Abstract

Introduction

Using National HIV surveillance system data we estimated life expectancy and average years of life lost among person diagnosed with HIV infection during 2008–2011.

Methods

Population-based surveillance data, restricted to persons with diagnosed HIV infection age 13 years or older, from all 50 states and D.C. were used to estimate life expectancy after HIV diagnosis using the life table method. Generated estimates were compared with life expectancy in the general population in the same calendar year to calculate average years of life lost (AYLL). Life expectancy and average years of life lost were also estimated for subgroups by age, sex and race/ethnicity.

Results

The overall life expectancy after HIV diagnosis in the United States, increased 3.43 years from 25.43 (95% Confidence interval (CI) 25.37–25.49) in 2008, to 28.86 (95% CI 28.80–28.92) in 2011.

Improvements were observed irrespective of sex, race/ethnicity, transmission category and stage of disease at diagnosis, though the extent of improvement varied by different characteristics. Based on the life expectancy in the general population, in 2010 the AYLL, were 12.8 years for males and 16.5 years for females. By race/ethnicity, on average blacks (13.3 years) and whites (13.4 years) had fewer AYLL than Hispanic/Latinos (14.7).

Conclusions

Despite improvements in life expectancy among people diagnosed with an HIV infection during 2008–2011, disparities by sex and by race/ethnicity persist. Targeted efforts should continue to further reduce disparities and improve life expectancy after HIV diagnosis.

Keywords: Life expectancy, HIV, population-based

Introduction

Introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid-1990s brought significant improvement in survival of people living with diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (PLWDH). Previous estimates of survival or life expectancy after HIV diagnosis showed an increase from 10.5 years in 1996 to 22.5 years, in 20051 among people who were diagnosed with an HIV infection during that period. As treatments have evolved further, it is plausible that life expectancy after an HIV diagnosis has improved since the last estimates. Survival and life expectancy are also important measures to determine disparities in HIV care and treatment outcomes, and contribute to monitoring national objectives to reduce disparities and HIV-related mortality set by National HIV/AIDS Strategy and the Healthy people 20202,3. Another quantitative measure of changes in life expectancy is the average years of life lost (AYLL), after a change in health status, such as diagnosis of a disease. The AYLL (also called potential years of life lost) is an estimate of the number of years of life ‘lost’ because of premature mortality occurring in a person with a certain health condition. At the population level, in HIV’s context, AYLL represent the average number of additional years a person living with diagnosed HIV would have lived if that person had not died prematurely4. The knowledge of AYLL can be useful in drafting legislation and resource allocation, and serve as a measure of an individual’s disease burden for improving planning for clinical care5.

While some estimates of mortality and life expectancy are available6-11, the studies were either done outside of the United States or on a subset of PLWDH, such as those receiving care at a particular health care facility, and therefore did not represent large population-based estimates of life expectancy. The only large surveillance-data based estimates of life expectancy available from the United States 1 covered PLWDH, with HIV diagnosed by year 2005 and included data from only 25 states. With advancements in treatment and the potential impact on life expectancy following HIV diagnosis, these estimates need to be updated with new and more recent data representing the entire country.

We used National HIV Surveillance System (NHSS) data from all 50 states and Washington D.C. to estimate the life expectancy among people who were diagnosed with an HIV infection during 2008– 2011. We also estimated AYLL in the year 2010 by comparing the life expectancy estimates generated by our analysis with the life expectancy of the general U.S. population for that year.

Methods

As part of NHSS, all states and the District of Columbia have reported cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since the early 1980s. Starting in 1994, jurisdictions that adopted confidential name-based HIV surveillance started reported cases of HIV infection to CDC. By April of 2008, all 50 states and District of Columbia had implemented confidential name-based HIV surveillance. In this analysis, NHSS data from entire country were used to estimate the life expectancy after HIV diagnosis among adults and adolescents (≥ 13 years of age) during 2008–2011. All data reported to the CDC through June 2013 were used. This allowed for a minimum period of 18 month for reporting of deaths occurring by the end of 2011. All deaths, irrespective of cause, among people with diagnosed HIV infection were included in this analysis and data were adjusted for reporting delays and missing risk factors 12,13.

Following National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) approach, we modeled life expectancy after HIV diagnosis, using the period life table method 14 that is based on the mortality experience of a hypothetical cohort and assumes that the age-specific death rates remain unchanged in future years. This means that persons who will be in a given age bracket in the future will experience the same age-specific death rates as the one experienced by persons currently in that age bracket. We used an exponential model for estimating age-specific death rates, in which the death rates within one year after diagnosis of HIV and deaths rates more than one year after diagnosis were estimated separately, because the death rates in the two time periods are quite different 15.

We estimated overall life expectancy in each of the four years of diagnosis (2008–2011) as well as by selected characteristics of interest that included sex at birth, race/ethnicity, HIV stage at diagnosis and HIV transmission category. Race/ethnicity was categorized into four categories; black/African American (hereafter referred to as black), Hispanic/Latino, white and ‘other races’ representing a cumulative category for all minority races/ethnicities other than blacks and Hispanics/Latinos. HIV stage at diagnosis was categorized into two categories; stage 3 [AIDS] vs. other that included persons whose stage at diagnosis was unknown. We also estimated life expectancy separately for males and females by the four HIV transmission categories among males [male-to-male sexual contact, injection-drug use (IDU), male-to-male sexual contact and IDU, and heterosexual contact), and by two transmission categories among females (IDU and heterosexual contact].

We estimated AYLL by sex and by the age at HIV diagnosis, by subtracting the estimated life expectancy of the person with an HIV diagnosis from the life expectancy of an individual of the same age and sex, in the general population in 2010, using NCHS vital statistics data for 2010 14.

Results

In the four years from 2008 to 2011, an estimated total of 184,749 persons were diagnosed with HIV in the United States. The total number of diagnoses each year decreased from 2008 through 2011. This decrease was also observed across both sexes, most races/ethnicities, and by stage of disease at diagnosis. However, the distribution of diagnoses by sex, race/ethnicity and stage at diagnosis remained similar across the years. By transmission category, a similar decline was observed except among males with infection attributed to male-to-male sexual contact [hereafter referred to as men who have sex with men (MSM)], which showed a slight increase (<2%) in numbers from 2008 to 2011 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated numbers of diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents, by selected characteristics, 2008–2011, United States.

| Year of diagnosis | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of diagnoses1 | 49,061 | 46,403 | 44,931 | 44,354 |

|

| ||||

| Sex | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| ||||

| Male | 37,154 (75.7) | 35,794 (77.1) | 35,045 (78.0) | 35,011 (78.9) |

| Female | 11,908 (24.3) | 10,610 (22.9) | 9,886 (22.0) | 9,343 (21.1) |

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black/African American | 23,520 (47.9) | 22,026 (47.5) | 21,285 (47.4) | 20,837 (47.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 9,633 (19.6) | 9,356 (20.2) | 9,065 (20.2) | 9,198 (20.7) |

| White | 13,510 (27.5) | 12,757 (27.5) | 12,419 (27.6) | 12,147 (27.4) |

| Other races/ethnicities | 2,400 (4.9) | 2,264 (4.9) | 2,162 (4.8) | 2,172 (4.9) |

|

| ||||

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| Stage 3 (within 3 months) | 14,188 (28.9) | 13,454 (29.0) | 13,176 (29.3) | 12,737 (28.7) |

| Not stage 32 | 34,873 (71.1) | 32,949 (71.0) | 31,755 (70.7) | 31,616 (71.3) |

|

| ||||

| Transmission Category—Males | ||||

| Male-to-male sexual contact

(MSM) |

27,315 (73.5) | 27,081 (75.7) | 27,021 (77.1) | 27,608 (78.9) |

| Injection drug use

(IDU) |

2,993 (8.1) | 2,542 (7.1) | 2,265 (6.5) | 1,991 (5.7) |

| Male-to-male sexual contact

and injection drug use (MSM- IDU) |

1,720 (4.6) | 1,546 (4.3) | 1,465 (4.2) | 1,291 (3.7) |

| Heterosexual contact | 5,073 (13.7) | 4,572 (12.8) | 4,241 (12.1) | 4,068 (11.6) |

| Transmission Category—Females | ||||

| Injection drug use

(IDU) |

2,003 (16.8) | 1,724 (16.2) | 1,472 (14.9) | 1,324 (14.2) |

| Heterosexual contact | 9,860 (82.8) | 8,831 (83.2) | 8,352 (84.5) | 7,939 (85.0) |

Totals include persons with HIV transmission attributed to infrequent causes such as hemophilia etc.

Includes stage unknown

In the four-year period from 2008 to 2011, the overall average life expectancy after HIV diagnosis in the United States, increased 3.43 years from 25.43 (95% Confidence interval (CI) 25.37–25.49) in 2008, to 28.86 (95% CI 28.80–28.92) in 2011, representing a 13.5% increase over the four year period with an average and fairly steady increase of about 4.5% per year. Life expectancy in each of the 4 years represented a statistically significant increase from the previous year, as determined by the non-overlapping 95% CIs. Although improvements were observed in both sexes, the life expectancy was better for males as compared to females. In each year from 2008 to 2011, males generally had higher life expectancy than females and also experienced a larger increase in life expectancy (3.64 years) compared with females (2.64 years). Persons with late-stage disease at diagnosis (stage 3 [AIDS] had a life expectancy that was on average 6.6 years lower than that for persons with HIV not classified as stage 3. This pattern and the magnitude of difference were consistent across all 4 years (table 2).

Table 2.

Life expectancy of persons diagnosed with HIV infection by year of diagnosis, overall and by selected characteristics, 2008–2011, United States.

| Year of diagnosis | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Diagnoses3 | 49,061 | 46,403 | 44,931 | 44,354 |

|

| ||||

| ELE (95% CI) 4 | ELE (95% CI)2 | ELE (95% CI) 2 | ELE (95% CI) 2 | |

| Overall Life Expectancy | 25.43 (25.37–25.49) |

26.22 (26.16–26.28) |

27.33 (27.27–27.39) |

28.86 (28.8–28.92) |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 26.03 (25.96–26.1) |

26.88 (26.81–26.95) |

28.13 (28.06–28.19) |

29.67 (29.60–29.74) |

| Females | 23.75 (23.62–23.89) |

24.32 (24.19–24.44) |

25.01 (24.88–25.14) |

26.40 (26.27–26.52) |

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black/African American | 23.68 (23.59–23.76) |

24.76 (24.67–24.85) |

26.39 (26.3–26.48) |

28.45 (28.37–28.54) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 28.27 (28.12–28.41) |

28.89 (28.75–29.03) |

29.84 (29.70–29.97) |

30.79 (30.65–30.93) |

| White | 25.69 (25.59–25.8) |

26.26 (26.15–26.36) |

26.85 (26.74–26.95) |

27.77 (27.66–27.88) |

| Other races/ethnicities | 24.71 (24.49–24.93) |

24.32 (24.18–24.46) |

24.83 (24.6–25.05) |

26.13 (25.97–26.29) |

|

| ||||

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| Stage 3 | 20.81 (20.67–20.95) |

21.69 (21.55–21.83) |

22.59 (22.45–22.73) |

24.00 (23.86–24.14) |

| Other than stage 35 | 27.39 (27.32–27.45) |

28.08 (28.02–28.14) |

29.32 (29.26–29.38) |

30.83 (30.78–30.89) |

| Transmission Category—Males | ||||

| Male-to-male sexual contact

(MSM) |

29.31 (29.22-29.41) |

30.23 (30.14-30.32) |

31.18 (31.09-31.27) |

32.30 (32.22-32.39) |

| Injection drug use (IDU) | 17.86 (17.67-18.04) |

17.98 (17.79-18.17) |

18.62 (18.40-18.84) |

20.24 (20.00-20.48) |

| Male-to-male sexual contact and

injection drug use (MSM-IDU) |

23.31 (23.08-23.55) |

23.25 (22.98-23.52) |

24.87 (24.60-25.13) |

26.31 (26.03-26.59) |

| Heterosexual contact | 20.80 (20.63-20.97) |

21.61 (21.43-21.80) |

22.49 (22.32-22.66) |

23.45 (23.28-23.61) |

| Transmission Category—Females | ||||

| Injection drug use (IDU) | 18.70 (18.47-18.94) |

19.76 (19.53-20.00) |

20.45 (20.17-20.72) |

21.36 (21.08-21.64) |

| Heterosexual contact | 25.94 (25.77-26.11) |

26.08 (25.93-26.24) |

26.49 (26.34-26.65) |

27.90 (27.75-28.05) |

Totals include persons with HIV transmission attributed to infrequent causes such as hemophilia etc.

Estimated life expectancy and 95% confidence intervals.

Includes stage unknown

By race/ethnicity, Hispanics/Latinos had a longer life expectancy than any other race/ethnicity throughout 2008–2011 (table 2). The lowest life expectancy in 2008 was observed in blacks (23.68), whereas ‘other races’ (minorities other than blacks and Hispanics/Latinos), had the lowest life expectancy in years 2009–2011. The largest difference between any two races/ethnicities was observed in 2010, when Hispanics/Latinos had a life expectancy 5 years longer than ‘other races’. The difference between life expectancies of Hispanics/Latinos and blacks that was 4.59 years in 2008 shrank steadily over the four-year period to 2.34 years in 2011. When comparing whites with blacks similar shrinking of difference, with eventual reversal was observed. In the year 2008, whites experienced 2.02 years longer life expectancy than blacks. However, this difference consistently reduced in the following years to 0.46 years in 2010 and eventually reversed to 0.68 years favoring blacks (table 2). While all races/ethnicities experienced an improvement in life expectancy 2008–2011, blacks experienced the largest gain (4.78 years), followed by Hispanics/Latinos (2.52 years), whites (2.08 years) and other races (1.42 years). Percent wise, blacks’ life expectancy increased by 20.2%, Hispanics/Latinos 8.9%, whites 8.1% and other races 5.8% (Table 2).

By transmission category, among males, in each year from 2008 to 2010, the longest life expectancy was observed among MSM, followed by males with infection attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and IDU, heterosexual contact, and finally IDU (table 2). In 2011, life expectancy of MSM (32.30, 95% CI 32.22–32.39) was 12.06 years (60%) higher than the life expectancy of males with infection attributed to IDU (20.24, 95% CI 20.0–20.48). Among females, in each of the four years life expectancy was higher among those with infection attributed to heterosexual contact compared with those with infection attributed to IDU. In 2011, females with infection attributed to heterosexual contact had a life expectancy of 27.90, 95% CI 27.75–28.05 vs. 21.36, 95% CI 21.08–21.64, among females who inject drugs. This represents a 6.54 years (31%) higher life expectancy in females with infection attributed to heterosexual contact, compared with females whose HIV infection was attributed to IDU. Persons in all transmission categories and both sexes experienced significant increases in life expectancy from 2008 to 2011. Percent wise, from 2008 to 2011, the largest (14.2%, 2.66 years) and smallest (7.6%, 1.96 years) increases were among females with infection attributed to IDU and heterosexual contact, respectively. Among males, increases of 13.4% (2.39 years), 12.8% (3.00 years), 12.7% (2.65 years) and 10.2% (3.00 years) were observed in males with infection attributed to IDU, male-to-male sexual contact and IDU, heterosexual contact, and male-to-male sexual contact, respectively (Table 2).

Although overall, females had lower life expectancy than males, when limited to either injection-drug use or heterosexual contact, the life expectancy among females was longer than that among males. Females who injected drugs had 1-2 years longer life expectancy than males who injected drugs, while the life expectancy among females with HIV infection attributed to heterosexual contact was about 4-5 years longer than males with infection attributed to heterosexual contact.

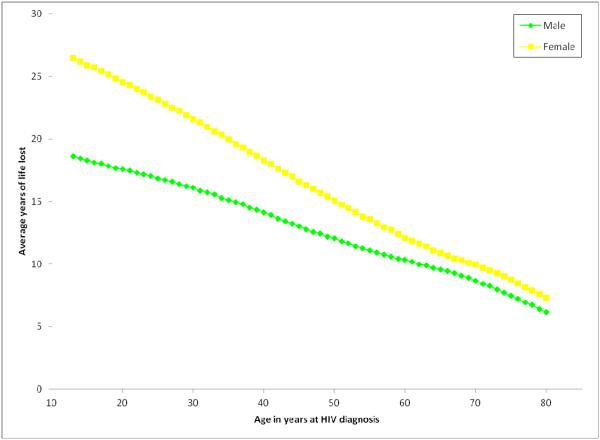

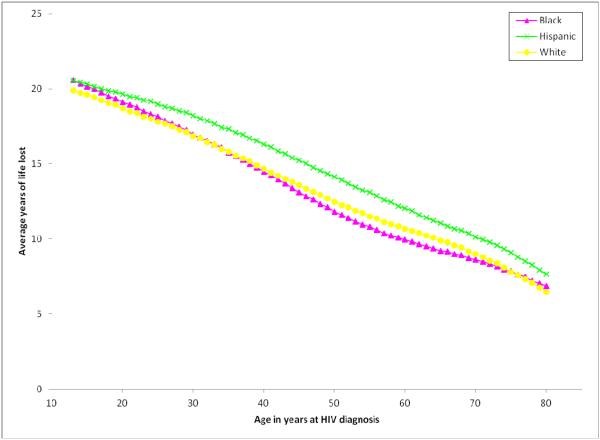

Using the life expectancy in the general population by age, sex and race as reference, in 2010 the AYLL were 12.80 years for males and 16.53 years for females. At ages, 20, 40, 60 and 80 years, males who were diagnosed with an HIV infection in 2010, had AYLL of 17.57, 14.14, 10.35 and 6.16 years respectively. For females diagnosed with HIV infection in 2010, at ages 20,40, 60 and 80 years the AYLL were 24.53, 18.29, 12.08 and 7.31 years respectively. By race/ethnicity, on average blacks (13.26 years) and whites (13.43 years) had fewer AYLL than Hispanic/Latinos (14.72). Life expectancy along with AYLL, among persons diagnosed with HIV infection in year 2010 at five-year age intervals and sex are presented in table 3. Estimated AYLL at age at diagnosis in 2010, by sex and by race/ethnicity are graphically presented in figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Table 3.

Estimated life expectancy and average years of life lost, among persons diagnosed with HIV infection in 2010, by sex and at age at diagnosis by 5 year intervals, United States.

| Estimated Life Expectancy | Average years of life lost | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| 15 | 43.62 | 40.70 | 18.28 | 25.90 |

| 20 | 39.53 | 37.17 | 17.57 | 24.53 |

| 25 | 35.55 | 33.74 | 16.85 | 23.16 |

| 30 | 31.69 | 30.43 | 16.11 | 21.57 |

| 35 | 27.96 | 27.22 | 15.14 | 19.98 |

| 40 | 24.36 | 24.11 | 14.14 | 18.29 |

| 45 | 20.89 | 21.08 | 13.01 | 16.62 |

| 50 | 17.54 | 18.12 | 12.06 | 15.08 |

| 55 | 14.30 | 15.21 | 11.10 | 13.59 |

| 60 | 11.15 | 12.32 | 10.35 | 12.08 |

| 65 | 8.12 | 9.42 | 9.58 | 10.88 |

| 70 | 5.53 | 6.54 | 8.67 | 9.96 |

| 75 | 3.52 | 4.15 | 7.48 | 8.75 |

| 80 | 2.04 | 2.39 | 6.16 | 7.31 |

Figure 1.

Estimated average years of life lost after HIV diagnosis in 2010, by sex, United States.

Figure 2.

Estimated average years of life lost after HIV diagnosis in 2010, by race/ethnicity, United States.

Discussion

The life expectancy of people who were diagnosed with an HIV infection during 2008–2011 presented in this paper represents the first estimates using data from all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (D.C.). The results show that the life expectancy improved over the four-year interval 2008– 2011 for all populations from 25.43 years in 2008 to 28.86 years in 2011, representing an increase in life expectancy of 3.43 years or 13.5%. While similar life expectancy estimates have been reported by other studies in the era of HAART 9,16, the direct comparison of results is difficult, as the published estimates in contemporary literature show large variation because of varying methodologies, time spans studied, and populations of interest. Our results also indicate that during 2008–2011, the life expectancy for persons diagnosed with HIV infection has continued to improve since the publication of last estimates using more limited HIV surveillance data from 25 states, that compared pre- and post-HAART eras 1.

MSM consistently had longer life expectancy than persons with HIV infection attributed to any other transmission category and on average expected to live more than a decade longer than persons with HIV infection attributed to IDU; who in turn had a worse life expectancy than persons in any other transmission category, consistent with earlier findings 17. The high mortality among persons who inject drug may be due to other risk factors related to IDU that lead to premature mortality, such as cigarette smoking, comorbidities, drug overdose and barriers to accessing HIV care and medications . A recent study found that among a cohort of approximately 18,000 HIV-infected individuals, smokers suffered from higher mortality than non-smokers (mortality rate ratio; 1.94, 95% CI 1.56–2.41) 18,19. Persons who inject drugs are also more likely to have other comorbidities, such as hepatitis-C infection and mental illnesses, and also face health-care access challenges 20-23. A study in New York City found that among HIV-HCV co-infected individuals, 60% had their infection attributed to injection drug use 22.

Additionally, the role of social determinants of health such as low education, high poverty, discrimination and low access to and poor retention in health care that negatively affect life expectancy cannot be ruled out 24-28. All these factors have been shown to have an association with IDU29-31

Life expectancy of females was lower than that of males, and since life expectancy of females in the general population is longer than that of males, the AYLLS for females in 2010, were higher than for males at all ages at diagnosis. We found that in 2011 the life expectancy of younger females (<40 years at HIV diagnosis) was less than that of males that were the same age at HIV diagnosis. However this pattern reversed in older age groups, with females who were 40 years of age or older at HIV diagnosis, had slightly better life expectancy than men who were diagnosed at age 40 or older. Since men with infection attributed to male-to-male sexual contact have longer life expectancy than men with infection attributed to other causes and because a large proportion of HIV-infected MSM are diagnosed at a young age 32, it helps explain the better life expectancy seen among males in the younger age groups. This explanation is further supported by the fact that when comparisons across sex are made within the transmission categories common to both sexes, i.e., injection drug use and heterosexual contact, females have longer life expectancy than males (table 2).

Hispanics/Latinos had higher AYLL in 2010, than either blacks or whites, and the difference between Hispanics and whites, and Hispanics and blacks, increased slightly with increasing age at diagnosis until about age 50 and then reduced a little as age at diagnosis pushed into older years (Figure 2). Hispanics/Latinos are more likely to enter care late and are more likely to discontinue treatment than whites 33,34, which helps explain the higher AYLL among Hispanics/Latinos infected with HIV. Although life expectancy of blacks in the general population is slightly lower than that of whites, and blacks with diagnosed HIV have a higher rate of death than whites diagnosed with HIV, the life expectancy of the two groups was similar, with blacks showing a slightly longer life expectancy than whites in 2011. The apparent paradox is explained by the fact that HIV tends to be diagnosed at an earlier age in blacks as compared to whites. Indeed, among person diagnosed with HIV in 2011; among blacks 27.4% were diagnosed before reaching 25 years of age, and 53.4% were diagnosed before age 35. The percentages among whites were 13.6 and 39.8 respectively 35.

The results of these analyses can be a useful resource for clinicians as well as policy makers. They can guide patient-provider communications on prognoses and expectations after an HIV diagnosis; whereas policy makers may find these results to be a useful guide for estimating costs for care and resource allocation.

Our estimates’ biggest strength is that they are based on data from the entire country with documented high completeness of reporting, instead of a sub-sample of states. However, there still are a few limitations of our analysis. Not all HIV diagnoses may have been included, as some states offer anonymous HIV testing, which are not reported to HIV surveillance. Additionally person who are HIV infected, but not yet diagnosed are also not included in the surveillance data. However these factors are unlikely to have a significant impact on our estimates as it has been estimated that HIV-infected, yet undiagnosed persons make up only about 12.8% of the total persons infected with HIV in the United Sates 36.

Another limitation of our estimates is that we did not take into account the influence of comorbidities, HIV treatment and viral load suppression status, all of which influence mortality and thus the life expectancy. Also, some deaths among persons with HIV may not yet have been reported to surveillance. Therefore our estimates could be an over or underestimate of the true life expectancy after HIV diagnosis. However, we do not expect any systematic association with any of the factors that can lead to net over- or under-estimation of life expectancy. For this reason and because we used a very large dataset covering the entire country with high degree of completeness, we expect our estimates to be reliable estimates.

In summary, our analysis shows that the persons diagnosed with an HIV infection during 2008–2011, experience better life expectancy than those diagnosed in previous years and that the life expectancy continued to improve during 2008–2011, with consequent reduction in AYLL, overall and across all sex, race and transmission categories. However, the life expectancy of PLWDH still remains shorter than the life expectancy of the general population of the United States. While further improvements in the life expectancy of HIV-infected person is possible as treatment regimens continue to evolve, with improvements the role of other factors (e.g. early diagnosis, availability and access to treatment, adherence to treatment, side effects of antiretroviral therapy etc.) come to play a greater role in determining the period one can expect to live after an HIV diagnosis 37-40. Our analysis demonstrates that the life expectancy after HIV diagnosis has continued to improve in HAART era. As the proportion of persons living with HIV who know their status (i.e. diagnosed) continue to increase and the access to HAART and adherence to treatment continue to improve, more accurate estimates should be generated in the future for continued monitoring of the progress of the status of the disease. Not all sub-groups show similar improvements in life expectancy, therefore individualized treatment plans, taking into consideration the actual needs and challenges of each subgroup can help improve life expectancy in these subgroups and reduce disparities.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the HIV surveillance staff in all jurisdictions within the United States for their efforts in collection of data used in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Supported by US Government.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusion presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Poster presented at: CROI 2015 (February 23–26, 2015), Seattle, WA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrison KM, Song R, Zhang X. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Jan;53(1):124–130. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b563e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Published July 2010; http;//www.WhiteHouse.gov/administration/eop/omap/nhas. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- 3.Healthy People 2020 [internet] http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default. Accessed July 10th, 2015.

- 4.Gardner JW, Sanborn JS. Years of potential life lost (YPLL)--what does it measure? Epidemiology. 1990 Jul;1(4):322–329. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnet NG, Jefferies SJ, Benson RJ, et al. Years of life lost (YLL) from cancer is an important measure of population burden--and should be considered when allocating research funds. Br J Cancer. 2005 Jan 31;92(2):241–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson LF, Mossong J, Dorrington RE, et al. Life expectancies of South African adults starting antiretroviral treatment: collaborative analysis of cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills EJ, Bakanda C, Birungi J, et al. Life expectancy of persons receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a cohort analysis from Uganda. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Aug 16;155(4):209–216. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammadi-Moein HR, Maracy MR, Tayeri K. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on data from the counseling center for behavioral diseases. J Res Med Sci. 2013 Dec;18(12):1040–1045. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakagawa F, Lodwick RK, Smith CJ, et al. Projected life expectancy of people with HIV according to timing of diagnosis. AIDS. 2012 Jan 28;26(3):335–343. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dcec9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Sighem AI, Gras LA, Reiss P, et al. Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2010 Jun 19;24(10):1527–1535. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tancredi M, Waldman E. Survival of AIDS patients in Sao Paulo-Brazil in the pre- and post-HAART eras: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Nov 15;14(1):599. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green TA. Using surveillance data to monitor trends in the AIDS epidemic. Stat Med. 1998 Jan 30;17(2):143–154. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980130)17:2<143::aid-sim757>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison KM, Kajese T, Hall HI, et al. Risk factor redistribution of the national HIV/AIDS surveillance data: an alternative approach. Public Health Rep. 2008 Sep-Oct;123(5):618–627. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arias E. United States life tables, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014 Nov;63(7):1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song R, Qin G, Harrison KM, et al. Modelling survival after diagnosis of a specific disease based on case surveillance data. Int J Stat Med Res. 2014;3(1):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohse N, Hansen AB, Pedersen G, et al. Survival of persons with and without HIV infection in Denmark, - Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jan 16;146(2):87–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antiretroviral Therapy. Cohort C. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008 Jul 26;372(9635):293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Mar;56(5):727–734. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helleberg M, May MT, Ingle SM, et al. Smoking and life expectancy among HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America. AIDS. 2015 Jan 14;29(2):221–229. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chander G, Himelhoch S, Moore RD. Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in HIV-positive patients: epidemiology and impact on antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2006;66(6):769–789. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monga HK, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Breaux K, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Infection-Related Morbidity and Mortality among Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001 Jul 15;33(2):240–247. doi: 10.1086/321819. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prussing C, Chan C, Pinchoff J, et al. HIV and viral hepatitis co-infection in New York City, 2000-2010: prevalence and case characteristics. Epidemiol Infect. 2015 May;143(7):1408–1416. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814002209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinsler JJ, Wong MD, Sayles JN, et al. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007 Aug;21(8):584–592. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, et al. Impact of HIV-Related Stigma on Health Behaviors and Psychological Adjustment Among HIV-Positive Men and Women. AIDS and behavior. 2006;10(5):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2197-0. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dean HD, Fenton KA. Addressing social determinants of health in the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis. Public Health Rep. 2010 Jul-Aug;125(Suppl 4):1–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song R, Hall HI, Harrison KM, et al. Identifying the impact of social determinants of health on disease rates using correlation analysis of area-based summary information. Public Health Rep. 2011 Sep-Oct;126(Suppl 3):70–80. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PA, et al. BArriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA. 1998;280(6):547–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S135–S145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, et al. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Stress, and Drug Use among Adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(2):151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams CT, Latkin CA. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. Am J Prev Med. 2007 Jun;32(6 Suppl):S203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf. Accessed July 24th, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dennis AM, Napravnik S, Seña AC, et al. Late Entry to HIV Care Among Latinos Compared With Non-Latinos in a Southeastern US Cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011 2011 Sep 1;53(5):480–487. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gwadz M, Applegate E, Cleland C, et al. HIV-Infected Individuals Who Delay, Decline, or Discontinue Antiretroviral Therapy: Comparing Clinic- and Peer-Recruited Cohorts. Front Public Health. 2014;2:81. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Surveillance Report. 2011;23 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2011_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_23.pdf. Accessed January 10th, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall HI, An Q, Tang T, et al. Prevalence of Diagnosed and Undiagnosed HIV Infection - United States, - MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Jun 26;64(24):657–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwapong GD, Boateng D, Agyei-Baffour P, et al. Health service barriers to HIV testing and counseling among pregnant women attending Antenatal Clinic; a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:267. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monsuez JJ, Charniot JC, Escaut L, et al. HIV-associated vascular diseases: structural and functional changes, clinical implications. Int J Cardiol. 2009 Apr 17;133(3):293–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Post FA, Holt SG. Recent developments in HIV and the kidney. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;22(1):43–48. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328320ffec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suligoi B, Zucchetto A, Grande E, et al. Risk factors for early mortality after AIDS in the cART era: A population-based cohort study in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:229. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0960-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]