Abstract

Background

The antimanic efficacy of a protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor, tamoxifen, has been tested in several clinical trials, all reporting positive results. However, mechanisms underlying the observed clinical effects requires further confirmation through studies of biological markers.

Methods

We investigated the effect of tamoxifen versus placebo on brain metabolites via a proton (1H) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) study. Forty-eight adult bipolar I manic patients (mean Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score of 37.8±5.8) were scanned at baseline and following 3 weeks of double-blind treatment. We hypothesized that manic symptom alleviation would improve the levels of markers associated with brain energy metabolism (creatine plus phosphocreatine [total creatine; tCr]) and neuronal viability (N-acetylaspartate [NAA]).

Results

The YMRS scores decreased from 38.6±4.5 to 20.0±11.1 in the tamoxifen group and increased from 37.0±6.8 to 43.1±7.8 in the placebo group (p<0.001). 1H MRS measurements revealed a 5.5±13.8% increase in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC) tCr levels in the tamoxifen group and a 5.3±13.1% decrease in tCr in the placebo group (p=0.027). A significant correlation between the YMRS score change and tCr percent change was observed in the whole group (Spearman ρ=0.341, p=0.029). Both tCr and NAA levels in the responder group were increased by 9.4±15.2% and 6.1±11.7%, whereas levels in the non-responder group were decreased by 2.1±13.2% and 6.5±10.5%, respectively (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Tamoxifen effectively treated mania while it also increased brain tCr levels, consistent with involvement of both excessive PKC activation and impaired brain energy metabolism in the development of bipolar mania.

Clinical trial registration

Registry name: ClinicalTrials.gov

URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00411203?term=NCT00411203&rank=1

Registration number: NCT00411203

Keywords: Tamoxifen, protein kinase C, MRS, bipolar mania, creatine, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) has been associated with a wide range of neurobiological models, but pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the extreme and erratic shifts of mood, thinking, and behavior associated with this complex disorder are yet to be fully elucidated. Nevertheless, in the light of accumulated evidence, a few hypotheses are supported by convergent and replicated evidence. Among these are mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage resulting in altered brain energy metabolism (1), altered arachidonic acid cascade and inflammatory response (2), decreased neuroplasticity (3), and increased protein kinase C (PKC) activation (4). The extent to which these brain processes take part or interact with each other in the development of bipolar mood states will require further research (1, 3–6).

Evidence from different types of studies suggests that excessive PKC activation can disrupt prefrontal cortical regulation of thinking and behavior (7, 8) and use of PKC inhibitors such as tamoxifen can improve mania-like symptoms (i.e. amphetamineinduced hyperactivity) in animal models (5, 9–13). The results from genetic, postmortem, and clinical investigations also support a role for altered PKC signaling in the pathophysiology and treatment of BD (5, 13). A polymorphism in the gene encoding phospholipase C, the initial enzyme in the PKC cascade, was identified in a population-based association study of BD patients who were responders to lithium (14). A genome-wide association study of BD in two independent case-control samples of European origin found the strongest association signal in the gene encoding deacylglycerol kinase eta, a key protein for the PKC pathway (5, 15). While postmortem findings show increased PKC activity in the frontal cortex of patients with BD (16), bipolar manic patients have accelerated membrane-bound PKC activity in their platelets and treatment with lithium or valproate normalized this abnormal activity within two weeks (5, 13, 17). A few proof-of-concept trials employing tamoxifen as the study drug have further investigated the role of PKC inhibition in the treatment of acute mania (13, 18–20), all reporting positive results with a rapid onset of action (within 5 days) and response rates for tamoxifen up to 63% after 3 weeks of treatment (5).

Mitochondrial pathology has been repeatedly shown to accompany BD and been considered to result from genetic and environmental causes, as well as neurotransmission dysregulation (21). Through structural abnormalities (22) and inefficient energy production and oxidative stress (23), mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to BD pathophysiology, as evidenced by increased neuronal lactate (24) and decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA) (25), creatine plus phosphocreatine (total creatine; tCr) (26), and pH levels (27) detected in BD patients by several cerebral magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies.

Proof-of-concept clinical trials are based on etiologic molecular models and they are valuable for developing new target-specific treatments. However, proposed drug mechanisms of action require further confirmation through studies of biological markers in the actual study populations. MRS is a noninvasive neuroimaging tool enabling investigation of in vivo neurochemistry. Proton (1H) MRS is most commonly used in clinical research settings and it can provide information on the levels of (i) NAA, a marker synthesized in the mitochondria and considered to reflect neuronal density, viability, and function; (ii) phosphorylcholine plus glycerophospocholine (Cho), which participate in membrane phospholipid turnover; and (iii) tCr, which is involved in brain energy metabolism and can be used to store high energy phosphate bonds used to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (1, 28).

By adding a longitidunal 1H MRS study to the largest randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, antimanic treatment trial of a PKC inhibitor, tamoxifen, we investigated neurochemical changes in the bipolar manic state before and following 3 weeks of treatment by tamoxifen. Based on the above-mentioned molecular mechanisms, we hypothesized a priori that manic symptom amelioration via treatment with tamoxifen would improve brain energy metabolism (reflected in increased tCr levels) and neuronal viability (reflected in increased NAA levels).

Methods and Materials

Subjects

This longitidunal 1H MRS study was added to a proof-of-concept study of tamoxifen designed for testing the antimanic efficacy of PKC inhibition (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00411203). The full protocol and results of this trial were previously reported (13). Briefly, patients were aged 18 to 58 years old, diagnosed as having DSM-IV type I BD currently in a manic or mixed state with a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score greater than 20, with or without psychotic features. The Turkish Ministry of Health Central Review Board and the Local Ethical Committee of Dokuz Eylul University approved the study protocol. Each potential subject and one first-degree relative reviewed the study and both gave written informed consent for participation.

Treatment and clinical assessment

Subjects were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive tamoxifen citrate or identical placebo tablets in a double-blind fashion for 3 weeks. The starting dosage of tamoxifen citrate was 20 mg twice daily (40 mg/day). Daily doses were adjusted gradually in 10 mg increments to achieve 80 mg/day in twice-daily divided doses for all subjects. Concomitant use of oral lorazepam was allowed during the study as clinically indicated, with a maximum dose of 5 mg/day. All subjects were hospitalized throughout the 3 week trial period and beyond until adequate manic symptom amelioration could be achieved. Manic symptom severity was evaluated using the YMRS, completed weekly over the 3 week period.

MRS procedure and data analysis

The present 1H MRS study protocol was a part of longitudinal 1H MRS studies added to two clinical trials, one for bipolar mania (13), and the other for unipolar depression (29). The clinical trials and 1H MRS experiments were conducted at the Dokuz Eylul University, Departments of Psychiatry and Radiology, Izmir, Turkey. The Local Ethical Committee of Dokuz Eylul University approved the 1H MRS study protocol. In this project, baseline 1H MR spectra from the bipolar manic patients were obtained right before randomization to tamoxifen or placebo. Following 3 weeks of a double-blind treatment period, 1H MR spectra were obtained again (within 12 hours after the last dose of treatment with no concomitant psychotropic medication administered). For enabling reliable data acquisition in the manic state, all patients were sedated with midazolam (0.03 mg/kg) and fentanyl (2 µg/kg) administration just before both MR scans (28). As reported previously, the chemical sedation was found safe and did not cause any alterations in the measured metabolites of the brain (28). 1H MRS measurements were made on a Philips System MR scanner with field strength of 1.5 Tesla. Sagittal, axial, and coronal T2-weighted cerebral images were obtained to place voxels and single voxel short TE MRS data were collected with a PRESS sequence (TE=31 ms, TR=2000 ms, spectral bandwidth 1 kHz, 1024 complex data points, 128 acquisitions), from four different brain regions: dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), right basal ganglia, frontal lobe, and right hippocampus in order to create a database for present and future comparisons in mood disorder patients and healthy volunteers. For the present report, we selected DMPFC as our primary region of interest, since it covers the regions most prominently shown to be involved in BD (30–32). The DMPFC voxel dimensions were 2 × 3 × 2.5 cm (15 cm3) (Figure 1). Specifically trained, blinded experts at the study site made data acquisitions and metabolite measurements.

Figure 1. Voxel placement (2 × 3 × 2.5 cm3) of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in axial (A), sagittal (B), and coronal (C) magnetic resonance images.

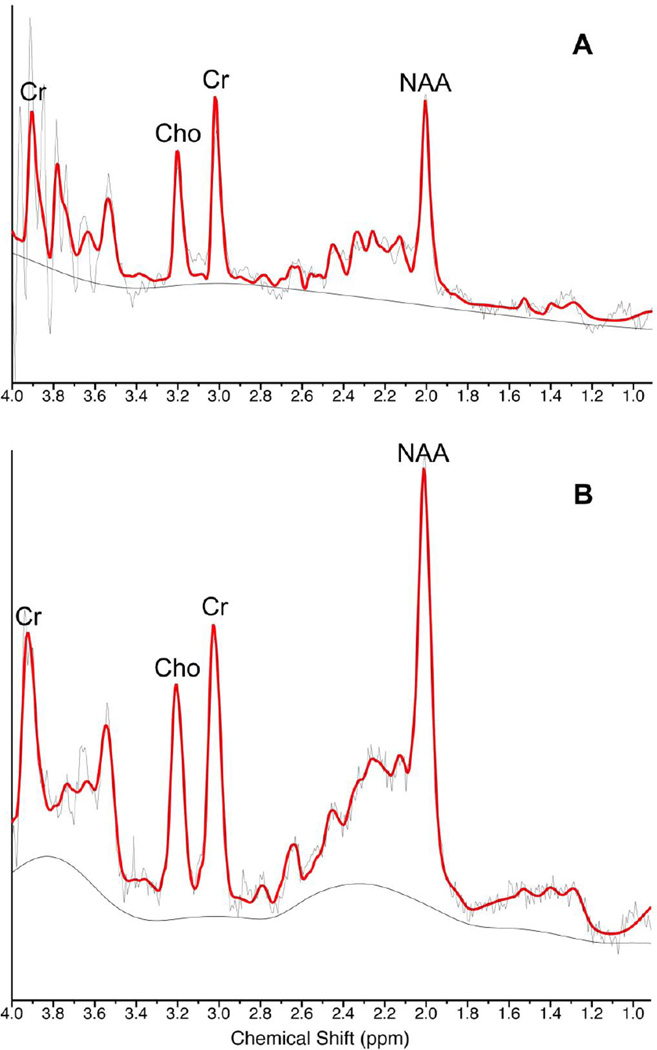

Unsuppressed water reference spectra were acquired for all acquisitions and used for both eddy-current correction and water-scaling to estimate absolute metabolite concentrations. The commercial spectral-fitting package LC Model (version 6.1-4E) was used to measure individual metabolite peak integrals (28, 33). To accept individual metabolite fitting, we set Cramer-Rao lower bounds (CRLB) threshold of less than 20% for NAA, Cho, and tCr. Of the 96 MR spectra (baseline and end-trial spectra for 48 patients) obtained, five were excluded due to low spectral resolution. CRLBs for each metabolite fitting are presented in Table S1 in Supplement 1. In the present study, metabolite levels were measured in institutional units. Sample magnetic resonance spectra are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sample magnetic resonance spectra of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex of the same patient (A) at baseline and (B) after tamoxifen treatment for 3 weeks.

Red line, modeled spectrum. NAA=N-acetylaspartate. Cr=creatine+phosphocreatine. Cho=phosphorylcholine+glycerophospocholine. Chemical shift in parts-per-million (ppm).

Statistics

For the demographic and clinical characteristics, continuous data were expressed as mean±SD and analyzed with Student's t-test, whereas categorical data were expressed with frequencies and analysed with Pearson's chi-squared test. As the data for metabolite levels and percentage changes were nonparametric and the sample sizes were small, data were presented both as mean±SD and median and range. Metabolite baseline levels and percentage changes were compared between the groups via the Mann–Whitney U test. To further examine the baseline tCr level difference observed between treatment groups, two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, as the assumption of normality was fulfilled, to assess the main effects of group (tamoxifen and placebo), time (baseline and end-trial), and group × time interaction on tCr levels. Associations between the YMRS score changes and metabolite percentage changes were explored by linear regression analysis and Spearman's rank correlation. Discriminating values of the metabolite changes for response were evaluated with the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. An optimal cut-off point was selected for the targeted metabolite changes, which was found to be statistically significant according to the area under the curve (AUC) computations. Sensitivity and specificity of the selected cut-off point was further evaluated. A two-sided p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 20; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) software.

Results

A total of 48 patients, randomized to tamoxifen (n=25) or placebo (n=23), participated in the study. All patients completed the 3 week trial. Tamoxifen and placebo groups were well matched at baseline for demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in Tamoxifen and Placebo Groups

| Characteristic | Tamoxifen (n=25) |

Placebo (n=23) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | |||

| At randomization | 32.8 (13.5) | 36.1 (13.0) | 0.402a |

| At onset of illness | 23.2 (8.2) | 27.2 (9.2) | 0.126a |

| Gender (Female/Male), No. | 13/12 | 11/12 | 0.773b |

| Handedness (Right/Left), No. | 20/5 | 21/2 | 0.268b |

| First episode, No. | 0.117b | ||

| Manic | 13 | 17 | |

| Depressive | 12 | 6 | |

| History of psychosis (Yes/No), No. | 18/7 | 19/4 | 0.382b |

| Family history, No. | 0.455b | ||

| No psychiatric disorder | 3 | 6 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 18 | 12 | |

| Unipolar depression | 2 | 3 | |

| Schizophrenia | 0 | 1 | |

| Alcohol and substance abuse | 2 | 1 | |

| Lorazepam used (Yes/No), No. | 20/5 | 20/3 | 0.518b |

| Baseline YMRS, Mean (SD) | 38.6 (4.5) | 37.0 (6.8) | 0.353a |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), Mean (SD) | 24.9 (5.4) | 25.0 (4.4) | 0.945a |

| Active smoking status (Yes/No), No. | 11/14 | 10/13 | 0.971b |

| Active comorbidity, No. | 0.417b | ||

| None | 20 | 17 | |

| Endocrine disorders | 3 | 1 | |

| Hematological disorders | 1 | 0 | |

| Circulatory system disorders | 1 | 0 | |

| Eye disorders | 0 | 1 | |

| Skin disorders | 0 | 1 | |

| Allergy | 0 | 1 | |

| Musculoskeletal system disorders | 0 | 1 | |

| Ear disorders | 0 | 1 | |

| Medication use in the last four weeks, No.c | |||

| Antidepressants | 5 | 5 | 0.882b |

| First-generation antipsychotics | 7 | 3 | 0.116b |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | 8 | 10 | 0.709b |

| Lithium | 8 | 10 | 0.709b |

| Anticonvulsants | 1 | 6 | 0.054b |

| Other medications for comorbidities | 4 | 2 | 0.326b |

YMRS=Young mania rating scale.

For Student's t test.

For Pearson's chi-squared test.

Some patients used more than one medication in the last four weeks.

Mania ratings indicated significant YMRS score reductions with tamoxifen (ΔYMRS= −18.5±9.4), and worsening with placebo (ΔYMRS= 6.1±7.9) after completion of 3 weeks study period (p<0.001). Rates of response (patients with ≥50% reduction in the YMRS scores from baseline to study completion at 3 weeks) were 44% (11 of 25) with tamoxifen vs. none (0 of 23) with placebo treatment (p<0.001). Mean ages of responders and non-responders were 31.5±13.8 and 35.3±13.1, respectively (p=0.407). Responders and non-responders had similar baseline YMRS scores (38.0±4.5 vs. 37.8±6.1; p=0.904).

Metabolite levels of the treatment groups at baseline are presented in Table S2 in Supplement 1. Baseline mean tCr levels in DMPFC were lower in the tamoxifen group (4.64±0.59) when compared to the placebo group (5.34±0.58; p=0.001) while other metabolite levels were similar among the treatment groups. Percent metabolite changes in the DMPFC from baseline to the end of 3 weeks trial period per treatment group are illustrated in Table 2. 1H MRS measurements revealed a 5.5±13.8% increase in tCr levels with tamoxifen and a 5.3±13.1% decrease with placebo treatment (p=0.027). All other metabolite changes were similar between the groups (Table 2). For tCr levels, there were significant main effects of group [F(1,39)=8.257, p=0.007] and group × time interaction [F(1,39)=6.011, p=0.019] but no main effect of time [F(1,39)=0.291, p=0.593]. Linear regression analysis demonstrated a significant association between the YMRS score changes and tCr percent changes in the tamoxifen group (Pearson R2=0.178, p=0.045), but not in the placebo group (p=0.465) whereas Spearman's rank correlation analysis for YMRS score changes and tCr percent changes yielded insignificant results (p=0.094 for tamoxifen group; p=0.181 for placebo group). Whole group (n=41) analyses showed significant associations between the YMRS score changes and tCr percent changes (Pearson R2=0.169, p=0.008; Spearman ρ=0.341, p=0.029). The direction of significant associations indicated that a decrease in manic symptom severity was significantly correlated with higher tCr levels. Scatter plots of YMRS score changes and tCr and NAA percent changes are presented in Figure S1 in Supplement 1. No significant association was found between YMRS score changes and NAA or Cho percent changes or baseline tCr levels and YMRS score changes in either group.

Table 2.

Percent changes of metabolite levels in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex after completion of 3-weeks trial period per treatment group

| Tamoxifen | Placebo |

P valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean±SD | Median (min;max) | n | Mean±SD | Median (min;max) | ||

| NAA | 23 | −0.7±12.7 | −0.7 (−23.2;26.5) | 17 | −6.9±10.1 | −7.2 (−21.0;15.4) | 0.122 |

| tCr | 23 | 5.5±13.8 | 7.7 (−21.9;31.2) | 18 | −5.3±13.1 | −5.2 (−28.5;18.9) | 0.027 |

| Cho | 20 | 9.6±16.4 | 6.6 (−33.5;42.9) | 17 | 3.9±24.3 | 6.0 (−37.3;45.4) | 0.478 |

NAA=N-acetylaspartate. tCr=creatine+phosphocreatine. Cho=phosphorylcholine+glycerophospocholine.

For Mann-Whitney U test.

When all the study participants were categorized according to response irrespective of the treatment arm, baseline metabolite levels were similar among the response groups (Table S3 in Supplement 1). After the trial period, both tCr and NAA levels in the responders group were increased by 9.4±15.2% and 6.1±11.7%, whereas levels in the non-responders group were decreased by 2.1±13.2% and 6.5±10.5%, respectively, in the DMPFC. Both differences between the responders and non-responders were deemed as significant (p<0.05; Table 3). ROC analysis showed that percent changes of tCr and NAA levels in the DMPFC distinguished non-responders from the responders with sensitivities of 70% and 70%, and specificities of 61% and 67%, respectively (Table 4).

Table 3.

Percent changes of metabolite levels in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex after completion of 3-weeks trial period per response

| Responder | Non-responder |

P valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean±SD | Median (min;max) | n | Mean±SD | Median (min;max) | ||

| NAA | 10 | 6.1±11.7 | 4.3 (−8.5;26.5) | 30 | −6.5±10.5 | −6.8 (−23.2;15.4) | 0.009 |

| tCr | 10 | 9.4±15.2 | 9.6 (−14.7;31.2) | 31 | −2.1±13.2 | −0.6 (−28.5;25.9) | 0.039 |

| Cho | 7 | 8.7±10.0 | 5.8 (−0.5;22.9) | 30 | 6.6±22.2 | 6.3 (−37.3;45.4) | 0.925 |

NAA=N-acetylaspartate. tCr=creatine+phosphocreatine. Cho=phosphorylcholine+glycerophospocholine.

For Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis results for differentiating non-responders from responders with metabolite percent changes after completion of 3-weeks trial period

| AUC | Standard Error | P value | Cutoff point for metabolite % change |

Sensitivity- Specificitya |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA | 0.773 | 0.082 | 0.010 | −1.4 | 0.70-0.67 |

| tCr | 0.719 | 0.096 | 0.039 | +4.1 | 0.70-0.61 |

| Cho | 0.514 | 0.095 | 0.907 | NA | NA |

NAA=N-acetylaspartate. tCr=creatine+phosphocreatine. Cho=phosphorylcholine+glycerophospocholine. AUC=area under the curve. NA=not applicable.

Optimal values.

Discussion

While best known for its antiestrogen properties, tamoxifen is also a potent PKC inhibitor and its antimanic efficacy has been consistently detected in several proof-of-concept trials (13, 18–20, 34). A subsample from the largest of these trials is the subject of the present report (13), which revealed that successful antimanic treatment via a PKC inhibitor increased tCr levels in bipolar manic patients in a brain region associated with regulation of mood and behavior, namely DMPFC. More specifically, bipolar manic patients treated with tamoxifen demonstrated a significant increase in their DMPFC tCr levels, while no such change was observed in the group treated with placebo. Furthermore, the increase in tCr levels in the DMPFC was correlated with lowered YMRS scores. When the study participants were categorized according to clinical response, further evidence for improved energy metabolism as a concomitant of clinical improvement was obtained. Specifically, responders at 3 weeks had significantly increased tCr and NAA levels while non-responders had significantly lower tCr and NAA levels in the DMPFC. To assess the possibility that such an association between the DMPFC tCr and NAA levels and antimanic treatment responses occurred simply by chance, observed associations were further tested via ROC analysis. These analyses confirmed that the increase in tCr and NAA levels in the DMPFC could differentiate non-responders from responders, albeit with moderate sensitivity and specificity. A similar finding indicating increased ventral prefrontal NAA levels, but not tCr levels, in bipolar manic state remitters to olanzapine treatment has previously been reported (35).

Alteration in the brain energy metabolism resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction is among the most plausible models associated with BD (5, 21, 36). Through the electron transport chain, mitochondria regulate energy production in the cell, and their dysfunction can result in a compromise of neuronal function via decreased ATP production. This is due to anaerobic, rather than aerobic pathways, oxidative damage, abnormal calcium sequestration, and apoptosis via activation of caspase proteases (5, 6, 23). Inappropriate use of anaerobic pathways leads to insufficient energy supply, which may be reflected in terms of decreased tCr levels in the brain (26), along with generation of excessive lactate and reactive oxygen species, both leading to decreased cellular pH levels as demonstrated in previous 1H MRS studies (24, 27). In addition to the mitochondrial dysfunction, a decreased phosphocreatine/ATP ratio and an impaired ability to use phosphocreatine to replenish ATP production have also been reported in BD patients by using 31P MRS, thus further supporting the evidence of abnormal brain energy metabolism in BD (37).

Another sign of compromised energy production is decreased levels of NAA seen in BD patients compared to normal controls (25). Since NAA originates in mitochondria and is a marker of neuronal viability, as well as brain energy metabolism, its reduction may well be mechanistically related to decreased tCr levels associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (5). Therefore, our findings of lower tCr levels during the bipolar manic state and an increase in response to successful antimanic treatment support the ability of both tCr and NAA levels to differentiate antimanic treatment responders from nonresponders. These findings also support the role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in mediating the bipolar manic state and its treatment. Animal studies had previously indicated that PKC inhibition by tamoxifen (38, 39) might modulate and correct mitochondrial energy metabolism, oxidative stress, as well as creatine kinase inhibition (5). However, our study is the first to establish an interaction between these two mechanisms for the etiological basis of BD; mitochondrial dysfunction and alteration in the PKC signaling pathway in humans. The dual effects of tamoxifen, in terms of symptomatically treating mania and improving brain energy metabolism, implicates the involvement of both excessive PKC activation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of bipolar mania. The antiestrogenic activity of tamoxifen might have also contributed to its antimanic and metabolic effects, yet this possibility needs further investigation (40).

The present 1H MRS study was carried out in association with clinical assessments in a randomized, controlled trial setting. Strengths were the non-industrial source of funding, proof-of-concept design, and presence of severely manic patients who were minimally contaminated by medication effects. All of these features are relatively unique for this type of 1H MRS experiments. In addition, the symptomatic status of study participants was concurrently evaluated with their brain chemistry, both in a double-blind manner. We believe manic symptom severity in the study population might have contributed the neurochemical signal related with the disease state as well as its treatment (41, 42). Optimization of the spectral data acquisition via restricted head motion might have further contributed to the detection of the anticipated spectral signal (28).

Our study also had several limitations. We performed the MRS experiments at a 1.5 T magnetic field strength. Studies with higher field strengths could increase the resolution and sensitivity for voxel placement as well as spectral acquisition (43). The sample size was modest and it is likely that the small sample size together with the low field strength might have caused some other potential neurochemical alterations to be unnoticed. As we performed the comparative analyses without matching healthy control group, we cannot conclude whether baseline NAA and tCr levels were abnormally low in the study sample or tamoxifen treatment "normalized" these levels. Additionally, different baseline tCr levels in tamoxifen and placebo groups, but not in response groups, despite similar demographic and clinical characteristics achieved with randomization may be considered as a limitation. With our current understanding of bipolar mania pathogenesis, we can explain neither this difference nor its potential effect on our findings. Therefore, the observed effects of tamoxifen treatment may represent a regression toward the mean rather than a medication effect. Owing to technical limitations we did not perform a 31P MRS study, so no direct measurement of cerebral energetic phosphorus metabolites could be made. Of the four brain regions (DMPFC, right basal ganglia, frontal lobe, and right hippocampus) initially investigated, we selected only the DMPFC as the region of interest for the current study and correction for multiple comparison was not conducted. Nevertheless, for MRS experiments involving severely manic patients, a sample size of 48 was relatively large and allocation of patients as their own controls was methodologically sound. That together with the longitudinal design and minimized confounding medication effects and head motion have resulted in detection of some important associations between the DMPFC tCr and NAA levels and antimanic treatment response. The worsening of subjects on placebo, in addition to the improvement of subjects receiving tamoxifen, contributed to some of the correlations observed. BD is a disorder with changing severity over time, and it is not surprising that some subjects had worsening symptoms during the study period. The observation of correlations between severity and metabolite markers should be valid across various states of illness, including improvement and worsening of symptoms, if they are mechanistically related to mood state, as suggested by these results.

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating neurochemical alterations in DMPFC associated with treatment response to a PKC inhibitor used for bipolar mania. Reported findings on the DMPFC tCr and NAA levels are in line with the accumulated molecular and clinical evidence on the mitochondrial dysfunction in BD (1), implicating a direct involvement of PKC inhibition in disease pathophysiology and antimanic treatment response. This information adds to current evidence of BD pathophysiology and the mechanistic understanding of antimanic treatment response. The failure of previous studies to establish such a link could be related with cross-sectional designs, medication effects, and practical difficulty in working with bipolar manic patients (32). The value of tCr and NAA as biomarkers of brain energy metabolism in bipolar manic state and of antimanic treatment response need to be investigated in larger longitudinal 1H and 31P MRS studies, preferably conducted in conjunction with clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The clinical study was supported by the research grant 02T-162 from the Stanley Medical Research Institute (A. Yildiz). The 1H MRS study was supported by the American Psychiatric Association/Astra Zeneca Young Minds in Psychiatry Award to A. Yildiz, and research grants from Harvard Medical School, the Bipolar Research Center, Stanley Foundation, Belmont, MA (A. Yildiz), the International Sleep Research Foundation, Houston, TX (A. Yildiz), and MH 58681 (P.F. Renshaw).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Preliminary findings of this study were presented in at the 28th Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Financial Disclosures

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Ayşegül Yildiz, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey International Consortium for Bipolar Disorder Research & Psychopharmacology Program, McLean Division of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Burç Aydin, Department of Medical Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey

Necati Gökmen, Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, School of Medicine, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey

Ayşegül Yurt, Department of Medical Physics, Health Sciences Institute, Dokuz Eylul University, İzmir, Turkey

Bruce Cohen, Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Program, Mclean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA

Pembe Keskinoglu, Department of Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey

Dost Öngür, Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Program, Mclean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA

Perry Renshaw, Brain Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

References

- 1.Stork C, Renshaw PF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: Evidence from magnetic resonance spectroscopy research. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:900–919. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leboyer M, Soreca I, Scott J, Frye M, Henry C, Tamouza R, et al. Can bipolar disorder be viewed as a multi-system inflammatory disease? J Affect Disord. 2012;141:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreazza AC, Young LT. The neurobiology of bipolar disorder: identifying targets for specific agents and synergies for combination treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:1039–1052. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catapano LA, Manji HK. Kinases as drug targets in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanetti MV, Loch A, Machado-Vieira R. Translating biomarkers and bio-molecular treatments into clinical practice: assessment of hypothesis driven clinical trial data. In: Yildiz A, Ruiz P, Nemeroff C, editors. The Bipolar Book. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resin GT, Andreazza AC. Oxidative damage and its treatment impact. In: Yildiz A, Ruiz P, Nemeroff C, editors. The Bipolar Book. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnbaum SG, Yuan PX, Wang M, Vijayraghavan S, Bloom AK, Davis DJ, et al. Protein kinase C overactivity impairs prefrontal cortical regulation of working memory. Science. 2004;306:882–884. doi: 10.1126/science.1100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szabo ST, Machado-Vieira R, Yuan PX, Wang Y, Wei YL, Falke C, et al. Glutamate receptors as targets of protein kinase C in the pathophysiology and treatment of animal models of Mania. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einat H, Yuan P, Szabo ST, Dogra S, Manji HK. Protein kinase C inhibition by tamoxifen antagonizes manic-like behavior in rats: implications for the development of novel therapeutics for bipolar disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;55:123–131. doi: 10.1159/000106054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrial E, Etievant A, Betry C, Scarna H, Lucas G, Haddjeri N, et al. Protein kinase C regulates mood-related behaviors and adult hippocampal cell proliferation in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;43:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einat H, Manji HK. Cellular plasticity cascades: Genes-to-behavior pathways in animal models of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cechinel-Recco K, Valvassori SS, Varela RB, Resende WR, Arent CO, Vitto MF, et al. Lithium and tamoxifen modulate cellular plasticity cascades in animal model of mania. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1594–1604. doi: 10.1177/0269881112463124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yildiz A, Guleryuz S, Ankerst DP, Ongur D, Renshaw PF. Protein kinase C inhibition in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:255–263. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turecki G, Grof P, Cavazzoni P, Duffy A, Grof E, Ahrens B, et al. Evidence for a role of phospholipase C-gamma 1 in the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:534–538. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum AE, Akula N, Cabanero M, Cardona I, Corona W, Klemens B, et al. A genome-wide association study implicates diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH) and several other genes in the etiology of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:197–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang HY, Friedman E. Enhanced protein kinase C activity and translocation in bipolar affective disorder brains. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:568–575. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman E, Wang HY, Levinson D, Connell TA, Singh H. Altered platelet protein kinase C activity in bipolar affective disorder, manic episode. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33:520–525. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bebchuk JM, Arfken CL, Dolan-Manji S, Murphy J, Hasanat K, Manji HK. A preliminary investigation of a protein kinase C inhibitor in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:95–97. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulkarni J, Garland KA, Scaffidi A, Headey B, Anderson R, de Castella A, et al. A pilot study of hormone modulation as a new treatment for mania in women with bipolar affective disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:543–547. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarate CA, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Quiroz J, Jolkovsky L, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Efficacy of a protein kinase C inhibitor (tamoxifen) in the treatment of acute mania: A pilot study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clay HB, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29:311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cataldo AM, McPhie DL, Lange NT, Punzell S, Elmiligy S, Ye NZ, et al. Abnormalities in mitochondrial structure in cells from patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:575–585. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.081068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CC, Jou SH, Lin TT, Liu CS. Mitochondrial DNA variation and increased oxidative damage in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68:551–557. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dager SR, Friedman SD, Parow A, Demopulos C, Stoll AL, Lyoo IK, et al. Brain metabolic alterations in medication-free patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:450–458. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraguljac NV, Reid M, White D, Jones R, den Hollander J, Lowman D, et al. Neurometabolites in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:111–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frey BN, Stanley JA, Nery FG, Monkul ES, Nicoletti MA, Chen HH, et al. Abnormal cellular energy and phospholipid metabolism in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of medication-free individuals with bipolar disorder: An in vivo 1H MRS study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(Suppl 1):119–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamakawa H, Murashita J, Yamada N, Inubushi T, Kato N, Kato T. Reduced intracellular pH in the basal ganglia and whole brain measured by 31P-MRS in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yildiz A, Gokmen N, Kucukguclu S, Yurt A, Olson D, Rouse ED, et al. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic examination of benzodiazepine action in humans. Psychiatry Res. 2010;184:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildiz A, Mantar A, Simsek S, Onur E, Gokmen N, Fidaner H. Combination of pharmacotherapy with electroconvulsive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: A pilot controlled trial. J ECT. 2010;26:104–110. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181c189f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davanzo P, Thomas MA, Yue K, Oshiro T, Belin T, Strober M, et al. Decreased anterior cingulate myo-inositol/creatine spectroscopy resonance with lithium treatment in children with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:359–369. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strawn JR, Patel NC, Chu WJ, Lee JH, Adler CM, Kim MJ, et al. Glutamatergic effects of divalproex in adolescents with mania: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider MR, Fleck DE, Eliassen JC, Strakowski SM. Structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging findings and their treatment impact. In: Yildiz A, Ruiz P, Nemeroff C, editors. The Bipolar Book. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magnet Reson Med. 1993;30:672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amrollahi Z, Rezaei F, Salehi B, Modabbernia AH, Maroufi A, Esfandiari GR, et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled 6-week study on the efficacy and safety of the tamoxifen adjunctive to lithium in acute bipolar mania. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DelBello MP, Cecil KM, Adler CM, Daniels JP, Strakowski SM. Neurochemical effects of olanzapine in first-hospitalization manic adolescents: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1264–1273. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quiroz JA, Gray NA, Kato T, Manji HK. Mitochondrially mediated plasticity in the pathophysiology and treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2551–2565. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuksel C, Du F, Ravichandran C, Goldbach J, Thida T, Lin P, et al. Abnormal high energy phosphate molecule metabolism during regional brain activation in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:84–84. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moretti M, Valvassori SS, Steckert AV, Rochi N, Benedet J, Scaini G, et al. Tamoxifen effects on respiratory chain complexes and creatine kinase activities in an animal model of mania. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;98:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steckert AV, Valvassori SS, Mina F, Lopes-Borges J, Varela RB, Kapczinski F, et al. Protein kinase C and oxidative stress in an animal model of mania. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2012;9:47–57. doi: 10.2174/156720212799297056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zarate CA, Manji HK. Protein kinase C inhibitors rationale for use and potential in the treatment of bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:569–582. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923070-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamin LS. Statistical treatment of the law of initial values (Liv) in autonomic research: A review and recommendation. Psychosom Med. 1963;25:556–566. doi: 10.1097/00006842-196311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yildiz A, Vieta E, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ. Factors modifying drug and placebo responses in randomized trials for bipolar mania. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:863–875. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyoo IK, Renshaw PF. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Current and future applications in psychiatric research. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.