Abstract

Alcohol use and impulsivity are two known risk factors for intimate partner violence (IPV). The current study examined the independent and interactive effects of problematic drinking and five facets of impulsivity (i.e., negative urgency, positive urgency, sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance) on perpetration of physical IPV within a dyadic framework. Participants were 289 heavy drinking heterosexual couples (total N = 578) with a recent history of psychological and/or physical IPV recruited from two metropolitan U.S. cities. Parallel multilevel Actor Partner Interdependence Models were utilized and demonstrated Actor problematic drinking, negative urgency, and lack of perseverance were associated with physical IPV. Findings also revealed associations between Partner problematic drinking and physical IPV as well as significant Partner Problematic Drinking x Actor Impulsivity (Negative Urgency and Positive Urgency) interaction effects on physical IPV. Findings highlight the importance of examining IPV within a dyadic framework and are interpreted using the I3 meta-theoretical model.

Keywords: intimate partner aggression, self-control, heavy drinking, actor-partner interdependence model

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public health problem. An estimated 22% of women and 14% of men have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner during their lifetime (Black et al., 2011) and more than 50% of couples attending marital therapy report at least one episode of physical IPV in the past year (Jose & O’Leary, 2009). Although a host of individual and contextual risk factors for IPV have been identified (e.g., Capaldi, Shortt & Kim, 2005; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2002), disproportionately less research has examined the influence of factors across multiple ecological levels (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; O’Leary, Smith Slep, & O’Leary, 2007; Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004). The present study sought to address this need by examining two person-level predictors of IPV within a relational context: problematic drinking (for a review, see Foran & O’Leary, 2008) and impulsivity (e.g., Schafer, Caetano, & Cunradi, 2004; Stuart & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2005). Problematic drinking was defined as a pattern of alcohol use that increases the risk of or results in negative consequences for the drinker or others. Only two studies have examined the interactive effect of impulsivity and alcohol consumption on IPV (Schumacher, Coffey, Leonard, O’Jile, & Landy, 2013; Watkins, Maldonado, & DiLillo, 2014), and only one of these specifically examined how these risk factors interact within a relational context (Watkins et al., 2014). This is not surprising given that research has only recently begun to account for the dyadic context of IPV through the use of advanced statistical techniques including Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (APIM; Kenny & Cook, 1999; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Such analytic approaches allow researchers to account for both actor effects (e.g., how much one’s current behavior is predicted by his/her own behavior) and partner effects (e.g., how much one’s behavior is influenced by his/her partner’s behavior). To this end, the purpose of the present study was to examine the independent and interactive effects of problematic drinking and impulsivity on physical IPV perpetration within a dyadic framework.

Impulsivity and IPV

Research indicates a robust association between impulsivity, or the inability to regulate certain behaviors, and various forms of aggressive behavior (e.g., Abbey et al., 2002; Hynan & Grush, 1986; Netter et al., 1998), including IPV (e.g., Cohen et al., 2003; Shorey, Brasfield, Febres, & Stuart, 2010; Schafer et al., 2004). Cross-sectional research indicates that men who report IPV perpetration are higher in impulsivity compared to men who do not report IPV (Cohen et al., 2003). Similarly, impulsivity is related to both psychological (Shorey et al., 2010) and physical (Cunradi, Todd, Duke, & Ames, 2009; Schafer et al., 2004) IPV perpetration among women. Taking into account the dyadic relationship of IPV, research suggests both partners’ impulsivity is associated with unidirectional and bidirectional IPV (Cunradi, Ames, & Duke, 2011; Cunradi et al., 2009).

The reviewed literature has conceptualized impulsivity as a unidimensional construct, despite research and theory suggesting impulsivity is comprised of a cluster of lower-order traits (Dick et al., 2010). Although various models of impulsivity have been advanced (e.g., Eysenck & Eysenck, 1968; Zuckerman, 1994), none have garnered widespread acceptance. To this end, Whiteside and Lynam (2001) identified four distinct facets of personality that reflect different pathways to impulsive behavior: lack of premeditation, negative urgency, sensation seeking, and lack of perseverance. Lack of premeditation refers to an individual’s tendency to reflect on outcomes of an action before partaking in the act. Individuals high in lack of premeditation act without thinking about future consequences, whereas those low in lack of premeditation are considered thoughtful and deliberate. Negative urgency refers to one’s tendency to act rashly in response to negative affect. Those high in negative urgency act impulsively to relieve negative affect “in the moment”, despite the likelihood that their actions will result in negative long-term consequences. Sensation seeking refers to an inclination to pursue activities that are arousing and a willingness to try new, dangerous things. Finally, lack of perseverance refers to an individual’s tendency to lose focus and lack persistence through a boring task. Those high in lack of perseverance struggle to complete unpleasant tasks. Cyders and colleagues (2007) extended this four-facet model to include one’s tendency to behave impulsively when experiencing positive affect (i.e., positive urgency).

Two studies that have adopted this conceptualization suggest there may be a nuanced relationship between these distinct facets of impulsivity and perpetration of IPV. Miller and colleagues (2003) applied the four-factor model of impulsivity to IPV and demonstrated that all four facets were related to self-reported intimate partner aggression measured by the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus & Gelles, 1990); however, only negative urgency accounted for significant variance in aggression when all four facets were accounted for simultaneously. It was concluded that because the CTS likely captures reactive aggression toward one’s partner under hostile or angry conditions, the unique association between IPV perpetration and negative urgency is likely due to the overlapping presence of negative affect across constructs. Derefinko and colleagues (2011) applied the revised five-facet model of impulsivity (Cyders et al., 2007) and found that positive and negative urgency were both associated with IPV in a sample of college men. Consistent with this work, studies outside the IPV literature also suggest that negative urgency is positively associated with self-reported aggression toward others (Settles et al., 2012) and displaced aggression toward a stranger in a laboratory setting (Scott, DiLillo, Maldonado, & Watkins, 2015). Collectively, this preliminary evidence suggests that negative urgency, and potentially positive urgency, are most associated with IPV and aggression generally. However, no study has accounted for impulsivity of both partners. Thus, it remains unclear how these distinct facets of impulsivity function within a dyadic context.

Alcohol Use and IPV

It is clear that alcohol facilitates aggression (Bushman & Cooper, 1990) and equally clear that alcohol consumption is a leading contributing cause of aggression within intimate relationships (Leonard, 2005). Indeed, both men and women’s alcohol use predicts IPV perpetration in married and cohabiting couples (Testa et al., 2012; Testa, Quigley, & Leonard, 2003) and of all hazardous substance use patterns, alcohol use disorders are most strongly associated with IPV perpetration (Smith, Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius, 2012). Although cross-sectional studies demonstrate a small to moderate effect of alcohol use/abuse on male-to-female IPV and a small effect of alcohol use/abuse on female-to-male IPV (for review, see Foran & O’Leary, 2008), these effect sizes mask alcohol’s true effect on IPV by not taking into account key moderating factors. For instance, research indicates that alcohol consumption is more likely to facilitate IPV for individuals who evidence alcohol-aggression expectancies (Barnwell et al., 2006), dispositional aggression (Barnwell et al., 2006), an aggressive personality style (Heyman et al., 1995), a history of problem drinking (Heyman et al., 1995), avoidance coping and hostility (Schumacher et al., 2008), jealousy (Foran & O’Leary, 2008), and an external locus of control (Gallagher & Parrott, 2010). These Alcohol x Person interaction effects have been explained from varying perspectives, all of which share the common tenet that the pharmacological effect of alcohol decreases behavioral inhibition by increasing arousal (Giancola & Zeichner, 1997; Graham, Wells, & West, 1997) and disrupting higher order cognitive functioning (Giancola, 2004; Steele & Josephs, 1990). As a result, when sober, the proclivity for aggression incurred from a given risk factor may be masked via one’s capacity to inhibit socially inappropriate behavior; however, when intoxicated, one’s capacity to inhibit inappropriate behavior will be compromised and thereby increase the likelihood of aggression.

Within the extensive literature that examines individual-level moderators of alcohol-related IPV, very few studies take into account the characteristics of both partners. In fact, research on alcohol-related IPV has just recently begun to consider the effects of both partners’ alcohol use on IPV. For instance, research indicates that both partners’ alcohol use independently predicts the frequency of each partner’s physical IPV perpetration, and alcohol use by both partners interacts to predict men’s IPV perpetration (Testa et al., 2012). Additionally, research suggests actor heavy episodic drinking predicts partner-specific anger (Crane, Testa, Derrick, & Leonard, 2014), and actor and partner alcohol use predict physical and psychological IPV (Testa & Derrick, 2014; Woodin, Caldeira, Sotskova, Galaugher, & Lu, 2014). This work suggests potential influences of both the actor’s and their partner’s problematic drinking on IPV perpetration and highlights the importance of examining alcohol-related IPV within a dyadic framework. Indeed, by accounting for actor-partner effects, the true effect of problematic drinking on IPV perpetration may be better isolated.

Theoretical Framework

Several theoretical models of IPV perpetration highlight specific constructs or predictive factors associated with IPV; however the current investigation utilizes a parsimonious and inclusive framework that not only outlines variables that may be related to IPV, but also the fundamental processes (and their interaction) that are necessary and sufficient for IPV to occur (Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). The I3 meta-theoretical model for IPV seeks to explain whether, how, and for whom specific risk and protective factors for IPV exacerbate or mitigate aggression likelihood (Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). This model of IPV perpetration posits that the likelihood of partner conflict is best conceptualized in terms of process factors, or the combination of instigating triggers, impelling influences, and disinhibiting factors for given individuals in specific contexts (Finkel, 2007; Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). Instigating influences are those factors which normatively produce an urge to behave aggressively (e.g., provocation, relationship conflict). Impelling influences are those factors that alone may not cause aggression, but when an individual is faced with a relevant instigating influence, the impeller increases the likelihood of an aggressive urge (e.g., negative affect, anger). Inhibiting influences are those which increase the likelihood that someone will successfully resist an urge toward aggression (e.g., self-regulatory capacity). Factors such as alcohol use and limited emotion regulation skills may act as disinhibiting influences by sapping the integrity of a person’s inhibiting faculties (e.g., Denson, Pederson, Friese, Hahm, & Roberts, 2011; Finkel, DeWall, Slotter, Oaten, & Foshee, 2009).

Researchers have suggested that the pathway from alcohol intoxication to aggressive behavior primarily involves factors specifically related to inhibition (Giancola et al., 2010). In particular, evidence suggests that alcohol use and impulsivity may serve as independent as well as interactive disinhibiting factors. Indeed, in a study of treatment-seeking men, IPV was most likely to occur among men who consumed alcohol and reported high levels of impulsivity (Schumacher et al., 2013). However, as has been made clear, it is important to consider how the impulsivity and alcohol use of both partners influences IPV perpetration. To our knowledge, only one study has examined the effect of these variables on IPV perpetration within a dyadic framework. In their study of college couples, Watkins and colleagues (2014) found a significant Alcohol x Impulsivity interaction, such that actor hazardous alcohol use was positively associated with actor severity of IPV to a greater extent among actors with greater impulse control difficulties. Additionally, main effects of actor and partner impulse control difficulties, but not heavy drinking, were positively associated with actor perpetration of physical and psychological IPV. The authors concluded that the absence of a main effect of heavy drinking on IPV may be the result of study’s cross-sectional design; that is, their measures could not establish whether an individual consumed alcohol immediately prior to incidences of IPV. In addition, it is possible that main effects traditionally observed in this literature do not directly translate when alcohol-related IPV is examined within a dyadic framework. For this reason, additional research that examines the independent and interactive effects of problematic alcohol use and impulsivity (and other relevant risk factors) within a dyadic framework is sorely needed.

The Present Study

The present study seeks to extend these findings by (1) examining this relation in a sample of heavy drinking men and women with a history of relationship conflict (i.e., instigating influence), as conceptualized by recent psychological and/or physical IPV, and (2) examining the independent and interactive effects of facets of impulsivity and problematic drinking (i.e., disinhibiting influences) on perpetration of physical IPV within a dyadic framework. It was hypothesized that actor positive and negative urgency and actor problematic drinking would be positively related to greater actor physical IPV perpetration. Additionally, it was hypothesized actor alcohol problems would moderate the association between actor positive and negative urgency and physical IPV, such that the relation between impulsivity and physical IPV would be stronger among problematic drinkers compared to non-problematic drinkers. Finally, given that dearth of research to support a priori predictions of partner and actor-partner effects, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the independent and interactive effects of partner impulsivity and problematic drinking on physical IPV.

Method

The distinct set of hypotheses tested herein utilized data that were drawn from a larger investigation on the effects of acute alcohol intoxication and IPV. Although the focus of the present study did not examine effects of acute alcohol intoxication, couples were required to meet eligibility criteria for an alcohol administration study (see below). The present hypotheses are novel, and the analytic plan was developed specifically to address these aims.

Participants

Participants were 302 heterosexual couples (N = 604) recruited from two metropolitan U.S. cities through advertisements placed in online/social media sites, community newspapers, and public transportation. Couples were initially screened separately by telephone to assess eligibility, which was then verified in a more comprehensive in-person laboratory assessment. To be eligible, couples had to be dating for at least one month, be at least 21 years of age, and identify English as their native language. Couples were excluded if either partner reported serious head injuries, a condition in which alcohol is medically contraindicated, or a desire to seek treatment for alcohol use. At least one partner was required to meet two additional eligibility criteria. First, this individual had to report consumption of an average of at least five (for men) or four (for women) alcoholic beverages per occasion at least twice per month during the past year. Second, this individual had to be identified as perpetrating psychological or physical IPV toward their current partner via self- or partner-report on the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Bony-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996).

Upon arrival to the laboratory, inclusion criteria were reassessed. Thirteen couples failed to provide alcohol use data and were excluded from the current analyses, resulting in a total sample of 289 couples (N = 578). Site 1 enrolled 177 (61.2%) of the couples in the current study, with the remaining 112 (38.8%) couples enrolled at Site 2. This left a final sample of 578 men (age M = 33.42, SD = 10.39) and women (age M = 31.66, SD = 10.07). The average relationship had lasted 4.60 (SD = 4.70) years. Fifteen percent of participants were married. Most participants self-identified as African American (63.3%) or Caucasian (27.5%). Participants had an average of 13.99 (SD = 2.75) years of education and on average earned between $10,000 and $20,000 a year. Men reported consuming an average of 5.56 (SD = 3.49) alcoholic drinks per drinking day approximately 2.85 (SD = 2.00) days per week. Women reported consuming an average of 4.42 (SD = 3.24) alcoholic drinks per drinking day approximately 2.09 (SD = 1.83) days per week. Participants were compensated $10 per hour. This study was approved by each university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographic Form

This form obtains information such as age, self-identified sexual orientation, race, relationship status, years of education, and yearly family income.

Revised Conflict Tactics Scale

(CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Bony-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). The CTS-2 is a 78-item self-report instrument that measures a range of events that occur during disagreements within intimate relationships. Participants are instructed to indicate on a seven-point scale how many times they have engaged in these behaviors over the past year. The total number of self-reported acts of IPV perpetration on the Physical Assault subscale of the CTS-2 served as the primary outcome of interest in all analyses. Responses may range from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times), and the frequency of physical aggression is calculated by adding the midpoints of the score range for each item to form a total score. For example, if a participant indicates a response of “3–5” times in the past year, a score of “4” would be assigned. This method of scoring the CTS-2 permits examination of the frequency of different aggressive acts. Sample items include “I have thrown something at my partner that could hurt” and “I choked my partner.”

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test

(AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001). The AUDIT is a 10-item Likert-type scale developed as a screening measure for hazardous and harmful patterns of alcohol consumption. Participants rate items on a 0 to 4 scale, with higher scores indicative of greater problematic drinking. Both members of the dyad reported on their own alcohol use. Consistent with scoring procedures, participants were dichotomized to reflect the presence, as defined by an AUDIT total score of eight or more, or absence of problematic drinking. A score > 8 indicates problematic drinking with high sensitivity and specificity (Saunders, Aasland, Amundsen, & Grant, 1993). Sample items include “how often during the past year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of drinking,” and “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol.” The AUDIT has high internal consistency across a range of samples (Babor et al., 2011), which is consistent with the current sample (α = .85).

UPPS-P

(Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). The UPPS-P is a 59-item self-report measure developed to measure five impulsivity-related traits: Positive Urgency, Negative Urgency, Lack of Premeditation, Lack of Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking. Participants rate items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale, with higher scores indicating greater impulsive tendencies. These subscales have good psychometric properties (α = .82–.95), which is consistent with the current sample (α = .81–.93).

Procedures

Upon the couple’s arrival to the laboratory, each participant was led to a private testing room. After providing informed consent, participants completed the questionnaire battery on a computer using MediaLab 2006 software (Jarvis, 2006). In order to disguise the true aims of the study, additional questionnaires not pertinent to the present aims were administered. The experimenter provided instructions on how to operate the computer program and was available to answer any questions during the session. After completion of the questionnaire battery, participants were debriefed, compensated, and thanked for their time.

Data Analysis

To examine the effects of individual impulsivity facets on the perpetration of physical IPV, as well as the potential moderating effects of problematic drinking on these associations, we estimated parallel multilevel models in which individuals at Level 1 were nested under couples at Level 2 (Laurenceau & Bolger, 2005) within the APIM framework (Kenny et al., 2006) using the SPSS Mixed procedure. APIM assumes that each participant’s outcome may be influenced by the participant’s own behavior (Actor) as well as his or her partner’s behavior (Partner) and is, therefore, uniquely well suited for non-independent dyadic data. Initial analyses revealed a consistent effect of gender on physical IPV, such that, on average, female Actors reported greater physical IPV perpetration than male Actors. Formal tests of distinguishability, however, revealed that effects within dyads were not systematically identifiable by gender (see Kenny et al., 2006) and coefficients were pooled across gender as is consistent with recommended practices (Kashy & Donnellan, 2012). Significant differences also emerged in the average number of physical IPV acts reported by participants at the two sites. As a result, both gender and site were effect coded and entered as control variables in all models.

Five separate models were constructed to predict physical IPV perpetration using continuous, grand-mean centered Actor and Partner impulsivity facet scores derived from responses to the UPPS-P. Each model also included effect coded variables representing Actor and Partner problematic drinking as main effects and potential moderators of the relationship between the individual impulsivity facets and physical IPV. With highly skewed, non-normal IPV outcome data, models were estimated using a Poisson distribution with a logit link function. The initial full models, including all ten two-way and four three-way interactions, were explored first and trimmed for the purposes of parsimony, model stability, and hypothesis testing. The interaction between Actor impulsivity and Partner alcohol problems demonstrated significance or a trend towards significance in three models and was interpreted using simple slopes analyses with extreme values of continuous variables set at 0.5 standard deviations above and below the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). Fixed effects were used to model all predictors. Intercepts and error components were allowed to vary randomly. Event rate ratios (ERR) for Poisson distributed analyses were computed for all analyses. The ERR is an index of effect size that, like incident rate ratios (Swartout, Thompson, Koss, & Su, 2015) and odds ratios, represents the percentage of change in physical IPV associated with each 1 unit increase in the specified independent variable. Although ERR has been extensively used in the literature (e.g., Babson, Boden, & Bonn-Miller, 2013; Crane et al., 2014), it is important to note that there is no conventional small, medium, and large effect size cut offs for this metric. Instead, the clinical significance of a given ERR is based upon the behavior in question and the potential consequences of that behavior in context.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Male participants were, on average, older than females at the time of participation. Gender differences on key variables are presented in Table 1. More males (51.2%) than females (34.3%) reported problematic drinking [χ2 (1) = 16.97, p < .001]. At least one episode of physical or psychological IPV was detected among 295 (97.7%) couples within the current sample1. Psychological IPV was reported by 294 (97.4%) couples. Physical IPV was reported by 197 (65.2%) couples. Self-reported IPV victimization and perpetration was denied by 339 participants (56.1%) and 325 participants (53.8%), respectively. Estimates of the number of acts of Actor-reported physical IPV (M = 4.24, SD = 16.95) ranged from zero to 300 and totals underwent Winsorization at 4 standard deviations to minimize the effects of the five greatest outliers. Relying upon Actor self-report, approximately 39.1% of couples evidenced nonviolent behavior, 12.1% reported male-to-female only IPV, 16.3% reported female-to-male only IPV, and 31.8% reported concordant physical IPV perpetration. When present, male perpetration was significantly greater among IPV concordant (M = 6.96, SD = 9.07), rather than discordant (M = 3.0, SD = 1.93), couples [t(125) = −2.55, p = .01]. When present, female perpetration was comparable among IPV concordant (M = 9.86, SD = 14.68) and discordant (M = 7.85, SD = 14.57) couples [t(137)= −.765, p = .45]. Gender differences on key variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive and bivariate relationships for age, education, and impulsivity among male and female couple members

| Full Sample (N = 578)

|

Males (n = 289)

|

Females (n= 289)

|

t | df | p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| 1. Physical IPV (acts) | .28* | .25* | .09** | .13* | .01 | 2.62 | 6.04 | 4.45 | 11.15 | 2.45** | 574 | .02 |

| 2. Negative Urgency | .75* | .34* | .46* | .12* | 2.15 | 0.63 | 2.15 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 575 | .88 | |

| 3. Positive Urgency | .25* | .37* | .17* | 1.81 | 0.63 | 1.71 | 0.61 | −1.89† | 575 | .06 | ||

| 4. Lack of Premeditation | .58* | .18* | 1.73 | 0.43 | 1.75 | 0.46 | 0.74 | 575 | .46 | |||

| 5. Lack of Perseverance | −.03 | 1.64 | 0.42 | 1.69 | 0.47 | 1.36 | 575 | .17 | ||||

| 6. Sensation Seeking | 2.68 | 0.61 | 2.42 | 0.60 | −5.27* | 575 | <.001 | |||||

| Age (years) | 33.42 | 10.34 | 31.66 | 10.07 | −2.07** | 576 | .04 | |||||

| Education (years) | 13.74 | 2.74 | 14.24 | 2.74 | 2.17** | 568 | .03 | |||||

Note: IPV = Intimate partner violence.

p <.01,

p <.05,

p <.10

APIM Analyses

Negative Urgency

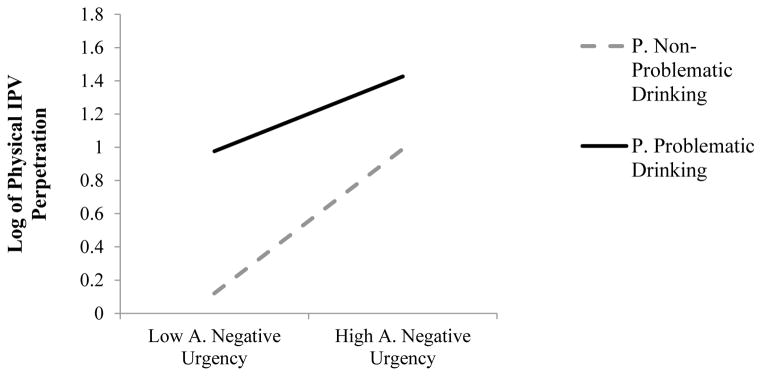

The first model estimated the effects of the Actor’s negative urgency and problematic drinking on his or her own physical IPV perpetration, and the effects of the Partner’s negative urgency and problematic drinking on the Actor’s physical IPV perpetration. As can be seen in Table 2, significant main effects were detected for Actor problematic drinking and Partner negative urgency, indicating that Actors with problematic drinking reported perpetrating, on average, approximately thirty percent more acts of physical IPV than Actors without problematic drinking and that each unit increase in Partner negative urgency was associated with a 38% increase in Actor physical IPV. Significant Actor negative urgency and Partner problematic drinking main effects were qualified by their interaction term. Interpretation of the interaction using simple slopes analysis revealed that Actor negative urgency was significantly and positively associated with Actor physical IPV when Partners reported no problematic drinking (b = 1.37, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.93 – 1.80, ERR = 3.94). This association was still significant, but weaker, among Actors whose partners reported problematic drinking (b = 0.71, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.37 – 1.04, ERR = 2.03). As depicted in Figure 1, this interaction was largely driven by individuals who endorsed lower levels of negative urgency reporting significantly higher levels of physical IPV perpetration toward a problematic drinking partner relative to a non-problematic drinking partner (b = 0.86, p = .002, 95% CI = 0.31 – 1.41, ERR = 2.35). As indicated by the ERR, low negative urgency Actors had a rate of Actor physical IPV that was 2.35 times higher toward problematic drinking partners than toward non-problematic drinking partners, holding all other variables in the model constant.

Table 2.

Results for five parallel multi-level models of individual impulsivity facets and problematic drinking predicting intimate partner violence perpetration

| b | SE | p | 95% CI

|

ERR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Negative Urgency | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.88* | .11 | <.001 | 0.66 | 1.09 | 2.41 |

| Actor Drinking | 0.26* | .10 | .006 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 1.30 |

| Partner Drinking | 0.32* | .11 | .004 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 1.38 |

| Actor Impulsivity | 1.04* | .14 | <.001 | 0.76 | 1.32 | 2.83 |

| Partner Impulsivity | 0.32** | .14 | .018 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 1.38 |

| Actor Impulsivity X Partner Drinking | −0.33** | .14 | .016 | −0.60 | −0.06 | 0.72 |

| Positive Urgency | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.02* | .10 | <.001 | 0.83 | 1.21 | 2.77 |

| Actor Drinking | 0.31* | .10 | .002 | 0.11 | 0.50 | 1.36 |

| Partner Drinking | 0.44* | .11 | <.001 | 0.23 | 0.65 | 1.55 |

| Actor Impulsivity | 0.75* | .13 | <.001 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 2.12 |

| Partner Impulsivity | −0.09 | .14 | .530 | −0.35 | 0.18 | 0.91 |

| Actor Impulsivity X Partner Drinking | −0.29** | .12 | .015 | −0.52 | −0.06 | 0.75 |

| Lack of Premeditation | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.11* | .10 | <.001 | 0.92 | 1.30 | 3.03 |

| Actor Drinking | 0.44* | .10 | <.001 | 0.25 | 0.64 | 1.55 |

| Partner Drinking | 0.36* | .10 | <.001 | 0.17 | 0.56 | 1.43 |

| Actor Impulsivity | −0.01 | .21 | .956 | −0.42 | 0.40 | 0.99 |

| Partner Impulsivity | 0.09 | .18 | .619 | −0.27 | 0.45 | 1.09 |

| Actor Impulsivity X Partner Drinking | 0.38† | .20 | .064 | −0.02 | 0.78 | 1.46 |

| Lack of Perseverance | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.08* | .10 | <.001 | 0.88 | 1.28 | 2.94 |

| Actor Drinking | 0.43* | .10 | <.001 | 0.23 | 0.63 | 1.54 |

| Partner Drinking | 0.33* | .10 | .001 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 1.39 |

| Actor Impulsivity | 0.42** | .19 | .031 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 1.52 |

| Partner Impulsivity | 0.40** | .19 | .038 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 1.49 |

| Actor Impulsivity X Partner Drinking | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Sensation Seeking | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.11* | .10 | <.001 | 0.92 | 1.30 | 3.03 |

| Actor Drinking | 0.45* | .10 | <.001 | 0.25 | 0.64 | 1.57 |

| Partner Drinking | 0.39* | .10 | <.001 | 0.21 | 0.58 | 1.48 |

| Actor Impulsivity | 0.23 | .15 | .109 | −0.05 | 0.52 | 1.26 |

| Partner Impulsivity | −0.30** | .14 | .035 | −0.57 | −0.02 | 0.74 |

| Actor Impulsivity X Partner Drinking | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

Note: SE = Standard Error; CI = Confidence Interval; ERR = event rate ratio for Poisson distributed analyses, representing the percentage of change in partner violence perpetration associated with each 1 unit increase in the specified independent variable; Models were estimated using a Poisson distribution with a logit link function and controlled for gender as well as assessment site.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

Figure 1.

Actor negative urgency and Partner problematic drinking predicting Actor IPV perpetration. Note: A = Actor. P = Partner. Negative urgency was graphed using − ½ standard deviation (low) and + ½ standard deviation (high). Models were estimated using a Poisson distribution with a logit link function.

Positive Urgency

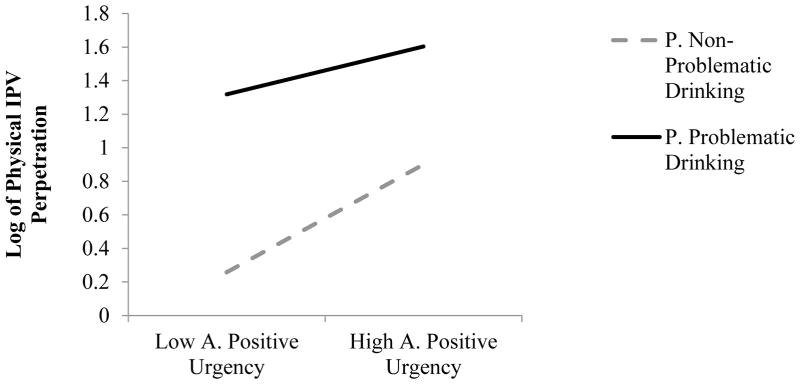

The second model estimated the effects of the Actor’s positive urgency and problematic drinking on his or her own physical IPV perpetration, and the effects of the Partner’s positive urgency and problematic drinking on the Actor’s physical IPV perpetration. As depicted in Table 2, results indicated a significant Actor problematic drinking effect as well as an interaction between Actor positive urgency and Partner problematic drinking. Examination of this effect revealed that Actor positive urgency was significantly and positively associated with Actor physical IPV perpetration when partners reported no problematic drinking (b = 1.04, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.66 – 1.42, ERR = 2.83). This effect was still significant, but weaker, among Actors whose partners reported problematic drinking (b = 0.46, p = .002, 95% CI = 0.17 – 0.78, ERR = 1.58). As depicted in Figure 2, this interaction was largely driven by individuals who endorsed lower levels of positive urgency reporting significantly higher levels of physical IPV perpetration toward a problematic drinking partner relative to a non-problematic drinking partner (b = 1.06, p < .001, 95% CI = .57 – 1.56, ERR = 2.89). As indicated by the ERR, low positive urgency Actors had a rate of Actor physical IPV that was nearly three times higher toward problematic drinking partners than toward non-problematic drinking partners, holding all other variables in the model constant.

Figure 2.

Actor positive urgency and Partner problematic drinking predicting Actor IPV perpetration. Note: A = Actor. P = Partner. Positive urgency was graphed using − ½ standard deviation (low) and + ½ standard deviation (high). Models were estimated using a Poisson distribution with a logit link function.

Lack of Premeditation

The third model estimated the effects of the Actor’s lack of premeditation and problematic drinking on his or her own physical IPV perpetration, and the effects of the Partner’s lack of premeditation and problematic drinking on the Actor’s physical IPV perpetration. Results indicated a significant main effect of Actor problematic drinking and a trend toward a significant interaction between Actor lack of premeditation and Partner problematic drinking (see Table 2). Exploration of this interaction revealed that Actor lack of premeditation was associated with physical IPV when partners reported problematic drinking (b = 0.37, p = .08, 95% CI = −0.05 – 0.78, ERR = 1.45). The association was absent among Actors whose partners reported no problematic drinking (b = −0.39, p = .27, 95% CI = −1.09 – 0.31, ERR = 0.68). Partner premeditation was not associated with Actor physical IPV perpetration.

Lack of Perseverance

The fourth model estimated the effects of the Actor’s lack of perseverance and problematic drinking on his or her own physical IPV perpetration, and the effects of the Partner’s lack of perseverance and problematic drinking on the Actor’s physical IPV perpetration. As can be seen in Table 2, significant positive main effects of Actor and Partner problematic drinking as well as Actor and Partner lack of perseverance were detected. These results indicated that both members’ problematic drinking and high impulsivity on this facet were independently associated with an increased risk of physical IPV perpetration. Significant interaction effects were not detected.

Sensation Seeking

The fifth model estimated the effects of the Actor’s sensation seeking and problematic drinking on his or her own physical IPV perpetration, and the effects of the Partner’s sensation seeking and problematic drinking on the Actor’s physical IPV perpetration. Accounting for significant Actor and Partner alcohol effects, Partner sensation seeking was significantly and negatively associated with Actor physical IPV perpetration such that every unit increase in Partner sensation seeking was associated with a decrease of .74 acts of physical IPV. Actor sensation seeking was not associated with physical IPV perpetration. Significant interaction effects were not detected.

Discussion

The present study was the first to investigate the effects of problematic drinking and facets of impulsivity on physical IPV within a dyadic framework. Several important results warrant attention. First, and consistent with hypotheses, Actor alcohol problems and negative urgency were associated with physical IPV. Second, and unexpectedly, a significant association between Actor lack of perseverance and physical IPV also emerged. Third, and contrary to hypotheses, Actor problematic drinking did not moderate the effect of actor positive and negative urgency on Actor physical IPV. Fourth, findings demonstrated associations between Partner problematic drinking and Actor physical IPV as well as significant Partner Problematic Drinking x Actor Impulsivity (Negative Urgency and Positive Urgency) interaction effects on Actor physical IPV. Given the dearth of research accounting for the dyadic context of IPV, a priori predictions regarding the effect of Partner problematic drinking and impulsivity on Actor physical IPV were not appropriate. Nevertheless, these findings also merit attention and are discussed below.

Actor Effects

Consistent with hypotheses, results indicated significant main effects of Actor problematic drinking on physical IPV. Of course, it is well-established that alcohol use is a contributing cause of IPV perpetration (Leonard, 2005). However, this finding is noteworthy because it remained robust across five parallel multi-level models within the actor-partner framework. Also in line with hypotheses and prior research (Derefinko et al., 2011), results demonstrated a significant main effect of Actor negative urgency on physical IPV. This finding indicates that the inability to resist impulses under conditions of negative affect is associated with physical IPV perpetration. Importantly, the present sample was comprised of couples who may be defined as high risk by virtue of their patterns of heavy drinking and relationship conflict. The relatively high level of conflict and concomitant negative affect in these couples represents the necessary conditions for high levels of negative urgency to facilitate physical IPV. Indeed, the I3 meta-theoretical model suggests that inhibiting influences, such as one’s capacity to regulate impulses, are critical determinants of an individual’s ability to resist urges toward aggressive behavior (Finkel, 2007) and this may require the ability to regulate negative affect (Berkowitz, 1990). Consistent with this view, a daily-diary study demonstrated that husbands’ negative affect predicted IPV perpetration among men whose wives reported perpetrating IPV in the past year, but not among wives’ who did not (McNulty & Hellmuth, 2008). Coupled with the present data, one’s ability to regulate negative affect is likely a key determinant of physical IPV, particularly in couples with a high degree of relationship conflict.

Though not predicted, a significant association was found between Actor lack of perseverance and physical IPV. This finding is somewhat perplexing given that prior research has yet to demonstrate an association between this facet of impulsivity and a range of aggressive behaviors, including IPV (Derefinko et al., 2011). Though tentative, one possible explanation is predicated on the notion that lack of perseverance refers to an individual’s tendency to lose focus or lack persistence during mundane tasks. Given that couples in this sample were characterized by high relationship conflict, including high rates of psychological IPV, the difficulty to focus or persist may derail these individuals’ sustained attempts to implement adaptive coping strategies during conflict situations. As a result, individuals who endorse a lack of perseverance may derail attempts at inhibitory control and perpetrate physical IPV more frequently.

Alcohol facilitates aggression to a greater extent among individuals who are predisposed to behave aggressively (Collins, Schlenger, & Jordan, 1988; Fishbein, 1998; Pernanen, 1991). Research that assesses aggression toward intimates and non-intimates supports this view (e.g., Eckhardt & Crane, 2008; Heyman, O’Leary, & Jouriles, 1995; Miller, Parrott, & Giancola, 2009). Of particular relevance to the present study, studies indicate that the alcohol-IPV relation is stronger among individuals who report higher, relative to lower, levels of impulsivity (Schumacher et al., 2013; Watkins et al., 2014). Contrary to this literature, the present findings failed to detect an interaction between Actor problematic drinking and Actor impulsivity; rather, results indicate that Actor problematic drinking is associated with IPV across levels of Actor impulsivity. Explanations for this finding’s divergence from extant literature may be due to sampling and analytic differences across these studies. Unlike a prior study which examined heavy drinking, impulsivity, and IPV in a college sample (Watkins et al., 2014), the present study utilized a high-risk community sample of heavy drinking men and women. Although Schumacher and colleagues (2013) utilized a sample of heavy drinking men, this study did not examine this link in women or account for any potential partner effects. Taken together, these data suggest that in couples characterized by patterns of heavy drinking and relationship conflict, additional individual risk factors (e.g., impulsivity) may not increase heavy drinking men and women’s frequency of IPV. It is clear that the effect of problematic drinking on physical IPV may differ as a function of the nature of the relationship; however, more research is needed to confirm these findings and more accurately inform treatment programs.

Actor and Partner Effects

Because research has not examined the alcohol-IPV relation within a dyadic framework (for exceptions, see Crane et al, 2014, Testa et al., 2012; Testa & Derrick, 2014; Watkins et al., 2014; Woodin et al, 2014), there was little empirical basis to advance specific hypotheses for partner effects and actor-partner interaction effects. That stated, the most important contribution of the present study arguably comes from analysis of these effects, which provide insight into how Actor and Partner factors independently and jointly interact to predict physical IPV. Results indicate that Partner negative urgency is positively associated with Actor IPV perpetration. This finding suggests that one’s inability to resist impulses under conditions of negative affect is associated with more frequent physical IPV victimization. Additionally, results demonstrated that Partner sensation seeking is negatively associated with Actor IPV perpetration. This finding is puzzling, as it is difficult to speculate why one’s inclination to pursue activities that are arousing is associated with less IPV victimization. As such, more research is needed to elucidate this effect.

Results indicate that Partner problematic drinking is associated with Actor IPV perpetration. This is consistent with prior research that suggests alcohol consumption is associated with greater IPV victimization (Devries et al., 2014). This Partner effect is further characterized by its interaction with Actor positive and negative urgency. Not surprisingly, the highest levels of physical IPV were observed among Actors with high urgency whose partners were problematic drinkers. However, these interaction effects were driven primarily by more frequent perpetration of physical IPV by Actors with low urgency who had problematic drinking, relative to non-problematic drinking, partners. This effect was substantial, as the rate of physical IPV among low urgency Actors was 2–3 times higher toward problematic drinking partners than toward non-problematic drinking partners. Again, couples in the present study were characterized by a high level of relationship conflict and heavy drinking. As such, the relatively high level of conflict and concomitant affect in these couples represents the necessary conditions for high levels of negative and positive urgency to facilitate physical IPV. Though distinct facets of impulsive behavior, research suggests a strong association between positive and negative urgency, or the tendency or act rashly in response to positive and negative affect, respectively (Cyders et al., 2007). Perhaps this is because the tendency to act rashly in response to extreme emotional states may reflect an underlying dysfunction in one’s ability to regulate emotions (Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith 2009).

Interpreted within an I3 framework, in these high risk couples, individuals low in urgency with non-problematic drinking partners may possess sufficient self-regularly capacity to inhibit aggressive urges in affect-laden situations; in essence, these individuals’ inhibitory control is stronger than the collective influence of instigatory (e.g., relationship conflict) and impellance (e.g., high anger arousal) factors (Eckhardt, Parrott, & Sprunger, 2015). However, a partner’s problematic drinking may lead to additional instigatory factors that “tip the balance” and thus push these individuals over their aggression threshold (Sprunger, Eckhardt, & Parrott, 2015). For instance, a partner’s heavy drinking can elicit greater relationship conflict and facilitate their partner’s (i.e., actor) perpetration of more frequent and intense IPV (e.g., Testa et al., 2012; Woodin et al., 2014). As a result, actors are more regularly exposed to stronger provocation cues. Collectively, these findings suggest that the lowest risk of IPV perpetration exists in couples comprised of Actors with low impulsivity and Partners with no alcohol problems. However, existence of either factor is sufficient to increase IPV perpetration. It is important to note that Actor problematic drinking did not interact with Partner impulsivity. This is likely because alcohol is a more powerful disinhibiting factor that facilitates IPV regardless of an individual’s, or their partner’s impulsive tendencies. However, Partner problematic drinking appears to play an important role in IPV by fueling relationship conflict.

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, temporal or causal conclusions about the variables under investigation cannot be confirmed and should be considered tentative. As such, there is no way of knowing whether individuals, or their partners, were intoxicated during the time of the assault, or if physical IPV was motivated by impulsive tendencies. Future research is needed to disentangle the direct and indirect effects of problematic drinking on IPV within a relational context and may be addressed with laboratory- (Eckhardt et al., 2015) or event-based studies (e.g., Testa & Derrick, 2014) which are designed to isolate these links. Second, a strength of the present investigation was the examination of actor-partner effects within heterosexual couples characterized by high relationship conflict, wherein at least one member was a heavy drinker. That stated, it remains to be seen whether the present findings generalize to lower-risk couples (e.g., lower conflict, non-heavy drinking) or same-sex couples. Moreover, given that the majority of the sample was not married, it is unclear the extent to which these findings apply to married or long-term cohabitating couples.

Limitations notwithstanding, the present study makes an important contribution to the current literature base by providing new insight into how Actor and Partner problematic drinking and distinct facets of impulsivity independently and jointly interact to predict physical IPV in high risk heterosexual couples. Indeed, IPV does not occur in a vacuum, but rather is part of a greater relationship context that is inherently interactional and comprised of both partners’ dispositions (e.g., Bartholomew & Cobb, 2010). Findings suggest that treatment programs for IPV may benefit from an emphasis on both partners’ problematic drinking and on perpetrators’ impulse control difficulties, particularly among couples characterized by a high level of relationship conflict. However, there remains limited evidence from which to explain the effects of partner characteristics on IPV. Results highlight the need to examine IPV within a dyadic framework to better elucidate risk factors for prevention and intervention efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01-AA-020578 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to the 3rd and 4th authors.

Footnotes

In order to participate in the present study, at least one member of the couple had to be identified as perpetrating psychological or physical IPV toward their current partner via self- or partner-report on the telephone screen. Upon arrival to the laboratory, 2.3% of couples denied any IPV. All analyses are based on the full sample; however, when couples who denied any IPV when assessed in the laboratory were removed from analyses, only a slight attenuation of estimates was observed with no change in the direction or significance of the reported effects.

Contributor Information

Ruschelle M. Leone, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University

Cory A. Crane, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology

Dominic J. Parrott, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University

Christopher I. Eckhardt, Department of Psychology, Purdue University

References

- Abbey A, Clinton AM, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Buck PO. Alcohol-involved rapes: Are they more violent? Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2002;26(2):99–109. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- Babson KA, Boden MT, Bonn-Miller MO. The impact of perceived sleep quality and sleep efficiency/duration on cannabis use during a self-guided quit attempt. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2707–2713. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnwell SS, Borders A, Earleywine M. Alcohol-aggression expectancies and dispositional aggression moderate the relationship between alcohol consumption and alcohol-related violence. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32(6):517–527. doi: 10.1002/ab.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Cobb R. Conceptualizing relationship violence as a dyadic process. In: Horowitz LM, Strack S, editors. Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walter ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, Stevens MR. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Cooper HM. Effects of alcohol on human aggression: An integrative research review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(3):341–354. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3(2):231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental system perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsoff WM, Lebow JL, editors. Family psychology: The art of the science. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JB, Dickow A, Horner K, Zweben JE, Balabis J, Vandersloot D, Reiber C. Abuse and violence history of men and women in treatment for methamphetamine dependence. American Journal on Addictions. 2003;12(5):377–385. doi: 10.1080/10550490390240701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, Schlenger WE, Jordan BK. Antisocial personality and substance abuse disorders. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry & the Law. 1988;16(2):187–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Schlauch RC, Hawes SW, Mandel DL, Easton CJ. Legal factors associated with change in alcohol use and partner violence among offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;47:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M, Derrick JL, Leonard KE. Daily associations among self-control, heavy episodic drinking, and relationship functioning: An examination of actor and partner effects. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40(5):440–450. doi: 10.1002/ab.21533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Ames GM, Duke M. The relationship of alcohol problems to risk for unidirectional and bidirectional intimate partner violence among a sample of blue-collar couples. Violence and Victims. 2011;26(2):147–158. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Todd M, Dukes M, Ames GM. Problem drinking, unemployment, and intimate partner violence among a sample of construction industry workers and their partners. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24(2):63–74. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9209-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Pedersen WC, Friese M, Hahm A, Roberts L. Understanding impulsive aggression: Angry rumination and reduced self-control capacity are mechanisms underlying the provocation-aggression relationship. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37(6):850–862. doi: 10.1177/0146167211401420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derefinko K, DeWall CN, Metze AV, Walsh EC, Lynam DR. Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37(3):223–233. doi: 10.1002/ab.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, Mak J, Falder G, Graham K, Watts C, Heise L. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109(3):379–391. doi: 10.1111/add.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, Sher K. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology. 2010;15(2):217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Crane C. Effects of alcohol intoxication and aggressivity on aggressive verbalizations during anger arousal. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34(4):428–436. doi: 10.1002/ab.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Parrott DJ, Sprunger JG. Mechanisms of alcohol-facilitated intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(8):939–957. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ. Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology. 2007;11(2):193–207. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.11.2.193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Eckhardt CI. Intimate partner violence. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships. New York: Oxford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, DeWall CN, Slotter EB, Oaten M, Foshee VA. Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(3):483–499. doi: 10.1037/a0015433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein DH. Differential susceptibility to comorbid drug abuse and violence. Journal of Drug Issues. 1998;28(4):859–890. [Google Scholar]

- Foran MH, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KE, Parrott DJ. Influence of heavy episodic drinking on the relation between men’s locus of control and aggression toward intimate partners. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(2):299–306. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KE, Parrott DJ. Influence of heavy episodic drinking on the relation between men’s locus of control and aggression toward intimate partners. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(2):299–306. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive functioning and alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(4):541–555. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Parrott DJ, Duke AA. Alcohol myopia revisited clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5(3):265–278. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(6):598–607. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wells S, West P. A framework for applying explanations for alcohol-related aggression to naturally occurring aggressive behavior. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1997;24:625–666. [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, O’Leary KD, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: Potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives? Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9(1):44–57. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.9.1.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hynan DJ, Grush JE. Effects of impulsivity, depression, provocation, and time on aggressive behavior. Journal of Research in Personality. 1986;20(2):158–171. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(86)90115-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis BG. DirectRT (Version 2006) [Computer software] New York, NY: Empirisoft Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jose A, O’Leary KD. Prevalence of partner aggression in representative and clinic samples. In: O’Leary KD, Woodin EM, editors. Psychological and physical aggression in couples: Causes and interventions. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Donnellan MB. Conceptual and methodological issues in the analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Deaux K, Snyder M, editors. The Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 209–238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Cook WL. Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships. 1999;6(4):433–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00202.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Kashy D, Cook W. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Bolger N. Using diary methods to study marital and family processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(1):86–97. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: When can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence? Addiction. 2005;100(4):422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, Cyders MA. Tech Rep. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University; 2006. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Hellmuth JC. Emotion regulation and intimate partner violence in newlyweds. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(5):794–797. doi: 10.1037/a0013516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Parrott DJ, Giancola PR. Agreeableness and alcohol-related aggression: The mediating effect of trait aggressivity. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17(6):445–455. doi: 10.1037/a0017727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(8):1403–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00122-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Netter P, Hennig J, Rohrmann S, Wyhlidal K, Hain-Hermann M. Modification of experimentally induced aggression by temperament dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;25(5):873–888. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00070-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K, Smith Slep AM, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of men’s and women’s partner aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(5):752–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernanen K. Alcohol in human violence. New York, NY: Guilford; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Amundsen A, Grant M. Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction. 1993;88(3):349–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Cunradi CB. A path model of risk factors for intimate partner violence among couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(2):127–142. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Leonard KE, O’Jile JR, Landy NC. Self-regulation, daily drinking, and partner violence in alcohol treatment-seeking men. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(1):17–28. doi: 10.1037/a0031141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JP, DiLillo D, Maldonado RC, Watkins LE. Negative urgency and emotion regulation strategy use: Associations with displaced aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2015;41(5):502–512. doi: 10.1002/ab.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Combs JL, Gunn RL, Smith GT. Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):160–172. doi: 10.1037/a0024948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, Stuart GL. The association between impulsivity, trait anger, and the perpetration of intimate partner violence and general violence among women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(13):2681–2697. doi: 10.1177/0886260510388289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(2):236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0024855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprunger JG, Eckhardt CI, Parrott DJ. Anger, problematic alcohol use, and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2015;25(4):273–286. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45(8):921–933. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10(1):65–98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss MA, Gelles RJ. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Testing a theoretical model of the relationship between impulsivity, mediating variables, and husband violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20(5):291–303. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-6605-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swartout, Thompson, Koss, Su What is the best way to analyze less frequent forms of violence? The case of sexual aggression. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5:305–313. doi: 10.1037/a0038316. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Derrick JL. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Kubiak A, Quigley BM, Houston RJ, Derrick JL, Levitt A, Homish GG, Leonard KE. Husband and wife alcohol use as independent or interactive predictors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(2):268–276. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Does alcohol make a difference? Within-participants comparison of incidents of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(7):735–743. doi: 10.1177/0886260503252323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LE, Maldonado RC, DiLillo D. Hazardous alcohol use and intimate partner aggression among dating couples: The role of impulse control difficulties. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40(4):369–381. doi: 10.1002/ab.21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LE, DiLillo D, Maldonado RC. The interactive effects of emotion regulation and alcohol intoxication on lab-based intimate partner aggression. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/adb0000074. in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/adb0000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodin EM, Caldeira V, Sotskova A, Galaugher T, Lu M. Harmful alcohol use as a predictor of intimate partner violence during the transition to parenthood: Interdependent and interaction effects. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(12):1890–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]