Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the career plans, professional expectations, and well-being of oncology fellows compared with actual experiences of practicing oncologists.

Methods

US oncology fellows taking the 2013 Medical Oncology In-Training Examination (MedOnc ITE) were invited to participate in an optional postexamination survey. The survey evaluated fellows' career plans and professional expectations and measured burnout, quality of life (QOL), fatigue, and satisfaction with work-life balance (WLB) using standardized instruments. Fellows' professional expectations and well-being were compared with actual experiences of US oncologists assessed simultaneously.

Results

Of the 1,637 oncology fellows in the United States, 1,373 (83.9%) took the 2013 MedOnc ITE. Among these, 1,345 (97.9%) completed the postexamination survey. The frequency of burnout among fellows decreased from 43.3% in year 1 to 31.7% in year 2 and 28.1% in year 3 (P < .001). Overall, the rate of burnout among fellows and practicing oncologists was similar (34.1% v 33.7%; P = .86). With respect to other dimensions of well-being, practicing oncologists had lower fatigue (P < .001) and better overall QOL scores (P < .001) than fellows but were less satisfied with WLB (P = .0031) and specialty choice (P < .001). Fellows' expectations regarding future work hours were 5 to 6 hours per week fewer than oncologists' actual reported work hours. Levels of burnout (P = .02) and educational debt (P ≤ .004) were inversely associated with ITE scores. Fellows with greater educational debt were more likely to pursue private practice and less likely to plan an academic career.

Conclusion

Oncology fellows entering practice trade one set of challenges for another. Unrealized expectations regarding work hours may contribute to future professional dissatisfaction, burnout, and challenges with WLB.

INTRODUCTION

The United States is projected to face a profound shortage of oncologists by 2020.1–3 Although oncologists report a high degree of career and specialty satisfaction, recent studies suggest a burnout prevalence of approximately 40%.4,5 A study of US oncologists also suggests satisfaction with work-life balance (WLB) is among the lowest of all medical specialties.6 This dissatisfaction with WLB has profound effects on oncologists' career plans, including reducing the number of hours they devote to patient care.6 This possibility has the potential to exacerbate the projected oncologist shortage.1

One unexplored factor that may contribute to burnout and dissatisfaction with WLB is a mismatch between the expectations oncologists may have when they enter the field and the reality of their professional experiences. It is unknown how accurately oncology fellows' expectations regarding work hours, call schedule, salary, and patient volume match what they will experience when they enter practice. Although fellows typically have extensive experience in academic practice (AP) models, they often have limited exposure to private practice (PP) and other practice settings. Indeed, studies suggest that fellows who prioritize lifestyle considerations are more likely to pursue non-AP settings,7 despite data suggesting that oncologists in PP work more hours per week, see more patients, and have more frequent night call and greater weekend responsibilities.5,6

In addition, although trainees often assume that fatigue, problems with WLB, and professional burnout peak during training (eg, during residency and fellowship), how the experiences of oncology fellows in these domains compare with those of practicing oncologists has not been well studied.8 To explore these aspects, we assessed the career plans and professional expectations of US oncology fellows and measured burnout, quality of life (QOL), fatigue, and satisfaction with WLB using standardized instruments. Fellows' professional expectations and well-being in these dimensions were compared with the actual experiences of practicing oncologists assessed simultaneously.

METHODS

Participants

The Medical Oncology In-Training Examination (MedOnc ITE) was developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) to measure fellows' medical knowledge, establish and demonstrate consistent educational standards for training programs, allow programs to assess program strengths and weaknesses, compare mean scaled test scores among programs, and provide individual fellows with feedback regarding their strengths and weaknesses in specific content areas.9 All US medical oncology fellows completing the 2013 MedOnc ITE (February to March 2014) were invited to participate in an optional 36-item postexamination survey. Participation was voluntary, and all data were deidentified before analysis. ASCO commissioned the study, with human participant oversight provided by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Study Measures

The survey explored personal and professional characteristics using standardized instruments to measure burnout and career satisfaction. Fellows were also asked about their future career plans (including practice setting) as well as their professional expectations once they completed fellowship (hours worked per week, nights on call per week, salary expectations, number of patients they expected to see per week, and average time spent per patient visit [both for new and returning patients]). The full survey is available on request.

Although the 22-item Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the gold standard for measuring symptoms of burnout,10 its length limits feasibility for use in large survey studies exploring multiple content areas, such as the post MedOnc ITE survey. Single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization derived from the full MBI have been shown to be accurate proxy measures of burnout.11–13 These two items strongly correlated with the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization domains of burnout on the full MBI and also demonstrated concordant validity with a host of outcomes related to burnout in a sample of > 10,000 physicians and medical students.11,12 This method has also been used previously in large-scale national studies of > 15,000 US physicians.14 In keeping with previous studies15–17 and convention,18 physicians with high degrees of depersonalization and/or emotional exhaustion were considered to have at least one manifestation of professional burnout.10

Career satisfaction was assessed using two questions from previous physician surveys regarding career and specialty choice16,19–23 and used in recent studies of US oncologists.5 Similar to national studies of physicians and the general US population24 as well as recent studies of US oncologists,5 satisfaction with WLB was assessed by the following item: “My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life” (response options: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree). Individuals who indicated they strongly agreed or agreed were considered to be satisfied with their WLB.

Practicing Oncologist Comparison Group

As previously described,5,6 we surveyed a sample of 2,998 US oncologists between October 2012 and January 2013. Participating oncologists provided detailed information on personal and professional characteristics, including practice setting, hours worked per week, number of patients seen per week, and average time spent per patient visit (both for new and returning patients).

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used to characterize responding oncology fellows. Associations between variables were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test (continuous variables) or χ2 test (categorical variables) as appropriate. All tests were two sided, with type I error rates of 0.05. On the basis of a sample size of 1,345 US oncology fellows, percentage estimates are accurate to within 2.7% with 95% confidence. Multivariable analysis to identify demographic and professional characteristics associated with the dependent outcomes (ITE score and career plans) was performed using logistic regression for dichotomous response variables and mixed linear regression for continuous variables. SAS software (version 9; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Personal and Professional Characteristics

Of the 1,637 US oncology fellows in the academic year 2012 to 2013, 1,373 (83.9%) took the 2013 MedOnc ITE. Among these, 1,345 fellows (97.9%) completed the postexamination survey and are included in our analysis.

The demographic characteristics of participating fellows are listed in Table 1. Median age was 33 years; 47.2% were women, 73.6% were married, and 49.5% had children. Participants were distributed across the traditional 3 years of oncology fellowship training in a relatively even fashion (ie, first year, 29.1%; second year, 36.7%; third year, 33.4%), with a small fraction (0.8%) pursuing a fourth year. Although median educational debt was approximately $25,000, the distribution was somewhat bimodal, with 498 fellows (42.1%) having no educational debt and 379 (32.0%) having > $125,000 in educational debt.

Table 1.

Personal Characteristics and Career Plans of Oncology Fellows

| Characteristic | US Oncology Fellows (n = 1,345) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Age, years | ||

| Missing | 208 | |

| Median | 33.0 | |

| < 30 | 67 | 5.9 |

| 30-34 | 727 | 63.9 |

| 35-40 | 278 | 24.5 |

| > 40 | 65 | 5.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Missing | 152 | |

| Male | 630 | 52.8 |

| Female | 563 | 47.2 |

| Children | ||

| Missing | 162 | |

| Yes | 586 | 49.5 |

| No | 597 | 50.5 |

| Age of youngest child, years | ||

| Missing* | 744 | |

| < 5 | 503 | 83.7 |

| 5-12 | 78 | 13.0 |

| 13-18 | 17 | 2.8 |

| 19-22 | 2 | 0.3 |

| > 22 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Missing | 151 | |

| Single | 252 | 21.1 |

| Married | 879 | 73.6 |

| Partnered | 60 | 5.0 |

| Widow/widower | 3 | 0.3 |

| Ever gone through divorce | ||

| Missing | 156 | |

| Yes | 43 | 3.6 |

| No | 1,136 | 95.5 |

| Currently going through one | 10 | 0.8 |

| Year of training | ||

| Missing | 22 | |

| First | 385 | 29.1 |

| Second | 486 | 36.7 |

| Third | 442 | 33.4 |

| Fourth | 10 | 0.8 |

| Current student loan debt | ||

| Missing | 162 | |

| No debt | 498 | 42.1 |

| < $25,000 | 79 | 6.7 |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 69 | 5.8 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 52 | 4.4 |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 46 | 3.9 |

| $100,000-$125,000 | 60 | 5.1 |

| > $125,000 | 379 | 32.0 |

| Career plans | ||

| Academic practice | ||

| Clinical/translational research | 362 | 28.8 |

| Clinician educator | 231 | 18.4 |

| Basic science (eg, laboratory-based research) | 93 | 7.4 |

| Nonacademic clinical practice | 440 | 35.0 |

| Health care administration† | 3 | 0.2 |

| Nonuniversity research (eg, industry) | 3 | 0.2 |

| State/federal agency (eg, veterans, military) | 118 | 9.4 |

| Undecided | 8 | 0.6 |

| Other | ||

Includes 597 fellows without children.

Without clinical practice.

ITE Scores

Median score of participants on the MedOnc ITE was 524. MedOnc ITE scores increased with year in training, with mean scores of 431, 539, and 595 for first-, second-, and third-year fellows, respectively (P < .001). Demographic characteristics associated with MedOnc ITE score included age (P = .016), relationship status (P < .001), sex (P < .001), and having children (P = .001; Appendix Table A1, online only). An inverse relationship between educational debt was observed for fellows with no debt, $1 to $125,000 in educational debt, and > $125,000 in educational debt, with median ITE scores of 546, 532, and 499, respectively (P < .001).

Burnout and Well-Being Among Fellows Relative to Practicing Oncologists

The frequency of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and burnout among oncology fellows by year in training is listed in Table 2. The prevalence of emotional exhaustion (dimension of burnout) decreased incrementally during the course of fellowship, from 42.7% in year 1 to 29.4% and 25.4% in years 2 and 3, respectively (P < .001). Overall burnout also decreased from 43.3% in year 1 to 31.7% in year 2 and 28.1% in year 3 (P < .001). These improvements in burnout occurred in parallel with improvements in fatigue (P < .001), satisfaction with WLB (P < .001), and overall QOL (P < .001). Although satisfaction with career choice (ie, being a physician) improved from year 1 to 3, satisfaction with specialty choice (oncology) remained stable.

Table 2.

Distress of US Fellows by Year of Training

| Distress | First Year (n = 385) |

Second Year (n = 486) |

Third Year (n = 442) |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Burnout indices* | |||||||

| High emotional exhaustion† | 144 | 42.7 | 130 | 29.4 | 101 | 25.4 | < .001 |

| High depersonalization‡ | 62 | 18.5 | 71 | 16.1 | 54 | 13.6 | .2061 |

| Burnout§ | 146 | 43.3 | 140 | 31.7 | 112 | 28.1 | < .001 |

| QOL | |||||||

| Overall QOL‖ | < .001 | ||||||

| Mean | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.1 | ||||

| SD | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.7 | ||||

| Score < 6 | 101 | 30.2 | 103 | 23.4 | 61 | 15.3 | < .001 |

| Level of fatigue‖ | < .001 | ||||||

| Mean | 5.1 | 5.5 | 5.9 | ||||

| SD | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | ||||

| Score < 6 | 194 | 58.1 | 218 | 49.4 | 161 | 40.6 | < .001 |

| Satisfied with WLB | 115 | 34.6 | 186 | 42.2 | 175 | 44.1 | .0256 |

| Career satisfaction | |||||||

| Would become physician again (career choice) | 263 | 80.2 | 379 | 86.1 | 339 | 86.5 | .0340 |

| Would become oncologist again (specialty choice) | 297 | 90.5 | 389 | 88.8 | 350 | 89.1 | .7176 |

Abbreviations: MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; QOL, quality of life; ROC, receiver operating curve; SD, standard deviation; WLB, work-life balance.

As assessed using single-item measures for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization adapted from full MBI. Area under ROC curve for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization single items relative to that of their respective full MBI domain score in previous studies were 0.94 and 0.93, and positive predictive values of single-item thresholds for high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were 88.2% and 89.6%, respectively.11,12

Individuals indicating symptoms of emotional exhaustion weekly or more often have median emotional exhaustion scores on full MBI of > 30 and have > 75% probability of having high emotional exhaustion score as defined by MBI (≥ 27).

Individuals indicating symptoms of depersonalization weekly or more often have median depersonalization scores on full MBI of > 13 and have > 85% probability of having high depersonalization score as defined by MBI (≥ 10).

High score (≥ weekly) on emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization scale.

On 0- to 10-point Likert scale; higher scores favorable.

The frequency of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and burnout among oncology fellows relative to a national sample of practicing US oncologists studied at approximately the same time point is listed in Table 3. No statistically significant differences were observed between fellows and practicing oncologists with respect to the proportion having high emotional exhaustion (fellows, 32.1% v oncologists, 29.3%; P = .15), high depersonalization (16.1% v 13.4%; P = .07), or high overall burnout (34.1% v 33.7%; P = .86). When compared specifically with third-year fellows, practicing oncologists had higher rates of burnout (33.7% v 28.1%; P = .0411). With respect to other dimensions of well-being and career satisfaction, fellows had higher fatigue (P < .001) and lower overall QOL scores (P < .001) than practicing oncologists but were more satisfied with WLB (40.9% v 34.8%; P = .0031) and specialty choice (89.4% v 80.5%; P < .001).

Table 3.

Burnout, QOL, and Career Satisfaction

| Distress | US Fellows (n = 1,345) |

US Oncologists (n = 1,117) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Burnout indices* | |||||

| High emotional exhaustion† | 385 | 32.1 | 317 | 29.3 | .1459 |

| High depersonalization‡ | 193 | 16.1 | 144 | 13.4 | .0651 |

| Burnout§ | 409 | 34.1 | 367 | 33.7 | .8591 |

| QOL | |||||

| Overall QOL‖ | < .001 | ||||

| Mean | 6.8 | 7.3 | |||

| SD | 1.9 | 1.8 | |||

| Score < 6 | 268 | 22.4 | 161 | 14.6 | < .001 |

| Level of fatigue‖ | .0062 | ||||

| Mean | 5.5 | 5.8 | |||

| SD | 2.2 | 2.4 | |||

| Score < 6 | 583 | 48.8 | 506 | 46.0 | .1691 |

| Satisfied with WLB | 487 | 40.9 | 374 | 34.8 | .0031 |

| Career satisfaction | |||||

| Would become physician again (career choice) | 1,002 | 84.8 | 908 | 82.5 | .1503 |

| Would become oncologist again (specialty choice) | 1,056 | 89.4 | 877 | 80.5 | < .001 |

Abbreviations: MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; WLB, work-life balance.

As assessed using single-item measures for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization adapted from full MBI.

Individuals indicating symptoms of emotional exhaustion weekly or more often.

Individuals indicating symptoms of depersonalization weekly or more often.

High score (≥ weekly) on emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization scale.

On 0- to 10-point Likert scale; higher scores favorable.

Career Plans and Expectations

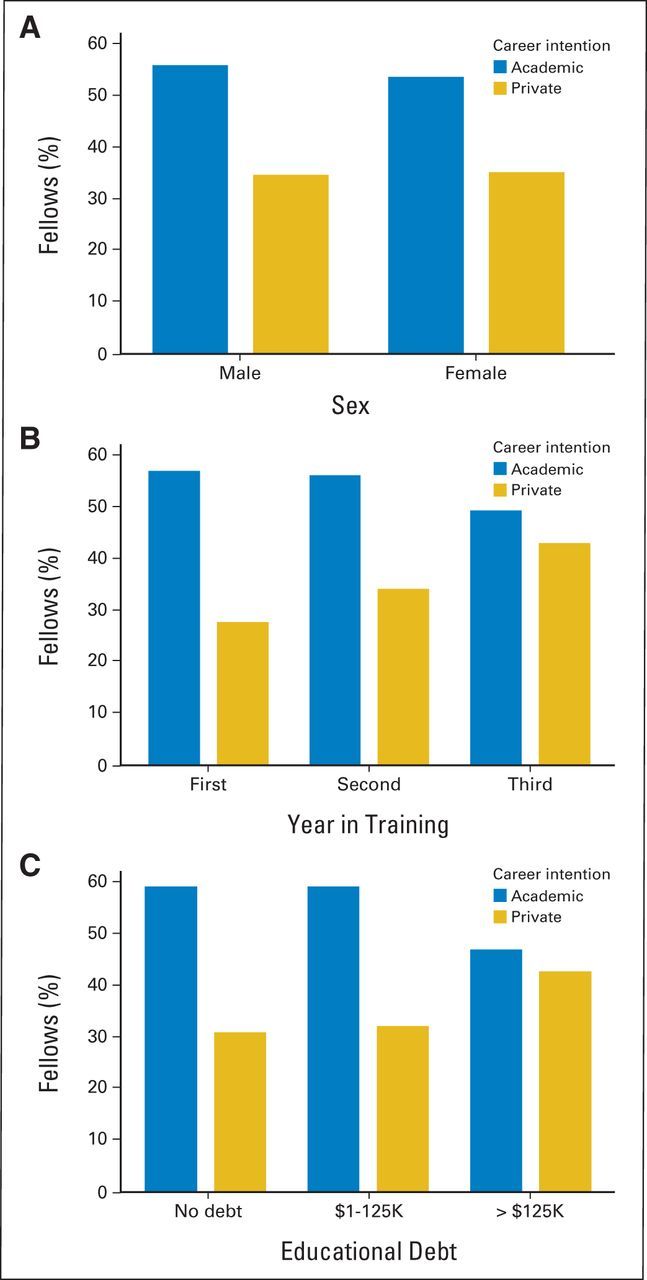

With respect to their anticipated career plans, 686 fellows (51.0%) intended to pursue a career in AP, 440 (35.0%) in PP, and 118 (9.4%) in veterans or military practice. Among the 686 fellows who intended a career in AP, 362 (52.8%) aimed to focus on clinical translational research, 231 (33.7%) on medical education, and 93 (13.6%) on laboratory-based research. Career plans by sex, year in fellowship, and level of educational debt are shown in Figure 1. Intent to pursue AP decreased through the course of training, whereas intent to pursue PP increased (Fig 1B). Fellows with greater educational debt were less likely to select a career in AP and more likely to pursue PP.

Fig 1.

Career plans by (A) sex, (B) year in training, and (C) amount of educational debt.

We next evaluated fellows' expectations regarding the typical work hours, call schedule, patient volume, and average amount of time allocated for each patient once they completed fellowship. Given the differences in these characteristics by practice setting,5 these aspects were evaluated separately based on whether fellows planned to work in PP or AP. The expectations of oncology fellows planning a career in PP relative to the actual experience of practicing oncologists in PP are listed in Table 4. Fellows underestimated the number of hours spent per week on administrative tasks at work, hours spent on work tasks at home each week, and overnight call expectations. They also overestimated the amount of time they would be able to spend on reading to keep abreast of changes in the field. Overall, expectations regarding total hours worked per week for fellows planning a career in PP were 6 hours fewer per week than the actual reported work hours of oncologists in PP (fellows' expectations, 56.9 hours per week; actual work hours, 62.9 hours per week; P = .025). Fellows' expectations regarding the volume of patients seen per week were also substantially lower than that reported by PP oncologists (fellows' expectations, 65.9 patients per week; actual reported, 74.2 patients per week; P < .001). Median salary expectations for fellows planning a career in PP were between $300,000 to $349,999.

Table 4.

Expectations of Oncology Fellows Relative to Reported Work Characteristics of Oncologists

| Future Career Plan | Expectations of Fellows |

Actual Reported Oncologists |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| PP | 440 | 482 | |||

| Call schedule | |||||

| Nights on call per week | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 2.1 | < .001 |

| Work hours | |||||

| Hours seeing patients at work per week | 39.8 | 19.0 | 43.4 | 11.9 | .3349 |

| Hours on administrative tasks at work per week | 7.5 | 5.5 | 8.9 | 6.9 | .0169 |

| Hours at home on work tasks per week† | 5.0 | 4.7 | 7.2 | 7.2 | .0001 |

| Hours at home per week spent keeping abreast of developments in field‡ | 6.3 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 3.3 | < .001 |

| Total work hours per week§ | 56.9 | 25.7 | 62.9 | 16.2 | .0247 |

| Patient care expectations | |||||

| No. of outpatients in clinic per week | 65.9 | 27.3 | 74.2 | 31.0 | < .001 |

| Minutes allocated per new outpatient | 39.8 | 19.0 | 43.4 | 11.9 | .3349 |

| Minutes allocated to returning outpatient | 7.5 | 5.5 | 8.9 | 6.9 | .0169 |

| AP | 686 | 377‖ | |||

| Call schedule | |||||

| Nights on call per week | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | .0731 |

| Work hours | |||||

| Hours seeing patients at work per week | 29.8 | 18.8 | 29.2 | 14.1 | .7396 |

| Hours on administrative tasks at work per week | 9.5 | 7.2 | 14.6 | 11.0 | < .001 |

| Hours at home on work tasks per week† | 8.1 | 6.6 | 10.8 | 8.5 | < .001 |

| Hours at home per week spent keeping abreast of developments in field‡ | 7.0 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 3.8 | < .001 |

| Total work hours per week§ | 53.5 | 26.9 | 58.6 | 17.7 | .0036 |

| Patient care expectations | |||||

| No. of outpatients in clinic per week | 39.1 | 23.6 | 37.4 | 21.0 | .6044 |

| Minutes allocated per new outpatient | 49.7 | 14.3 | 53.9 | 17.0 | < .001 |

| Minutes allocated to returning outpatient | 21.6 | 6.3 | 20.7 | 6.8 | .1509 |

Abbreviations: AP, academic practice; PP, private practice.

Actual reported by oncologists in PP.

Completing paperwork, preparing talks, writing grants/manuscripts, and so on.

Reading journals, maintenance of certification tasks, and so on.

Sum of above four categories.

Actual reported by oncologists in AP.

The expectations of oncology fellows planning a career in AP relative to the actual experience of oncologists in AP are listed in Table 4. Fellows underestimated the number of hours spent per week on administrative tasks at work and hours spent per week on work tasks at home. Fellows overestimated the amount of time they would be able to spend on reading to keep abreast of changes in the field. Overall, expectations regarding total hours worked per week for fellows planning a career in AP were 5 hours fewer per week than the actual reported work hours of oncologists in AP (fellows' expectations, 53.5 hours per week; actual work hours, 58.6 hours per week; P = .004). Expectations regarding the volume of patients seen per week for fellows going into AP were similar to those actually reported by oncologists in AP (fellows' expectations, 39.1 patients per week; actual reported, 37.4 patients per week; P = .6). Median salary expectations for fellows planning a career in AP were between $200,000 to $249,999.

Multivariable Analysis

Finally, we performed multivariable analysis to identify personal and professional characteristics associated with MedOnc ITE score and career plans (Table 5). Factors associated with higher MedOnc ITE scores included increasing year in training, male sex, and having children. Burnout, older age, and greater educational debt were associated with lower MedOnc ITE scores on multivariable analysis.

Table 5.

Multivariable Analysis

| Predictor | Parameter Estimate | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITE score* | |||||

| Second-year fellow (v first year) | 110 | 94 to 126 | < .001 | ||

| Third-year fellow (v first year) | 165 | 149 to 181 | < .001 | ||

| Burned out (v not burned out) | −15 | −29 to −2 | .0256 | ||

| > $125,000 debt (v no debt) | −53 | −68 to −38 | < .001 | ||

| Debt $1-$124,999 (v no debt) | −23 | −39 to −7 | .0050 | ||

| Age (for each year older) | −7 | −8.3 to −4.7 | < .001 | ||

| Male sex (v female) | 39 | 26 to 51 | < .001 | ||

| Children (v no children) | 18 | 5 to 31 | .0076 | ||

| Career plan: PP*† | |||||

| Children (v no children) | 1.74 | 1.33 to 2.28 | < .001 | ||

| > $125,000 debt (v no debt) | 1.65 | 1.22 to 2.24 | .0011 | ||

| Third-year fellow (v first year) | 1.98 | 1.41 to 2.79 | < .001 | ||

| Career plan: AP*† | |||||

| Children (v no children) | 0.62 | 0.48 to 0.80 | < .001 | ||

| > $125,000 debt (v no debt) | 0.60 | 0.45 to 0.79 | < .001 |

NOTE. Three multivariable analyses were conducted to identify personal and professional factors associated with ITE score, planning career in private practice, and planning career in academic practice.

Abbreviations: AP, academic practice; ITE, In-Training Examination; OR, odds ratio; PP, private practice.

Characteristics in model: debt, age, sex, children, fellowship year, burnout, fatigue score; includes first- to third-year fellows.

Additional characteristics in career plan models: ITE score.

With respect to career plans, models were developed to identify characteristics associated with intent to pursue a career in either PP or AP (two most common career plans). Fellows with children and with greater educational debt were more likely to report planning a career in PP, whereas those in the first 2 years of training were less likely to be planning a career in PP. Fellows without children and with lower educational debt were more likely to report planning a career in AP (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Although some of the challenges specific to the practice of medical oncology are recognized, the cause of dissatisfaction with WLB among US oncologists is not well understood. Unrealized expectations for oncologists entering practice may represent a potential contributing factor. In this study, we compared the well-being and career expectations of US oncology fellows with the actual experiences of practicing US oncologists. The results suggest that fellows underestimate future work hours and overestimate the amount of time they will have to keep abreast of developments in the field. Those going into PP also underestimate their future patient care volume. Although fatigue and overall QOL seem to get better after the completion of fellowship, burnout does not improve, and other challenges, such as issues with WLB and career satisfaction, may increase.

Collectively, these findings suggest oncology fellows entering practice will work more hours than they anticipate and trade one set of challenges for another. It is well recognized that physicians work more hours than most US workers13 and that oncologists work more hours than physicians in most other specialties.25 The mismatch between expectations and reality may also be an important source of dissatisfaction among practicing oncologists given the fact that work hours and the amount of time spent providing direct patient care seem to be key drivers of both burnout5 and dissatisfaction6 with WLB among oncologists.

Our results also provide important insights about well-being during the course of fellowship and factors that may influence career plans. Burnout seems to peak in the first year of fellowship and decrease incrementally in the second and third years in parallel with improvements in fatigue, QOL, and WLB. Although a majority of fellows in the first and second years of training plan to pursue an academic career, this commitment decreases in the later years of training. Financial responsibilities related to educational debt and parenting responsibilities seem to have a major influence on fellows' career plans. Fellows with children and those with greater educational debt were more likely to plan a career in PP. Consistent with this notion, median salary expectations of fellows planning a career in PP were approximately $100,000 higher than salaries expected by those planning to pursue AP. This finding is consistent with previous studies of gastroenterology fellows, suggesting those choosing nonacademic careers do so in part because they believe it better meets their financial needs.26 Given the pivotal role academic oncologists play in conducting scientific studies necessary to improve patient outcomes long term, these observations have important implications for efforts (loan repayment programs and so on) to maintain an adequate supply of academic oncologists. Other recent studies have suggested that fellows receiving greater mentorship and who gain experience presenting and publishing research are more likely to choose an AP model.7 Our findings also provide new insights into individual factors that may affect medical knowledge scores on the MedOnc ITE. Specifically, both burnout and increasing educational debt were associated with lower test scores, a finding similar to previous observations in internal medicine residents.14

What can oncology fellowship programs do to reduce distress among oncology fellows and better prepare them for their careers? Several studies have suggested that peer support groups may be a useful strategy to help reduce distress during fellowship.27,28 Other studies suggest that providing oncology fellows training in end-of-life topics and improving the quality of teaching during fellowship may reduce burnout during fellowship.29–31 ASCO has released new curricular guidelines that may help programs improve skill development in these areas.32 Strategies to expose fellows to the care of oncology patients in PP settings may also provide them better insight into the work load, pace, and patient care volumes they may experience once in practice. Fellowship programs have traditionally been frontloaded with respect to clinical duties. Creative approaches to more evenly distribute these responsibilities over the course of training may help reduce burnout during the first year of fellowship but could result in increased burnout in the second and third years. Strategies to reduce burnout and improve career satisfaction that can be applied by fellows individually have also been proposed.8

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. The differences observed between first-, second-, and third-year fellows are based on cross-sectional rather than longitudinal analysis. Given the cross-sectional nature of the study, we are also unable to determine causality or the potential direction of effect for the associations observed. Fellows' intended career plans may change over time, and thus, our analysis of factors that correlate with career plans should be interpreted with caution. Although the participation rate in our sample of practicing oncologists (approximately 50%) is consistent with33 or even higher13,19,34 than physician surveys in general, response bias remains possible. Because international medical graduates often have less educational debt, and educational debt may also influence moonlighting activities,14 it is possible the relationship between debt and burnout in our study is related to interactions between educational debt, moonlighting, and whether an individual is a US or international medical school graduate. We did not collect information on moonlighting activities or whether fellows graduated from a US or international medical school; therefore, we are unable to explore these aspects.

Our study has several potential strengths. The study sample included > 80% of all US oncology fellows across all years of training, and our participation rate of approximately 98% is remarkable. Our study design allowed us to directly evaluate the associations of various personal and professional characteristics with medical knowledge as assessed by the MedOnc ITE. Burnout, fatigue, QOL, and satisfaction with WLB were assessed using standardized tools. Finally, the ability to compare the well-being and expectations of US oncology fellows with the experiences of practicing US oncologists evaluated contemporaneously using the same metrics provides unique insights.

In conclusion, US oncology fellows seem to underestimate the workload they will experience once they enter practice. Oncology fellows entering practice trade one set of challenges for another. Unrealized expectations regarding work hours may contribute to professional dissatisfaction, burnout, and challenges with WLB.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Table A1.

Individual Characteristics and ITE Score

| Characteristic | Mean ITE Score (n = 1,345) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | .0159 | |

| < 30 | 485 | |

| 30-34 | 536 | |

| 35-40 | 519 | |

| > 40 | 517 | |

| Sex | < .001 | |

| Male | 546 | |

| Female | 505 | |

| Children | < .001 | |

| Yes | 541 | |

| No | 513 | |

| Relationship status | < .001 | |

| Single | 498 | |

| Married | 535 | |

| Partnered | 519 | |

| Widow/widower | 579 | |

| Year of training | < .001 | |

| First | 431 | |

| Second | 539 | |

| Third | 595 | |

| Current student loan debt | < .001 | |

| No debt | 546 | |

| $1-$125,000 | 532 | |

| > $125,000 | 499 | |

| Career plans | .0083 | |

| AP | ||

| Clinical/translational research | 537 | |

| Clinician educator | 522 | |

| Basic science (eg, laboratory-based research) | 520 | |

| Nonacademic clinical practice | 534 | |

| Medical/health care administration* | 472 | |

| Nonuniversity research (eg, industry) | 543 | |

| Undecided | 480 | |

| Other | 515 |

Abbreviations: AP, academic practice; ITE, In-Training Examination.

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Drews at www.jco.org/podcasts

Supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, American College of Surgeons Oncology Group, and Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Frances Collichio, Amgen (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: Frances Collichio, Biovex, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, Morphotek Expert Testimony: None Patents, Royalties, and Licenses: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Tait D. Shanafelt, Marilyn Raymond, Leora Horn, Helen Chew, Michael P. Kosty, Jeff Sloan, William J. Gradishar

Financial support: Tait D. Shanafelt, Marilyn Raymond

Administrative support: Marilyn Raymond

Provision of study materials or patients: Marilyn Raymond

Collection and assembly of data: Tait D. Shanafelt, Marilyn Raymond, Daniel Satele, Jeff Sloan, William J. Gradishar

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al. Future supply and demand for oncologists: Challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkwood MK, Kosty MP, Bajorin DF, et al. Tracking the workforce: The American Society of Clinical Oncology workforce information system. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:3–8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkwood MK, Bruinooge SS, Goldstein MA, et al. Enhancing the American Society of Clinical Oncology workforce information system with geographic distribution of oncologists and comparison of data sources for the number of practicing oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:32–38. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L. Oncologist burnout: Causes, consequences, and responses. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1235–1241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:678–686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanafelt TD, Raymond M, Kosty M, et al. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1127–1135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horn L, Koehler E, Gilbert J, et al. Factors associated with the career choices of hematology and medical oncology fellows trained at academic institutions in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3932–3938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt T, Chung H, White H, et al. Shaping your career to maximize personal satisfaction in the practice of oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4020–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collichio FA, Kayoumi KM, Hande KR, et al. Developing an in-training examination for fellows: The experience of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1706–1711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (ed 3) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, et al. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1318–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, et al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1445–1452. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt T, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952–960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004;292:2880–2889. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, et al. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, et al. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. 2006;81:82–85. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Shanafelt TD. Defining burnout as a dichotomous variable. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:440. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0876-6. author reply 441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE, et al. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: Report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3043–3053. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanafelt T, Novotny P, Johnson ME, et al. The well-being and personal wellness promotion practices of medical oncologists in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Oncology. 2005;68:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000084519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank E, McMurray JE, Linzer M, et al. Career satisfaction of US women physicians: Results from the Women Physicians' Health Study—Society of General Internal Medicine Career Satisfaction Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1417–1426. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.13.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemkau J, Rafferty J, Gordon R., Jr Burnout and career-choice regret among family practice physicians in early practice. Fam Pract Res J. 1994;14:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Wipf JE, et al. The effects of work-hour limitations on resident well-being, patient care, and education in an internal medicine residency program. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2601–2606. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, et al. Annual work hours across physician specialties. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1211–1213. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adler DG, Hilden K, Wills JC, et al. What drives US gastroenterology fellows to pursue academic vs. non-academic careers? Results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1220–1223. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekeres MA, Chernoff M, Lynch TJ, Jr, et al. The impact of a physician awareness group and the first year of training on hematology-oncology fellows. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3676–3682. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstrong J, Lederberg M, Holland J. Fellows' forum: A workshop on the stresses of being an oncologist. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19:88–90. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1902_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mougalian SS, Lessen DS, Levine RL, et al. Palliative care training and associations with burnout in oncology fellows. J Support Oncol. 2013;11:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:1263–1269. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baile WF, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP, et al. Improving physician-patient communication in cancer care: Outcome of a workshop for oncologists. J Cancer Educ. 1997;12:166–173. doi: 10.1080/08858199709528481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Hematology-Oncology Curricular Milestones. http://www.asco.org/professional-development/hematology-oncology-curricular-milestones.

- 33.Asch D, Jedrziewski M, Christakis N. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250:463–471. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.