Abstract

Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE ε4) is the most prevalent genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD). Targeted replacement mice that express either APOE ε4 or its AD benign isoform, APOE ε3, are used extensively in behavioral, biochemical, and physiological studies directed at assessing the phenotypic effects of APOE ε4 and at unraveling the mechanisms underlying them. Such experiments often involve pursuing biochemical and behavioral measurements on the same cohort of mice. In view of the possible cross-talk interactions between brain parameters and cognitive performance, we presently investigated the extent to which the phenotypic expression of APOE ε4 and APOE ε4 in targeted replacement mice is affected by behavioral testing. This was performed using young, naïve APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice in which the levels of distinct brain parameters are affected by the APOE genotype (e.g., elevated levels of amyloid beta [Aβ] and hyperphosphorylated tau and reduced levels of vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT) in hippocampal neurons of APOE ε4 mice). These mice were exposed to a fear-conditioning paradigm, and the resulting effects on the brain parameters were examined. The results obtained revealed that the levels of Aβ, hyperphosphorylated tau, VGluT, and doublecortin of the APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice were markedly affected following the exposure of APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice to the fear-conditioning paradigm such that the isoform-specific effects of APOE ε4 on these parameters were greatly diminished.

The finding that behavioral testing affects the APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 phenotypes and masks the differences between them has important theoretical and practical implications and suggests that the assessment of brain and behavioral parameters should be performed using different cohorts.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE ε4), Behavior, Fear conditioning, Learning, Synapses, Targeted replacement mice

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most prevalent form of dementia in the elderly, is characterized by the occurrence of brain senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles and by the loss of brain synapses and neurons, which are associated with cognitive decline [1], [2], [3]. Genetic studies revealed the allelic segregation of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene to families with a higher risk of late-onset AD and of sporadic AD [4], [5], [6]. There are three major alleles of APOE, termed ε4 (APOE ε4), which are risk factors for AD, ε3 (APOE ε3), and ε2 (APOE ε2). The frequency of the apoE4 allele in healthy humans is ∼25%, whereas in sporadic AD it is greater than 50%, and APOE ε4 increases the risk for AD by lowering the age of onset of the disease by 7 to 9 years per allele copy [5]. Pathologically, APOE ε4 is associated with elevated intracellular levels of amyloid beta (Aβ) [7], [8], hyperphosphorylation of tau at specific loci [9], [10], and synaptic pathology and impaired neuronal plasticity [11], [12]. Declining memory and brain pathology have been reported in middle-aged APOE ε4 carriers with an ongoing normal clinical status [13], [14], suggesting that the pathological effects of apoE4 begin decades before the onset of AD.

APOE ε4-and apoE-targeted replacement mice are used extensively as a model for investigating the pathological effects of APOE ε4. Accordingly, behavioral experiments revealed that young apoE4 mice display impairments in object recognition [15], [16], [17], and in contextual fear conditioning [16], [18], [19], and in their performance in the Morris water maze [16], [20], [21], [22]. Furthermore, these behavioral impairments were associated with the accumulation of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau and with reduced levels of the presynaptic glutamatergic marker VGluT in hippocampal neurons of naïve APOE ε4 mice [20], [23]. Behavioral studies showing no genotype differences or enhanced performance of APOE ε4 mice have also been reported [24], [25], suggesting that the cognitive performance of the APOE ε4 mice can be affected by several additional parameters such as stress and experimental design.

Previous findings have shown that the exposure of APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice to environmental enrichment (EE) has differential effects on APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice [26], [27]. Accordingly, EE triggers synaptogenesis and neurogenesis in the APOE ε3 mice, whereas in the corresponding apoE4 mice it triggers apoptosis [27]. This provides a proof of principle that the APOE phenotype and the differences between the APOE ε4 and APOE ε4 mice can be modulated by behavioral manipulation. In the present study we wanted to examine whether shorter learning and memory-related behavioral treatments, to which the APOE mice are often subjected, can affect the phenotypic expression of APOE. Accordingly, young naïve APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice were exposed to a fear-conditioning paradigm or to the corresponding sham treatment, whereas a different cohort of mice was subjected to the novel object recognition paradigm. The extent to which this affected the accumulation of the AD hallmarks, Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau, and the levels of VGluT and doublecortin (DCX) in hippocampal neurons was determined. It is instrumental to determine whether behavioral testing can affect brain and subsequent physiological parameters factors, as if so, behavioral and biochemical experiments should be performed on different cohorts of mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

APOE-targeted replacement mice, in which the endogenous mouse APOE was replaced by either human APOE ε3 or APOE ε4, were created by gene targeting [28], and were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice were back-crossed to wild-type C57BL/6J mice (Harlan 2BL/610) for 10 generations and were homozygous for the APOE ε3 (3/3) or APOE ε4 (4/4) alleles. These mice are referred to in the text as APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice, respectively. The APOE genotype of the mice was confirmed by PCR analysis, as described previously [26], [29]. It should be noted that the Harlan C57BL/6J mice lack Synuclein. All the experiments were performed on a 4-month-old male mice, and were approved by the Tel-Aviv University Animal Care Committee.

2.2. Fear-conditioning test

This test, which assesses emotion-associated and contextual learning [18], [30], [31], was performed as described in ref. [16]. Accordingly, on day 1, the mice were placed in a conditioning chamber (context A with light and a metal grid floor) for 300 seconds during which, they were subjected to a 2.9 kHz tone, applied for 30 seconds at 80 dB (conditioned stimuli or CS) followed by a single electrical shock of 1 mA (unconditioned stimuli or US). On day 2, the mice were placed in a different chamber (context B, which had no contextual cues) and were subjected to two 20-second tones separated by a 40-second interval. On day 3 the mice were placed in the original conditioning chamber (context A) and kept there for 300 seconds without being subjected to either the tone or the foot shock. The mice were euthanized on day 5. The freezing behavior of the mice, which is an indication of fear memory, was recorded and analyzed using the FreezFrame 3.0 video tracking software system and the FreezView software system [19], [30], [32], [33]. Sham-treated mice were subjected to the same chambers and duration as the fear-conditioned mice but were not subjected to any tone or shock.

2.3. Object recognition test

This test, which is based on the natural tendency of rodents to investigate a novel object, was performed as previously described [16]. Accordingly, on day 1, the mice were first placed in an arena (60 × 60 cm, with 50-cm walls) in the absence of objects for 10 minutes. On day 2, the mice were subjected to two identical objects (A + A) for 5 minutes Two hours later, the mice's short-term memory was examined using one old and one novel object (A + B) for 5 minutes. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were reintroduced to the arena for 5 minutes with a novel object (B + C) to examine their long-term memory. The time spent near each object was measured and the results are presented as the ratio (novel)/(novel + familiar), where values higher than 0.5 are indicative of a preference for the new object, which indicates that the mouse remembers and differentiates between the new and the old object. The mice were euthanized 48 hours after being tested in the object recognition test.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and perfused transcardially with phosphate buffer saline. Their brains were then removed and halved, and each hemisphere was further processed for either histological or biochemical analysis, as previously described [20]. In brief, one brain hemisphere was fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and then placed in 30% sucrose for 48 h. Frozen coronal sections (30 μm) were then cut on a sliding microtome, collected serially, placed in 200 μl of cryoprotectant (containing glycerin, ethylene glycol, and 0.1 M sodium-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), and stored at −20°C until use. Free-floating sections were immunostained with the following primary antibodies (Abs): rabbit anti-Aβ42 (1:500; Chemicon, Temecula, CA); rabbit anti-202/205 phosphorylated tau (AT8, 1:200, Innogenetics); guinea-pig anti-VGluT1 (1:2000; Millipore); and goat anti-DCX (1:200; Santa Cruz). The immunostained sections were viewed using a Zeiss light microscope (Axioskop, Oberkochen, Germany) interfaced with a CCD video camera (Kodak Megaplus, Rochester, NY, USA). Pictures of stained brains were obtained at ×10 magnification. VGluT staining was performed using immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence was visualized using a confocal scanning laser microscope (Zeiss, LSM 510). Images (×20 magnification 1024 × 1024 pixels, 12 bit) were acquired by averaging eight scans. Analysis and quantification of the staining in Cornu Ammonis region 3 (CA3) (in which the effects of the apoE genotype were previously shown to be most pronounced [20]), and in the dentate gyrus (DG) for DCX (neurogenesis in the hippocampus is located in the DG) were performed using the Image-Pro plus system for image analysis (v. 5.1, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The intensities of digital audio broadcasting (DAB) staining or immunofluorescence staining were expressed as the percentage of the area stained, as previously described [34]. All images for each immunostaining were obtained under identical conditions, and their quantitative analyses were performed with no further handling. Moderate adjustments for contrast and brightness were performed evenly on all the presented images of the different mouse groups.

2.5. Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described [35], [36]. In brief, one brain hemisphere was taken; the hippocampus was removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C until use. The dissected hippocampus samples from each brain were then homogenized in 200 μl of the following detergent-free homogenization buffer (10 mM HEPES, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 2 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma P8340] and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [Sigma P5726]). The homogenates were then liquidated and stored at −70°C. Gel electrophoresis and immunoblot assays were performed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-treated samples (boiling for 10 min in 0.5% SDS) as previously described [34], [35] using the following antibodies: goat anti-APOE (1:10,000, Chemicon) and rabbit anti-ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 (ABCA1, 1:500; Novous). Protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce 23225). The immunoblot bands were visualized using the ECL substrate (Pierce), after which their intensity was quantified using EZQuantGel software (EZQuant, Tel-Aviv, Israel). GAPDH levels were used as gel loading controls and the results are presented relative to the apoE3 mice.

3. Results

3.1. Fear-conditioning test

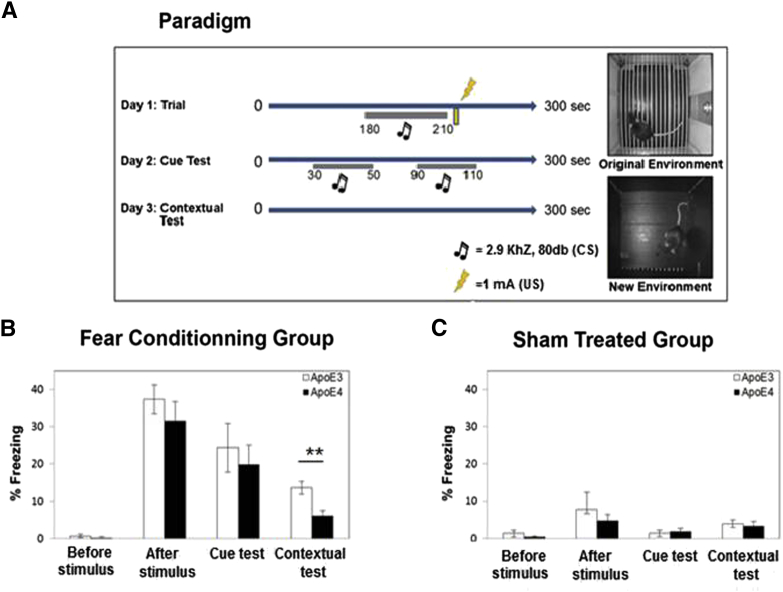

APOE ε4-and APOE ε3-targeted replacement mice were subjected to a fear-conditioning test in which their freezing response to a tone (CS) coupled with electrical stimulation (US) was assessed. Twenty-four hours following stimulation, the mice were assessed by a cue test in which their freezing in novel cages following exposure to the tone was determined. This was followed by context testing after 48 hours in which the percentage of the mice that were freezing was determined following their reintroduction to the cages where the shock was administered. The APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice displayed negligible freezing before stimulation. However, both mouse groups froze significantly and equally after exposure to the combined electrical and tone stimuli (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fear conditioning test. Apolipoprotein (APOE ε3) and APOE ε4 mice were subjected to a coupled fear conditioning test (tone as the conditional stimulus, followed by electrical stimulation as the unconditional stimulus), or sham treated as described in section 2. (A) The paradigm. On day 1 the mice received the electrical and tone stimulation, on day 2 they were exposed to the sound in a different chamber, whereas on day 3 they were exposed to the original conditioning chamber without any stimulation. (B) The fear conditioning test. The results presented (mean ± SEM; n = 8–10 per group) correspond to the percentage of freezing time after stimulation on day 1, following the cue on day 2, and with the contextual test on day 3. They were obtained using the EthoVision computerized system and the FreezeFrame programs described in section 2. ∗∗P < .01. (C) Sham treatment. The results presented (mean ± SEM; n = 8–10 per group) correspond to the percentage of freezing time of the sham-treated mice. Results shown are as in (B) except that the mice were not subjected to the electrical and tone stimulations.

A subsequent cue memory experiment revealed that the APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice froze similarly following exposure to tone in a new environment, whereas in the subsequent context test the APOE ε4 mice froze significantly less than did the APOE ε3 mice when they were returned to the original chamber with no further stimulation (Fig. 1). Control sham treatment, in which both mouse groups were similarly treated except that no stimulus was given, resulted in an insignificant freezing response during all stages of the paradigm (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results indicate that APOE ε4 impairs contextual memory but not cue-driven memory. The contextual memory is hippocampus dependent, whereas the cue test is related to the amygdala [18]. These results are thus in accordance with our previous findings that APOE ε4 induces distinct hippocampal impairment [16].

3.2. The effect of fear-conditioning testing on brain parameters

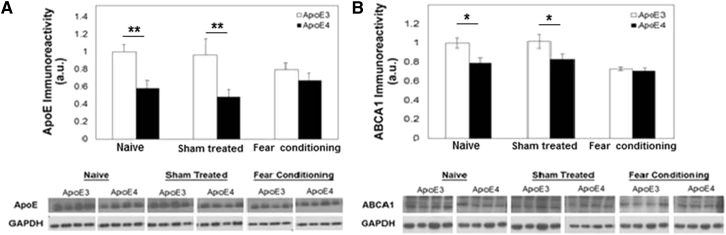

3.2.1. APOE and the lipidation protein ABCA1

Immunoblot measurements of the levels of these proteins in the hippocampi of APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice revealed, in accordance with previous publications [20], [23], lower levels in APOE ε4 than in the APOE ε3 mice (Fig. 2). Exposure of the mice to the fear-conditioning paradigm abolished the differences between the APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice for both parameters. In the case of APOE, this was associated with an elevated level of APOE ε4, rendering it equal to APOE ε3, whereas in the case of ABCA1, the fear-conditioning paradigm was associated with a specific reduction of its levels in the APOE ε3 mice (Fig. 2). Control sham experiments, in which both mouse groups were similarly treated except that no stimuli was given, had no effect on the levels of either apoE or ABCA1 (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Apolipoprotein (APOE) (A) and ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 (B) levels in the hippocampus of naïve, sham-treated, and fear conditioned APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice. Representative immunoblots are presented in the lower panels. Quantization of the results (mean ± SEM; n = 8–10 per group) and their levels relative to the levels of naïve apoE3 mice are shown in the upper panels.∗P < .05. ∗∗P < .01.

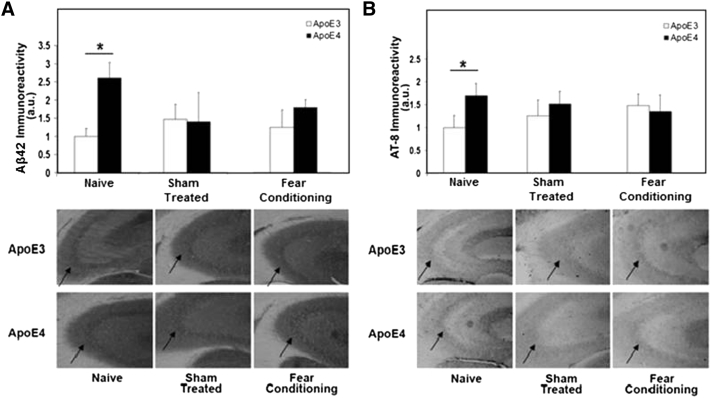

3.2.2. Accumulation of Aβ42 and hyperphosphorylated tau in hippocampal neurons

In accordance with previous histological and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) experiments [20], the levels of intraneuronal Aβ42 and hyperphosphorylated tau (e.g. Monoclonal antibody AT8) in CA3 neurons were higher in hippocampal neurons of APOE ε4 mice compared with the corresponding APOE ε3 mice (Fig. 3). Interestingly, both of these histological effects were abolished in sham control-treated mice that were exposed to the same handling and environmental changes as were the stimulated mice but without the electrical and tone stimulation, and the associated learning. In the case of Aβ42 the effect was associated with reduced Aβ42 levels in the APOE ε4 mice, rendering them similar to the apoE3 mice, which were not affected by this handling (Fig. 3A). However, regarding hyperphosphorylated tau (e.g. AT8), this was associated with reduced hyperphosphorylated tau in the APOE ε4 mice and a small elevation of hyperphosphorylated tau in the APOE ε3 mice. Importantly, these parameters were not further affected by exposing the mice to the electrical and tone stimuli, and the concurrent learning process (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Amyloid beta (Aβ42) (A) and hyperphosphorylated tau (monoclonal antibody [mAb] AT-8) (B) levels in CA3 neurons of naïve, sham-treated, and fear-conditioned APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice. Aβ42 and AT-8 immunohistochemistry was performed as described in section 2. Sections stained with either anti-Aβ42 or mAb AT-8 are presented in the lower panels. Quantization of the results (mean ± SEM; n = 8–10 per group) and their levels relative to the levels of naïve APOE ε3 mice are shown in the upper panels. ∗P < .05.

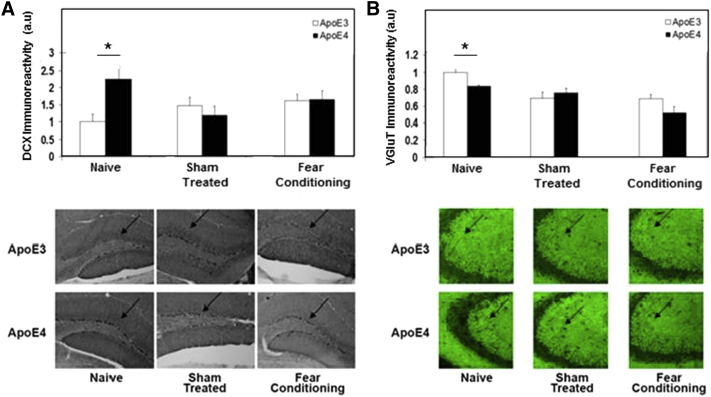

3.2.3. Neuronal pathology

We next examined the extent to which exposure to the fear-conditioning paradigm affects APOE ε4-driven neuronal pathology. This was first assessed by using DCX, which is a specific marker of newly formed neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus [37]. The levels of DCX-positive neurons in the dentate gyrus were found to be higher in naïve APOE ε4 than in the corresponding apoE3 mice (Fig. 4A), which is in accordance with previous observations obtained with APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 transgenic mice [27]. This effect was abolished, however, by subjecting the mice to sham control treatment and was not further affected by the electrical and tone stimulations (Fig. 4A). We next measured the effects of the APOE genotype and behavioral testing on the levels of the presynaptic glutamate transporter (VGluT). This revealed that, in accordance with previous observations [20], [23], the levels of VGluT in CA3 neurons were lower in the APOE ε4 than in the APOE ε3 mice (Fig. 4B). However, as observed with DCX, this effect was abolished following exposure of the mice to control sham treatment and was not further affected by the electrical and tone stimuli (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Doublecortin (DCX) (A) and VGluT (B) levels in hippocampal neurons of naïve, sham-treated, and fear-conditioned apoE3 and apoE4 mice. The levels of DCX in the dentate gyrus and of VGluT in CA3 neurons were determined immunohistochemically, as described in section 2. Representative sections stained with either anti-DCX or anti-VGluT are presented in the lower panels. Quantization of the results (mean ± SEM; n = 8–10 per group) and their levels relative to the levels of naïve apoE3 mice are shown in the upper panels. ∗P < .05.

Taken together, these results indicate that exposure to behavioral testing, using the fear conditioning paradigm, results in a marked effect on the phenotypic expression of the APOE ε4 genotypes. For some parameters, such as APOE and ABCA1, this is induced by the electrical and tone stimulations, whereas other APOE ε4-driven phenotypes (e.g., Aβ, tau hyperphosphorylation, and the neuronal parameters DCX and VGluT) are already affected by sham treatments of the mice.

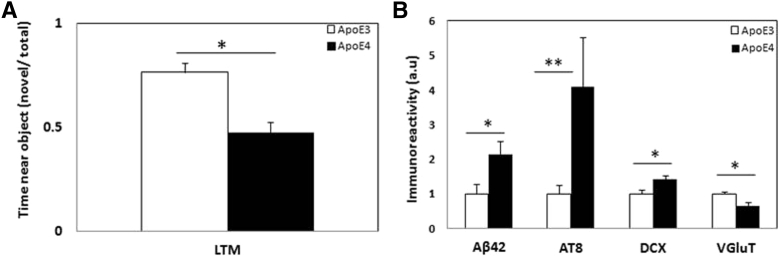

3.2.4. Novel object recognition test

These experiments examined the extent to which subjecting the mice to the novel object recognition test affects the brain phenotypic expression of APOE ε3 and APOE ε4. As shown in Fig. 5A and in accordance with our previous findings [16], the APOE ε3 mice but not the APOE ε4 mice choose preferentially the novel object. Importantly, and unlike in the fear-conditioning test, the brain parameters of the object recognition-tested APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice were not affected by the test and were similar to those of the naïve mice (compare Fig. 5B to Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 and APOE ε3 object recognition test and its effect on brain parameters. Naïve APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice were subjected to the object recognition test after which the levels of the indicated brain parameters were determined as outlined in section 2. (A) The ratio between the time spent by the APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice near the novel object to the total time spent near both the familiar and novel objects. (B) Immunohistochemical comparison of the levels of amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42), phosphorylated tau (AT8), and VgluT in CA3 and doublecortin in the dentate gyrus hippocampal neurons. Results shown represent the mean ± SEM of n = 8–10 mice per group. ∗P < .05 for a comparison of the APOE ε4 and the APOE ε3 groups.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the extent to which the exposure of APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice to behavioral paradigms affects their brain parameters and whether it modulates the APOE genotype-dependent differences between these mice. This was pursued by exposing young APOE ε4-and APOE ε4-targeted replacement mice to the fear-conditioning and object recognition paradigms and examining the resulting effects on distinct hippocampal parameters, including the neuronal levels of the AD hallmarks, Aβ42, and hyperphosphorylated tau, the synaptic and neuronal parameters, VGluT and DCX, and APOE and its lipidation protein, ABCA1. This revealed that the APOE ε4 mice had impaired contextual memory and that all the physiological parameters were affected by the fear-conditioning treatment such that the phenotypic differences between APOE ε3 and APOE ε4, which were apparent in these mice under naïve conditions, were virtually abolished following these treatments. Two types of effects were thus observed. The first type, which included Aβ42 and AT-8, and DCX and VGluT, was already caused by the sham treatment, namely, exposure to the chambers of the fear conditioning paradigm without administering the shock and the tone, and these treatments were not further affected by the electrical and tone stimulation or by the concurrent learning process. The finding that the fear-conditioning experiment has no additional effect on these parameters may be due to a ceiling effect or because these parameters are not affected by the electrical and tone stimulation. The second group of parameters included APOE and ABCA1, whose levels were affected only following the electrical and tone stimulation. In contrast, the object recognition paradigm had no effect on the corresponding brain parameters of the APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice. Preliminary experiments, using the Morris Water Maze test, revealed that this test, which is also associated with stress, also affects the brain parameters and abolishes the differences between the APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice. These results are in accordance with and extend previous findings that showed that the exposure of wild-type mice to fear conditioning induces distinct brain effects such as endurable epigenetic changes [38] and an increase in the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [39] and differential methylation in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) promoter [40]. The finding that the APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice respond differently to fear-conditioning testing and that this exposure virtually abolishes the phenotypic difference between the APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 mice is of great experimental importance and shows that the analysis of biochemical markers and behavioral measurements in the same cohort can mask biochemical differences that are apparent under naïve conditions.

The behavioral experience of the sham-treated mice involves both handling and exposure to a new environment. Previous studies showed that the exposure of young naïve wild-type mice to an enriched environment induces brain biochemical changes [4] and that handling of the mice induces physiological and biochemical changes in various systems including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [41], long-term potentiating [42], and behavioral effects [43], and various other phenotypes [44]. The extent to which the presently observed effects of the sham treatment on hippocampal Aβ42, AT-8, VGluT, and DCX levels are related to handling and/or to exposure to a specific environment are not known. Importantly, the novel object recognition test, which also includes handling and exposure to a new environment, induced no differences in the phenotypic expression of the APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice. The mechanisms which specifically mediate the effects of the fear conditioning sham treatment but which are not involved in the novel recognition test remain to be determined. The second group of parameters, which includes APOE and the APOE lipidation protein, ABCA1, were affected only by the actual fear condition treatment and not by the sham treatment. These paradigms involve stress and learning experiences and it is thus possible that the observed changes in the hippocampal levels of APOE and ABCA1 are related to stress and/or to learning.

Recent findings suggest that human APOE ε4 carriers are particularly susceptible to stress [45], [46], [47]. Accordingly, the brain parameters whose levels are affected by the electrical stimulation, which is clearly stress-related, probably model a similar stress-related effect in the mouse. However, it remains to be determined whether the brain parameters that were affected by milder treatments, such as the sham treatment of the fear conditioning experiment, are associated with a more subtle stress response which is not apparent in the object recognition test and whether such effects can also be observed in aged AD patients.

In conclusion, the results thus obtained indicate that the exposure of APOE ε4- and APOE ε4-targeted replacement mice to behavioral testing has marked effects on hippocampal, neuronal, and biochemical parameters and that it masks the phenotypic differences between these mice, which are apparent under naïve conditions. This has important theoretical and practical implications and suggests that the assessment of brain and behavioral parameters should be performed on different cohorts of mice.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 is the most prevalent genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD). Experiments with APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mouse models involve the pursuit of biochemical and behavioral measurements that often use the same cohort of mice. A growing body of evidence suggests that environmental and behavioral manipulations can greatly affect brain parameters and physiology. We presently investigated, using targeted replacement mice that express APOE ε4 or APOE ε3, the extent to which exposure to fear conditioning and object recognition paradigms can affect key biochemical phenotypes of APOE ε3 and APOE ε4.

-

2.

Interpretation: The results obtained revealed that fear conditioning and even sham behavioral treatment has marked effects on the brains of the APOE ε4 mice and abolishes the phenotypic differences between the APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 mice. In contrast, the object recognition test, in which the behavioral manipulation is milder, did not affect the APOE ε4 and APOE ε3 brain phenotypes. These results show that the brains of APOE ε4 mice are particularly susceptible to changes in the environmental conditions that are associated with cognitive testing.

-

3.

Future directions: These results point to the need to include in mouse biochemical and behavioral studies some measurements of the effects of behavioral manipulation on the mouse brain. Additionally, the results show that at least for young mice, behavioral testing can counteract the APOE ε4 phenotype. The extent to which the pathological effect of apoE4 in aged mice, or even in AD, can be counteracted by similar behavioral treatments is not known and constitutes a promising hypothesis to be investigated in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alex Nakaryakov in Smolar for technical assistance and for maintaining the mouse colonies. This research was supported (in part) by “The legacy heritage bio medical program of the israel science foundation” (grant No. 1575/14), from the Joseph K. and Inez Eichenbaum Foundation, and the Harold and Eleanore Foonberg Foundation. DMM is the incumbent of the Myriam Lebach Chair in Molecular Neurodegeneration.

References

- 1.Alzheimer A., Stelzmann R.A., Schnitzlein H.N., Murtagh F.R. An english translation of Alzheimer's 1907 paper, “Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde”. Clin Anat. 1995;8:429–431. doi: 10.1002/ca.980080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tesseur I., Zou K., Esposito L., Bard F., Berber E., Can J.V. Deficiency in neuronal TGF-beta signaling promotes neurodegeneration and Alzheimer's pathology. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3060–3069. doi: 10.1172/JCI27341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masters C.L., Simms G., Weinman N.A., Multhaup G., McDonald B.L., Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corder E.H., Saunders A.M., Strittmatter W.J., Schmechel D.E., Gaskell P.C., Small G.W. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roses A.D. Apolipoprotein E alleles as risk factors in Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:387–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saunders A.M., Strittmatter W.J., Schmechel D., George-Hyslop P.H., Pericak-Vance M.A., Joo S.H. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1467–1472. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori E., Lee K., Yasuda M., Hashimoto M., Kazui H., Hirono N. Accelerated hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer's disease with apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:209–214. doi: 10.1002/ana.10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmechel D.E., Saunders A.M., Strittmatter W.J., Crain B.J., Hulette C.M., Joo S.H. Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9649–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strittmatter W.J., Saunders A.M., Goedert M., Weisgraber K.H., Dong L.M., Jakes R. Isoform-specific interactions of apolipoprotein E with microtubule-associated protein tau: implications for Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11183–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunderland T., Mirza N., Putnam K.T., Linker G., Bhupali D., Durham R. Cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid1-42 and tau in control subjects at risk for Alzheimer's disease: the effect of APOE epsilon4 allele. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arendt T., Schindler C., Bruckner M.K., Eschrich K., Bigl V., Zedlick D. Plastic neuronal remodeling is impaired in patients with Alzheimer's disease carrying apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele. J Neurosci. 1997;17:516–529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egensperger R., Kosel S., von Eitzen U., Graeber M.B. Microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: association with APOE genotype. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiman E.M., Chen K., Liu X., Bandy D., Yu M., Lee W. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6820–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heise V., Filippini N., Ebmeier K.P., Mackay C.E. The APOE varepsilon4 allele modulates brain white matter integrity in healthy adults. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;16:908–916. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benice T.S., Raber J. Object recognition analysis in mice using nose-point digital video tracking. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;168:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salomon-Zimri S., Boehm-Cagan A., Liraz O., Michaelson D.M. Hippocampus-related cognitive impairments in young apoE4 targeted replacement mice. Neurodegener Dis. 2014;13:86–92. doi: 10.1159/000354777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichol K., Deeny S.P., Seif J., Camaclang K., Cotman C.W. Exercise improves cognition and hippocampal plasticity in APOE epsilon4 mice. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segev Y., Michaelson D.M., Rosenblum K. ApoE epsilon4 is associated with eIF2alpha phosphorylation and impaired learning in young mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:863–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsen R.H., Agam M., Davis M.J., Raber J. ApoE isoform-dependent deficits in extinction of contextual fear conditioning. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11:806–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liraz O., Boehm-Cagan A., Michaelson D.M. ApoE4 induces Abeta42, tau, and neuronal pathology in the hippocampus of young targeted replacement apoE4 mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raber J., Wong D., Buttini M., Orth M., Bellosta S., Pitas R.E. Isoform-specific effects of human apolipoprotein E on brain function revealed in ApoE knockout mice: increased susceptibility of females. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10914–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veinbergs I., Mallory M., Mante M., Rockenstein E., Gilbert J.R., Masliah E. Differential neurotrophic effects of apolipoprotein E in aged transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 1999;265:218–222. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehm-Cagan A., Michaelson D.M. Reversal of apoE4-driven brain pathology and behavioral deficits by bexarotene. J Neurosci. 2014;34:7293–7301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5198-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau P.H., Bott J.B., Zerbinatti C., Renger J.J., Kelche C., Cassel J.C. ApoE4 confers better spatial memory than apoE3 in young adult hAPP-Yac/apoE-TR mice. Behav Brain Res. 2013;243:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegel J.A., Haley G.E., Raber J. Apolipoprotein E isoform-dependent effects on anxiety and cognition in female TR mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levi O., Jongen-Relo A.L., Feldon J., Roses A.D., Michaelson D.M. ApoE4 impairs hippocampal plasticity isoform-specifically and blocks the environmental stimulation of synaptogenesis and memory. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;13:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levi O., Michaelson D.M. Environmental enrichment stimulates neurogenesis in apolipoprotein E3 and neuronal apoptosis in apolipoprotein E4 transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2007;100:202–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan P.M., Mezdour H., Aratani Y., Knouff C., Najib J., Reddick R.L. Targeted replacement of the mouse apolipoprotein E gene with the common human APOE3 allele enhances diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17972–17980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belinson H., Michaelson D.M. ApoE4-dependent Abeta-mediated neurodegeneration is associated with inflammatory activation in the hippocampus but not the septum. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:1427–1434. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips R.G., LeDoux J.E. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryan KJ, Lee H, Perry G, Smith MA, Casadesus G. Transgenic mouse models of alzheimer's disease: behavioral testing and considerations. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 32.Kornecook TJ, McKinney AP, Ferguson MT, Dodart JC. Isoform-specific effects of apolipoprotein E on cognitive performance in targeted-replacement mice overexpressing human APP. Genes Brain Behav 2009;9:182–192. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Fitz Nicholas F. AAC, Iliya Lefterov, Radosveta Koldamova. RXR agonist bexarotene restores memory deficits but does not affect Aβ plaques in APP/PS1 mice expressing human APO isoforms. AD/PD. Florence, Italy 2013.

- 34.Belinson H., Lev D., Masliah E., Michaelson D.M. Activation of the amyloid cascade in apolipoprotein E4 transgenic mice induces lysosomal activation and neurodegeneration resulting in marked cognitive deficits. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4690–4701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haas A., Liraz O., Michaelson D.M. The effects of apolipoproteins E3 and E4 on the transforming growth factor-beta system in targeted replacement mice. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10:41–45. doi: 10.1159/000334902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kariv-Inbal Z., Yacobson S., Berkecz R., Peter M., Janaky T., Lutjohann D. The isoform-specific pathological effects of apoE4 in vivo are prevented by a fish oil (DHA) diet and are modified by cholesterol. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28:667–683. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Encinas J.M., Sierra A., Valcarcel-Martin R., Martin-Suarez S. A developmental perspective on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2013;31:640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravi B., Kannan M. Epigenetics in the nervous system: an overview of its essential role. Indian J Hum Genet. 2013;19:384–391. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.124357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schafe G.E., Atkins C.M., Swank M.W., Bauer E.P., Sweatt J.D., LeDoux J.E. Activation of ERK/MAP kinase in the amygdala is required for memory consolidation of pavlovian fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8177–8187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08177.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lubin F.D. Epigenetic gene regulation in the adult mammalian brain: multiple roles in memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine S. Infantile experience and resistance to physiological stress. Science. 1957;126:405. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3270.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson D.A., Willner J., Kurz E.M., Nadel L. Early handling increases hippocampal long-term potentiation in young rats. Behav Brain Res. 1986;21:223–227. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(86)90240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cannizzaro C., Martire M., Steardo L., Cannizzaro E., Gagliano M., Mineo A. Prenatal exposure to diazepam and alprazolam, but not to zolpidem, affects behavioural stress reactivity in handling-naive and handling-habituated adult male rat progeny. Brain Res. 2002;953:170–180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cirulli F., Berry A., Bonsignore L.T., Capone F., D'Andrea I., Aloe L. Early life influences on emotional reactivity: evidence that social enrichment has greater effects than handling on anxiety-like behaviors, neuroendocrine responses to stress and central BDNF levels. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:808–820. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peavy G.M. The effects of stress and APOE genotype on cognition in older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1376–1378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee B.K., Glass T.A., Wand G.S., McAtee M.J., Bandeen-Roche K., Bolla K.I. Apolipoprotein e genotype, cortisol, and cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1456–1464. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheffler J., Moxley J., Sachs-Ericsson N. Stress, race, and APOE: understanding the interplay of risk factors for changes in cognitive functioning. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:784–791. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.880403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]