixed effects meta-analysis and examined Cochrane’s Q for heterogeneity. Heterogeneity p-values were >0.05 for all markers except sGP130 (p=0.04), sIL-1RII (P=0.003), and TARC (P=0.03). Meta-analysis-based ORs were similar to those using a pooled dataset (data not shown). Two-sided P-values for trend across marker categories were evaluated with the Wald test using marker levels as an ordinal variable with 1 degree of freedom. To adjust for multiple testing, we applied a Bonferroni correction to the pooled study findings, considering p<0.0008 significant (0.05/65 markers).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to assess whether systematic, non-biological biases might account for the results, including restricting to patients with open surgery, early stage cases (i.e., resectable, local, stages 1 and 2; N=15) versus controls, pre-surgery blood collection or no surgery (for two cases from Chile), and individuals with gallstones. We also used polytomous regression models to assess early versus late (i.e., unresectable, regional/distant, stages 3+) stage cancers versus gallstones and marker levels split at the median due to small sample sizes.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive characteristics

In both Shanghai and Chile, GBC and gallstone patients had a similar distribution of sociodemographic, behavioral, and medical characteristics (Table 1). In the Shanghai study, all but five markers (SCF, SIL-1RI, SVEGFR3, TPO, and TSLP) were detectable in more than 25% of bile samples, and all but 12 markers (Flt3L, IFNa2, IL11, IL12p40, IL33, LIF, MCP3, MCP4, SCD30, SIL-1RI, sRAGE, and TSLP) were detectable in more than 25% of serum samples (Table 2). The results for serum were similar in Chile; only fractalkine, IFNa2, IL12p40, IL33, LIF and TSLP were detectable in fewer than 25% of serum samples from Chile (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of gallbladder cancer cases (GBC) and gallstone patients (GS) with multiplexed immune marker data from the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Case-Control Study and the Chile Gallbladder Cancer Study.

| Characteristic | Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Case-Control Study

|

Chile Gallbladder Cancer Study

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBC (n=44)

|

GS (n=134)

|

p-value* | GBC (n=35)

|

GS (n=31)

|

p-value* | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Gender | 0.70 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Male | 11 | 25.0 | 38 | 28.4 | 7 | 20.0 | 7 | 22.6 | ||

| Female | 33 | 75.0 | 96 | 71.6 | 28 | 80.0 | 24 | 77.4 | ||

| Age | 0.83 | |||||||||

| <=54 | 5 | 11.4 | 20 | 14.9 | 10 | 28.6 | 13 | 41.9 | 0.40 | |

| 55–65 | 14 | 31.8 | 39 | 29.1 | 11 | 31.4 | 6 | 19.4 | ||

| >=66 | 25 | 56.8 | 75 | 56.0 | 14 | 40.0 | 12 | 38.7 | ||

| Education | 0.39 | 0.65 | ||||||||

| None/Primary | 17 | 38.6 | 49 | 36.6 | 19 | 54.3 | 13 | 43.3 | ||

| Jr. Middle | 12 | 27.3 | 30 | 22.4 | 9 | 25.7 | 7 | 23.3 | ||

| Sr. Middle | 6 | 13.6 | 34 | 25.4 | 5 | 14.3 | 6 | 20.0 | ||

| Some college | 9 | 20.5 | 21 | 15.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 4 | 13.3 | ||

| Ever smoker | 0.84 | 0.21 | ||||||||

| no | 35 | 79.5 | 103 | 76.9 | 24 | 68.6 | 16 | 51.6 | ||

| yes | 9 | 20.5 | 31 | 23.1 | 11 | 31.4 | 15 | 48.4 | ||

| Ever drinker | 1.00 | 0.40 | ||||||||

| no | 36 | 81.8 | 111 | 82.8 | 17 | 60.7 | 11 | 45.8 | ||

| yes | 8 | 18.2 | 23 | 17.2 | 11 | 39.3 | 13 | 54.2 | ||

| Self-reported past body mass index | † | 0.24 | 0.49 | |||||||

| Underweight: <18.5 | 2 | 4.5 | 7 | 5.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Normal: 18.5–24.9 | 22 | 50.0 | 86 | 64.2 | 14 | 46.7 | 9 | 34.6 | ||

| Overweight: 25–29.9 | 19 | 43.2 | 36 | 26.9 | 8 | 26.7 | 11 | 42.3 | ||

| Obese: >=30.0 | 1 | 2.3 | 5 | 3.7 | 8 | 26.7 | 6 | 23.1 | ||

| Self-reported diabetes | 0.45 | 0.57 | ||||||||

| no | 40 | 90.9 | 114 | 85.1 | 26 | 74.3 | 25 | 80.6 | ||

| yes | 4 | 9.1 | 20 | 14.9 | 9 | 25.7 | 6 | 19.4 | ||

Fisher’s exact test p-value

Self-reported BMI 5 years prior to interview (Shanghai), 3 years prior to interview (Chile), or usual adult weight (Chile)

Table 2.

Detection of immune markers measured in bile and serum from GBC and GS patients in the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Study and serum in the Chile study, as well as correlation between immune markers measured in bile and serum (Shanghai).

| % detectable*

|

Bile/serum correlations†

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai

|

Chile Serum (N=66) | GBC patients

|

GS patients

|

||||

| Bile (N=178) | Serum (N=168) | Coeff. | P-value | Coeff. | P-value | ||

| Adiponectin | 98.9 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| Adipsin | 98.9 | 99.4 | 100.0 | −0.11 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| CCL11 | 79.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.07 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| CCL2 | 97.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.27 | 0.003 |

| CCL4 | 91.0 | 97.6 | 90.9 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.69 |

| CCL8 | 78.7 | 98.8 | 100.0 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.233 |

| CCL7 | 73.6 | 20.2 | -- | 0.20 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.77 |

| CCL13 | 62.4 | 20.8 | 62.1 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.54 |

| CCL15 | 97.8 | 98.8 | 100.0 | 0.22 | 0.18 | −0.15 | 0.09 |

| CCL17 | 94.4 | 100.0 | 98.5 | −0.14 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.64 |

| CCL19 | 75.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| CCL20 | 88.2 | 85.7 | 93.9 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.32 | 0.0003 |

| CCL21 | 94.4 | 60.1 | 84.9 | −0.05 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 0.50 |

| CCL22 | 87.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.19 | 0.24 | −0.12 | 0.18 |

| CCL24 | 93.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.39 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.92 |

| CCL27 | 78.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| CRP | 99.4 | 98.2 | 68.2 | 0.69 | <.0001 | 0.46 | <.0001 |

| CXCL1,2,3 | 89.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.06 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.88 |

| CXCL5 | 90.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.48 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.85 |

| CXCL6 | 88.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.64 |

| CXCL8 (IL8) | 92.7 | 99.4 | 100.0 | −0.07 | 0.68 | 0.23 | 0.009 |

| CXCL9 | 92.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.46 | 0.003 | 0.23 | 0.009 |

| CXCL10 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.002 |

| CXCL11 | 75.8 | 99.4 | 100.0 | −0.02 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.80 |

| CXCL12 | 88.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.04 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| CXCL13 | 83.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.06 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| CX3CL1 | 89.9 | 39.9 | 19.7 | 0.11 | 0.49 | −0.25 | 0.006 |

| EGF | 100.0 | 86.3 | 83.3 | 0.10 | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.53 |

| FGF2 | 94.4 | 50.6 | 27.3 | 0.06 | 0.71 | −0.16 | 0.08 |

| Flt3L | 31.5 | 13.7 | -- | 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.45 |

| GCSF | 91.6 | 72.0 | 53.0 | −0.03 | 0.83 | −0.04 | 0.65 |

| ICAM-1 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.15 | 0.10 |

| IFNa2 | 73.6 | 8.9 | 13.6 | −0.04 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.65 |

| IFNg | 89.9 | 59.5 | 33.3 | 0.003 | 0.99 | −0.05 | 0.59 |

| IL11 | 87.6 | 2.4 | 31.8 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.39 |

| IL12p40 | 48.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | −0.05 | 0.76 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| IL16 | 58.4 | 63.1 | 83.3 | −0.08 | 0.61 | −0.08 | 0.37 |

| IL29 | 81.5 | 27.4 | 30.3 | −0.02 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 0.31 |

| IL33 | 48.9 | 22.6 | 19.7 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.39 |

| LIF | 99.4 | ND | 3.0 | ||||

| Lipocalin2 | 98.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| PAI1 | 96.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.06 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| Resistin | 97.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| SAA | 84.3 | 93.5 | 66.7 | 0.55 | 0.0002 | 0.39 | <.0001 |

| SCD30 | 26.6 | 7.3 | -- | 0.08 | 0.6326 | −0.05 | 0.62 |

| sCD40L | 91.6 | 34.5 | -- | −0.11 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.45 |

| SCF | 2.8 | 54.8 | 31.8 | −0.12 | 0.45 | −0.07 | 0.44 |

| SEGFR | 56.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.14 | 0.39 | −0.14 | 0.13 |

| SGP130 | 96.0 | 99.4 | 98.5 | −0.07 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| SIL1RI | 8.1 | 0.6 | -- | ||||

| SIL4R | 43.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.12 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.29 |

| SIL6R | 76.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.38 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.67 |

| SILRII | 68.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.09 | 0.60 | −0.04 | 0.66 |

| SRAGE | 18.5 | 15.2 | -- | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.61 |

| STNFRII | 79.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.14 | 0.14 |

| STNFRI | 87.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | −0.06 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.35 |

| SVEGFR1 | 71.7 | 73.2 | -- | −0.18 | 0.27 | −0.04 | 0.66 |

| SVEGFR2 | 31.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.57 |

| SVEGFR3 | 15.6 | 95.7 | 97.0 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| TARC | 87.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.25 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.84 |

| TPO | 2.8 | 86.3 | 78.8 | ||||

| TRAIL | 87.6 | 99.4 | 100.0 | −0.01 | 0.94 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| TSLP | 22.5 | 14.9 | 13.6 | 0.05 | 0.59 | ||

| VCAM-1 | 91.0 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| VEGF | 92.7 | 74.4 | 50.0 | 0.32 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.64 |

Percent above lower limit of quantification (LLOQ)

Based on all values for markers with ≥ 25% detectability in both bile and serum and adjusted for hemoglobin detected in the bile.

Notes: ND=not detected; --=not part of the assay for the Chile study

3.2 Correlation between inflammation markers measured in bile and serum

In the Shanghai study, 50 markers were detectable in at least 25% of both serum and bile samples. Among these 50, 16 (32%) were significantly correlated (p<0.05) between bile and serum in GBC cases and/or gallstone patients using all measurement values (including ½ the LLOQ if a marker was not detectable in a given sample) (Table 2). Of these, 3 (CCL20, CRP, and SAA) passed multiple comparisons testing (p<0.005), and all were positively correlated. CRP, CXCL9, ENA78, and SAA had correlations >0.4. Results were similar using only values measured within the LOD; 15 markers had significant correlations, all were positively correlated, and CRP, CXCL9, EGF, ENA73, IL29/IFNl1, and SAA had correlations >0.4 (data not shown). Overall agreement of detectability in bile and serum was ≥ 70% for 36 of 50 (72%) markers.

3.3 Multivariable model building

Sixteen covariates were associated with one or more inflammation markers among gallstone patients from Shanghai (data not shown). However, only a few changed the association between the bile or serum inflammation marker and GBC compared to gallstones by >10%. In bile these covariates included gender for IL29/IFNl1, appendicitis for TARC, positive aerobic culture for CCL20 and sTNFRI, TB for ENA78, number of gallstones for sIL-1RII, size of largest gallstone for GRO, and weight of gallstones for adiponectin. In serum these covariates included age for CXCL11 and TSLP, gender for CCL20 and ENA78, and BMI for GCSF, IFNA2, and sIL-1RII. We adjusted all models for age and gender as matching variables and for additional covariates as appropriate.

3.4 Associations between inflammation markers and GBC versus gallstones

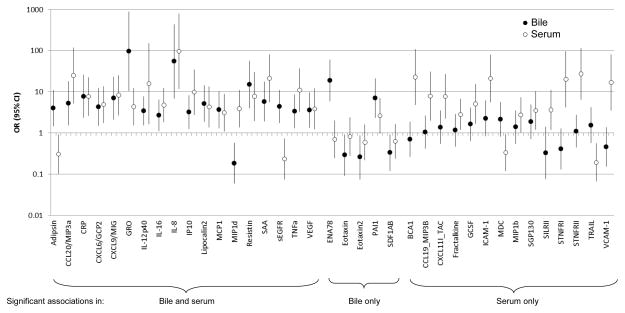

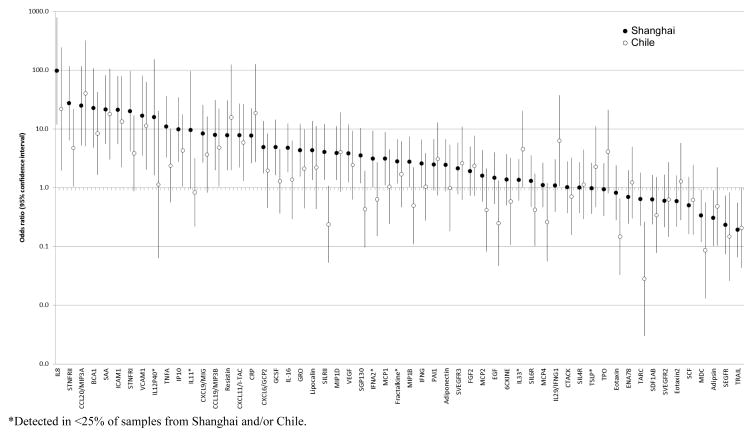

We first examined the associations of bile and serum immune markers with GBC in the Shanghai study. Comparing the highest to the lowest marker level category (as determined by proportion detectable—see Methods), 18 markers were significantly (p<0.05) associated with GBC versus gallstone when measured in both bile and serum, 5 were significantly associated in bile only, and 14 were significantly associated in serum only (Figure 1). Of the 18 markers significantly associated in both bile and serum, 15 were higher in GBC cases compared to gallstone patients both in bile and serum. Of these 15, 6 (CCL20, CRP, CXCL8, CXCL10, resistin, SAA) were also significantly elevated in serum samples from Chile (Table 3), where the pattern of associations was similar to that observed in Shanghai (Figure 2). Combining the serum measurements from Shanghai and Chile, the associations of these 6 markers with GBC versus gallstones ranged from 7.2 (95% CI: 2.8–18.4) for CXCL10 to 96.8 (95% CI: 11.9–790.2) for CXCL8. All 6 markers had p-trend values <0.0001 and passed Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The associations remained elevated when restricted to open surgery, early stage cancers, and pre-surgery or no surgery blood collection (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Association of high versus low immune-related marker category in bile (black circles) and serum (white circles) from gallbladder cancer cases compared to gallstone patients in the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Case-control Study.

Table 3.

Markers robustly associated with gallbladder cancer versus gallstones in both the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Study and the Chile Gallbladder Cancer Study.

| Marker | Shanghai

|

Chile

|

Shanghai & Chile Combined

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile ORs (95% CIs)* | Serum ORs (95% CIs)* | Serum ORs (95% CIs)* | Serum ORs (95% CIs)* | Serum ORs (95% CIs)* restricted to:

|

|||

| Open surgery | Early stage | Pre/no surgery collection | |||||

| CCL20† | |||||||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 0.6 (0.2–2.3) | 3.4 (0.6–18.0) | 2.7 (0.4–16.8) | 3.1 (0.9–10.2) | 5.9 (0.6–57.5) | ND | 4.3 (0.8–187.9) |

| Q3 | 1.8 (0.6–5.7) | 6.7 (1.3–33.4) | 3.8 (0.6–22.2) | 5.0 (1.6–15.8) | 5.7 (0.6–59.4) | ND | 7.1 (1.4–35.7) |

| Q4 | 5.3 (1.5–18.2) | 24.8 (5.3–117.2) | 40.4 (5.1–319.1) | 24.5 (7.9–76.1) | 34.8 (3.8–320.1) | ND | 37.4 (7.4–187.9) |

| p-trend‡ | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| CRP | |||||||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 3.2 (0.9–11.2) | 0.4 (0.1–1.8) | 1.0 (0.2–5.1) | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.4 (0.1–2.9) | 0.4 (0.1–2.4) | 0.6 (0.2–2.3) |

| Q3 | 2.4 (0.7–8.5) | 1.3 (0.4–4.3) | 2.0 (0.4–11.5) | 1.6 (0.6–4.2) | 1.3 (0.3–6.7) | 0.6 (0.1–3.1) | 2.2 (0.7–7.0) |

| Q4 | 7.7 (2.3–25.5) | 7.6 (2.6–22.3) | 18.6 (2.7–125.7) | 9.4 (3.7–23.9) | 9.2 (2.1–39.6) | 2.5 (0.6–10.5) | 11.2 (3.6–35.0) |

| p-trend‡ | 0.001 | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | |||||||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 2.0 (0.2–23.3) | 4.2 (0.5–39.7) | 6.0 (0.5–69.5) | 4.9 (0.98–24.2) | 1.7 (0.3–11.7) | ND | 4.9 (0.5–47.0) |

| Q3 | 26.9 (3.3–216.3) | 9.1 (1.1–78.8) | 10.3 (0.9–114.7) | 9.2 (1.9–43.3) | 0.8 (0.1–9.4) | ND | 12.8 (1.5–106.2) |

| Q4 | 54.7 (6.9–432.7) | 96.8 (11.9–790.2) | 21.9 (2.0–243.9) | 58.2 (12.4–273.0) | 35.2 (6.4–193.5) | ND | 109.6 (12.9–933.2) |

| p-trend‡ | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.006 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| CXCL10 | |||||||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 0.8 (0.3–2.3) | 0.8 (0.2–3.9) | 2.2 (0.5–9.7) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | 0.9 (0.2–5.0) | 3.2 (0.3–34.1) | 3.4 (0.6–18.3) |

| Q3 | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) | 5.8 (1.7–19.9) | 5.0 (1.0–24.8) | 5.3 (2.1–13.7) | 3.6 (0.8–16.2) | 9.4 (1.0–88.5) | 16.6 (3.4–81.1) |

| Q4 | 3.2 (1.2–8.3) | 9.8 (2.8–34.4) | 4.3 (1.0–17.7) | 7.2 (2.8–18.4) | 8.2 (1.8–37.9) | 6.4 (0.6–66.5) | 15.7 (3.1–78.8) |

| p-trend‡ | 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.06 | <0.0001 |

| RESISTIN | |||||||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 3.6 (0.9–14.6) | 4.1 (1.0–16.3) | 4.2 (0.6–27.7) | 4.2 (1.4–12.5) | 4.4 (0.4–46.6) | 3.5 (0.3–36.0) | 6.3 (1.3–30.8) |

| Q3 | 3.5 (0.9–14.1) | 7.0 (1.8–27.3) | 3.0 (0.5–19.3) | 5.1 (1.7–15.4) | 14.7 (1.6–134.1) | 10.0 (1.1–87.8) | 11.2 (2.3–53.2) |

| Q4 | 15.0 (4.0–56.2) | 7.8 (2.0–30.4) | 15.7 (2.0–125.0) | 9.2 (3.0–27.8) | 24.2 (2.7–213.5) | 6.1 (0.6–59.1) | 12.5 (2.6–60.8) |

| p-trend‡ | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.05 | <0.0001 |

| SAA | |||||||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 1.7 (0.5–5.8) | 2.6 (0.6–10.8) | 1.7 (0.3–8.5) | 2.3 (0.8–6.5) | 0.8 (0.1–6.4) | 1.4 (0.3–6.8) | 1.2 (0.4–4.1) |

| Q3 | 2.9 (0.9–9.2) | 1.6 (0.4–7.4) | 5.9 (0.99–34.8) | 2.4 (0.8–7.2) | 3.3 (0.6–19.9) | 0.3 (0.03–3.0) | 1.8 (0.5–6.4) |

| Q4 | 5.8 (1.9–17.5) | 21.3 (5.6–81.1) | 17.9 (3.0–105.4) | 19.3 (6.9–54.3) | 19.6 (3.5–109.6) | 5.3 (1.2–23.6) | 20.3 (6.2–66.5) |

| p-trend‡ | 0.0006 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.08 | <0.0001 |

Adjusted for age and gender

OR for bile also adjusted for positive aerobic culture

Two-sided P-values for trend across marker categories were evaluated with the Wald test using marker levels as an ordinal variable with 1 degree of freedom.

Notes: ND=not determined

Figure 2.

Association of high versus low circulating immune-related marker category with gallbladder cancer versus gallstones in the Shanghai Biliary Tract Cancer Case-control Study (black circles) and the Chile Gallbladder Cancer Study (white circles).

Twenty-six additional markers had p-trend values <0.05 after combining serum measurements from Shanghai and Chile (Supplemental table 3). Of these, 4 markers had ORs>10, 7 markers had ORs between 5–10 or 0.1–0.2, and 8 markers had ORs between 3–5 or 0.2–0.33. Eleven of these 26 associations passed Bonferroni correction: CXCL13, CCL19, CXCL11, CXCL9, ICAM-1, CCL22, sTNF-RI, sTNF-RII, TNFa, TRAIL, and VCAM-1 (supplemental table 3). Many associations remained elevated when restricted to open surgery and pre-surgery or no surgery blood collection (supplemental table 4) or when assessed by stage (supplemental table 5). Associations were also similar or slightly elevated when restricted to individuals with gallstones (supplemental table 6).

4. Discussion

We evaluated a large number of inflammatory markers and their association with GBC compared to gallstones. We found that CCL20, CRP, CXCL8, CXCL10, resistin, and SAA had particularly robust associations in that 1) the marker levels were highly elevated in GBC versus gallstones both when measured in bile and in serum, 2) the serum associations were strong and consistent in two independent study populations (Shanghai and Chile), and 3) the serum associations survived multiple comparisons testing and remained elevated in sensitivity analyses. Given the magnitude of the serum ORs from Shanghai and Chile combined [7.2 (95% CI: 2.8–18.4) for CXCL10 to 96.8 (95% CI: 11.9–790.2) for CXCL8], these 6 markers represent important targets for future studies on GBC etiology, early detection, and prevention.

Cytokine levels are generally low in healthy individuals without known gallbladder disease [24]. Recruitment of inflammatory cells is expected in the context of gallstones, but the associations we observed were for GBC compared to gallstones, therefore reflecting inflammatory processes beyond those elicited by gallstones alone. In addition, CXCL8, SAA, and CRP have been shown to be elevated many years prior to diagnosis of several cancers [16, 25, 26], suggesting that these markers may be etiologically relevant. Associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in IL-8 [15] and IL-8 receptor [14] provide additional support for the potential etiologic importance of CXCL8 in gallbladder carcinogenesis. CCL20, CXCL8, CXCL10, and SAA are chemoattractants for lymphocytes, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and/or monocytes [27, 28]. Chemokines often work through the same pathways. For example, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 all bind to CXC chemokine receptor-3 (CXCR3) to recruit inflammatory cells and facilitate Th1-mediated immune responses [29, 30]. Similarly, CCL2 and CXCL8 interact synergistically to maximize leukocyte chemotaxis [31], and a recent study found that SAA1 induces a chemotactic cascade, of which CXCL8 is part, leading to prolonged leukocyte attraction [32]. SAA also leads to prolonged expression of CCL20 [33].

The associations we observed with these markers suggest that these chemokine systems may be important to gallbladder carcinogenesis and should be interrogated through mechanistic studies. As recently described, such mechanistic characterization could help identify targets for treatment, but to date, little work has been done on GBC [34]. Thus, the results of this study offer timely clues into the role of chemokines in the pathogenesis of GBC.

Although the associations of bile and serum inflammation markers with GBC were generally similar, only about a third of the markers were significantly correlated in bile and serum, and most had r<0.4. There are several possible explanations for the relatively weak correlation between inflammation markers measured in bile and serum. Circulating markers originate from various sources and cells throughout the body, and systemic immune response may be amplified or dampened relative to local environments as an effect of positive or negative feedback loops. Other sources could also impact the correlation, such as differences in sampling and assay performance. For example, most blood samples were collected prior to surgery, while bile is collected at the time of surgery. Misclassification due to differences in the concentration of bile collected and lack of effective normalization methods or differences in assay performance by specimen type could also contribute. Markers measured in serum tended to have higher ICCs and lower CVs than those measured in bile. The complex nature of bile results in difficulty measuring biomarkers in bile, which may have contributed to poorer assay performance. Poor assay performance introduces misclassification, which may have affected the correlation between bile and serum. Given that the associations were often similar for inflammation markers measured in bile and serum, serum measurements seem reasonable to use in future studies, particularly given the challenges of using bile.

As with any case-control study, some associations could be driven by disease effects (i.e., that the associations with inflammation markers may be due to the presence of cancer rather than an etiologic role of these markers in the development of GBC). Although sensitivity analyses by stage suggest that many of these associations are not due entirely to disease effects since they remained elevated even for early-stage disease, ultimately longitudinal studies are needed. Longitudinal studies would also remove the limitation of self-reported variables, such as BMI and diabetes, which could lead to misclassification. The estimates are imprecise due to the small number of cases, especially with respect to early stage cancers, and we were unable to assess differences between serum and bile or between Shanghai and Chile using global statistics due to lack of power. Given the large number of multiple comparisons, some associations may be due to chance alone, although many of the associations between high versus low inflammation marker category and GBC passed multiple comparisons testing. It is also possible that some cytokines may not be stable when stored for long periods of time [35], which is particularly relevant for the Shanghai samples, which were collected 15–20 years ago. However, since degradation of cytokine levels over time would not be expected to differ by case-control status, cytokine degradation would only be expected to attenuate results.

This study also has a number of strengths. Using multiplexed assays, we conducted the most comprehensive analysis of local and systemic inflammatory markers and GBC to date. We identified many associations consistently in both bile and serum using a gallstone comparison group. The measurement of inflammation markers in bile is particularly unique, as bile is a challenging biospecimen to obtain and handle. In addition, we verified our results in an independent study from Chile, which has among the highest rates of GBC in the world.

5. Conclusions

We found strong associations between local and systemic immune markers and GBC. CCL20, CRP, CXCL10, CXCL8, resistin, and SAA seem to be particularly attractive markers for additional evaluation in etiologic and perhaps translational studies; if confirmed as robust biomarkers, these markers may also have clinical utility by helping to identify gallstone patients at the greatest risk for developing GBC. Future studies with a larger number of cases and normal controls as well as gallstone patients would provide further insight into the role of these markers across the natural history of GBC.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Inflammation markers are elevated in gallbladder cancer versus gallstone patients

Changes in local inflammation markers are generally reflected systemically in blood

CCL20, CRP, CXCL10, IL-8, resistin, and SAA had particularly robust associations

Acknowledgments

We thank the collaborating surgeons and pathologists in Shanghai and the Gallbladder Cancer Chile Working Group (GBCChWG) in Chile for assistance with field work, including patient recruitment and pathology review; Chia–Rong Cheng, Lu Sun, and Kai Wu of the Shanghai Cancer Institute and Johanna Acevedo and Paz Cook of the Pontificia Universidad Católica the for coordinating data and specimen collection; and Shelley Niwa of Westat and Michael Curry of IMS for support with study and data management. This work was supported by general funds from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), CONICYT/FONDAP/15130011, and Fondo Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo en Salud (FONIS) #SA11I2205. These funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. DCEG did participate in the review and approval of the manuscript; however, the study authors functioned as investigators without direction or interference by DCEG.

Abbreviations

- CVs

coefficients-of variation

- CI

confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- GBC

gallbladder cancer

- ICCs

intraclass correlation coefficients

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantification

- MSD

Meso Scale Discovery

- OR

odds ratio

- SAA

serum amyloid A

- ULOQ

upper limit of quantification

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion protein 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Castro FA, Koshiol J, Hsing AW, Devesa SS. Biliary tract cancer incidence in the United States-Demographic and temporal variations by anatomic site. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1664–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randi G, Malvezzi M, Levi F, Ferlay J, Negri E, Franceschi S, et al. Epidemiology of biliary tract cancers: an update. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:146–59. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertran E, Heise K, Andia ME, Ferreccio C. Gallbladder cancer: incidence and survival in a high-risk area of Chile. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2446–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Key C, Meisner ALW. Cancers of the Liver and Biliary Tract. In: Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner M-J, editors. SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: US SEER Program, 1988–2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. Bethesda: NIH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nogueira L, Freedman ND, Engels EA, Warren JL, Castro F, Koshiol J. Gallstones, cholecystectomy, and risk of digestive system cancers. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;179:731–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591–602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shebl F, Andreotti G, Meyer T, Gao Y, Rashid A, Yu K, et al. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in relation to biliary tract cancer and stone risks: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1424–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shebl FM, Andreotti G, Rashid A, Gao YT, Yu K, Shen MC, et al. Diabetes in relation to biliary tract cancer and stones: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:115–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsing AW, Sakoda LC, Rashid A, Chen J, Shen MC, Han TQ, et al. Body size and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:811–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreotti G, Liu E, Gao YT, Safaeian M, Rashid A, Shen MC, et al. Medical history and the risk of biliary tract cancers in Shanghai, China: implications for a role of inflammation. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:1289–96. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9802-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu E, Sakoda LC, Gao YT, Rashid A, Shen MC, Wang BS, et al. Aspirin use and risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1315–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Sharma KL, Mittal B. Candidate gene studies in gallbladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mutation research. 2011;728:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsing AW, Sakoda LC, Rashid A, Andreotti G, Chen J, Wang BS, et al. Variants in inflammation genes and the risk of biliary tract cancers and stones: a population-based study in China. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6442–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro FA, Koshiol J, Hsing AW, Gao YT, Rashid A, Chu LW, et al. Inflammatory gene variants and the risk of biliary tract cancers and stones: a population-based study in China. BMC cancer. 2012;12:468. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai CH, Lau WY. Gallbladder cancer--a comprehensive review. The surgeon : journal of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and Ireland. 2008;6:101–10. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(08)80073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Simopoulos C, Polychronidis A, Gatter KC, Harris AL, et al. Hypoxia inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha are associated with VEGF expression and angiogenesis in gallbladder carcinomas. Journal of surgical oncology. 2006;94:242–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakakubo Y, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, Hida Y, Oshikiri T, Suzuoki M, et al. Clinical significance of immune cell infiltration within gallbladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1736–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemp TJ, Castro FA, Gao YT, Hildesheim A, Nogueira L, Wang BS, et al. Application of multiplex arrays for cytokine and chemokine profiling of bile. Cytokine. 2015;73:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enjoji M, Nakamuta M, Yamaguchi K, Ohta S, Kotoh K, Fukushima M, et al. Clinical significance of serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor in biliary disease and carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1167–71. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i8.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seki S, Kitada T, Sakaguchi H, Hirohashi K, Kinoshita H. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence of human gallbladder. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2002;97:2146–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaturvedi AK, Kemp TJ, Pfeiffer RM, Biancotto A, Williams M, Munuo S, et al. Evaluation of multiplexed cytokine and inflammation marker measurements: a methodologic study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1902–11. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Wang BS, et al. Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1577–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seruga B, Zhang H, Bernstein LJ, Tannock IF. Cytokines and their relationship to the symptoms and outcome of cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2008;8:887–99. doi: 10.1038/nrc2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purdue MP, Hofmann JN, Kemp TJ, Chaturvedi AK, Lan Q, Park JH, et al. A prospective study of 67 serum immune and inflammation markers and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122:951–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-481077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trabert B, Pinto L, Hartge P, Kemp T, Black A, Sherman ME, et al. Pre-diagnostic serum levels of inflammation markers and risk of ovarian cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) Screening Trial. Gynecologic oncology. 2014;135:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badolato R, Wang JM, Murphy WJ, Lloyd AR, Michiel DF, Bausserman LL, et al. Serum amyloid A is a chemoattractant: induction of migration, adhesion, and tissue infiltration of monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:203–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:659–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Kampen O, Buch S, Nothnagel M, Azocar L, Molina H, Brosch M, et al. Genetic and functional identification of the likely causative variant for cholesterol gallstone disease at the ABCG5/8 lithogenic locus. Hepatology. 2013;57:2407–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.26009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian GS, Ross RK, Yu MC, Yuan JM, Gao YT, Henderson BE, et al. A follow-up study of urinary markers of aflatoxin exposure and liver cancer risk in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological methods. 2013;18:137–50. doi: 10.1037/a0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanderWeele TJ. Bias formulas for sensitivity analysis for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 2010;21:540–51. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181df191c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harland EC, Cardeilhac PT. Excretion of carbon-14-labeled aflatoxin B1 via bile, urine, and intestinal contents of the chicken. American journal of veterinary research. 1975;36:909–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehling J, Tacke F. Role of chemokine pathways in hepatobiliary cancer. Cancer letters. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C, et al. American Heart A. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.