Abstract

Context

Over the past decade, the introduction of generic versions of newer antidepressants and the release of FDA-warnings regarding suicidality in children, adolescents, and young adults may have had an impact on cost and quality of depression treatment.

Objectives

To examine longitudinal trends in service use, spending, and treatment quality for depression.

Design

Observational, trend study.

Setting

Florida, Medicaid enrollees from July 1996 to June 2006.

Subjects

Annual cohorts aged 18-64 diagnosed with depression.

Main Outcome Measures

Mental-health spending adjusted for inflation and case mix and components of mental-health spending, including inpatient, outpatient, and medication expenditures. Quality measures included measures of medication adherence, psychotherapy, and follow-up visits.

Results

Mental-health spending increased from an average of $2802 per enrollee to $3610 over this time period (29% increase). This increase occurred despite a mean decrease in inpatient spending (from $641 per enrollee to $373) and was driven primarily by an increase in pharmaceutical spending (up 110%) the bulk of which was due to spending on antipsychotics (up 949%). The percentage of enrollees with depression who were hospitalized decreased from 57% to 37% and the percentage using psychotherapy decreased from 9% to 5%. Antidepressant use increased from 82% to 87%, anxiety medication use was unchanged at 64%, and antipsychotic use increased from 27% to 42%. Changes in treatment quality were mixed, with measures of antidepressant use improving slightly, measures examining follow-up visits decreasing, and measures of psychotherapy utilization fluctuating.

Conclusions

Over a ten-year period, we found a substantial increase in spending for enrollees with depression associated with minimal improvements in quality of care. Antipsychotic use contributed significantly to the increase in spending while contributing little to traditional measures of quality.

Keywords: Depression, spending, quality, antidepressants, antipsychotics

Depression affects nearly 1 in 5 adults in the United States over their lifetime1 and has significant personal and societal costs.2 Untreated depression is associated with significant clinical morbidity and worsens the morbidity of other chronic diseases.3 Depression results in increased health care use and costs,4, 5 incurs significant emotional suffering and lost work productivity,6-8 and is linked to premature death.9

During the 1980's and 1990's, the number of adults diagnosed and treated for depression increased and the modality of treatment shifted. The percentage of adults with depression who received antidepressants increased and the percentage who received psychotherapy or were hospitalized for depression decreased.10 As a consequence of the shift away from psychotherapy and hospitalization, estimates of the average cost per treated patient decreased.11 The introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI's) as well as other new antidepressants (such as bupropion, venlafaxine, etc.) contributed to these treatment trends. The newer medications have a lower incidence of potentially fatal side effects at high therapeutic levels and interactions with commonly consumed foods than previously available antidepressants and allowed primary care physicians to play a larger role in assessing and treating depression.12 Despite the more common use of antidepressant medications for depression, several studies examining quality of depression treatment showed generally low performance throughout the 1990s.13-15

In the past decade, multiple developments may have had an impact on spending and antidepressant utilization for the treatment of depression. Beginning in 1999, the SSRI's as well as other new antidepressants such a bupropion began to come off-patent, potentially lowering cost of care and further increasing usage as generics became available.16 The FDA approved new antidepressants for the treatment of depression, including escitalopram in 2002 and duloxetine in 2004, as well as multiple new formulations of previously approved medications (e.g. Wellbutrin XL®). After gaining approval in 1997, direct to consumer advertising of antidepressants may have increased the acceptance and use of antidepressants.17 In 2004, the FDA-issued warnings about the increased risk of suicidal thoughts among children and young adults receiving treatment with SSRI's, likely decreasing use of antidepressants in children with some possible spill-over to use in adult populations.18

In this study, we examined changes in depression treatment, spending, and quality between July 1996 and June 2006 in a Medicaid program from a large and diverse state (Florida). We addressed the following questions: 1) how have treatment trends changed over time; 2) how have the different components of mental health spending – inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceutical- changed; and 3) has there been any improvement in the quality of depression care?

Methods

Data and Study Sample

We used administrative data (eligibility and claims files) from Florida's Medicaid program for fiscal years 1996-2005 (Florida's Medicaid fiscal year runs from July 1st to June 30th). We restricted our analyses to these years because Florida moved large numbers of Medicaid enrollees into prepaid mental health plans that may not reliably report encounter data beginning in fiscal year 2006. Through fiscal year 2005, Florida's Medicaid program was primarily fee-for-service, had enrollment ranging from 2.1 to 2.9 million people, and was the fourth largest in the United States.19 Florida's Medicaid data include information on enrollees’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, eligibility category, clinical diagnoses, utilization (including pharmaceuticals), and spending.

We identified annual cohorts of adults with depression consisting of enrollees between the ages of 18-64 with either one or more hospitalizations with a principal diagnosis of depression, or at least two outpatient claims of depression (ICD9: 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, and 311) on different days.15, 20-23 A limitation of claims data are that there could be false-positives and false-negatives in establishing the cohort. Prior research has shown that using a less stringent algorithm of identifying depression in administrative data is associated with a high specificity (i.e. low false-positive rates) but at the expense of sensitivity (i.e. higher false-negative rates).24 The implications of this algorithm are that our cohort is likely to have few false positives but that there are many enrollees who may have depression but were not included in our cohort. For these individuals we cannot say anything about their service utilization or treatment quality. Enrollees were excluded if they were enrolled for fewer than 10 months out of the fiscal year or enrolled through family planning services. In addition, enrollees were excluded if they were dually eligible for Medicare, or enrolled in a health maintenance organization or prepaid mental health plan at any time during the fiscal year because of the possibility of incomplete encounter data. We also excluded enrollees who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD9-CM: 295) or bipolar disorder (ICD9-CM: 296.0-296.1; 296.4-296.8; 301.13) during the fiscal year because we would expect their treatment patterns to be defined by their primary mental health diagnoses. A summary of these exclusions in available on the website as eAppendix 1.

Patient characteristics and outcome measures

Patient characteristics, outcome measures, and analyses were conducted separately within each fiscal year for each enrollee and are presented as two-year averages to minimize year-to-year fluctuation.

Patient Characteristics

We used eligibility files from Florida Medicaid to identify enrollee's age, sex, race or ethnicity, and Medicaid eligibility. For race and ethnicity, we combined Hispanic and other categories because, prior to 1999, enrollees who were eligible for Medicaid via Supplemental Security Income (SSI) only included racial categories of black, white and other.25, 26 We identified the following subtypes of depression: major depressive disorder with psychosis (ICD9-CM: 296.24 and 296.34), major depressive disorder without psychosis (ICD9-CM: 296.20-296.23, 296.25-296.26, 296.30-296.33, and 296.35-296.36), and other depression which includes both depression disorder not otherwise specified (ICD9-CM: 311) and dysthymia (ICD9-CM: 300.4). We assigned one of the four types to each enrollee with depression via the hierarchy above. In other words, if an enrollee had claims for both other depression and major depressive disorder without psychosis we identified that enrollee as having major depressive disorder without psychosis. We identified individuals as having co-morbid anxiety or adjustment disorder (ICD9-CM 300.0-300.3, 300.5-300.9, 308.0-309.9), co-morbid substance use disorder (SUD) (ICD9-CM: 291-292, 303-305), or other co-morbid mental health condition (ICD9-CM: 290-319 excluding the above diagnoses) if they had at least one ICD9-CM code indicating the condition within the fiscal year. In addition because of the high levels of physical co-morbidity in depression, we identified individuals as having the following co-morbid physical illness as defined by the presence of one or more relevant ICD9-CM codes: HIV/AIDS, COPD or asthma, diabetes, hypertension, and back and joint pain. These conditions were chosen because they were the most common chronic medical conditions in our cohort. We identified individuals as being treated by a psychiatrist if they had one or more claims submitted by a psychiatrist during the fiscal year.

Utilization and Spending Measures

We examined the proportion of enrollees with depression who received an inpatient hospitalization, psychotherapy visits, or pharmacologic treatment with antidepressants or other psychotropic medication classes. We examined medication utilization by depression type. Numerators were defined as the number of enrollees who received the service for the given year and denominators were defined as the total number of eligible enrollees with depression.

We tabulated total annual spending and mental health spending for each enrollee. We categorized mental health spending into inpatient, outpatient and pharmaceutical spending. For each category we summed the amount paid in claims. For enrollees who were enrolled for only 10 or 11 months of the fiscal year, we annualized the claims. Using the Southern Region medical care component of the consumer price index (CPI), we adjusted the dollar amounts to fiscal year 2005 dollars.

We classified a claim as mental health if it met any of the following criteria: 1) the procedure code was mental health specific; 2) the place of service was mental health specific; 3) a mental health diagnosis was present; or 4) the provider was a mental health specialist. Claims were then categorized into inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceutical claims. Inpatient stays included only admissions with a mental health diagnosis reported as the primary diagnosis. Any mental health claims that occurred during the period of hospitalization were included in the inpatient claims. We further categorized outpatient spending into psychotherapy, other physician or clinic visits, and other outpatient services (e.g. case management, treatment planning, psychosocial rehabilitation, day treatment programs, laboratory testing, and other outpatient wrap around services). Claims that included coding for both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (e.g. 90805, 90807, and 90809) were categorized as psychotherapy for the spending and utilization measures. Mental health pharmaceutical claims were examined in aggregate as well as by medication class. Medication classes examined included antidepressants, antipsychotics, antianxiety medications, and other mental health medications (specific classification is available on the Archives website as eAppendix 2).

Quality measures

Published guidelines recommend treatment during both acute-phase and continuation-phase episodes.27 In this study we focus on acute-phase measures. We identified individuals from our cohort as having a new, acute-phase episode of depression if an individual entered outpatient treatment with no previous claims for mental health diagnoses for the previous 120 days and no antidepressant claims between 31 and 120 days prior to the initial diagnosis (given that some patients may be started on medication before actually seeing the doctor), or if an individual was discharged from an inpatient hospitalization with a principal diagnosis of depression.

We defined acute-phase episodes as lasting 112 days (16 weeks). We used this period to accommodate response to treatment and inefficiencies that can occur in usual care. The index date of the acute phase episode was defined as the date of the first depression diagnosis or the first day after discharge from the hospital. Our quality measures are informed by prior research and published guidelines. For individuals who filled an antidepressant prescription within 30 days of the index date, we defined adequate drug treatment as receiving 75% or more days of antidepressants from the first antidepressant fill to the end of the acute-phase episode28, 29 and adequate follow-up as three or more follow-up visits during the acute-phase episode.30 For individuals who received psychotherapy within 30 days of the index date, we defined minimally adequate psychotherapy as 4 or more visits during the acute-phase episode based on previous studies.13, 21, 31, 32 Finally, for individuals being discharged from a psychiatric hospitalization for depression, we defined two measures to examine adequate follow-up visits based on measures in the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS): the receipt of an ambulatory mental health visit within 7 days or 30 days of hospital discharge. Numerators for these quality endpoints were the number of eligible acute phase episodes that met the definitions above and denominators were the number of eligible acute phase episodes. Individuals who were not continuously enrolled for the acute-care episode were excluded (5.5%) as well as individuals who were hospitalized during the acute-care episode (6.8%). Episodes that spanned fiscal years were included in the fiscal year of the index date.

Analyses

We first described the demographic characteristics of enrollees identified as having depression for the first two and last two years of the 10-year, period studied. We compared changes in demographic characteristics using chi-square for categorical data and t-tests for continuous data.

We then examined unadjusted trends in utilization, spending, and quality of care over ten years. We report trends over ten years in mean total spending, mental health spending, mental health component spending, and pharmaceutical spending by medication class. We calculated the percentage increase in spending after combining the first two and last two fiscal years to minimize the impact of year-to-year fluctuation. As a supplement to unadjusted spending data, we adjusted each spending category for changes in underlying demographics (age, sex, race, eligibility) and medical and psychiatric co-morbidities using a linear GEE equation clustered on individuals to estimate spending.33 We present the percent of the unadjusted changes that are attributed to demographic changes over time as well as the remaining contributions of each spending category adjusted for changing demographics. Finally we described trends in quality of care and test for trends utilizing the Cochran-Armitage trend test.

Results

The number of enrollees with depression identified annually varied from 8,970 to 13,265 with more enrollees identified towards the end of our study period. The rate of identified depression remained relatively constant and was 5.6% in fiscal years 1996 and 1997 and 5.7% in fiscal years 2004 and 2005. Many enrollees were identified in more than one annual cohort. The total number of unique individuals identified with depression in our study period was 56,805. There were 107,931 observations over the 10 years. Demographically, the racial make-up of our sample changed to include a larger proportion of patients with identified depression who are Hispanic or other (Table 1). This change in demographics likely reflects both the change in Social Security Administration's definition of race as well as an increase in the Hispanic population in Florida.34, 35 The percentage of our sample that had major depressive disorder with psychosis increased over this time period. In addition the percentage that had other forms of depression increased but remained a small portion. The percentage of our sample that had co--morbid anxiety and adjustment disorder diagnoses decreased and those with substance use disorders increased. With the exception of HIV/AIDS, all other physical co-morbidities increased during this time. The percent of enrollees with depression treated by psychiatrists decreased over this time period.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics for enrollee's treated for depression: FY's 1996 and 1997 and FY's 2004 and 2005

| Demographics | FY's 1996, 1997 N=18,663 | FY's 2004, 2005 N=24,312 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Age | 43.5 (12.4) | 44.5 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 23% | 24% | 0.013 |

| Female | 77% | 76% | |

| Race | |||

| White | 51% | 44% | <0.001 |

| Black | 13% | 14% | |

| Hispanic/Other | 36% | 42% | |

| Eligibility | |||

| SSI | 70% | 67% | <0.001 |

| AFDC/TANF | 24% | 22% | |

| Other | 6% | 11% | |

| Depression Subtype | |||

| MDD* with psychosis | 15% | 21% | <0.001 |

| MDD* without psychosis | 84% | 74% | <0.001 |

| Other Depression** | <1% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Comorbid MH | |||

| Anxiety DO | 37% | 31% | <0.001 |

| Substance Use | 11% | 18% | <0.001 |

| Other | 10% | 10% | 0.184 |

| Comorbid Health | |||

| HIV/AIDS | 5% | 5% | 0.160 |

| Diabetes | 12% | 20% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 24% | 37% | <0.001 |

| Back/Joint pain | 44% | 52% | <0.001 |

| COPD/asthma | 25% | 30% | <0.001 |

| Psychiatrist | 83% | 72% | <0.001 |

Observations refer to data on a person-year basis. In fiscal year 1996 there were 9662 observations and in fiscal year 1997 there were 9001 observations. Forty-two percent of patients in fiscal year 1996 were also in fiscal year 1997. In fiscal year 2004 there were 13,265 observations and in fiscal year 2005, 11,047. 39% of patients in fiscal year 2004 were also in fiscal year 2005.

MDD stands for Major Depressive Disorder

Other depression includes depression NOS (ICD9-CM: 311) and dysthymia (ICD9-CM: 300.4)

Utilization

Over the period studied, the percentage of depressed enrollees who received psychotherapy declined from 57% to 37% and the percentage hospitalized fell from 9% to 5% (data not shown). In contrast, the percentage of depressed enrollees who filled prescriptions within any medication classes remained the same (anxiety medications) or increased (antidepressants, antipsychotics and other mental health medications) over this time period (Table 2). Trends were similar for all subtypes of depression. Of particular note are the increases in antipsychotic use for all subtypes of depression, not just major depressive disorder with psychosis.

Table 2.

Proportion of Florida Medicaid enrollees treated by medication class by depression type. Fiscal years 96&97 versus fiscal years 04&05.

| FY 96 & 97 | FY04 & 05 | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

| Antidepressants | |||||

| All enrollees with depression | 81 | 80-81 | 87 | 86-87 | <0.001 |

| MDD with psychosis | 86 | 85-88 | 92 | 91-93 | <0.001 |

| MDD without psychosis | 81 | 80-81 | 86 | 86-87 | <0.001 |

| Other depression | 47 | 36-59 | 75 | 73-78 | <0.001 |

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| All enrollees with depression | 26 | 25-26 | 42 | 41-43 | <0.001 |

| MDD with psychosis | 62 | 60-64 | 79 | 78-80 | <0.001 |

| MDD without psychosis | 20 | 19-20 | 33 | 32-34 | <0.001 |

| Other depression | 9 | 2-15 | 20 | 17-22 | 0.021 |

| Antianxiety medications | |||||

| All enrollees with depression | 63 | 62-63 | 64 | 64-65 | <0.001 |

| MDD with psychosis | 69 | 68-71 | 77 | 76-78 | <0.001 |

| MDD without psychosis | 62 | 62-63 | 62 | 62-63 | 0.727 |

| Other depression | 21 | 11-30 | 42 | 39-45 | <0.001 |

| Other mental health medications | |||||

| All enrollees with depression | 16 | 15-16 | 27 | 26-27 | <0.001 |

| MDD with psychosis | 16 | 14-17 | 22 | 21-23 | <0.001 |

| MDD without psychosis | 16 | 15-16 | 29 | 28-29 | <0.001 |

| Other depression | 8 | 2-14 | 18 | 15-20 | 0.023 |

Spending

After adjusting for inflation as well as demographic and medical and psychiatric co-morbidities, spending for mental health treatment increased 29% from $2,802 to $3,610 (Table 3). Spending for inpatient mental health dropped more than 40% while spending for outpatient service visits increased by 21%. Spending for other outpatient services and physician and clinic visits increased more than that for psychotherapy.

Table 3.

Adjusted trends in average mental health spending per enrollee with identified depression: Fiscal year 1996-fiscal year 2005.

| FY 1996, 1997 | FY 2000, 2001 | FY 2004, 2005 | Change from FY's 1996, 1997 to FY's 2004, 2005 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | Unadjusted | |||||

| Average Spending (95% CI) | Average Spending (95% CI) | Average Spending (95% CI) | $ Increase | Difference ($) | Difference ($) | |

| Mental Health Care | 2802 (2791-2813) | 3763 (3282-3303) | 3610 (3599-3621) | 29% | 808 | 1134 |

| Inpatient | 641 (637-645) | 567 (563-572) | 373 (369-378) | −42% | −268 | −179 |

| Outpatient | 1267 (1261-1274) | 1594 (1587-1600) | 1509 (1502-1515) | 21% | 242 | 474 |

| Therapy | 146 (145-146) | 123 (123-124) | 150 (150-150) | 3% | 4 | 7 |

| Physician/Clinic visits | 174 (174-174) | 225 (225-226) | 214 (213-214) | 23% | 40 | 42 |

| Other Services | 945 (939-952) | 1237 (1231-1244) | 1133 (1127-1140) | 20% | 188 | 425 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 840 (838-843) | 1580 (1577-1583) | 1768 (1765-1771) | 110% | 928 | 880 |

| Antidepressants | 457 (456-458) | 675 (674-676) | 557 (556-558) | 22% | 100 | 70 |

| Antipsychotics | 82 (80-84) | 494 (493-496) | 860 (859-862) | 949% | 778 | 716 |

| Anxiety Medications | 161 (161-161) | 226 (225-226) | 89 (88-89) | −45% | −72 | −88 |

| Other medication classes | 61 (61-62) | 187 (186-187) | 261 (261-262) | 328% | 200 | 192 |

Estimates adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, eligibility, mental health co-morbidities, and physical health co-morbidities via GEE linear equation clustered on individual with exchangeable correlation.

Annualized estimates and dollar amounts are CPI-adjusted to fiscal year 2005

Unadjusted estimates can be seen in Supplement 1.

Spending on mental health pharmaceuticals increased by 110% over the ten years studied. Spending for antidepressants increased 22% over the 10-year period and peaked in fiscal years 2000 and 2001. Spending on anti-anxiety agents decreased substantially during the study period, despite no change in their utilization. By contrast, spending on antipsychotics (up 949%) and other medication classes (up 328%) increased dramatically. By the end of the ten-year period, average spending on antipsychotics ($860) surpassed average spending on antidepressants ($557). Among antipsychotics, spending on quetiapine was greatest, followed by risperidone.

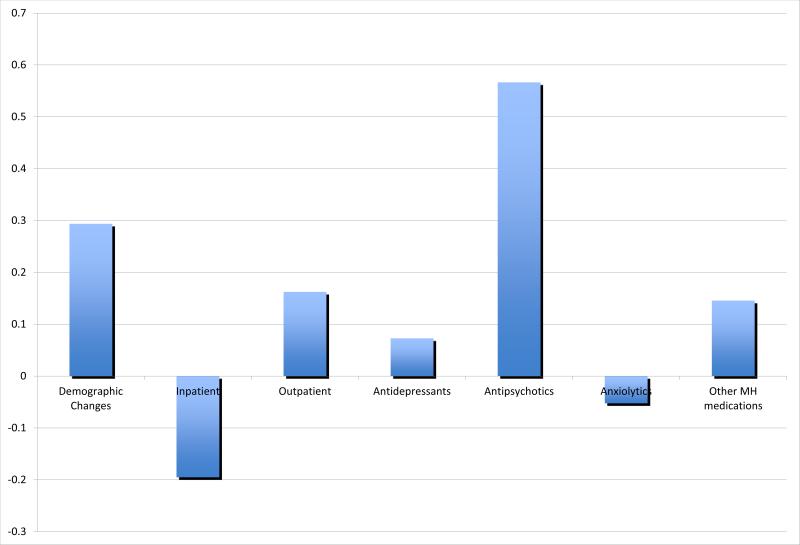

Compared to unadjusted data, adjusting for patient's demographic and clinical characteristics decreased the change in absolute spending from $1,135 to $808 (Table 3 and eAppendix 3). Spending on inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceuticals show similar patterns between adjusted and unadjusted estimates. The increased use of antipsychotics appeared to have the largest impact on increased spending for mental health care, and the decrease in inpatient spending appeared to have the largest impact in reducing overall mental health spending (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Contributions of demographic changes and mental health care components to increases in mental health care spending in Florida Medicaid from fiscal years 1996 and 1997 to fiscal years 2004 and 2005.

Legend under Figure 1: Data adjusted for demographic factors, mental health co-morbidities, and physical co-morbidities.

Quality

We identified 2,523 outpatient, acute phases in fiscal years 1996 and 1997; 2,836 in fiscal years 2000 and 2001; and 3,017 in fiscal years 2004 and 2005 (Table 4). The percentage of acute-phase episodes that were treated with antidepressants increased from 65% to 75% over this ten-year period. In contrast, the percentage of episodes treated with psychotherapy decreased from 43% to 27%.

Table 4.

Trends in depression quality measures: Fiscal years 1996-2005

| FY 1996 and 1997 | FY 2000 and 2001 | FY 2004 and 2005 | Trend* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p-value | |

| Outpatient | 2523 | n/a | 2836 | n/a | 3017 | n/a | |

| Received Pharmacotherapy | 1643 | 65% | 2069 | 73% | 2268 | 75% | <0.01 |

| Received Psychotherapy | 1075 | 43% | 930 | 33% | 812 | 27% | <0.01 |

| Outpatient Acute-Phase Quality Measures | |||||||

| Pharmacotherapy** | |||||||

| Minimally adequate treatment | 965 | 59% | 1333 | 64% | 1546 | 68% | <0.01 |

| Minimally adequate follow-up | 319 | 19% | 304 | 15% | 247 | 11% | <0.01 |

| Minimally adequate psychotherapy*** | 154 | 14% | 88 | 9% | 108 | 13% | 0.35 |

| Post-Hospitalization | 1028 | n/a | 1350 | n/a | 1317 | n/a | |

| Received Pharmacotherapy | 778 | 76% | 1021 | 78% | 934 | 75% | 0.47 |

| Received Psychotherapy | 332 | 32% | 291 | 22% | 233 | 17% | <0.01 |

| Post-Hospitalization Acute-Phase Quality Measures | |||||||

| Pharmacotherapy** | |||||||

| Minimally adequate treatment | 323 | 42% | 528 | 52% | 455 | 49% | <0.01 |

| Minimally adequate follow-up | 275 | 35% | 316 | 31% | 281 | 30% | 0.02 |

| Minimally adequate psychotherapy*** | 90 | 27% | 66 | 23% | 86 | 37% | 0.02 |

| Post-hospital follow-up visit within 7 days† | 152 | 15% | 188 | 14% | 203 | 16% | 0.32 |

| Post-hospital follow-up visit within 30 days | 354 | 34% | 416 | 32% | 413 | 33% | 0.51 |

Cochran-Armitage two-sided trend test

Denominator for these measures is the number of acute-phase episodes that received pharmacotherapy.

Denominator for these measures is the number of acute-phase episodes that received psychotherapy

Denominator for this measure is the number of post-hospitalization acute-phase measures. 1028 for FY's 1996 and 1997; 1310 for FY's 2000 and 2001; 1252 for FY"s 2004 and 2005.

During the acute phase period, individuals who received antidepressants had minimally adequate treatment if they filled an antidepressant prescription for 75% of the days and had minimally adequate follow-up if they had 3 or more health provider visits. Individuals who received psychotherapy had minimally adequate psychotherapy if they had 4 or more visits. Individuals who were post-hospitalization had minimally adequate follow-up if they had a visit with a mental health provider within 14 days after hospital discharge.

Of the patients that received antidepressants, the proportion that received minimally adequate drug treatment increased slightly over time from 59% to 68% (p-value = <0.01) and the proportion that received minimally adequate follow-up visits decreased from 19% to 11% (p-value=<0.01). Of those outpatients who received psychotherapy, the proportion that received at least 4 sessions within the acute phase fluctuated from 9% to 14% (p-value=N.S).

We identified 1,028 post-hospitalization acute phases in fiscal years 1996 and 1997; 1,350 in fiscal years 2000 and 2001; and 1,317 in fiscal years 2004 and 2005 (Table 4). The proportion of acute phases that included antidepressants within 30 days of discharge did not change significantly during the ten years studied. The proportion that included psychotherapy decreased from 32% to 17% (p-value = <0.01).

Of the post-hospital phases that included antidepressants, the proportion with adequate drug treatment increased from 42% to 49% (p-value = <0.01) and the proportion that included adequate follow-up visits decreased slightly from 35% to 30% (p-value = 0.02). The proportion of post-hospitalization acute phases that included 4 or more sessions of psychotherapy during the acute phase fluctuated from 23% to 37% during the time period studied (p-value = 0.02). Finally, the proportion of post-hospital acute phases that included a follow up visit within 7 or 30 days remained low with no significant trend. An examination of continuation-phase measures showed similar trends: i.e. an increase in antidepressant use with no significant change in appropriate follow-up visits (data available online in eAppendix 4).

Discussion

We examined treatment of patients with depression including spending and quality of care in Florida Medicaid between 1996 and 2005 and had four notable findings. First, there was a 29% increase in mental health spending per enrollee with depression after adjusting for inflation and changes in patient's demographic and clinical characteristic. Second, this increase occurred despite decreases in inpatient costs per enrollee. Third, spending on pharmaceuticals increased by more than 110%, with the bulk of that increase due to antipsychotics rather than antidepressants. Finally, despite the increased expenditures there were mixed changes in the quality-of-care measures that we studied: measures involving antidepressants improved slightly over the 10-year period; those involving therapy fluctuated; and those involving follow-up appointments deteriorated.

Because of prior trends showing decreasing use of inpatient services and psychotherapy, and the introduction of generic, newer generation antidepressants, we expected to find decreasing expenditures per depressed enrollee. Nevertheless, we found just the opposite, with increasing use of antipsychotics the largest contributor to rising costs. Because our sample does not include individuals with co-morbid schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, this increase in antipsychotics is particularly notable.

During the period of this study, the use of adjunctive antipsychotics was recommended for the small portion of depressed patients who also experience psychotic symptoms36 and as one of several augmentation strategies for individuals with limited or poor response to antidepressants alone.37 Antipsychotics may have also been used off-label to treat anxiety38 or insomnia39--particularly in those for whom alternative treatments may not be appropriate (e.g., benzodiazepines in patients with substance use disorders). Our data show an increase in antipsychotic use within all subtypes of depression. Further, one would expect the more recent FDA-approvals of both aripiprazole (2007) and quetiapine extended-release tablets (2009) as adjunctive treatment to antidepressants for major depressive disorder to accelerate this trend.

In our adjusted analyses, we controlled for co-morbid substance use disorders and anxiety disorder and thus it seems unlikely that changes in clinical case mix accounts for the widespread (and growing) use of antipsychotics in patients who are being treated for depression. Our results are consistent with other research that has found that the introduction of atypical antipsychotics has expanded the indications for which antipsychotics are prescribed.40 Given the risk of metabolic side effects associated with several of the atypical antipsychotics,41—including the most commonly used antipsychotics in this study—the large impact this use has on potential morbidity as well as costs of care underscores the need for the development of targeted guidelines to address antipsychotic use for individuals with depression as well as cost-effectiveness studies examining antipsychotic use in treatment-resistant depression.

The juxtaposition of increased mental health spending per enrollee without a substantial improvement in depression treatment quality is striking. While public reporting of quality measures has led to greater improved performance for many aspects of care, quality performance for depression has improved more slowly and remains less than optimal. In general, individuals with Medicaid receive lower quality care42 and individuals with severe mental illness receive lower quality medical care.43 Factors affecting the quality of care for depression can be classified into informational and attitudinal factors, financial barriers, and lack of profitability.44 Our data suggest gains in acceptance by providers and patients of both antidepressant and antipsychotic treatment, potentially reflecting the effective marketing of both types of medications by pharmaceutical companies. Despite these gains, the receipt of quality measures for depression remained low. This study does not explore the reasons for this ceiling. Past studies have suggested that individuals may view treatment of mental illness as less important than physical illnesses, and fear psychotropic medications as both being addictive and possibly interfering with natural emotions.45, 46 Collaborative care models have been identified as one of the most effective approach to improving quality of depression care and outcomes;47 however, the diffusion of this model has remained limited partially as a result of the limited funding for costs related to these models.48 Finally, the minimal rise in antidepressant spending could correspond to longer periods of treatment with antidepressants as has been shown in other research;49 however, this change would not be reflected in either the quality measures examining acute episodes of depression or simple rates of utilization.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to focus simultaneously on changes over time on utilization, spending, and quality for patients with depression. Although prior studies have examined spending up to 2007, they have not examined changes in cost per person past the year 2000 or by individual drug classes.11, 50 Our results are consistent with prior studies of overall mental health spending showing increasing expenditures for pharmacologic therapy and lower expenditures on inpatient care.11, 51, 52 Past studies focusing on use of antidepressants and other psychoactive medications through 2005 have documented increasing use of antidepressants, increasing use of antipsychotics for patients taking antidepressants, and decreased use of psychotherapy for patients taking antidepressants.53, 54 Unlike our study, these studies did not look specifically at a population of depressed patients. Our longitudinal findings of little change in quality of depression care are consistent with prior studies in the VA system55 and limited changes in national HEDIS measures over time.56, 57 Our findings of increased use of medications coupled with either similar or decreased use of mental health visits or psychotherapy is also consistent with literature documenting utilization trends for depression50 as well as for other psychiatric illnesses.58-60

There are several limitations to this study. Our claims data include information on diagnoses and services for patients who have been identified and treated for depression. They do not reflect population prevalence of depression because many individuals in the population may go undiagnosed and thus not be reflected in claims data. Our quality measures were based on process measures derived from guidelines and prior research; however, we were unable to assess patient outcomes. As a result, we are unable to answer whether or not the increased use of antipsychotics in patients with depression was associated with improved outcomes. Also, our costs reflect total mental health and substance abuse costs for the year and we did not attempt to separate out costs attributable to psychiatric co-morbidities. We felt that the strength of utilizing an observational sample was the ability to capture total spending associated with depression care that may include spending on co-morbid diagnoses. For example, if an individual was being treated for anxiety or substance use and then received a diagnosis of depression a month later, it would be difficult to parse out what elements of the previous spending were related to anxiety, substance use, or depression. Further, we controlled for changes in prevalence of co-morbidities in the model. There is a possibility that, over the ten years studied, that either coding completeness or upcoding of data occurred at different rates. To our knowledge, there were no changes in Florida Medicaid policy that would have incentivized upcoding and by examining only fee-for-service enrollees as well as categories of spending, we hoped to mitigate this issue to the extent possible.

Our analysis stops in June 2006 (the end of fiscal year 2005) and thus may not accurately reflect current practice. Since this time, more drugs similar to previous drug classes have been approved (desvenlafaxine and buproprion) as well as one new medication class (vilazodone). Further, the availability of generics continues to increase. Concurrent release of new antidepressant formulations with the release of more generic versions of existing antidepressants also occurred during our study time period. In addition since the time period of this study, the FDA has approved two atypical antipsychotics for adjunctive treatment in treatment-resistant depression. We would anticipate that this development could accelerate the trends in antipsychotic use and spending we observed in this study.

Finally, we have data only from a single state and the Medicaid enrollees in our study may not be representative of those in other Medicaid programs or of privately insured patients given their high levels of disability, co-morbidity, and low socioeconomic status. Studies have shown that Medicaid patients have higher rates of depression61 as well as higher rates of antipsychotic use as compared to commercially insured populations.62 At the same time, Medicaid enrollees often receive lower quality of care over a range of quality measures.42 Therefore, these results may overstate national trends in spending and medication use while understating trends in quality metrics. Nonetheless, examining spending and quality within the fourth largest Medicaid population is important as public insurance continues to cover a greater percentage of mental health and substance abuse costs over time and is anticipated to further expand under the Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act of 2009.52, 63, 64

In summary, over the ten-year period between 1996 and 2005 we found a substantial increase in spending for patients with depression associated with minimal improvements in quality of care. Much of the increased spending was due to pharmacotherapy, especially the use of antipsychotics. Our findings underscore the importance of continued efforts to improve quality of care for individuals with depression and the need to understand the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of using antipsychotics for the treatment of individuals with depression in the general community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Financial Disclosures

This work was supported by Grants R01-MH081819 and K01 MH071714 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors would like to thank Christina Fu for her programming expertise as well as Laura Cowieson and Kristen Bolt for their research assistance.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The Global Burden of Disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam A, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262(7):914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Sledge WH. Health and disability costs of depressive illness in a major U.S. corporation. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1274–1278. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(10):850–856. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950220060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2524–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berndt ER, Koran LM, Finkelstein SN, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, Miller IM, Thase ME, Trapp GA, Keller MB. Lost human capital from early-onset chronic depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):940–947. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers wtih depression. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3135–3144. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GP, Florio L, Hoff PA. Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Cathment Area Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:716–721. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss BG, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002;287(2):203–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Lowe SW, Berglund PA, Corey-Lisle PK. The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1187–1198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne C, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, Owen RR, Kader B, Spiro A, III, Hankin C, Herz LR, Pugh MJV, Kazis L, Miller DR, Berlowitz DR. Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Med Care. 2003;41(5):669–680. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062920.51692.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Kelton CM, Jing Y, Guo JJ, Patel NC. Utilization, price, and spending trends for antidepressants in the US Medicaid program. Research Social Aminstration Pharmacy. 2008 Sep;4(3):244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donahue JM, Berndt ER, Rosenthal M, Epstein AM, Frank RG. Effects of pharmaceutical promotion on adherence to the treatment guidelines for depression. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1176–1185. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libby AM, Orton HD, Vluck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):633–639. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of Research Development and Information, Mathematica Policy Research [September 28, 2007];The Medicaid Analytic Extract Chartbook. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/Downloads/MAX_Chartbook_2007.pdf.

- 20.Kniesner TJ, Powers RH, Coghan TW. Provider type and depression treatment adequancy. Health Policy. 2005;72:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katon WJ, Richardson L, Russo J, Lozano P, McCauley E. Quality of mental health care for youth with asthma and comorbid anxiety and depression. Med Care. 2006;44:1064–1072. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000237421.17555.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sewitch MJ, Blais R, Rahme E, Bexton B, Galarneau S. Receiving guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy for major depression: Impact on ambulatory and inpatient health service use. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:191–200. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Normand S-LT, Young AS, Goldman HH, Frank RG. The impact of parity on major depression treatment quality in the federal employees' health benefits program after parity implementation. Med Care. 2006;44(6):506–512. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215890.30756.b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spettell CM, Wall TC, Allison J, Calhoun J, Kobylinski R, Fargason R, Kiefe C. Identifying physician-recognized depression from administrative data: Consequences for quality management. Health Serv Res. 2003 Aug;38(4):1081–1102. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arday SL, Arday DR, Monroe S, Zhang J. HCFA's racial and ethnic data: Current accuracy and recent improvements. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(4):107–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott CG. Identifying the race or ethnicity of SSI recipients. Soc Secur Bull. 1999;62(4):9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fochtmann IJ, Gelenberg AJ. Guideline watch: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 2nd ed. American Pyshicatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Owen RR, Spiro A, III, Ash AS, Miller DR, Kazis L, Kader B, Cunningham F, Berlowitz DR. Monitoring depression care: In search of an accurate quality measure. Med Care. 2004;42:522–531. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000127999.89246.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rost K, Dickenson LM, Fortney JC, Westfall J, Hermann RC. Clinical improvement associated with conformance to HEDIS-based depression care. Mental Health Services Research. 2005 Jun;7(2):103–112. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-3781-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells KB, Sturm R. Care for depression in a changing environment. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995;14(3):78–89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, McCaffrey D, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Wells KB. The effects of primary care depression treatment on patients' clinical status and employment. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1145–1158. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon WJ, Simon GE, Russo J, Von Korff M, Lin EHB, Ludman E, Clechanowski P, Bush T. Quality of depression care in a population-based sample of patients with diabetes and major depression. Med Care. 2004 Dec;42(12):1222–1229. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Census Bureau [October 5, 2010];Current Population Survey Table Creator. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/cpstc/cps_table_creator.html. 2010.

- 35.U.S. Census Bureau [October, 5, 2010];Population Estimates for States by Race and Hispanic Origin. Jul;1:1996. http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/strh/srh96.txt. [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4 Suppl):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Arana GW. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. Sixth ed Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the department of Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(9):1175–1181. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philip NS, Mello K, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR, Price LH. Patterns of quetiapine use in psychiatric inpatients: an examination of off-label use. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Jan-Mar;20(1):15–20. doi: 10.1080/10401230701866870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications int he United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2011;20:177–184. doi: 10.1002/pds.2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newcomer JW. Metabolic considerations in the use of antipsychotic medications: a review of recent evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 1):20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landon BE, Schneider EC, Normand S-LT, Scholle SH, Pawlson LG, Epstein AM. Quality of care in Medicaid managed care and commercial health plans. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1674–1681. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:565–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drake R, Skinner J, Goldman HH. What explains the diffusion of treatments for mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1385–1392. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadam UT, Croft P, McLeod J, Hutchinson M. A qualitative study of patients' views on anxiety and depression. Br J Gen Pract. 2001 May;51:375–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zivin K, Kales HC. Adherence to depression treatment in older adults: A narrative review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(7):559–571. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: A comulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(11):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katon WJ, Zatzick D, Bond G, Williams J. Dissemination of evidence-based mental health interventions: Importance to the trauma field. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(5):611–623. doi: 10.1002/jts.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore M, Yuen HM, Dunn N, Mullee MA, Maskell J, Kendrick T. Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: a decriptive study using the general practice research database. BMJ. 2009;339:b3999. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frank RG, Goldman HH, McGuire TG. Trends in mental health cost growth: An expanded role for management? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):649–659. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mark TL, Levit KR, Buck JA, Coffey RM, Vandivort-Warren R. Mental health treatment expenditure trends, 1986-2003. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(8):1041–1048. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC. Trends in antidepressant utilization from 2001 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(5):611–616. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):848–856. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. Date. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cully JA, Zimmer M, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Quality of depression care and its impact on health service use and mortality among veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008 Dec;59(12):1399–1405. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Committee for Quality Assurance . The state of health care quality. Washington, DC: 2009. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Committee for Quality Assurance . The State of Health Care Quality. Washington, DC: 2003. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Busch AB, Ling DC, Frank RG, Greenfield SF. Changes in Bipolar-I Disorder Quality of Care During the 1990's. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):27–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.1.27-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Busch AB, Lehman AF, Goldman HH, Frank RG. Changes over time and disparities in schizophrenia treatment quality. Med Care. 2009;44(6):199–207. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818475b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996-2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:195–205. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibson TB, Lee TA, Vogeli CS, Hidalgo J, Carls GS, Sredl K, DesHarnais S, Marder wD, Weiss KB, Williams TV, Shields AE. A four-system comparison of patients with chronic illness: The Military Health System, Veterans Health Administration, Medicaid, and Commercial Plans. Mil Med. 2009;174:936–943. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-03-7808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Domino ME, Swartz MS. Who are the enw users of antipsychotic medications? Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):507–514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.5.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mark TL, Levit KR, Vandivort-Warren R, Buck JA, Coffey RM. Changes in US spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1996-2005, and implications for policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):284–292. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Foster RS. Estimated financial effects of the “Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act” as Amended. Department of Health & Human Services; Baltimore: Apr 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.