Abstract

Buprenorphine, an opioid that is a long-acting partial opiate agonist, is an efficacious treatment for opiate dependence that is growing in popularity. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that many patients will lapse within the first week of treatment, and that lapses are often associated with withdrawal-related or emotional distress. Recent research suggests that individuals’ reactions to this distress may represent an important treatment target. In the current study, we describe the development and outcomes from a preliminary pilot evaluation (N = 5) of a novel distress tolerance treatment for individuals initiating buprenorphine. This treatment incorporates exposure-based and acceptance-based treatment approaches that we have previously applied to the treatment of tobacco dependence. Results from this pilot study establish the feasibility and acceptability of this approach. We are now conducting a randomized controlled trial of this treatment that we hope will yield clinically significant findings and offer clinicians an efficacious behavioral treatment to complement the effects of buprenorphine.

Introduction

The nonmedical use of opiates, including prescription pain relievers and heroin, is a serious public health concern in the United States. In 2011, an estimated 2.2 million Americans met DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria for opiate abuse or dependence (SAMHSA, 2012). Buprenorphine, an opioid that is a long-acting partial opiate agonist, is an ambulatory treatment for opiate dependence that is growing in popularity, with over a million individuals in the U.S. treated since it became available in 2003 (Boothby & Doering, 2007). A sublingual dose is given daily and, once adjusted, produces neither subjective intoxication nor clinically detectable behavioral impairment (Fiellin & Barthwell, 2003). Offered as an office-based maintenance treatment alternative to methadone, an opiate agonist for which dosing is supervised at a clinic, buprenorphine has demonstrated efficacy in reducing opiate cravings, ameliorating withdrawal discomfort, and increasing periods of abstinence. In regard to treatment effectiveness (variously defined as reducing street crime, illicit drug use, HIV risk, or improving vocational development and psychological functioning), buprenorphine has been rigorously tested and shown to have positive outcomes (Mattick, Kimber, Breen, & Davoli, 2008).

Opiate Lapse After Initiating Buprenorphine Treatment

Patients who remain in opiate agonist treatment (OAT) for longer periods of time have better outcomes even after adjusting for comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions and severity of dependence (Baker, Kochan, Dixon, Wodak, & Heather, 1995; Caplehorn, Dalton, Cluff, & Petrenas, 1994; French, Zarkin, Hubbard, & Rachal, 1993; Gerstein, 2004; Hubbard et al., 1989; McLellan et al., 1996). Although there is no uniform time for keeping an individual patient in buprenorphine or methadone treatment to ensure long-term abstinence, some authors have found that outcomes improve across a variety of domains if patients continue treatment for at least one year (Friedmann, Lemon, Stein, Etheridge, & D'Aunno, 2001). However, buprenorphine treatment drop-out rates prior to one year are high, with observational studies reporting 50-65% retention rates at 6 months, and the great majority of attrition occurring during the first three months of treatment (Cunningham et al., 2008; Finch, Kamien, & Amass, 2007; Fudala et al., 2003; Lee, Grossman, DiRocco, & Gourevitch, 2009; Magura et al., 2007; Mintzer et al., 2007; Soeffing, Martin, Fingerhood, Jasinski, & Rastegar, 2009; Stein, Cioe, & Friedmann, 2005). Retention at 6-months is not significantly different from methadone treatment (Marsch, Bickel, Badger, & Jacobs, 2005).

Lapse to opiate use after initiation of buprenorphine is common and a strong predictor of poor treatment retention and return to chronic opiate use. Evidence from our group suggests that a significant proportion of persons initiating buprenorphine will lapse within the first week of treatment and are then at high risk for continuing opiate use during treatment, treatment drop-out, and relapse. We found that among 147 individuals who initiated buprenorphine, 59% had lapsed by the end of the first week and 78% of those who tested positive for opiates at week 1 had at least one additional positive opiate test during weeks 2-12, compared to only 24.3% of those who were opiate negative at week 1 (p < .001) (Stein et al., 2010). The incidence rate of treatment drop out during this 3-month study was about 1.65 times higher among those with a positive test at week one and 5.03 times higher (p =. 02) for those with a positive toxicology during the first four weeks. Among the 39% of participants dropping out of treatment, all of whom relapsed to illicit opiate use, 73% did so during the first eight weeks. In subsequent work, we have demonstrated that opiate craving, particularly during the first two weeks of buprenorphine treatment, similarly portends worse treatment outcome (Tsui, Anderson, Strong, & Stein, in press). Thus, convergent evidence indicates that early craving and lapses to opiate use are both frequent and highly predictive of continued opiate use during buprenorphine treatment and subsequent relapse (Stein, et al., 2005; Stein, et al., 2010).

Distress Tolerance

Theory and Research

Reasons for early attrition from buprenorphine treatment that have been identified include a desire to continue illicit drug use, social pressures due to a partner's or friend's drug use, and external barriers such as medication cost, especially for individuals without insurance or who lose their insurance, difficulty keeping medical appointments, and the requirement of frequent refills (Stein, et al., 2005). However, these factors do not account for all instances of relapse; risk for early illicit opiate lapse despite motivation for abstinence and pharmacologic treatment of acute withdrawal with buprenorphine implicates the substantial role that early events or situations play in increasing craving and motivating drug-seeking behavior (Goldstein & Volkow, 2002; Lubman, Yucel, & Pantelis, 2004; Robinson & Berridge, 2001). Indeed, early recovery situations and events that are associated with emotional distress, including the sensation of inadequate opiate substitution and prolonged withdrawal symptoms, continued exposure to environmental drug cues, loss of social relationships established through drug sharing, fear of treatment failure, stresses of everyday life (e.g. financial, familial), or concurrent mood disorder symptoms, reliably induce craving among treated opiate users (Hyman, Fox, Hong, Doebrick, & Sinha, 2007). Indeed, negative affect is well-established as a primary precipitant of early lapse and features prominently in current models of addiction maintenance and relapse (e.g., Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Hendershot, Witkiewitz, George, & Marlatt, 2011; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004), which have informed the development of behavioral treatments. Skills for the management and reduction of negative affect (e.g., stress management techniques, avoidance of triggers) are primary elements of these treatments. Meta-analyses indicate that cognitive-behavioral intervention for the treatment for substance use disorder is efficacious (Magill & Ray, 2009). However, recent trials evaluating cognitive-behavioral treatment specifically for patients taking buprenorphine have not shown significant benefit over physician management (Fiellin et al., 2013; Ling, Hillhouse, Ang, Jenkins, & Fahey, 2013), and a recent Cochrane review showed no significant benefit of adding a specific psychosocial treatment to OAT treatment as usual (Amato, Minozzi, Davoli, & Vecchi, 2011).

Research in the area of nicotine dependence has revealed that it is not solely the severity or intensity of distress, but also one's ability to tolerate both physical and psychological distress (i.e., distress tolerance) occurring in the context of withdrawal and early abstinence that predicts whether one succumbs to a lapse (Brandon et al., 2003; Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002; Brown et al., 2009; Quinn, Brandon, & Copeland, 1996). In these studies, distress tolerance was indexed as duration of persistence on psychological and physical challenge tasks that served as analogues for the types of stresses experienced during nicotine withdrawal. Psychological challenge tasks consisted of a mental arithmetic task requiring sustained attention in the presence of aversive auditory feedback for incorrect responses that produces elevated levels of stress (Paced Auditory Serial Addiction Task, PASAT, Diehr, Heaton, Miller, & Grant, 1998; Holdwick & Wingenfeld, 1999), and a frustrating mirror-tracing task in which participants trace the lines of geometric figures from the perspective of a mirror, such that their movements are reversed (Quinn, et al., 1996; Strong, 2003). Physical challenge tasks included inhaling carbon dioxide-enriched air (Lejuez, Forsyth, & Eifert, 1998) and breath-holding (Hajek, Belcher, & Stapleton, 1987).

Like nicotine withdrawal and craving, acute opiate withdrawal, which is required as part of standard clinical care in the hours prior to initiating buprenorphine, and craving in the days and weeks after the initiation of buprenorphine, produce uncomfortable interoceptive symptoms such as yawning, perspiration, eye tearing, nose runs, goose bumps, hot or cold shakes, bone and muscle aches, restlessness, nausea, cramps, and craving. Such experiential discomfort, to a greater or lesser degree, demands the use of distress tolerance skills in order to be successful in maintaining abstinence. Evidence suggests that opiate users are overly sensitive to the discomfort associated with anxiety symptoms (Lejuez, Paulson, Daughters, Bornovalova, & Zvolensky, 2006; Tull, Schulzinger, Schmidt, Zvolensky, & Lejuez, 2007). It seems likely then, that for those opiate users initiating buprenorphine treatment who have a low threshold for tolerating distress, and/or difficulty controlling, avoiding, or suppressing the private experience of distress, ongoing illicit drug use may serve as a way to manage internal states. These illicit substance-based efforts to avoid or escape distress are maintained by negatively reinforcing effects such as the reduction of urges or negative affect, even as euphoria is blocked by agonist properties of buprenorphine.

Supporting this hypothesis, we have recently extended findings from research on nicotine dependence to opiate dependence, demonstrating that among 48 individuals who initiated buprenorphine, shorter persistence time on the PASAT was related to significantly higher odds of a positive opiate toxicology over the 11-week assessment period, while controlling for levels of depressive symptoms, frequency of opiate use, and level of craving. The pattern of lower persistence times on the PASAT showed that the probability of opiate lapse was greatest soon after initiating buprenorphine, stabilized over subsequent weeks, and was highest among those with greater frequency of opiate use prior to treatment and among those with low persistence scores (Strong et al., 2011).

Implications for a Distress Tolerance Treatment

Given that inability or reduced ability to tolerate distress interferes with efforts to establish longer-term opiate-free behavior change (Strong et al., 2011), individuals who are initiating buprenorphine treatment may benefit from learning new skills or strategies to tolerate these withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and negative affect during early abstinence. We previously developed a distress tolerance-based treatment for smokers with a history of early smoking lapse that focused on skills to facilitate tolerance of nicotine withdrawal, negative affect, and other thoughts and feelings associated with smoking cessation, based on the notion that teaching smokers to minimize avoidance or efforts to escape this discomfort would strengthen their ability to persist at quitting smoking. Results were promising; in particular, this treatment seemed to facilitate recovery from lapses (Brown et al., 2008; Brown et al., in press). In the current manuscript, we present an adaptation of this distress tolerance treatment (DT) that was tailored for opiate dependent individuals initiating buprenorphine treatment. This treatment combines behavioral exposure to opiate craving with training in skills based in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Hayes, 2006) to promote maintenance of abstinence. We describe the methodology and preliminary outcome data for the first (pilot) phase of a two-phase study that is evaluating the efficacy of this DT treatment, including a detailed case study of one representative patient. This first phase included the process of treatment development and collecting pilot outcome data from two cohorts of 4 participants each, with the second phase consisting of an ongoing randomized clinical trial. Although we present outcomes from these pilot cohorts, this pilot phase was intended primarily to establish feasibility and acceptability (Leon, Davis, & Kraemer, 2011). Finally, we discuss the implications of this treatment approach.

Distress Tolerance Treatment for Buprenorphine Initiators

Program Overview

The DT treatment was developed and piloted in an iterative fashion. After treatment of the first cohort (n = 4), feedback was gathered from participants and therapists regarding coherence, understandability, and acceptability of the treatment manual. This feedback was used to make modifications to the manual prior to the second cohort. A similar process occurred during and after the second cohort (n = 4), with additional modifications made to finalize the treatment manual for use in the ongoing randomized trial.

The eight pilot participants were scheduled to receive seven, 50-min individual sessions of the DT treatment along with standard buprenorphine care (see Table 1). We discuss the components of standard buprenorphine care first and then describe DT, which was drawn from exposure-based and acceptance-based (ACT, Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999) treatment approaches and adapted from our DT smoking cessation treatment (Brown 2008). The DT program in the current study was designed to address two primary factors that influence ongoing opiate use despite buprenorphine treatment: learned habit and distress tolerance. Therapists, a masters level R.N. with a health promotion background and a post-doctoral fellow in clinical psychology, suggested to participants a core concept: that they could learn to manage discomfort with alternative strategies that would free them from using opiates as a means of maintaining a certain comfort level.

Standard Buprenorphine Care

Although buprenorphine has not been shown to have significantly better outcomes than methadone in studies in which the two treatments were compared directly, it has comparable efficacy(Connock et al., 2007; Mattick, Kimber, Breen, & Davoli, 2004). We selected buprenorphine rather than methadone in the current study for several reasons. As mentioned previously, buprenorphine has pharmacological features (lower risk of overdose) and administration advantages (can be prescribed in primary care offices) that have made it a popular option for persons interested in long-term agonist treatment. Most importantly, buprenorphine could be provided in an office research setting where our distress tolerance behavioral treatment could be tested, whereas methadone can only be delivered through Federally-regulated clinics which are all privately managed in our region, and would not have allowed for the testing of our protocol.

Since we expected most treatment drop-out to occur early in care during the first weeks to months, and because research funding limitation permitted only a finite treatment duration, we focused on a short maintenance phase, followed by tapering. The office-based buprenorphine treatment protocol included an induction day (Day 0), a 1-week dose stabilization phase, 12 weeks of buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and four additional weeks of buprenorphine taper. At the induction visit, under supervision, four milligrams of buprenorphine (with 1 mg of naloxone, provided as Suboxone tablets) was given sublingually to participants while they were experiencing mild-moderate opiate withdrawal as defined by a Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale score ranging from 13-24 (Wesson & Ling, 2003). The formulation that includes naloxone was used because it prevents snorting and injection and is thought to have lower diversion risk than Subutex which contains only buprenorphine. Additional buprenorphine was taken home for use later in the day (Lee, et al., 2009), with the first day total dose of 16 milligrams. The participant was scheduled to return two days later, and then given enough buprenorphine to last until the next visit five days later. Physician follow-up visits were scheduled for days 7 and 14 after induction and at weeks 4, 6, 8 and 12. At each physician visit, participants were given enough buprenorphine to use 16 mg per day until the subsequent appointment. After 12 weeks of maintenance treatment (Fiellin & Barthwell, 2003), the four-week buprenorphine taper (supervised withdrawal) began for participants unable to find a long-term provider. Participants planning to continue with another buprenorphine provider were maintained at 16mg, rather than tapering, until they transferred care at week 16.

At each visit beginning at induction, brief physician management (PM) counseling was provided by either of the two study clinicians. PM is a brief (10-15 minutes per session), manual-guided, medically-focused (Fiellin et al., 2002) intervention that approximates the medically-focused advice and brief counseling about medical issues typically provided by primary care practitioners. This level of physician counseling is consistent with the standard of care provided to buprenorphine patients and has been used in other office-based buprenorphine trials (Fiellin et al., 2006). The PM manual focused on reducing illicit drug use and adhering to buprenorphine treatment. Additionally, phone numbers for self-help groups (all off-site) were offered. Twelve-step involvement was recommended but not mandated.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes, et al., 1999) is designed to produce acceptance behaviors aimed at private events that have interfered with behaving consistently with one's life values, which are “ongoing patterns of activity that are actively constructed, dynamic, and evolving.” Unlike goals (e.g., “getting a degree”), which have defined end points, values (e.g., “education”) are never “completed and achieved in an absolute sense” and are defined as “directions” that guide behavior, rather than “destinations” (Wilson, Sandoz, & Kitchens, 2010, p.251). .Acceptance may be defined as actively engaging in the process of experiencing thoughts and feelings without attempting to avoid or change these experiences (Hayes, et al., 1999) as well as the behavior of approaching psychologically aversive internal stimuli while behaving adaptively (Gifford, 1994; Gifford & Hayes, 1997). A key component of the DT treatment in this study was ACT training to help participants acquire the skills needed to fully engage and persist in interoceptive exposure exercises while remaining non-avoidant of their internal reactions (e.g., craving, negative affect). Within this context, participants were taught the limitation of control strategies focused on avoiding discomfort and were made aware of their own tendencies to avoid or control emotional experience. Participants were encouraged to accept rather than try to suppress, modulate or distract themselves from their internal emotional experience and their cravings for opiates. Coupled with this focus were behavioral-based exercises to develop skills to manage environmental barriers to obtaining and maintaining an illicit opiate-free lifestyle. Overall, the ACT elements in the DT program were designed to highlight the benefits of accepting the time-limited discomfort of early abstinence, promote identification of personal values that would engender a willingness to persist in choosing not to use opiates when provoked by craving or negative affect, and convey skills promoting psychological flexibility to manage the early phase of abstinence and skillfully approach the goal of long-term abstinence.

Accumulating evidence indicates that ACT is an efficacious treatment approach across a variety of clinical problem areas, such as affective disorders (Zettle, 1984; Zettle & Hayes, 1986; Zettle & Raines, 1989) and anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorders, agoraphobia (Hayes, 1987; Hayes, Afari, McCurry, & Wilson, 1990), stress in the workplace (Bond & Bunce, 2000), and social anxiety (Block, 2002). Although a number of studies have shown promising results for smoking cessation (Bricker, Mann, Marek, Liu, & Peterson, 2010; Brown, et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2011; Brown, et al., in press; Gifford, 2004; Hernandez-Lopez, Luciano, Bricker, Roales-Nieto, & Montesinos, 2009), very limited research has examined the use of ACT for the treatment of other substance use disorders such as opiate dependence (Hayes et al., 2004; Stotts et al., 2012; Stotts, Masuda, & Wilson, 2009). Our study is the first to test the efficacy of ACT with buprenorphine-maintained patients.

Program Details

Treatment Population

We chose to focus on buprenorphine initiators because this growing population seeks care in primary care settings, which are increasingly involving behavioral health specialists and counselors (Butler et al., 2008), and offer the opportunity to begin a behavioral intervention prior to an induction date. Because there are no replicable, robust pre-treatment predictors of early opiate lapse and drop-out that would allow us to target a high-risk group, in the current pilot study we did not restrict enrollment based on prior treatment or drug use history. Therefore, some participants would not necessarily have lapsed or dropped-out even in the absence of DT. However, we believe that the treatment has the potential to benefit all recipients by promoting awareness of triggers, risks for illicit opiate lapse, and behavioral adaptation.

Structural Elements

The structure of the DT treatment included seven, 50-min manualized, individual sessions over a 31-day period, with sessions occurring 1-2 days prior to buprenorphine induction, on induction day, on the day after induction, and at day 5, 7, 14, and 28 after induction. Thus, we front-loaded the DT sessions such that the majority occurred prior to buprenorphine initiation and during the first weeks of treatment when the risk of lapse is highest (Stein, et al., 2010; Tsui, et al., in press). For pragmatic reasons, and to reduce participant burden, we also linked the DT sessions to physician visits and limited buprenorphine refill supply to the amount needed to reach the next scheduled visit using 16 mg per day. This strategy is common practice in clinical care, making the treatment schedule tested applicable to real world buprenorphine treatment. All DT sessions began with a review of material discussed in the previous session followed by the introduction of new concepts or exercises. Sessions also included homework assignments, which were discussed during the subsequent session. Homework assignments consisted primarily of reading and completing worksheets that reviewed session content, practicing coping strategies discussed in sessions, and engaging in valued activities committed to during sessions. To foster engagement and retention in the intervention, we encouraged participants to “think about,” “write down,” and “engage in committed action” related to the topics discussed in each session, to reinforce continued practice of the content we reviewed.

Treatment Rationale

Conveying an adequate rationale can affect both the credibility and expectancy of treatment (Horvath, 1990; Kazdin & Krouse, 1983), which in turn have been found to predict therapy outcomes (Borkovec & Costello, 1993; Chambless, Tran, & Glass, 1997; Collins & Hyer, 1986). Therefore, providing a coherent rationale for the DT treatment components was an important aspect of the intervention. Therapists provided the treatment rationale that there are three factors that maintain opiate use:

Physical addiction: Opiates in any form are addictive drugs. Your body becomes dependent on the drug so that when you try to quit, withdrawal symptoms occur. Common withdrawal symptoms include: irritability, anxiety, muscle aches, nausea, insomnia, and sweating.

Learned habit: A habit is a behavior pattern over-learned through months or years of repetition. By repeatedly responding to certain cues with a specific behavior (for example, when you feel uncomfortable, you use opiates), this behavior becomes an “automatic” response. After a while, you may not even notice that you are uncomfortable; you just know it's time to use.

Serves as a way to manage discomfort: People often use opiates as a way to manage their discomfort when they are feeling badly (e.g., sad, nervous, irritable, frustrated, angry, anxious, stressed, etc.) or are beginning to feel the effects of drug withdrawal (after a period of not using).

Participants are told that treatment would address all three of these components to assist them in maintaining abstinence: (1) physical addiction is addressed through the use of buprenorphine, which once stabilized, prevents withdrawal symptoms; (2) learned habit is addressed by helping participants to increase their awareness of patterns of events, situations and behaviors associated with use (“triggers”), and learning ways to respond to these situations without using, knowing that any euphoric effects of ongoing opiate use will be blocked by buprenorphine; (3) discomfort is managed by helping participants to explore the idea that regulating or controling comfort is an unworkable approach and that there is an alternative approach (i.e., acceptance).

Sessions 1 and 2 (Day -2 and Day 0 – Buprenorphine Induction)

Values Clarification

The primary goals of the first two therapy sessions were to develop a therapeutic alliance with participants, orient them to the treatment, and enhance their motivation, engagement, and commitment. These goals were accomplished through a discussion of the connection between the participant's life values, drug use, past quit attempts, and current transition to buprenorphine treatment and an illicit drug-free lifestyle. Therapists helped participants define specific behaviors they could engage in that reflect their values, such as spending time with family, helping children with homework, or spending more time with sober friends. Participants were asked to write these down on index cards, and refer back to them throughout the day and evening, as a reminder of what they were working towards. They were encouraged to write down additional values or expand on these values for homework, if they discovered other things that were important to them.

Psychoeducation about Triggers

Therapists next presented the theoretical model of drug use (physical addiction, learned habit, comfort regulation). With respect to learned habit, therapists introduced the concept of a trigger and the distinction between external (e.g., drug cues, interpersonal conflict) vs. internal (e.g., affective, cognitive, physiological) triggers. It was explained that a key component of the treatment would be the development of skills for managing triggers. After working together to identify triggers specific to the participant, each trigger was explored in terms of how it related to the participant's drug use and past quit attempts, and an in-depth functional assessment was conducted. Participants were encouraged to write down and categorize other triggers they identified after they left the session.

Exposure to Withdrawal Discomfort

The Induction day session (day 0) occurred while the participant was experiencing acute withdrawal symptoms, that is, before s/he received buprenorphine from the treating provider. Participants were told that despite beginning buprenorphine, some sensations of discomfort might continue. The session began with an “Acceptance” exercise, the purpose of which was to help the participant become more aware of internal sensations, and to practice acceptance of this discomfort. This exercise invited the participant to close his or her eyes, and quickly scan their body from head to toe, looking for uncomfortable sensations. The therapist guided the participant to notice where discomfort was the strongest, and focus on making room for it, without trying to fight or push it away. The exercise continued to allow the participant to identify other uncomfortable sensations, and repeat the process of practicing acceptance without trying to change or struggle with these feelings. During the debrief of the exercise, participants described and reflected upon their current thoughts, feelings, and sensations along with their efforts to allow discomfort to be present. Further discussion explored experiences during previous quit attempts and expectations of continued non-acute withdrawal or craving symptoms during the following 24-48 hours. This exercise and ensuing discussion served as initial exposure and set the stage for the therapist to introduce the concept of acceptance as a strategy for managing internal triggers. It was suggested to participants that efforts aimed at controlling discomfort actually end up making them feel worse. They were asked to consider whether the notion of trying to regulate or control comfort was an unworkable approach, referred to as creative hopelessness. A metaphor used to illustrate the concept of creative hopelessness was Passengers on the Bus, in which participants imagine themselves as a bus driver driving toward their values and their thoughts, feelings, and bodily states as scary “passengers” who are telling them what direction to drive and threatening them, although they've never actually been harmed by these “passengers.” If they stop the bus to deal with these passengers or they agree to do what the passengers say, they are acquiescing to the scary passengers (their thoughts, feelings and bodily states) rather than maintaining control (and “driving” toward their values).

Sessions 3, 4, and 5 (Days 1, 4, and 7)

Self-Management Skills

Traditionally, cognitive-behavioral therapies for substance use disorders have targeted changing or controlling triggers. Self-management techniques aimed at avoiding, altering, delaying or substituting triggers are frequently effective in helping individuals cope with external triggers, especially during the early stages of giving up illicit drugs. Participants were encouraged to practice these skills; however, therapists emphasized the use of self-management skills in response to external triggers only, as other strategies were to be used with internal triggers.

Acceptance and Exposure

Through exercises and metaphors, therapists illustrated how efforts to control or avoid internal experience may actually have the opposite effect, resulting in opiate use and difficulty abstaining. Participants were taught that self-management strategies were not effective responses to internal triggers; rather, acceptance should be practiced. For example, to illustrate the difficulty in controlling or avoiding thoughts, participants were asked what would happen if they were told “do not think about a jelly donut. Don't think about how soft and sweet it is, or how the sugar gets all over your fingers. Whatever you do, don't think about a jelly donut!” They were asked to consider how avoiding this thought would be similar to trying to avoid thoughts about drug use. Another metaphor compared acceptance to escaping quicksand: “The natural tendency is to try and get out. But almost everything you've learned about how to get out will make things worse; make you sink deeper. And as people start to sink, they often get panicky and start to flail about, only to sink deeper. The remedy is to lie still and make full contact with it, and not struggle.”

Participants were taught that there is not an intrinsic link between feelings and actions, and that the presence of aversive internal experiences, in and of themselves, does not constitute a threat. Participants were guided through exposure exercises designed to elicit difficult feelings, thoughts, or urges in the service of practicing new, effective behaviors or responses that are more consistent with their values. For example, participants practiced noticing thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judgment, and imagined placing each on a leaf and watching it slowly float away. Participants also practiced labeling their thoughts out loud without judgment or attachment, “I'm having the thought that....” to help them recognize and distinguish uncomfortable thoughts from reality or something that needs to be acted on. In addition, participants practiced a series of meditations that asked them to imagine themselves in different future situations, free from their addicted opiate, and how they would feel about themselves and the life they were leading. Therapists emphasized that acceptance was an active rather than a passive process, and included changing how one behaved in response to these internal experiences (i.e., behavior consistent with values rather than avoidance). An example of acceptance as an active process was that of a marathon runner “carrying” their discomfort with them on their shoulders or backs as they focused on the values-consistent behavior of making it to the finish line.

Willingness

Willingness is an extension of the concept of acceptance. Willingness refers to acceptance without time or intensity-type limits (Hayes, et al., 1999). Willingness was introduced using the Two Scales metaphor (Hayes, et al., 1999) – the two scales referring to 1) intensity of discomfort and 2) degree of willingness to experience discomfort without trying to change, avoid, or escape it. It was suggested to participants that although they may try to control the discomfort scale, willingness is the only scale they actually have control over and therefore they should shift their focus to keeping the willingness scale set to maximum (willingness). As part of this component, participants explored their tendency to place limits on acceptance; for example, by making deals or bargains with themselves that they would be willing to endure discomfort only to a certain point, beyond which time they would lapse to drug use (e.g., “If I have a really bad day, then it's ok to use.”). A metaphor to illustrate the concept of willingness was the “child in a candy store” metaphor in which participants’ bargains with their discomfort were compared to parents’ bargains with how long they would be willing to let their children tantrum for candy before they would give in and buy it.

Defusion

Defusion involves decreasing the believability of thoughts by viewing thoughts as what they are (cognitive constructs that do not have to be reacted to or believed) and not as what they appear to be (e.g., reality, commands to act in ways consistent with the thought). Similar to exposure and acceptance, defusion functions to facilitate new associations to cognitive triggers. Participants engaged in a series of exercises designed to identify and defuse cognitive triggers, with particular emphasis on rationalizations for drug use. For example, participants practiced labeling their thoughts as such (“I'm having the thought that I want to use”) in order to recontextualize them as just thoughts rather than a cause with a necessary effect (i.e., a cause of their use).

Values

Participants were asked to identify and explore their values, through a meditation exercise, and write them down on index cards so that they could refer back to them frequently, especially during times of discomfort and craving. They also participated in additional experiential exercises designed to facilitate values clarification and engagement in values-consistent behavior. For example, they imagined themselves in 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and a year as drug-free. We also used an exercise that was adapted from a eulogy exercise outlined in Hayes et al. (1999). In this exercise, participants imagined being contacted 10 years in the future by a publisher who wanted to write their life story, including interviews with the people closest to them. They envisioned what they would ideally want these people to say about how they lived their life.

Sessions 6 and 7 (Days 14 and 28)

These sessions were intended to provide additional opportunities for exposure and practice of acceptance, willingness, and defusion, reinforce commitment to effective changes, provide social support, plan for relapse prevention including responding to slips as learning experiences, and preparation for buprenorphine taper.

Committed Action

Participants discuss values-related goals and barriers, and their relation to maintaining adherence to the buprenorphine treatment protocol and committed action. Committed action is discussed as a process, utilizing the example of being married or being a parent – each day re-committing. Participants are encouraged to make a verbal commitment to continue the process of being straight and sober and living values-consistent lives. The use of positive, alternative behavioral reinforcers, such as exercise, meditation or engaging in a hobby, and use of social support (e.g., self-help meetings) was highlighted.

Self-as-Context

Participants engaged in experiential exercises that help them make contact with a safe and consistent perspective from which to observe and accept all changing inner experiences. Participants were taught to identify when they were becoming overwhelmed and experiential exercises were used to help participants see themselves as the context in which they experience events (e.g., cravings, thoughts, feelings, etc.) rather than the events themselves.

Process of Revising the Treatment Manual

Changes to Values Clarification exercises

In the original version of the treatment manual, values were initially explored in Session 1 by reviewing participants’ responses to a questionnaire in which they ranked values by importance and then again in Session 5 during the life story exercise. However, early piloting revealed that the timing between these 2 exercises was too long, and the content insufficient to foster continued review of values as a central theme and driving force. Therefore, we added a meditation exercise to Session 1, in which we asked participants to look deep into their heart and reflect upon what motivated them to invest their time and effort to come for treatment. This meditation was followed by a more extensive discussion of their values in major life areas, such as relationships, career/education, leisure activities, mind/body/spirit and daily responsibilities. After this discussion, we invited participants to write down their values on index cards, and we encouraged them to review these throughout the coming days, especially at times when they were experiencing discomfort. Participants were also asked to bring these cards back to each session for additional review. These values cards became an integral reminder of what the participant was working towards and were referred to in each subsequent session. In addition, we moved the life story exercise to Session 4, to revisit their values in the broader context of their life, beyond how they relate to their efforts to give up opiates.

Changes to Exposure Exercises

Early versions of the protocol used various activities to promote distress exposure, but didn't clearly convey the basic premise that comfort regulation may be the problem (i.e., creative hopelessness). We therefore revised the protocol and removed exposure exercises that didn't seem to offer participants new insights, such as repeated breath holding. Instead, we included the Man in the Hole metaphor (Hayes, et al., 1999), which compares efforts to control discomfort to trying to dig one's way out of a hole, at the conclusion of Session 1, as a way to highlight the futility of ongoing efforts to manage discomfort. This metaphor resonated well with participants, and it thus served as an ongoing reminder that making efforts to manage internal triggers is an unworkable solution. To build upon this premise, we incorporated similar metaphors into subsequent sessions, including as described above Passengers on the Bus, Two Scales (Willingness) (Hayes, et al., 1999), and Quicksand (Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007), which were frequently referenced by participants as metaphors they thought about during times of distress.

Other Changes

To reinforce participants’ ability to develop and strengthen acceptance and commitment skills, we modified the protocol to include follow-up questions after meditation and metaphor exercises to explore possible situations in which the participant might use these activities in between sessions. At the close of each session, we also incorporated the question “What's one thing you can take away from this lesson that might be helpful to you?” to better understand which concepts, metaphors and skills participants found most relevant and to help them consolidate plans for moving forward. Lastly, we ended each session by encouraging participants to review their values cards, complete worksheets that we started during the session, and commit to at least one action that would help them get one step closer to living a life that is consistent with their expressed values and goals.

Pilot Study Outcomes

Participants

Eight (n = 8) participants were recruited from the Providence, RI area via advertisements (newspaper, bus) and referrals from local clinicians. Inclusion criteria were age 18-65, initiating buprenorphine treatment, and planning to remain on buprenorphine for at least 3 months. Individuals were excluded for current participation in methadone maintenance treatment; 15 or more days of benzodiazepine or cocaine use in the last month; daily alcohol use or binges weekly or more; medically necessary opiate treatment for chronic pain; surgery in the next 3 months; current suicidality; neuropsychological dysfunction; justice system involvement that might interfere with participation; bipolar or psychotic disorder; or pregnancy.

Two of the 8 participants did not initiate buprenorphine nor attend any complete DT sessions (1 attended a partial session) and another participant had a negative opiate toxicology screen at baseline and was therefore determined ineligible, leaving 5 who initiated buprenorphine and DT treatment. Therefore, we present outcomes of these 5 participants (4 males and 1 female). Two were non-Hispanic white, 2 were Hispanic, and 1 was African-American. Their mean age was 40.40 (SD = 9.74) and they had used opiates (excluding buprenorphine or methadone) on a mean of 24.2 of the last 30 days. Two had a history of injection opiate use. Three had been prescribed buprenorphine in the past. One participant completed three DT sessions and the others (n = 4) completed all seven DT sessions.

Assessment Schedule

Assessments were completed at baseline (prior to buprenorphine initiation) and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16-weeks following initiation of buprenorphine. Three of the 5 participants completed all follow-ups; 1 was lost following the 1-week assessment, and 1 was lost following the 4-week assessment.

Primary Outcomes

Toxicology

At 1-week follow-up, 4 of the 5 participants had negative urine toxicology for opiate use. The participant who tested positive continued to test positive through 16 weeks. Of the 4 who tested negative at 1-week, 2 continued to test negative at all additional assessments they completed, 1 did not complete any additional assessments after week 1, and 1 tested positive from weeks 2-12. but negative at week 16.

Self-reported drug use

The Timeline Followback (TLFB) method (Fals-Stewart, O'Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin, & Rutigliano, 2000) was used at each assessment to assess self-reported drug consumption since the previous assessment. Days of opiate use per month (not including buprenorphine or methadone) decreased from a mean of 24.20 (SD = 6.57) at baseline to 2.25 (SD = 2.87) at 4 weeks, .33 (SD = .58) at 8 weeks, 2.00 (SD = 3.46) at 12 weeks., and 1.67 (SD = 2.89) at 16 weeks. A fixed effects regression analysis of this data revealed a significant overall decrease in opiate use during the follow-up period (F(4,9) = 19.07, p = .002). Becker's Standardized Mean Change (SMC) {Becker, 1988}, which represents standardized reduction over time [(baseline mean – follow-up mean)/baseline standard deviation], was 3.34, 3.63, 3.38, and 3.43 at 4-, 8-, 12-, and 16-weeks, respectively.

Treatment Effectiveness Assessment (TEA)

(Ling, Farabee, Liepa, & Wu, 2012). The TEA is a 4-item measure of improvement in substance use, health, lifestyle, and community as a result of treatment. For the current study, participants rated how they were currently doing in these areas at each assessment on a scale from 1 (poor) to 10 (great). Overall, mean scores showed an upward trend over time, from 5.60 (SD = 1.59) at baseline to 6.67 (SD = 3.02) at 16 weeks.

Process Measures Outcomes

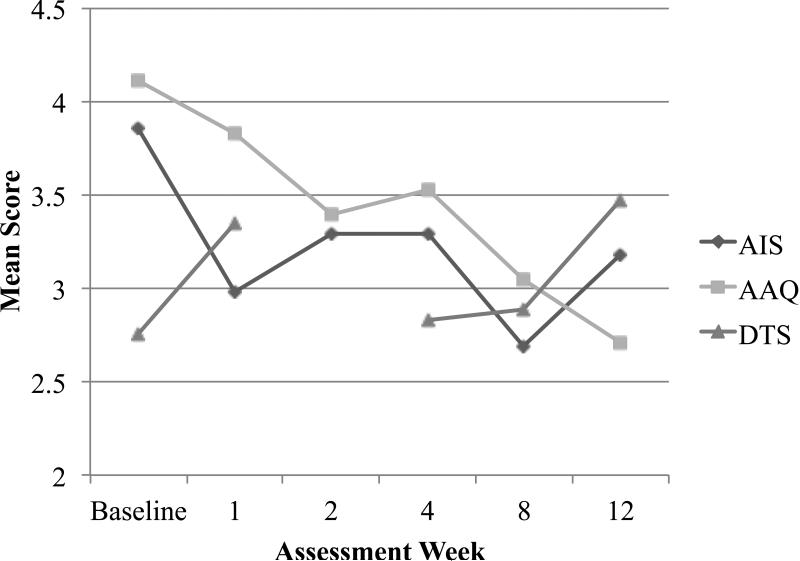

Several measures relevant to distress tolerance were administered. For each measure, participants’ scores were calculated as their mean response to all items. The overall pattern of results indicated decreasing experiential avoidance and increasing distress tolerance over time (see Figure 1). Specific patterns for each measure are described below.

Figure 1.

Mean Scores on Process Measures.

AIS = Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale, AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire. DTS = Distress Tolerance Scale.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II)

We used the newest version of this measure (7-items), which assesses general psychological acceptance, emotional willingness, and tendency to engage in experiential avoidance (Bond et al., 2011). Mean scores consistently decreased over time, indicating increasing acceptance and decreased avoidance, from 4.11 (SD = 1.14) at baseline to 2.71 (SD = .20) at 12 weeks (SMC = 1.23) (see Figure 1).

Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS)

This 13-item scale assessed experiential avoidance specific to opiate use; it was adapted from the original AIS developed to assess experiential avoidance specific to cigarette smoking (Gifford, Antonuccio, Kohlenberg, Hayes, & Piasecki, 2002). Participants rated, on 5-point scales, the extent to which they attempt to avoid or control internal stimuli (thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations) as a means of abstaining from opiate use and the extent to which the presence of these stimuli lead them to use, with higher mean scores indicating greater avoidance/inflexbility. Mean scores showed an overall decrease over time, indicating decreased avoidance and inflexibility, from 3.86 (SD = .63) at baseline to 3.18 (SD = .24) at 12 weeks (SMC = 1.08), with a low of 2.69 (SD = .20) at 8 weeks (see Figure 1).

Distress Tolerance Scale

The 15-item Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS) assessed the extent to which participants believed they could experience and withstand distressing emotional states (Simons & Gaher, 2005). Items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale; total score was calculated as the mean score on all items with higher scores indicating greater distress tolerance. The DTS was not administered at week 2. Overall, scores tended to increase over time, from 2.75 (SD = .70) at baseline to 3.47 (SD = .69) at 12 weeks (SMC = 1.03) (see Figure 1).

Example Case Study

M.M. was a 31-year-old, unemployed, single male. He reported a history of opiate use beginning in his early 20s, subsequent to injuries he sustained in a motor vehicle accident. M.M. has suffered from chronic pain ever since. Initially, this pain was managed through prescription use of opiates. Because of worsening pain and what he described as losing his “drive to live,” M.M. began to abuse his prescription opiates and then transitioned to using heroin intra-nasally. He attributed his heroin use primarily to his chronic pain, plus feelings of anxiety and depression due to the accident having long-term effects on his ability to function. At treatment initiation, he had been unemployed for multiple years and was financially dependent on his family for food and housing.

In the first session, M.M. described his previous profession as physically demanding, noting that work activities worsened his pain and increased his “need” for using heroin to manage his pain. Over time, M.M. realized that he could not sustain regular work due to the pain it caused. He described feeling hopeless about his career because he could not sustain the physical activity it required, plus, he did not enjoy the work. During the values exploration meditation in the first session, M.M. highlighted a desire (1) to regain his “drive” to take control of his life; (2) to be independent; and, (3) to develop good relationships in his life. M.M. explained that his family was generally supportive of his struggles with pain and addiction, but that he tended to isolate himself from them in favor of using heroin. Moreover, he had not had a girlfriend in 2 years and had stopped socializing with friends due to feelings of shame about his addiction as well as a lack of self-confidence.

At the second session, M.M. discussed his previous attempts to quit using heroin. He attempted to quit “cold turkey” a few times without any success. For 2-3 months, he was enrolled in a buprenorphine outpatient treatment program. He described the treatment as “inadequate” as the medication was helpful in managing the physical opiate dependence but did not address his psychological barriers to sobriety. M.M. particularly enjoyed the meditation in this session, which focused on developing skills to accept unpleasant thoughts, feelings, and sensations. As per the treatment protocol, M.M. was in acute withdrawal during this session prior to receipt of his induction dose of buprenorphine, complaining of nausea, chills, and feelings of anxiety. He recognized acceptance as a viable alternative to trying to alter or change his feelings, particularly in light of his chronic pain, which would probably never fully remit.

M.M. described a variety of strategies he used to behaviorally manage external triggers. He reported that his heroin dealer contacted him and M.M. did not answer the telephone. In the third session, he developed a plan to confront his dealer about his commitment to stop using heroin to minimize the risk of being “tempted” to use again. He altered his living space by rearranging furniture in his home so that the desk he typically used heroin on, which was in his bedroom, was moved into a communal living space in his home. Additionally, M.M. reported “staying busy” by spending time with his family and reconnecting with a friend to minimize his risk for use. He particularly appreciated the discussion of willingness in the third session. M.M. acknowledged that his focus was on discomfort (e.g., pain, feeling depressed about his life, etc.) and that willingness was a novel concept that could help him regain control of his life regardless of his discomfort.

In the fourth session, M.M. reported using the treatment technique of, “I'm having the thought that...” between sessions when thinking about his relationship with his father. M.M. recognized how the thought, “Things will never change with my father,” undermined his willingness to make efforts to improve the relationship. He explained this technique helped him realize that his thoughts are not a reality and that they do not have to dictate his behaviors. In session four, the quicksand metaphor is used to demonstrate how struggling with thoughts, feelings, and sensations is futile and likely worsens the situation, much like struggling to free oneself from quicksand. M.M. related this metaphor to his struggles with pain and suggested he should “increase the surface area” upon which he experiences the pain. M.M. had difficulty generating positive qualities about himself during the values exploration exercise. He described significant shame and guilt about how he allowed heroin to “take over” his life. He noted that these feelings lead to recent “anxieties” about reconnecting with friends. M.M. was encouraged to acknowledge that he has thoughts that his friends will judge him and think badly of him, without allowing these thoughts to limit his willingness to reconnect with people. M.M. continued to maintain his sobriety through session five, in which he described continuing to apply acceptance-based skills to maintaining his sobriety. Additionally, he continued to develop behavioral plans to reduce external triggers. For example, each morning, M.M. would use heroin at his desk in his bedroom as soon as he woke up. To develop a new morning routine, M.M. decided to go for walks, which also helped manage his pain.

M.M.'s biggest challenge came prior to session six. He spent the previous weekend helping a family member with yard work. M.M. described being in significant pain secondary to this physical activity, including being bed-ridden for the entire day following the work. He explained that this experience made his physical limitations very clear and without heroin to “mask the pain,” he realized that he was much less able to be physically active than he thought. Despite this experience, M.M. did not revert to using opiates to control his pain. He was able to accept his pain and thoughts that he was much more physically limited than other men his age, while focusing on moving forward in his life. He described “taking pain off a pedestal,” when discussing the Tin Can Monster metaphor. M.M. agreed that “pain” had become this very intimidating, very controlling “thing” in this life and that although unpleasant, was not something to fear or to let control his life.

At the final session, M.M. maintained his treatment gains and had not used heroin since enrolling in the treatment program. He reported some urges to use and described managing them via acceptance. M.M. was encouraged to continue to use acceptance-based skills to cope with internal experiences, while continuing to be creative about ways to manage external triggers. It was acknowledged that his chronic pain and wavering self-confidence were likely to be his biggest barriers to abstinence, but that he had a useful variety of strategies to cope with these challenges.

Discussion

In the current study, we developed and conducted a preliminary pilot evaluation of a novel distress tolerance (DT) treatment for opiate dependent individuals initiating buprenorphine to assist them in maintaining abstinence from and preventing relapse to opiates. This treatment incorporates elements from exposure-based and acceptance-based treatment approaches. We accomplished our primary goal of establishing the feasibility and acceptability of this approach (Leon, et al., 2011). Although the sample size (N = 5) was too small to conduct formal statistical analysis or evaluate the efficacy of this new DT treatment, the results showed promise in revealing large decreases in opiate use among participants. Furthermore, examination of participants’ scores on self-report measures of distress tolerance indicates a general pattern of increasing distress tolerance and decreasing avoidance over time, consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms of treatment. We are currently engaged in completing a larger randomized trial and look forward to the opportunity to conduct formal analyses of outcomes and treatment processes.

During the course of this pilot study, we made modifications to the treatment protocol, which we believe were important in assisting patients to fully engage with the treatment content. One very important modification was intended to get patients in touch with the values in their life that might drive their desire to function without the use of opiates. Meditation and experiential exercises were either moved from later sessions to earlier ones, or added to the protocol to highlight and reinforce values in an ongoing way. Furthermore, we invited participants to write down their values on index cards, refer to them often throughout the day, especially when experiencing discomfort, and bring them back to each counseling session, as a constant reminder of what they were working towards. Additional revisions to the protocol included re-examining the exposure exercises, and refining our selections to the exercises that seemed to best reinforce the notion of creative hopelessness. Lastly, we added exploratory questions after meditation exercises and metaphors to help participants identify how they might use these in their daily life to reinforce their ability to develop and strengthen acceptance and commitment skills.

In light of the public health significance of opiate abuse and dependence in the United States (SAMHSA, 2012), and the growing popularity of buprenorphine as an ambulatory treatment for opiate dependence (Boothby & Doering, 2007), the current work is timely and important. It is clear that patients who remain on opiate agonist treatments for longer periods of time have better outcomes (Gerstein, 2004), and yet drop out rates are high, particularly during the first three months of treatment (Stein, Cioe, & Friedmann, 2005). Lapse to opiate use after initiation of buprenorphine is common and a strong predictor of poor treatment retention and return to chronic opiate use. Indeed, we have found that early lapse, within the first week of initiating buprenorphine treatment, is particularly likely to be associated with treatment dropout and relapse to opiate use (Stein, et al., 2010). Given that inability or reduced ability to tolerate distress of discomfort interferes with efforts to establish longer-term opiate-free behavior change (Strong, et al., 2011), individuals who are initiating buprenorphine treatment may benefit from learning new skills or strategies to tolerate the discomfort of withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and negative affect during early abstinence.

The distress tolerance treatment described here is intended to provide these skills to opiate dependent individuals initiating buprenorphine treatment. We acknowledge that relapse rates for abstinence-oriented approaches for the treatment of opiate dependence such as our DT treatment remain high and to date, only a minority can be expected to achieve long-term abstinence. Nevertheless, given the positive preliminary indications from this pilot work, we are hopeful that the ongoing RCT will yield clinically significant findings, and will ultimately offer clinicians an efficacious behavioral treatment that, when used in conjunction with buprenorphine treatment, will significantly complement its effects by reducing instances of early lapse and subsequent relapse to opiate use.

Acknowledgements

Study medication was provided by Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals who had no role in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, but did review the report for scientific accuracy.

This study was supported by NIDA grant R34DA032767. Dr. Stein is a recipient of NIDA Award K24DA000512. Study medication was provided by Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals who had no role in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, but did review the report for scientific accuracy.

References

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011:CD004147. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Kochan N, Dixon J, Wodak A, Heather N. HIV risk-taking behaviour among injecting drug users currently, previously and never enrolled in methadone treatment. Addiction. 1995;90:545–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9045458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JA. Acceptance or change of private experiences: A comparative analysis in college students with public speaking anxiety. University at Albany, State University of New York; Albany, NY.: 2002. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Bunce D. Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:156–163. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby LA, Doering PL. Buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid dependence. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2007;64:266–272. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:611–619. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Herzog TA, Juliano LM, Irvin JE, Lazev AB, Simmons VN. Pretreatment task persistence predicts smoking cessation outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:448–456. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Mann SL, Marek PM, Liu J, Peterson AV. Telephone-delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for adult smoking cessation: a feasibility study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:454–458. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Carpenter LL, Price LH. A prospective examination of distress tolerance and early smoking lapse in adult self-quitters. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Gifford EV. Distress tolerance treatment for early-lapse smokers: rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2008;32:302–332. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Zvolensky M, Gifford EV, Hayes SC. Efficacy of distress tolerance/ACT treatment vs. standard behavioral treatment for early lapse smokers.. Annual Meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine; Washington, DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Reed KMP, Bloom EL, Minami H, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Hayes SC. Development and preliminary randomized controlled trial of a distress tolerance treatment for smokers with a history of early lapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt093. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, Kathol RG, Fu SS, Hagedorn H, Wilt TJ. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. 2008:1–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplehorn JR, Dalton MS, Cluff MC, Petrenas AM. Retention in methadone maintenance and heroin addicts' risk of death. Addiction. 1994;89:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Tran GQ, Glass CR. Predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:221–240. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J, Hyer L. Treatment expectancy among psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1986;42:562–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198607)42:4<562::aid-jclp2270420404>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, Frew E, Liu Z, Taylor RJ, Taylor RS. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment. 2007;11:1–171. iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Giovanniello A, Sacajiu G, Whitley S, Mund P, Beil R, Sohler N. Buprenorphine treatment in an urban community health center: what to expect. Family Medicine. 2008;40:500–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr MC, Heaton RK, Miller W, Grant I. The paced auditory serial addition task (PASAT): Norms for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1998;5:375–387. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Cutter CJ, Moore BA, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. The American journal of medicine. 2013;126:74, e11–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Barthwell AG. Guideline development for office-based pharmacotherapies for opioid dependence. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2003;22:109–120. doi: 10.1300/j069v22n04_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:365–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Pakes JP, O'Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Treatment of heroin dependence with buprenorphine in primary care. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:231–241. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JW, Kamien JB, Amass L. Two year experience with buprenorphinenaloxone (Suboxone) for maintenance treatment of opiod dependence within a private practice setting. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2007;1:104–110. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31809b5df2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Zarkin GA, Hubbard RL, Rachal JV. The effects of time in drug abuse treatment and employment on posttreatment drug use and criminal activity. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19:19–33. doi: 10.3109/00952999309002663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Lemon SC, Stein MD, Etheridge RM, D'Aunno TA. Linkage to medical services in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study. Medical Care. 2001;39:284–295. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudala P, Bridge T, Herbert S, Williford W, Chiang C, Jones K, Group, B. N. C. S. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:949–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein DR. Outcome Research: Drug abuse. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, editors. The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. 3 ed. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D. C.: 2004. pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV. Setting a course for behavior change: The verbal context of acceptance. In: Hayes SC, Jacobson NS, Follette VM, Dougher MJ, editors. Acceptance and change: Content and context in psychotherapy. Context Press; Reno, NV: 1994. pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Antonuccio DO, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Piasecki MM. Combining Bupropion SR with acceptance-based behavioral therapy for smoking cessation: Preliminary results from a randomized controlled trial.. Paper presented at the Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Reno, NV.. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Hayes SC. Discrimination training and the function of acceptance.. Paper presented at the Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis; Chicago, IL.. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MM, Rasmussen- Hall ML, Palm KM. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:689–706. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Belcher M, Stapleton J. Breath-holding endurance as a predictor of success in smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1987;12:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, Wilson K, Gifford E, Bissett R, Piasecki M, Batten S, Gregg J. A preliminary trial of twelve-step facilitation and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance-abusing methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:667–688. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC. A contextual approach to therapeutic change. In: Jacobson N, editor. Psychotherapists in clinical practice. Guilford Press; New York: 1987. pp. 327–387. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC. The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire - II. 2006 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Afari N, McCurry SM, Wilson KG. The efficacy of comprehensive distancing in the treatment of agoraphobia.. Paper presented at the Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis; Nashville, TN.. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. The Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2011;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Lopez M, Luciano MC, Bricker JB, Roales-Nieto JG, Montesinos F. Acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation: a preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdwick DJ, Jr., Wingenfeld SA. The subjective experience of PASAT testing. Does the PASAT induce negative mood? Archives of clinical neuropsychology : the official journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists. 1999;14:273–284. doi: 10.1093/arclin/14.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P. Treatment expectancy as a function of the amount of information presented in therapeutic rationales. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;46:636–642. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199009)46:5<636::aid-jclp2270460516>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, Harwood HJ, Cavanaugh ER, Ginzburg HM. Drug abuse treatment: a national study of effectiveness. The University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Fox H, Hong KI, Doebrick C, Sinha R. Stress and drug-cue-induced craving in opioid-dependent individuals in naltrexone treatment. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:134–143. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Krouse R. The impact of variations in treatment rationales on expectancies for therapeutic change. Behavior Therapy. 1983;14:657–671. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Grossman E, DiRocco D, Gourevitch MN. Home buprenorphine/naloxone induction in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:226–232. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0866-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Forsyth JP, Eifert GH. Devices and methods for administering carbon dioxide-enriched air in experimental and clinical settings. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1998;29:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(98)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Paulson A, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Zvolensky MJ. The association between heroin use and anxiety sensitivity among inner-city individuals in residential drug use treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Farabee D, Liepa D, Wu LT. The Treatment Effectiveness Assessment (TEA): an efficient, patient-centered instrument for evaluating progress in recovery from addiction. Substance abuse and rehabilitation. 2012;3:129–136. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S38902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Hillhouse M, Ang A, Jenkins J, Fahey J. Comparison of behavioral treatment conditions in buprenorphine maintenance. Addiction. 2013;108:1788–1798. doi: 10.1111/add.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Addiction, a condition of compulsive behaviour? Neuroimaging and neuropsychological evidence of inhibitory dysregulation. Addiction. 2004;99:1491–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Hayes SC, Walser R. Learning acceptance and commitment therapy: A Skills Training Manual for Therapists. New Harbinger Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2009;70:516–527. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Lee SJ, Salsitz EA, Kolodny A, Whitley SD, Taubes T, Rosenblum A. Outcomes of buprenorphine maintenance in office-based practice. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2007;26:13–23. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, Jacobs EA. Buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence: the relative efficacy of daily, twice and thrice weekly dosing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004:CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008:CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Woody GE, Metzger D, McKay J, Durrell J, Alterman AI, O'Brien CP. Evaluating the effectiveness of addiction treatments: reasonable expectations, appropriate comparisons. Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74:51–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzer IL, Eisenberg M, Terra M, MacVane C, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Treating opioid addiction with buprenorphine-naloxone in community-based primary care settings. Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5:146–150. doi: 10.1370/afm.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EP, Brandon TH, Copeland AL. Is task persistence related to smoking and substance abuse? The application of learned industriousness theory to addictive behaviors. Experiemental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction. 2001;96:103–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug use and Health: Summary of national findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2012. NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The distress tolerance scale: development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Soeffing JM, Martin LD, Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR, Rastegar DA. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment in a primary care setting: outcomes at 1 year. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Cioe P, Friedmann PD. Buprenorphine retention in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:1038–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Herman DS, Kettavong M, Cioe PA, Friedmann PD, Tellioglu T, Anderson BJ. Antidepressant treatment does not improve buprenorphine retention among opioid-dependent persons. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Green C, Masuda A, Grabowski J, Wilson K, Northrup TF, Schmitz JM. A stage I pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for methadone detoxification. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]