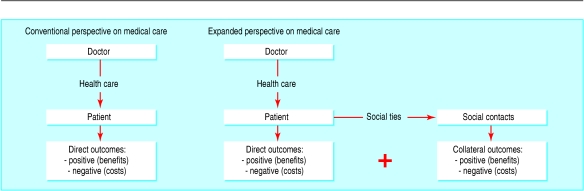

Since a patient or a clinical trial participant is connected to other people through social network ties, medical interventions delivered to a patient, quite apart from their health effects in that person, may have unintended health effects in others to whom he is connected. The cumulative impact of an intervention is therefore the sum of the direct health outcomes in the patient plus the collateral health outcomes in others (figure). These effects, in both the patient and in their social contacts, might be positive or negative. Doctors, trialists, patients, or policy makers might see reason to take them into account when choosing treatment or evaluating benefit.

Figure 1.

Collateral health effects of medical care in social networks. In the conventional perspective on medical care, the benefits and costs of health care are judged by the way in which they help to achieve a direct, intended outcome in a patient. However, since a patient is connected to others through social ties, health care delivered to one person, quite apart from its health effects on that person, may have health effects on others. The cumulative impact of the intervention is therefore a sum of the direct outcomes in the patient plus the collateral outcomes in others. These outcomes may be both positive and negative in both the patient and in his or her social contacts (for example, side effects of medication in the individual, herd immunity in social contacts). Attention to, and measurement of, the existence of unintended outcomes arising out of the embeddedness of patients in social networks can prompt a rethinking of the relative value of healthcare interventions or of the conduct of clinical trials.

For example, treating depression in parents may increase their propensity to vaccinate their children, thereby saving children's lives. Replacing a hip or preventing a stroke may mean that a person is better able to care for his spouse, thus improving her health. Delivering a weight loss intervention to one person may trigger substantial weight loss in that person's friends. Giving a patient superior end of life care may decrease the stressfulness of the patient's death and thus decrease his spouse's propensity to die during bereavement.1

These collateral health consequences that accrue to others are known to social scientists as externalities. They are similar to the increase in value a person's neighbour may see if the person refurbishes his property; the person himself derives no benefit from the neighbour's windfall, even though he has invested resources and created this new value. Here, however, we are considering not monetary externalities but rather specifically health externalities. Moreover, in the healthcare arena patients may derive value from such effects. For example, since 89% of patients feel that a good death involves not burdening family,2 patients might prefer hospice care over standard terminal care if they felt it offered health benefits to their loved ones.1

When the cost-benefit assessment is made by policy makers with a collective viewpoint, all the downstream costs and benefits of health care accruing to a group might be relevant, and the argument in favour of accounting for collateral effects might be even more compelling than that perceived by individual doctors or patients. From a societal perspective the assessment of the cost effectiveness of medical interventions might change substantially if the benefits of an intervention are seen as including the collateral positive effects and the costs as including the collateral negative effects.

Such a concern for collateral effects could, however, also lead to unexpected results. For example, preventing a death from heart attack, which is clearly desirable from the individual's perspective, may mean that we have to forego the motivation that would otherwise have accrued to others to whom the patient is connected to improve their own health habits. Another provocative implication is that policy makers might value socially connected individuals—such as married people—more when it comes to health care since benefits might be multiplicative in such people.3

We have scattered evidence supporting the plausibility and likely magnitude of such collateral health effects. The most well known example is that the death of one spouse increases the risk of death in the other.4,5 Moreover, morbidity in one spouse can contribute to morbidity in the other—for example, via caregiver burden.6 Breast cancer in one woman may motivate others to whom she is connected to have mammography.7 Exercise or smoking cessation in one person may prompt numerous others to behave similarly. Conversely, there may be epidemics of disorders such as obesity, alcoholism, suicide, or depression that might spread in a peer to peer fashion.8 Even loose social connections can be conduits for such effects; cancer in a celebrity, for example, may motivate many people not known to the index case to undergo cancer screening or choose particular treatments.9,10 Vaccinating some people in a population may cause others (for example, immunocompromised people) to become sick through the spread of the vaccine virus or, conversely, to remain well through the effect of herd immunity.

The existence of collateral health effects and the fact that each individual may be connected to numerous others, including relatives, friends, neighbours, and co-workers, implies developments in research and policy. To explore such effects, new datasets and methods will be needed. Most prospective cohort studies and randomised controlled trials today include only individuals who are followed to observe outcomes. Some social science and epidemiological cohort studies do ask individuals about the health status of their spouse or some other social contact, but only a few (for example, the US health and retirement survey) actually include the spouse or other social contacts in the study cohort. Developing datasets with such features and measurements is necessary to understand fully collateral health effects. Collecting information about the various contacts of people enrolled in clinical trials or epidemiological studies may represent an extension to study design similar to the extension in the 1990s of including cost effectiveness analyses as a standard feature of clinical trials.

Network phenomena are receiving increased attention in fields as diverse as engineering, biology, and sociology,11,12 but they are also relevant to health and medicine. Networks have emergent properties not explained by the constituent parts and not present in the parts. Understanding such properties requires seeing whole groups of individuals and their interconnections at once. The existence of social networks means that people and events are interdependent and that health and health care can transcend the individual in ways that patients, doctors, policy makers, and researchers should care about.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact on families of health care: a matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med 2003;57: 465-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284: 2476-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D Crane. The sanctity of social life: physicians' treatment of critically ill patients. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1990.

- 4.Schaefer C, Quesenberry CP, Soora W. Mortality following conjugal bereavement and the effects of a shared environment. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141: 1142-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lillard LA, Waite LJ. `Til death do us part: marital disruption and mortality. Am J Sociol 1995;100: 1131-56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA, 1999;282: 2215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murabito JM, Evans JC, Larson MG, Kreger BE, Splansky GL, Mutalik KM, et al. Family breast cancer history and mammography. Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154: 916-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews JA. Tildesley E. Hops H. Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychol 2002;21: 349-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nattinger AB, Hoffmann RG, Howell-Pelz A, Goodwin JS. Effect of Nancy Regan's mastectomy on choice of surgery for breast cancer by US women. N Engl J Med 1998;279: 762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cram P, Fendrick M, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med 2003;163: 1601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.B Wellman, SD Berkowitz. Social structures: a network approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- 12.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of “Small World” networks. Nature 1998;393: 440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]