Abstract

Given the strong association between early behavior problems and language impairment, we examined the effect of a brief home-based adaptation of Parent–child Interaction Therapy on infant language production. Sixty infants (55% male; mean age 13.47 ± 1.31 months) were recruited at a large urban primary care clinic and were included if their scores exceeded the 75th percentile on a brief screener of early behavior problems. Families were randomly assigned to receive the home-based parenting intervention or standard pediatric primary care. The observed number of infant total (i.e., token) and different (i.e., type) utterances spoken during an observation of an infant-led play and a parent-report measure of infant externalizing behavior problems were examined at pre- and post-intervention and at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Infants receiving the intervention demonstrated a significantly higher number of observed different and total utterances at the 6-month follow-up compared to infants in standard care. Furthermore, there was an indirect effect of the intervention on infant language production, such that the intervention led to decreases in infant externalizing behavior problems from pre- to post-intervention, which, in turn, led to increases in infant different utterances at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups and total utterances at the 6-month follow-up. Results provide initial evidence for the effect of this brief and home-based intervention on infant language production, including the indirect effect of the intervention on infant language through improvements in infant behavior, highlighting the importance of targeting behavior problems in early intervention.

Keywords: language production, infancy, behavior problems, parenting, early intervention

Externalizing behavior problems are the most common reason young children are referred for mental health services (Keenan & Wakschlag, 2000). In fact, prevalence rates of clinically elevated levels of externalizing behavior problems in toddlers are as high as 15% (Carter et al., 2004). By 2 years, high levels of externalizing problems predict more severe school-age conduct problems (Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003) and greater increases in later internalizing problems (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). Early externalizing problems also persist without treatment, with more than half of preschoolers with a disruptive behavior disorder continuing to have a diagnosis 4 years later (Lavigne et al., 1998).

LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT AND EXTERNALIZING BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

In addition to the stability and long-term negative behavioral consequences of early externalizing behavior problems, research has documented a strong relation between early externalizing behavior problems and language difficulties (Benner, Nelson, & Epstein, 2002). Specifically, young children with externalizing behavior problems are more likely to have difficulties in language, and children with language delays are at increased risk for externalizing behavior problems (Qi & Kaiser, 2003). Meta-analytic research suggests that language impairment in children doubles the risk for subsequent increases in externalizing behavior problems (Yew & O’Kearney, 2013). Additionally, early language impairment at 5 years has been shown to predict young adult psychiatric disorders (Beitchman et al., 2001) and delinquent and aggressive behaviors (Brownlie et al., 2004). Therefore, research documenting this association in childhood and adolescence suggests the direction of the effect seems to be from language impairment to externalizing behavior problems, although causality is difficult to determine without a true experimental design.

Considerably less work has examined the relation between externalizing behavior problems and language impairment in the first 2 years of life when children typically learn to speak and begin to display elevated levels of externalizing problems. On the one hand, a cross-sectional study of 19-month-old twins yielded a modest association between physical aggression and expressive vocabulary, and quantitative genetic modeling suggested a significant path from expressive vocabulary to aggression (Dionne, Tremblay, Boivin, Laplante, & Perusse, 2003). On the other hand, toddler aggression predicted subsequent decreases in academic skills 5 years later, and an intervention targeting early behavior problems, the Family Check-Up (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007), led to improvements in academic skills through decreases in toddler aggression (Brennan, Shaw, Dishion, & Wilson, 2012). Thus, given the increasing support for reliably detecting externalizing problems by 12 months (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Bosson-Heenan, Guyer, & Horwitz, 2006), it is possible that early externalizing problems may precede or coincide with the development of expressive language during the first 2 years of life.

POVERTY EXACERBATES BOTH EXTERNALIZING BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS AND LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT

In addition to the association between externalizing behavior problems and language impairment, poverty represents a shared risk factor for both problems. Young children in poverty are twice as likely to have an expressive language delay (Horwitz et al., 2003) and global developmental delay (Simpson, Colpe, & Greenspan, 2003) and are three times as likely to exhibit externalizing behavior problems (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Skuban, & Horwitz, 2001). In addition, among children with developmental delay, underrepresented minority families are more likely to live in poverty (Emerson, 2004). Among children in Head Start, boys were 50% more likely to have lower language scores when rated as having higher levels of externalizing behavior problems by parents (Kaiser, Hancock, Cai, Foster, & Hester, 2000) and teachers (Kaiser, Cai, Hancock, & Foster, 2002). Furthermore, parenting practices have been shown to mediate the effect of chronic poverty on child externalizing behavior problems (Pachter, Auinger, Palmer, & Weitzman, 2006) and language abilities (Raviv, Kessenich, & Morrison, 2004). Indeed, seminal research by Hart and Risley (1995) demonstrated the staggeringly low number (and quality) of words parents spoke to their child during the first 3 years of life among families living in poverty relative to working-class and professional families (i.e., “the 30 million word gap by age 3”) and the negative effect the low input of parent language had on subsequent child language. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of targeting parenting in interventions for externalizing behavior problems and language impairment among children from low-income families.

EARLY INTERVENTIONS TARGETING EXTERNALIZING BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

There has been a strong research base for the use of behavioral parent-training interventions in the treatment of preschool externalizing behavior problems (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008). Less work, however, has been conducted in children younger than 3 years despite increased support for the identification and stability of externalizing behavior problems from 12 to 24 months (Alink et al., 2006; van Zeijl et al., 2006). A brief intervention with strong empirical support is the Family Check-Up, which has led to decreases in toddler externalizing behavior problems and improvements in parenting across two randomized trials (Dishion et al., 2008; Shaw, Dishion, Supplee, Gardner, & Arnds, 2006). In fact, recent findings revealed that the Family Check-Up also led to improvements in academic skills and letter-word identification through improvements in toddler aggression (Brennan et al., 2012), although effect sizes of the indirect effects were relatively small and the intervention did not target children younger than 2 years.

Targeting externalizing problems in infancy (defined herein as younger than 2 years) would likely require shorter interventions as parents are just beginning to face challenges with their infant’s increased mobility and desire to exert independence. Intervening before behavior problems become entrenched would be ideal for infants from low-income families, who are at higher risk for behavior and language problems (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2006; Horwitz et al., 2003) and more likely to drop out from longer parenting treatment programs (Bagner & Graziano, 2013; Lavigne et al., 2010). Recent work has demonstrated the efficacy of the Infant Behavior Program, a home-based adaptation of the Child-Directed Interaction phase of Parent–child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), in improving externalizing behavior problems in infants aged 12 to 15 months from low-income, ethnic minority families (Bagner et al., in press; Bagner, Rodríguez, Blake, & Rosa-Olivares, 2013). To our knowledge, however, studies on this and other interventions targeting early externalizing behavior problems have not examined the intervention’s direct effect on language despite the well-documented association between behavior and language problems.

EARLY INTERVENTIONS TARGETING LANGUAGE PROBLEMS

Similar to the literature on interventions targeting early behavior problems, there has been a strong evidence base for interventions targeting language problems in young children. For example, Dialogic Reading (DR) is an empirically -based picture book reading intervention for at-risk preschoolers that has been shown to improve child letter and sound identification (Whitehurst et al., 1999), expressive language (Hargrave & Sénéchal, 2000; Whitehurst et al., 1994), and literacy gains for children from low-income, minority families (Zevenbergen, Whitehurst, & Zevenbergen, 2003) and with language delays (Crain-Thoreson & Dale, 1999; Hargrave & Sénéchal, 2000). For toddlers with receptive and/or expressive language delay, a randomized controlled trial of the Enhanced Milieu Teaching, a caregiver-based intervention targeting early language acquisition, demonstrated effects on receptive but not expressive language (Roberts & Kaiser, 2015). For toddlers with expressive (but not receptive) language delay, a randomized controlled trial of the Heidelberg Parent-based Language Intervention, a parenting intervention focusing on interactions during picture book sharing, demonstrated intervention effects on expressive language (Buschmann et al., 2009). For toddlers with autism spectrum disorder, promising effects on language have been demonstrated for the Hanen’s More Than Words program (Carter et al., 2011) and the Early Start Denver Model (Dawson et al., 2010), both of which incorporate parent implementation of the intervention.

Despite the promising findings of these interventions targeting child language problems, only a few studies reported on the effects of the intervention on child behavior. For example, an adaptation of DR for preschoolers in Head Start led to improvements in both vocabulary and literacy, as well as problem solving and emotional understanding (Bierman et al., 2008). However, effects were not as strong for externalizing behavior problems, such as aggression, and DR has not been empirically tested with children younger than 2 years. For 6- to 10-month-old infants, promising work by Landry and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that a home-based parenting intervention called Playing and Learning Strategies led to improvements in both communication and negative affectivity, but externalizing behavior problems were not measured because all children were younger than 12 months, the earliest age at which externalizing behavior problems has been reliably assessed. Results on the Hanen’s More Than Words program suggested baseline toddler behavior (i.e., object interest) moderated the effect of the intervention on communication improvements (Carter et al., 2011), and findings on the Early Start Denver Model demonstrated improvements in language and overall adaptive behavior (Dawson et al., 2010). However, these studies on interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder did not examine the effect of the intervention on externalizing behavior problems. Therefore, it is unclear as to the extent to which early interventions targeting language can also influence externalizing behavior problems.

CURRENT STUDY

Taken together, there are equally substantial and compelling literatures documenting the efficacy of early intervention programs targeting externalizing behavior problems and early intervention programs targeting language. However, only a few studies examined the impact of one intervention on both behavior and language (Bierman et al., 2008; Brennan et al., 2012), and none to our knowledge examined the specific effect of an intervention on externalizing behavior problems and expressive language in infants. Therefore, the primary goal of the current study was to examine the direct effect of the Infant Behavior Program, a home-based adaptation of the Child-Directed Interaction phase of PCIT for externalizing behavior problems in high-risk 12- to 15-month-olds, on infant expressive language. We predicted that relative to infants in a control group, infants receiving the intervention would use a significantly higher number of different and total utterances spoken during an observation of an infant-led play at a post-intervention assessment, as well as at 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

In addition to the direct effect of the intervention on infant expressive language, we predicted that decreases in parent-reported infant externalizing behavior problems from pre- to post-intervention would mediate the effect of the intervention on subsequent increases in infant different and total utterances at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Although findings are mixed as to whether or not externalizing behavior problems precede or are a result of language impairment, research suggests that expressive language delay is not typically diagnosed until at least 18 months (Horwitz et al., 2003), whereas clinically elevated levels of externalizing behavior problems at 12 to 17 months are moderately stable over time (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2006). Furthermore, research on the Family Check-Up demonstrated that decreases in toddler aggression mediated the effect of the intervention on subsequent academic skills 5 years later. Thus, we predicted that early externalizing behavior problems may represent an important mechanism by which a parenting intervention affects infant expressive language.

Method

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were 60 mothers and their 12- to 15-month-old infant, who were recruited at a large hospital-based pediatric primary care clinic for underserved families. Infants were 55% male, with a mean age of 13.47 months (SD = 1.31). Most mothers identified themselves (95%) and their infant (98%) as being from an ethnic or racial minority group, with the majority reporting a Hispanic ethnicity (90% of mothers and 93% of infants). Bilingual mothers were asked to choose their language preference based on their comfort level. Of the 54 mothers self-identifying as Hispanic, 34 (63%) completed the screening and assessments in Spanish. A majority of families (60%) had incomes below the poverty line, and the median annual income for all families was $18,513. See Table 1 for a summary of participant demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Demographic Variables by Initial Group Assignment

| Total Sample (n = 60) |

Intervention group (n = 31) |

Standard Care group (n = 29) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | p value | |

| Child sex (male) | 55 | 33 | 58 | 18 | 52 | 15 | .622 |

| Child minority status | 98 | 59 | 97 | 30 | 100 | 29 | .697 |

| Mother minority status | 95 | 57 | 94 | 29 | 97 | 28 | .536 |

| Mother English speaking (vs. Spanish) | 43 | 26 | 55 | 17 | 31 | 9 | .074 |

| High school graduate or less | 70 | 42 | 65 | 20 | 76 | 22 | .338 |

| Below poverty line * | 60 | 35 | 58 | 18 | 63 | 17 | .704 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p value | |

|

| |||||||

| Child age (months) | 13.47 | 1.31 | 13.71 | 1.40 | 13.21 | 1.18 | .138 |

| Mother age (years) | 29.57 | 5.49 | 30.03 | 5.50 | 29.07 | 5.54 | .502 |

| Mother IQ T-Score ** | 46.35 | 12.55 | 47.21 | 12.17 | 45.43 | 13.09 | .588 |

| BITSEA Problem score | 20.15 | 8.10 | 22.02 | 9.22 | 18.35 | 6.55 | .076 |

Note: BITSEA = Brief Infant-Toddler Social-Emotional Assessment.

Two mothers did not report income, and both were in the standard care group.

T-Scores are combined between the WASI and EIWA-III Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests.

For study inclusion, the primary caregiver was required to rate their infant above the 75th percentile on the problem scale of the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006), a screener of infant behavior problems, and speak and understand either English or Spanish. To ensure ability to learn skills taught during the intervention, the primary caregiver was required to receive an estimated IQ score ≥ 70 on the two-subtest (vocabulary and matrix reasoning) version of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999) for those speaking English or an average standard score ≥ 4 on the vocabulary and matrix reasoning subtests of the Escala de Inteligencia Wechsler Para Adultos – Third Edition (Pons, Flores-Pabón, et al., 2008) for those speaking Spanish. Major infant sensory impairments (e.g., deafness, blindness) or motor impairments that significantly impair mobility, as well as current child protection services involvement, were exclusion criteria, although no families were excluded based on these criteria.

STUDY DESIGN AND PROCEDURE

This study, approved by both the University and Hospital Institutional Review Boards, was a randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of the Infant Behavior Program (described below) in reducing behavior problems in at-risk infants. In the main outcome study, we found that relative to infants receiving standard pediatric care, infants receiving the intervention demonstrated improvements in observed and parent-reported behavior problems (Bagner et al., in press). In the current study, we were interested in examining the effect of the intervention on infant language and the indirect effect of the intervention on infant language through changes in infant externalizing behavior problems. Families were actively recruited during well and sick visits at a large hospital-based pediatric primary care clinic for underserved families.

Of the 147 families that agreed to participate in the screening, 60 (41%) met study criteria and were enrolled and randomized (using a computer-generated random numbers list) to the intervention (n = 31) or standard care (n = 29). In the standard care group, infants continued to receive health care, including well and sick visits, at the pediatric primary care clinic but did not receive the intervention (described in more detail below). The groups did not differ on any demographic or baseline characteristics (see Table 1). Of the 60 families randomized to group, 58 (n = 30 in the intervention group and n = 28 in the standard care group) completed a baseline assessment in their home and were informed of their group status, and we were unable to contact the other two families after the screening. Families also participated in a post (n = 48; 80% retention) assessment 2 months after the baseline and follow-up (n = 46; 77% retention) assessments 3- and 6-months after the post-assessment. During these assessments, the mothers completed the parent-report questionnaire on infant behavior and were videotaped during a 5-minute infant-directed play observation, in which most mothers spoke Spanish (35%) or a combination of Spanish and English (52%) with their infant. Additionally, mothers were provided with a standardized set of toys to use during this observation (and different toys from those used during the intervention sessions), which was consistent across participants. Independent assessors masked to group status conducted the assessments and provided standardized instructions prior to the infant-led play for the parent to follow their infant’s lead in play. Families received $50 for participation in each assessment.

SCREENING MEASURES

Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006)

The BITSEA is a 31-item, nationally standardized screener designed to assess behavioral problems and competencies in 12- to 36-month-olds and has been published and is available in both English and Spanish. The problem scale of the BITSEA has strong evidence for test-retest and interrater reliability (Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006) and discriminative validity for those scoring above the clinical cutoff of the 75th percentile (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel, & Cicchetti, 2004), as well as documented reliability and validity for the Spanish version (Hungerford, Garcia, & Bagner, 2015). Examples of items on the problem scale include “restless and can’t sit still,” “is destructive,” and “hits, bites or kicks” and are rated on a scale from 0 (not true/rarely), 1 (somewhat true/sometimes), or 2 (very true/often). Infants scoring above the 75th percentile on the BITSEA problem scale were included in the study, and overall Cronbach’s alpha with the current sample was .80 (.86 for English version and .74 for Spanish version).

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 1999) and Escala de Inteligencia Wechsler Para Adultos – Third Edition (EIWA-III; Wechsler, 2008)

The WASI is a brief measure of intelligence with high reliability and validity (Hays, Reas, & Shaw, 2002), and the EIWA-III is a published Spanish version of the full Wechsler Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1997) that has received strong support in the literature for both reliability (Pons, Flores-Pabón, et al., 2008) and validity (Pons, Matías-Carrelo, et al., 2008). The vocabulary and matrix reasoning subtests were administered, and mothers were required to receive an estimated IQ score ≥ 70 on the two-subtest version of the WASI or an average standard score ≥ 4 on the EIWA-III subtests, although no mothers were excluded based on this criterion.

MEASURES OF INFANT BEHAVIOR AND LANGUAGE

Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006)

The ITSEA is a 166-item, nationally standardized questionnaire designed to assess behavioral problems and competencies in 12- to 36-month-olds and has been published and is available in both English and Spanish. The ITSEA has excellent test-retest reliability (r = .85 to .91) and very good interrater reliability (r = .70 to .76; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006), including support for high persistence of elevated behavior problems with the youngest age group of 12 to 23 months (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2006). Furthermore, research on the ITSEA provides evidence for validity with other parent-report and observational measures (Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003). The aggressive/defiance subscale was used as a measure of infant externalizing behavior problems, and overall Cronbach’s alpha with the current sample was .77 (.81 for English version and .75 for Spanish version).

The Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES; MacWhinney, 2000)

The CHILDES is one of the most widely used and psychometrically valid tools to examine child language (Corrigan, 2011) and was used in the current study to examine infant language use during the 5-minute observation of infant-led play. The CHILDES is a set of computational tools and consists of three sections: (a) codes for human analysis of transcripts (CHAT), (b) database of language transcripts in several languages, including Spanish, and (c) computerized language analysis (CLAN). The CHAT program provides a standardized way of creating language transcripts, while the database helps to improve the accuracy of the transcription. The CLAN program provides strong psychometric support for analyzing language transcripts (Parker & Brorson, 2005). We transcribed infant language use at all time points using CHAT and examined the number of total utterances spoken (i.e., “tokens”) and the number of different utterances spoken (i.e., diversity of utterances or “types”) using CLAN. Total utterances spoken are calculated by the sum of all word approximations and words produced, whereas different utterances spoken is a measure of lexical diversity and is calculated by the sum of all “unique” utterances and words spoken. For example, an infant who says, “ma, ma, ma, da, da, da” produced 6 total utterances and 2 different utterances. In the below analyses, the infant’s total number of utterances spoken at baseline was included both as an outcome and as a covariate to provide a more accurate estimate of different utterances spoken at the post and follow-up assessments. Specifically, two trained and bilingual (English and Spanish) undergraduate research assistants, uninformed to group status, transcribed infant language using the CHAT and database, and all transcriptions were analyzed using the automated CLAN program (and specified when the language was in English or Spanish). Twenty percent of the transcripts were transcribed again by a second research assistant to assess reliability, and interrater reliability estimates were 87% (ICC = .97) for different utterances and 91% (ICC = .98) for total utterances.

INTERVENTION DESCRIPTION

The Infant Behavior Program is a home-based adaptation of the Child-Directed Interaction phase of PCIT, an evidence-based intervention for preschool behavior problems (Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson, & Touyz, 2003; Schuhmann, Foote, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, 1998), for at-risk infants. Consistent with recommendations to adapt interventions for new populations (Eyberg, 2005), we maintained the core features of PCIT while addressing the unique developmental needs of infants. Similar to standard PCIT, in the first teach session, the therapist taught the parent(s) to follow their infant’s lead in play by decreasing don’t skills (i.e., commands, questions, and negative statements) and increasing do skills (i.e., PRIDE: Praising the infant, Reflecting the infant’s speech, Imitating the infant’s play, Describing the infant's behavior, and expressing Enjoyment in the play). Parents were taught to direct the PRIDE skills to their infant’s appropriate play and ignore disruptive behaviors (e.g., hitting, whining). Following the teach session, parent skills were assessed during a 5-minute observation at the start of each coach session, and data collected were used by the therapist to coach the parent(s) in their use of the skills. In addition to standard coaching practices, therapists incorporated strategies relevant for infants. For example, given lower receptive language abilities in infants, parents were encouraged to use nonverbal praise (e.g., clapping) along with verbal praise to enhance reinforcement for appropriate behaviors. Furthermore, consistent with research on PCIT for children with developmental delay (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007), parents were encouraged to repeat infant vocalizations.

Intervention Format and Fidelity

Sessions were conducted weekly with each family in their home and lasted approximately 1 to 1.5 hours. The therapists were all doctoral students in clinical psychology and trained by the first author, who is a PCIT Master Trainer. In each session, the therapist problem solved with each family ways to optimize in-home coaching, such as choosing an appropriate location for the session and developing ways to minimize distractions (e.g., turning off the television). Parents were instructed to practice the skills described above for 5 minutes each day with their infant and were asked to complete weekly logs to document frequency of practice. Of the 28 families attending the first session, 8 (29%) dropped out before completing the intervention, which is consistent with dropout rates in standard PCIT (e.g., 36%; Eyberg, Boggs, & Jaccard, 2014) and is relatively low given the high-risk nature of the current sample. On average, families completed the intervention in 6.1 sessions (range from 5 to 7 sessions).

All sessions were videotaped, and 63% of sessions were randomly selected and coded for fidelity. Average fidelity across sessions, defined as the percent with which the therapist adhered to key elements of each session detailed in the manual, was 97%. Of the coded tapes, 40% were randomly selected and coded a second time for fidelity and yielded an interobserver reliability estimate of 95%.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using SPSS v. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., 2009). Missing data due to incomplete assessments occurred at a low rate with 6.6% of data missing, overall. Little’s MCAR test was not statistically significant, χ2 (40) = 28.88, p = .90, indicating no evidence of bias due to missing data, and therefore data were assumed to be at least missing at random (MAR). Given this assumption, an expectation maximization (EM) algorithm was used to account for missing data. Data analysis thus includes the full sample of 58 participants for whom any data were present. In a simulation study, Newman (2003) reported that, for three-wave longitudinal studies where data are MAR or MCAR and 25% of data are missing, EM, full information maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation perform similarly with respect to introducing minimal bias into statistical estimates.

Prior to analysis the data were evaluated for multivariate outliers with respect to leverage, discrepancy, and influence. Leverage indices for each individual were examined, as well as externally studentized residuals and dfbetas. One case was identified as a statistical outlier, consistently falling outside acceptable boundaries for leverage, discrepancy, and influence. Identical conclusions were drawn with and without the outlier in the analysis and the results presented include the outlier to better represent the population of interest.

For examination of intervention effects on infant language production, ordinary least squares analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted with a two-group (intervention or standard care) comparison and using baseline scores as a covariate to increase statistical power (Rausch, Maxwell, & Kelley, 2003). The single degree of freedom contrast focuses on comparison of adjusted means at post-intervention and follow-ups. For statistically significant tests, effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d values, for which Cohen (1977) defines small, medium, and large effects as .20, .50, and .80, respectively. For a sample of n = 58, α = .05, and a single degree of freedom contrast, the present study achieved power of .85 for a large effect and .46 for a medium effect.

For examination of the indirect effects models, the INDIRECT program for mediation effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was employed, which estimates total, direct, and indirect effects, allowing for the inclusion of covariates in the models. The INDIRECT program uses a nonparametric resampling procedure with n = 5,000 bootstrap resamples to derive point estimates and 95% bias corrected and accelerated confidence intervals for the indirect effects. An indirect effect was considered statistically significant when the confidence interval of the indirect effect (a × b) pathway, did not include zero.

Results

Means and standard deviations of, as well as intercorrelations between, study variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Study Measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline Different Utterances | – | ||||||

| 2. Post-Treatment Different Utterances |

.49*** | – | |||||

| 3. 3-Month Follow-up Different Utterances |

.48*** | .53*** | – | ||||

| 4. 6-Month Follow-up Different Utterances |

.44** | .54*** | .39** | – | |||

| 5. Baseline Externalizing Behavior | .14 | .21 | .15 | .18 | – | ||

| 6. Post-Treatment Externalizing Behavior |

.27* | .20 | .08 | −.11 | .73*** | – | |

| 7. Infant Age (Months) | .21 | .04 | .07 | .18 | .00 | .18 | – |

|

Means and Standard Deviations Total Sample |

17.31 (12.56) |

19.15 (14.56) |

31.93 (28.64) |

47.77 (23.39) |

0.79 (0.40) |

0.81 (0.41) |

13.52 (1.30) |

| Intervention Group | 14.73 (10.06) |

18.79 (14.06) |

30.16 (25.83) |

54.63 (16.00) |

0.81 (0.35) |

0.74 (0.36) |

13.77 (1.38) |

| Standard Care Group | 20.07 (14.46) |

19.54 (15.33) |

33.83 (31.75) |

40.41 (27.78) |

0.77 (0.45) |

0.88 (0.44) |

13.25 (1.18) |

IMPACT OF INTERVENTION ON INFANT LANGUAGE PRODUCTION

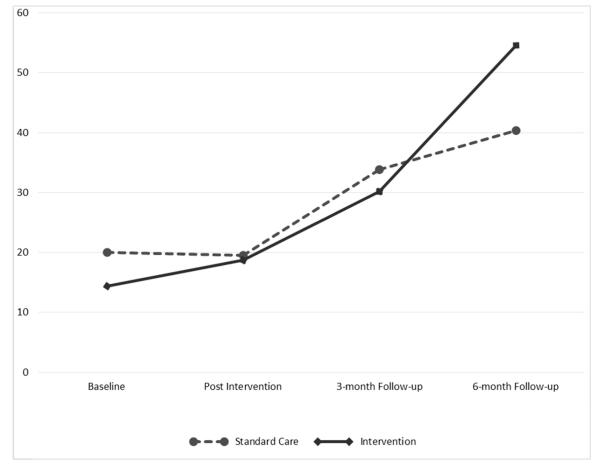

In order to examine the impact of the intervention on infant language production at post-intervention, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up, ANCOVAs were evaluated with infant language production (i.e., different utterances spoken during the infant-directed play) as the dependent variable and group (intervention vs. standard care) as the independent variable. Infant age at baseline, infant sex, maternal education level, and language spoken at home were entered as covariates, as well as baseline language production scores (both total utterances and different utterances spoken during the infant-direct play), to account for possible differences in infant language skills across the sample. At post-treatment, infants in the intervention group did not use significantly more different utterances than infants in the standard care group, F(7, 50) = 0.84, p = .36. At the 3-month follow-up, infants in the intervention group did not use significantly more different utterances than infants in the standard care group, F(7, 50) = 0.07, p = .80. However, at the 6-month follow-up, infants in the intervention group used significantly more different utterances than children in the standard care group, F(7, 50) = 13.91, p < .001, d = .63. Figure 1 depicts the means of language production at each time point for both the intervention and standard care groups. Of note, analyses were repeated using total utterances spoken during an infant-directed play as the dependent variable, and results showed a similar pattern. Specifically, infants in the intervention group used significantly more total utterances at the 6-month follow-up than infants in the standard care group, F(7, 50) = 17.19, p < .001, d = .77, but there were no significant differences at any other earlier time points.

FIGURE 1.

Trajectories of Different Utterances Spoken for Intervention and Standard Care Groups.

INDIRECT EFFECT OF INTERVENTION ON LANGUAGE PRODUCTION VIA REDUCED EXTERNALIZING BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

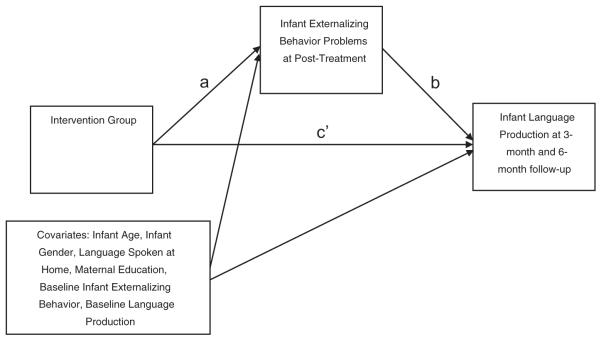

To test the hypothesis that the association between intervention group and infant language production at 3- and 6-month follow-ups would be accounted for by change in aggression/defiance scores at post-intervention, the INDIRECT program for mediation effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was employed to estimate the indirect effects and 95% bias corrected and accelerated confidence intervals. The INDIRECT program provided five relevant path coefficients in its output, provided in Table 3: a coefficient (a) for the path from the independent variable (i.e., intervention group) to the mediator (ITSEA aggression/defiance scores at post-intervention); a coefficient (b) for the path from the mediator to the dependent variable (i.e., different utterances spoken at 3- and 6-month follow-ups); a coefficient (a*b) for the indirect effect of intervention group on infant language production through aggression/defiance scores; a coefficient (c) for the total effect of intervention group on infant language production; and a coefficient (c’) for the direct effect (i.e., the total effect minus the indirect effect). Consistent with analyses on the direct effect of the intervention on infant language production, all of the coefficients included infant age at baseline, infant sex, maternal education level, language spoken at home, and baseline language production (i.e., both total and different utterances spoken at baseline) as covariates; baseline ITSEA aggression/defiance scores were entered as an additional covariate. The indirect effects model is presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Summary of Point Estimates for Indirect Effects of Intervention Group Predicting Language Use at Follow-up

| Effect of IV on M |

Effect of M on DV |

Direct Effect |

Total Effect of IV on DV |

Indirect Effect |

95% BCA CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (DV) | (a) | (b) | (c’) | (c) | (a × b) | |

| 1. Different Utterances at 3-month FU |

−0.23** | −25.73 | −4.56 | 1.45 | 6.01 a | 1.53, 14.33 |

| 2. Different Utterances at 6-month FU |

−0.23** | −37.25*** | 11.60* | 20.31*** | 8.70 a | 2.64, 16.73 |

Note. IV = independent variable (intervention group); M = mediator (ITSEA aggression/defiance score at post-intervention); DV = dependent variable; BCA CI = bias corrected and accelerated confidence interval; FU = follow-up;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

Signifies significant indirect effects; 5,000 bootstrap samples.

FIGURE 2.

Proposed Effect of Intervention Group on Language Production via Infant Externalizing Behavior Problems.

As hypothesized, the indirect effect of intervention group on infant language production at the 3-month follow-up via ITSEA aggression/defiance scores at post-intervention was statistically significant (see the a × b column in Table 3). In addition, the indirect effect of intervention group on infant language production at the 6-month follow-up via ITSEA aggression/defiance scores at post-intervention was statistically significant. Of note, analyses were repeated using total utterances spoken during the observed infant-led play as the dependent variable, and results showed a similar pattern with a significant mediation path at the 6-month follow-up but not at the 3-month follow-up.

Discussion

The results of the current study provide initial support for the beneficial effect of a brief and home-based behavioral parenting intervention on language production for high-risk infants with elevated levels of behavior problems. Consistent with our hypothesis, findings revealed a significant and direct group effect on infant different (and total) utterances spoken during the observation of infant-led play at the 6-month follow-up, such that infants in the intervention group used significantly more different (and total) utterances than infants in the standard care group. This effect remained significant even after controlling for infant age at baseline, infant sex, maternal education level, language spoken at home, and baseline language production scores (both different and total utterances), which increased confidence that findings were not merely due to differences in infant language skills across the sample. However, findings revealed no significant group effect on infant different utterances at post-treatment or the 3-month follow-up.

One possible explanation for the significant intervention effect on infant language at the 6-month follow-up, but not at the post-intervention assessment or 3-month follow-up, is the age of the infants at the time of the different assessments. Specifically, infants were between 18- and 24-months-old at the 6-month follow-up assessment. While studies have provided support for word learning throughout early childhood (Rowe, Raudenbush, & Goldin-Meadow, 2012), the second year of life in particular has been consistently referred to as a time of continuous “vocabulary explosion,” where the rate of language acquisition accelerates dramatically (McMurray, 2007). Therefore, it is possible that the intervention produced an effect only at the 6-month follow-up when infants demonstrated the greatest rate of change in language production. Another possible explanation for the lack of significant effects immediately following the intervention and at the 3-month follow-up may be a delayed effect of the intervention on infant language. Given that the primary target of the intervention is to improve infant behavior and that the intervention led to improvements in later infant language at 3- and 6-month follow-ups through more immediate improvements in infant behavior, it is possible that the intervention does not positively affect infant language until changes in infant behavior occur. Nonetheless, the current study was an important first step in examining the effect of a behavioral parenting intervention on expressive language production in infancy.

In addition to examining the direct effect of the intervention on infant expressive language, we examined the indirect effect of the intervention on infant language production through changes in infant externalizing behavior problems. Consistent with our hypothesis, findings suggested that infants whose mothers reported larger decreases in externalizing behavior problems following the intervention displayed subsequently larger increases in different utterances spoken between the baseline and the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. These findings also were statistically significant after controlling for infant age at baseline, infant sex, maternal education level, language spoken at home, and baseline language production scores (both different and total utterances spoken). However, when analyses were repeated using total utterances, the mediating effect of infant behavior on infant total utterances was only significant at the 6-month follow-up but not at the 3-month follow-up. As noted above, it is possible that the infants’ limited expressive language abilities at the time of the 3-month follow-up may explain the lack of a significant indirect effect on total utterances spoken. Nevertheless, the finding that improvements in infant behavior led to subsequent increases in infant language production is consistent with previous research with toddlers (Brennan et al., 2012) and suggests that improvements in early behavior problems can have a positive influence on later language.

Taken together, the present study demonstrated the current parenting intervention led to improvements in infant language production, and that decreases in infant externalizing behavior problems are a potential mechanism by which the intervention led to improvements in infant language. To date, limited research has examined the relation between externalizing behavior problems and language impairment in infants, and no study examining interventions targeting early behavior problems assessed its direct effect on infant language. This study expands on these unexplored research questions, and the experimental design and multiple time points of the current study allowed for stronger inferences about the direction of the effect from infant behavior to language. Therefore, our results highlight a potential avenue for targeting two related problems, as the intervention led to improvements in both infant behavior and language production.

Limitations of the current study include a relatively small, predominantly ethnic minority sample. The reduced power due to the small sample size may explain the lack of significant intervention effects on language at post-intervention or the 3-month follow-up. Additionally, although the intervention and control groups did not differ on any demographic variables, the relatively small sample size limits power to detect possible differences between ethnic or racial groups, especially given that most families were Hispanic. Thus, it is possible that the current findings may not generalize to other racial minority families. Second, the sample consisted of infants with elevated levels of behavior problems, and findings may not generalize to typically developing infants. Third, data used in the current analyses were collected only from the mothers. Future research should examine the role of fathers, such as whether findings would be consistent when assessing infant expressive language during interactions with the father and behavior problems based on father report. Fourth, the control group was a standard care condition and did not allow us to control for expectancy effects. Therefore, future research should include an active comparison group, which would help make a stronger case for the efficacy of the intervention on infant language.

Fifth, the study relied on observations of infant language in a relatively brief period (i.e., 5 minutes) of observed infant-led play in the home, providing limited evidence for generalizability of improvements in infant vocalizations. Therefore, additional studies should examine changes in language during longer observation periods of time and in settings outside of the home and different from an infant-led play, as well as utilize standardized measures of expressive and receptive language, as in previous research on child language (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1995). Relatedly, the actual number of words produced during this short observation period was very low and highly skewed at each time point, and the intervention did not have an effect on words alone (as opposed to utterances, which included words and babbles), limiting the effect on the quality of language production. However, previous research has demonstrated the importance of infant babbling on the development of subsequent language (e.g., Vinham, Macken, Miller, Simmons, & Miller, 1985), suggesting the inclusion of babbles in our main outcome variable is important and relevant to the development of language. Nevertheless, although the present study evaluated infants 6 months following the intervention, future research should examine language outcomes at later time points (e.g., preschool years) when the child would likely produce more words and when functional outcomes (e.g., school readiness and performance) are more relevant. Finally, we did not consider other potential mechanisms by which the intervention may lead to improvements in infant language production. For example, mothers are taught to reflect infant vocalizations during the intervention, which has been shown to play a role in the improvement of child language (Garcia, Bagner, Pruden, & Nichols-Lopez, 2015), and thus should be examined in future research.

Despite these limitations, the current study extends the knowledge of language outcomes following behavioral parenting interventions for infants. Specifically, the findings provide support for the use of a behavioral parent-training intervention to improve infant language production. Furthermore, results suggest that externalizing behavior problems may be a key mechanism by which parenting interventions can affect infant expressive language and highlight the importance of targeting behavior in early intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH career development award (K23 MH085659) to the first author. We thank all participating families for their commitment to our research program.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alink LR, Mesman J, van Zeijl J, Stolk MN, Juffer F, Koot HM, van Ijzendoorn MH. The early childhood aggression curve: Development of physical aggression in 10-to 50-month-old children. Child Development. 2006;77:954–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00912.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Coxe S, Hungerford GM, Garcia N, Barroso NE, Hernandez J, Rosa-Olivares J. Behavioral parent training in infancy: A window of opportunity for high-risk families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0089-5. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Eyberg SM. Parent–child interaction therapy for disruptive behavior in children with mental retardation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:418–429. doi: 10.1080/15374410701448448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410701448448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Graziano PA. Barriers to success in parent training for young children with developmental delay the role of cumulative risk. Behavior Modification. 2013;37:356–377. doi: 10.1177/0145445512465307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145445512465307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Rodríguez GM, Blake CA, Rosa-Olivares J. Home-based preventive parenting intervention for at-risk infants and their families: An open trial. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20:334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.08.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Wilson B, Johnson CJ, Atkinson L, Young A, Adlaf E, Douglas L. Fourteen-year follow-up of speech/language-impaired and control children: Psychiatric outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:75–82. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner GJ, Nelson JR, Epstein MH. Language skills of children with EBD: A literature review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10:43–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/106342660201000105. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Nix Robert, L., Gest SD, Welsh JA, Greenberg MT, Gill S. Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI program. Child Development. 2008;79:1802–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan LM, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson M. Longitudinal predictors of school-age academic achievement: Unique contributions of toddler-age aggression, oppositionality, inattention, and hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1289–1300. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9639-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9639-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Bosson-Heenan J, Guyer AE, Horwitz SM. Are infant-toddler social-emotional and behavioral problems transient? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:849–858. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220849.48650.59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000220849.48650.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Irwin JR, Wachtel K, Cicchetti DV. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for Social-Emotional Problems and Delays in Competence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:143–155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Skuban EM, Horwitz SM. Prevalence of social-emotional and behavioral problems in a community sample of 1- and 2-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:811–819. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200107000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie EB, Beitchman J, Escobar M, Young A, Atkinson L, Johnson C, Douglas L. Early language impairment and young adult delinquent and aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:453–467. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030297.91759.74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/b:jacp.0000030297.91759.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann A, Jooss B, Rupp A, Feldhusen F, Pietz J, Philippi H. Parent based language intervention for 2-year-old children with specific expressive language delay: A randomised controlled trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2009;94:110–116. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.141572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.141572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ. ITSEA/BITSEA: Infant Toddler and Brief Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment Examiner's Manual. Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Davis NO. Assessment of young children's social-emotional development and psychopathology: Recent advances and recommendations for practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:109–134. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00316.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, Little TD. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:495–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1025449031360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1025449031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Messinger DS, Stone WL, Celimli S, Nahmias AS, Yoder P. A randomized controlled trial of Hanen’s ‘More Than Words’ in toddlers with early autism symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:741–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02395.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan R. Using the CHILDES Database. In: Hoff E, editor. Research methods in child language: A practical guide. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2011. pp. 272–284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781444344035. ch18. [Google Scholar]

- Crain-Thoreson C, Dale PS. Enhancing linguistic performance: Parents and teachers as book reading partners for children with language delays. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1999;19:28–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/027112149901900103. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, Varley J. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e17–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne G, Tremblay R, Boivin M, Laplante D, Perusse D. Physical aggression and expressive vocabulary in 19-month-old twins. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:261–273. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents' positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Intervening in children's lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E. Poverty and children with intellectual disabilities in the world's richer countries. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 2004;29:319–338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13668250400014491. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM. Tailoring and adapting parent–child interaction therapy for new populations. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005;28:197–201. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Jaccard J. Does maintenance treatment matter? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:355–366. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9842-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Bagner DM, Pruden SM, Nichols-Lopez K. Language production in children with and at risk for delay: Mediating role of parenting skills. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:814–825. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.900718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.900718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:313–333. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404044530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave AC, Sénéchal M. A book reading intervention with preschool children who have limited vocabularies: The benefits of regular reading and dialogic reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2000;15:75–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0885-2006(99)00038-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paulo H. Brookes Publishing; Baltimore, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hays JR, Reas DL, Shaw JB. Concurrent validity of the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence and the Kaufman brief intelligence test among psychiatric inpatients. Psychological Reports. 2002;90:355–359. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.355. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Irwin JR, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Heenan JMB, Mendoza J, Carter AS. Language delay in a community cohort of young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:932–940. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046889.27264.5E. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000046889.27264.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford GM, Garcia D, Bagner DM. Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) in a predominately Hispanic, low-income sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2015;37:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9478-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9478-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP, Cai X, Hancock TB, Foster EM. Teacher-reported behavior problems and language delays in boys and girls enrolled in Head Start. Behavioral Disorders. 2002:23–39. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23889147. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP, Hancock TB, Cai X, Foster EM, Hester PP. Parent-reported behavioral problems and language delays in boys and girls enrolled in Head Start classrooms. Behavioral Disorders. 2000;26:26–41. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23889147. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Wakschlag LS. More than the terrible twos: The nature and severity of behavior problems in clinic-referred preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:33–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1005118000977. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005118000977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. Responsive parenting: Establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:627–642. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Binns HJ, Christoffel KK, Gibbons RD. Psychiatric disorders with onset in the preschool years: I. Stability of diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1246–1254. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Gouze KR, Binns HJ, Keller J, Pate L. Predictors and correlates of completing behavioral parent training for the treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in pediatric primary care. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. 3rd ed Larence Erlbaum Associates; Mahway, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McMurray Bob. Defusing the childhood vocabulary explosion. Science. 2007;317:631–631. doi: 10.1126/science.1144073. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1144073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6:328–362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1094428103254673. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RDV, Sweeney L, Erickson DB, Touyz SW. Parent–child interaction therapy: A comparison of standard and abbreviated treatments for oppositional defiant preschoolers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:251–260. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Auinger P, Palmer R, Weitzman M. Do parenting and the home environment, maternal depression, neighborhood, and chronic poverty affect child behavioral problems differently in different racial-ethnic groups? Pediatrics. 2006;117:1329–1338. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MD, Brorson K. A comparative study between mean length of utterance in morphemes (MLUm) and mean length of utterance in words (MLUw) First Language. 2005;25:365–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142723705059114. [Google Scholar]

- Pons JI, Flores-Pabón L, Matías-Carrelo L, Rodríguez M, Rosario-Hernández E, Rodríguez JM, Yang J. Confiabilidad de la Escala de Inteligencia Wechsler para Adultos Versión III, Puerto Rico (EIWA-III) Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología. 2008;19:112–132. Retrieved from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org. [Google Scholar]

- Pons JI, Matías-Carrelo L, Rodríguez M, Rodríguez JM, Herrans LL, Jiménez ME, Yang J. Estudios de validez de la Escala de Inteligencia Wechsler para Adultos Versión III, Puerto Rico (EIWA-III) Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología. 2008;19:75–111. Retrieved from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi CH, Kaiser AP. Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2003;23:188–216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/02711214030230040201. [Google Scholar]

- Rausch JR, Maxwell SE, Kelley K. Analytic methods for questions pertaining to a randomized pretest, posttest, follow-up design. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:467–486. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviv T, Kessenich M, Morrison FJ. A mediational model of the association between socioeconomic status and three-year-old language abilities: The role of parenting factors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2004;19:528–547. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.10.007. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MY, Kaiser AP. Early intervention for toddlers with language delays: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135:686–693. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2134) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe ML, Raudenbush SW, Goldin-Meadow S. The pace of vocabulary growth helps predict later vocabulary skill. Child Development. 2012;83:508–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01710.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann EM, Foote RC, Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Algina J. Efficacy of parent–child interaction therapy: Interim report of a randomized trial with short-term maintenance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GA, Colpe L, Greenspan S. Measuring functional developmental delay in infants and young children: Prevalence rates from the NHIS-D. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2003;17:68–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00459.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. Inc . PASW Statistics for Windows. Version 18.0 Author; Chicago: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Zeijl J, Mesman J, Stolk MN, Alink LR, van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Koot HM. Terrible ones? Assessment of externalizing behaviors in infancy with the Child Behavior Checklist. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:801–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01616.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihman MM, Macken MA, Miller R, Simmons H, Miller J. From babbling to speech: A re-assessment of the continuity issue. Language. 1985;61:397–445. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/414151. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Scale of Intelligence. Third Edition Pychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. Pychological Corportation; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Ecala de Inteligencia Wechsler Para Adultos. Pearson; San Antonio, TX: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Crone DA, Zevenbergen AA, Schultz MD, Velting ON, Fischel JE. Outcomes of an Emergent Literacy Intervention from Head Start through Second Grade. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:261–272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.2.261. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Epstein JN, Angell AL, Payne AC, Crone DA, Fischel JE. Outcomes of an emergent literacy intervention in Head Start. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:542–555. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.86.4.542. [Google Scholar]

- Yew SGK, O’Kearney R. Emotional and behavioural outcomes later in childhood and adolescence for children with specific language impairments: Meta-analyses of controlled prospective studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:516–524. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen AA, Whitehurst GJ, Zevenbergen JA. Effects of a Shared-Reading Intervention on the Inclusion of Evaluative Devices in Narratives of Children from Low-Income Families. Journal of Applied Develop mental Psychology. 2003;24:1–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00021-2. [Google Scholar]