Abstract

People are often exposed to more information than they can actually remember. Despite this frequent form of information overload, little is known about how much information people choose to remember. Using a novel “stop” paradigm, the current research examined whether and how people choose to stop receiving new—possibly overwhelming—information with the intent to maximize memory performance. Participants were presented with a long list of items and were rewarded for the number of correctly remembered words in a following free recall test. Critically, participants in a stop condition were provided with the option to stop the presentation of the remaining words at any time during the list, whereas participants in a control condition were presented with all items. Across five experiments, we found that participants tended to stop the presentation of the items to maximize the number of recalled items, but this decision ironically led to decreased memory performance relative to the control group. This pattern was consistent even after controlling for possible confounding factors (e.g., task demands). The results indicated a general, false belief that we can remember a larger number of items if we restrict the quantity of learning materials. These findings suggest people have an incomplete understanding of how we remember excessive amounts of information.

Keywords: memory, metamemory, self-regulated learning, stopping rule, list-length effect

You’ve got to know when to hold ‘em.

Know when to fold ‘em

Know when to walk away

-Kenny Rogers, The Gambler, 1978

How do we know when we have seen enough information, and that we should stop any further input in order to avoid some form of information overload? We are often exposed to large amounts of information, far more than we can actually remember. If we feel we cannot remember it all, when do we stop studying, and what is the basis for this decision? In such situations, we need to make at least two major metacognitive decisions to optimize our memory performance. The first is to prioritize learning materials to selectively encode valuable information that is relevant to our goals. Such selective remembering has been extensively studied in the context of reward-based learning (e.g., Adcock, Thangavel, Whitfield-Gabrieli, Knutson, & Gabrieli, 2006; Ariel, Dunlosky, & Bailey, 2009; Murayama & Kitagami, 2014; but see also Kang & Pashler, 2014), as well as in learning that is guided by the importance or value of the information in question, a process referred to as value-directed remembering (e.g., Castel, 2008; Friedman, McGillivray, Murayama, & Castel, 2015; McGillivray & Castel, 2011). In general, these studies have shown that we are remarkably effective at selectively learning things that are important, a finding that holds even with healthy older adults, who typically exhibit explicit memory deficits (Castel, Murayama, Friedman, McGillivray, & Link, 2013; Spaniol, Schain, & Bowen, 2014).

Complementing this prioritization, a second metacognitive process that guides how much information we decide to remember is evaluating and controlling when to optimally stop encoding information as a method of maximizing learning. Consider a standard memory experiment, where participants are presented with a fixed number of items in a list. Typically, the number of items in each list is far more than what people can actually remember. In these situations, people may feel overwhelmed by the amount of information. Although task instructions emphasize remembering as many items as possible, one strategy may be to make a metacognitive judgment to stop attending to any more items on the list for the remainder of the presentation of the items, with the intent to maximize the number of items remembered. Broadly speaking, as many real-world events are sequential in nature, the examination of whether and how people make strategic decisions to stop sampling novel information is of considerable importance for understanding our cognitive processes in an ecologically-valid manner (see Fiedler, 2000). In fact, this optimal stopping problem has been widely examined in the field of decision making (Browne & Pitts, 2004; Lejuez, Aklin, Zvolensky, & Pedulla, 2003; Seale & Rapoport, 1997).

Despite the large body of literature examining the prioritization aspect of metamemory, there is a decided lack of research that directly addresses this issue of optimal stopping in the context of memory and metamemory research. For example, research regarding self-regulated study (for reviews, see Bjork, Dunlosky, & Kornell, 2013; Son & Kornell, 2008) has investigated decisions to restudy or to not restudy (“drop”) learning materials, and has found that people tend to terminate studying when they feel they have reached some static criterion of mastery (Dunlosky & Thiede, 1998; see also Metcalfe & Kornell, 2005). These studies, however, examine people’s metacognitive decisions to study learning materials more than one time (i.e., multi-trial learning). In other words, this body of research has not directly addressed whether and how people strategically stop studying novel learning materials, especially when they are exposed to seemingly excessive amounts of new information. In a study that looked more specifically at the effects of list length on metamemory, Tauber and Rhodes (2010) examined participants’ judgments of learning (JOLs) when presented with a short list (e.g., 10 words) and a long list (e.g., 100 words). The results showed that participants are insensitive to the possible effects of interference in longer lists, consistently exhibiting overconfidence in their memory performance. Yet, this study speaks little about whether participants are inclined to stop receiving incoming information to maximize their recall performance.

The present study provides the first set of studies that examines metacognitive decisions to stop learning new information. We use a novel experimental paradigm to investigate this process. In this paradigm, participants are presented with a long list of items (i.e., 50 words) one-by-one, and are asked to recall as many items as possible in a following free recall test (monetary incentives are promised for the number of correctly recalled items). Critically, participants are provided with the option to stop the presentation of the remaining words at any time during the list, if they wish. The participant’s goal is to maximize the number of words correctly recalled by stopping or not stopping the presentation of words. We also include a control condition where participants are exposed to all of the words in the list to investigate whether allowing participants to control the presentation of words actually benefits their learning. This new experimental paradigm allows us to examine the novel metacognitive aspect that we discussed so far. Specifically, the current study will examine whether participants opt to stop the presentation of items to maximize the number of items recalled, and whether the metacognitive decision to stop receiving further learning materials actually results in optimal learning performance.

We expect that participants will prefer to stop the presentation of items with the aim to achieve the goal of maximizing the number of recalled words on a later test. There are several possible explanations for this prediction, but one plausible explanation pertains to the limited capacity of our short-term, or working memory (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Shiffrin, 1976). Some memory models indicate that our access to long-term memory is constrained by the limited capacity of our attentional resources (Cowan, 1988). When participants are presented with a long list of items, this limited capacity is likely to cause participants to feel overwhelmed by the amount of information. Such memory overload would create a type of subjective disfluency when processing the encoding of further items, prompting participants to halt or dismiss the incoming information. As the information in working memory would be updated with the presentation of new items, participants may feel that they are forgetting the older items as they are replaced, though this is not actually the case (e.g., Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968). Consequently, participants may become motivated to stop learning new items to prevent “forgetting” old items (see General Discussion for other possible explanations).

Importantly, previous research suggests that people can actually maximize the number of correctly recalled words by not stopping the presentation of words. This prediction comes from the literature on the list-length effect. The list-length effect refers to the phenomenon where the proportion of correctly recalled items from a short list of items is superior to that of a long list. There are a number of empirical studies supporting the list-length effect (Cary & Reder, 2003; Underwood, 1978), but the effect sizes are generally small and there are quite a few studies that yielded null findings (Kinnell & Dennis, 2011). These results suggest that memory accuracy (i.e., the proportion of correctly recalled items) for a list of words is superior for shorter lists, but interestingly, absolute performance at recall seems to be higher for longer lists. In fact, a closer inspection of the literature revealed that the number of items recalled from a list increases as list-length increases (e.g., Ward, 2002). Thus, in the context of the current study, the optimal strategy to maximize the number of recalled items would be to continue to encode as many words as possible.

In summary, the current study tests a hypothesis that people a tendency to stop the presentation of items to maximize the number of recalled words. Additionally, this metacognitive decision should ironically produce suboptimal recall performance due to the aforementioned effects of list-length on gross recall. The current study tests this hypothesis using the new experimental paradigm (stop paradigm) described above.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

A total of 73 undergraduate students (60% female, mean age = 20.6) from the University of California, Los Angeles participated in the study. Participants were randomly assigned to a stop (N = 36) or a control (N = 37) condition. In this and the following experiments (except for Experiment 5), sample size represents the maximum number of participants that could be recruited during the predetermined period of data collection. In addition, all the experiments finished well within the assigned participant time slots; thus, participants were not under time pressure to stop the word presentation.

Materials

One hundred fifty nouns, 4 to 6 letters in length were used as stimuli (e.g., gray, hunter, jazz). The log mean hyperspace analog to language (or HAL, a model of semantics which derives representations for words from analysis of text, Burgess & Lund, 1997) average frequency of the words was 9.26, as obtained from the English Lexicon Project web site (elexicon.wustl.edu; Balota et al., 2007). For each participant, the words were randomly assigned into one of three different lists (50 words for each) in a random order; thus, the assignment of the words to the lists and the word presentation orders were randomized across participants. This type of procedure prevents possible statistical artifacts caused by random item effects (Murayama, Sakaki, Yan, & Smith, 2014). The experiment was created using Collector, a PHP-based open source program for creating experiments online (Garcia & Kornell, 2014).

Procedure

Participants were tested individually in private rooms, seated in front of a computer. Participants were told that they would be presented with three different lists of words, one list at a time, and that each list contained 50 words. They were informed that the goal of the experiment was to recall as many words as possible for each list.

Participants in the control condition were simply presented with 50 words, one at a time, for 2 s each, followed by a 15 s numeric distractor task (“Please count down, out loud, from 495 by 7’s”) and a 60 s free recall task. This cycle was repeated for 3 lists. Participants in the stop condition performed almost the same task, but during the study period there was a checkbox labeled “End list” which they were allowed to click to stop the list early. If participants clicked this box, the currently presented word continued to be displayed for the remainder of the 2 s and the rest of the list was then skipped to proceed directly to the distractor task. It was clarified that it was not mandatory for participants to stop the list presentation; they were instructed that they were free to use this option with whatever strategy they thought would help them recall the largest number of words.

It was possible that participants in the stop condition would be motivated to click the box in order to finish the experiment early. To prevent this possibility and encourage participants to maximize the number of correctly recalled words, we instructed participants that they would be given 10 cents for each word that they correctly recalled during the test. The provision of a monetary incentive also made it clear to participants that the absolute number of items recalled, not the proportion of items recalled, should be maximized.

Results and Discussion

Overall, participants in the stop condition had a tendency to stop the word presentation before the end of the list (Table 1). Specifically, on average, more than half of participants in the stop condition (62%, 95% CI = [46.1%, 77.9%]) halted the presentation of words before the end of the list, and this pattern was consistent across the lists (List 1: 56%; List 2: 64%; List 3: 67%), χ2(2) = 1.02, ns. These results indicate that the majority of participants stopped the presentation of words with the intent to maximize their recall performance. Average serial positions at which they stopped in lists 1–3 (those who did not stop the presentation were counted as 50) were 34.4, 32.1, and 32.3, respectively, and these average positions did not statistically differ across the lists, F (2, 70) = 0.53, η2G = .00.

Table 1.

Participants’ Decision to Stop in the Stop Condition in Experiments 1–5

| Average Rate of Stop

|

Average Position Stopped (out of 50 words)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List 1 | List 2 | List 3 | Overall | List 1 | List 2 | List 3 | Overall | |

| Exp. 1 | 56% | 64% | 67% | 62% | 34.4 (16.7) | 32.1 (16.2) | 32.3 (15.5) | 32.9 (13.6) |

| Exp. 2 | 51% | 51% | 51% | 51% | 34.9 (16.3) | 35.0 (17.6) | 34.0 (17.3) | 34.6 (15.2) |

| Exp. 3 | 41% | 57% | 51% | 50% | 40.2 (14.5) | 35.3 (14.8) | 37.0 (15.0) | 37.5 (12.5) |

| Exp. 4 | 64% | 68% | 68% | 67% | 34.7 (14.4) | 29.6 (16.7) | 26.3 (17.6) | 30.2 (14.6) |

| Exp. 5 (scenario) | - | - | - | 59% | - | - | - | 30.4 (18.0) |

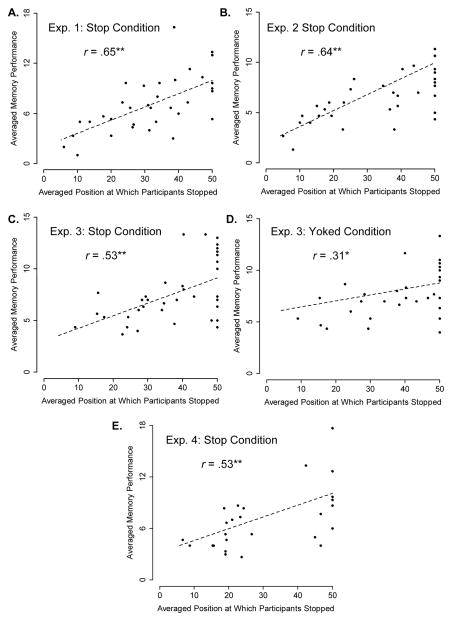

Did the decision to stop the word presentation benefit their memory performance? A 2 (Condition: Stop vs. Control) × 3 (List: 1–3) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) on recall memory performance showed the significant main effect of Condition, F (1, 71) = 4.76, p < .05, η2G = .05. Importantly, the results showed that participants in the stop condition (overall recall performance, M = 7.11, SD = 3.33) remembered significantly fewer words than the participants in the control condition (overall recall performance, M = 8.96, SD = 3.41; see Figure 1). This finding is consistent with the list-length effect (e.g., Ward, 2002), and suggests that, in spite of their intentions to maximize recall performance, stopping the word presentations before the ends of the lists actually undermined memory performance. In fact, when we computed the correlation between the serial position at which participants stopped and their resultant memory performance, the correlation was positive and statistically significant (r = .60 for List 1, .70 for List 2, and .52 for List 3, ps < .01), indicating that participants who stopped earlier showed worse memory performance. Figure 2A plots the relationship between averaged stopped positions and averaged memory performance across all the lists (r = .65, p < .01).

Figure 1.

Number of correctly remembered items as a function of condition (stop vs. control) and lists (lists 1–3) in Experiment 1. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of the averaged position at which participants stopped and their actual recall performance in Experiment 1 (2A), Experiment 2 (2B), the stop condition in Experiment 3 (2C), the yoked condition in Experiment 3 (2D), and the stop condition in Experiment 4.

The main effect of list was also significant, F (2, 142) = 5.87, p < .01, η2G = .02. Post-hoc multiple comparison tests (Shaffer’s method; see Donoghue, 2004) showed that recall performance in List 1 was significantly higher than that in List 2 (p < .01). The interaction between Condition and List was not significant, F (2, 142) = 1.19, η2G = .00, indicating that the recall advantage of the control condition was consistent over multiple lists.

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 demonstrated that participants prefer to reduce the number of to-be-remembered words in order to maximize their recall performance, which ironically results in decreased memory performance. It is possible, however, that participants in the stop condition were subjected to a type of “dual task” paradigm, and that this may have caused the differences in performance. That is, in Experiment 1 the serial position of words was not visible to participants, which raised the possibility that participants may have been mentally tracking the serial position of the presentation to decide the optimal stopping point. This extra mental accounting may have caused suboptimal performance in the stop condition. In Experiment 2, we sought to replicate Experiment 1 and addressed this issue by explicitly indicating the serial position of words. Specifically, a number indicating the serial position was shown alongside each word during the presentation.

Method

Participants

A total of 73 undergraduate students (77% female, mean age = 20.4) from the University of California, Los Angeles participated in the study. Participants were randomly assigned to a stop (N = 39) or a control (N = 34) condition.

Materials

Experimental materials and stimuli randomization algorithm were identical with those in Experiment 1.

Procedure

Experimental procedure was identical with that in Experiment 1, except for one modification: when we presented words in the study session, all of these words were preceded by a number indicating the serial position of the word (e.g., “4. hunter”).

Results and Discussion

On average (Table 1), about half of participants in the stop condition halted the presentation of words before the end of the list (51%, 95% CI = [35.3%, 66.7%]), and this pattern was consistent across the lists (List 1: 51%; List 2: 51%; List 3: 51%; the average rates were the same across the lists but the pattern of stopping across the lists was different across participants), χ2(2) = 0.00, ns. Again, these results indicate that the large portion of participants stopped the presentation of words with the intention to maximize their recall performance. Average serial positions at which they stopped in lists 1–3 were 34.9, 35.0, and 34.0, respectively, and the list effect was not statistically significant, F (2, 76) = 0.12, η2G = .00.

A 2 (Condition: Stop vs. Control) × 3 (List: 1–3) mixed ANOVA on recall memory performance showed the significant main effect of Condition, F (1, 71) = 5.23, p < .05, η2G = .04. Neither the main effect of List, F (2, 142) = 0.47, η2G = .00, nor the interaction between Condition and List, F (2, 142) = 1.03, η2G = .01, was statistically significant (Figure 3). Again, the results showed that participants in the stop condition (M = 6.74, SD = 2.45) remembered the words significantly less than the participants in the control condition (M = 8.04, SD = 2.38). These findings replicated Experiment 1, suggesting that stopping the word presentation before the end of the list undermines memory performance even when serial positions of words are explicitly presented. In fact, when we computed the correlation between the serial position at which participants stopped and their resultant memory performance, all the correlations were positive and statistically significant (r = .45 for List 1, .63 for List 2, .and 63 for List 3, ps < .01). Figure 2B plots the relationship between averaged stopped positions and averaged memory performance across all the lists (r = .64, p < .01).

Figure 3.

Number of correctly remembered items as a function of condition (stop vs. control) and lists (lists 1–3) in Experiment 2. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Experiment 3

Previous experiments showed that participants who were provided with the opportunities to stop the presentations tended to show impaired memory performance relative to the controls. We interpreted these results as people’s inability to maximize their memory performance in a situation where they can decide if and when to stop learning materials. It is also possible, however, that participants in the stop condition were simply distracted by their active engagement in the decision about when to stop the word presentation. That is, participants in the stop condition might have utilized cognitive resources to make a decision, leaving less room or resources for remembering words. Experiment 3 sought to address this possibility. Specifically, Experiment 3 compared a standard stop condition with a “yoked” control condition, where the number of presented words was matched a priori with another participant in the stop condition. This way, participants in the yoked condition could not be distracted by the decision to stop the word presentation, and they were presented with the same number of words as the stop condition. If the decision to stop the word presentation actually reduced the memory performance in the previous experiments, we can expect that participants in the stop condition would show decreased memory performance in comparison to those in the yoked control condition.

Method

Participants

A total of 74 undergraduate students (82% female, mean age = 21.6) from the University of California, Los Angeles participated in the study. Participants were pseudo-randomly assigned to a stop (N = 37) or a yoked control (N = 37) condition; for every two participants, the first participant was assigned to the stop condition and the second participant was assigned to the yoked control condition which was matched to the first participant. As our primary hypothesis may involve the absence of the effect, we attempted to ensure that the sample size provides sufficient statistical power (i.e., .80) to detect the condition effect (with α at .05), based on the effect sizes obtained in Experiments 1 and 2.

Materials

Experimental materials were identical with those in Experiments 1 and 2. The assignment of stimuli to the lists and the order of word presentation were randomized across participants, but within the matched pairs, they were identical.

Procedure

The procedure of the stop condition was identical with that in Experiment 1. Participants in the yoked control condition were presented with the words in the same manner as in the control condition in the previous experiments, but the number of presented words was determined a priori based on the paired participant in the stop condition (therefore, for each pair of participants, the stop condition was always run first). Participants in the yoked control condition were instructed that each list would contain at most 50 words, but that they might be presented with fewer words.

Results and Discussion

Again, on average (Table 1) about half of participants in the stop condition halted the presentation of words before the end of the list (50%, 95% CI = [33.9%, 66.1%]), and this pattern was consistent across the lists (List 1: 41%; List 2: 57%; List 3: 51%), χ2(2) = 2.02, ns. These results indicate that participants had tendency to stop the presentation of words with the intent to maximize their recall performance. Average serial positions at which they stopped in lists 1–3 (those who did not stop the presentation were counted as 50) were 40.2, 35.3, and 37.0, respectively. The effect of List was marginally significant, F (2, 72) = 2.44, p = .095, η2G = .02, but post-hoc multiple comparison tests (Shaffer’s method) did not show any significant differences between the lists (ps > .13).

Importantly, a 2 (Condition: Stop vs. Yoked Control) × 3 (List: 1–3) mixed ANOVA on recall memory performance (M = 7.58, SD = 2.85 for the stop condition; M = 8.04, SD = 2.37, for the control condition) showed no significant main effect of Condition, F (1, 72) = 0.57, p = .45, with a very small effect size (η2G = .00). This result indicates that the opportunity to make a decision to stop the word presentation had little impact on recall performance. The effect of List was statistically significant, F (2, 144) = 3.29, p < .05, η2G = .02, and post-hoc multiple comparison tests showed that recall performance in List 1 (M = 8.34, SD = 3.41) was significantly higher than that in List 2 (M = 7.27, SD = 3.00; p < .05). The interaction between Condition and List was not significant, F (2, 144) = 0.23, η2G = .00.

We again computed the correlation between the serial position at which participants stopped and their resultant memory performance in the stop condition. Replicating previous studies, all the correlations were positive and statistically significant (r = .53 for List 1, .45 for List 2, and .44 for List 3, ps < .01). Figure 2C plots the relationship between averaged stopped positions and averaged memory performance across all the lists (r = .53, p < .01). We also computed the same correlation in the yoked control condition. Note that this is a strong test for the causal relationship between the number of words presented and memory performance; this analysis can control for any potential third variables that contributed to participants’ decision to stop the presentation of words in the stop condition (e.g., prior memory capacity) by using independent participants (i.e., participants in the yoked condition). In other words, the number of presented words was now randomly assigned to participants in the yoked control condition, which allows for stronger causal inference. Remarkably, this restrictive analysis still showed positive significant correlations for List 2 (r = .35, p < .05) and List 3 (r = .49, p < .01), but not for List 1 (r = .13). Figure 2D plots the relationship between averaged stopped positions and averaged memory performance across all the lists (r = .31, p < .05, one tailed). Although the relationships were weaker, the findings provide evidence that participants’ decision to stop before the end of the list in fact adversely influenced their memory performance.

Experiment 4

This series of experiments has shown a strong tendency for participants to stop the presentation of words well in advance of the end of the list, with the belief that this action would help maximize memory performance. One potential problem with these experiments has been that we explicitly specified the maximum number of words presented in the stop condition (i.e., 50). This number may have served as an anchoring point to participants, providing implicit information about whether and when they should stop the presentation. Participants might have guessed, for example, that the optimal stopping point should be slightly before the maximum number of words we provided. To address this possibility, Experiment 4 examines whether and when participants are willing to stop the presentation of words, when there is no explicit specification of the maximum number of words to be presented.

Method

Participants

A total of 28 undergraduate students (61% female, mean age = 20.9) from the University of California, Los Angeles participated in the study. The current experiment had a stop condition only, as our primary focus was to examine whether and when participants stop viewing words without the explicit information about the list length. However, we compared the current results with those from Experiment 1 to facilitate interpretation.

Materials

Experimental materials and stimuli randomization algorithm were identical with those in Experiments 1–3.

Procedure

Experimental procedure was identical with that of the stop condition in Experiment 1, with the exception of one modification. Specifically, participants were not informed of the maximum number of words presented for each list. Instead, they were simply told that they would see a list of “many words.” In fact, if participants did not stop the presentation, it was terminated following the 50th word in each list..

Results and Discussion

On average (Table 1), more than half of participants in the stop condition halted the presentation of words before the end of the list (67%, 95% CI = [49.6%, 84.4%]), and this pattern was consistent across the lists (List 1: 64%; List 2: 68%; List 3: 68%; the average rates were the same across the lists but the pattern of stop across the lists was different across participants), χ2(2) = 0.11, ns. The results corroborated with Experiments 1–3, indicating that the large portion of participants stopped the presentation of words with the intention to maximize their recall performance. These figures are slightly higher than those in Experiment 1 (Table 1), but the difference was not statistically significant (ps > .65). Average serial positions at which they stopped in lists 1–3 were 34.7, 29.6, and 26.3, respectively. The list effect was statistically significant, F (2, 54) = 6.40, p < .01, η2G = .04. However, these figures were not statistically different from those in Experiment 1 (ps > .16). In sum, these findings indicated that explicit information about the maximum number of words for each list played little role in participants’ decision to stop the presentation in our previous experiments.

Although the current experiment did not have a control condition, recall performance was compared with the control condition in Experiment 1 (Figure 3). A 2 (Condition: Stop in the current experiment vs. Control in Experiment 1) × 3 (List: 1–3) mixed ANOVA on recall memory performance was conducted. The main effect of Condition was close to significance and yielded an effect size similar to those in Experiments 1 and 2, F (1, 63) = 3.29, p = .07, η2G = .041. The results suggested that participants in this experiment (i.e., participants who were allowed to stop, M = 7.36, SD = 3.69) remembered the words less than the participants in the control condition in Experiment 1 (M = 8.96, SD = 3.41). Although the comparison with the control condition from a previous study (Experiment 1) is not optimal, these findings again suggest that stopping the word presentation early can undermine memory performance, despite participants’ intentions. To further test this idea, like Experiments 1–3, we also computed the correlation between the serial position at which participants stopped and their resultant memory performance, and all of the correlations were positive and statistically significant (r = .47 for List 1, .59 for List 2, and .41 for List 3, ps < .05). Figure 2E plots the relationship between averaged stopped positions and averaged memory performance across all the lists (r = .54, p < .01).

The main effect of List was statistically significant, F (2, 126) = 3.92, p < .05, η2G = .1, which was mainly driven by the superior memory performance in List 1 than in Lists 2 and 3 (ps < .05, Shaffer’s method). The interaction between Condition and List was not statistically significant, F (2, 126) = 2.51, η2G = .01.

Experiment 5

The results of these experiments have consistently shown that, when exposed to a large amount of information, people make metacognitive judgments to stop receiving more information with the intent to maximize memory performance. But this action is counter to their goals and participants who choose to stop remember fewer words overall. So, why do people want to stop early? As discussed in the introduction, a long word list may overload participants’ short-term memories, and this subjective feeling of difficulty is undoubtedly one of the main reasons for the observed results. On the other hand, the cue-utilization framework (Koriat, 1997) indicates that metacognitive judgments are also partly guided by one’s prior beliefs about memory competence and the ways in which various factors can affect memory performance. In this experiment, we explored the possible role of beliefs in participants’ decisions to stop learning to-be-remembered items. Specifically, we tested whether people are willing to stop the presentation of words before the end of the list even when they are simply presented with a description of the experiment. If people have a belief that restricting the input will increase memory performance, they should indicate their willingness to stop the presentation even without experiencing the encoding of learning materials.

Method

Participants

A total of 108 participants were recruited using Amazon Mechanical Turk (52% female, mean age = 32.2). Sample size was determined by the standard batch size we typically use for our online studies. Participants were randomly assigned to a stop scenario (N = 51) or a control scenario (N = 57) condition.

Procedure

Participants were instructed that they would read the description of a hypothetical memory experiment and they would be asked to indicate their predictions about the hypothetical experiment. The scenarios used for the stop scenario condition and control scenario condition were almost identical to their corresponding conditions in Experiment 1. For both conditions, the only difference from Experiment 1 was that the scenario described a single-list experiment (50 words), rather than a three-list experiment, in order to make participants’ predictions simple.

Participants in the stop scenario condition were told that the goal of the task was to maximize the number of correctly recalled words on a later test, and were asked to indicate on which of the 50 words they would stop the list to achieve that goal. The instructions made it clear that the goal was to maximize the number of, and not the proportion of, the correctly recalled words. They were then asked to predict how many words they would correctly recall during the memory test if they stopped at the number they had indicated. Participants in the control condition were simply asked to predict how many words they would recall out of the 50 word list.

Results and Discussion

Like our previous experiments (i.e., Experiments 1–4), more than half of participants in the stop scenario condition indicated that they would stop the presentation of words before the end of the list (59%, 95% CI = [46.2%, 71.8%]; see Table 1). Average serial positions at which they indicated they would stop was 30.4. This figure is also comparable with the previous experiments (see Table 1). These results suggest that people have general belief that restricting input, to a certain degree, is beneficial for maximizing recall performance.

Predicted memory performance in the stop scenario condition (M = 16.2, SD = 10.9) was substantially larger than that in the previous experiments. This pattern is a typical overconfidence phenomenon. In previous experiments the stop conditions performed consistently lower on memory than the control conditions, but in this experiment the predicted memory performance in the stop scenario condition was not significantly different from the predicted memory performance in the control condition (M = 14.8, SD = 9.6), t (106) = 0.69, p = .49. In fact, the stop scenario condition indicated numerically larger recall performance. These findings provide further evidence that participants were unaware of the possible advantage of viewing all the words in the list to enhance recall performance.

General Discussion

The current study examined people’s metacognitive decisions to stop learning new information and the effects that those decisions have on memory performance. Across the experiments (Experiments 1–4), about half of participants preferred to stop the presentation of items, and even though those participants were attempting to maximize the number of words recalled, the results showed that this metacognitive decision led to impaired memory performance. Indeed, participants who stopped earlier remembered fewer items. It was shown that the impaired memory performance in the stop condition was likely not caused by high task demands due to any decision making or serial monitoring processes (Experiments 2–3). Further, participants’ decisions to stop were not influenced by information about the serial position of words (Experiment 2) or the length of the study list (Experiment 4). Finally, a direct assessment of participants’ metacognitive beliefs (Experiment 5) indicated that the suboptimal metacognitive decision making may be related to a naïve belief that it is possible to maximize the memory performance by restricting the amount of information.

Previous research has suggested that people are fairly good at regulating their memory strategies when they are faced with excessive amounts of learning materials. Specifically, studies indicate that people can flexibly and effectively prioritize learning materials to optimize memory performance (e.g., Ariel et al., 2009; Castel, Benjamin, Craik, & Watkins, 2002; Castel et al., 2011; Castel et al., 2013). The current study, on the other hand, showed that people’s metacognitive regulation can be suboptimal when it comes to the decision of whether we should continue or stop learning further information. On the surface, the results of the current study appear at odds with previous literature on the topic, however, the experimental paradigms used in the past literature (i.e., value-directed remembering paradigms) were mainly concerned with the distribution of attentional resources to learning materials at the item level, specifically value. In contrast, the current stop paradigm addresses metacognitive decision making based on participants’ overall assessment of (or beliefs about) memory capacity. As such, our paradigm examines an aspect of metacognitive self-regulation that is qualitatively different from the memory prioritization research.

Recent studies have also indicated that people can effectively regulate their learning strategies to optimize memory performance. For example, when learners are allowed to self-pace their study of a list of words, there are beneficial effects on memory performance when compared to a control group that was equated on total study time (Tullis & Benjamin, 2011). Further, multiple studies have revealed that participants’ learning was enhanced when they were allowed to control what they restudy (Kornell & Metcalfe, 2006; Nelson, Dunlosky, Graf, & Narens, 1994). The current study also seems to be inconsistent with this line of work. However, these studies provide participants with a fixed number of trials or a fixed amount of study time to learn a set of materials; thus, these studies are not directly comparable to our current study. Future study would benefit from examining how such factors (time, number of trials) interact with people’s decision to stop learning new materials and its resultant learning performance.

Possible Psychological Mechanisms

The current research has established a novel phenomenon in which people tend to make maladaptive decisions to stop encoding new information though the goal is to maximize memory performance. Although we eliminated several alternative explanations for the phenomenon, further in-depth examination of the psychological mechanisms underlying the phenomenon is an important future inquiry.

For example, as suggested in the introduction, mental disfluency due to memory capacity overload is a plausible factor that influenced participants’ decisions to stop receiving further information. This idea is in line with recent findings showing a general tendency to avoid informational or cognitive load (Kool, Mcguire, Rosen, & Botvinick, 2010). Manipulating fluency of to-be-remembered items (e.g., changing font clarity; Yue, Castel, & Bjork, 2013) or directly assessing participants’ metacognitive experiences (e.g., via JOLs) should clarify the role of fluency in participants’ decision to stop the presentation.

Our last experiment (Experiment 5) indicated that participants’ prior beliefs can partly explain the observed findings. Although these findings are suggestive, the precise content of those beliefs is not clear from the experiment. One possibility is that people believe that they can never (or rarely) retrieve learning materials once they are forgotten. This “complete forgetting” view is clearly wrong in light of prominent memory models (e.g., Bjork & Bjork, 1992), but it can explain participants’ behavior in our experiments: participants stopped the presentation of new to-be-remembered items because they overestimated the risk of forgetting in comparison to the benefit of encoding new materials. Experiments that include a short post-experiment survey asking for their strategies or intentions would clarify the nature of participants’ beliefs.

It is also worthwhile to consider that the metacognitive decisions exhibited throughout the current study can be seen as a strong preference for efficiency. That is, instead of selecting against disfluency or discomfort, participants may be selecting for sets that allow for a higher hit to miss ratio at recall. As a set of to-be-remembered items is reduced in size, the proportion of those items that are forgotten at test will likely decrease. In this case selecting against the discomfort imparted by cognitive load is a simultaneous selection for reduced forgetting. A parallel can be drawn with the quantity-quality tradeoff in memory performance. Koriat and Goldsmith (1994, 1996) argued that, in real-life situations, memory quality (i.e., the accuracy of memory performance) is more important than memory quantity. As such, it is possible that participants unconsciously sacrificed quantity for quality, or simply confused quantity with quality, influencing participants’ decisions to stop learning further items in order to ensure the certain level of memory accuracy. Although we attempted to eliminate this possibility by giving incentives for the absolute number of correctly recalled words, future study should explore situations where value in remembering is incredibly salient to address this quantity-quality tradeoff issue.

Our findings can also be discussed in relation to the region of proximal learning model in the literature of self-paced study (Metcalfe, 2009; Metcalfe & Kornell, 2005). The region of proximal learning model indicates that people tend to stop studying an item when they perceive that the rate of learning (the speed of information intake) approaches zero. In fact, Metcalfe and Kornell (2003, 2005) provided empirical evidence that people often avoid spending time on learning very difficult items as these items do not have a sufficiently high learning benefit considering the amount of time it takes to study them (see also labor-in-vain effect; Nelson & Leonesio, 1988). In the current study, participants may have perceived the decreased rate of learning as they went through a long list of items, and this subjective rate of learning may have prompted participants to stop persevering in learning further items. In that sense, although the region of proximal learning model mainly focuses on item-level study time (i.e., how much time people spend on studying each item), our findings can be interpreted as lending support for the model at a more global level (i.e., how much time people spend on studying a long list of items).

Broader Implications

Research has shown that older adults have deficits in various aspects of memory including short-term memory and long-term memory (Kausler, 1994), whereas recent literature indicated that some aspects of metamemory (including prioritization) are preserved or even more pronounced in older adults (Castel et al., 2011; Hertzog & Dunlosky, 2011). Thus, in future research, it is worthwhile to examine age-related similarities and differences in people’s decision to stop or continue to learn. Interestingly, Smith (1979) showed that older adults are less affected by the memory interference due to list-length (i.e., list-length effect). This finding indicates that older adults’ memory may benefit more from a longer list of words, and our paradigm would be able to test whether older adults are aware of this, and can exploit this potential advantage.

Finally, it is worth noting that our findings are in line with the decision making literature on the optimal stopping rule, where researchers typically showed that people tend to gather less information than is optimal to make a decision (e.g., Cox & Oaxaca, 1989; Hey, 1987). In these studies, the participants tended to stop earlier than was optimal. These findings may be partly explained by the results of the current study, which suggest a tendency to prematurely abandon memorizing large amounts of information. The implication of our memory capacity limit in decision making has been documented in the vast literature (e.g., Fiedler, 2000; Gigerenzer & Todd, 1999), but the role of metacognitive belief was not well articulated. Thus, future research would do well to investigate the findings of the current study in relation to a variety of human decision making processes with other forms of materials and inputs, which would provide for a more comprehensive understanding of how our memory and metacognitive systems are tied to decision making.

In conclusion, whereas the literature on metamemory and study strategies is awash with item-level effects, this study addresses a metacognitive approach to the set as a whole. It is common to see studies that explore metacognitive judgments about physical characteristics of the stimuli or external influences that can affect participants’ judgments regarding the stimuli (see Alter & Oppenheimer, 2009), yet here we specifically focus on the characteristics of the set. Importantly, we examined how participants approach a difficult task that feels both overwhelming and impossible because it is too large—memorizing 50 words is no easy feat—and which has many ecologically valid parallels, such as a data-analyst learning a new set of keyboard shortcuts for business software and an executive memorizing client names and professions. In the context of education, it is common that students are faced with an overwhelming amount of learning materials before exams. In cases where there is a seemingly unmanageable amount of information to consider, it appears that participants choose to limit that set, likely as a method of decreasing the discomfort of a “full” mind, but potentially at the dismissal of a superior tactic to maximize overall memory.

Figure 4.

Number of correctly remembered items in Experiment 4 (stop), as compared to that in the control condition in Experiment 1. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by the Marie Curie Career Integration Grant (CIG630680; to Kou Murayama), JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 15H05401; to Kou Murayama), and the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging; Award Number R01AG044335; to Alan Castel).

Footnotes

There was one participant whose memory performance was exceptionally high (i.e., 3.4 SD above the mean). Without that participant, the main effect of the condition was statistically significant, F (1, 62) = 5.65, p = .02, η2G = .07.

References

- Adcock RA, Thangavel A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Knutson B, Gabrieli JDE. Reward-motivated learning: Mesolimbic activation precedes memory formation. Neuron. 2006;50:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel R, Dunlosky J, Bailey H. Agenda-based regulation of study-time allocation: when agendas override item-based monitoring. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2009;138:432–447. doi: 10.1037/a0015928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RC, Shiffrin RM. Human memory: a proposed system and its control processes. In: Spence KW, Spence JT, editors. The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1968. pp. 89–195. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Hitch GJ. Working memory. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. 1974;8:47–89. doi: 10.1016/s0079-7421(08)60452-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Yap MJ, Cortese MJ, Hutchison KA, Kessler B, Loftis B, Neely JH, Nelson DL, Simpson GB, Treiman R. The English lexicon project. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:445–459. doi: 10.3758/bf03193014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA, Bjork EL. A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In: Healy A, Kosslyn S, Shiffrin R, editors. From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA, Dunlosky J, Kornell N. Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2013;64:417–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne GJ, Pitts MG. Stopping rule use during information search in design problems. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2004;95:208–224. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C, Lund K. Modeling parsing constraints with high dimensional context space. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1997;12:117–210. doi: 10.1080/016909697386844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cary M, Reder LM. A dual-process account of the list-length and strength-based mirror effects in recognition. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;49:231–248. doi: 10.1016/S0749-596X(03)00061-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD. Metacognition and learning about primacy and recency effects in free recall: The utilization of intrinsic and extrinsic cues when making judgments of learning. Memory & Cognition. 2008;36:429–437. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Benjamin AS, Craik FIM, Watkins MJ. The effects of aging on selectivity and control in short-term recall. Memory & Cognition. 2002;30:1078–1085. doi: 10.3758/bf03194325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Humphreys KL, Lee SS, Galvan A, Balota DA, McCabe DP. The development of memory efficiency and value-directed remembering across the life span: A cross-sectional study of memory and selectivity. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1553–1564. doi: 10.1037/a0025623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Murayama K, Friedman MC, McGillivray S, Link I. Selecting valuable information to remember: Age-related differences and similarities in self-regulated learning. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:232–242. doi: 10.1037/a0030678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. Evolving conceptions of memory storage, selective attention, and their mutual constraints within the human information-processing system. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104:163–191. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.104.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Oaxaca R. Laboratory experiments with a finite-horizon job-search model. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1989;2:301–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00209391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue JR. Implementing Shaffer’s multiple comparison procedure for a large number of groups. In: Benjamini Y, Bretz F, Sarkar S, editors. Lecture Notes-Monograph Series: Vol. 47, Recent Developments in Multiple Comparison Procedures. Institute of Mathematical Statistics; 2004. pp. 1–23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlosky J, Thiede KW. What makes people study more? An evaluation of factors that affect self-paced study. Acta Psychologica. 1998;98:37–56. doi: 10.1016/S0001-6918(97)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K. Beware of samples! A cognitive-ecological sampling approach to judgment biases. Psychological Review. 2000;107:659–676. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MC, McGillivray S, Murayama K, Castel AD. Memory for medication side effects in younger and older adults: The role of subjective and objective importance. Memory & Cognition. 2015;43:206–215. doi: 10.3758/s13421-014-0476-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Kornell N. Collector [Software] 2014 Available from https://github.com/gikeymarcia/Collector.

- Gigerenzer G, Todd PM. Simple heuristics that make us smart. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Dunlosky J. Metacognition in later adulthood: Spared monitoring can benefit older adults’ self-regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20:167–173. doi: 10.1177/0963721411409026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey JD. Still searching. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 1987;8:137–144. doi: 10.1016/0167-2681(87)90026-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HKS, Pashler H. Is the benefit of retrieval practice modulated by motivation? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 2014;3:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH. Learning and memory in normal aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnell A, Dennis S. The list length effect in recognition memory: An analysis of potential confounds. Memory & Cognition. 2011;39:348–363. doi: 10.3758/s13421-010-0007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool W, McGuire JT, Rosen ZB, Botvinick MM. Decision making and the avoidance of cognitive demand. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2010;139:665–682. doi: 10.1037/a0020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A. Monitoring one’s own knowledge during study: A cue-utilization approach to judgments of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General. 1997;126:349–370. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.126.4.349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A, Goldsmith M. Memory in naturalistic and laboratory contexts: Distinguishing the accuracy-oriented and quantity-oriented approaches to memory assessment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1994;123:297–315. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.123.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A, Goldsmith M. Monitoring and control processes in the strategic regulation of memory accuracy. Psychological Review. 1996;103:490–517. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, Bjork RA. Optimising self-regulated study: The benefits—and costs—of dropping flashcards. Memory. 2008;16:125–136. doi: 10.1080/09658210701763899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, Metcalfe J. Study efficacy and the region of proximal learning framework. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32:609–622. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Aklin WM, Zvolensky MJ, Pedulla CM. Evaluation of the balloon analogue risk task (bart) as a predictor of adolescent real-world risk-taking behaviours. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:475–479. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(03)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray S, Castel AD. Betting on memory leads to metacognitive improvement by younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:137–142. doi: 10.1037/a0022681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J. Metacognitive judgment and control of study. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, Kornell N. The dynamics of learning and allocation of study time to a region of proximal learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:530–542. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, Kornell N. A region of proximal learning model of study time allocation. Journal of Memory and Language. 2005;52:463–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2004.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama K, Kitagami S. Consolidation power of extrinsic rewards: Reward cues enhance long-term memory for irrelevant past events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143:15–20. doi: 10.1037/a0031992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama K, Sakaki M, Yan VX, Smith GM. Type-1 error inflation in the traditional by-participant analysis to metamemory accuracy: A generalized mixed-effects model perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2014;40:1287–1306. doi: 10.1037/a0036914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TO, Dunlosky J, Graf A, Narens L. Utilization of metacognitive judgments in the allocation of study during multitrial learning. Psychological Science. 1994;5:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00502.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TO, Leonesio RJ. Allocation of self-paced study time and the “labor-in-vain effect”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1988;14:676–686. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.14.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale DA, Rapoport A. Sequential decision making with relative ranks: An experimental investigation of the “secretary problem”. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1997;69:221–236. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1997.2683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffrin RM. Capacity limitations in information processing, attention, and memory. In: Estes WK, editor. Handbook of learning and cognitive processing. vol. 4: Attention and memory. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1976. pp. 177–236. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD. The interaction between age and list length in free recall. Journal of Gerontology. 1979;34:381–387. doi: 10.1093/geronj/34.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son LK, Kornell N. Research on the allocation of study time: Key studies from 1890 to the present (and beyond) In: Dunlosky J, Bjork RA, editors. A handbook of memory and metamemory. Hillsdale, NJ: Psychology Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol J, Schain C, Bowen HJ. Reward-enhanced memory in younger and older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014;69:730–740. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauber SK, Rhodes MG. Does the amount of material to be remembered influence judgements of learning (jols)? Memory. 2010;18:351–362. doi: 10.1080/09658211003662755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis JG, Benjamin AS. On the effectiveness of self-paced learning. Journal of Memory and Language. 2011;64:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood BJ. Recognition memory as a function of length of study list. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1978;12:89–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03329636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward G. A recency-based account of the list length effect in free recall. Memory & Cognition. 2002;30:885–892. doi: 10.3758/BF03195774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue CL, Castel AD, Bjork RA. When disfluency is—and is not—a desirable difficulty: The influence of typeface clarity on metacognitive judgments and memory. Memory & Cognition. 2013;41:229–241. doi: 10.3758/s13421-012-0255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]