Abstract

Background

Evidence that different neuropsychiatric conditions share genetic liability has increased interest in phenotypes with ‘cross-disorder’ relevance, as they may contribute to revised models of psychopathology. Cognition is a promising construct for study; yet, evidence that the same cognitive functions are impaired across different forms of psychopathology comes primarily from separate studies of individual categorical diagnoses versus controls. Given growing support for dimensional models that cut across traditional diagnostic boundaries, we aimed to determine, within a single cohort, whether performance on measures of executive functions (EFs) predicted dimensions of different psychopathological conditions known to share genetic liability.

Methods

Data are from 393 participants, ages 8 to 17, consecutively enrolled in the Longitudinal Study of Genetic Influences on Cognition (LOGIC). This project is conducting deep phenotyping and genomic analyses in youth referred for neuropsychiatric evaluation. Using structural equation modeling, we examined whether EFs predicted variation in core dimensions of autism spectrum disorder, bipolar illness and schizophrenia, including social responsiveness, mania/emotion regulation, and positive symptoms of psychosis, respectively.

Results

We modeled three cognitive factors (working memory, shifting, and executive processing speed) that loaded on a second-order EF factor. The EF factor predicted variation in our three target traits but not in a negative control (somatization). Moreover, this EF factor was primarily associated with the overlapping (rather than unique) variance across the three outcome measures, suggesting it related to a general increase in psychopathology symptoms across those dimensions.

Conclusions

Findings extend support for the relevance of cognition to neuropsychiatric conditions that share underlying genetic risk. They suggest that higher-order cognition, including EFs, relate to the dimensional spectrum of each of these disorders and not just the clinical diagnoses. Moreover, results have implications for bottom-up models linking genes, cognition, and a general psychopathology liability.

Keywords: executive functions, mania, psychosis, social responsiveness, cross-disorder, dimensional traits

Introduction

Recent large-scale genomic analyses (Lee et al., 2013; PGC Cross Disorder Group, 2013) echo results from behavioral genetic and phenotypic modeling studies (Caspi et al., 2013; Lahey et al., 2012; Lichtenstein et al., 2009) in suggesting an underlying relationship between neuropsychiatric conditions that our current diagnostic system considers distinct. Such findings have implications for an improved understanding of shared risk mechanisms that could be targeted for intervention, as well as for a revised psychiatric nosology (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013) that acknowledges a general psychopathology liability. Phenotypes with relevance across multiple diagnoses are therefore important to study, as they could help to advance these lines of research.

Executive functions (EFs), including working memory, mental flexibility, verbal fluency, and inhibition, are promising candidates for further cross-disorder investigation. For example, in meta-analyses, individuals with schizophrenia (Fioravanti, Bianchi, & Cinti, 2012), bipolar disorder (Bourne et al., 2013), autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Geurts, van den Bergh, & Ruzzano, 2014) and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Alderson, Kasper, Hudec, & Patros, 2013; Lijffijt, Kenemans, Verbaten, & van Engeland, 2005) show EF decrements compared to controls. Yet, the conclusion that EFs are impaired in a wide range of neuropsychiatric conditions relies largely on extrapolation from separate studies that focused on single diagnoses. Although meta-analyses that have taken a multi-diagnostic approach suggest that EFs are indeed impaired across different conditions (Lipszyc & Schachar, 2010; Stefanopoulou et al., 2009; Willcutt, Sonuga-Barke, Nigg, & Sergeant, 2008), the limited number of investigations across disorders within the same sample (for an exception see David, Zammit, Lewis, Dalman, & Allebeck, 2008) has hindered direct examination of whether cross-disorder EF impairment could be an artifact of the comorbidity that is so common in psychiatry.

A second limitation of the prior literature is that studies have predominantly focused on categorical diagnoses. Yet, as highlighted by NIMH’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013), there is growing evidence for the dimensional nature of psychiatric illness. Whether EFs associate with quantitative dimensions relevant to different psychopathological conditions has only been examined to a limited extent, and, to our knowledge, has focused on relatively common conditions in youth that tend to be grouped within closely related domains of psychopathology (e.g., across different externalizing disorders - ADHD, conduct disorder and substance use; Castellanos-Ryan et al., 2014) or across different types of learning disorders (e.g., ADHD and dyslexia; McGrath et al., 2011).

In the current paper, we extend the examination of EFs and dimensions of psychopathology to aspects of severe and conceptually distinct conditions that have recently been found to share underlying genetic risk: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and ASD. Although the DSM-based diagnoses associated with these conditions are less common than other forms of psychopathology that have been modeled dimensionally in relation to EF, there is strong evidence that their symptoms also lie on a continuum (Constantino, 2009; van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, & Krabbendam, 2009). Moreover, twin and family data strongly implicate EFs in their underlying liability (Bora, Yucel, & Pantelis, 2009; Fombonne, Bolton, Prior, Jordan, & Rutter, 1997; Owens et al., 2011; Toulopoulou et al., 2007). Thus, given the prior literature, we hypothesized that EFs would associate with dimensions across these different conditions in a sample of youth referred for neuropsychiatric evaluation. Developing models of shared liability that include these phenotypes is important from a public health perspective, given that they relate to severe forms of psychopathology that can have a devastating impact on social and occupational functioning (Howlin, Savage, Moss, Tempier, & Rutter, 2014; World Health Organization, 2001).

Method

Participants

Participants were all youth enrolled in the Longitudinal Study of Genetic Influences on Cognition (LOGIC) at the time of analysis (n = 393) who were between the ages of 8:0 – 17:11. LOGIC is an ongoing project that combines deep cognitive and psychiatric phenotyping with genomic analyses in a clinical cohort of children and adolescents. The study ascertains consecutive, English-speaking referrals for a comprehensive neuropsychiatric evaluation at a pediatric assessment clinic within the Psychiatry Department at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. Patients are referred for documentation of cognitive and psychiatric strengths and weaknesses to aid in differential diagnosis and/or treatment planning. To enroll, participants must provide a DNA sample and access to their clinical data. Parents provide written informed consent, and youth provide written assent. Study procedures were approved by the MGH/Partners Institutional Review Board.

In order to amass dimensional psychiatric and cognitive phenotyping on a large clinical sample in a cost-efficient manner, study personnel supplement standardized assessments taking place in this clinical setting to cover an a priori designated set of cognitive and psychiatric dimensions. Diagnoses from the clinical record and demographic and cognitive features of the sample are provided in Table 1. Given the clinical nature of the sample, a portion of youth (45%) were taking psychotropic medication at the time of testing (see online supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Demographic, cognitive, and psychiatric features of the sample.

| Participant Characteristics N=393 |

M ± SD N (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age | 11.5 ± 2.7 |

| Sex; (N & % male) | 244 (62.1%) |

| Cognitive functions | |

| Full Scale IQ | 96.0 ± 16.2 |

| IQ Range | 41 – 135 |

| DSM-IV-TR Diagnosesa | |

| Autism Spectrum | |

| Asperger’s Syndrome | 27 (6.9%) |

| Autistic Disorder | 7 (1.8%) |

| Pervasive Developmental Disorder NOS | 67 (17.4%) |

| Mood Disorders | |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 40 (10.2%) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 14 (3.6%) |

| Mood Disorder NOS | 60 (15.3%) |

| Externalizing | |

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder | 208 (56.4%) |

| Anxiety Disorders | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 36 (9.2%) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 9 (2.3%) |

| Panic Disorder | 2 (0.5%) |

| Anxiety Disorder NOS | 97 (24.7%) |

| Learning Disorders | |

| Reading Disorder | 103 (26.2%) |

| Mathematics Disorder | 62 (15.8%) |

| Nonaffective Psychosis | |

| Schizophrenia | 0 (0%) |

| Psychosis NOS or prodromal symptoms | 19 (5.2%) |

Diagnoses shown are not mutually exclusive.

Executive functions and IQ

Table 2 shows the cognitive measures from our source study reflecting general intellectual ability and EFs. All measures were population-normed, have established reliability and validity, and are used in both research and clinical practice.

Table 2.

Study measures reflecting IQ and executive functions

| Cognitive Domains | Subtests | Source Test |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual Functions | ||

| Verbal Comprehension | Similarities | WISC-IV |

| Vocabulary | WISC-IV | |

| Comprehension | WISC-IV | |

| Perceptual Reasoning | Block Design | WISC-IV |

| Picture Concepts | WISC-IV | |

| Matrix Reasoning | WISC-IV | |

| Executive Functions | ||

| Working Memory | Digits Backwards | WISC-IV |

| Letter Number Sequencing | WISC-IV | |

| Fluency | Letter Fluency | D-KEFS |

| Shifting | Perseverative Errors | WCST |

| TMT (Switching) | D-KEFS | |

| Executive Processing Speed | Coding | WISC-IV |

| Symbol Search | WISC-IV | |

| TMT (Number sequencing) | D-KEFS | |

WISC-IV = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition (Wechsler, 2004); DKEFS= Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Holdnack, 2004); WCST=Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (2003); TMT = Trail Making Test (Delis et al., 2004).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Our CFA modeled core domains of EFs from previously established theoretical (Lesh, Niendam, Minzenberg, & Carter, 2011; RDoC Cognitive Group, 2011) and latent variable models (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). We modeled latent factors for working memory, shifting, and executive processing speed. Although processing speed is a distinct domain from EF, in practice, many processing speed measures, including those in the current battery, require working memory, attention, sequencing, abstract thinking, and the rapid coordination of these multiple functions. Because of the executive components of these tasks, we allowed for a relationship between EF and processing speed in our cognitive models (Cepeda, Blackwell, & Munakata, 2013). Finally, because a continuous performance test was added in the middle of the study, the resultant sample size for this measure did not permit its inclusion in the current analyses.

IQ

We used an average of the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) and Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) from the Wechsler scales to reflect general cognitive ability. We chose this composite rather than full-scale IQ because the latter includes Working Memory and Processing Speed and we were interested in examining these constructs separately.

Target psychopathology traits

Social responsiveness

The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Cronbach’s alpha >.90; Constantino & Gruber, 2005) was used to operationalize social communication impairments that represent core features of ASD. This parent-report questionnaire includes 65-items rated on a 4-point Likert scale.

Mania/emotional dysregulation

The Child Mania Rating Scale (CMRS) is a parent-report form that assesses emotional dysregulation and manic symptoms that are characteristic of bipolar illness. It consists of 21 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (Pavuluri, Henry, Devineni, Carbray, & Birmaher, 2006). The CMRS contains 3 positive symptoms of psychosis, which we dropped to eliminate overlap with the CSI scale (below). Our resultant CMRS measure (Cronbach’s alpha = .89) thus reflected the sum of all remaining items and was independent of psychosis.

Positive symptoms of psychosis

The Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI) is a parent-report rating scale that screens for behavioral and emotional symptoms reflecting a range of child psychiatric diagnoses (Gadow & Sprafkin, 2002). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The CSI assesses psychosis with five items (i.e., strange ideas or beliefs, auditory hallucinations, illogical thoughts/ ideas, laughs/cries inappropriately or shows no emotion, and does extremely odd things). We summed these items to create our psychosis scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .62).

Negative control

Somatization

We assessed a fourth neuropsychiatric dimension, somatization, as a negative control in order to determine the impact of method variance from parent reports. We chose this construct because there is minimal evidence of association between EFs and somatization in the literature (Niemi, Portin, Aalto, Hakala, & Karlsson, 2002); large-scale phenotypic modeling suggests that somatization is best conceptualized as separate from other aspects of psychopathology (Kotov et al., 2011); and somatization was evaluated via a questionnaire that was separate from those through which we assessed our target traits. Specifically, we assessed this construct using the Somatic Complaints scale from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; 6–18; Cronbach’s alpha = .78; Achenbach, 2009).

Analytic plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses were run with Mplus-version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2011) using maximum likelihood estimation and full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data. Missing data ranged from 6%–30% with covariance coverage exceeding 60% for all variables. Residual errors from closely related tasks (i.e., Trails Sequencing and Trails Switching) were permitted to correlate to allow for test-specific factors. Because χ2 tests are sensitive to sample size, we relied on the following fit indices and guidelines: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05, Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) <.08 (Loehlin, 2004). For comparing non-nested models, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were used as indices of absolute fit.

Our analytic plan consisted of six steps. First, we established the most parsimonious CFA of EFs. Second, we tested whether EFs predicted variation across the three different neuropsychiatric dimensions of interest. Third, in order to further understand the cognition-psychopathology relationship, we evaluated whether this prediction related primarily to the shared or unique variance among the neuropsychiatric dimensions. Fourth, we tested the robustness of the relationship between EFs and the psychopathology dimensions using covariate and multi-group analyses that accounted for sample variability in age, ADHD diagnosis, and medication use. Fifth, we separately evaluated the relationship between general cognitive ability (IQ) and the psychopathology outcomes. Finally, we tested the relationship between EFs and somatization as a negative control.

Data cleaning

All variables were continuously distributed, norm-referenced standardized scores except the CSI-psychosis and CMRS scales, which were derived for these analyses. For these latter variables, we tested for their association with age and gender. There were no significant associations, but there was a trend-level result for the CMRS correlating with age (r=−.12, p=.054), so here we used a residualized score in the analyses. Thus, all variables in the analyses were fully independent of age. Negative correlations were predicted between cognitive and psychopathology outcomes because high scores indicated better performance on cognitive tests but worse functioning on psychopathology scales (see Tables S2 and S3).

Each variable was inspected for normality, outliers (≥4 SD), and restricted range (see Table S4). Only the psychosis variable was notably positively skewed. Transformation did not fully normalize the distribution; however, follow-up models using a dichotomized version of the variable and the maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) suggested that the non-normal distributions did not unduly influence results.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis to model executive functions

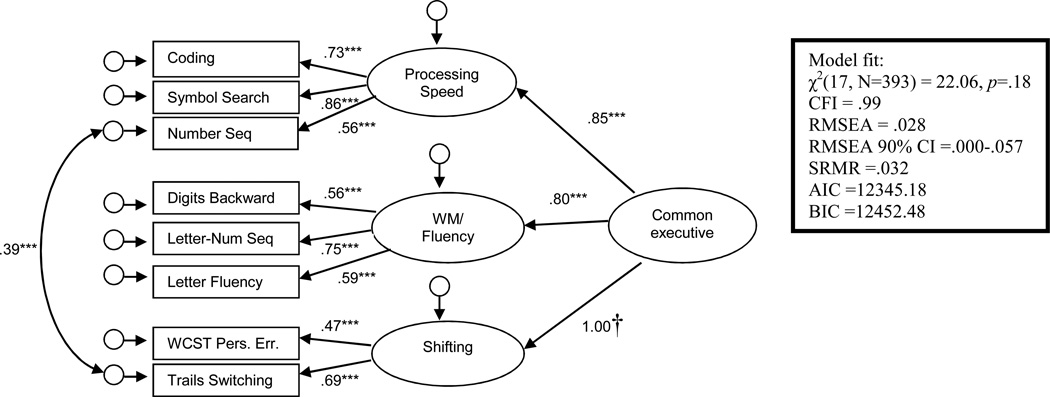

We considered two equivalent models, a first-order CFA (see online supplementary Figure S1) and a hierarchical CFA (see Figure 1) with identical and excellent fit statistics. Parsimony and high correlations among the latent factors (r = .68–.87) led us to select the hierarchical model for further analyses. In this model, shifting had a particularly high loading that could be fixed to 1 (standardized loading) without a significant decrease in model fit, Δχ2 = 0.11, Δdf =1, p = .74, which was not the case for the processing speed or working memory factor loadings (processing speed: Δχ2 = 12.51, Δdf =1, p <.001; working memory: Δχ2 = 15.38, Δdf =1, p <.001). This result indicated that the higher-order executive factor completely accounted for cognitive shifting ability, whereas the other two factors maintained non-overlapping variance with the factor. This hierarchical model fit the data better than a first-order, single-factor model in which all the indicators loaded on a single factor (see Figure S2), which supports the existence of a substructure underlying the over-arching EF domain. We use the term ‘common executive’ (CE) to refer to this higher-order construct, consistent with similar models by Miyake and colleagues (Friedman et al., 2008; Miyake & Friedman, 2012).

Figure 1.

Higher-order confirmatory factor analysis of the neurocognitive battery. Standardized factor loadings are depicted by single-headed arrows. * p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, † loading fixed to 1.

Relationship between executive functions and neuropsychiatric dimensions

The CE factor was significantly, though modestly, associated with each of our three target psychopathology outcomes (Figure 2). To further dissect this cross-domain prediction, we then examined whether the CE factor predicted the variance that was shared among the psychopathology outcomes by constructing a latent ‘general psychopathology’ factor. As depicted in Figure 3, the CE factor significantly predicted the general psychopathology factor, and there was good overall fit of the model. The CE accounted for about 6% of the variance in the general psychopathology factor (Figure 3) whereas it accounted for 2–3% of the variance in the psychopathology dimensions considered individually (Figure 2). The model restricting prediction to the shared variance among the psychopathology dimensions (Figure 3) was more parsimonious and yet not a worse fit to the data, indicating that there was minimal unique variance contributing to the prediction of each individual scale. Furthermore, additional models did not suggest that that the CE was significantly associated with the unique variance of any of the symptom dimensions. Rather, the relation between the CE factor and the psychopathology dimensions was primarily with the shared variance among the psychosis, mania, and social responsiveness symptom dimensions, despite the absence of shared symptoms among the scales.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of cross-domain prediction by the common executive factor. The measurement components of the model are not depicted for simplification. * p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, † loading fixed to 1.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model of the common executive as a predictor of shared variance among the quantitative psychopathology dimensions, which is captured by the general psychopathology latent factor. The measurement components of the model are not depicted for simplification. * p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, † loading fixed to 1.

To examine the potential influence of sample variability in age, diagnoses, and medication use, we conducted two sets of follow-up analyses, the first covarying for the effects of these factors and the second investigating potential moderating effects of these factors (see supplementary online Appendix S1). In the covariate analyses, we examined the impact of the most common psychiatric diagnosis in the sample (ADHD) and current psychotropic medication use (both for any medication and for stimulants, which were the most common type). Age was not included as a covariate because each of the cognitive and psychiatric variables was standardized by age, either within our sample or using test norms. Results showed that covarying for ADHD and medication/stimulant use did not reduce the strength of the relation between the CE factor and the general psychopathology factor (structural paths of −.25, −.27 in Figures S3 and S4, compared to −.24 in Figure 3). Next, we employed multi-group SEM to examine potential moderating effects of age, ADHD, and current psychotropic medication (both any and stimulant use) on the relation between the CE factor and the general psychopathology factor. Results showed that the structural path was statistically equivalent across all four grouping variables and comparable in effect size, even after accounting for minor differences in factor loadings between groups (see Tables S5 to S8). Accepting the limits of sample size for these multi-group analyses and the impossibility of proving the null hypothesis, these results support a stable relation between the CE factor and general psychopathology factor despite sample variability in age, ADHD, and psychotropic medication use.

Covariation with general cognitive ability

The CE factor was highly correlated with our IQ composite, r=.89, p<.001. Correlations between the IQ composite and the lower order EF factors were also strong (working memory/fluency r=.85, p<.001, shifting r=.86, p<.001, processing speed r=.65, p<.001). Collinearity prevented an examination of the relationship between the CE and the general psychopathology factor after controlling for IQ. Therefore, we compared the variance accounted for in the psychopathology outcomes when IQ vs. the CE factor was used as the predictor. IQ accounted for 1–3% of the variance in the individual psychopathology dimensions, which was comparable to the models with the CE. IQ accounted for a smaller amount of variance in the general psychopathology factor (4%) compared to the CE factor (6%). This modest difference could indicate slightly greater relevance of EF across different psychopathology constructs but could also reflect the stronger psychometric properties of the latent CE factor compared to the single indicator of IQ.

Specificity of the cross-domain prediction

We aimed to rule out parent-report halo effects by testing parent-reported Somatization, which we hypothesized would not significantly relate to EFs. This hypothesis was confirmed in a model where the CE was related to the CMRS, SRS, CSI-psychosis, and somatization scales simultaneously. Somatization was correlated with the other psychopathology scales (r’s ~.29–.30, p<.001) but was not significantly associated with the CE (standardized β =0.06, p=.32).

Discussion

In a consecutively referred child psychiatric cohort, variation in EFs predicted variation across social responsiveness, mania/emotional dysregulation, and positive symptoms of psychosis. These traits represent core features of autism spectrum disorder, bipolar illness, and schizophrenia, respectively, which are conditions that have recently been shown to share underlying genetic liability. These data extend a growing literature relating higher-order cognition to dimensional components of different forms of neuropsychiatric illness. Furthermore, they support consideration of EFs in studies aiming to clarify the risk mechanisms shared across different forms of psychopathology.

Cross-domain association between EFs and dimensional neuropsychiatric traits

By evaluating dimensional constructs, the current results build on a large prior literature that has predominantly considered EFs in relation to individual psychiatric diagnoses versus controls. Our study extends the small literature on psychopathology dimensions in two key ways. First, we specifically targeted symptoms of severe forms of neuropsychiatric illness which are rarely investigated dimensionally in relation to variation in EF. We specifically chose dimensions of autism spectrum disorder, bipolar illness, and schizophrenia because they have recently been confirmed to share underlying genetic risk. Previously, only a handful of studies have addressed EF in relation to dimensions across disorders, and these studies have included more prevalent conditions that tend to be grouped within closely related domains of psychopathology. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has extended an association with EF across dimensions of multiple, rare and severe neuropsychiatric conditions whose shared liability has been implicated in cross-disorder genetic studies. Such work represents an important step towards understanding the nature of this shared risk.

Second, by testing multiple psychopathology outcomes simultaneously, we show that EF was most strongly associated with the covariance of the dimensions, i.e. with a general increase in symptomatology across the three domains of social responsiveness, emotional regulation, and psychosis, represented as a ‘general psychopathology’ factor. Follow-up analyses indicated that the relationship between the CE factor and this general psychopathology factor was robust despite sample variability in age, ADHD, and medication use. Such a general psychopathology factor is consistent with recent empirically-derived models of the structure of psychopathology (Caspi et al., 2013; Lahey et al., 2012), and was labeled the ‘p factor’ by Caspi and colleagues (2013). Our findings suggest that there is a relationship between cognition and such a trait, at least as it relates to dimensions of ASD, mania, and psychosis.

Relevance to RDoC and a reconceptualized psychopathology

If replicated, the current data have implications for future studies that aim to use ‘cross-disorder’ genetic findings to develop revised models of psychopathology (Lee et al., 2013; PGC Cross Disorder Group, 2013). Currently, it is not known whether cross-disorder genetic variants act on a specific intermediate phenotype that increases risk for each disorder and/or whether the same set of genetic risk factors increases risk for different disorders in different people as a function of other genetic and environmental factors. Although these explanations are not mutually exclusive, it is important to identify potential mediators, because such phenotypes have implications for developmental models and early intervention. Our findings support consideration of models that integrate genes, aspects of higher-order cognition that include executive functions, and a general liability to psychopathology. These data could thus help to inform a psychiatric nosology constructed from the bottom up, such as promoted by NIMH’s RDoC (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013).

It is noteworthy that the association between EFs and psychopathology in our sample was significant but modest in magnitude (6% of variance). This result suggests that executive cognition may be only one of several risk factors that contribute to a general psychopathology liability. Nevertheless, a modest relation between cognition and psychopathology does not preclude a strong genetic contribution to their relationship (Owens et al., 2011; Toulopoulou et al., 2007). Thus even the modest variance explained may be fruitfully examined in future genetic studies.

In further studies, inclusion of other components of the EF construct, including inhibition, as well as overlapping constructs such as attention/vigilance may add to the variance explained in psychopathology, as could the examination of multiple traits relevant to particular psychopathological conditions of interest (e.g,. negative and positive symptoms of psychosis). Moreover, the models we developed could be extended to include common and frequently comorbid psychopathologic conditions (e.g. ADHD, anxiety, OCD) to broaden our understanding of a general psychopathology factor. Similarly, another important future direction is to clarify the relationship that specific learning disorders, such as dyslexia, have with both EFs and psychopathology. Nevertheless, for this study, we focused on variance shared by core symptom dimensions of severe conditions 1) that are considered distinct in our current diagnostic system; 2) that are now known to share aspects of their genetic etiology; and 3) and that have not been investigated in the same sample in relation to EFs. As such, documenting cognitive predictors of shared variance among these dimensions is quite novel.

Consistency with prior models of executive functions

Our EF measures overlap with primary models of the EF construct from the literature and tap aspects of cognitive control as represented in RDoC. As in our data, previous models of EF have specified an executive construct that wholly subsumes some sub-components but partially overlaps with others (Miyake & Friedman, 2012; RDoC Cognitive Group, 2011). Miyake and colleagues have described the ‘unity and diversity’ of EFs (Friedman et al., 2006; Miyake et al., 2000) which is consistent with our finding that the executive tasks clustered into a hierarchical factor structure. Our finding that the processing speed latent factor loaded highly on the CE factor is also consistent with the literature, showing that many processing speed measures for children are correlated with EFs (Cepeda et al., 2013; McGrath et al., 2011). Indeed, in earlier versions of the Wechsler IQ tests, the Coding and Digit Span tasks loaded on the same factor (Wechsler, 1974). In line with these findings, our study found that the correlations between the executive processing speed factor with more ‘classic’ EF constructs, such as shifting and working memory, were comparable to the correlations of the EF constructs with each other. This result highlights the challenges of ‘task impurity’ when measuring complex cognitive processes and points to the utility of latent factor models in isolating shared variance amongst diverse tasks.

Overlap with IQ

There is strong evidence that EF and general cognitive ability overlap both conceptually (Diamond, 2013) and neuroanatomically (Colom et al., 2013) but are nonetheless separable constructs. While it was our intention to examine whether EFs associate with neuropsychiatric symptomatology independent of general cognitive ability, we were not able to disentangle these constructs in our dataset. The individual factors were more highly correlated with each other (r~ .7–.9) and with IQ (r=.89) than in previous studies using similar latent models with more circumscribed cognitive neuroscience measures of EF (Friedman et al., 2006). It is possible that the use of subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence battery across the constructs of IQ and EF contributed to their higher correlation through method variance. It may also be the case that the clinical nature of the sample inflated the correlations among our cognitive measures, as children with multiple cognitive problems are more likely to come to clinical attention. Further work with more precise measures of EF is needed to disentangle the predictive value of the shared and unique variance between EF and IQ as it relates to psychopathology. Nonetheless, our data extend the literature by showing that aspects of higher order cognition are related to several dimensions of severe neuropsychiatric illness and possibly general psychopathology risk.

Methodological considerations and limitations

While a potential concern regarding our selection of psychopathology dimensions is that diagnoses of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia occurred at low base rates in this sample, our focus on quantitative dimensions of psychopathology is predicated on variance rather than diagnostic rates. This neuropsychiatrically referred sample had evidence of relevant subclinical psychopathology as indicated by high rates of NOS mood diagnoses (15%) and, in the case of psychosis, the fact that 34% and 22% of the sample endorsed 1 or more or 2 or more positive symptoms, respectively. Thus, the quantitative variation in the sample was robust.

We took several steps to rule out the impact of method and measurement variance on the relation between cognition and psychopathology. As noted, our three target measures were based on parental reports. While method variance from parent report requires consideration, parents are critical informants for youth samples in clinical and research practice. By showing that cognition was not significantly associated with somatization, which lacks a strong link to EFs (Niemi et al., 2002), we provided evidence that the relationship between the CE and the general psychopathology factor was not simply a ‘halo effect’ of parental reports (Cooper, 1981). Additionally, we removed overlapping items from the scales and used traits from distinct questionnaires to diminish the impact of common measurement variance on cross-domain predictions.

Our findings should, however, be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, given our use of a clinical sample, our results cannot be presumed to reflect the relationship between cognition and psychopathology in the general population. Still, this possibility warrants consideration, as there is precedent in the literature for similarity between the structure of psychopathology in outpatient clinical cohorts and more representative samples (Kotov et al., 2011). Nevertheless, our sample is unique and useful for the purposes of these analyses in that it manifests considerable variation across cognitive and psychiatric phenotypes that have not previously been modeled together in the literature. Further, it allows us to address the relationships between EF and dimensions of severe neuropsychiatric illness in youth who present for clinical evaluation. Gaining a better understanding of these relationships in clinical samples may help to refine targets for intervention. For example, it has been hypothesized that interventions that remediate cognition may improve psychopathological outcomes (Insel, 2010), and this possibility would be worthy of further consideration if evidence for the relationship between EF and a range of neuropsychiatric symptomatology continues to grow. Of course, due to the cross-sectional nature of our project, we cannot rule out the possibility that variation in EF is actually a sequela of psychopathology; however, studies of unaffected relatives of individuals with diagnoses relevant to our analyses suggest that cognition is more likely relevant to underlying liability and thus important to consider in studies aiming to elucidate risk.

A second issue regarding the clinical nature of the sample is the potential for restricted range of cognitive and psychiatric measures, such that the sample may have over-representation of moderately to severely affected children. We do not believe restricted range was a serious concern because the standard deviations of norm-referenced tests were largely the same as population samples. Nevertheless, if restricted range did influence the results, we note that it would make it more difficult to detect a relationship between higher-level cognition and the psychiatric dimensions, thereby suggesting that our results may have underestimated the relationship.

Third, we acknowledge that examining relationships between cognition and psychopathology in a medication naïve sample would be beneficial, but we also note that such a sample would have compromised external validity. We comprehensively examined the impact of medication use on our findings through covariate and moderator analyses and to the extent possible, ruled out the confounding effects of medication use in this sample.

Finally, incorporation of additional measures grounded in cognitive neuroscience could strengthen our measurement of EF domains and determine their separable contribution to our outcomes over and above IQ, which we were not able to do. Nonetheless, the measures we employed are relevant to the prior literature on which we are building, are widely-used in clinical practice with children, and have the advantage of well-established reliability and validity in youth samples. Thus, they provide an important first step in our inquiry into the role of higher-order cognitive processes in cross-disorder mechanisms.

Conclusions

In clinically-referred children and adolescents, variation in EFs predicted variation in quantitative traits from three different psychopathological conditions that share genetic risk. Importantly, EFs were associated with the shared variance among the traits, suggesting a relationship with a general psychopathology construct. These data justify further studies that can clarify relationships between specific genetic pathways, executive cognition, and diverse presentations of psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Executive functions (EFs) are impaired in different neuropsychiatric conditions that share genetic liability; however, the prior literature rests largely on separate studies of single diagnoses rather than dimensional models of psychopathology in multi-diagnostic cohorts.

In 393 clinically-referred youth, we determined that EFs were associated with dimensional measures of the autism spectrum, mania and psychosis. Here, EF was associated with a general increase in psychopathology symptoms across these measures.

These data extend the cross-disorder relevance of cognition to dimensions of psychopathology. They further suggest that EFs should be included in studies aiming to understand how genetic risk influences different forms of psychopathology.

Clinically, children with poor EF are at increased risk for multiple types of psychopathological symptoms that cross diagnostic boundaries.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research and R03 MH106862 (to A.E.D.), an American University faculty research support grant (to L.M.M.), and the David Judah Foundation (to A.E.D. and E.B.B.). The authors wish to thank Pieter Vuijk for his comments on this manuscript. Author R.P. consults to or serves on scientific advisory boards for Genomind, Healthrageous, Pamlab, Perfect Health, Pfizer, Proteus Biomedical, Psybrain, and RIDVentures. The author receives royalties from UBC, a Medco subsidiary. In the past year, author S.F. received consulting income, travel expenses and/or research support from Akili Interactive Labs, Alcobra, VAYA Pharma, and SynapDx and research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The author’s institution is seeking a patent for the use of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitors in the treatment of ADHD. In previous years, the author received consulting fees or was on Advisory Boards or participated in continuing medical education programs sponsored by Shire, Alcobra, Otsuka, McNeil, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. The author receives royalties from books published by Guilford Press: Straight Talk about Your Child’s Mental Health and Oxford University Press: Schizophrenia: The Facts. Author J.S. serves on the scientific advisory board of PsyBrain. The author receives support from NIMH, the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, and the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation.

Footnotes

Dr. Seidman reports no competing interests. All other authors declare that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interests.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix 1. Methods and Results: Description of sample stratification analyses.

Table S1. Psychotropic medications in patients in the sample.

Table S2. Correlations among study measures

Table S3. Correlations among the latent factors.

Table S4. Descriptives for cognitive and psychiatric measures

Table S5. Multigroup CFA and SEM analyses by age group (younger 8–11 years; older 12–17 years)

Table S6. Multigroup CFA and SEM analyses by ADHD diagnosis.

Table S7. Multigroup CFA and SEM analyses by current psychotropic medication status.

Table S8. Multigroup CFA and SEM analyses by current stimulant medication status.

Figure S1. Confirmatory factor analysis of our neurocognitive battery.

Figure S2. Single factor model of our neurocognitive battery.

Figure S3. Structural equation models accounting for covariates: ADHD diagnosis (yes/no) and any current psychotropic medication use (yes/no).

Figure S4. Structural equation models accounting for covariates: ADHD diagnosis (yes/no) and current stimulant use (yes/no).

References

- Achenbach TM. ASEBA: Development, findings, theory and applications. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alderson RM, Kasper LJ, Hudec KL, Patros CH. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and working memory in adults: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2013;27(3):287–302. doi: 10.1037/a0032371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(1–2):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne C, Aydemir O, Balanza-Martinez V, Bora E, Brissos S, Cavanagh JT, Goodwin GM. Neuropsychological testing of cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar disorder: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128(3):149–162. doi: 10.1111/acps.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Moffitt TE. The p Factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan N, Struve M, Whelan R, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, Bokde AL, Conrod PJ. Neural and cognitive correlates of the common and specific variance across externalizing problems in young adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(12):1310–1319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda NJ, Blackwell KA, Munakata Y. Speed isn't everything: complex processing speed measures mask individual differences and developmental changes in executive control. Dev Sci. 2013;16(2):269–286. doi: 10.1111/desc.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom R, Burgaleta M, Roman FJ, Karama S, Alvarez-Linera J, Abad FJ, Haier RJ. Neuroanatomic overlap between intelligence and cognitive factors: morphometry methods provide support for the key role of the frontal lobes. Neuroimage. 2013;72:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN. How continua converge in nature: cognition, social competence, and autistic syndromes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(2):97–98. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318193069e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale. Los Angeles: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WH. Ubiquitous halo. Psychol Bull. 1981;90(2):218–244. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 2013;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David AS, Zammit S, Lewis G, Dalman C, Allebeck P. Impairments in cognition across the spectrum of psychiatric disorders: evidence from a Swedish conscript cohort. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1035–1041. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Holdnack J. Reliability and validity of the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System: an update. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(2):301–303. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti M, Bianchi V, Cinti ME. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: an updated metanalysis of the scientific evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Bolton P, Prior J, Jordan H, Rutter M. A family study of autism: cognitive patterns and levels in parents and siblings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(6):667–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, Miyake A, Corley RP, Young SE, Defries JC, Hewitt JK. Not all executive functions are related to intelligence. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(2):172–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, Miyake A, Young SE, Defries JC, Corley RP, Hewitt JK. Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2008;137(2):201–225. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow, Sprafkin . Child Symptom Inventory- Fourth Edition: Screening and norms manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts HM, van den Bergh SF, Ruzzano L. Prepotent Response Inhibition and Interference Control in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Two Meta-Analyses. Autism Res. 2014 doi: 10.1002/aur.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Savage S, Moss P, Tempier A, Rutter M. Cognitive and language skills in adults with autism: a 40-year follow-up. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):49–58. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Ruggero CJ, Krueger RF, Watson D, Yuan Q, Zimmerman M. New dimensions in the quantitative classification of mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1003–1011. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, Rathouz PJ. Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(4):971–977. doi: 10.1037/a0028355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Ripke S, Neale BM, Faraone SV, Purcell SM, Perlis RH, Wray NR. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat Genet. 2013;45(9):984–994. doi: 10.1038/ng.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(1):316–338. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Bjork C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, Hultman CM. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373(9659):234–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lijffijt M, Kenemans JL, Verbaten MN, van Engeland H. A meta-analytic review of stopping performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: deficient inhibitory motor control? J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(2):216–222. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipszyc J, Schachar R. Inhibitory control and psychopathology: a meta-analysis of studies using the stop signal task. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(6):1064–1076. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural equation analysis. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- McGrath LM, Pennington BF, Shanahan MA, Santerre-Lemmon LE, Barnard HD, Willcutt EG, Olson RK. A multiple deficit model of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: searching for shared cognitive deficits. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):547–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP. The Nature and Organization of Individual Differences in Executive Functions: Four General Conclusions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21(1):8–14. doi: 10.1177/0963721411429458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex ‘Frontal Lobe’ tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000;41(1):49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 6th. Los Angeles, CA.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi PM, Portin R, Aalto S, Hakala M, Karlsson H. Cognitive functioning in severe somatization--a pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(6):461–463. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens SF, Rijsdijk F, Picchioni MM, Stahl D, Nenadic I, Murray RM, Toulopoulou T. Genetic overlap between schizophrenia and selective components of executive function. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Devineni B, Carbray JA, Birmaher B. Child mania rating scale: development, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(5):550–560. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205700.40700.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PGC Cross Disorder Group. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RDoC Cognitive Group. Cognitive Systems: Workshop Proceedings. Rockville, MD.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Resources PA. In: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test- Computerized Version. Psychological Assessment Resources, editor. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanopoulou E, Manoharan A, Landau S, Geddes JR, Goodwin G, Frangou S. Cognitive functioning in patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):336–356. doi: 10.1080/09540260902962149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulopoulou T, Picchioni M, Rijsdijk F, Hua-Hall M, Ettinger U, Sham P, Murray R. Substantial genetic overlap between neurocognition and schizophrenia: genetic modeling in twin samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1348–1355. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179–195. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Weschsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (WISC-R) New York: Psychological Corporation; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Wechsler intelligence scale for children—Fourth edition. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt E, Sonuga-Barke E, Nigg J, Sergeant J. Recent developments in neuropsychological models of childhood psychiatric disorders. In: Banaschewski T, Rohde L, editors. Biological Child Psychiatry: Recent Trends and Developments. Vol. 24. Basel, Karger: 2008. pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva: 2001. World Health Report: new understanding, new hope. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.