Abstract

Despite consistent high rates of campus sexual assault, little research has examined effective strategies to decrease sexual assault victimization. Sexual assault and drinking protective behavioral strategies (PBS) may be important means of reducing sexual assault victimization risk on college campuses but need further examination. The current study examined the relationship among sexual assault in childhood, before college, and since college to evaluate the mitigating roles of both sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS on sexual assault victimization. Participants (n = 620) were undergraduate women, 18 to 20 years old. The current study was a cross-sectional online survey assessing participants’ sexual assault PBS and sexual assault history. Sexual assault history was positively associated with future sexual assault experiences. Pre-college sexual assault was associated with increased since-college sexual assault and increased drinks per week. Since-college adolescent/adult sexual assault was associated with less use of sexual assault PBS. These findings suggest that PBS may have an important role in sexual assault victimization and future research should examine their usefulness in risk reduction programs for college women.

Keywords: sexual assault, alcohol use, college women, protective behavioral strategies

Sexual assault is a prevalent and costly problem for college students. Within the last two decades, the U.S. government has mandated college campuses that receive federal funding to provide sexual assault prevention education (National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, 1994). Despite these efforts, rates have not significantly declined over time (Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007): National surveillance studies report approximately 20% of women will experience a sexual assault during college (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher, & Martin, 2009). Campus sexual assault has gained greater priority and visibility with the creation of the White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault (The White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault, 2014). Although the Task Force has provided best practice recommendations to colleges (The White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault, 2014), it has acknowledged the limited empirical base for sexual assault perpetration reduction programs (DeGue, 2014). In addition to sexual assault perpetration prevention programming, colleges should also provide sexual assault victimization risk reduction programming to students. By targeting perpetration, prevention programming directly targets the responsible party. Although effective perpetration prevention strategies targeting college students are still in development (DeGue et al., 2014), a potential victim may potentially reduce her risk of being assaulted by engaging in protective behaviors. These protective behaviors will not ultimately prevent an assault from occurring; instead they may reduce one’s risk of being targeted for perpetration. The current study is an investigation into the use of specific protective behavioral strategies (PBS) related to sexual assault victimization and revictimization in college.

The rates of sexual revictimization—multiple experiences of sexual assault—are a particular problem among college women (Black et al., 2011). Sexual revictimization may occur within different time frames across development, from CSA (childhood sexual abuse) to ASA (adolescent/adult sexual assault) or within the same time frame (multiple ASA experiences). Cumulative experiences of sexual trauma are associated with negative mental health outcomes (Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Zinzow et al., 2011), and impairment in physical health, interpersonal relationships, and occupational and academic pursuits (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005; Jordan, Combs, & Smith, 2014). The mechanisms underlying revictimization are complex and not well understood. One potential contributor is that several coping strategies for managing the mental health symptoms associated with sexual assault include increased sexual activity or increased drinking (Testa, Hoffman, & Livingston, 2010). Such coping strategies may in the short term relieve mental health symptoms but put an individual at risk for revictimization as perpetrators may target these women (Parks, Hequembourg, & Dearing, 2008).

Many women enter college with a sexual assault history and are at risk for revictimization (for review, see Roodman & Clum, 2001), thus sexual assault PBS should be explored as a potential intervention tactic. Women who are drinking are targeted for sexual assault by perpetrators with alcohol involvement in approximately 50% to 75% of sexual assaults (Reed, Amaro, Matsumoto, & Kaysen, 2009), and preliminary evidence suggests that the use of drinking PBS is associated with lower rates of sexual assault victimization (Gilmore, Stappenbeck, Lewis, Granato, & Kaysen, 2015; Palmer, McMahon, Rounsaville, & Ball, 2010). A combined examination of sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS and their association with sexual assault victimization and revictimization is warranted.

Sexual Assault PBS

Some researchers have identified certain protective strategies as potential tools for reducing the risk of being targeted for a sexual assault (e.g., Moore & Waterman, 1999). Sexual assault PBS include, but are not exclusive to, letting a friend or family member know where one is meeting a date and/or acquaintance and carrying money for transportation if the woman wishes to leave the date. Sexual assault PBS focus on reducing the likelihood that a perpetrator would target a woman for sexual assault by increasing the woman’s protective behaviors. This is inherently challenging, as the perpetrator is ultimately responsible for sexual assault. However, certain situational and behavioral factors are associated with increased likelihood for being targeted for sexual assault victimization; for example, a victim’s nonverbal behavior may indicate vulnerability to a perpetrator (Parks, Hequembourg, & Dearing, 2008; Sakaguchi & Hasegawa, 2006). Such perpetrators may include not only social acquaintances and/or casual partners but also romantic partners (e.g., boyfriends) who may perpetrate sexual assault when their partner is vulnerable (Logan, Walker, & Cole, 2015). Sexual assault PBS were developed to address several of these factors without blaming women if they are sexually assaulted or asking them to forego dating/social situations.

Previous research indicates that sexual assault PBS may have an important, yet generally unstudied, relationship with sexual assault. Cross-sectional investigations prevent the identification of PBS as a mechanism of sexual assault and yield inconsistent findings. In one study, a sexual assault history was negatively associated with the use of PBS such that individuals with a sexual assault history were less likely to report using PBS than those without a history (Breitenbecher, 2008). Other studies have found no relationship between sexual assault PBS and sexual assault victimization (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1997; Moore & Waterman, 1999). However, these studies only measured a sexual assault history as forced or incapacitated oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse. They did not investigate unwanted sexual contact, sexual coercion as a tactic to obtain unwanted sex, or experiences of CSA, thus limiting the range of women’s sexual trauma histories. These studies also utilized dichotomous response options, thus limiting the ability to differentiate between women with repeated experiences of victimization.

The use of sexual assault PBS may be particularly relevant to women with pre-existing sexual assault or child sexual abuse histories. Women with sexual assault histories report less self-efficacy following an assault, as well as freezing responses that may interfere with their ability to utilize sexual assault PBS (Edwards et al., 2014; Orchowski, Gidycz, & Raffle, 2008). It should be noted that it is not the implication that women are responsible for preventing their own sexual assault. As victims are never responsible for their assault and that the fault always lies with the perpetrator, it is possible that women may use sexual assault PBS and still be assaulted. In fact, women with a sexual assault history may have learned that the use of any PBS (e.g., drinking PBS), not just sexual assault PBS, did not prevent them from being assaulted. Therefore, additional PBS warrant inclusion when assessing protective factors in sexual assault, specifically those related to alcohol use.

Drinking PBS

Women who drink are disproportionally targeted by sexual assault perpetrators. Women are more likely to experience sexual assault on days of heavy episodic drinking (Parks, Hsieh, Bradizza, & Romosz, 2008) compared with non-drinking days. Intoxicated women may be targeted for many reasons, including decreased risk perception and decreased likelihood of using effective resistance strategies. Alcohol administration experiments suggest that women perceive sexual assault risk less and resist sexual advances less effectively while intoxicated compared with when they are sober (Norris et al., 2006; Testa, Livingston, & Collins, 2000).

Drinking PBS are associated with less high-risk alcohol use (e.g., Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Lewis, Rees, Logan, Kaysen, & Kilmer, 2010; Pearson, 2013; Prince, Carey, & Maisto, 2013). Drinking PBS include strategies such as eating before drinking, avoiding drinking games, and alternating alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. The use of these skills is associated with less risk of alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Lewis et al., 2010; Pearson, 2013). Sexual assault is a particularly problematic negative consequence of alcohol use, indicating that it is possible for the use of drinking PBS to serve as a protective factor against sexual assault. An exception to these findings is the event-level examination of within-person drinking behaviors (e.g., use of PBS during specific instances of drinking; for review, see Pearson, 2013). Previous research has found that on days that individuals used certain drinking PBS, participants consumed more alcohol than usual (Lewis et al., 2011; Pearson, D’Lima, & Kelley, 2013). Because we are examining global drinking PBS rather than event-level PBS, the relationship between sexual assault and drinking PBS is expected to be consistent with the research on global drinking PBS and negative consequences.

The relationship between drinking PBS and sexual assault is relatively new to the field. To our knowledge, only two studies have examined the relationship between drinking PBS and sexual victimization. The first study found an initial association between sexual assault victimization and drinking PBS with sexual assault victimization in the past year being associated with less use of drinking PBS (Palmer et al., 2010). A further examination found that college women with a history of alcohol-involved sexual assault were less likely to use drinking PBS compared with those without such histories (Gilmore et al., 2015). It was also found that any history of sexual assault (CSA, verbally coerced sexual assault, alcohol-involved sexual assault, and physically forced sexual assault) was associated with less use of serious harm reduction drinking PBS (Gilmore et al., 2015). However, the role of drinking PBS in sexual revictimization has not yet been examined. Furthermore, the frequency and severity of sexual assault victimization was not taken into account in these two previous studies. Given the dearth of research in the area and because of the strong relationship between drinking PBS and alcohol-related negative consequences, it is essential to further examine the relationship between drinking PBS and sexual assault in college women.

Because alcohol plays a central role in the sexual assault of college women, it is necessary to examine if both sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS are protective against experiencing sexual assault and revictimization during college. The current study is a cross-sectional examination of the relationship between sexual assault (CSA, pre-college ASA, and since-college ASA), drinking PBS, and sexual assault PBS among college women.

Hypotheses

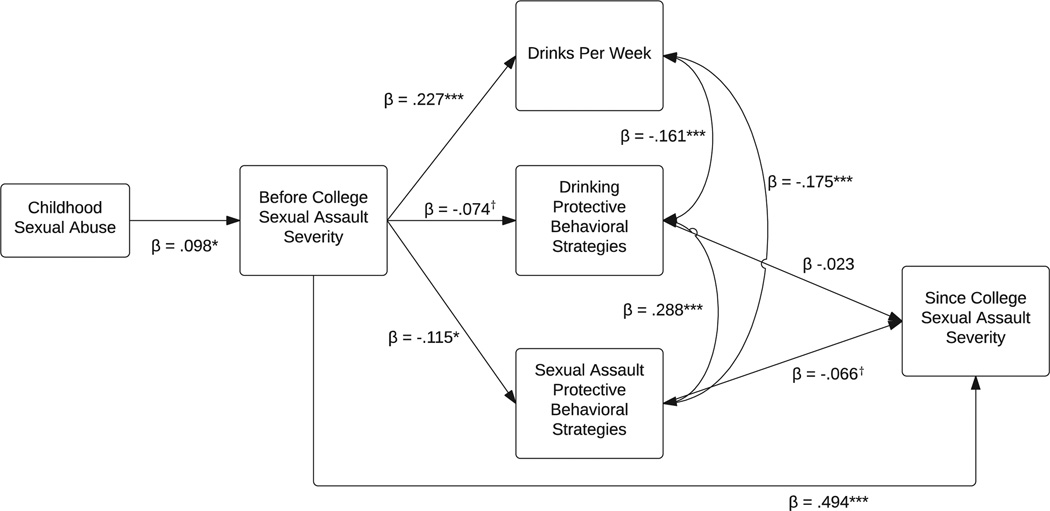

Consistent with previous findings (Black et al., 2011; Messman-Moore & Long, 2003), it is hypothesized that previous sexual assault will be associated with later sexual assault victimization. It is also hypothesized that sexual assault severity will be associated with less use of sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that more use of sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS will be associated with less ASA since college (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model with standardized coefficients.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Method

Participants

Participants included college women (n = 620) aged 18 to 20 (M = 18.78; SD = 0.85). The majority (61.5%) were in college for less than a year, were not in a sorority (78.4%), spoke English as a first language (64.0%), and lived on campus (65.1%). The majority were Asian American/Pacific Islander (42.7%) or White (40.2%) and 9.8% were multiracial, 2.8% were Black/African American, 2.5% identified as “Other,” 0.7% were American Indian/Alaska Native, and 3.4% chose to not identify their race. In addition, 8.1% of participants identified as Hispanic/Latina. Participants drank on average 3.85 (SD = 6.47) drinks per week and one third of the participants (33.3%) reported having never engaged in consensual sex.

Measures

Sexual assault PBS

Participants answered a revised version of the Dating Self-Protection against Rape Scale (15 items, α = .94; Breitenbecher, 2008; Moore & Waterman, 1999) to assess sexual assault PBS. Questions asked how often (5-point Likert-type scale; 1 = never and 5 = always) participants performed a number of behaviors to protect themselves from possible sexual assault when on a date. Questions included “meet in a public place instead of a private place” and “tell a friend who you are meeting and where.” Rather than simply ask about behaviors occurring on a date, the questionnaire was revised to include behaviors when with “someone who is sexually interested in you.” Mean composite scores were computed by averaging each participant’s responses (α = .93).

Drinking PBS

Participants were asked 15 items from the PBS (Martens et al., 2005), with answer choices ranging on a 5-point scale (1 = always and 5 = never). Items were reverse scored for analyses. Participants were asked while using alcohol or “partying” whether they utilized a variety of behaviors (e.g., “determine not to exceed a set number of drinks,” “avoid mixing different types of alcohol,” and “know where your drink had been at all times”). The items were averaged for a total drinking PBS score (α = .94).

Childhood sexual abuse

CSA was assessed via a revised two-item version of the CSA questionnaire (Finkelhor, 1979). This scale asked about childhood sexual experiences prior to the age of 14, perpetrated by an individual who was 5 years or older than the participant and by someone of similar age. Participants were asked whether “anyone who was at least 5 years older than you touched or fondled your body in a sexual way or made you touch or fondle their body in a sexual way.” Participants were then asked whether such experience ever occurred with “anyone close to your age.” Participants were categorized as having a CSA history (yes = 1) or no history (no = 0).

Sexual assault incidence and severity

The Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss et al., 2007) assessed participants’ coerced sexual experiences at two time points: after their 14th birthday but prior to entering college, and since entering college. As not all women label coercive behavioral experiences as sexual assault or rape, behaviorally specific questions yield more reliable data about experiences of sexual trauma (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000). Sexual assault experiences included unwanted sexual touching or contact, attempted (oral, anal, or vaginal) penetration, and completed penetration. Questions assessed the tactic through which sexual assault was attempted or completed: verbal coercion, incapacitation, threats of physical force, and physical force. Participants indicated the number of times that a tactic or multiple tactics were used up to 3 times (0 = never to 3 = 3 or more times). Sexual assault incidence and severity was determined using a 63-point scale (Davis et al., 2014). The scoring procedure used frequency and severity of experiences by multiplying each experience (0, 1, 2, or 3) by the victimization experience (1 = sexual contact by verbal coercion, 2 = sexual contact by incapacitation, 3 = sexual contact by force, 4 = attempted or completed rape by verbal coercion, 5 = attempted or completed rape by incapacitation, 6 = attempted or completed rape by force) and summing the total number of experiences with the highest possible score being 63 and the lowest possible score of 0 (no sexual assault history). For example, an individual with two experiences of attempted or completed rape by incapacitation (5 severity level) and one instance of sexual contact by force (3 severity level) would receive a score of 13 ([2 × 5] + [1 × 3]).

Drinks per week

The average number of drinks consumed per week was used as a covariate in the model. Participants completed the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985), which asks about the average number of drinks for each day of a typical drinking week. The items were totaled for a drinks per week score.

Procedure

College undergraduate students from introductory psychology courses were recruited through the university’s psychology department website where students in psychology courses can find available studies. The study was described as an online study about “drinking and sexual behaviors.” Eligible participants completed the online survey. Following completion of the survey, participants were provided with information and resources for sexual assault and substance use. Data collection for the current manuscript was part of a larger study examining the effectiveness of a sexual assault risk reduction program (Gilmore, Lewis, & George, 2015). Only individuals who completed the full assessment baseline survey were included in the current manuscript. Participants were given extra course credit for their participation.

Results

Descriptives

Bivariate correlations revealed significant negative correlations between sexual assault history and both PBS (see Table 1). One hundred forty-three participants (23%) reported having either a pre- or since-college sexual assault (28.2% and 21.6% of sample, respectively), and 83 participants (13%) reported having both. On average, participants reported a pre-college ASA severity score of 3.82 (SD = 9.27) and a since-college severity score of 1.86 (SD = 5.87).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlations.

| Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any History | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. CSA history | 78 (12.6%) | — | 1.00 | |||||

| 2. Pre-college ASA | 175 (28.2%) | 3.87 (9.25) | .14** | 1.00 | ||||

| 3. Since-college ASA | 134 (21.6%) | 2.03 (5.87) | .084* | .50** | 1.00 | |||

| 4. Drinking PBS | — | 3.71 (0.92) | −.08 | −.16** | −.18** | 1.00 | ||

| 5. Sexual assault PBS | — | 2.85 (1.17) | −.12** | −.14** | −.17** | .34** | 1.00 | |

| 6. Drinks per week | 3.85 (6.47) | .022 | .24** | .34** | −.30** | −.24** | 1.00 | |

Note. CSA = childhood sexual abuse; ASA = adolescent/adult sexual assault; PBS = protective behavioral strategies.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Data Analysis Plan

The hypothesized model (see Figure 1) was tested in Mplus 7 using a path model with maximum-likelihood estimation. To assess model fit, chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were used. Good model fit was indicated with a nonsignificant chi-square, RMSEA values < .06, CFI values > .90, and SRMR values < .06 (Kline, 2005). Because the data were cross-sectional in nature, an alternate model was tested with drinking and sexual assault PBS as outcomes of CSA, before-college ASA, and since-college ASA (see Figure 2). In both models, drinks per week was used as a covariate. A comparison of the models was conducted using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A model with a BIC that is 6 to 10 smaller than another model indicates strong evidence that the model is a better fit (Kass & Raftery, 1995). A model with smaller AIC than another indicates evidence of a better fitting model (Kline, 2005).

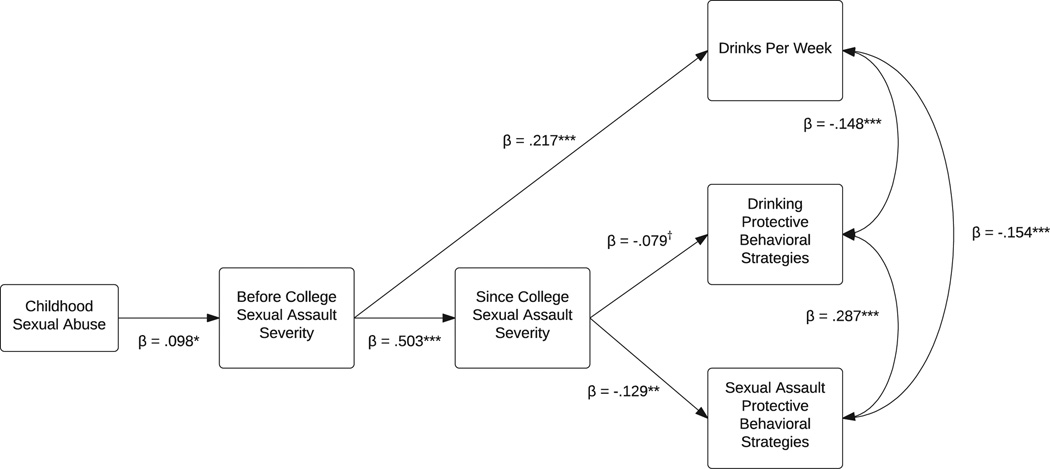

Figure 2.

Alternative (final) model with standardized coefficients.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Model Testing

The hypotheses were tested in a path model (see Figure 1) that was a not good fit for the data, χ2(3) = 44.54, p < .01, RMSEA = .117, CFI = .88, SRMR = .044. CSA history was associated with more severe pre-college ASA (β = .098, p < .05). Pre-college ASA severity was associated with lower use of sexual assault PBS (β = −.115, p < .01) and there was a trend toward significance with lower use of drinking PBS (β = −.074, p = .075). Pre-college ASA severity was associated with higher drinks per week (β = .227, p < .001). There was a trend toward significance where the use of more sexual assault PBS (β = −.066, p = .08) was associated with less severe ASA since college. Within this model, drinking PBS was not associated with since-college ASA (β = −.023, p > .05). More severe ASA experiences before college were associated with more severe since-college ASA (β = .494, p < .001). The use of drinking PBS and sexual assault PBS were positively associated with each other (β = .288, p < .001).

The second model tested drinking and sexual assault PBS as outcomes of CSA, before-college ASA, and since-college ASA (see Figure 2). This alternate model was a good fit for the data, χ2(5) = 7.42, p = .28, RMSEA = .02, CFI = .99, SRMR = .02. CSA history was associated with more severe precollege ASA (β = .098, p < .05). More severe ASA experiences before college were associated with more severe ASA experiences since college (β = .503, p < .001). More severe ASA experiences before college were associated with greater drinks per typical week (β = .217, p < 0.001). More severe ASA since college was associated with less use of sexual assault PBS (β = −.129, p < .01) and marginally associated with less use of drinking PBS (β = −.079, p = .057). Finally, the use of drinking PBS and sexual assault PBS were positively associated with each other (β = .287, p < .001). Examination of the structural model showed that small to moderate amount of variance was accounted for since-college ASA (R2 = .25), sexual assault PBS (R2 = .02), drinking PBS (R2 = .01), before-college ASA (R2 = .01), and drinks per week (R2 = .05).

To further compare our models, we utilized the BIC and AIC. The BIC is utilized to compare nested models based on the likelihood function and prevents overfitting by penalizing models with more parameters. A model that has a BIC that is 6 to 10 smaller than another model indicates strong evidence that the model is a better fit (Kass & Raftery, 1995). The BIC suggested that the alternative model was a better fit for the data than the original hypothesized model (BIChypothesized = 15,502.62; BICalternate = 15,459.14; BICdifference = 115.48). Similar to the BIC, AIC was also utilized and confirmed selection of the alternative model over the hypothesized model (AIChypothesized = 15,414.46; AICalternate = 15,376.34; AICdifference = 38.12).

Discussion

This study expanded on previous research by examining the relationships between child and adolescent sexual assault, drinking PBS, sexual assault PBS, and college sexual victimization. This extends previous research which examines sexual assault history and drinking PBS or sexual assault history and sexual assault PBS separately. As hypothesized, CSA was associated with ASA before college, and ASA before college was associated with higher incidence and severity of ASA since entering college. In contrast to our hypotheses, we rejected our hypothesized model in favor of our alternative model in which drinking and sexual assault PBS are outcomes of since-college sexual assault, rather than mediators. There was a marginally significant relationship between since-college ASA and less use of drinking PBS. Although this effect does not meet statistical significance, the model fit well when this path was modeled and prior research supports this finding (Gilmore et al., 2015). Although we cannot infer directionality or causality, PBS appear to be an important component in the prevention of sexual assault and revictimization and further study is needed. Future research should assess if teaching both sexual assault and drinking PBS is effective for college sexual assault risk reduction programs.

Consistent with prior findings, a history of sexual assault was associated with increased risk for experiencing subsequent sexual assault (Classen et al., 2005; Messman-Moore & Long, 2003). Although experiences of sexual violence are associated with less use of drinking PBS (Gilmore et al., 2015), this study contributes to this literature by demonstrating an association between sexual victimization and the use of both drinking and sexual assault PBS. It is possible that multiple experiences of sexual violence compound to reduce the likelihood of using PBS, which may be a risk factor for future revictimization. Although it is surprising that sexual assault survivors engage in PBS at lower rates than women without such histories, these findings have valuable implications for understanding risk factors of revictimization and informing clinical intervention to prevent future assault. It is possible that women with histories of sexual assault experience decreased self-efficacy to use PBS, especially if they engaged in sexual assault and drinking PBS and were nonetheless victimized. Future research should take this possibility into consideration given that women may be unaware of these PBS and the reason why one chooses to not engage in these behaviors may be associated with their victimization histories. However, as previously stressed, the responsibility of the assault remains solely with the perpetrator.

Survivors of sexual trauma may have additional psychological barriers to utilizing PBS relative to women without histories of sexual trauma. Psychological barriers, such as perceptions of negative socio-emotional consequences of PBS (e.g., embarrassment, negative feedback from peers), are associated with increased victimization (Gidycz, Rich, Orchowski, King, & Miller, 2006; Orchowski, Untied, & Gidycz, 2012). Women with histories of sexual assault may perceive additional or more severe socio-emotional consequences to their use, thus potentially decreasing the likelihood of using a drinking or sexual assault PBS. Women with a sexual assault history also report decreases in self-efficacy following an assault (Orchowski et al., 2008). One’s general sense of self-efficacy could influence the use of PBS because they may not believe they can effectively implement strategies even if they did want to use them. Although not directly examined here, survivors of child trauma are noted to respond more passively to lower levels of stress than women without such histories (Norris et al., 2006), thus survivors of sexual trauma may be less able to engage in PBS in response to a potentially risky or dating situation. It is possible that in a social or dating situation, survivors of sexual assault may experience an underlying fear response—possibly related to past trauma—that results in a freeze response and as a result, inhibits their ability to engage in PBS (Edwards et al., 2014). Future research should examine barriers to utilizing PBS among women with a sexual assault history as well as investigate the relation between drinking and sexual assault PBS and survivors’ in-the-moment affective responses to social and/or dating situations. Although these findings point to a number of potential barriers, they point to a number of prevention opportunities, especially with the lack of empirically driven sexual assault perpetration prevention programs (DeGue et al., 2014).

Although future research is needed, the finding that less utilization of sexual assault and drinking PBS are outcomes of sexual revictimization is compelling. If women with sexual assault histories arrive at college and experience sexual assault, it may be possible to intervene directly and teach drinking and sexual assault PBS to sexual assault survivors. Expanding discussion of psychological barriers to target the needs of sexual assault survivors while teaching behavior-specific skills may be a comprehensive way of increasing protective factors against sexual assault. Notably, the relationship between since-college ASA and sexual assault PBS was stronger than drinking PBS. It may be feasible for interventions targeting sexual assault PBS to include alcohol-related strategies, rather than treating them as exclusive. Given that survivors of sexual assault may be susceptible to low self-efficacy and shame (Classen et al., 2005), it is vital that the responsibility of assault is placed on the perpetrator and victim blaming does not occur.

Effective sexual assault risk reduction programs require an understanding of the role of alcohol use in sexual assault. Before-college sexual assault was associated with greater number of drinks per week. Although the results within this sample were marginally significant, women with sexual assault histories utilize drinking PBS less than women without such histories (Gilmore et al., 2015). Decreased alcohol consumption is one way to decrease one’s risk of sexual assault (Testa & Livingston, 2009). Similar to findings that women with sexual assault histories are less likely to use sexual assault PBS, these women are also less likely to use drinking PBS. It is possible that PBS have an indirect relationship with sexual assault risk; women who engage in drinking PBS may consume less alcohol that is then associated with decreased risk of sexual assault. Future research should explore this relationship as the temporal precedence within this study prevented examining these indirect effects. Similar to what was described above, women with sexual assault histories may be consuming more alcohol as a coping strategy, which further increases their risk (for review, Messman-Moore & Long, 2003). Future research should include sexual assault and drinking PBS as a hypothesized mechanism, and investigate sexual assault and drinking PBS in formal preventive sexual assault intervention.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the current findings are compelling, additional research in the relations between drinking PBS, sexual assault PBS, and sexual assault victimization is necessary to inform sexual assault risk reduction programs. The current study only assesses drinking and sexual assault PBS that college women are already engaging in; it does not assess the utility of teaching PBS to college women. Despite the focus on naturally occurring PBS, this study is the first to investigate the relation between sexual assault experiences and both sexual assault and drinking PBS.

More research assessing drinking PBS and sexual assault PBS as mechanisms of sexual revictimization is also necessary. The current research is cross-sectional, and causal mechanisms cannot be ascertained. While we did not find drinking and sexual assault PBS mediated victimization experiences, this may be due in part to the temporal precedence; ASA since entering college could have occurred at any point in the past year to 3 years, and PBS were evaluated at a global level. A longitudinal investigation into how PBS change over time may identify such a relationship. This study also did not directly examine the role of alcohol and sexual risk-taking. Women with CSA and/or ASA histories may engage in sexual and alcohol risk-taking to cope with negative affect (Littleton, Grills, & Drum, 2014; Testa et al., 2010). These coping responses might interfere with women’s ability to utilize drinking and sexual assault PBS, and future research should consider examining these in the context of PBS use. The participants of the study also limit the generalizability of these findings. The participants were undergraduate women ages 18 to 20; while college women were recruited because they have a high risk of experiencing sexual assault, the results should be interpreted with caution as to whether they can be applied to non-college populations. Furthermore, the sample was from one university, and the demographics of the population may not be generalizable to other college communities. When investigating and evaluating PBS as a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or a component of a larger intervention, measures of social desirability should be included. It is possible that victims who disclose sexual assault in a study at one time point may be more likely to disclose sexual assault at another time point, thus the revictimization findings could reflect that possibility. Although prior research indicates that the use of web-based surveys reduces the risk of social desirability in reporting alcohol risk behaviors (Crutzen & Goritz, 2010), social desirability has been associated with lower reports of sexual victimization (Yarkovsky & Timmons, 2014). Future research should also include metrics of social desirability to control for potential underreporting in sexual activity and drinking. Furthermore, the measurement and computation of ASA severity does not allow for actual frequency of sexual assault to be calculated because the number of each experience is capped at three. If women have more than three experiences of a type of sexually assaultive experience, this ASA severity scoring may not fully capture their range of their experiences. However, this ASA severity scoring is an improvement over previous systems in that it incorporates the severity of tactic, type of sexual act, and frequency (Davis et al., 2014).

Although sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS are modeled as distinct constructs, there is considerable overlap between the two. The high correlation between the constructs is likely due to the generally adaptive safety behaviors included within these two constructs. However, there are meaningful differences between the behaviors within the constructs and the behaviors they target. Ultimately, drinking PBS target drinking behaviors whereas sexual assault PBS target sexual assault risk awareness and response strategies. Given the consistent findings that alcohol consumption and sexual assault are intertwined, future research may integrate drinking and sexual assault PBS into a new set of protective strategies that target alcohol-involved sexual assault. Finally, the sexual assault PBS measure may not accurately reflect the sexual assault PBS that are applicable to today’s college women. New measures that accurately reflect the sexual assault PBS that are typically used in today’s college women are needed. Future research should also examine the role of psychological barriers and the intent to utilize these strategies on their implementation (Orchowski et al., 2012).

Implications

Future research is needed to replicate these findings with longitudinal methodologies and perhaps RCTs. One could not infer causality from longitudinal designs either, but they could provide additional insight into a temporal sequence of use of PBS. Perhaps the use of drinking and sexual assault PBS alter for women over time and they could either change concomitantly or discrepantly. Future research could further examine these relationships and other potential factors that could contribute to use of PBS.

RCTs could also examine if teaching sexual assault and drinking PBS would be useful to college women. Although the current research does suggest a relationship between PBS and sexual revictimization, it is unclear whether teaching PBS will yield a protective factor against future sexual assault. If found to be an effective protective factor, both sexual assault and drinking PBS should be incorporated into sexual assault risk reduction programs that have demonstrated efficacy (for review, see Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Vladutiu, Martin, & Macy, 2011). Additional research should also evaluate the sustainability of such prevention interventions and determine factors that support sustained use of PBS. Future research should also examine the relations between these constructs in women who are not attending college, as well as low-income women whose rates of sexual assault remain less clear.

These findings cannot be reserved for potential victims of sexual assault but should be replicated in sexual assault perpetration prevention. For example, the use of drinking PBS could also reduce a man’s likelihood of perpetrating sexual assault. Future research should examine the association between drinking PBS and sexual assault perpetration among college students.

Conclusion

A sexual assault experience is highly predictive of subsequent sexual assault incidence and severity, and the mechanisms and outcomes of revictimization are complex. Empirically supported programs that target sexual assault revictimization are needed. Although researchers and administrators may be aware of this need, empirical research into behaviorally specific points of intervention has been limited. Use of sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS was associated with multiple experiences of sexual violence. Given the public health necessity to prevent sexual assault, risk reduction programming could include teaching sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS to incoming college students as a potentially powerful and empirically sound intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Data collection and manuscript preparation was supported by grants from the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31AA020134, PI: A.K. Gilmore), the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington, and the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington.

Biographies

Elizabeth C. Neilson, MSW, MPH, is currently a clinical psychology doctoral student at the University of Washington in Seattle. Her research interests are in the field of coercive and traumatic sexual experiences, with a primary interest in mechanisms of sexual assault perpetration. She is interested in interventions targeting the intersection of sexual aggression, sexual risk-taking, and substance use. Another primary interest concerns race, ethnicity, and cultural factors as they relate to sexual risk-taking and substance use. She received her BA in psychology and women’s studies from the University of Michigan in 2006 where her research focused on the role of sex education in contraceptive use, sexual risk-taking, and sexual assertiveness. She then obtained a dual master’s degree in social work and public health from the University of Michigan where she researched the impact of both child sexual abuse and adult sexual assault on pregnancy, post-partum, and early parenting experiences. Following this program, she worked as a clinical social worker in Chicago where she provided evaluations and individual and group psychotherapy to low-income children, parents, and families who had experienced trauma. Her clinical interests focus on providing empirically supported treatments to marginalized communities with limited access to therapeutic services. She is specifically interested in the treatment of trauma, concurrent treatment of substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and treatment of eating disorders.

Amanda K. Gilmore, PhD, studies the etiology and reduction/prevention of sexual assault and sexual health problems as it relates to substance use. Her research interests include (a) the relationship between substance use and sexual assault; (b) sexual risk behaviors and sexual functioning as potential mediators and outcomes of the relationship between substance use and assault, respectively; and (c) the role of individual differences in influencing these associations. She was awarded an NIAAA and intramural grant, which funded her dissertation of a randomized controlled trial testing a web-based sexual assault risk and alcohol use reduction program for heavy drinking underage college women. She completed her clinical internship at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division. Her clinical interests focus on the treatment of substance use, trauma symptoms, and suicidal behavior. Her clinical orientation focuses on empirically driven behavioral, cognitive-behavioral, and third-wave therapies to treat mood, anxiety, substance use, and personality disorders.

Hanna T. Pinsky is an undergraduate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she is pursuing a dual degree in psychology and public health. She has worked as a research assistant on a randomized control trial investigating a sexual assault risk and alcohol use reduction intervention, as well as a member of a social psychology lab investigating implicit stereotypes and prejudices. She has worked with veteran and prison populations.

Molly E. Shepard graduated from Seattle University with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice in 2012 and will be attending Palo Alto University in fall 2015 to pursue a doctorate degree in clinical psychology. Her research interests are grounded in the intersection of psychology and criminology as they relate to sexual and physical aggression. She has served on the Domestic Violence support team through the Victim Support Team of the Seattle Police Department. She has worked as a research assistant on a randomized control trial examining sexual assault risk and alcohol use reduction at University of Washington under Amanda Gilmore, and works as a full-time legal secretary at an insurance defense firm in downtown Seattle.

Melissa A. Lewis, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington. She received her doctorate in health and social psychology from North Dakota State University in 2005 and completed her postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Washington’s Center for the Study of Health and Risk Behaviors in 2007. She has been a member of the faculty at the University of Washington since 2007. Her substantive research interests lie in examining social-psychological principles in broadly defined health-related behaviors. She studies social and motivational mechanisms involved in etiology and prevention of addictive and high-risk behaviors (e.g., drinking, risky sexual behavior, hooking up). She has particular expertise in personalized feedback interventions aimed at reducing drinking and related risky sexual behavior. She also explores who might be more prone to take part in high-risk health behaviors, such as those who are more sensitive to social pressures. A fundamental assumption of her research is that because social pressures and influences have been consistently and strongly implicated in risky health behaviors, especially among young adults, interventions aiming to reduce susceptibility to these influences hold particular promise. She has previously been awarded the Addictive Behaviors Special Interest Group Early Career Award of the Association for Behavior and Cognitive Therapies and has received grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, and the Alcohol Beverage Medical Research Foundation.

William H. George, PhD, is a full professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington where he has been a faculty member since 1992. He received his doctoral degree from the University of Washington and completed his postdoctoral fellowship at the Addictive Behaviors Research Center in the University of Washington’s Department of Psychology. His current research focuses on the influence of alcohol on sexual health behavior and related constructs. Grounded in alcohol expectancy theory and alcohol myopia theory, he conducts surveys and laboratory-based experiments examining the potentially disinhibiting effects of alcohol on sexual perception, sexual arousal, sexual aggression, and HIV/AIDS-related sexual risk-taking. He is also interested in racism, ethnicity, and cultural factors broadly. A particular focus is how cultural factors and racial stereotypes interact with the above topics. His secondary areas of interest include theories and therapies pertaining to addictions—especially Relapse Prevention applications, sex offenders, and the adult sexuality of survivors of child sexual abuse. He has received the Davida Teller Distinguished Faculty Award twice and has received grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute for Mental Health, and the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson LA, Whiston SC. Sexual assault education programs: A meta-analytic examination of their effectiveness. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:374–388. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbecher K. The convergent validities of two measures of dating behaviors related to risk for sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1095–1107. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen R, Goritz AS. Social desirability and self-reported health risk behaviors in web-based research: Three longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Gilmore AK, Stappenbeck CA, Balsan MJ, George WH, Norris J. How to score the sexual experiences survey? A comparison of nine methods. Psychology of Violence. 2014;4:445–461. doi: 10.1037/a0037494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S. Prevention sexual violence on college campuses: Lessons from research and practice. 2014 (Report prepared for the White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault). Retrieved from https://www.notalone.gov/schools/

- DeGue S, Valle LA, Holt MK, Massetti GM, Matjasko JL, Tharp AT. A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19:346–362. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Probst DR, Tansill EC, Dixon KJ, Bennett S, Gidycz CA. In their own words: A content-analytic study of college women’s resistance to sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29:2527–2547. doi: 10.1177/0886260513520470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. What’s wrong with sex between adults and children? Ethics and the problem of sexual abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1979;49:692–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1979.tb02654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice and Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Rich CL, Orchowski L, King C, Miller AK. The evaluation of a sexual assault self-defense and risk reduction program for college women: A prospective study. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Lewis MA, George WH. A randomized controlled trial targeting alcohol use and sexual assault risk among college women at high risk for victimization. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.007. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Stappenbeck CA, Lewis MA, Granato HF, Kaysen D. Sexual assault history and its association with the use of drinking protective behavioral strategies among college women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:459–464. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, Muehlenhard CL. College women’s fears and precautionary behaviors relating to acquaintance rape and stranger rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:527–547. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan CE, Combs JL, Smith GT. An exploration of sexual victimization and academic performance among college women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15:191–200. doi: 10.1177/1524838014520637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling: Methodology in the social sciences. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. College women’s experiences with physically forced, alcohol- or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health. 2009;57:639–647. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Patrick ME, Lee CM, Kaysen DL, Mittman A, Neighbors C. Use of protective behavioral strategies and their association to 21st birthday alcohol consumption and related negative consequences: A between-and within-person evaluation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;26:179–186. doi: 10.1037/a0023797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rees M, Logan DE, Kaysen DL, Kilmer JR. Use of drinking protective behavioral strategies in association to sex-related alcohol negative consequences: The mediating role of alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:229–238. doi: 10.1037/a0018361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Grills AE, Drum KB. Predicting risky sexual behavior in emerging adulthood: Examination of a moderated mediation model among child sexual abuse and adult sexual assault victims. Violence and Victims. 2014;29:981–998. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Walker R, Cole J. Silenced suffering: The need for a better understanding of partner sexual violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2015;16:111–135. doi: 10.1177/1524838013517560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:537–571. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Waterman CK. Predicting self-protection against sexual assault in dating relationships among heterosexual men and women, gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Journal of College Student Development. 1999;40:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Student Personnel Administrators. Complying with federal regulations: “The Student Right to Know and Security Act”. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, George WH, Stoner SA, Masters N, Zawacki T, Davis K. Women’s responses to sexual aggression: The effects of childhood trauma, alcohol, and prior relationship. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:402–411. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski LM, Gidycz CA, Raffle H. Evaluation of a sexual assault risk reduction and self-defense program: A prospective analysis of a revised protocol. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:204–218. [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski LM, Untied AS, Gidycz CA. Reducing risk for sexual victimization: An analysis of the perceived socioemotional consequences of self-protective behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27:1743–1761. doi: 10.1177/0886260511430391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, McMahon TJ, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA. Coercive sexual experiences, protective behavioral strategies, alcohol expectancies and consumption among male and female college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1563–1578. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hequembourg AL, Dearing RL. Women’s social behavior when meeting new men: The influence of alcohol and childhood sexual abuse. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:145–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh YP, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR. Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, D’Lima GM, Kelley ML. Daily use of protective behavioral strategies and alcohol-related outcomes among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:826–831. doi: 10.1037/a0032516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince MA, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Protective behavioral strategies for reducing alcohol involvement: A review of the methodological issues. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2343–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed E, Amaro H, Matsumoto A, Kaysen D. The relation between interpersonal violence and substance use among a sample of university students: Examination of the role of victim and perpetrator substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:316–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman AA, Clum GA. Revictimization rates and method variance: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:183–204. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi K, Hasegawa T. Person perception through gait information and target choice for sexual advances: Comparison of likely targets in experiments and real life. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2006;30:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA. Alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as mediators of the sexual victimization-revictimization relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:249–259. doi: 10.1037/a0018914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol consumption and women’s vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women’s drinking prevent rape? Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1349–1376. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Collins RL. The role of women’s alcohol consumption in evaluation of vulnerability to sexual aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychology. 2000;8:185–191. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The White House Task Force to Protect Students From Sexual Assault. Rape and sexual assault: A renewed call to action. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.white-house.gov/sites/default/files/docs/sexual_assault_report_1-21-14.pdf.

- Vladutiu CJ, Martin SL, Macy RJ. College- or university-based sexual assault prevention programs: A review of program outcomes, characteristics, and recommendations. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2011;12:67–86. doi: 10.1177/1524838010390708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarkovsky N, Timmons PA. Attachment style, early sexual intercourse, and dating aggression victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29:279–298. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG. Self-rated health in relation to rape and mental health disorders in a national sample of college women. Journal of American College Health. 2011;59:588–594. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.520175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]