Abstract

This review explores how the integration of advanced imaging methods with high quality anatomic images significantly improves the characterization, target definition, assessment of response to therapy, and overall management of patients with high-grade glioma. Metrics derived from diffusion, perfusion, and susceptibility weighted MR imaging in conjunction with MR spectroscopic imaging, allows us to characterize regions of edema, hypoxia, increased cellularity, and necrosis within heterogeneous tumor and surrounding brain tissue. Quantification of such measures may provide a more reliable initial representation of tumor delineation and response to therapy than changes in the contrast enhancing or T2 lesion alone and have a significant impact on targeting resection, planning radiation, and assessing treatment effectiveness. In the long-term, implementation of these imaging methodologies can also aid in the identification of recurrent tumor and its differentiation from treatment-related confounds and facilitate the detection of radiation-induced vascular injury in otherwise normal appearing brain tissue.

INTRODUCTION

The superior soft tissue contrast in images obtained using Magnetic Resonance (MR) has made it an important modality for planning radiation treatments and for following the response to therapy in patients with high grade glioma. Despite their widespread use, standard T1-weighted and T2-weighted MR images are increasingly being recognized as providing ambiguous and sometimes misleading information about the location and aggressiveness of the lesion1. It is clear that the standard approach of defining the region of contrast enhancement (CE) on post-Gadolinium T1-weighted images as the macroscopic tumor and surrounding hyperintensity on T2-weighted images as being primarily edema is an over-simplification that needs to be modified to reflect the biological properties of the lesion and the treatment history2.

Pseudo-progression has become a confounding factor for as many as a third of the patients with newly diagnosed high grade glioma who are treated with temozolomide and external beam radiation3-7. This is observed as an increase in the spatial extent of the CE lesion on post-radiation scans that would normally be interpreted as recurrent tumor but then decreases again without a change in treatment. Knowing whether to recommend continued surveillance or an alternative therapy is a difficult dilemma to resolve without having a more accurate picture of the true underlying tumor burden. While a number of different imaging methods have been proposed to aid in making this distinction,1,7 there is not yet a definitive solution.

With the integration of bevacizumab and other anti-angiogenic agents into treatment strategies for high grade glioma8-11, the phenomenon of pseudo-response has been identified as another confounding factor for the interpretation of T1 and T2-weighted MR images. In this case, the CE lesion can exhibit a substantial decrease in size due to a reduction in vascular permeability that is associated with normalization of the vasculature5. This occurs within a few days after the initiation of treatment and may be sustained for several months. A reduction in the size of the T2 lesion may also be observed within one to two months after treatment, which is associated with reduced edema and radiation-induced necrosis8. Note that none of these changes have a direct effect on the number of tumor cells and there have been reports that the residual disease becomes more infiltrative and is less likely to respond to other therapeutic agents at recurrence10,11. Obtaining imaging data that help to make an assessment of how the biology of the tumor is being affected would be extremely valuable for optimizing patient care.

The RANO working group has recently proposed criteria for assessing treatment response in high grade glioma12 that consider changes in the size of both the CE and T2 lesions. While this is a first step in modifying the definition of tumor burden, more needs to done in order to add more biologically relevant imaging parameters1. An important pre-requisite to making such a change is to obtain a consensus on which advanced imaging methods provide the most relevant information. In the following, we present an overview of advanced MR imaging methods that have been shown to contribute to the assessment of tumor burden and treatment effects, with an emphasis on how they have been used to address issues that are important for planning and monitoring radiation therapy. While we recognize the potential value of other imaging modalities such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in assessing biological behavior13-15, we feel that the widespread availability of MR and its ability to obtain many different kinds of images within a single examination make it a particularly attractive option.

ADVANCED MR IMAGING METHODS OF INTEREST

MR imaging technologies that are relevant to planning treatment and evaluating radiation effects include strategies for assessing microvasculature, for monitoring the formation of microbleeds, for evaluating disruptions in tissue architecture, and for observing changes in cellular metabolism. These have been implemented on clinical MR scanners and are available to users without the need for specialized hardware or contrast agents. Inconsistencies between results that have been obtained reflect variations in implementations of specific pulse sequences, data acquisition parameters, or post-processing methods that have been selected. While these could, in principle, be resolved, it will require a consensus from the oncology community in order to define and implement standard procedures. The following represent multi-parametric imaging methods that are under consideration.

Vascular Imaging Using Gadolinium Contrast Agents

Approaches for accentuating subtle changes in the leakiness of the vasculature are to either perform a weighted subtraction of the current post- minus pre-Gadolinium T1 weighted images to give T1-difference contrast16 or to delay obtaining the post-contrast images to about 1 hour after injection17. Both strategies have been reported as accentuating the contrast between tumor and normal tissue in order to provide a more consistent estimate of the contrast enhancing tumor burden. It is not yet clear how sensitive they are to variations in scan parameters and differences in the type or dose of Gadolinium agent that is applied.

Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) imaging has been used to provide more quantitative evaluation of vascular permeability by assessing changes in T1-weighted contrast over a period of 5-10 minutes after the injection of the Gadolinium18,19. The resulting images are analyzed with a pharmacodynamic model to provide maps of biologically relevant parameters20. For cases where the emphasis is on changes in cerebral blood volume, an alternative is to obtain dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) images during a rapid bolus of Gadolinium18,21. The resulting T2*-weighted data are analyzed to obtain cerebral blood volume relative to normal brain (nCBV). A number of different models and acquisition strategies have been applied to analyze DCE and DSC images in clinical trials22-25, with a particular emphasis on evaluating short-term changes that are associated with anti-angiogenic therapies26-28.

Susceptibility Weighted Imaging (SWI)

High resolution SWI, in addition to visualizing microvasculature, is a powerful tool for imaging hemosiderin-containing hemorrhagic foci29. Image contrast is based upon differences in susceptibility effects caused by levels of iron containing compounds such as hemosiderin and dexoyhemoglobin in venous blood. The post-processing technique utilizes the phase signal to improve detection of structures such as blood vessels and microbleeds and emphasize contrast in the magnitude image by multiplying it with a masked, high-pass filtered phase image30. Employing parallel imaging techniques allows for the acquisition of images at 500μ resolution with full supratentorial brain coverage in less than 7 minutes at 3T31. SWI benefits from the heightened susceptibility contrast available with higher field strength scanners and can be used for routine patient studies.

Diffusion Weighted Imaging

This is applied to patients with glioma in order to estimate the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of tissue water, which has been linked to tumor cellularity32. Studies from our own and other groups have shown that there are differences in ADC between histological subtypes of glioma33 and that a number of metrics involving the ADC are associated with worse outcome for patients with GBM34-41. Examples are the volume within the T2 lesion that has ADC less than 1.5 times the value in normal brain34 and alterations in what have been called Functional Diffusion Maps (FDMs)38,40,43. High Angular Resolution Diffusion Imaging (HARDI) is a more advanced method that is used in the clinical setting for planning surgical resection and assessing the disruptive impact of the tumor on normal brain architecture44. Parameters obtained from multi-compartmental modeling of diffusion parameters45-47 have also been proposed as metrics for assessing treatment-induced changes in both tumor and normal brain.

Metabolic Imaging

A number of studies have highlighted the potential benefits of using H-1 MR spectroscopy to estimate levels of metabolites in brain tumors48. When combined with similar spatial localization techniques that are used in generating anatomic MR images, this strategy can be used to produce maps of the variations in levels of choline containing compounds (Cho), creatine (Cre), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), lactate (Lac), and mobile lipids (Lip). With improvements in scanner hardware and software the acquisition time for volumetric data is on the order of 5-10 minutes and the spatial resolution of the voxels obtained is typically 0.5-1cc49. By correlating in vivo H-1 metabolic imaging parameters with ex vivo histological characteristics from image-guided tissue samples, we have shown that regions with elevated Cho and reduced NAA relative to normal brain have a high probability of corresponding to tumor50,51. The Cho to NAA index (CNI) is a metric that we have developed to describe such changes52. We have also shown that lesions with elevated Lac and Lip have high grade histology with shorter progression free and overall survival33-35.

APPLICATIONS

In the following we consider several clinically important issues that benefit by using the multi-parametric MR imaging approaches described above in order to provide improved visualization of the biological properties within the lesion.

Characterizing the Lesion and Targeting Resection

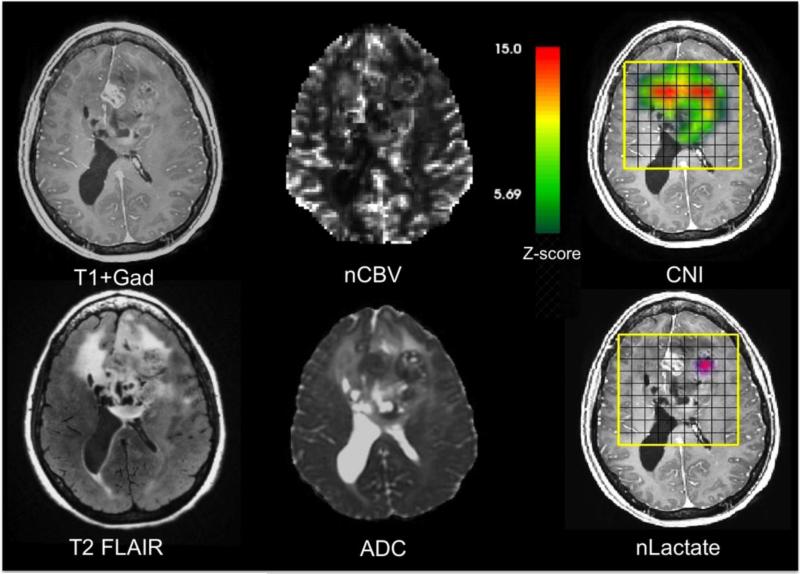

A critical role for MR imaging is to highlight regions that the surgeon should target for tissue sampling in order to be able to assess representative histological and, where appropriate, molecular properties of the tumor. A number of studies have demonstrated the value of this approach50,53,54. Figure 1 provides an example of the high degree of heterogeneity that may be present in multi-parametric, pre-surgery MR images from a patient with a suspected GBM. The post-contrast T1-weighted image shows a focus of CE near the midline, as well as larger non-enhancing (NE) regions of the mass that are hypo- and isointense relative to normal appearing white matter. The T2-weighted FLAIR image is similarly heterogeneous, with some areas that are very bright and may be interpreted as being due to edema, and others that have only slightly higher intensity than normal brain. The nCBV image, which was estimated from DSC imaging data, indicates that there is increased vasculature in the right and left hemispheres, as well as the NE portion that crosses the corpus callosum. The ADC image shows two circular foci of restricted diffusion, one that corresponds to the CE focus and one that is in the NE portion of the lesion in the left hemisphere. The areas with highest CNI images are to the left and right of the CE region, but only the one on the left has elevated lactate.

Figure 1.

Anatomic, diffusion, perfusion, and metabolic images from a patient with a suspected GBM obtained prior to surgical resection. The post-Gadolinium T1-weighted image shows a relatively small region of enhancement, but the T2-weighted FLAIR image is much larger and very heterogeneous. The normalized blood volume image (nCBV) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) have a number of foci with abnormal intensity. The CNI color overlay is scaled on a range of 1-15 with a cut-off of 2 standard deviations above normal. The lactate color overlay shows a single focus if increased intensity.

Overall, these data are consistent with there being infiltrative tumor crossing the corpus callosum and three heterogeneous foci of tumor that have varied physiological properties. The focus of tumor in the right hemisphere is NE, has increased cellularity and highly abnormal metabolism, but is probably not yet hypoxic (moderate nADC, very high CNI, but no lactate). The medial, CE focus of tumor is highly cellular and has abnormal metabolism (low nADC and abnormal but slightly lower CNI, with no lactate). The left focus of NE tumor is highly cellular, with some hypoxia and a small region of necrosis (low overall ADC with a small area that is high, very high CNI and elevated lactate). These findings have implications not only for tissue sampling and planning the extent of resection, but also for understanding the characteristics of residual tumor that will be the target for radiation and other therapies.

Planning Radiation Therapy

Accurate definition of the spatial extent of tumor is critical for defining the radiation target. In studies that compared differences in the CE, T2, and metabolic lesions for grade 3 glioma and GBM55,56, we showed that (i) the metabolic lesion was usually substantially larger than the CE region and (ii) although it may extend outside the boundaries of the T2 lesion, the metabolic abnormality is generally smaller in overall volume. This suggests that the common practice of using the T2 lesion plus a 2-3cm margin as the overall target volume for external beam radiation therapy (RT) and the CE lesion as the boost volume may both undertreat areas of non-enhancing tumor and over-treat regions of surrounding normal brain. The latter may cause damage to normal brain and lead to an increased formation of gliosis and edema that complicates the interpretation of the conventional MR images obtained in follow-up examinations. Taking these findings into account, it seems appropriate to consider the union of the region with CNI>3 and the CE volume as the area that correspond to gross tumor and needs to be treated with the highest possible dose58. For large, non-enhancing lesions that have high ADC and are thought to have a lot of edema, we recommend using the region with CNI>2 rather than the entire T2 lesion as the basis for defining the overall target volume in order to limit the damage to normal brain59. A recent study that examined the impact of including the region with Cho/NAA>2 in the boost volume for IMRT confirmed the feasibility of the approach and recommended that it should be used for future treatment plans60.

Another finding in the context of defining the target for external beam radiation therapy was that regions of highly restricted diffusion (low ADC) in the post-operative scan that correspond to ischemic injury may temporarily become enhancing61. This can confuse the assessment of tumor for treatment planning scans or be misinterpreted as corresponding to tumor progression62. Future studies may also want to consider whether it is important to add regions of the T2 lesion where nADC is thought to correspond to highly cellular tumor (ie ADC <1200) into the definition of the boost volume. This would be important because diffusion weighted imaging is more commonly applied in a clinical setting and could be used in cases where the H-1 MRSI or other metabolic data are not available. Note that in a recent study that correlated pre-operative nCBV and ADC values from image-guided tissue samples with histological findings, low ADC values in the NE tumor was associated with higher tumor scores, while high values of nCBV were associated with higher tumor scores in the enhancing tumor53.

The CNI lesion may also be important for defining the target volume for gamma knife (GK) radiosurgery or other forms of re-irradiation at the time of recurrence. Our early studies clearly showed that patients with CNI lesions that extended outside of the target volume for GK radiosurgery had worse overall survival than patients for whom the CNI lesion was fully treated63,64. While this may make the size of the target volume too large to be treated with such focal irradiation, making that determination would avoid having a patient undergo a procedure that is likely to be ineffective and allow early adoption of an alternative strategy64.

Assessment of Treatment Effectiveness

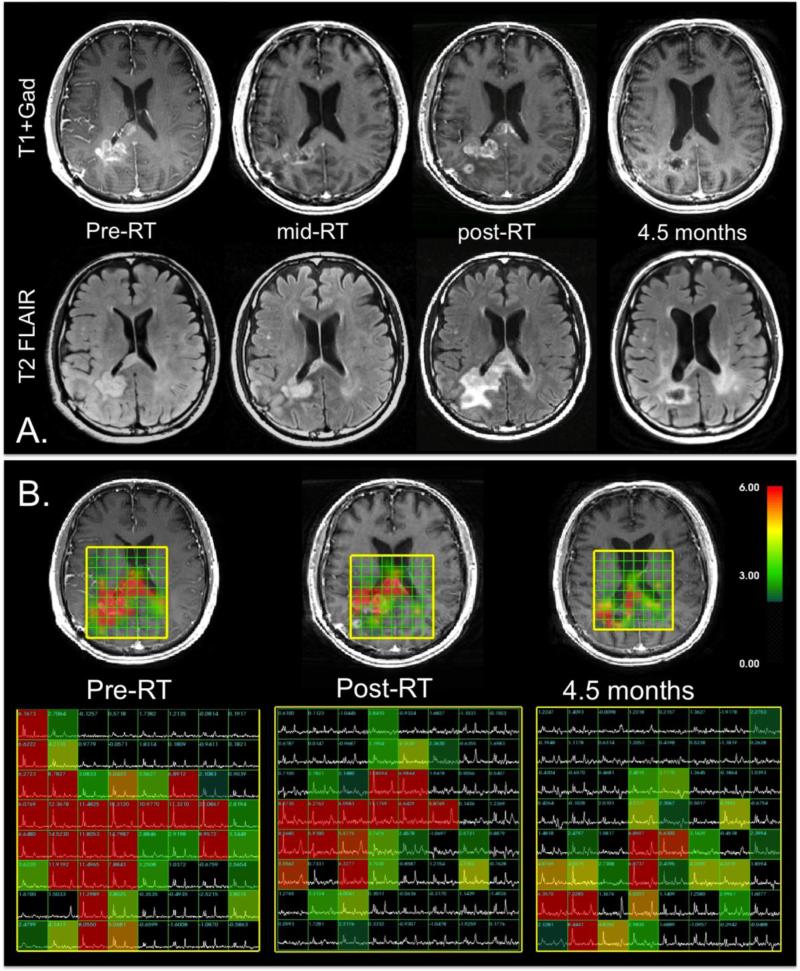

As was indicated previously, a number of different diffusion33-43, perfusion66-71 and metabolic33-35,72 imaging parameters have been proposed for evaluating response to therapy and predicting progression free or overall survival. The assessment of treatment effectiveness is especially complex when a combination of different agents is given. Figure 2A shows an example of the anatomic images obtained from a patient with a newly diagnosed GBM who was participating in a Phase II clinical trial of external beam RT, temozolomide, and enzastaurin. The baseline, immediate pre-RT scan shows a CE lesion on the right hemisphere that is starting to cross the corpus callosum. In the left hemisphere there is a NE region that is only slightly higher in intensity than normal brain. At one month into RT, the CE region has shrunk substantially and there is reduced mass effect in the right hemisphere. In the post-RT scan, the CE lesion has increased in size and become multi-focal. The T2 lesion is also much larger. By the time of the next follow-up, both the CE and T2 lesion have significantly reduced in size again, indicating that the post-RT changes were associated with pseudo- rather than true progression.

Figure 2.

Anatomic and metabolic imaging from four serial examinations of a patient with a GBM being treated with RT, temozolomide and enzastaurin. A.) T1-weighted post-Gadolinium images (top) and T2-weighted FLAIR images (bottom). The post-RT exam shows increases in the CE and T2 lesions, which subsequently reduce again, indicating that these changes were due to pseudoprogression. B.) Metabolic imaging data. The CNI overlays have a cut-off at a value of 2 and are all on the same color scale. The extent of the region of abnormal CNI is much larger than the anatomic lesion and decreases with time and intensity, which indicates that the tumor is responding to therapy during this period.

Figure 2B shows serial metabolic imaging data from the same patient for the baseline, post-RT, and 4.5 month scans. The color overlays represent the values of CNI that are more than 2 standard deviations above normal brain. Note that the metabolic lesion is more extensive than the region of CE at all three time points and with continual decrease in its spatial extent with time. The maximum CNI values were 18.3, 11.7, and 8.4 standard deviations above normal at successive time points. In addition to providing the correct interpretation of the post-RT exam as being due to pseudoprogression, the metabolic data are consistent with there having being a response to therapy. It should be noted, however, that despite the reduction in size of the metabolic lesion, the metabolic data indicated that there was substantial residual tumor at the 4.5 month scan, which extended across the corpus callosum. This demonstrates the potential for resolving ambiguities in standard imaging by taking a multi-modality approach. In our analysis of serial anatomic and metabolic imaging data from patients participating in this and other Phase II clinical trials of patients with newly diagnosed GBM, we found that the volume of the region with CNI>2, the maximum CNI value, and the amount of lactate at baseline and post-RT scans were associated with overall survival72. This suggests that a multi-modality MR exam that includes anatomic, diffusion, perfusion, and metabolic imaging would be helpful in providing a more complete picture of early treatment-induced changes in the lesion and surrounding tissue73.

Detection of Recurrent Tumor

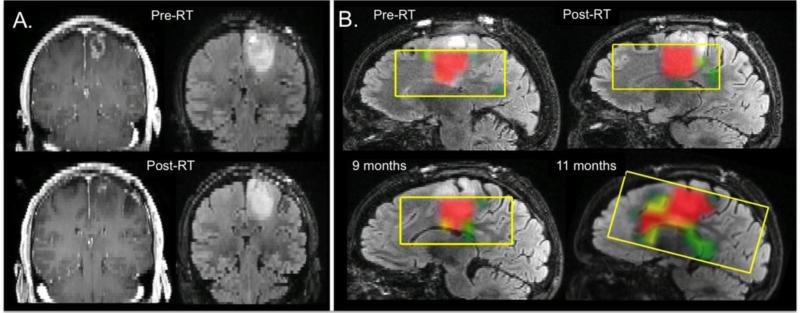

Another critical issue for making decisions about patient care is in determining whether changes seen on anatomic images are due to treatment effect or recurrent tumor. Perfusion imaging parameters have been reported as helping to make this distinction, with higher nCBV being indicative of tumor55,74-78. A multi-modality approach that includes diffusion imaging and metabolic imaging with H-1 MRSI or PET has also been considered79-81. Figure 3 shows an example of the spatial extent and evolution of the metabolic lesion for a patient with a newly diagnosed GBM who was participating in a clinical trial of RT, temozolomide, bevacizumab, and erlotinib. The coronal baseline (pre-RT) and post-RT anatomic images show that there was a substantial reduction in the CE lesion. The relatively well-circumscribed T2 lesion is much larger and shows a relatively small decrease in size. As is shown on the sagittal color overlays of the CNI values, the T2 lesion had a highly abnormal metabolic signature that was relatively stable in size for the first 9 months but then at 11 months expanded significantly and was infiltrating along the corpus callosum. Tumor progression was confirmed by tissue samples obtained at a subsequent surgical resection. These data indicate that the original reduction in the CE lesion was due to pseudoresponse and that metabolic parameters may be particularly important for assessing changes in the spatial extent of NE tumor.

Figure 3.

Coronal T1-weighted post-Gadolinium images and T2-weighted FLAIR images from the pre-RT and post-RT exams showing a relatively small CE lesion, which reduced significantly during treatment. The T2 lesion is much larger and extends inferior to the CE region. The sagittal color overlays of the CNI maps, which are on the same scale as those shown in Figure 3, indicate that the T2 lesion has CNI values of 6 or greater, are relatively stable during the first 9 months, and then begin to expand along the corpus callosum. There was no enhancement at this time but the patient was assessed as having progressed based upon an increase in the T2 lesion. Tumor recurrence was confirmed by subsequent surgical resection.

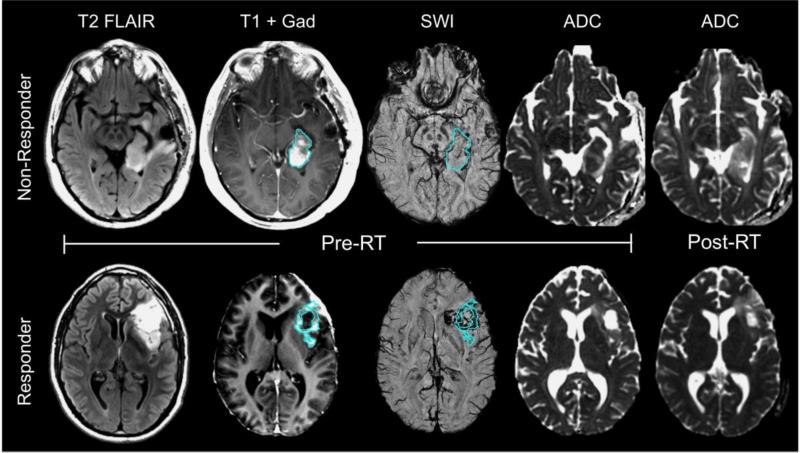

Another metric that has been reported as being able to distinguish recurrent tumor from necrosis is the ADC82,83, with low values being indicative of tumor and high values of necrosis. For anti-VEGF treatments, where the CE lesion is substantially reduced and progression may be represented by an increase in the T2 lesion, regions within the T2 lesion that have reduced ADC are thought to correspond to recurrent tumor. In support of these results, in patients with high grade glioma who were being treated with standard of care therapy there were significantly reduced ADC histogram measures within the enhancing volume on CE-SWI compared to those with stable disease84. On the other hand, an increase in post-RT ADC metrics was associated with a shorter progression free survival for patients treated with either temozolomide alone71 or with adjuvant enzastaurin41 as illustrated in Figure 4. Baseline SWI was also shown to be associated with overall and progression free survival for the latter therapy group, with larger percentages of SWI hypointense signal within the CE lesion acting as a protective factor (Figure 4)85.

Figure 4.

Anatomic (T2 FLAIR and T1 post-Gad), SWI, and diffusion (ADC) images of 2 patients with glioblastomas treated with RT, temozolomide, and enzastaurin. The patient in the top row who did not respond to this therapeutic regime and progressed only 3 months after initiating treatment had less %SWI signal hypointensity within the CE lesion at baseline and an increase in ADC after the completion of RT, while the patient in the bottom row who responded to the therapy had a larger percentage of SWI hypointense signal within the CE lesion, similar ADC values pre- and post-RT, and did not show signs of tumor progression until after a year from initiating therapy. The volumes of T2 hyperintensity and CE lesion similarly decreased at 2 months for both patients.

Late Radiation Effects

The initial histologic response to RT involves white matter pathology ranging from demyelination to coagulative necrosis and cortical atrophy86. In the intermediate- and long-term horizons after radiation, characteristic vascular abnormalities in the form of arteriopathy and endothelial proliferation ensue, resulting in progressive impairment in cerebral microcirculation and in the formation of cavernous angiomas that may slowly or acutely hemorrhage87. Findings on MRI have revealed changes in blood vessel permeability88, the volume of T2-hyperintensity89, and fractional anisotropy values within normal-appearing white matter90,91 during the first 6 months after the completion of RT. Although the clinical manifestation of these events usually begins anywhere from 6 months to several years after receiving RT, the presentation of obvious neurologic deterioration can result many months or even years later, often coinciding with the appearance of cerebral microbleeds in otherwise normal-appearing brain parenchyma on T2*-weighted gradient echo MRI92. Microbleeds are defined as hemosiderin-containing deposits that accumulate around vessels and on histopathological analyses reflect a spectrum of microvascular injury that includes endothelial damage, fibrinoid necrosis, luminal narrowing, and occlusion93,94.

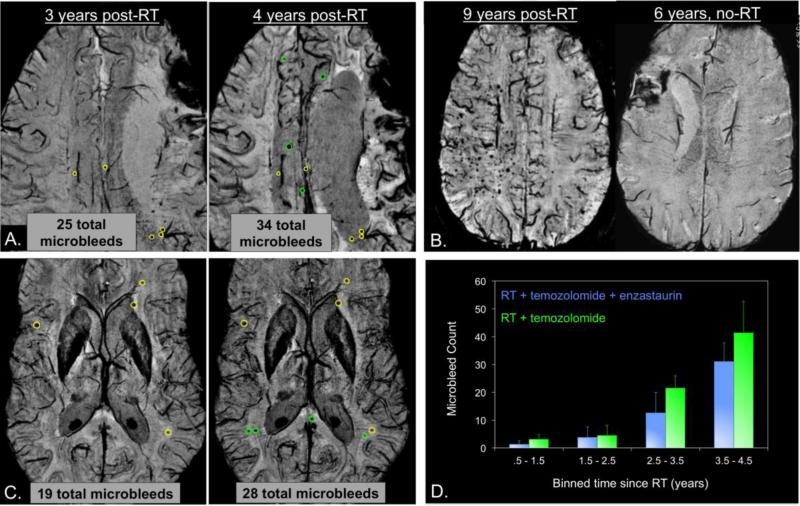

In addition to its early on association with response to therapy, SWI has been employed to detect delayed vascular injury in the form of microbleeds as shown in Figure 5. Retrospective evaluation of SWI in patients with long-term stable gliomas who were treated with x-RT many years prior to the time of imaging has revealed hemorrhagic lesions in all of the 20 irradiated adult patients studied92. These microbleeds appeared in irradiated patients as early as 15 months after receiving radiotherapy, but not in patients treated only with chemotherapy (Figure 5B). The prevalence of these lesions increases as a function of time since a patient received RT, with as few as 2-5 microbleeds observed 2 years after the initiation of RT and over 200 detected 10 years after irradiation (Figure 5B). Subsequent serial analysis of individual patients revealed an increased rate of microbleed formation after 2 years post-RT onset compared to before 2 years, with the concomitant and adjuvant administration of an anti-angiogenic agent at the time of radiation resulting in a radioprotective effect, whereby both the number of microbleeds and initial rate of their appearance was reduced (Figure 5C&D). In children treated with whole-brain radiation for a medulloblastoma, microbleeds were detected with SWI as early as 4 months after treatment95, although no studies to date have been able to show relationships between the number of microbleeds and age at the time of radiation or brain location.

Figure 5.

Formation of radiation-induced microbleeds. A.) A representative patient with a grade 3 oligodendroglioma who received RT and temozolomide post-surgical resection of their tumor. 9 new microbleeds formed between 3 and 4 years post-RT (green circles denote newly-formed microbleeds). B.) Another irradiated grade 3 glioma 9 years post-RT (left) compared to a low grade glioma who did not develop any microbleeds 6 years after receiving temozolomide (right). C.) A representative patient with a grade 4 glioma who received RT, temozolomide, and enzastaurin post-surgical resection of their tumor. Fewer microbleeds are present in this patient at both 3 and 4 years post-RT compared to the patient in A. D.) Plot of microbleed counts over different time periods showing the retardation of microbleed formation with the administration of an anti-angiogenic agent.

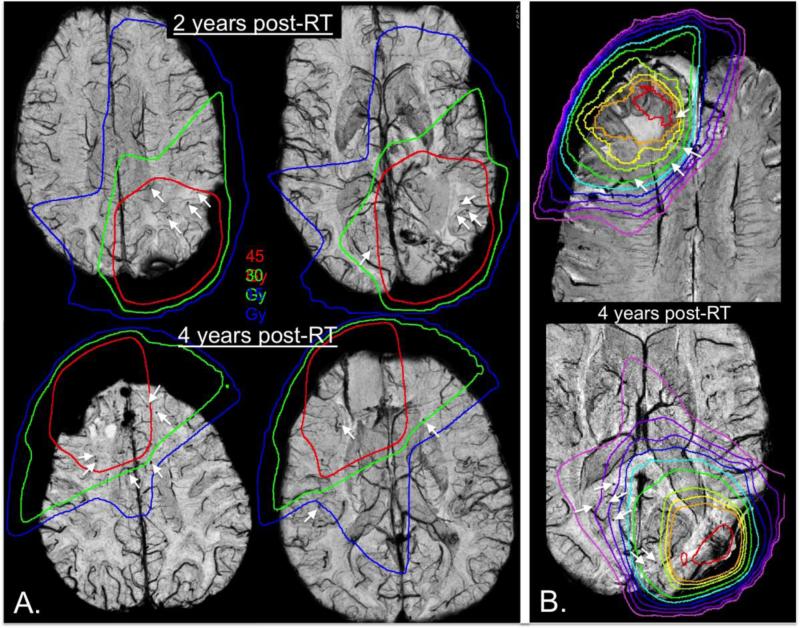

Although in both adult and pediatric populations variations in the number of these lesions have been observed, both across patients and with time, in adults this can most likely be attributed to differences in RT dosimetry administered to normal tissue as shown in Figure 696. As illustrated in Figure 6B, microbleeds often appear outside the T2-hyperintensity lesion and into the contralateral hemisphere after several years when the dosimetry is not well-localized. Even though both patients in Figure 6B have similar microbleed counts, the patient on the bottom panel, where a significant portion of posterior contralateral brain tissue received greater than 15Gy, has microbleeds that extended into the contralateral hemisphere while the patient on the top does not. As depicted in Figure 6A, we have also demonstrated that the appearance of microbleeds is dependent upon the dose of radiation received, with significant increases in microbleed density in higher dose regions and microbleeds forming first in high-dose (ie. after 2 years, top) and later in lower dose regions (ie. after 4 years, bottom). Although we have established that radiation-induced microbleeds can be readily detected and quantified after radiation, the implication of these lesions on brain function and quality of life is still vastly unknown and requires further exploration.

Figure 6.

Microbleed dependence on dose. Radiation dosimetry contour lines overlaid on 7T susceptibility-weighted images. A.) Increases in microbleed density in higher dose regions. At 2 years post-RT (top), more microbleeds form within high-dose regions (red), while by 4 years post-RT (bottom), microbleeds begin to appear in lower dose regions as well (green and blue). B.) Two examples where dose influences microbleed location. When the dosimetry is not well localized (bottom), by 4 years post-RT microbleeds can often appear outside of the T2-hyperintensity lesion and into the contralateral hemisphere. Even though both patients have similar microbleed counts, when a significant portion of posterior contralateral brain tissue received greater than 15Gy dosimetry, microbleeds extended into the contralateral hemisphere.

CONCLUSIONS

Treatment of patients with high grade glioma requires the use of combination treatments that include radiation, temozolomide, and agents targeted to specific biological properties of the lesion. Advanced imaging methods such as perfusion, diffusion, metabolic, and susceptibility weighted imaging can provide metrics to aid in predicting outcome and resolving ambiguities in conventional imaging due to pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse. Elevated values of the choline to N-acetylaspartate index and changes of the values of the apparent diffusion coefficient are indicative of increased tumor cellularity or edema that may represent more reliable measures of response to therapy than changes than the CE or T2 lesion. The combination of susceptibility weighted imaging and automated detection of microbleeds is valuable in assessing the magnitude and spatial distribution of radiation effects in normal brain. It is anticipated that the integration of these advanced imaging methods into a multi-parametric examination that also includes high quality anatomic images would significantly improve the characterization, target definition, assessment of response to therapy, and overall management of patients with high grade glioma.

Grant Acknowledgements

The authors receive support from the following NIH grants R01CA127612, P01CA118816 and P50CA097257.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed R, Oborski MJ, Hwang M, Lieberman FS, Mountz JM. Malignant gliomas: current perspectives in diagnosis, treatment, and early response assessment using advanced quantitative imaging methods. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:149–170. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S54726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhermain F. Radiotherapy of high-grade gliomas: current standards and new concepts, innovations in imaging and radiotherapy, and new therapeutic approaches. Chin J Cancer. 2014;33(1):16–24. doi: 10.5732/cjc.013.10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, et al. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:453–61. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Chalmers L, et al. Early necrosis following concurrent Temodar and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:81–3. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla S, Poptani H, Melhem ER. Anatomic, physiologic and metabolic imaging in neuro-oncology. Cancer Treat Res. 2008;143:3–42. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-75587-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang JH, Kim CY, Choi BS, Kim YJ, Kim JS, Kim IA. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse in the management of high-grade glioma: optimal decision timing according to the response assessment of the neuro-oncology working group. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;55(1):5–11. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2014.55.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY. Novel anti-angiogenic therapies for malignant gliomas. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1152–60. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubenstein J, Kim J, Ozawa T, et al. Anti-VEGF antibody treatment of glioblastoma prolongs survival but results in increased vascular cooption. Neoplasia. 2000;2:306–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF,A, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, DeGroot J, Wick W, Gilbert MR, Lassman AB, Tsien C, Mikkelsen T, Wong ET, Chamberlain MC, Stupp R, Lamborn KR, Vogelbaum MA, van den Bent MJ, Chang SM. Updated Response Assessment Criteria for High-Grade Gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group. J Clin. Oncol. 2010;1028(11):1963–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Susheela SP, Revannasiddaiah S, Madhusudhan N, Bijjawara M. The demonstration of extension of high-grade glioma beyond magnetic resonance imaging defined edema by the use of (11) C-methionine positron emission tomography. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9(4):715–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.126464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosztyla R, Chan EK, Hsu F, Wilson D, Ma R, Cheung A, Zhang S, Moiseenko V, Benard F, Nichol A. High-grade glioma radiation therapy target volumes and patterns of failure obtained from magnetic resonance imaging and 18F-FDOPA positron emission tomography delineations from multiple observers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87(5):1100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieken S, Habermehl D, Giesel FL, Hoffmann C, Burger U, Rief H, Welzel T, Haberkorn U, Debus J, Combs SE. Analysis of FET-PET imaging for target volume definition in patients with gliomas treated with conformal radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109(3):487–92. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellingson BM, Kim HJ, Woodworth DC, Pope WB, Cloughesy JN, Harris RJ, Lai A, Nghiemphu PL, Cloughesy TF. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Bevacizumab: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted Subtraction Maps Improve Tumor Delineation and Aid Prediction of Survival in a Multicenter Clinical Trial. Radiology. 2014;271(1):200–10. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zach L, Guez D, Last D, Daniels D, Grober Y, Nissim O, Hoffmann C, Nass D, Talianski A, Spiegelmann R, Cohen ZR, Mardor Y. Delayed contrast extravasation MRI for depicting tumor and non-tumoral tissues in primary and metastatic brain tumors. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacerda S, Law M. Magnetic resonance perfusion and permeability imaging in brain tumors. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2009 Nov;19(4):527–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dujardin MI, Sourbron SP, Chaskis C, Verellen D, Stadnik T, de Mey J, Luypaert R. Quantification of cerebral tumour blood flow and permeability with T1-weighted dynamic contrast enhanced MRI: a feasibility study. J Neuroradiol. 2012 Oct;39(4):227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barboriak DP, MacFall JR, Viglianti BL, Dewhirst Dvm MW. Comparison of three physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models for the prediction of contrast agent distribution measured by dynamic MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008 Jun;27(6):1388–98. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quarles CC, Gore JC, Xu L, Yankeelov TE. Comparison of dual-echo DSC-MRI- and DCE-MRI-derived contrast agent kinetic parameters. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012 Sep;30(7):944–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludemann L, Warmuth C, Plotkin M, Foschler A, Gutberlet M, Wust P, Amthauer H. Brain tumor perfusion: comparison of dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging using T1, T2, and T2* contrast, pulsed arterial spin labeling, and H2(15)O positron emission tomography. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70(3):465–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boxerman JL, Paulson ES, Prah MA, Schmainda KM. The effect of pulse sequence parameters and contrast agent dose on percentage signal recovery in DSC-MRI: implications for clinical applications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013 Jul;34(7):1364–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boxerman JL, Prah DE, Paulson ES, Machan JT, Bedekar D, Schmainda KM. The Role of preload and leakage correction in gadolinium-based cerebral blood volume estimation determined by comparison with MION as a criterion standard. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012 Jun;33(6):1081–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu LS, Baxter LC, Pinnaduwage DS, Paine TL, Karis JP, Feuerstein BG, Schmainda KM, Dueck AC, Debbins J, Smith KA, Nakaji P, Eschbacher JM, Coons SW, Heiserman JE. Optimized preload leakage-correction methods to improve the diagnostic accuracy of dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging in post-treatment gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010 Jan;31(1):40–8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Essock-Burns E, Phillips JJ, Molinaro AM, Lupo JM, Cha S, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Comparison of DSC-MRI post-processing techniques in predicting microvascular histopathology in patients newly diagnosed with GBM. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;38(2):388–400. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain R, Gutierrez J, Narang J, Scarpace L, Schultz LR, Lemke N, Patel SC, Mikkelsen T, Rock JP. In vivo correlation of tumor blood volume and permeability with histologic and molecular angiogenic markers in gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011 Feb;32(2):388–94. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmainda KM, Prah M, Connelly J, Rand SD, Hoffman RG, Mueller W, Malkin MG. Dynamic-susceptibility contrast agent MRI measures of relative cerebral blood volume predict response to bevacizumab in recurrent high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014 Jan 15; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not216. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haacke EM, Cheng NY, House MJ, Liu Q, Neelavalli J, Ogg RJ, Khan A, Ayaz M, Kirsch W, Obenaus A. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005 Jan;23(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.10.001. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng YC, Reichenbach JR. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI). Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):612–618. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lupo JM, Banerjee S, Hammond KE, Kelley DA, Xu D, Chang SM, Vigneron DB, Majumdar S, Nelson SJ. GRAPPA-based susceptibility-weighted imaging of normal volunteers and patients with brain tumor at 7 T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009 May;27(4):480–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.08.003. Epub 2008 Sep 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Liu M, Bao J, Xia Y, Zhang J, Zhang L, Huang X, Wang J. The correlation between apparent diffusion coefficient and tumor cellularity in patients: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang SM, Nelson SJ, Vandenberg S, Cha S, Prados M, Butowski N, McDermott M, Parsa AT, Aghi M, Clarke J, Berger M. Integration of preoperative anatomic and metabolic physiologic imaging of newly diagnosed glioma. J Neurooncol. 2009;92(3):401–15. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9845-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford FW, Khayal IS, McGue C, Saraswathy S, Pirzkall A, Cha S, Lamborn KR, Chang SM, Berger MS, Nelson SJ. Relationship of pre-surgery metabolic and physiological MR imaging parameters to survival for patients with untreated GBM. J Neurooncol. 2009;91(3):337–51. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9719-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saraswathy S, Crawford FW, Lamborn KR, Pirzkall A, Chang S, Cha S, Nelson SJ. Evaluation of MR markers that predict survival in patients with newly diagnosed GBM prior to adjuvant therapy. J Neurooncol. 2009;91(1):69–81. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9685-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chenevert TL, Stegman LD, Taylor JM, et al. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging: an early surrogate marker of therapeutic efficacy in brain tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(24):2029–2036. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.24.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pope WB, Lai A, Mehta R, Kim HJ, Qiao J, Young JR, Xue X, Goldin J, Brown MS, Nghiemphu PL, Tran A, Cloughesy TF. Apparent diffusion coefficient histogram analysis stratifies progression-free survival in newly diagnosed bevacizumab-treated glioblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011 May;32(5):882–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamstra DA, Galban CJ, Meyer CR, et al. Functional diffusion map as an early imaging biomarker for high-grade glioma: correlation with conventional radiologic response and overall survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3387–3394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain R, Scarpace LM, Ellika S, Torcuator R, Schultz LR, Hearshen D, Mikkelsen T. Imaging response criteria for recurrent gliomas treated with bevacizumab: role of diffusion weighted imaging as an imaging biomarker. J Neurooncol. 2010 Feb;96(3):423–31. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9981-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galban CJ, Chenevert TL, Meyer CR, Tsien C, Lawrence TS, Hamstra DA, Junck L, Sundgren PC, Johnson TD, Galbάn S, Sebolt-Leopold JS, Rehemtulla A, Ross BD. Prospective analysis of parametric response map-derived MRI biomarkers: identification of early and distinct glioma response patterns not predicted by standard radiographic assessment. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Jul 15;17(14):4751–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khayal IS, Polley MY, Jalbert L, Elkhaled A, Chang SM, Cha S, Butowski NA, Nelson SJ. Evaluation of diffusion parameters as early biomarkers of disease progression in glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(9):908–16. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellingson BM, Cloughesy TF, Lai A, Nghiemphu PL, Pope WB. Cell invasion, motility, and proliferation level estimate (CIMPLE) maps derived from serial diffusion MR images in recurrent glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(1):91–101. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellingson BM, Cloughesy TF, Lai A, Mischel PS, Nghiemphu PL, Lalezari S, Schmainda KM, Pope WB. Graded functional diffusion map-defined characteristics of apparent diffusion coefficients predict overall survival in recurrent glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(10):1151–61. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berman JI, Berger MS, Chung SW, Nagarajan SS, Henry RG. Accuracy of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging tractography assessed using intraoperative subcortical stimulation mapping and magnetic source imaging. J Neurosurg. 2007 Sep;107(3):488–94. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/09/0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wedeen VJ, Hagmann P, Tseng WY, Reese TG, Weisskoff RM. Mapping complex tissue architecture with diffusion spectrum magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(6):1377–86. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Schneider T, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Alexander DC. NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):1000–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoff BA, Chenevert TL, Bhojani MS, Kwee TC, Rehemtulla A, Le Bihan D, Ross Galban CJ. Assessment of multiexponential diffusion features as MRI cancer therapy response metrics. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(5):1499–509. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson SJ. Assessment of therapeutic response and treatment planning for brain tumors using metabolic and physiological MRI. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(6):734–49. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozhinsky E, Vigneron DB, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Automated Prescription of Oblique Brain 3D Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(4):920–30. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKnight TR, von dem Bussche MH, Vigneron DB, Lu Y, Berger MS, McDermott MW, Dillon WP, Graves EE, Pirzkall A, Nelson SJ. Histopathological validation of a three-dimensional magnetic resonance spectroscopy index as a predictor of tumor presence. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(4):794–802. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.4.0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo J, Yao C, Chen H, Zhuang D, Tang W, Ren G, Wang Y, Wu J, Huang F, Zhou L. The relationship between Cho/NAA and glioma metabolism: implementation for margin delineation of cerebral gliomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154(8):1361–70. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKnight TR, Noworolski SM, Vigneron DB, Nelson SJ. An automated technique for the quantitative assessment of 3D-MRSI data from patients with glioma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001 Feb;13(2):167–77. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200102)13:2<167::aid-jmri1026>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barajas RF, Jr, Phillips JJ, Parvataneni R, Molinaro A, Essock-Burns E, Bourne G, Parsa AT, Aghi MK, McDermott MW, Berger MS, Cha S, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Regional Variation in Histopathological Features of Tumor Specimens from Treatment-Naive Glioblastoma Correlates with Anatomic and Physiologic MR Imaging. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(7):942–54. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jain R, Narang J, Gutierrez J, Schultz LR, Scarpace L, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T, Rock JP. Correlation of immunohistologic and perfusion vascular parameters with MR contrast enhancement using image-guided biopsy specimens in gliomas. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(8):955–62. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu LS, Eschbacher JM, Dueck AC, Heiserman JE, Liu S, Karis JP, Smith KA, Shapiro WR, Pinnaduwage DS, Coons SW, Nakaji P, Debbins J, Feuerstein BG, Baxter LC. Correlations between perfusion MR imaging cerebral blood volume, microvessel quantification, and clinical outcome using stereotactic analysis in recurrent high-grade glioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(1):69–76. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pirzkall A, McKnight TR, Graves EE, Carol MP, Sneed PK, Wara WW, Nelson SJ, Verhey LJ, Larson DA. MR-spectroscopy guided target delineation for high-grade Gliomas. Int J Radiation Oncol, Biol, Physics. 2001;50(4):915–928. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pirzkall X, Li J, Oh S, Chang MS, Berger MW, McDermott DA, Larson LJ, Verhey WP, Dillon, Nelson SJ. 3D MR-Spectroscopy for resected high-grade Gliomas prior to RT: tumor extent according to metabolic activity in relation to MRI”. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol, Phys. 2004;159(1):126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nelson SJ, Graves E, Pirzkall A, Li X, Chan AA, Vigneron D, McKnight TR. In vivo molecular imaging for planning radiation therapy of Gliomas: an application of 1H MRSI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2002;16:464–476. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Graves EE, Pirzkall A, McKnight TR, Vigneron DB, Larson DA, Verhey LJ, McDermott M, Chang S, Nelson SJ. Use of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging data for planning focal radiation therapies. Image Analysis & Stereology. 2002;21:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ken S, Vieillevigne L, Franceries X, Simon L, Supper C, Lotterie JA, Filleron T, Lubrano V, Berry I, Cassol E, Delannes M, Celsis P, Cohen-Jonathan EM, Laprie A. Integration method of 3D MR spectroscopy into treatment planning system for glioblastoma IMRT dose painting with integrated simultaneous boost. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-1. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith JS1, Cha S, Mayo MC, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Chang SM, Dillon WP, Berger MS. Serial diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in cases of glioma: distinguishing tumor recurrence from post-resection injury. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(3):428–38. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.3.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pirzkall A, McGue C, Saraswathy S, Cha S, Liu R, Vandenberg S, Lamborn KR, Berger MS, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Tumor regrowth between surgery and initiation of adjuvant therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(6):842–52. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graves EE, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Verhey L, McDermott M, Larson D, Chang S, Prados MD, Dillon WP. Serial proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of recurrent malignant Gliomas after gamma knife radio surgery. Am. J. Neuro-Radiology. 2001;22:613–624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan AA, Lau A, Pirzkall A, Chang SM, Verhey LJ, Larson D, McDermott M, Dillon W, Nelson SJ. Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging as a tool for evaluating grade IV Glioma patients undergoing gamma knife radio surgery. J. Neurosurgery. 2004;101(3):467–475. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.3.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chuang CF, Chan AA, Larson D, Verhey LJ, McDermott M, Nelson SJ, Pirzkall A. Potential value of MR spectroscopic imaging for the radiosurgical management of patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2007;6(5):375–82. doi: 10.1177/153303460700600502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lemasson B, Chenevert TL, Lawrence TS, Tsien C, Sundgren PC, Meyer CR, Junck L, Boes J, Galbán S, Johnson TD, Rehemtulla A, Ross BD, Galbán CJ. Impact of perfusion map analysis on early survival prediction accuracy in glioma patients. Transl Oncol. 2013;6(6):766–74. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Essock-Burns E, Lupo JM, Cha S, Polley MY, Butowski NA, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Assessment of perfusion MRI-derived parameters in evaluating and predicting response to antiangiogenic therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(1):119–31. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mangla R, Singh G, Ziegelitz D, Milano MT, Korones DN, Zhong J, Ekholm SE. Changes in relative cerebral blood volume 1 month after radiation-temozolomide therapy can help predict overall survival in patients with glioblastoma. Radiology. 2010 Aug;256(2):575–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091440. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091440. Epub 2010 Jun 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karis JP, Smith KA, Coons SW, Nakaji P, Spetzler RF, Feuerstein BG, Debbins J, Baxter LC. Reevaluating the imaging definition of tumor progression: perfusion MRI quantifies recurrent glioblastoma tumor fraction, pseudoprogression, and radiation necrosis to predict survival. Neuro Oncol. 2012 Jul;14(7):919–30. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Young RJ, Gupta A, Shah AD, Graber JJ, Chan TA, Zhang Z, Shi W, Beal K, Omuro AM. MRI perfusion in determining pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma. Clin Imaging. 2013 Jan-Feb;37(1):41–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Y, Lupo JM, Polley MY, Crane JC, Bian W, Cha S, Chang S, Nelson SJ. Serial analysis of imaging parameters in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2011 May;13(5):546–57. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Y, Lupo JM, Parvataneni R, Lamborn KR, Cha S, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Survival analysis in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma using pre-and post-radiotherapy MR spectroscopic imaging. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(5):607–17. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tran DK, Jensen RL. Treatment-related brain tumor imaging changes: So-called “pseudoprogression” vs. tumor progression: Review and future research opportunities. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 3):S129–35. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.110661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barajas RF, Jr, Chang JS, Segal MR, Parsa AT, McDermott MW, Berger MS, Cha S. Differentiation of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme from radiation necrosis after external beam radiation therapy with dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;253(2):486–96. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hu LS, Baxter LC, Smith KA, Feuerstein BG, Karis JP, Eschbacher JM, Coons SW, Nakaji P, Yeh RF, Debbins J, Heiserman JE. Relative cerebral blood volume values to differentiate high-grade glioma recurrence from post-treatment radiation effect: direct correlation between image-guided tissue histopathology and localized dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging measurements. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(3):552–8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu JL, Shi DP, Dou SW, Li YL, Yan FS. Distinction between postoperative recurrent glioma and delayed radiation injury using MR perfusion weighted imaging. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55(6):587–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fatterpekar GM, Galheigo D, Narayana A, Johnson G, Knopp E. Treatment-related change versus tumor recurrence in high-grade gliomas: a diagnostic conundrum--use of dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced (DSC) perfusion MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(1):19–26. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7417. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7417. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shin KE, Ahn KJ, Choi HS, Jung SL, Kim BS, Jeon SS, Hong YG. DCE and DSC MR perfusion imaging in the differentiation of recurrent tumour from treatment-related changes in patients with glioma. Clin Radiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.01.016. pii:S0009-9260(14)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fink JR, Carr RB, Matsusue E, Iyer RS, Rockhill JK, Haynor DR, Maravilla KR. Comparison of 3 Tesla proton MR spectroscopy, MR perfusion and MR diffusion for distinguishing glioma recurrence from post-treatment effects. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(1):56–63. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim YH, Oh SW, Lim YJ, Park CK, Lee SH, Kang KW, Jung HW, Chang KH. Differentiating radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence in high-grade gliomas: assessing the efficacy of 18F-FDG PET, 11C-methionine PET and perfusion MRI. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(9):758–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Di Costanzo A, Scarabino T, Trojsi F, Popolizio T, Bonavita S, de Cristofaro M, Conforti R, Cristofano A, Colonnese C, Salvolini U, Tedeschi G. Recurrent glioblastoma multiforme versus radiation injury: a multiparametric 3-T MR approach. Radiol Med. 2014 Jan 10; doi: 10.1007/s11547-013-0371-y. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sundgren PC1, Fan X, Weybright P, Welsh RC, Carlos RC, Petrou M, McKeever PE, Chenevert TL. Differentiation of recurrent brain tumor versus radiation injury using diffusion tensor imaging in patients with new contrast-enhancing lesions. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006 Nov;24(9):1131–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.07.008. Epub 2006 Sep 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hein PA1, Eskey CJ, Dunn JF, Hug EB. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the follow-up of treated high-grade gliomas: tumor recurrence versus radiation injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004 Feb;25(2):201–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Al Sayyari A1, Buckley R, McHenery C, Pannek K, Coulthard A, Rose S. Distinguishing recurrent primary brain tumor from radiation injury: a preliminary study using a susceptibility-weighted MR imaging-guided apparent diffusion coefficient analysis strategy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(6):1049–54. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lupo JM, Essock-Burns E, Molinaro AM, Cha S, Chang SM, Butowski N, Nelson SJ. Using susceptibility-weighted imaging to determine response to combined anti-angiogenic, cytotoxic, and radiation therapy in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(4):480–9. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Valk PE, Dillon WP. Radiation injury of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12(1):45–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jain R, Robertson PL, Gandhi D, et al. Radiation-induced cavernomas of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1158e1162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee MC, Cha S, Chang SM, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion imaging of radiation effects in normal-appearing brain tissue: Changes in the first-pass and recirculation phases. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21:683e693. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang YX, King AD, Zhou H, et al. Evolution of radiation-induced brain injury: MR imaging-based study. Radiology. 2010;254:210e218. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nagesh V, Tsien CI, Chenevert TL, et al. Radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing white matter in patients with cerebral tumors: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1002e1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Welzel T, Niethammer A, Mende U, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging screening of radiation-induced changes in the white matter after prophy-lactic cranial irradiation of patients with small cell lung cancer: First results of a prospective study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:379e383. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lupo JM, Chuang CF, Chang SM, Barani IJ, Hess CP, Nelson SJ. 7 Tesla Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging to Assess the Effects of Radiation Therapy on Normal Appearing Brain in Patients with Glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(3):e493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fajardo LF. The pathology of ionizing radiation as defined by morphologic patterns. Acta Oncol. 2005;44(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/02841860510007440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fazekas F, Kleinert R, Roob G, Kleinert G, Kapeller P, Schmidt R, Hartung HP. Histopathologic analysis of foci of signal loss on gradient-echo T2*-weighted MR images in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: evidence of microangiopathy-related microbleeds. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(4):637–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peters S, Pahl R, Claviez A, Jansen O. Detection of irreversible changes in susceptibility-weighted images after whole-brain irradiation of children. Neuroradiology. 2013;55(7):853–9. doi: 10.1007/s00234-013-1185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lupo JM, Anwar M, Hess CP, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Relating Radiation Dose to Microbleed Formation in Patients with Glioma.. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Melbourne. 2012; abstract 186. [Google Scholar]