Abstract

Purpose

Provide 2-year efficacy, safety and treatment results comparing three anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents for center-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) utilizing a standardized follow-up and retreatment regimen.

Design

Randomized clinical trial.

Participants

660 participants with DME causing visual acuity (VA) impairment.

Methods

Randomization to 2.0-mg aflibercept, 1.25-mg repackaged (compounded) bevacizumab, or 0.3-mg ranibizumab intravitreous injections performed as frequently as monthly utilizing a protocol-specific follow-up and retreatment regimen. Focal/grid laser was added if DME persisted and was not improving at 6 months or later. Visits occurred every 4 weeks during year 1, and were extended up to every 4 months thereafter when VA and macular thickness were stable and injections were deferred.

Main Outcome Measures

Change in VA (efficacy), ocular/systemic adverse events (safety), retreatment frequency.

Results

Median numbers of injections in year 2 were 5, 6, 6 and over 2 years were 15, 16, 15 in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively (global P=0.08). Focal/grid laser was administered in 41%, 64%, and 52%, respectively (aflibercept-bevacizumab: P<0.001, aflibercept-ranibizumab: P=0.04, bevacizumab-ranibizumab: P=0.01). From baseline to 2 years, mean VA letter score improved by 12.8 with aflibercept, 10.0 with bevacizumab, and 12.3 with ranibizumab. Treatment group differences varied by baseline VA (interaction P=0.02). With worse baseline VA (20/50-20/320), mean improvement was 18.3, 13.3, and 16.1 letters, respectively (aflibercept-bevacizumab: P=0.02, aflibercept-ranibizumab: P=0.18, ranibizumab-bevacizumab: P=0.18). With baseline VA 20/32-20/40, mean improvement was 7.8, 6.8, and 8.6 letters, respectively (P>0.10 for pairwise comparisons). Anti-Platelet Trialists’ Collaboration (APTC) events occurred in 5% with aflibercept, 8% with bevacizumab, and 12% with ranibizumab (global P=0.047: aflibercept-bevacizumab: P=0.34, aflibercept-ranibizumab: P=0.047, ranibizumab-bevacizumab: P=0.20; global P=0.09 adjusted for potential confounders).

Conclusion

All 3 anti-VEGF groups had visual acuity improvement at 2 years with a decreased number of injections in year 2. VA outcomes were similar among treatment groups for eyes with baseline VA 20/32-20/40. Among eyes with worse baseline VA, aflibercept, on average, had superior 2-year VA outcomes compared with bevacizumab, but superiority of aflibercept over ranibizumab, noted at 1 year, was no longer identified. Higher APTC event rates with ranibizumab over 2 years warrants continued evaluation in future trials.

Introduction

The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) conducted a comparative effectiveness trial comparing the three commonly used anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents, aflibercept (EYLEA®, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech), and ranibizumab (Lucentis®, Genentech) for center-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) associated with visual impairment. The study utilized a standardized follow-up and retreatment regimen, including focal/grid laser for persistent DME not improving 6 months or later. The previously reported 1-year results showed all three agents improved vision, on average, with treatment group differences varying according to initial visual acuity.1, 2 When baseline visual acuity impairment was mild (20/32 to 20/40), no apparent differences in visual acuity, on average, were identified among the groups, while at worse levels of visual acuity (20/50 to 20/320), aflibercept, on average, was more effective at improving vision than the other two agents. No statistically significant differences in pre-specified ocular or systemic safety events among the 3 anti-VEGF agents were identified.

The 1-year primary outcome time point was chosen, in part, because previous trials consistently showed that, on average, most visual acuity improvement with anti-VEGF agents for DME occurred by 1 year.3-5 Therefore, we anticipated if there were treatment group differences, they likely would be apparent by 1 year. However, the secondary and final study end point at 2 years was chosen to determine if differences in treatment effects identified at 1 year were sustained at 2 years and whether differences in intravitreous injection and laser frequency were identified. The results of the 2-year analyses are reported herein.

Methods

The study procedures and statistical methods have been reported previously and are summarized briefly.2 The protocol is available on the DRCR.net website (www.drcr.net, date accessed: December 22, 2015).

Eighty-nine clinical sites enrolled 660 participants (mean age 61±10 years; 47% women) with best corrected visual acuity (approximate Snellen equivalent) of 20/32 to 20/320 (mean baseline visual acuity approximately 20/50), center-involved DME on clinical examination and optical coherence tomography (OCT) based on protocol-defined thresholds (mean baseline central subfield thickness 412 μm [provided as a Stratus® [Carl Zeiss Meditec] time domain equivalent throughout the remainder of this report]), and no prior anti-VEGF treatment within 12 months of enrollment. The eyes were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to intravitreous injections of aflibercept (2.0 mg), bevacizumab (1.25 mg), or ranibizumab (0.3 mg). If the non-study eye needed an anti-VEGF injection, the same agent as the study eye was used.

Participants had visits every 4 weeks during the first year and every 4 to 16 weeks during the second year depending on treatment course. At each visit, study eyes were assessed for retreatment with the anti-VEGF agent based on visual acuity and OCT criteria. Starting at the 6-month visit focal/grid laser treatment was administered if DME persisted and was not improving. Medical monitoring of all adverse events was completed by a masked physician at the Coordinating Center. A secondary review by another masked physician independent of the DRCR.net was performed for all serious adverse events to confirm pre-specified safety outcomes.

At annual visits the visual acuity and OCT technicians were masked to treatment group. Investigators and study coordinators were not masked. Participants were masked until the primary results were published in February 2015, when they were informed of the study’s primary results and informed of their treatment group assignment. At that time, if deemed warranted by the investigator, the study participant could switch anti-VEGF agents after discussion with the Protocol Chair.

The 2-year analyses methods mirrored the 1-year analyses.2 The primary analysis consisted of three pairwise comparisons of mean visual acuity change from baseline in the 3 treatment groups using an analysis of covariance model, adjusted for baseline visual acuity, with the Hochberg method used to control overall type I error.6 The primary analysis followed the intention-to-treat principle, including all randomized eyes. Central subfield thickness was analyzed similarly, with additional adjustment for baseline thickness. For visual acuity, multiple imputation was used to impute missing 2-year data and outlying values were truncated to 3 standard deviations from the mean.7 Binary visual acuity and central subfield thickness outcomes were analyzed using binomial regression or Poisson regression with robust variance estimation.8 Observed data are presented for summary statistics unless otherwise specified. For adverse events and number of treatments, global P-values for the overall 3-group comparison were calculated; pairwise comparisons were calculated if the global P-value was <0.05, adjusting for multiple treatment comparisons.9 All P-values are 2-sided. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Results

The 2-year visit was completed by 90%, 85%, and 88% of the 660 randomized participants (91%, 90%, and 91% excluding deaths), in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively (Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). There were no substantial differences identified in the baseline characteristics of those who completed and those who did not complete the 2-year visit (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). For those who completed 2 years, the median number of visits during the second year was 10 in all three groups (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Among participants completing the 2-year visit, the median (interquartile range) numbers of intravitreous injections during the 2 years were 15 (11-17), 16 (12-20), and 15 (11-19) injections in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively (global P=0.08), with 5 (2-7), 6 (2-9), and 6 (2-9) injections, respectively, between the 1 and 2 year visits (global P=0.32, Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Most eyes (84%) received at least 1 injection in the second year, and 98% of the protocol-required injections (based on visual acuity and OCT) were given over the 2 years (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The percentages of eyes receiving at least 1 session of focal/grid laser during the 2 years were 41%, 64%, and 52% in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively (global P<0.001; pairwise comparisons: P<0.001 for aflibercept-bevacizumab, P=0.04 for aflibercept-ranibizumab, and P=0.01 for ranibizumab-bevacizumab), with 20%, 31%, and 27%, respectively, receiving at least 1 session of focal/grid laser in the second year (global P=0.046, Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Three eyes in the aflibercept group, 10 in the bevacizumab group, and 1 in the ranibizumab group received 1 or more alternative treatments for DME other than the randomly assigned anti-VEGF or focal/grid laser. Only one of the eyes receiving alternative treatment occurred after the participant had been unmasked to their treatment assignment and informed of the 1-year results (one eye in the bevacizumab group received aflibercept).

Effect of Treatment on Visual Acuity

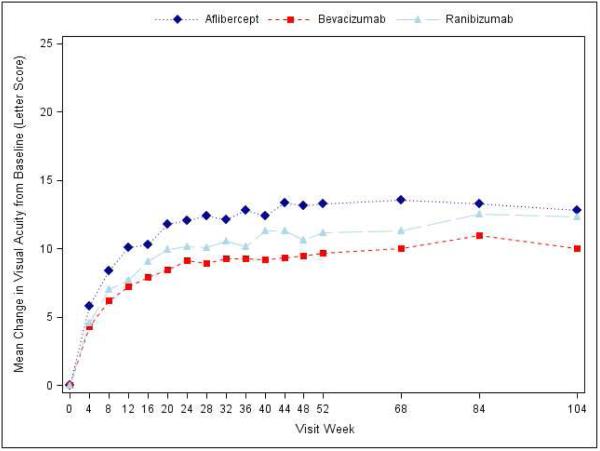

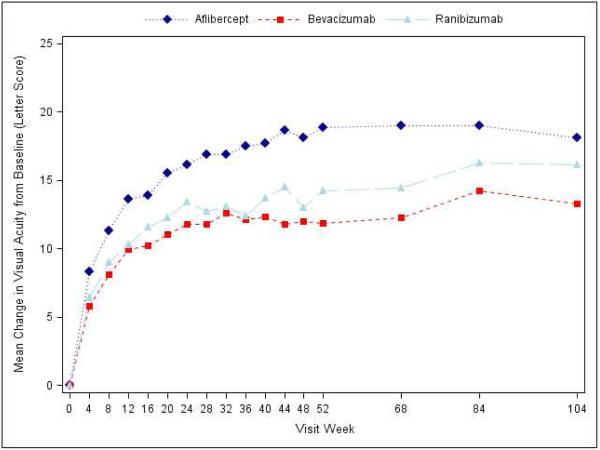

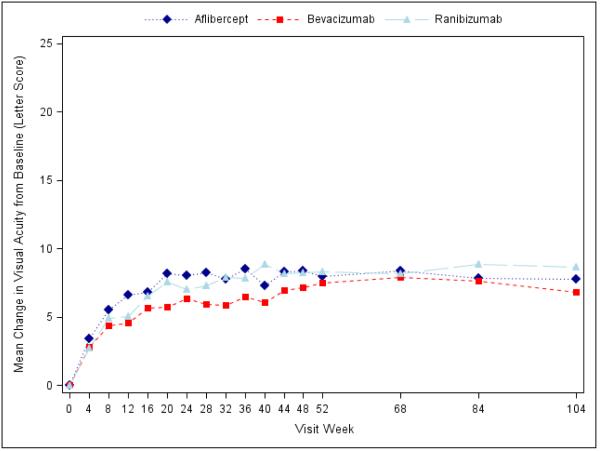

Visual acuity at the 2-year visit improved from baseline, on average, by 12.8 letters with aflibercept, 10.0 letters with bevacizumab, and 12.3 letters with ranibizumab (pairwise comparisons: P=0.02 for aflibercept-bevacizumab, P=0.47 for aflibercept-ranibizumab, and P=0.11 for ranibizumab-bevacizumab; Supplementary Appendix Table S3, Figure 1, Supplementary Appendix Figure S3). However, the relative effect of the treatments varied by initial visual acuity (P value for interaction=0.02 with baseline visual acuity letter score as a continuous variable, and P value for interaction=0.11 with baseline visual acuity as a binary variable [letter score (69 or better or worse than 69 [approximate Snellen equivalent 20/50])]; Table 1 and Supplementary Appendix Figure S2). Specifically, when initial visual acuity letter score was <69 (“20/50 or worse” , approximately 50% of the cohort), mean visual acuity letter score improvement from baseline to the 2-year visit was +18.1 ±13.8, +13.3 ± 13.4 and +16.1 ± 12.1 respectively (95% confidence intervals [CI] and P-values for differences in mean change for aflibercept-bevacizumab: +4.7 (+0.5 to +8.8) [P=0.02], aflibercept-ranibizumab: +2.3 (−1.1 to +5.6) [P=0.18], and ranibizumab-bevacizumab: +2.4 (−1.0 to +5.8) [P=0.18]; Table 1). When initial visual acuity letter score was 78 to 69 (“20/32 or 20/40”), mean letter score improvement at the 2-year visit was +7.8 ± 8.4 for aflibercept, +6.8 ± 8.8 for bevacizumab, and +8.6 ± 7.0 for ranibizumab without any statistically significant differences between groups (Table 1). Sensitivity analyses with different approaches for handling missing data and outlier values produced similar results (Supplementary Appendix Table S4).

Figure 1.

Mean Change in Visual Acuity over Time, A) Overall; B) and C) Stratified by baseline visual acuity (approximate Snellen equivalent): 20/50 or worse (B) and 20/32-20/40 (C). Change in visual acuity was truncated to 3 standard deviations from the mean. The number of eyes at each time point ranged from 195-224 in the aflibercept group, 185-218 in the bevacizumab group, and 188-218 in the ranibizumab group (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix and Figure S2 in the 1 Year Supplementary Appendix2 for the number at each time point).

Table 1.

Visual Acuity at 2 Years Stratified by Visual Acuity Subgroup

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Visual Acuity 20/50 or Worse (Letter Score <69) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Observed Data | Treatment Group Comparisons Differences in Mean Change or Difference in Proportions Adjusted 95% CI and Adjusted P Value |

|||||

| Aflibercept (N=98) |

Bevacizumab (N=92) |

Ranibizumab (N=94) |

Aflibercept vs Bevacizumab |

Aflibercept vs Ranibizumab |

Ranibizumab vs Bevacizumab |

|

| Baseline | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 55.8 ± 11.1 | 56.9 ± 10.5 | 56.1 ± 10.1 | |||

| ~Snellen equivalent | 20/80 | 20/80 | 20/80 | |||

| 1 Year (in 2 yr cohort) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 75.4 ± 10.4 | 69.6 ± 12.0 | 70.8 ± 12.0 | |||

| ~ Snellen equivalent | 20/32 | 20/40 | 20/40 | |||

| Mean Change ±SD | 19.4 ± 11.1 | 12.6 ± 11.8 | 14.7 ± 10.2 | |||

| 2 Year | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 74.3 ± 13.3 | 69.8 ± 15.7 | 71.9 ± 14.6 | |||

| ~Snellen equivalent | 20/32 | 20/40 | 20/40 | |||

| Change from baseline (letter score) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | +18.1 ±13.8 | +13.3 ± 13.4 | +16.1 ± 12.1 | +4.7 (+0.5 to +8.8) P=0.020 |

+2.3 (−1.1 to +5.6) P=0.18 |

+2.4 (−1.0 to +5.8) P=0.18 |

| ≥ 10 letter improvement |

74 (76%) | 61 (66%) | 67 (71%) | +10% (−6% to +26%) P=0.35 |

+3% (−9% to +15%) P=0.57 |

+7% (−6% to +20%) P=0.57 |

| ≥ 10 letters worsening |

5 (5%) | 8 (9%) | 2 (2%) | −3% (−10% to +3%) P=0.49 |

+2% (−3% to +7%) P=0.49 |

−5% (−13% to +3%) P=0.33 |

| ≥ 15 letter improvement |

57 (58%) | 48 (52%) | 52 (55%) | +8% (−9% to +25%) P=0.74 |

+2% (−11% to +15%) P=0.75 |

+6% (−8% to +20%) P=0.75 |

| ≥ 15 letters worsening |

2 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | −2% (−7% to +3%) P=0.86 |

0% (−4% to +4%) P=0.86 |

−2% (−6% to +3%) P=0.86 |

|

| ||||||

| Baseline Visual Acuity 20/32-20/40 (Letter Score 78- 69) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Observed Data |

Treatment Group Comparisons

Differences in Mean Change or Difference in Proportions Adjusted 95% CI and Adjusted P Value |

|||||

|

Aflibercept

(N=103) |

Bevacizumab

(N=93) |

Ranibizumab

(N=97) |

Aflibercept vs

Bevacizumab |

Aflibercept vs

Ranibizumab |

Ranibizumab vs

Bevacizumab |

|

| Baseline | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 73.5 ± 2.6 | 73.0 ± 2.9 | 73.4 ± 2.7 | |||

| ~Snellen equivalent | 20/32 | 20/40 | 20/40 | |||

| 1 Year (in 2 yr cohort) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 81.3 ± 8.3 | 79.8 ± 10.5 | 81.8 ± 6.8 | |||

| ~ Snellen equivalent | 20/25 | 20/25 | 20/25 | |||

| Mean Change± SD | 7.9 ± 7.7 | 7.3 ±7.3 | 8.4 ± 6.8 | |||

| 2 Year | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 81.2 ± 8.3 | 79.3 ± 11.4 | 82.0± 6.8 | |||

| ~Snellen equivalent | 20/25 | 20/25 | 20/25 | |||

| Change from baseline (letter score) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | +7.8 ± 8.4 | +6.8 ± 8.8 | +8.6 ± 7.0 | +1.1 (−1.1 to +3.4) P=0.51 |

−0.7 (−2.9 to +1.5) P=0.51 |

+1.9 (−0.9 to +4.7) P=0.31 |

| ≥ 10 letter improvement |

51 (50%) | 38 (41%) | 45 (46%) | +9% (−7% to +25%) P=0.52 |

+4% (−10% to +17%) P=0.59 |

+5% (−8% to +19%) P=0.59 |

| ≥ 10 letters worsening |

4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (−6% to +5%) P=0.96 |

+3% (−3% to +8%) P=0.55 |

−3% (−8% to +3%) P=0.55 |

| ≥ 15 letter improvement |

21 (20%) | 16 (17%) | 18 (19%) | +1% (−10% to +11%) P=0.89 |

+2% (−8% to +11%) P=0.89 |

−1% (−11% to +10%) P=0.89 |

| ≥ 15 letters worsening |

3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | +1% (−3% to +5%) P=0.69 |

+2% (−2% to +5%) P=0.69 |

−1% (−4% to +3%) P=0.69 |

CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation, See Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix for detailed footnote

Percentages of eyes with at least 10 or at least 15 letter changes at the 2-year visit are provided in Table 1 and Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix and Figure S4 in the Supplementary Appendix; there were no statistically significant differences between groups for any of the binary visual acuity outcomes, overall or within visual acuity subgroups. The detailed distribution of visual acuity at 2 years is provided in Supplementary Appendix Table S5. There was no statistically significant interaction between treatment and any of the 3 other pre-planned baseline factors: OCT central subfield thickness, prior anti-VEGF treatment, or lens status (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). Mean change in visual acuity over two years stratified in a post-hoc analysis by both baseline visual acuity and central subfield thickness is provided in Figure S5 in the Supplementary Appendix; within the better baseline vision eyes with thicker baseline central subfield thickness (400 microns or thicker on time domain equivalent), there was a suggestion of less VA improvement in the bevacizumab group than the other two groups.

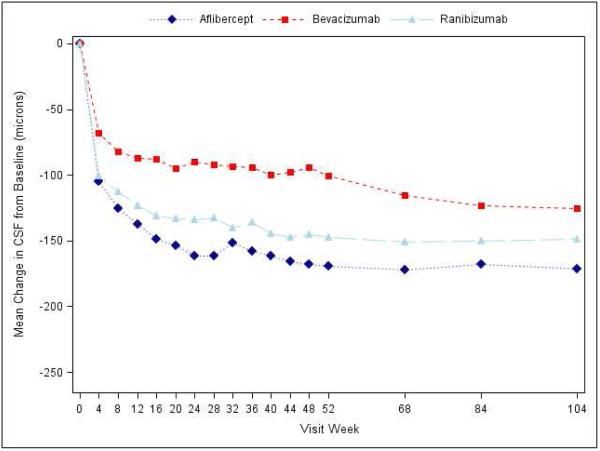

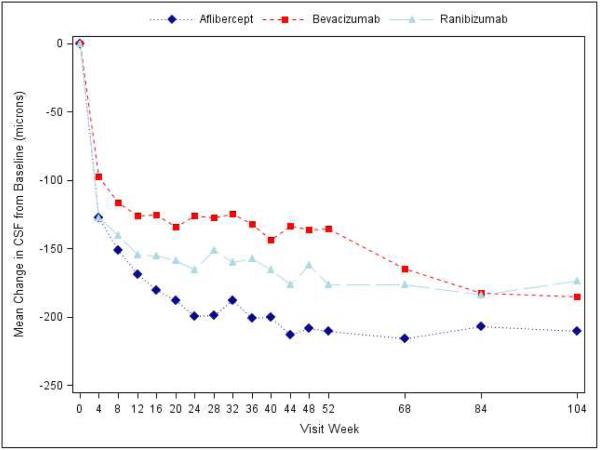

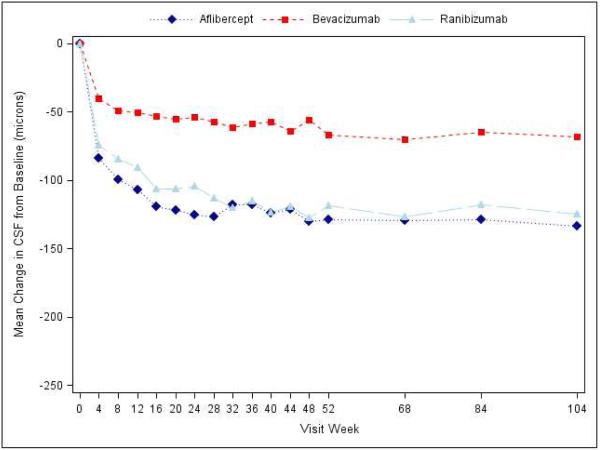

Effect of Treatment on Macular Edema

At the 2-year visit, central subfield thickness decreased on average by 171±141 microns with aflibercept, 126±143 microns with bevacizumab, and 149±141 microns with ranibizumab (95% confidence intervals and P-values for differences in mean change for aflibercept-bevacizumab: −48.5 [−70.0 to −27.0 (P<0.001)], aflibercept-ranibizumab: −15.5 [−33.0 to +2.0 (P=0.08)], and ranibizumab-bevacizumab: −33.0 [−53.4 to −12.6 (P<0.001)]; Supplementary Appendix Table S7). The number of eyes achieving central subfield thickness <250μm (based on Zeiss Stratus equivalent) was 141 (71%), 75 (41%) and 121 (65%) eyes, respectively. The relative treatment effect on central subfield thickness varied based on initial visual acuity (P value for interaction <0.001, Table 2; Figure 2). When initial visual acuity was “20/50 or worse,” central subfield thickness at 2 years decreased on average by 211±155, 185±158, and 174±159 microns with aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab, respectively; eyes with initial visual acuity “20/32 or 20/40” decreased 133±115, 68±98, and 125±118 microns, respectively. Change in retinal volume from baseline to 2 years is reported in Supplementary Appendix Table S8.

Table 2.

OCT Central Subfield Thickness at 2 Years Stratified by Visual Acuity Subgroup

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Visual Acuity 20/50 or Worse (Letter Score <69) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Observed Data | Treatment Group Comparisons Differences in Mean Change or Difference in Proportions Adjusted 95% CI and Adjusted P Value |

|||||

| Aflibercept (N=97) |

Bevacizumab (N=89) |

Ranibizumab (N=91) |

Aflibercept vs Bevacizumab |

Aflibercept vs Ranibizumab |

Ranibizumab vs Bevacizumab |

|

| Baseline CSF | 450 ± 142 | 471 ± 153 | 430 ± 135 | |||

| Mean ± SD | ||||||

| 1 year (in 2 year cohort) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 236 ± 74 | 325 ± 150 | 249 ± 95 | |||

| Mean chg ± SD | −212±152 | −143±155 | −177±149 | |||

| 2 year | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 236 ± 82 | 282 ± 108 | 253 ± 115 | |||

| Mean chg ± SD | −211 ± 155 | −185 ± 158 | −174 ± 159 | −42.1 (−77.2, −7.0) P=0.013 |

−19.3 (−47.8, +9.3) P=0.19 |

−22.8 (−52.2, +6.6) P=0.19 |

| CSF <250 μm | 73 (75%) | 41 (46%) | 60 (66%) | +31% (+14%, +47%) P<0.001 |

+12% (−1%, +25%) P=0.076 |

+19% (+2%, +35%) P=0.021 |

|

| ||||||

| Baseline Visual Acuity 20/32-20/40 (Letter Score 78- 69) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

|

Aflibercept

(N=101) |

Bevacizumab

(N=93) |

Ranibizumab

(N=95) |

Aflibercept vs

Bevacizumab |

Aflibercept vs

Ranibizumab |

Ranibizumab vs

Bevacizumab |

|

| Baseline CSF | 373 ± 108 | 360 ± 82 | 377 ± 97 | |||

| Mean ± SD | ||||||

| 1 year (in 2 year cohort) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 243±57 | 296±83 | 259±83 | |||

| Mean change ± SD | −127±111 | −62±61 | −117±111 | |||

| 2 year | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 237 ± 50 | 291 ± 95 | 250 ± 81 | |||

| Mean change ± SD | −133 ± 115 | −68 ± 98 | −125 ± 118 | −57.3 (−82.7, −31.9) P<0.001 |

−11.8 (−32.4, +8.8) P=0.26 |

−45.4 (−69.6,−21.3) P<0.001 |

| CSF <250 μm | 68 (67%) | 34 (37%) | 61 (64%) | +33% (+17%, +49%) P<0.001 |

+2% (−12%, +15%) P=0.81 |

+32% (+16%, +47%) P<0.001 |

CSF = central subfield, OCT = Optical coherence tomography, CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation See Table S7 in the Supplementary Appendix for detailed footnote

Figure 2.

Mean Improvement in Optical Coherence Tomography Central Subfield Thickness over Time, A) Overall; B) and C) Stratified by baseline visual acuity (approximate Snellen equivalent): 20/50 or worse (B) and 20/32-20/40 (C). The number of eyes at each time point ranged from 192-221 in the aflibercept group, 181-216 in the bevacizumab group, and 185-215 in the ranibizumab group (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix and Figure S2 in the 1 Year Supplementary Appendix2 for the number at each time point).

Safety

Ocular adverse events over two years are summarized in Table 3 and Tables S13-S14 in the Supplementary Appendix. One injection-related infectious endophthalmitis occurred in each group.

Table 3.

Pre-Specified Adverse Events of Interest Occurring During 2 Years

| Aflibercept (N=224) |

Bevacizumab (N=218) |

Ranibizumab (N=218) |

P – value** |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Eye Ocular Adverse Events | ||||

|

No. of study eye injections

Pre-specified ocular events occurring at least once (No. Eyes) |

2998 | 3115 | 3066‡ | |

| Endophthalmitis | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0.66 |

| Inflammation | 6 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 0.69 |

| Retinal detachment (traction, rhegmatogenous , or unspecified) |

2 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1.0 |

| Retinal tear | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1.0 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 15 (7%) | 17 (8%) | 10 (5%) | 0.37 |

| Injection Related Cataract | 3 (1%) | 2 (<1%) | 0 | 0.38 |

| Intraocular pressure elevation* | 39 (17%) | 27 (12%) | 35 (16%) | 0.31 |

|

| ||||

| Non-Study Eye Ocular Adverse Events (Eyes Receiving Study Treatment) | ||||

|

| ||||

| No. of non-study eyes treated | N=144 | N =134 | N =132 | |

| No. of injections | 1180 | 1316 | 1225‡‡ | |

|

Pre-specified ocular events occurring at least once from

the first injection (No. Eyes) |

||||

| Endophthalmitis | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0.77 |

| Inflammation | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (2%) | 0.79 |

| Retinal detachment(traction, rhegmatogenous , or unspecified) |

0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Retinal tear | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0.10 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 11 (8%) | 12 (9%) | 9 (7%) | 0.83 |

| Injection Related Cataract | 2 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0.78 |

| Intraocular pressure elevation* | 18 (13%) | 15 (11%) | 18 (14%) | 0.85 |

|

| ||||

| Systemic Adverse Events | ||||

|

| ||||

|

Vascular Events According to Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration [14]

occurring at least once (No. Participants) |

||||

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction | 7 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 6 (3%) | |

| Non-fatal stroke | 2 (<1%) | 6 (3%) | 11 (5%) | |

| Vascular death (from any potential vascular or unknown cause) |

3 (1%) | 8 (4%) | 9 (4%) | |

| Any Antiplatelet Trialists` Collaboration Event | 12 (5%) | 17 (8%) | 26 (12%) | 0.047*** |

|

Pre-specified systemic events occurring at least once

(No. Participants) |

||||

| Death (any cause) | 5 (2%) | 13 (6%) | 11 (5%) | 0.12 |

| Hospitalization | 77 (34%) | 71 (33%) | 73 (33%) | 0.93 |

| Serious adverse event | 88 (39%) | 81 (37%) | 82 (38%) | 0.90 |

| Gastrointestinal †† | 67 (30%) | 64 (29%) | 60 (28%) | 0.85 |

| Kidney§§ | 50 (22%) | 46 (21%) | 35 (16%) | 0.22 |

| Hypertension | 39 (17%) | 27 (12%) | 44 (20%) | 0.080 |

Seven study eyes received 1 injection and 2 eyes received 2 injections of 0.5 mg of ranibizumab prior to the FDA approving a 0.3mg dosage of ranibizumab for DME treatment.

Non-study eyes receiving 0.5 mg dose of ranibizumab: 8 received 1 injection, 2 received 2 injections, 1 received 4 injections, 1 received 5 injections, 1 received 9 injections, 1 received 11 injections.

Includes intraocular pressure increase ≥10mmHg from baseline at any visit, intraocular pressure ≥30 mmHg at any visit, initiation of intraocular pressure-lowering medications not in use at baseline, or glaucoma surgery.

Global (overall 3 group comparison) P-value from Fisher’s Exact Test.

Includes events with a Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class of gastrointestinal disorders

Includes a subset of Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class of renal and urinary disorders events indicative of intrinsic kidney disease, plus increased/abnormal blood creatinine or renal transplant from other system organ classes

Pairwise comparisons from Fisher’s Exact Test (adjusted for multiple comparisons by taking the maximum of the global and pairwise comparison P-values): aflibercept-bevacizumab: P=0.34, aflibercept-ranibizumab: P=0.047, bevacizumab-ranibizumab: P=0.20.

Global P-value from Poisson model with robust variance estimation using the log link,8 adjusting for gender, age at baseline, Hemoglobin A1c at baseline, diabetes type, diabetes duration at baseline, insulin use, prior coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, prior transient ischemic attack, prior hypertension, smoking status: P=0.089.

Systemic adverse events over two years are provided in Table 3 and Tables S9-S12 and S15 in the Supplementary Appendix. Across the 3 treatment groups, the numbers of serious adverse events reported (37%-39%) and of participants hospitalized (33%-34%) within two years were similar (global P=0.90 and 0.93, respectively). In the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively, there were 2%, 6%, and 5% deaths (global P=0.12) and 5%, 8%, and 12% in pre-specified analysis using the Anti-platelet Trialists Collaboration definition of events (global P=0.047; pairwise comparisons: P=0.34 for aflibercept-bevacizumab, P=0.047 for aflibercept-ranibizumab, and P=0.20 for ranibizumab-bevacizumab; global P adjusted for twelve potential baseline confounders [listed in a footnote to Table 3] =0.09, global P adjusted for prior myocardial infarction or prior stroke=0.06). The higher rate of APTC events for ranibizumab included more non-fatal strokes (2 for aflibercept, 6 for bevacizumab, 11 for ranibizumab) and vascular deaths (3 for aflibercept, 8 for bevacizumab and 9 for ranibizumab). In a post-hoc analysis among the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab participants, respectively, without a history of stroke or myocardial infarction prior to study entry 5% (10/203), 6% (12/193), and 9% (17/193) developed an APTC event, while with a history of a prior stroke or myocardial infarction 10% (2/21), 20% (5/25), and 36% (9/25) developed an APTC event (Supplementary Appendix Table S10).

In a post-hoc analysis, among treatment group comparisons in 24 MedDRA system organ classes, one treatment group difference was associated with a P-value less than 0.05 (ear and labyrinth disorders), presumably a chance finding due to the large number of comparisons (Supplementary Appendix Table S11). When combining the systems of cardiac and vascular disorders, 31%, 32%, and 38% (global P=0.26) of participants had at least one event in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups respectively (Supplementary Appendix Table S12).

Discussion

This randomized trial of eyes with vision-impairing center-involved DME compared treatment with intravitreous aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab. Focal/grid laser was added per protocol after 6 months when DME persisted and was no longer improving. All three regimens, on average, produced substantial visual acuity improvement through 2 years. However, as in year 1, the relative treatment effect differed by baseline visual acuity. At 2 years, in eyes with better baseline visual acuity, there still were no meaningful differences identified in mean visual acuity change among the treatment groups. In eyes with baseline VA of 20/50 or worse, the advantage of aflibercept over ranibizumab, noted at 1 year, had decreased and was no longer statistically significant at 2 years, while aflibercept remained superior to bevacizumab. Few eyes in any group lost substantial amounts of vision, regardless of the baseline visual acuity.

In eyes with baseline visual acuity of 20/50 or worse, the visual acuity differences between aflibercept and the other two agents were clinically relevant at 1 year; the relative difference in percentage of eyes in the aflibercept group that gained 15 or more letters at one year was 63% greater than in the bevacizumab group (67% vs. 41%) and 34% greater than in the ranibizumab group (67% vs. 50%).2 However, at 2 years these relative differences were only 12% (58% vs. 52%) and 5% (58% vs. 55%), respectively. Similar small relative differences were seen for a 10 or more letter improvement at two years (15% and 7% respectively), raising the question of whether differences observed at 2 years are clinically relevant.

At year 1, bevacizumab was less effective at reducing retinal thickness than the other 2 agents. This difference persisted in year 2 among the eyes with better initial visual acuity. If this finding was coupled with visual acuity benefits it could be judged relevant, however, as a difference in acuity was not identified with better initial visual acuity, this observation may not be of clinical importance.

Over 2 years, the cumulative numbers of injections were similar across the 3 treatment arms, with the number in year 2 being about half that in year 1. Through 2 years, laser treatment was required less frequently in aflibercept-treated eyes than with the other 2 agents. Since laser was a protocol-defined part of the treatment regimen, it is not possible to separate the effect of macular laser from the anti-VEGF treatment on the VA and thickness outcomes.

Rates of ocular adverse events, including endophthalmitis and post-injection inflammation, remained low through 2 years with all 3 agents. Systemic APTC rates were higher in the ranibizumab group, with a greater number of non-fatal strokes and vascular deaths in the ranibizumab group. Although the P-values increased slightly after adjusting for a history of prior stroke or myocardial infarction and other potential confounders, this did not substantially alter the results. These findings have not been demonstrated consistently in previously reported clinical trials. Supplemental Table S16 and Figure S6 summarize 2-year APTC events from prior anti-VEGF studies for DME and choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). In the Rise and Ride trials of eyes with DME, a higher percentage of participants in the pooled 0.5 mg ranibizumab group (7.2%) had an APTC event than in the 0.3 mg ranibizumab group (5.6%) or the control group (5.2%).5 In Rise, 0.3 mg ranibizumab had the lowest rate of participants with an APTC event among the 3 treatment groups and in Ride it had the highest. In DRCR.net Protocol I, fewer participants experienced an APTC event during 2 years in the 0.5 mg ranibizumab group (7%) than in the laser group (13%).3 In previous trials of AMD, 2 year percentages of participants with an APTC event were similar between ranibizumab and bevacizumab groups and between aflibercept and ranibizumab groups.10, 11, 12 Across multiple retinal diseases, a meta-analysis from Thulliez et al did not identify an increased risk of major cardiovascular or hemorrhagic events with ranibizumab compared with control.13 It is noteworthy that the 12% frequency of ranibizumab managed participants with one or more APTC events in the current study appears to be larger relative to the other trials, including DRCR.net protocol I where the percentage was 7% with high overlap in DRCR.net clinical centers. The inconsistencies in the totality of the evidence create uncertainty as to whether there is a true increased risk of APTC events with ranibizumab at this time.

Strengths of the study include excellent compliance with the standardized retreatment regimen (98%), making it unlikely that a potential limitation of bias to treat or not to treat on the part of the unmasked ophthalmologist influenced the outcomes. Furthermore, good retention among the living participants, with approximately 90% of all enrolled eyes across all 3 groups completing the 2-year visit, makes it unlikely that losses to follow-up biased the results. Another potential limitation is that participants were unmasked to treatment group after the 1-year results were published; however, only one study participant switched to an alternative anti-VEGF treatment after the unmasking. Since the eligibility criteria were relatively broad with participants enrolled among 89 community- and university-based sites across the U.S., the results likely are generalizable to similarly characterized patients treated in a similar manner. The absence of other similarly designed comparative effectiveness trials across these three anti-VEGF agents precludes comparing these results to other studies.

In summary, this DRCR.net comparative effectiveness study for center involved DME showed vision gains in all three drugs at the 2-year visit, with an average of almost half the number of injections, slightly decreased frequency of visits, and decreased amounts of focal/grid laser treatment in all 3 groups in the second year. Among eyes with better VA at baseline no difference was identified in vision outcomes through the 2-year visit. For the eyes with worse VA at baseline, the advantage of aflibercept over bevacizumab for mean VA gain persisted through 2 years, although the difference at 2-years was diminished. The VA difference between aflibercept and ranibizumab for eyes with worse VA at baseline that was noted at 1 year had decreased at 2 years. The implications of the increased rate of APTC events with ranibizumab found in the current study is uncertain due to inconsistency with prior trials. The results from this randomized clinical trial provide strong evidence for ophthalmologists to consider when applying this information to individual patients with DME.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported through a cooperative agreement from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services EY14231, EY14229, EY18817.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organization (National Institutes of Health) participated in oversight of the conduct of the study and review of the manuscript but not directly in the conduct of the study, nor in the collection, management, or analysis of the data. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

2-year randomized trial for center-involved DME; all groups had vision improvements; similar vision among groups when vision started 20/32-20/40; superior vision for aflibercept over bevacizumab, but not ranibizumab, when 20/50-20/320; more APTC events with ranibizumab.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A published list of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network investigators and staff participating in this protocol can be found in: Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N, Wells JA, Glassman AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-203. A current list of DRCR.net investigators is available at www.drcr.net.

Financial Disclosures: A complete list of all DRCR.net investigator financial disclosures can be found at www.drcr.net.

Additional Contributions: Regeneron Pharmaceutical provided the aflibercept and Genentech provided the ranibizumab for the study. Genentech also provided funding for an ancillary study that is not part of the main study reported herein. As per the DRCR.net Industry Collaboration Guidelines (available at www.drcr.net), the DRCR.net had complete control over the design of the protocol, ownership of the data, and all editorial content of presentations and publications related to the protocol.

References

- 1.Jampol LM, Glassman AR, Bressler NM. Comparative Effectiveness Trial for Diabetic Macular Edema: Three Comparisons for the Price of 1 Study From the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(9):983–4. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N. Wells JA, Glassman AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1064–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do DV, et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Edema: 100-Week Results From the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, et al. Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema: Results from 2 Phase III Randomized Trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochberg Y. A sharper bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schafer J. Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;8:3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westfall PH, Wolfinger, Russell D. Closed Multiple Testing Procedures and PROC MULTITEST. http://support.sas.com/kb/22/addl/fusion22950_1_multtest.pdf

- 10.Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeration Trials (CATT) Research Group. Martin DF, Maguire MG, et al. Ranibizumab and Bevacizumab for Treatment of Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration: Two-Year Results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kaiser PK, Korobelnik JF, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninety-six-week results of the VIEW studies. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thulliez M, Angoulvant D, Le Lez ML, et al. Cardiovascular events and bleeding risk associated with intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibodies: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(11):1317–26. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy--I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients BMJ. 1994;308(6921):81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.