Abstract

Persistent elevation of Ca2+ influx due to prolongation of the action potential (AP), chronic activation of the β-adrenergic system and molecular remodeling occurs in stressed and diseased hearts. Increases in Ca2+ influx are usually linked to prolonged myocyte action potentials and arrhythmias. However, the contribution of chronic enhancement of Cav1.2 activity on cardiac electrical remodeling and arrhythmogenicity has not been completely defined and is the subject of this study. Chronically increased Cav1.2 activity was produced with a cardiac specific, inducible double transgenic (DTG) mouse system overexpressing the β2a subunit of Cav (Cavβ2a). DTG myocytes had increased L-type Ca2+ current (ICa-L), myocyte shortening, and Ca2+ transients. DTG mice had enhanced cardiac performance, but they died suddenly and prematurely. Telemetric electrocardiograms revealed shortened QT intervals. The action potential duration (APD) were shortened in DTG myocytes due to significant increases of potassium currents and channel abundance. However, shortened AP in DTG myocytes did not fully limit excess Ca2+ influx and increased the peak and tail ICa-L. Enhanced ICa promoted sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ overload, diastolic Ca2+ sparks and waves, and increased NCX activity, causing increased occurrence of early and delayed afterdepolarizations (EADs and DADs) that may contribute to premature ventricular beats and ventricular tachycardia. AV blocks that could be related to fibrosis of the AV node were also observed. Our study suggests that increasing ICa-L does not necessarily result in AP prolongation but causes SR Ca2+ overload and fibrosis of AV node and myocardium to induce cellular arrhythmogenicity, arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities.

Keywords: L-type calcium channel or Cav1.2, β2a subunit, afterdepolarizations, short QT, potassium currents

Introduction

Cardiac arrhythmias are a significant contributor to premature death in the United States. Aberrant Ca2+ homeostasis and electrical remodeling are central to cardiac arrhythmias [1, 2] . Altered properties of the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC or Cav1.2) plays important roles in cardiac arrhythmias because it is linked to both the electrical properties and Ca2+ homeostasis [2]. The L-type Ca2+ current (ICa-L) determines the duration of the action potential and provides the source of Ca2+ for loading the sarcoplasmic (SR) [2, 6]. β-adrenergic stimulation [2, 12] or gene mutations [20] or changes of the subunit composition [21] of the L-type Ca2+ channel may increase the activities of the LTCC. The dogma is that increases in ICa-L cause the prolongation of the action potential duration (APD) and SR Ca2+ overload in patients [2] and animals[15]. While action potential prolongation provides a substrate for early afterdepolarizations (EADs), spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR with Ca2+ overload induces delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs). Both EADs and DADs are triggers for cardiac arrhythmias [17]. AP prolongation and increased Cav1.2 activity may lead to reopening of Cav1.2 during the plateau of APs to induce EADs. Mutations of Cav1.2 that increase Cav1.2 activity induce a long QT syndrome in human [20]. Increases in Ca2+ influx elevate cytosolic and SR Ca2+, which could decrease the expression of the transient outward potassium channels [28]. However, the resultant remodeling of electrical properties and Ca2+ handling of myocytes when Cav1.2 activity is chronically increased has not been fully characterized and is the topic of this study.

To simulate increases in Cav1.2 activity, we overexpressed the β2a subunit of Cav (Cavβ2a) in a cardiac specific and inducible manner in mice [25]. In this transgenic (TG) mouse system, overexpression of Cavβ2a elicited the same modulatory effect on Cav1.2 activity (mode 2) as does phosphorylation of Cav1.2. Along with increased Ca2+ influx into cardiomyocytes and enhanced cardiac contractility in Cavβ2a TG mice, the QT intervals and ventricular myocyte APDs were decreased, in contrast to prolonged QT and APD typically observed with increased Cav1.2 activity [20]. This is because of compensatory increases in potassium currents due to increased expression of multiple potassium channels. On top of shortened APs, EADs and DADs were still detected, which could be associated with increased peak and tail ICa-L, high SR Ca2+ load and leak, and increased NCX activity in Cavβ2a TG myocytes. Telemetric ECG showed prolonged QRS duration and RR intervals, AV blocks, premature ventricular contraction, and non-sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in DTG mice which could be related to SR Ca2+ overload, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Our study suggests that the increases in the L-type Ca2+ channel activity do not necessarily prolong the action potential but cause SR Ca2+ overload and myocardial fibrosis to induce EADs, DADs, arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities, at least in mice.

Methods

Detailed method description is included in the supplemental material. A transgenic mouse line overexpressing Cavβ2a at relatively low expression level was used for this study [25] (Supplemental Figure 1). Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University.

Left ventricular myocytes (LVMs) were isolated and whole cell L-type Ca2+ current (ICa-L), sodium-calcium exchange current (INCX) was measured [25]. Action potentials (APs), and Ca2+-insensitive potassium currents were measured in myocytes from the midwall of the free wall of the left ventricle [13]. Diastolic Ca2+, Ca2+ transients and SR Ca2+ load were measured with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicators indo-1-AM or Fluo-4 AM[25]. Line scan Ca2+ transients were also recorded by confocal (LSM510 confocal microscope, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) line scanning [33]. ECHO was performed with a VisualSonics Vevo 770 machine [35]. Implanted ETA-F20 telemetric transmitters (DSI, St. Paul, MN) were used to record ECG in 6-month old mice. Masson’s trichrome staining was performed to determine fibrosis [25]. Western blot procedure was performed to detect protein abundance. Twenty control and twenty DTG mice receiving standard care by the Central Animal Facility at Temple University were observed daily during a 12-month period for survival.

Data are reported as mean±SEM. Paired and unpaired T-test, Kaplan-Meier’s survival test and contingency table analysis for incidence rates were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0. ANOVA or ANOVA for repeated measures were used to detect significance with SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A p value of ⩽ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

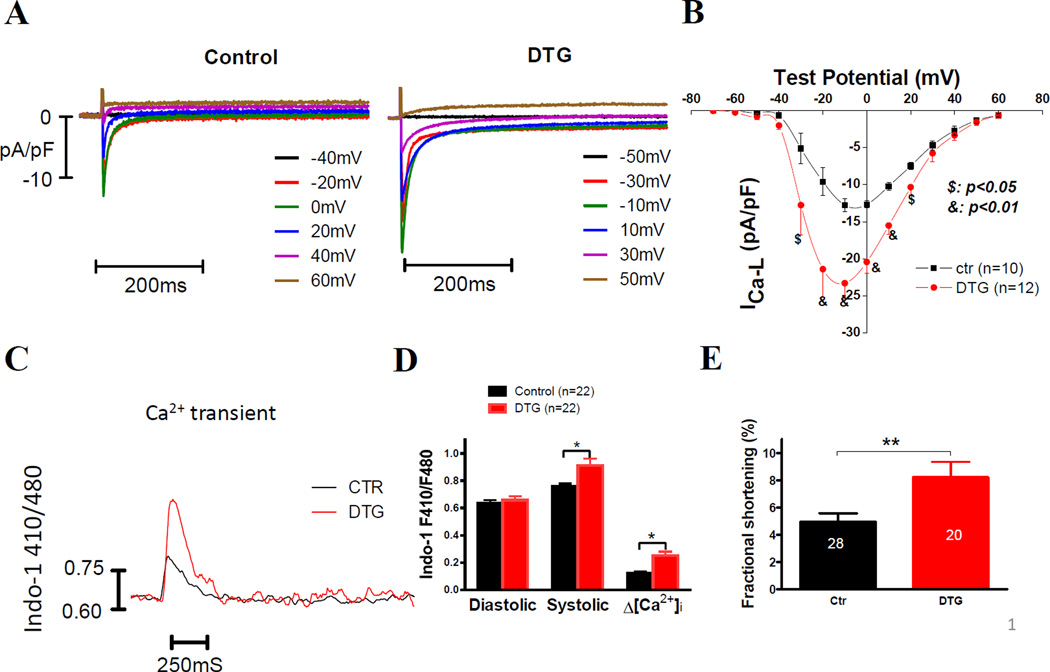

Cavβ2a overexpression increased ICa-L, Ca2+ transient amplitudes, and contractions in VMs

In myocytes isolated from 6-month old DTG mice, we found that ICa-L was significantly increased by 82.0% versus wild-type mice (maximum ICa-L: control 12.8±0.8pA/pF vs. DTG 23.2±2.2pA/pF) (Figure 1A and B). The amplitudes of Ca2+ transients and contractions induced by field stimulation at 0.5Hz were also significantly increased, while the diastolic Ca2+ concentration was not altered in the DTG myocytes (Figure 1C–E). These data agree with our previous study in 4-month old DTG [25].

Figure 1. DTG myocytes have greater ICa-L density and enhanced contractility.

(A) Raw ICa-L recordings in a control VM and a DTG VM. (B) Current-voltage (I–V) relationships of ICa-L in control (ctr, n=10, N=3) and DTG (n=12, N=3) VMs. (C) Examples of Ca2+ transients in a control and a DTG VM. (D) Diastolic, systolic and the amplitude of [Ca2+]i measured with indo-1 in control and DTG VMs recorded at 0.5Hz, showing no difference in diastolic but increased systolic and amplitudes of [Ca2+]i in DTG VMs. (E) Greater myocyte contraction expressed as fractional shortening was observed in DTG VMs. $: p<0.05, &: p<0.01, control vs. DTG at the same test potential, two-way ANOVA with post-hoc t tests; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01 control vs. DTG, student t-test. “n” cells from “N” animals were studied.

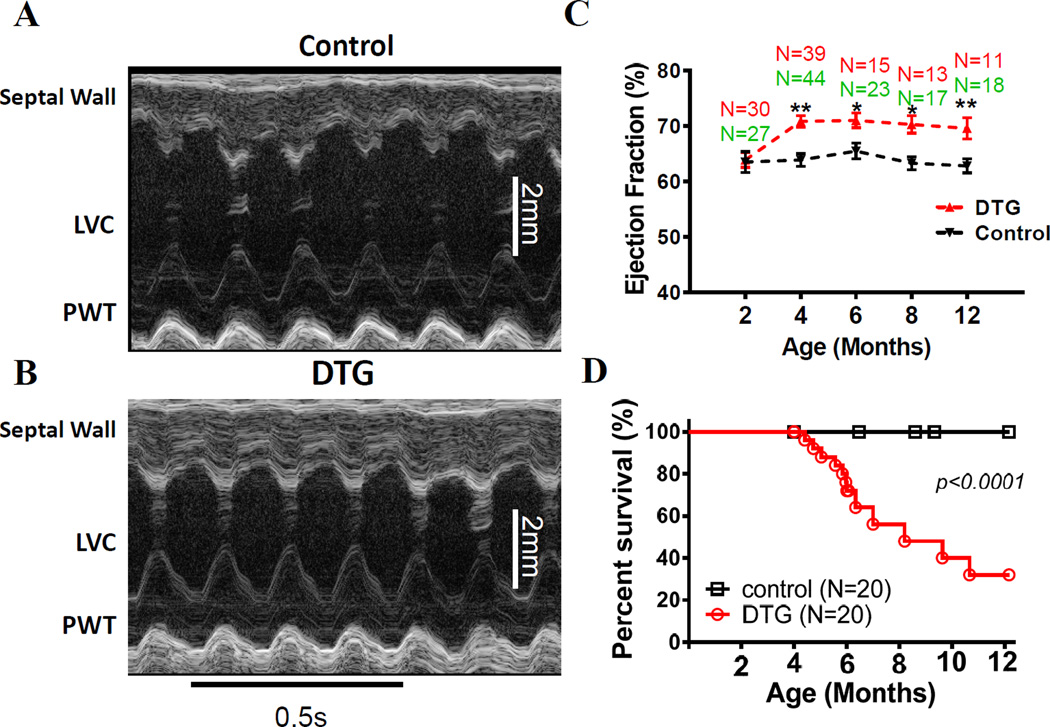

Cavβ2a DTG mice had enhanced cardiac function but died prematurely and suddenly

Consistent with increased myocyte function in DTG hearts, DTG hearts had enhanced function (ejection fraction) than WT hearts during the 4–2 months of life (Figure 2A–C). However, DTG mice began to die suddenly after the age of 4 months, which corresponds to the time when Cavβ2a expression is detectable [25] (Figure 2D). These data show that DTG mice did not die from depressed cardiac function, and suggest an arrhythmic mechanism for the sudden death.

Figure 2. DTG mice have hypercontractile hearts but die suddenly after transgene expression.

(A) & (B) Examples of M-mode images of echocardiography of a control mouse (A) and a DTG (B) mouse at the age of 6 months. (C) Ejection fractions (EF) of control and DTG mice from the age of 2 months to 12 months, showing cardiac hypercontractility in DTG mice at ages ⩾ 4 months. *: p<0.05 DTG vs. control; **: p<0.01 DTG vs. control; (D) Kaplan-Meier’s survival test of control and DTG mice. N: numbers of animals studied.

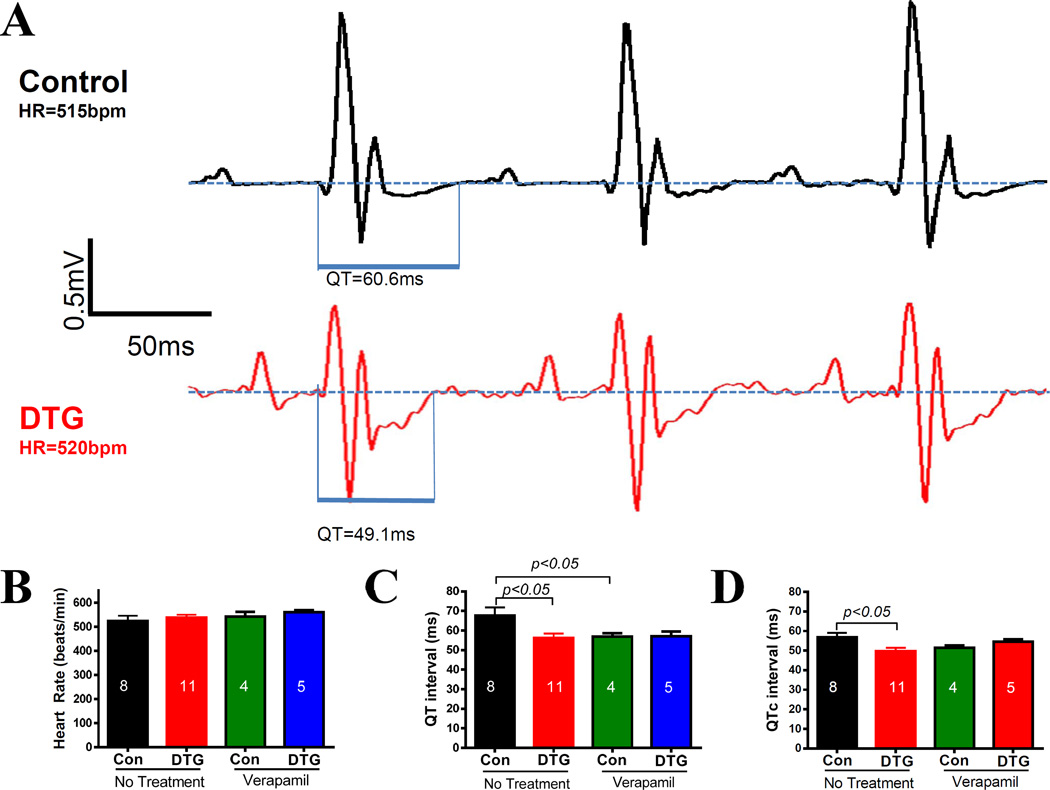

Cavβ2a DTG mice had shortened QT intervals

Telemetric ECGs showed that the QT interval and heart rate corrected QT interval (QTc) were significantly shorter in DTG with increased ICa-L than in control mice (Figure 2), which is opposite to the anticipated longer QT interval usually seen with gain of function of Cav1.2 in humans [20]. After the control and DTG mice were treated with verapamil for 8 weeks since the age of 4 months, QT and QTc were not different between control and DTG mice although in both groups of animals, QT and QTc were shortened due to the blockade of the L-type channel by verapamil (Figure 3 C and D).

Figure 3. DTG mice have shortened QT intervals that are normalized by verapamil.

(A) Examples of telemetric ECGs recorded from a control and a DTG mice. QT durations are indicated. (B) DTG and control mice with or without verapamil treatment have similar heart rates. (C) & (D) QT intervals (C) and corrected QT intervals (D) are shorter in DTG than in control mice but verapamil treatment shortened QT and QTc to the same in both groups of animals. The numbers in the bars are numbers of animals studied.

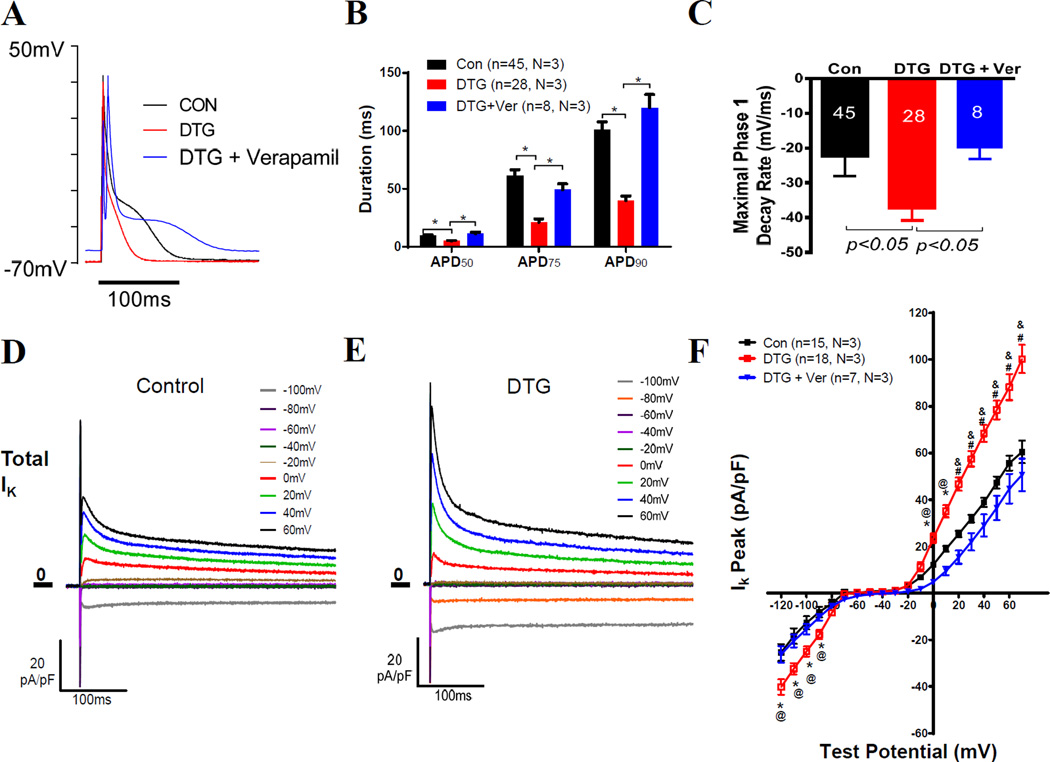

Cavβ2a DTG myocytes had shorter action potentials due to increased potassium currents

QT interval represents the average AP duration of ventricular myocytes. Therefore, APs were measured in isolated VMs to determine the bases of the shortened QT intervals [20]. While there was no significant difference in resting membrane potentials (control vs. DTG: −66.6±1.5mV vs. −65.3±2.1mV, without correction for the junction potential) and the overshoot amplitudes of the action potentials (control vs. DTG: 26.6±3.8mV vs. 30.6±3.3mV, without correction for the junction potential), APD50, APD75 and APD90 were significantly shorter in DTG myocytes than in control myocytes (Figure 4A and B). The maximal phase 1 decay rate, an index of transient outward potassium current (Ito), was significantly increased in DTG myocytes (Figure 4C). These alterations of action potentials in DTG myocytes were normalized by feeding the DTG mice with verapamil (Figure 4 A–C), suggesting these changes were induced by increased Ca2+ influx rather than a direct effect of the overexpressed Cavβ2a.

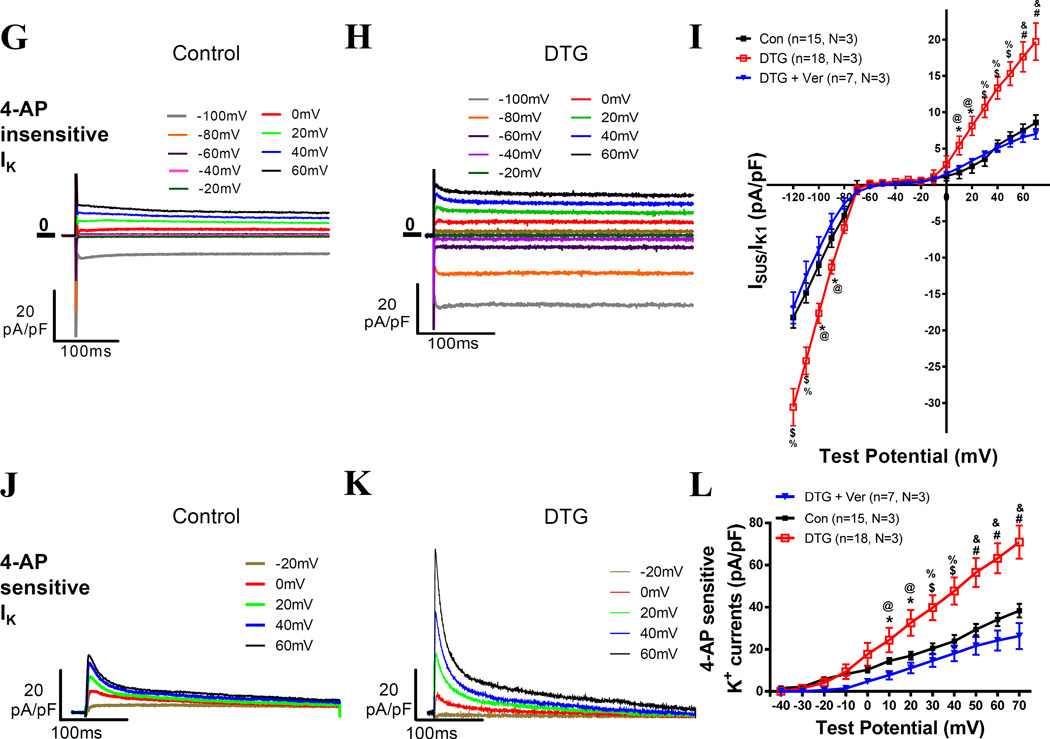

Figure 4. DTG myocytes have shortened AP duration and increased potassium currents that can be reversed by verapamil treatment.

(A–C) Typical APs (A), AP durations (APDs) (B), and maximal phase 1 decay rates of APs (C) recorded in VMs from control, DTG and DTG with verapamil treatment mice. (D) & (E) Examples of total Ik recorded in control and DTG VMs. (F) Averaged Ik peak in VMs of control, DTG and DTG+verapamil animals at different testing potentials. (G) & (H) Examples of 4-AP-insenstive K+ currents from a control and a DTG myocytes. (I) Averaged sustained 4-AP insensitive K+ currents in VMs of control, DTG and DTG+verapamil animals at the end of the 4s at different test potentials. (J) & (K) Examples of 4-AP-senstive K+ currents from a control VM and a DTG VM. (L) Averaged 4-AP sensitive K+ currents in VMs of control, DTG and DTG+verapamil animals at different test potentials. In F, I and L*: p<0.05 DTG vs. control; $: p<0.01 DTG vs. control; #: p<0.001 DTG vs. control; @: p<0.05 DTG vs. DTG+verapamil; %: p<0.01 DTG vs. DTG+verapamil; %: p<0.001 DTG vs. DTG+verapamil. Repeated two-way ANOVA with post-hoc t-test (15 control VMs from 3 control mice; 18 DTG VMs from 3 DTG mice, 7 VMs from 3 verapamil treated DTG mice).

The balance between depolarizing ICa-L and repolarizing potassium currents determines APD [5], and we observed shortened APDs even though ICa-L was increased in DTG VMs. Therefore, we anticipated increased outward K+ currents (Ik) in DTG myocytes. The peak amplitude of total Ik was significantly greater in DTG VMs than in control VMs (Figure 4D, E and F). The 4-AP insensitive Isus/Ik1 [26] density in DTG VMs was greater than in control VMs (Figure 4G–I). The 4-AP sensitive potassium currents (mostly Ito and Ik,slow1) [26] density was also greater in DTG VMs than in control VMs at test potentials >0mV (Figure 4 J–L). The increases in both 4- AP sensitive and insensitive potassium currents suggest that chronically elevated Ca2+ influx induces a compensatory upregulation of multiple potassium channel currents. The increases of total K+ currents, 4-AP insensitive K+ currents and 4-AP sensitive K+ currents in DTG myocytes were normalized by treating DTG mice with verapamil (Figure 4 F, I and L), arguing against a direct modulatory effect of overexpressed Cavβ2a on K+ channel expression.

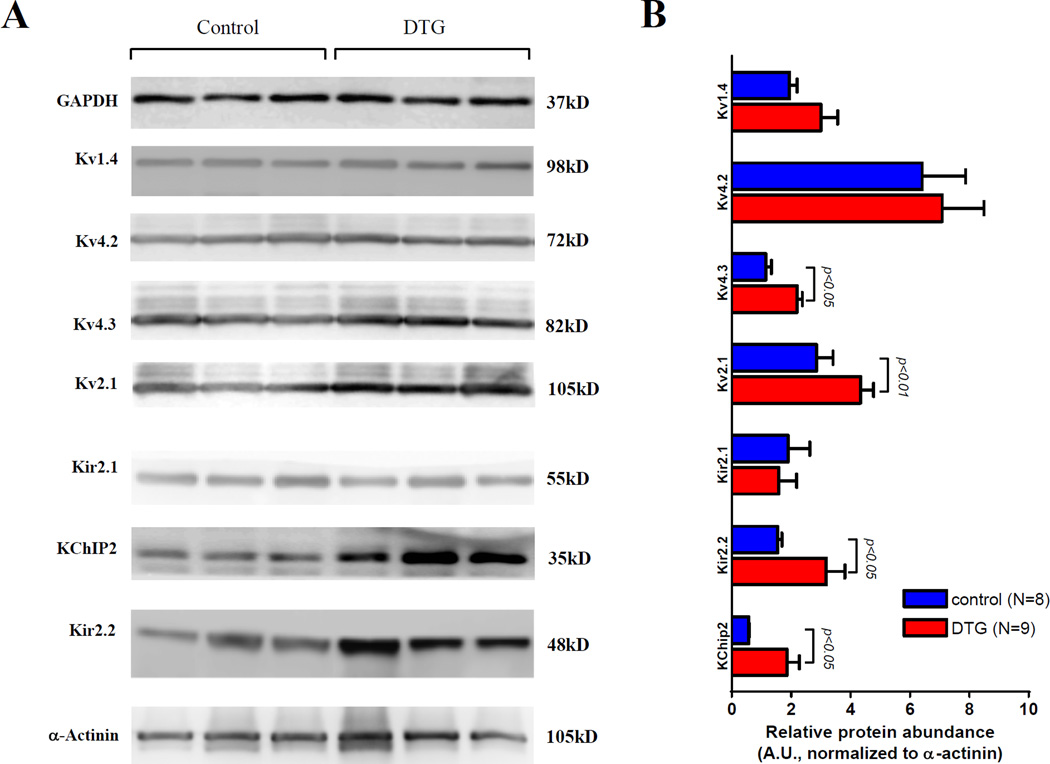

Multiple genes encode the channels that mediate Ito: KCNA4 encodes Kv1.4 (Ito,s); KCND2 and KCND3 encode Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 (Ito,f), respectively; the accessory subunit KCNIP2 encodes KChIP2 [26]. In DTG hearts, the expression of distinct Ito channels was differentially regulated by enhanced Ca2+ influx. The protein abundance of Kv4.3 and KChIP2 were significantly increased (Figure 5). Kv1.4 and Kv4.2 protein abundances were not altered. These data suggest that the increased Ito was primarily due to elevated abundance of Kv4.3 and KChIP2. The abundance of Kv2.1, which mediates IK,slow, was also significantly increased (Figure 5). Ik1 is mediated by Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 channels in mouse hearts. In the DTG hearts, the protein abundance of Kir2.1 was not changed but Kir2.2 was significantly increased (Figure 5), indicating that the increase in Kir2.2 abundance accounts for the larger Ik1 in DTG myocytes.

Figure 5. The expression of potassium channels in control (N=8) and DTG (N=9) hearts.

Representative Western blots of Kv1.4, Kv4.2, Kv4.3, Kv2.1 and Kir2.1 and KChiP2 and Kir2.2 (A) are shown. The averaged expression level was normalized to sarcomeric a-actinin (B).

Shortened AP did not effectively limit Ca2+ influx but increased ICa peak and tail currents in Cavβ2a DTG myocytes

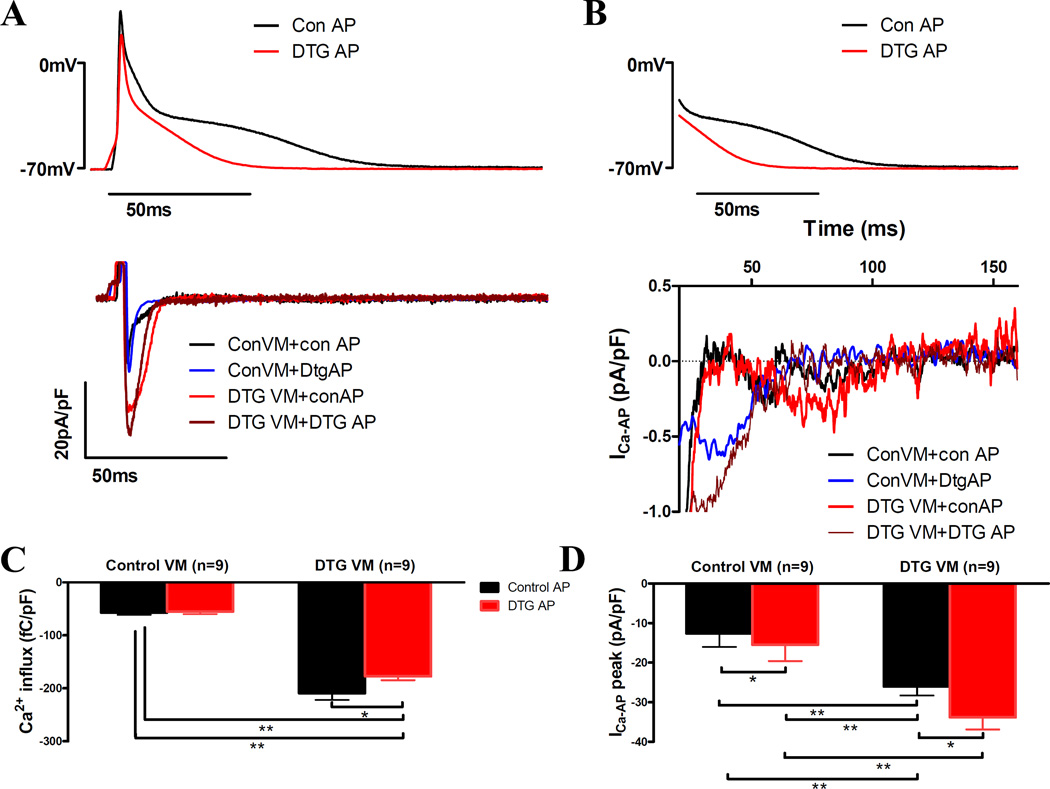

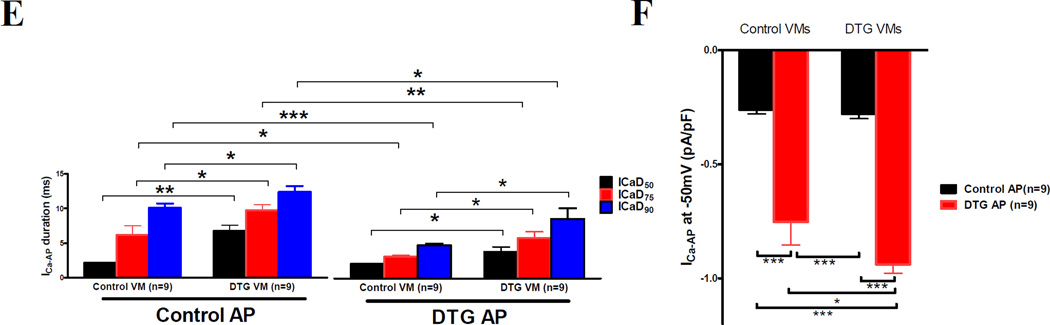

Our data suggest that APD shortening could be an adaptive mechanism for limiting Ca2+ influx into the myocytes to decrease the potential detrimental effects of cellular Ca2+ overload in DTG myocytes. To determine if the shortened APD in DTG myocytes effectively reduced ICa-L to normal levels, ICa-L was measured with the action-potential clamp technique using representative AP shapes from control and DTG myocytes. Total Ca2+ influx with DTG AP clamp was about 17~25% less than with control VM AP clamp in both control and DTG VMs. However, total Ca2+ influx through the Cav1.2 channel was 3.1 times greater in DTG VMs with shortened DTG APs than in control VMs with control APs (Figure 6 A and C). Further examination of the ICa under AP clamp showed that ICa peak was greater with the shortened DTG AP than with the control AP in both DTG and control VMs (Figure 6D). The duration of Ca2+ currents were shortened with DTG type APs in both control and DTG VMs (Figure 6A and E) but the amplitudes of the 2nd peak of ICa under AP clamp were greater than when a normal AP was applied in both control and DTG VMs (Figure 6B and F). These data imply that shortened AP increases peak and tail ICa-L, which could contribute to DTG myocyte Ca2+ overload and depolarization of myocytes during the plateau phase (phase 1) to predispose DTG VMs to EADs and DADs.

Figure 6. Ca2+ currents under AP clamp (ICa-AP) with a typical control AP and a typical DTG AP.

(A) Examples of raw ICa-AP recorded in sodium-free and potassium-free solutions with AP clamp in a control and a DTG VM. (B) Expanded view of tail Ca2+ currents during the repolarizing phase of AP clamp. (C) Total Ca2+ influx through the Cav1.2 channel under AP clamp in control (n=9, N=3) and DTG (n=9, N=3) VMs. (D) The peak of ICa-AP in control and DTG VMs. (E) ICa-AP durations examined at 50%, 75% and 90% decay of ICa-AP. (F) The peak of the tail ICa-AP, usually at about −50mV, the midpoint of AP phase 2 repolarization. There were significant greater tail currents when a shorter AP command was used on both control and DTG VMs. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001; two way ANOVA with repeated measurements and post-hoc t-test was used.

Enhanced Ca2+ influx caused SR Ca2+ overload and increased diastolic Ca2+ sparks frequencies and Ca2+ waves

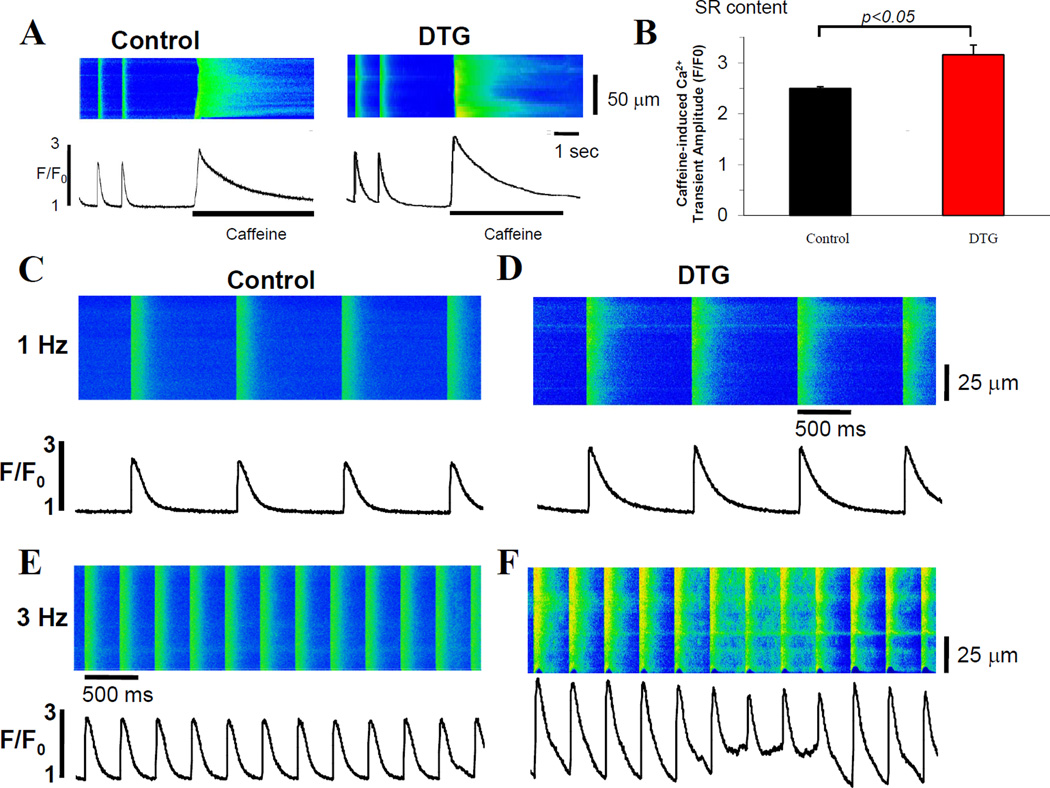

Enhancing Ca2+ influx through the Cav1.2 channel can cause SR Ca2+ overload, which has been considered as a key event for cellular arrhythmogenicity and causes myocyte death [14, 25]. We found that the SR Ca2+ content, indicated by the amplitude of the peak of the caffeine induced Ca2+ transients, was significantly increased in DTG VMs (Figure 7A and B).

Figure 7. β2a DTG VMs have diastolic Ca2+ leaks and Ca2+ waves due to SR Ca2+ overload and increased NCX activity.

(A) Examples of caffeine induced Ca2+ transients following field stimulation induced Ca2+ transients in a control VM and a DTG VM. (B) The amplitudes of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients, an index of SR Ca2+ content. (C) and (D) Examples of line-scanning Ca2+ transients induced by 1Hz field-stimulation in control and DTG VMs. (E) and (F) Examples of line-scanning Ca2+ transients induced by 3Hz field-stimulation in control and DTG VMs. (G) Ca2+ spark frequency at rest in control and DTG VMs. (H) Ca2+ wave frequencies at rest in DTG and control VMs. (I) Abnormal Ca2+ release, i.e., abnormal diastolic Ca2+ and decay as shown in control and DTG myocytes, during field stimulation. (J) and (K) Examples of raw currents recorded during a ramp test (+80mV to −80mV at 100mV/s) before (black line) and after (red line) the application of 5mM NiCl2. The Ni2+-sensitive currents (green line) were considered as INCX. (L) Averaged INCX at −60mV and +60mV showing increased INCX in DTG myocytes. *p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001; unpaired t-test (B, G, H and L) or two way ANOVA with repeated measurements and post-hoc t-test (I) was used.

Ca2+ overloaded SR tends to spontaneously release its stored Ca2+ during diastole which can be measured as spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves. Confocal line scan imaging was used to determine spark frequency within 10 seconds after stopping field stimulation. No differences were observed in the spark properties: amplitude (F/F0), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and full duration at half maximum (FDHM) (Supplemental Figure 2), and Ca2+ spark frequency at rest (Figure 7G) between control and DTG VMs. The Ca2+ wave frequency at rest was significantly increased in DTG VMs (Figure 7H). Under steady state field stimulation, the amplitude of Ca2+ transients was greater at both 1 Hz and 3 Hz frequencies in DTG VMs (Figure 7A and Supplemental Figure 3). The Ca2+ transients of control VMs were quickly decayed and then showed little diastolic Ca2+ release, DTG VMs had a high incidence of abnormal diastolic Ca2+ release at 3Hz (Figure 7C–F and I), which resulted in an elevated diastolic cytosolic Ca2+ concentration at this pacing frequency. Diastolic Ca2+ release causes depolarization of the membrane potential via the electrogenic Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, resulting in EADs and DADs. INCX was significantly increased in DTG VMs (Figure 7 J–L).

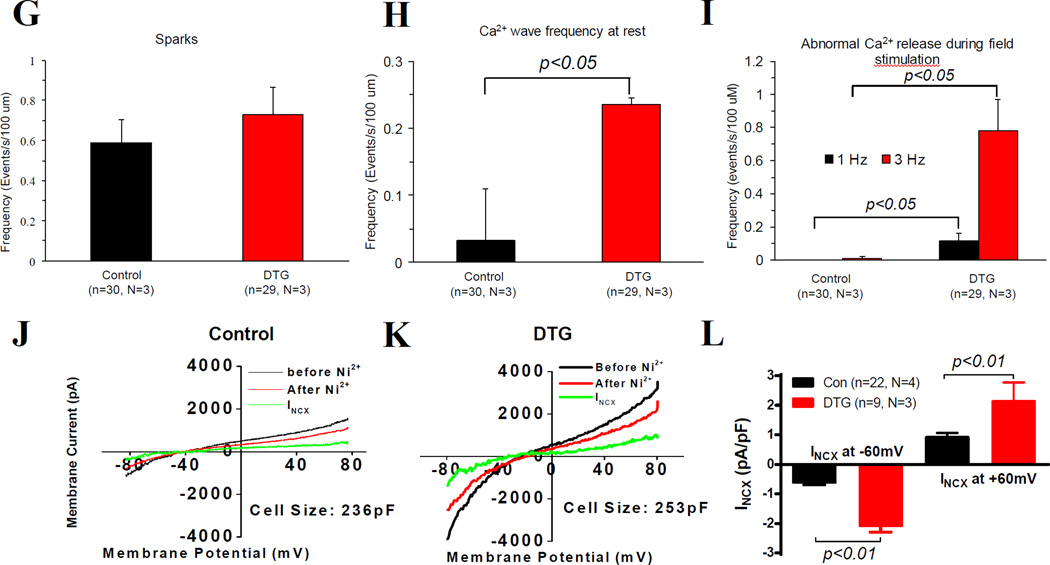

Cavβ2a DTG myocytes had increased EADs and DADs

Diastolic Ca2+ release causes EADs and DADs that underlie arrhythmias [2]. In isolated myocytes, only 3 of the 45 control myocytes had occasional EADs and DADs; in contrast, 8 of 28 DTG VMs had frequent EADs and/or DADs (Figure 8A–D). Among all APs recorded from the 3 control VMs and the 8 DTG VMs with EADs and/or DADs, we found that the percentage of APs with EADs or DADs was significantly higher in DTG (23.6±4.9%) than in control VMs (1.5±0.6%) (Figure 8E). Furthermore, multiple EADs (Figure 8B, arrows) and DADs (Figure 8C, arrows) were often observed together in one AP from DTG myocytes. These results show that EADs and DADs can occur even in DTG myocytes with shortened APs.

Figure 8. A greater proportion of DTG myocytes have early and/or delayed afterdepolarizations (EADs and/or DADs).

Action potentials recorded from one control (A) and two DTG (B & C) VMs, showing EADs and DADs (arrows) in DTG myocytes. (D) A greater proportion of DTG myocytes have EADs and/or DADs than control myocytes. P value was determined by contingency table analysis. (E) The percentage of APs having EADs or DADs in the 3 control VMs with EADs and/or DADs and 8 DTG VMs. VMs were from 5 control and 5 DTG animals.

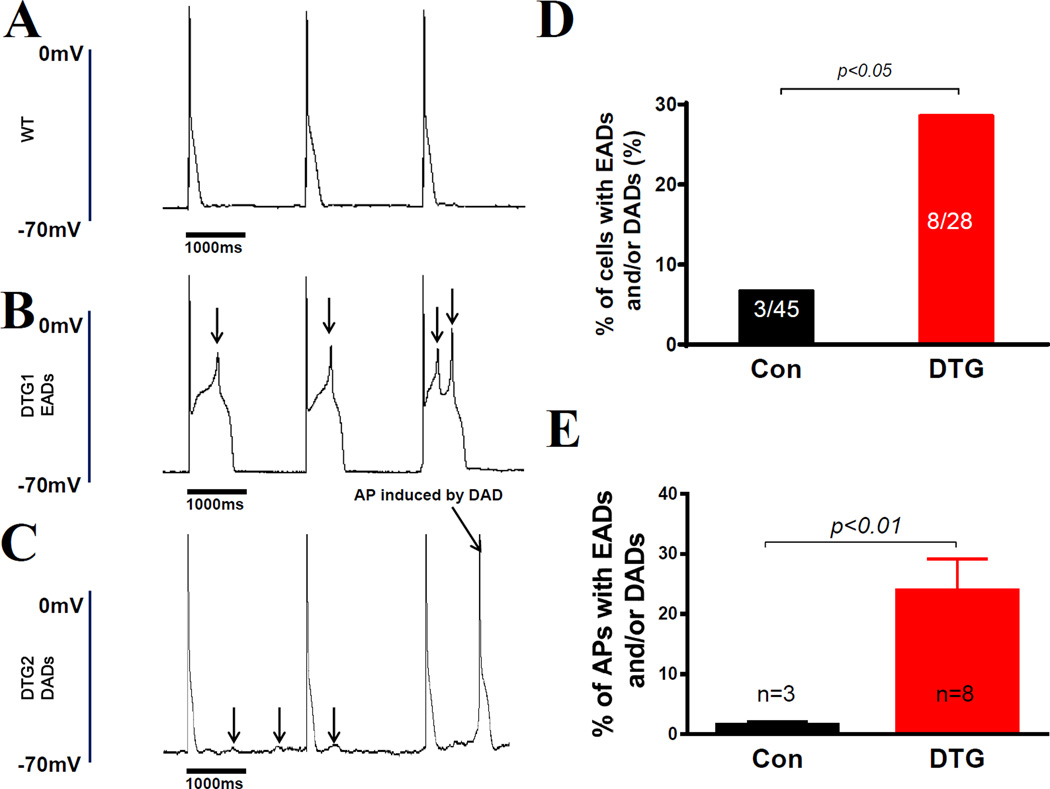

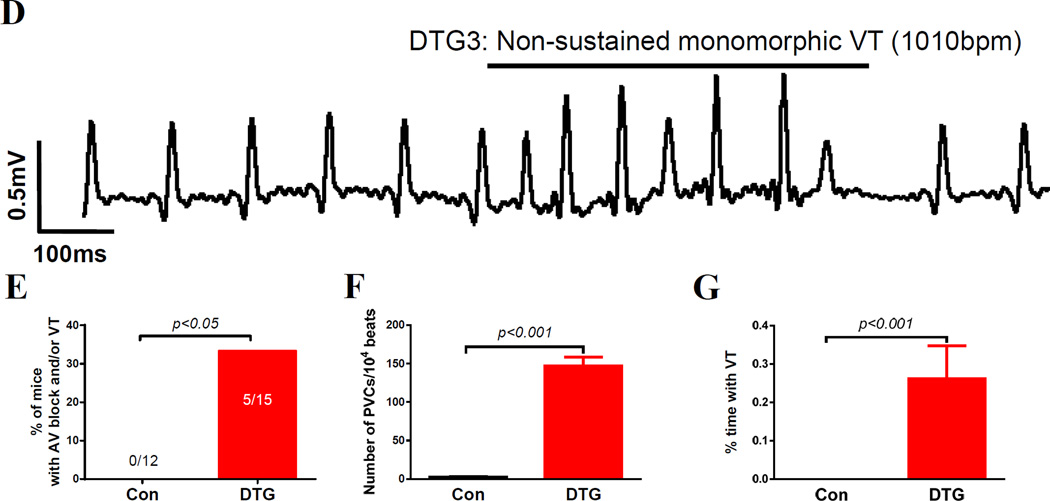

Cavβ2a DTG mice had conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias

To determine if EADs and DADs in DTG myocytes were associated with arrhythmias, we further analyzed telemetric ECG recordings in control and DTG mice. Telemetric ECGs recorded in ambulatory mice showed no difference in heart rates between control and DTG mice but some episodes arrhythmias. AV blocks and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) were found in 5 of 15 DTG mice but in none of control mice (n=12) (Figure 9B–G). Premature ventricular beats (PVC) were found in all 15 DTG mice but only occasionally in one of the 12 control mice (Figure 9B and F). Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) was also observed in 0.27±0.08% of the total recorded time in those 5 DTG animals but not in any examined control mice (Figure 9G). During the recording, one DTG mouse died of bradycardia (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 9. DTG mice have prolonged PR interval, widened QRS duration, and ventricular arrhythmias.

(A) Telemetric ECG from a control mouse. (B). Complete AV block in a DTG mouse. The arrows indicate p waves. (C). Extrasystole/PVC (arrows) recorded from a DTG mouse. (D) Non-sustained VT in a DTG mice. (E) The incidence rate of mice with AV block and/or VT in control (N=12) and DTG (N=15) mice. (F) The numbers of PVCs in every 104 heart beats in control mice (N=12) and DTG mice with PVCs (N=5). (G) The percentage of time with VT in control (N=12) and DTG (N=5) mice. Unpaired student t-test was performed for F and G.

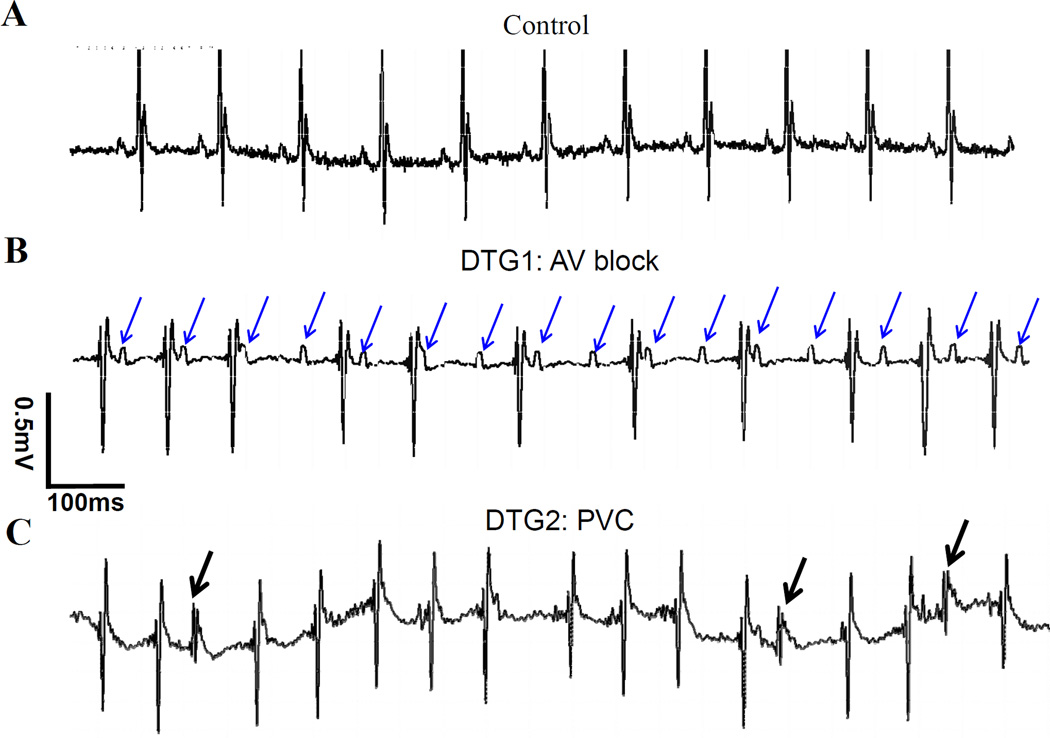

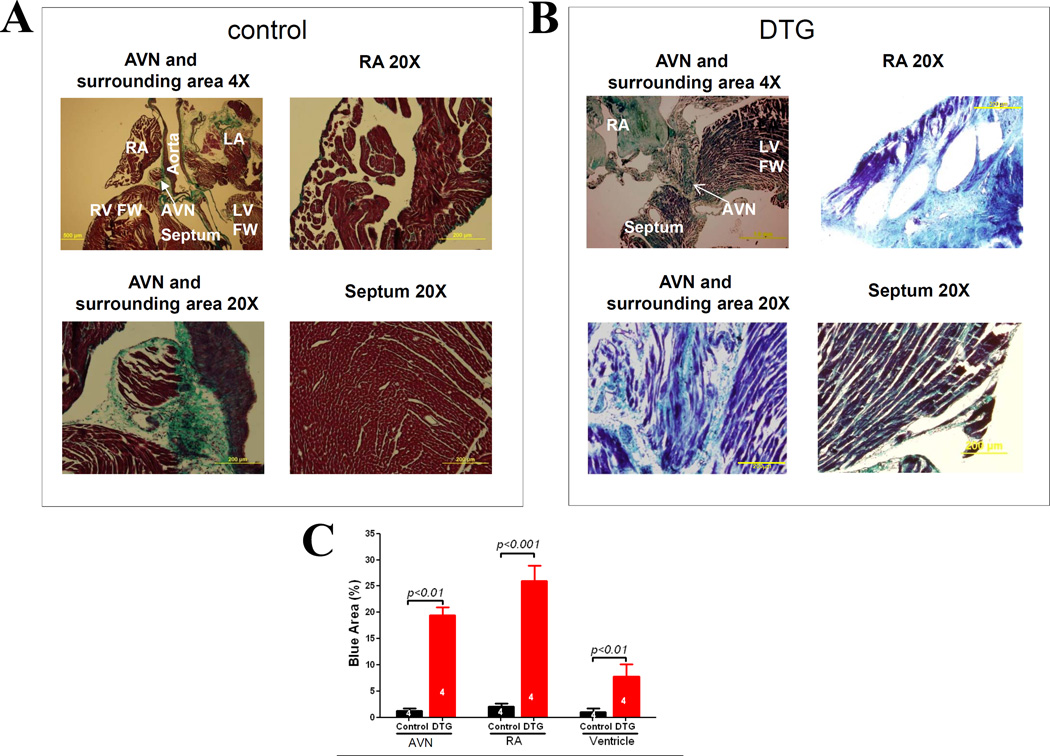

Fibrosis of atrioventricular node (AVN) and myocardium in Cavβ2a DTG mice

We previously reported that there is severe fibrosis of the ventricular walls of Cavβ2a DTG hearts due to myocyte necrosis [25]. AV node fibrosis has been linked to AV blocks [11, 25]. Here we examined if AV node were fibrotic causing AV blocks (Figure 10). In normal control mice, the AV node was surrounded with fibrous tissue that separates the AVN from the ventricles and no fibrosis was seen within the AV node (Figure 10A). In contrast, the AV node of DTG hearts were fibrotic, which could contribute to AV block seen in DTG mice. In addition, Masson’s trichrome staining showed little fibrosis in the atrial walls and ventricular walls of control mice but significant fibrosis in heart walls of the DTG mice (Figure 10).

Figure 10. DTG mice have extensive fibrosis in the atria, AV node (AVN) and ventricles.

(A) & (B) Masson’s trichrome staining of the heart sections of a control mouse (A) and a DTG mouse (B). The blue staining is fibrosis. (C) Quantitation of fibrotic area in the AV node, right atrium (RA) and ventricles. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc t-test (Bonferroni adjustment) was performed for Figure 10C. Four control and 4 DTG hearts were studied. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; FW, free wall; AVN, atrioventricular node.

Discussion

There is an interplay between the alterations of Ca2+ handling and electrical remodeling during the progression of heart disease. It is well known that the action potential profile, especially the phase 1 repolarization shaped by Ito profoundly changes ICa-L, INCX and thus excitation-contraction coupling [31]. Conversely, chronic increases intracellular Ca2+ decreases or increases the expression of transient outward potassium currents depending on the system studied and the time when the animal is studied [28, 30]. Decreases in intracellular Ca2+ enhances the expression of the L-type Ca2+ channel [32]. Increases in Cav1.2 activity may lead to prolongation of the action potential duration and abnormal Ca2+ handling, both contributing to arrhythmogenicity [2, 3, 20]. In this study, we induced a marked and persistent increase in Cav1.2 influx [25] similar to that seen in diseased hearts due to prolongation of action potential [1, 6, 22], chronic activation of the β-adrenergic system [9] and molecular remodeling[12] [21], which may result in cellular Ca2+ overload. We found that these mice had shorter than normal QT intervals and AP durations despite of increased Cav1.2 activity. The shortened QT intervals and APD were caused by significant increases in potassium currents and channel expression. The alteration of action potential duration profoundly affects the time course and Ca2+ influx mediated by ICa-L [1, 6, 22]. However, shortened APD and increasing NCX activity did not effectively limit Ca2+ influx and Cavβ2a overexpression still causes SR Ca2+ overload and spontaneous Ca2+ release, EADs and DADs, and arrhythmias in Cavβ2a DTG mice. SR Ca2+ overload also results in fibrosis of AV node and myocardium to cause conduction abnormalities. These results show that cardiac myocytes are capable of sensing persistent increases in Ca2+ influx through Cav1.2 and remodeling to reduce Ca2+ influx but it may not be adequate in Cavβ2a DTG myocytes.

Does enhanced Cav1.2 activity always prolong QT and myocyte action potentials?

The Cav1.2 channel plays a critical role in triggering Ca2+ release from the SR in cardiac myocytes , and mediates a depolarizing current during the plateau phase (phase 2) of the action potential [7]. The balance between depolarizing currents (mainly ICa) and repolarizing K+ currents determines the duration of the plateaus phase of the AP in large mammals [26]. A prolongation of the AP occurs when Cav1.2 properties change to increase Ca2+ current (e.g., the mutation in Timothy syndrome [4]), and repolarizing potassium currents are not changed. In the Cavβ2a transgenic mice, a reactive increase in repolarizing potassium currents overwhelmed the increases in Cav1.2 activity to shorten the AP durations and QT intervals. Previously, it has been shown that in 4–8 month old transgenic mice overexpressing a Cav1.2α1C , Ito and Iksus in myocytes were increased but APD was not shortened [8]. This discrepancy could be because there is greater increase in ICa-L and probably more electrical remodeling in our animal model. In good agreement, in Cav1.2a1c heterozygous knockout myocytes with reduced ICa-L, the action potential duration was prolonged (Supplemental Figure 6 A & B) when compared to wild type control myocytes. The maximal phase 1 repolarization rate, total Ik, 4-AP insensitive and sensitive Ik were decreased in the heterozygous knockout myocyte (Supplemental Figure 6 C – F). In a transgenic mouse model overexpressing CaMK II peptide inhibitor (Ac3-I) [23], both Cav1.2 activity and Ito expression are increased.

The condition of the heart and the extent of increases in Ca2+ influx also affect the action potential duration. In the mice overexpressing Cav1.2α1c, Ito was increased at the age of 4 months when the heart was in early stage of hypertrophy but decreased at the age of 9–12 months when the heart was in advanced hypertrophic stage [8]. We studied K+ currents in mice overexpressing Cav1.2β2a at high level at the age of 6 months when depressed cardiac function was present [11, 25]. In these myocytes, 4-AP insensitive K+ currents returned to normal but Ito was reduced compared to those in age-matched control and LE DTG myocytes (Supplemental Figure 7).

At last, the way of increasing Ca2+ influx through Cav1.2 may also have effects on action potential duration. The mutation of G406R in Timothy syndrome does not significantly increase the amplitude of ICa-L but it dramatically slows down the inactivation of ICa-L, which causes significant prolongation of the APD [15] and arrhythmias [16]. This is different from our transgenic mouse model in which the ICa-L amplitude is significantly increased but ICa-L inactivation is not significantly different compared to control ICa-L. Whether this difference could result in a different phenotype of our mouse model than the Timothy syndrome model needs to be further studied.

How does increased Ca2+ influx induce increased potassium currents?

Our study shows that persistent increases in Ca2+ influx through the Cav1.2 channel leads to electrical remodeling with an increase in potassium channel abundance and a subsequent decrease in the APD and QT interval. It has been reported that the activation of the calcineurin/NFAT signaling cascade by increased cytosolic Ca2+ is able to upregulate the expression of Kv4.2 channels but not Kv1.4, Kv4.3 and KChIP2 [18]. Calcineurin is activated in the Cavβ2a transgenic mouse [11] and thus this could mediate the upregulation of Kv4.2 we observed. In contrast, it has been reported that increases Ca2+ influx through Cav1.2 in cultured myocytes decreases Ito expression in a calcineurin-dependent manner [28] , and higher calcineurin activity in the endomyocardium may promote lower Kv4.2 channel expression in endomyocardium [30]. In our transgenic mice, the expression of multiple potassium channels (Kv1.4, Kv4.3, Kv2.1, Kir2.2 and KChIP2) are upregulated, thus it is possible different mechanisms are involved. What seems clear is that there is a mechanism that “senses” persistently increased Ca2+ influx through the LTCC and results in an adaptive shortening in APD via increasing the expression of K+ channels, intending to limit excessive Ca2+ entry.

Another possibility is that increased Ca2+ influx [11] activates CaMK II, which then enhances potassium channel activity [27]. Acute overexpression of CaMK IIδ may increase Ik1 density [27], but chronic CaMK II inhibition by an overxpressed peptide (Ac-3I) in a mouse model increases Ito and Ik1 expression [23]. Li et al [23] and others [36] show that decreased SR Ca2+ content could be the central point for the upregulation of potassium channel expression. In our study, the SR content is increased along with potassium channel expression, indicating a complex modulation of potassium channel expression by SR content.

Can AP shortening effectively reduce arrhythmogenic activities in Cavβ2a DTG myocytes and mice?

Prolongation of the QT interval and myocyte action potential is clearly linked to lethal ventricular arrhythmias in humans [20]. Alterations in RyR properties without changing action potential profiles [24] and abnormal SR Ca2+ release are also linked to sudden cardiac death [29]. Our results show that increasing Ca2+ influx through the LTCC causes electrophysiological remodeling that shortens the APD. However, the shortening of the APD does not effectively limits Ca2+ influx into the myocytes and SR Ca2+ overload still occurs. Furthermore, AP shortening may decrease the refractory period and may promote arrhythmias, especially when abnormal Ca2+ release in DTG myocytes causes EADs and DADs. In addition, SR Ca2+ overload may induce myocyte death, myocardial fibrosis [11, 14, 25] and AV node fibrosis, providing the substrates for arrhythmias and conduction blocks. Thus the affected mice showed multiple types of cardiac arrhythmias, AV blocks and die prematurely of sudden death. Collectively our results suggest that SR Ca2+ overload can induce lethal arrhythmias without requiring AP prolongation.

Conclusion

Taking all these results together, our study support the notion that when Ca2+ current is modified, K+ currents change to ensure an appropriate balance between depolarizing and repolarizing currents, which leads to alterations of action potential profile and adjustment to excitation contraction coupling. However, in the face of significant increase of Ca2+ influx, the increases of K+ currents and resultant shortening of action potentials are protective but may not be adequate for preventing SR Ca2+ overload, abnormal SR Ca2+ release, myocyte death and fibrosis, conduction blocks and arrhythmias. It seems that normalization of Ca2+ handling is critical for arrhythmia prevention.

Limitations

Although our data support that arrhythmias are the most likely cause of death of the Cavβ2a DTG mice, we could not rule out the possibility that alterations of cardiac structure of the atria and ventricles cause stroke to kill DTG mice. Additionally, action potential duration varies within different layers of myocardium. In our study, we did not characterize action potentials in myocytes from different layers of myocardium and could not tell the extent of the shortening of APs in different myocardial layers. Nonetheless, shortened QT indicates ventricular myocyte action potentials were shortened on average. At last, there are fundamental differences in cardiac electrophysiology and myocyte Ca2+ handling between humans and mice [27]. Thus, extrapolating our results from our mouse model to humans should be done cautiously.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was supported by NIH and HMMI grants to JDM, NIH HL088243 and AHA 0730347N to XC.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- AP

action potential

- APD

action potential duration

- CaMK II

Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent kinase II

- Cavβ2a

the β2a splicing variant of the β2 subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel

- DAD

delayed after depolarization

- DTG

double transgenic

- EAD

early after depolarization

- ECG

electrocardiography

- ECHO

echocardiography

- FDHM

full duration at half maximum

- FWHM

full width at half maximum

- ICa-L

L-type Ca2+ current

- LTCC or Cav1.2

the L-type Ca2+ channel

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchange

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- PKA

protein kinase A

- QTc

corrected QT interval

- SQTS

short QT syndrome

- RyR2

ryanodine receptor type 2

- SR

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Aiba T, Tomaselli GF. Electrical remodeling in the failing heart. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:29–36. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328333d3d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase and L-type calcium channels; a recipe for arrhythmias? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoons G, Sipido KR. Targeting calcium handling in arrhythmias. Europace. 2008;10:1364–1369. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett CF, Tsien RW. The Timothy syndrome mutation differentially affects voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710501105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry DM, Nerbonne JM. Myocardial potassium channels: electrophysiological and molecular diversity. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:363–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassani RA, Altamirano J, Puglisi JL, Bers DM. Action potential duration determines sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reloading in mammalian ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:593–609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodi I, Muth JN, Hahn HS, Petrashevskaya NN, Rubio M, Koch SE, Varadi G, Schwartz A. Electrical remodeling in hearts from a calcium-dependent mouse model of hypertrophy and failure: complex nature of K+ current changes and action potential duration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1611–1622. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bristow MR, Kantrowitz NE, Ginsburg R, Fowler MB. Beta-adrenergic function in heart muscle disease and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 17 Suppl. 1985;2:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(85)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Piper DR, Sanguinetti MC. Voltage sensing and activation gating of HCN pacemaker channels. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:42–45. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Nakayama H, Zhang X, Ai X, Harris DM, Tang M, Zhang H, Szeto C, Stockbower K, Berretta RM, Eckhart AD, Koch WJ, Molkentin JD, Houser SR. Calcium influx through Cav1.2 is a proximal signal for pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Piacentino V, 3rd, Furukawa S, Goldman B, Margulies KB, Houser SR. L-type Ca2+ channel density and regulation are altered in failing human ventricular myocytes and recover after support with mechanical assist devices. Circ Res. 2002;91:517–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000033988.13062.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Wilson RM, Kubo H, Berretta RM, Harris DM, Zhang X, Jaleel N, MacDonnell SM, Bearzi C, Tillmanns J, Trofimova I, Hosoda T, Mosna F, Cribbs L, Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P, Houser SR. Adolescent feline heart contains a population of small, proliferative ventricular myocytes with immature physiological properties. Circ Res. 2007;100:536–544. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259560.39234.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Zhang X, Kubo H, Harris DM, Mills GD, Moyer J, Berretta R, Potts ST, Marsh JD, Houser SR. Ca2+ influx-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ overload causes mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2005;97:1009–1017. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000189270.72915.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng EP, Yuan C, Navedo MF, Dixon RE, Nieves-Cintron M, Scott JD, Santana LF. Restoration of normal L-type Ca2+ channel function during Timothy syndrome by ablation of an anchoring protein. Circ Res. 2011;109:255–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drum BM, Dixon RE, Yuan C, Cheng EP, Santana LF. Cellular mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias in a mouse model of Timothy syndrome (long QT syndrome 8) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;66:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fozzard HA. Afterdepolarizations and triggered activity. Basic Res Cardiol. 1992;87(Suppl 2):105–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72477-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong N, Bodi I, Zobel C, Schwartz A, Molkentin JD, Backx PH. Calcineurin increases cardiac transient outward K+ currents via transcriptional up-regulation of Kv4.2 channel subunits. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38498–38506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goonasekera SA, Hammer K, Auger-Messier M, Bodi I, Chen X, Zhang H, Reiken S, Elrod JW, Correll RN, York AJ, Sargent MA, Hofmann F, Moosmang S, Marks AR, Houser SR, Bers DM, Molkentin JD. Decreased cardiac L-type Ca(2)(+) channel activity induces hypertrophy and heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:280–290. doi: 10.1172/JCI58227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedley PL, Jorgensen P, Schlamowitz S, Wangari R, Moolman-Smook J, Brink PA, Kanters JK, Corfield VA, Christiansen M. The genetic basis of long QT and short QT syndromes: a mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1486–1511. doi: 10.1002/humu.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hullin R, Khan IF, Wirtz S, Mohacsi P, Varadi G, Schwartz A, Herzig S. Cardiac L-type calcium channel beta-subunits expressed in human heart have differential effects on single channel characteristics. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21623–21630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janczewski AM, Spurgeon HA, Lakatta EG. Action potential prolongation in cardiac myocytes of old rats is an adaptation to sustain youthful intracellular Ca2+ regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:641–648. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Marionneau C, Zhang R, Shah V, Hell JW, Nerbonne JM, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition shortens action potential duration by upregulation of K+ currents. Circ Res. 2006;99:1092–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249369.71709.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu N, Colombi B, Memmi M, Zissimopoulos S, Rizzi N, Negri S, Imbriani M, Napolitano C, Lai FA, Priori SG. Arrhythmogenesis in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: insights from a RyR2 R4496C knock-in mouse model. Circ Res. 2006;99:292–298. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000235869.50747.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakayama H, Chen X, Baines CP, Klevitsky R, Zhang X, Zhang H, Jaleel N, Chua BH, Hewett TE, Robbins J, Houser SR, Molkentin JD. Ca2+- and mitochondrial-dependent cardiomyocyte necrosis as a primary mediator of heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2431–2444. doi: 10.1172/JCI31060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity in the mammalian myocardium. J Physiol 525 Pt. 2000;2:285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nerbonne JM. Studying cardiac arrhythmias in the mouse--a reasonable model for probing mechanisms? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrier E, Perrier R, Richard S, Benitah JP. Ca2+ controls functional expression of the cardiac K+ transient outward current via the calcineurin pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40634–40639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–1167. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossow CF, Dilly KW, Santana LF. Differential calcineurin/NFATc3 activity contributes to the Ito transmural gradient in the mouse heart. Circ Res. 2006;98:1306–1313. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000222028.92993.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, Gidrewicz D, Trivieri MG, Zobel C, Backx PH. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient outward potassium current (I(to)) J Physiol. 2003;546:5–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroder E, Magyar J, Burgess D, Andres D, Satin J. Chronic verapamil treatment remodels ICa,L in mouse ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1906–H1916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00793.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song LS, Sham JS, Stern MD, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Direct measurement of SR release flux by tracking ‘Ca2+ spikes’ in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1998;512(Pt 3):677–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.677bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroud DM, Gaussin V, Burch JB, Yu C, Mishina Y, Schneider MD, Fishman GI, Morley GE. Abnormal conduction and morphology in the atrioventricular node of mice with atrioventricular canal targeted deletion of Alk3/Bmpr1a receptor. Circulation. 2007;116:2535–2543. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang M, Zhang X, Li Y, Guan Y, Ai X, Szeto C, Nakayama H, Zhang H, Ge S, Molkentin JD, Houser SR, Chen X. Enhanced basal contractility but reduced excitation-contraction coupling efficiency and beta-adrenergic reserve of hearts with increased Cav1.2 activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H519–H528. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00265.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, Zhang Z, Timofeyev V, Sharma D, Xu D, Tuteja D, Dong PH, Ahmmed GU, Ji Y, Shull GE, Periasamy M, Chiamvimonvat N. The effects of intracellular Ca2+ on cardiac K+ channel expression and activity: novel insights from genetically altered mice. J Physiol. 2005;562:745–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.