Abstract

Purpose

Most patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are elderly and/or have comorbidities that may make them ineligible for fludarabine-based treatment. For this population, chlorambucil monotherapy is an appropriate therapeutic option; however, response rates with chlorambucil are low, and more effective treatments are needed. This trial was designed to assess how the addition of rituximab to chlorambucil (R-chlorambucil) would affect safety and efficacy in patients with CLL.

Patients and Methods

Patients with first-line CLL were treated with rituximab (375 mg/m2 on day 1, cycle one, and 500 mg/m2 thereafter) plus chlorambucil (10 mg/m2/d all cycles; day 1 through 7) for six 28-day cycles. For patients not achieving complete response (CR), six additional cycles of chlorambucil alone could be administered. The primary end point of the study was safety.

Results

A total of 100 patients were treated with R-chlorambucil, with a median follow-up of 30 months. Median age of patients was 70 years (range, 43 to 86 years), with patients having a median of seven comorbidities. Hematologic toxicities accounted for most grade 3/4 adverse events reported, with neutropenia and lymphopenia both occurring in 41% of patients and leukopenia in 23%. Overall response rates were 84%, with CR achieved in 10% of patients. Median progression-free survival was 23.5 months; median overall survival was not reached.

Conclusion

These results compare favorably with previously published results for chlorambucil monotherapy, suggesting that the addition of rituximab to chlorambucil may improve efficacy with no unexpected adverse events. R-chlorambucil may improve outcome for patients who are ineligible for fludarabine-based treatments.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the commonest adult leukemia in Western countries, affecting almost five in 100,000 in the US population.1 Median age at CLL diagnosis is 72 years,1 with > 40% of patients age > 75 years at diagnosis.1

Current standard treatment for fit patients with CLL is chemotherapy with rituximab (Rituxan; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA; MabThera; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (R-FC).2 The German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) CLL8 study results showed that patients receiving R-FC exhibited significantly higher overall response rates (ORRs) and complete response (CR) rates, leading to improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with patients receiving FC alone. Of patients treated with R-FC, adverse events (AEs) and hematologic toxicities were more frequent in patients age > 65 years compared with younger patients.3 CLL8 eligibility criteria required that patients be fit with limited comorbidities. However, although some elderly patients are fit, most have considerable comorbidities, and because of fludarabine-associated toxicities,4 R-FC is not appropriate for many elderly patients. For example, patients age > 75 years have a mean of 4.2 comorbidities, for all cancer types.5

For patients who are not suited to fludarabine-based treatment, chlorambucil is an appropriate option, as recommended in CLL-treatment guidelines.2,6 However, response rates are modest (31% to 72%), with few patients achieving complete remissions (0% to 7%)7–12; therefore, chlorambucil is frequently used for symptom control only (Appendix Table A1, online only). Also of note is that most of these published chlorambucil studies recruited relatively young patients, eligible for treatment with fludarabine. The GCLLSG CLL5 study results showed no benefit for fludarabine therapy compared with chlorambucil in elderly patients.11 Therefore, more effective treatments are required for elderly, less fit patients. Studies have shown that treatment time and dose affect response rates for single-agent chlorambucil, with higher ORRs reported for 12-month treatment versus 6-month treatment (87.5% v 69.5%)13 and for high-dose chlorambucil versus low-dose chlorambucil (ORR: 420 mg per 28-day cycle, 90% v 70 mg/m2 per 28-day cycle, 72%).13,14 The increased ORR, however, comes at the expense of increased hematologic toxicity and infection rate, which might limit use of such an approach for elderly and less fit patients.

Addition of rituximab to chemotherapy has increased the efficacy of all chemotherapy regimens evaluated in CLL.3,15 Therefore, the combination of rituximab and chlorambucil (R-chlorambucil) is an attractive regimen that could potentially increase activity with good tolerability for patients with CLL who cannot tolerate R-FC. In this phase II study, we evaluated the safety and efficacy of first-line R-chlorambucil in patients with progressive Binet stage B or C CLL. Results are considered in relation to published data for chlorambucil monotherapy in CLL.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

This single-arm, multicenter phase II study (National Cancer Research Institute CLL208) of first-line R-chlorambucil safety and efficacy in patients with CLL was conducted at 12 centers in the United Kingdom. The primary end point was safety of the R-chlorambucil combination; both agents have acceptable AE profiles when used as monotherapy. An increase in grade 3/4 neutropenia incidence or infection risk would be considered an unacceptable toxicity level. Secondary end points were best ORR during treatment and follow-up, confirmed CR, partial response (PR), nodular partial response (nPR), PFS, disease-free survival (DFS), duration of response, OS, and proportion of patients achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (< one CLL cell per 10,000 leukocytes by multiparameter flow cytometry16).

The study was undertaken in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. Approvals for the study protocol (and any modifications thereof) were obtained from independent ethics committees.

Patients

Eligible patients were age ≥ 18 years with previously untreated CD20+ B-cell CLL in progressive Binet stage B or C, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 2 and requiring therapy according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) guidelines. Our study aimed to reflect typical patients diagnosed with CLL in real-world practice; therefore, patients age < 65 years were not excluded from enrollment. Exclusion criteria included previous treatment for CLL, known concomitant hematologic malignancy, transformation to aggressive B-cell malignancy, history of severe cardiac disease, and known hypersensitivity/anaphylactic reactions to murine antibodies.

Treatment

Rituximab was administered on day 1 of six 28-day cycles as an intravenous infusion (375 mg/m2 in cycle one; 500 mg/m2 thereafter) combined with orally administered chlorambucil (10 mg/m2 per day on days 1 to 7 of each cycle). Patients who did not achieve clinical CR but continued to respond after six cycles of chemoimmunotherapy were eligible to receive an additional six cycles of chlorambucil (or until CR was achieved). Follow-up visits were scheduled for all patients until 24 months after their last rituximab infusion.

Assessments

Safety assessments.

AEs were assessed on day 1 of each cycle and at follow-up visits according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3). All AEs were recorded until 28 days after completion of R-chlorambucil (ie, 8 weeks after last administration). All serious AEs (SAEs) were recorded for 6 months post-treatment or until initiation of new CLL treatment if considered unrelated to R-chlorambucil. All SAEs considered to be treatment related were recorded until resolution/stabilization. Laboratory and clinical assessments were also conducted on day 1 of each cycle and at follow-up visits.

Efficacy assessments.

All patients had a computed tomography (CT) scan at baseline (neck [if clinically involved], chest, abdomen, and pelvis) and at confirmation of CR, with additional CT scan evaluation of lymphadenopathies during treatment or follow-up periods if clinically indicated (ie, abnormal initial scan). Response assessment included clinical examination and assessment of B symptoms, evaluation of peripheral blood, and scheduled CT scans. Abnormal (or new) lymph nodes were defined as any ≥ 1.5 cm in diameter. Bone marrow biopsies were performed only for confirmation of CR and were performed after completion of R-chlorambucil rather than as part of the interim response assessment. Response assessments were performed according to NCI revised guidelines for CLL17 after cycle three and cycles six through 12 and at a minimum of 8 weeks and maximum of 12 weeks later for response confirmation.

PFS was defined as the time from start of treatment to earliest date of either progressive disease (PD) or death. DFS was assessed only in patients achieving CR during/within the first 4 months after treatment and was defined as the interval from first response assessment showing CR to earliest date of either PD or death. Duration of response (DoR) was assessed only in patients achieving CR, PR, or nPR and was defined as the time from first assessment showing CR, PR, or nPR to earliest date of either PD or death. OS was defined as the time from treatment start date to date of death.

Statistics

The planned sample size to achieve 100 evaluable patients was 115. The safety population included all patients receiving at least one dose of R-chlorambucil. Because this was a single-arm study, no cross-group comparisons were possible; therefore, sample size was chosen to provide accurate AE detection and response rate assessments. The probabilities of detecting at least one patient with an infrequent or uncommon AE increased with the true event rate (Appendix Table A2, online only). Safety and efficacy data are summarized descriptively, using numbers and percentages of patients in each outcome category. In addition, median times to event with 95% CIs are presented using Kaplan-Meier methods. Although there were no formal stopping criteria defined for safety, a data safety monitoring board monitored all clinically relevant safety events, primarily neutropenia and infections, on an ongoing basis and could recommend stopping the trial if there were concerns over patient safety.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 100 patients were enrolled between November 1, 2007, and October 31, 2009. Of these patients, 49 withdrew before the end of all treatment cycles (including cycles seven through 12) because of AEs/SAEs (n = 25), investigator decision (n = 15), PD (n = 3), protocol deviation (n = 1), and other reasons (n = 5). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 70 years (range, 43 to 86 years); 44% and 56% of patients had Binet stages B and C disease, respectively. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed 13q deletion in 43%, 12q trisomy in 16%, 11q deletion in 13%, and 17p deletion in 3% of patients. More patients had unmutated (52%) than mutated IgVH (36%). Median number of investigator-assessed comorbidities based on medical records at enrollment was seven (range, zero to 20). The percentage of patients with ≥ five comorbidities increased with age; 54.3% of patients age < 70 years had ≥ five comorbidities compared with 81.5% of those age ≥ 70 years.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Prognostic Markers (N = 100)

| Characteristic | Rituximab Plus Chlorambucil |

|---|---|

| Sex, % | |

| Male | 66 |

| Female | 34 |

| Age, years | |

| Median | 70 |

| Range | 43-86 |

| Binet stage, % | |

| B | 44 |

| C | 56 |

| No. of comorbidities | |

| Median | 7 |

| Range | 0-20 |

| IgVH mutation status, % | |

| Mutated | 36 |

| Unmutated | 52 |

| Biclonal or test not performed | 12 |

| Cytogenetics, % | |

| 13q deletion | 43 |

| 12q trisomy | 16 |

| 11q deletion | 13 |

| 17p deletion | 3 |

| No abnormalities or test not performed | 37 |

A total of 69 patients completed all six cycles of R-chlorambucil therapy. Of the patients who responded to therapy without achieving CR, 17 received an additional six cycles of chlorambucil.

Safety

AEs were observed in 99% of patients, the most common being nausea (52%). AEs are listed in Table 2. Neutropenia and lymphopenia were the most frequent grade 3/4 AEs (41%), followed by leukopenia (23%), anemia (19%), and thrombocytopenia (18%). A total of 57 SAEs occurred in 39 patients, with febrile neutropenia being the most frequent (5%), followed by neutropenic sepsis (4%), infusion-related reactions (3%), and back pain, cytokine release syndrome, joint swelling, pneumonia, pyrexia, and vomiting (each 2%). There were 15 deaths; seven resulted from PD, two from secondary malignancies (squamous cell carcinoma and malignant mesothelioma), two from infection, three from CNS events (subdural hematoma, stroke, and cerebral infarction), and one from cardiac arrest.

Table 2.

Adverse Events*

| Event | All Grades (%) | Grade 3/4 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||

| Lymphopenia | 41 | 41 |

| Neutropenia | 41 | 41 |

| Leukopenia | 23 | 23 |

| Anemia | 20 | 19 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 19 | 18 |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Nausea | 52 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 31 | 4 |

| Pyrexia | 29 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 22 | 1 |

| Diarrhea | 20 | 1 |

| Cough | 20 | 1 |

| Chills | 17 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 16 | 1 |

| Constipation | 15 | 0 |

| Headache | 15 | 2 |

| Dizziness | 15 | 4 |

Occurring in ≥ 15 patients.

Of the 58 patients experiencing an infection/infestation, most were of the respiratory tract (upper, 16%; lower, 11%), followed by nasopharyngitis (9%), cellulitis (5%), and urinary tract infection (5%). No opportunistic infections (eg, Pneumocystis pneumonia) were recorded by the investigators, although two patients (2%) experienced pneumonia as an SAE.

Median duration of neutropenic episodes (neutropenic colitis [one episode], neutropenia [69 episodes in 41 patients], febrile neutropenia [seven episodes in six patients], and neutropenic sepsis [five episodes in four patients]) was 10 days (range, 2 to 180 days); > half (58.5%) of neutropenic episodes fully resolved, with an additional 23.2% resolving with sequelae; 17.1% were unresolved, and one case led to death (neutropenic sepsis). Neutropenic episodes led to rituximab dose interruption in 26 patients and chlorambucil dose reduction/interruption in 29 patients. For 11 patients, rituximab and chlorambucil administration was permanently stopped. A single case of grade 3 prolonged neutropenia occurred 56 days after the final cycle of R-chlorambucil, which resolved without treatment. Neutropenic episodes were managed according to institutional practice; 24% of patients received colony-stimulating factor.

Efficacy

The ORR was 84% (95% CI, 75.3% to 90.6%); 10% of patients achieved confirmed CR, and 74% achieved PR; 48 patients had their response confirmed by CT scan. Stable disease/PD was recorded in 15% of patients, whereas 1% were unevaluable; no patients experienced an MRD-negative remission. When grouping patients by prognostic markers, there was a trend for higher ORRs among patients with 12q trisomy (93.8%); IgVH mutation had no impact on ORR (unmutated, 84.6% v mutated, 86.1%), although patients with mutated IgVH seemed to have higher CR (11% v 6%) and nPR rates (14% v 2%) than those with unmutated IgVH (Table 3).

Table 3.

Best Confirmed Response Rates According to Prognostic Markers

| Marker | No. of Patients | CR |

PR |

nPR |

ORR |

PD |

SD |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| IgVH mutation | |||||||||||||

| Mutated | 36 | 4 | 11 | 22 | 61 | 5 | 14 | 31 | 86 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 11 |

| Unmutated | 52 | 3 | 6 | 40 | 77 | 1 | 2 | 44 | 85 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 10 |

| Cytogenetics | |||||||||||||

| 13q deletion | 43 | 4 | 9 | 28 | 65 | 5 | 12 | 37 | 86 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

| 12q trisomy | 16 | 3 | 19 | 10 | 63 | 2 | 13 | 15 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| 11q deletion | 13 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 69 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 77 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 23 |

| 17p deletion | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| Normal | 26 | 4 | 15 | 17 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 81 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 12 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; nPR, nodular partial response; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

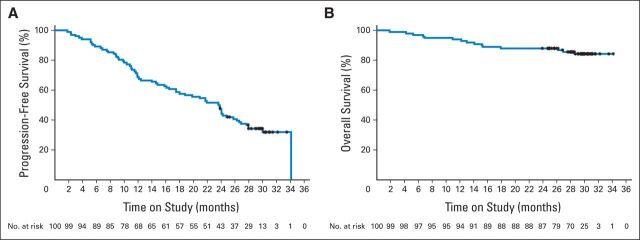

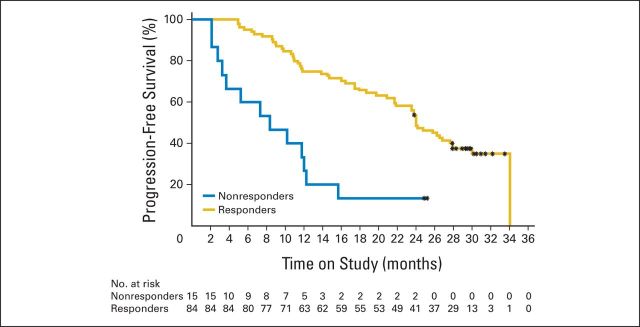

Median DoR was 21.2 months (95% CI, 18.4 to 24.9 months), with a median PFS of 23.5 months (95% CI, 16.4 to 25.8 months; Fig 1A). Patients with 11q deletions had a lower median PFS than those without (359 days; 95% CI, 255 to 717 days v 730 days; 95% CI, 545 to 913 days). Patients with 12q trisomy had a higher median PFS than those without (1,038 days; 95% CI, 545 to 1038 days v 660 days; 95% CI, 441 to 731 days; Appendix Table A3, online only). Other prognostic factors did not seem to greatly affect median PFS. Patients responding to R-chlorambucil had higher median PFS than nonresponders (730 days; 95% CI, 660 to 849 days v 255 days; 95% CI, 85 to 366 days; Appendix Fig A1, online only).

Fig 1.

(A) Progression-free and (B) overall survival in patients treated with rituximab plus chlorambucil. (*) Indicates censored observations.

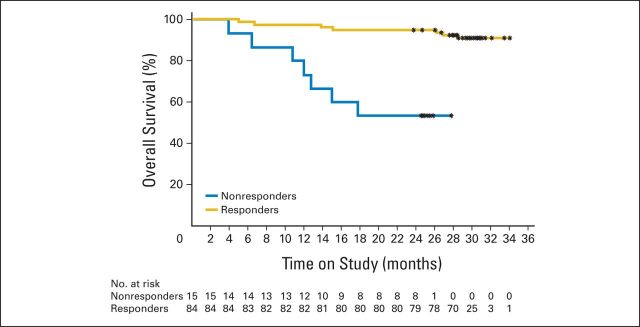

Median OS was not reached, and after 30 months of follow-up, 84 patients were still alive, 15 had died, and one was lost to follow-up (Fig 1B). A higher proportion of responders were alive after 30 months of follow-up compared with nonresponders (90.5% v 53.3%; Appendix Table A4 and Fig A2, online only). Of the patients who did not experience a complete clinical response after six cycles of R-chlorambucil, 17 continued to receive chlorambucil monotherapy; all 17 went on to achieve either CR or PR (Appendix Table A5, online only).

These results compare favorably with published results for chlorambucil monotherapy (median PFS range, 8.3 to 20 months8–12) and in studies with > 6 years of follow-up (OS range, 56 to 64 months9,11; Appendix Table A1, online only). ORRs for chlorambucil monotherapy in previous trials (Appendix Table A1) ranged from 31% to 72%, and CR rates ranged from 0% to 7%. The large variability seen in response and survival rates is likely to be related to differences in age, disease stage, and chlorambucil dose. Most of these trials had a younger patient population eligible for fludarabine treatment.

DISCUSSION

First-line R-chlorambucil safety and efficacy were assessed in this single-arm study of 100 patients with CLL. Patients had a median age of 70 years, closer to the typical age of patients presenting with CLL, and were relatively unfit, exhibiting a median of seven comorbidities, hence requiring a different treatment regimen from the standard of care for fit patients with CLL (ie, R-FC).2,6

The primary end point of the study was safety. Results showed a manageable safety profile for R-chlorambucil. Most AEs were grade 1/2, with nausea being the most common (52%), and most grade 3/4 events were hematologic. In studies of chlorambucil monotherapy,8–12 most AEs were hematologic or nausea/vomiting. Grade 3/4 AEs were most commonly hematologic, with 11% to 40% of patients experiencing grade 3/4 neutropenia (Appendix Table A1, online only). These results are consistent with those of our study and confirm experience from previous trials that rituximab can be safely combined with chemotherapy.3,15 Early in the study, 25 patients discontinued treatment for AEs/SAEs, all of which were neutropenic events. Subsequently, the data safety monitoring board recommended an amendment clarifying dose adaptations of chlorambucil based on previous hematologic toxicities in individual patients, after which no more neutropenia-related discontinuations were reported. Dose adaptations are described in the Appendix material (online only). Most of the neutropenic episodes reported were short lived, and > half of these fully resolved. Although neutropenia incidence may seem high, it is comparable to the 28% incidence seen in the chlorambucil monotherapy arm of the CLL4 trial, which used the same chlorambucil dose to treat a younger patient population (median age, 65 years).8

R-chlorambucil treatment yielded an ORR of 84%, with a 10% CR rate. Responses were seen for all cytogenetic subgroups. Patients with mutated IgVH seemed to have slightly higher CR and nPR rates than those with unmutated IgVH; however, low patient numbers did not allow us to draw a definitive conclusion. After 30 months of follow-up, R-chlorambucil–treated patients exhibited a median PFS of 23.5 months; median OS was not reached.

The GCLLSG CLL5 study is currently the only randomized trial to our knowledge involving patients with CLL who were age > 65 years. The trial randomly assigned patients between chlorambucil and fludarabine monotherapy.10 Patients in the chlorambucil arm had a median age of 70 years, with 40% in Binet stage C and 68% with ≤ one comorbidity. ORR was 51%, with a CR rate of 0%. However, patients in this study received a relatively low chlorambucil dose (0.4 mg/kg on day 1, with stepped 0.1 mg/kg dose increases per cycle up to a maximum of 0.8 mg/kg over course of six cycles [mean dose, 38 mg/m2 per 28-day cycle]). The most surprising finding of the study was that with a longer follow-up, the OS data favored chlorambucil treatment over fludarabine, despite the fact that the responses were superior for fludarabine-treated patients. A possible explanation is that because the patients were older than those in previous studies, they were unable to tolerate postfludarabine salvage therapy, whereas those randomly assigned to chlorambucil could receive therapy at relapse. The authors concluded that chlorambucil was the still the best treatment available for elderly patients. Comparing the results of our trial with this trial, it seems that the addition of rituximab could provide additional benefits to chlorambucil monotherapy.

Dosages per cycle in previous studies ranged from 38 to 70 mg/m2. The Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research CLL4 trial assessed safety and efficacy of patients with CLL treated with either chlorambucil, fludarabine, or FC.8 In this study, patients in the chlorambucil arm received 70 mg/m2 of chlorambucil per cycle, achieving an ORR of 72% (CR, 7%). In contrast to the GCLLSG CLL5 study, patients in this trial had a median age of 65 years, were relatively fit, and were therefore eligible for fludarabine treatment. Again, despite the variability introduced by differences in patient characteristics and dosages, R-chlorambucil response rates of fludarabine-ineligible patients with CLL compared favorably with the results from these studies. Patients enrolled onto this study were Binet stage B/C and exhibited a number of comorbidities. In contrast, most previous studies enrolled patients who were fitter and hence eligible for treatment with fludarabine, which was frequently used as a comparator arm in these studies.

Our study results suggest that first-line chlorambucil combined with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody is an effective option. Two next-generation antibodies under investigation are obinutuzumab (GA101), a glycoengineered type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, and ofatumumab, both currently under investigation in the first-line CLL setting combined with chlorambucil. The positive data from our study contributed to the design of the randomized phase III GCLLSG CLL11 trial to assess GA101 combined with chlorambucil in patients considered unfit for fludarabine (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale > 6 and/or creatinine clearance < 70 mL/min).18 First-line chlorambucil combined with ofatumumab is also being assessed in the COMPLEMENT-1 trial (Clinical Trial of Ofatumumab in Patients With CLL As Initial Treatment).19 It would also be worthwhile to explore the combination of anti-CD20 antibodies with other chemotherapies such as bendamustine, which has been shown to be superior to chlorambucil in a younger patient population (median age, 66 years) without any defined comorbidities.20 Therefore, the combination of rituximab with chlorambucil is well tolerated and effective and can form the basis for future therapies in patients considered unfit for fludarabine-based therapy.

Acknowledgment

We thank Colin Hayward (formerly of F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), Dimitri Messeri, and Stuart Osborne (F. Hoffmann-La Roche) for their contribution to writing the protocol, conducting the study, and writing the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the data safety monitoring board members.

Appendix

Table A1.

Reported Response Rates and Adverse Events in Chlorambucil Monotherapy Arms of Various Studies

| Study Treatment | No. of Patients | Median Age (years) | Binet Stage C (%) | Rai Stage III/IV (%) | Dose per Cycle (mg/m2)* | Efficacy |

Safety (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutropenia |

Infections (all grades) | Nausea (all grades) | |||||||||||

| ORR (%) | CR (%) | PFS (months) | OS (months) | All Grades | Grade 3/4 | ||||||||

| Fludarabine v chlorambucil v fludarabine plus chlorambucil8 | 193 | 64 | — | 41 | 40 | 37 | 4 | 14.0 | 56 | NR | 19 | NR | NR |

| Chlorambucil v fludarabine v fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide7 | 387 | 65 | 31 | — | 70 | 72 | 7 | 20.0 | Not reached | 28 | NR | NR | NR |

| Alemtuzumab v chlorambucil9 | 148 | 59 | — | 34 | 40 | 55 | 2 | 11.7 | Not reached | NR | 25 | NR | 35 |

| Chlorambucil v fludarabine10 | 100 | 70 | 40 | 43 | 38 | 51 | 0 | 18.0 | 64 | NR | 40 | 32 | NR |

| Bendamustine v chlorambucil11 | 157 | 64 | 29 | — | 60 | 31 | 2 | 8.3 | Not reached | 14 | 11 | 1 | 14 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; NR, not reported; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Based on average patient of 70 kg or 1.85 m2.

Table A2.

Probability of Event Detection for Given True Event Rate

| Variable | Rate/Probability (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True event rate | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 |

| Probability of detection | 10 | 39 | 63 | 87 | 99 | > 99 |

Table A3.

PFS by Prognostic Factors and Cytogenetic Subgroups

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | PFS (days) |

Patient Status After 30-Month Follow-Up |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Event |

PD |

Dead |

Lost to Follow-Up |

||||||||

| Median | 95% CI | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Binet stage | |||||||||||

| B | 44 | 650 | 359 to 849 | 14 | 31.8 | 28 | 63.6 | 2 | 4.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| C | 56 | 720 | 477 to 817 | 17 | 30.4 | 33 | 58.9 | 5 | 8.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Age, years | |||||||||||

| < 65 | 28 | 659 | 374 to NE | 10 | 35.7 | 18 | 64.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ≤ 65 | 72 | 720 | 477 to 798 | 21 | 29.2 | 43 | 59.7 | 7 | 9.7 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Responders | |||||||||||

| CR/PR | 84 | 730 | 660 to 849 | 29 | 34.5 | 49 | 58.3 | 5 | 6.0 | 1 | 1.2 |

| Nonresponders | 15 | 255 | 85 to 366 | 2 | 13.3 | 12 | 80.0 | 1 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IgVH status | |||||||||||

| Mutated | 36 | 738.5 | 374 to 1,038 | 14 | 38.9 | 18 | 50.0 | 3 | 8.3 | 1 | 2.8 |

| Normal | 52 | 690.5 | 359 to 730 | 11 | 21.2 | 40 | 76.9 | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 17p deletion status | |||||||||||

| Deleted | 0 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |||||

| Normal | 86 | 727 | 545 to 817 | 29 | 33.7 | 53 | 61.6 | 3 | 3.5 | 1 | 1.2 |

| 11q deletion status | |||||||||||

| Deleted | 13 | 359 | 255 to 717 | 1 | 7.7 | 12 | 92.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 76 | 730 | 545 to 913 | 28 | 36.8 | 44 | 57.9 | 3 | 3.9 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 12q trisomy status | |||||||||||

| +12q | 16 | 1,038 | 545 to 1,038 | 9 | 56.3 | 6 | 37.5 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 73 | 660 | 441 to 731 | 20 | 27.4 | 50 | 68.5 | 2 | 2.7 | 1 | 1.4 |

| 13q deletion status | |||||||||||

| Deleted | 43 | 716 | 374 to 849 | 13 | 30.2 | 28 | 65.1 | 2 | 4.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 46 | 727 | 477 to 808 | 16 | 34.8 | 28 | 60.9 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.2 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; NE, not evaluated; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response.

Table A4.

OS by Prognostic Factors and Cytogenetic Subgroups

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | OS (days) | Patient Status After 30-Month Follow-Up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive |

Dead |

Lost to Follow-Up |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Binet stage | ||||||||

| B | 44 | NR | 40 | 90.0 | 4 | 9.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| C | 56 | NR | 44 | 78.6 | 11 | 19.6 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| < 65 | 28 | NR | 25 | 89.3 | 3 | 10.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ≥ 65 | 72 | NR | 59 | 81.9 | 12 | 16.7 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Responders | ||||||||

| CR/PR | 84 | NR | 76 | 90.5 | 7 | 8.3 | 1 | 1.2 |

| Nonresponders | 15 | NR | 8 | 53.3 | 7 | 46.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IgVH status | ||||||||

| Mutated | 36 | NR | 28 | 77.8 | 7 | 19.4 | 1 | 2.8 |

| Normal | 52 | NR | 48 | 92.3 | 4 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 17p deletion status | ||||||||

| Deleted | 0 | NE | NE | NE | NE | |||

| Normal | 86 | NR | 74 | 86.0 | 11 | 12.8 | 1 | 1.2 |

| 11q deletion status | ||||||||

| Deleted | 13 | NR | 10 | 76.9 | 3 | 23.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 76 | NR | 67 | 88.2 | 8 | 10.5 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 12q trisomy status | ||||||||

| +12q | 16 | NR | 15 | 93.8 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 73 | NR | 62 | 84.9 | 10 | 13.7 | 1 | 1.4 |

| 13q deletion status | ||||||||

| Deleted | 43 | NR | 38 | 88.4 | 5 | 11.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 46 | NR | 39 | 84.8 | 6 | 13.0 | 1 | 2.2 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; NE, not evaluated; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response.

Table A5.

Tumor Response: Cycles Seven to 12

| Cycle/Visit | No. of Patients | CR |

PR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| 7 | 17 | 3 | 17.6 | 14 | 82.4 |

| 8 | 13 | 2 | 15.4 | 11 | 84.6 |

| 9 | 11 | 3 | 27.3 | 8 | 72.7 |

| 10 | 9 | 3 | 33.3 | 6 | 66.7 |

| 11 | 8 | 3 | 37.5 | 5 | 62.5 |

| 12 | 7 | 4 | 57.1 | 3 | 42.9 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; PR, partial response.

Fig A1.

Progression-free survival analysis: nonresponders versus responders. (*) Indicates censored observations.

Fig A2.

Overall survival analysis: nonresponders versus responders. (*) Indicates censored observations.

Footnotes

Written on behalf of the National Cancer Research Institute Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Subgroup.

Supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, which also provided third-party writing assistance.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information: NCT00532129.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Stephan Oertel, F. Hoffmann-La Roche (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: Peter Hillmen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche (C); George A. Follows, Roche (C); Claire E. Dearden, Roche (C), Genzyme (C), Celgene (C); Daniel B. Kennedy, Roche (C); Andrew R. Pettitt, Roche (C), GlaxoSmithKline (C); Andy Rawstron, Gilead (C), Biogen Idec (C) Stock Ownership: Stephan Oertel, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Honoraria: Peter Hillmen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche; John G. Gribben, Roche/Genentech, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, GlaxoSmithKline; George A. Follows, Roche; Donald Milligan, Roche; Claire E. Dearden, Roche, Celgene; Daniel B. Kennedy, Roche; Andrew R. Pettitt, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline; Andy Rawstron, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Genzyme; Christopher F.E. Pocock, Roche Research Funding: Peter Hillmen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche; George A. Follows, Roche; Andrew R. Pettitt, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline; Dena Cohen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Expert Testimony: Andrew R. Pettitt, Roche (U), GlaxoSmithKline (U) Patents, Royalties, and Licenses: None Other Remuneration: Andy Rawstron, Roche/Genentech

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Peter Hillmen, George A. Follows, Donald Milligan, Andrew R. Pettitt

Provision of study materials or patients: Peter Hillmen, George A. Follows, Donald Milligan, Amit Nathwani

Collection and assembly of data: John G. Gribben, George A. Follows, Donald Milligan, Hazem A. Sayala, Paul Moreton, David G. Oscier, Claire E. Dearden, Daniel B. Kennedy, Andrew R. Pettitt, Abraham Varghese, Andy Rawstron, Stephan Oertel, Christopher F.E. Pocock

Data analysis and interpretation: Peter Hillmen, Amit Nathwani, Dena Cohen, Andy Rawstron, Stephan Oertel

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2009 (vintage 2009 populations): 2011 update—National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/

- 2.Zelenetz AD, Abramson JS, Advani RH, et al. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas—Version 1. 2013. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf.

- 3.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shvidel L, Shtalrid M, Bairey O, et al. Conventional dose fludarabine-based regimens are effective but have excessive toxicity in elderly patients with refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:1947–1950. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000110991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancik R. Cancer burden in the aged: An epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer. 1997;80:1273–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichhorst B, Dreyling M, Robak T, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(suppl 6):vi50–vi54. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catovsky D, Fooks J, Richards S. The UK Medical Research Council CLL trials 1 and 2. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1988;30:423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, et al. Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, et al. Fludarabine compared with chlorambucil as primary therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1750–1757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillmen P, Skotnicki AB, Robak T, et al. Alemtuzumab compared with chlorambucil as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5616–5623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:3382–3391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Phase III randomized study of bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4378–4384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catovsky D, Hamblin T, Richards SJ. Preliminary results of the UK MRC trial in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: CLL3. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:278. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaksic B, Brugiatelli M, Krc I, et al. High dose chlorambucil versus Binet's modified cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone regimen in the treatment of patients with advanced B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of an international multicenter randomized trial—International Society for Chemo-Immunotherapy, Vienna. Cancer. 1997;79:2107–2114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robak T, Dmoszynska A, Solal-Céligny P, et al. Rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide prolongs progression-free survival compared with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1756–1765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rawstron AC, Villamor N, Ritgen M, et al. International standardized approach for flow cytometric residual disease monitoring in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:956–964. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored working group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goede V, Fischer K, Humphrey K, et al. Obinutuzumab (GA101) plus chlorambucil (Clb) or rituximab (R) plus Clb versus Clb alone in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and pre-existing medical conditions (comorbidities): Final stage 1 results of the CLL11 (BO21004) phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;(suppl 15):31. abstract 7004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ofatumumab + chlorambucil vs chlorambucil monotherapy in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (COMPLEMENT 1) http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00748189.

- 20.Knauf WU, Lissitchkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Updated results of a randomized phase III trial. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:67–77. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]