Abstract

Study Objectives:

To assess the clinical relevance of sleep duration, hours slept were compared by health status, presence of insomnia, and presence of depression, and the association of sleep duration with BMI and cardiovascular risk was quantified.

Methods:

Cross-sectional analysis of subjects in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys using adjusted linear and logistic regressions.

Results:

A total of 22,281 adults were included, 37% slept ≤ 6 hours, 36% were obese, and 45% reported cardiovascular conditions. Mean sleep duration was 6.87 hours. Better health was associated with more hours of sleep. Subjects with poor health reported sleeping 46 min, (95% CI −56.85 to −35.67) less than subjects with excellent health. Individuals with depression (vs. not depressed) reported 40 min less sleep, (95% CI −47.14 to −32.85). Individuals with insomnia (vs. without insomnia) reported 39 min less sleep, (95% CI −56.24 to −22.45). Duration of sleep was inversely related to BMI; for every additional hour of sleep, there was a decrease of 0.18 kg/m2 in BMI, (95% CI −0.30 to −0.06). The odds of reporting cardiovascular problems were 6.0% lower for every hour of sleep (odds ratio = 0.94, 95% CI [0.91 to 0.97]). Compared with subjects who slept ≤ 6 h, subjects who slept more had lower odds of reporting cardiovascular problems, with the exception of subjects ≥ 55 years old who slept ≥ 9 hours.

Conclusions:

Long sleep duration is associated with better health. The fewer the hours of sleep, the greater the BMI and reported cardiovascular disease. A difference of 30 minutes of sleep is associated with substantive impact on clinical well-being.

Citation:

Cepeda MS, Stang P, Blacketer C, Kent JM, Wittenberg GM. Clinical relevance of sleep duration: results from a cross-sectional analysis using NHANES. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(6):813–819.

Keywords: sleep, NHANES, health, cardiovascular risk, obesity, observational research

INTRODUCTION

Poor quality sleep and reduction in sleep duration have been shown to have a negative impact on health as well as to interfere with daily functioning.1–3 Reduced sleep duration has been associated with weight gain, increased risk of a number of illnesses, and increased mortality.4–6

Sleep loss affects the interactions between biological arousal and metabolic systems in the hypothalamus,7 perturbs the functioning of the complex communication network between the brain and the immune system through sympathetic overstimulation, hormonal imbalance and elevation of inflammatory mediators,8 and increases Aβ levels leading to increased amyloid plaque accumulation implicating it in the development of dementia.4 These pathways affected by sleep disturbances help explain the association of sleep loss with obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, dementia, and other chronic conditions.9,10

These data support the widely held belief that not getting enough sleep is detrimental to health, but it remains unclear as to whether there is a threshold that distinguishes and predicts the amount of sleep necessary to impact health outcomes and mortality.11 Some of this controversy arises from the lack of agreement as to what a “normal” amount of sleep should be. Elucidating the relation between sleep duration and certain medical conditions, general health, and well-being may inform our understanding of the clinical relevance of specific changes in sleep duration.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: The importance of sleep duration needs to be further elucidated. We sought to assess the clinical relevance of sleep duration in a representative sample of the US population. This is a cross-sectional analysis of subjects in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Study Impact: We found that better health is associated with longer duration of sleep. Fewer hours of sleep resulted in greater BMI and cardiovascular risk. A difference of 30 minutes of sleep is associated with a substantive change in clinical well-being.

In order to describe the relation between sleep duration, clinical conditions, and the impact of changes in sleep duration on health, we sought to: (1) assess the clinical relevance of sleep duration by determining the difference in sleep duration in subjects with different general health status, and in subjects with insomnia and depression; and (2) quantify the form of the association of sleep duration with weight and with the risk of cardiovascular problems by assessing body mass index (BMI) as a continuous and categorical variable in a general sample of the US population.

METHODS

We designed and conducted a cross-sectional analysis using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES is a research program that collects health information about the US population through interviews, medical examinations, and lab tests.12 Results of analysis of NHANES data are representative of the non-institutionalized US population.12 We included subjects ≥ 21 years old who participated in NHANES in 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010, and 2011 and 2012 and responded to any of the sleep questions.

Sleep Measures

Duration of sleep was captured by a single question in NHANES: “How much sleep do you usually get at night on weekdays or workdays?” The response categories range from 1 to 12 with 12 indicating that the participant gets 12 hours or more of sleep.

Sleep duration was analyzed in 2 ways: as a continuous and as a categorical variable. The categories, ≤ 6 h, > 6 to < 9 h, ≥ 9 h, based on prior research,13–15 avoid the assumption of linearity between sleep duration, weight, and cardiovascular risk.

NHANES in 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 contained additional questions about sleep habits including a subscale of 8 questions related to general productivity from the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire.16

To classify a subject as having insomnia, we used the responses to the frequency of insomnia symptoms and impairment in various areas of functioning; since the diagnosis was not made by a health professional, we refer to it as sleep insufficiency with interference. The questions included the following insomnia symptoms: trouble falling asleep, waking up during the night, waking up too early in the morning, not feeling rested during the day, feeling overly sleepy the during day, and not getting enough sleep. A respondent was considered to have an insomnia symptom if they reported symptom occur-rence in either of the 2 highest categories of frequency (often: 5–15 times a month or almost always: 16–30 times a month). To classify an individual as having sleep insufficiency with interference, we required that they have frequency ≥ 5 times a month in addition to moderate or extreme difficulty in ≥ 2 areas of functioning: concentrating, remembering, eating, hobby activities, getting things done, doing finances, working, and phone conversations. This classification is consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth edition (DSM-IV) definition of insomnia.1,17

Body Measurements

NHANES participants had their weight and height measured by trained health technicians. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

BMI was analyzed in 2 ways: as a continuous variable and as categorical variable. Four BMI categories were utilized: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.6–24.9 kg/m2), over-weight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2).18 Categories of BMI were used to avoid making an assumption of a linear association between BMI and the outcome.

Health Status, Definition of Cardiovascular Condition and Other Medical Conditions

NHANES captures a broad range of self-reported health conditions in the general form of “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had a [name of medical condition]?” If an individual reported angina, congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, we classified them as having a cardiovascular disease.

A participants' health status was determined by their answer to the question: “Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?”

Depression was measured in NHANES with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This is a 9-item tool that asks participants to choose 1 of 4 responses about the frequency of depressive symptoms during the previous 2 weeks.19 Subjects were classified as having depression if PHQ-9 scores were ≥ 10. Scores ≥ 10 represent moderate or severe depressive symptoms.20 We also considered a stricter definition of depression which, in addition to a score ≥ 10, the subject had to have responded “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” to the question: “How often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?”

Race is reported in NHANES as: African American, White, and other. Smokers were classified as: current smoker: participant who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in lifetime and currently smoke every day or some days; former smoker: a participant who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in lifetime but does not currently smoke; and never smoked: a participant who never smoked 100 cigarettes in lifetime. We grouped the medical conditions reported in NHANES into 17 categories and totaled the number of such conditions for each participant (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, renal disease, respiratory disease).

Statistical Methods

Association of Hours of Sleep with General Health Status

To assess the clinical relevance of sleep duration, we calculated both unadjusted and adjusted differences in duration of sleep by health status level. We used a self-report of “excellent health” as the reference category. Age, sex, and race adjusted results were derived by constructing a linear regression model, with duration of sleep as the outcome variable and self-report of overall health status and potential confounders as covariates.

To further understand the clinical relevance of duration of sleep, we also calculated the difference in duration of sleep in subjects with and without sleep insufficiency with interference and in subjects with and without depression.

Association of Duration of Sleep with Weight

To assess the association of duration of sleep with BMI, we built unadjusted and adjusted linear regressions and ordinal logistic models. In the linear regression models, the outcome was BMI. In the ordinal logistic regression, the outcome was BMI category. In all of these models, hours of sleep were analyzed as a continuous variable or as categorical variable. In the adjusted analysis, potential confounders were added: age, age squared, gender, race, problems that limited activity, diabetes, smoking status, and number of medical conditions. In the ordinal logistic regression, odds ratios (ORs) are reported.

Because the impact of duration of sleep on weight could vary depending on the age of the subject, we added to the linear and logistic regression models the interaction between age, categorized as < 55 and ≥ 55, and the 3 sleep categories. Results are reported overall and by age.

Association of Duration of Sleep with Cardiovascular Risk

To assess the association of duration of sleep with cardiovascular risk, we built unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models with a binary outcome for having a cardiovascular condition (Yes/No). In these models, duration of sleep was analyzed as a continuous variable or as a categorical variable. In the adjusted analysis, potential confounders were added: age, gender, race, BMI, diabetes, smoking status, and history of high cholesterol.

Because the impact of duration of sleep on cardiovascular risk could vary depending on the age of the subject, we added to the logistic regression model the interaction between age, categorized as < 55 and ≥ 55, and the 3 sleep categories. Results are reported overall and by age.

Incorporating Complex Survey Design in the Analysis

To correctly account for the complex survey design, the analyses included the Primary Sampling Unit variable (sdmvpsu) as the stratification variable (sdmvstra) and the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) exam variable (wtmec2y) as the weight variable. We multiplied the weight variable by 1/4, because we included 4 survey periods. STATA version 12.1 was used to conduct the analyses.

RESULTS

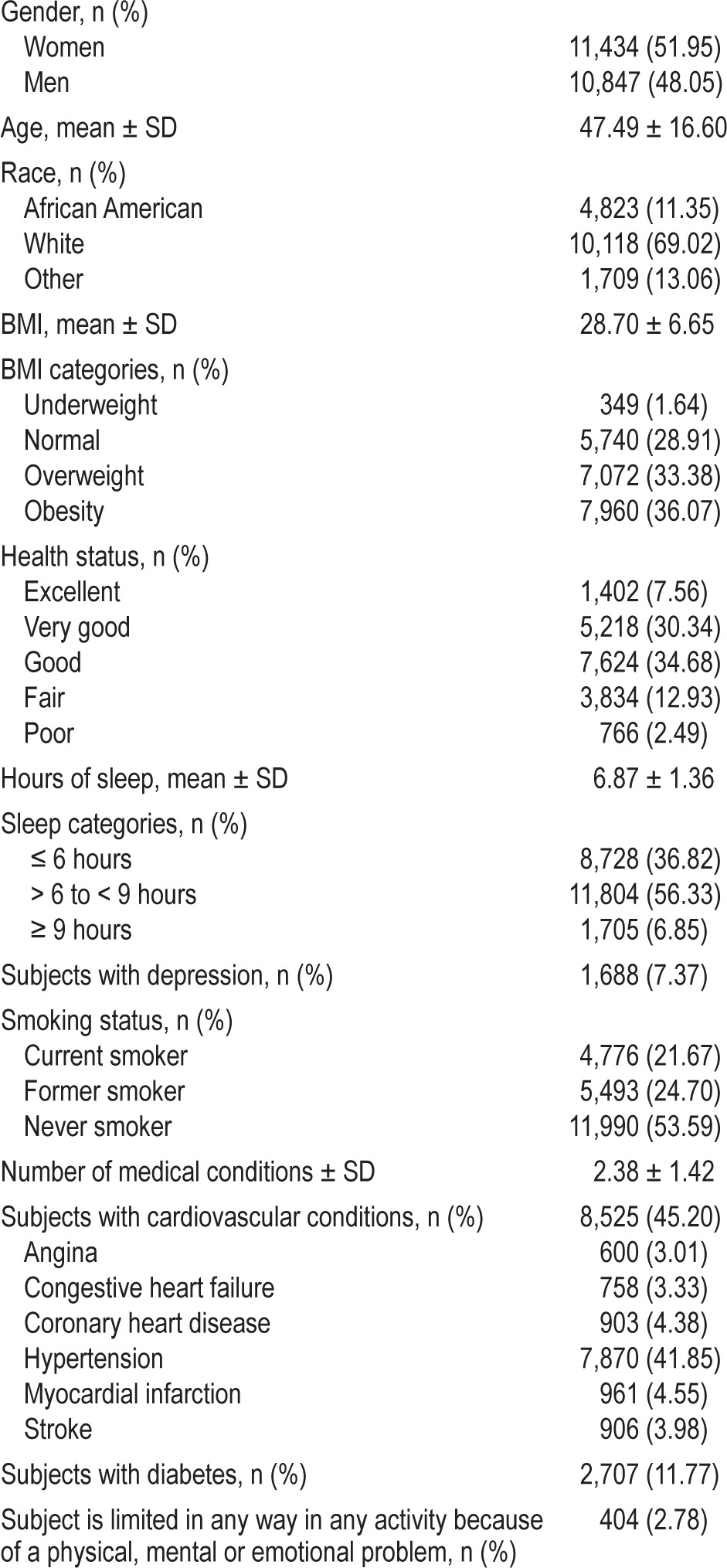

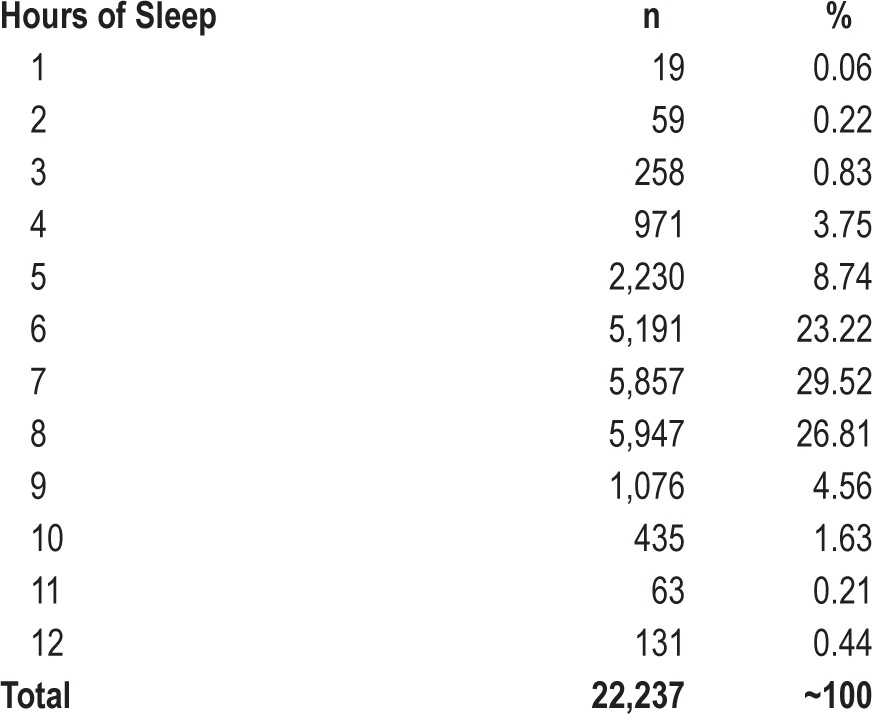

A total of 22,281 participants were included in the analysis. The mean age was 47.49 years; there were slightly more women; and almost 70% were overweight or obese, with 36% meeting or exceeding the cutoff for obesity. Forty-five percent of the subjects reported having a cardiovascular condition, with hypertension being the most common. Subjects reported a mean duration of nighttime sleep during weekdays of 6.87 h, however almost 37% of the subjects reported sleeping ≤ 6 h (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included subjects.

Table 2.

Number of hours slept at night on weekdays or workdays.

The distributions of BMI and hours of sleep were not skewed (skewness = 1.37 and −0.12, respectively); therefore, there was no need for conducting any transformation to approximate normality.

Association of Hours of Sleep with General Health Status, Sleep Insufficiency with Interference, and Depression

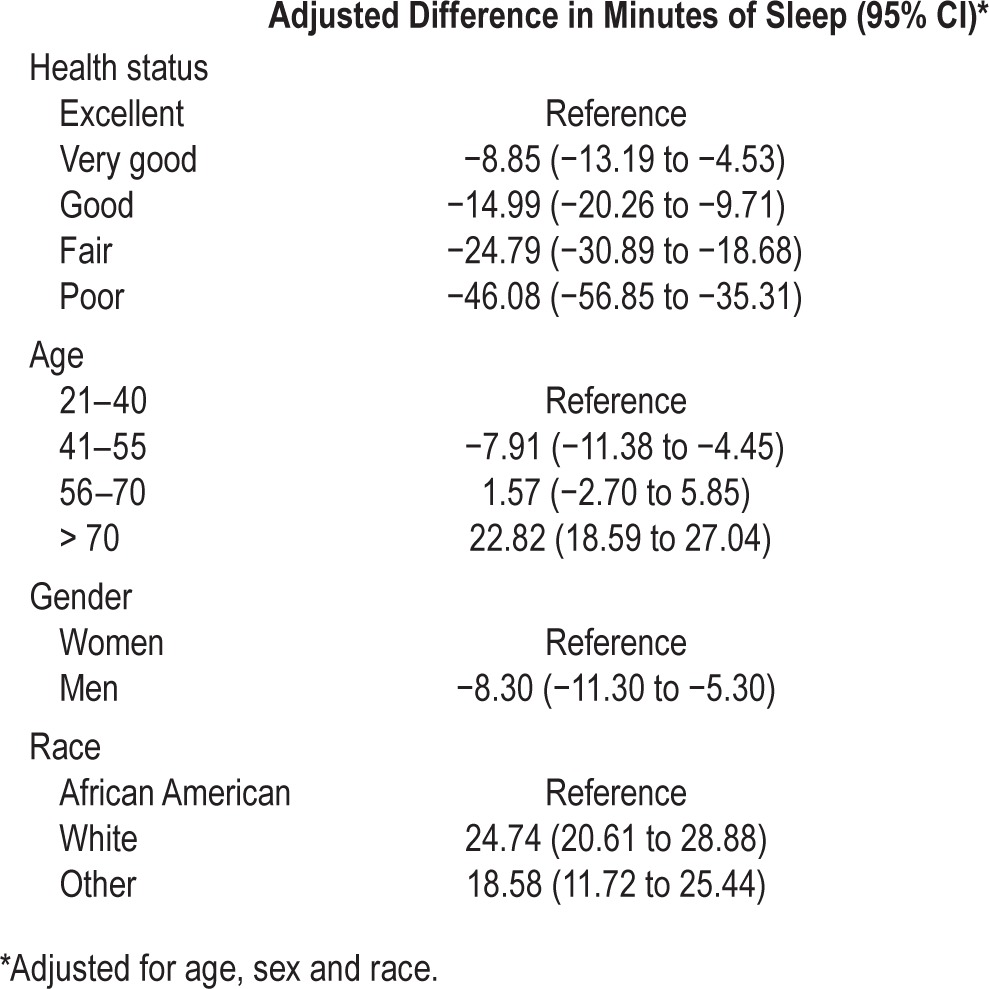

Almost 38% of the subjects rated their health as “very good” or “excellent,” and 15% rated their health as “fair” or “poor.” The better the self-rated health of the participant, the more hours of sleep reported (Table 2). The difference in duration of sleep between subjects with poor self-reported health and subjects with excellent health was 45 minutes. After adjustment by age, gender and race, this relation remained (46 minutes [95% Confidence interval (CI) −56.85 to −35.67]) (Table 2).

Women were likely to sleep more hours than men; whites were likely to sleep more hours than African Americans; and older participants (> 70) were likely to sleep more hours than younger subjects, Table 3.

Table 3.

Health status, age, gender and race, and duration of sleep.

Seven percent of the participants were classified as depressed using the PHQ-9 criteria (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10). Depressed individuals reported a shorter mean duration of sleep, a difference of 40 minutes, (95% CI −47.14 to −32.85) compared to those who were not depressed.

Using the stricter definition of depression (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 and report of feeling down, depressed, or hopeless more than half the days or nearly every day), 4.21% of the subjects were depressed. Individuals who met the stricter definition also had a shorter mean duration of sleep, a difference of 36 min (95% CI −45.39 to −26.41) compared to those who were not classified as depressed.

Of the 10,729 participants who responded to the more detailed sleep disturbance questions, 47.44% reported having symptoms of insomnia and approximately 3.19% were classified as having sleep insufficiency with interference which includes subjects who reported not only symptoms of insomnia, but also at least moderate difficulty with daily activities. Sleep insufficiency with interference and depression were strongly associated, (OR = 12.91, 95% CI 9.82 to 16.97). The difference in duration of sleep between subjects with and without sleep insufficiency with interference was 39 min (95% CI −56.24 to −22.45).

Association of Duration of Sleep with Weight

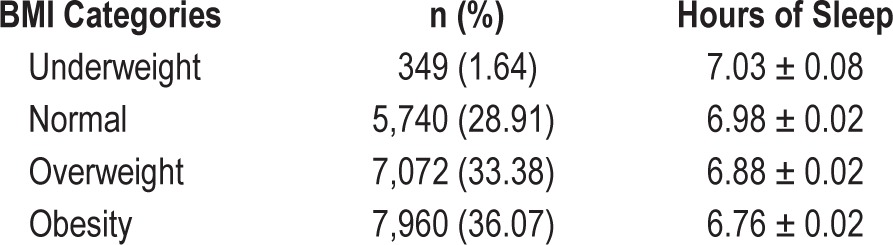

As the hours of sleep decreased, BMI increased (Table 4). Without adjustment, every hour of sleep was associated with a decrease in 0.38 kg/m2 in BMI. After adjustment, the magnitude of the association decreased, but remained statistically significant. For every additional hour of sleep, there was a decrease of 0.18 kg/m2 in BMI (95% CI −0.30 to −0.06).

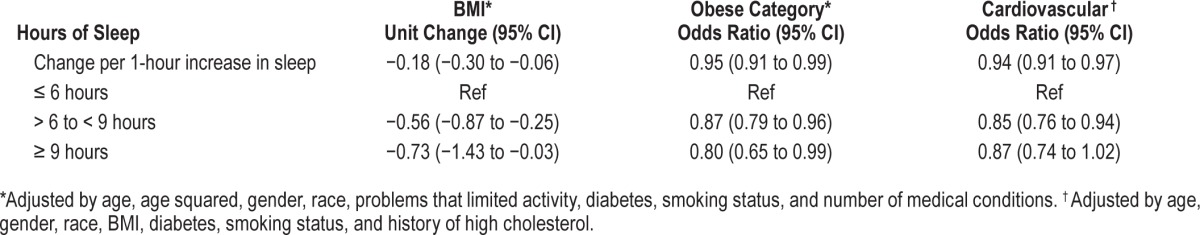

Table 4.

Weight and duration of sleep

The analysis of the association of BMI and sleep, based on the categorical variable of sleep, provided similar results. Compared with subjects who slept ≤ 6 h, subjects who slept > 6 to < 9 h or ≥ 9 h had lower mean BMI before and after adjustment, (Table 5).

Table 5.

Adjusted association of hours of sleep at night with BMI and cardiovascular risk.

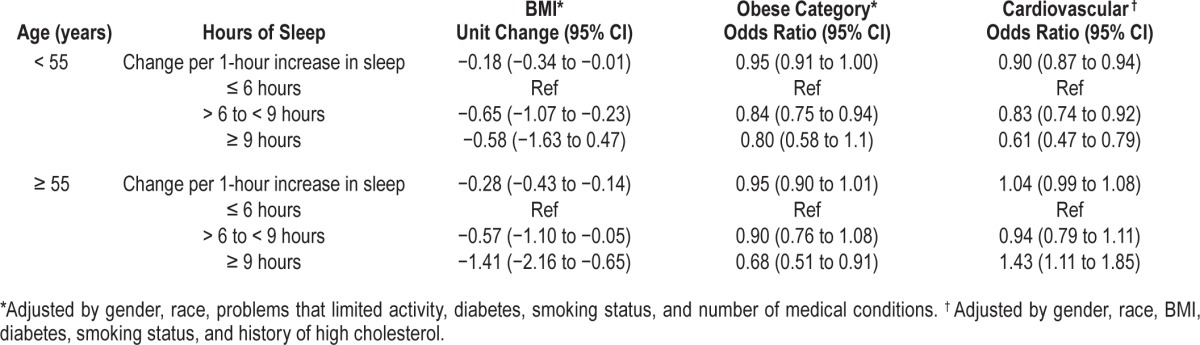

None of the interactions between age and sleep categories was statistically significant, p value = 0.3 for both. The stratified analysis by age showed similar results to the results of the linear regression for the overall population (Table 6).

Table 6.

Adjusted association of hours of sleep at night with BMI and cardiovascular risk in subjects < 55 and in subjects ≥ 55 or older.

The ordinal logistic regression analysis, in which the outcome variable was BMI category, provided similar results as well. Every hour of sleep was associated with 5.0% lower odds of being in the obese category. Compared with subjects who slept ≤ 6 h, subjects who slept > 6 to < 9 or ≥ 9 h had lower odds of being in the obese category (13% and 20% lower, respectively) after adjustment (Table 5).

None of the interactions between age and sleep categories was statistically significant, p value = 0.1 for sleep cat -egory > 6 to < 9 h and ≥ 55 years of age and p value = 0.7 for sleep category ≥ 9 h and ≥ 55 years of age. The stratified analysis by age showed similar results to the results of the ordinal logistic regression for the overall population.

Association of Duration of Sleep with Cardiovascular Risk

The odds of reporting cardiovascular problems decreased 3.0% for every hour of sleep. After adjustment, the odds of reporting cardiovascular problems were 6.0% lower for every hour of sleep.

When sleep was included as a categorical variable, instead of a continuous variable, the results were similar. Compared with subjects who slept ≤ 6 h, subjects who slept > 6 to < 9 or ≥ 9 h had lower odds of having cardiovascular problems (after adjustment, OR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.76 to 0.94]) (Table 5).

The interaction between the ≥ 9-h sleep category and age ≥ 55 was highly statistically significant, p < 0.0001, indicating that the association of sleeping ≥ 9 h and risk of cardiovascular disease depends on age. The stratified analysis by age showed that the odds of having cardiovascular disease were 43% higher in subjects ≥ 55 or older who reported ≥ 9 h sleep compared with subjects in the same age category who slept ≤ 6 h (see Table 6). In younger subjects (< 55), the odds of having cardiovascular disease were higher in subjects who reported sleeping ≤ 6 h than in subjects who reported sleeping > 6 to < 9 or ≥ 9 hours.

The NHANES database is a publicly available resource for use by researchers throughout the world. No permission or institutional review board approval is needed to access NHANES data.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis on a large, representative US population sample to understand the relevance of sleep duration as it applies to health status. We found a clear dose-response between sleep duration and health status: the more hours of sleep, the better the overall self-reported health. The study findings suggest that 30 minutes of additional sleep is clinically relevant.

Symptoms of insomnia were frequent in the general population, however, a much smaller number had sleep insufficiency with interference, defined as having significant sleep symptoms and impairment in functioning. The difference in sleep duration between subjects with and without sleep insufficiency with interference and with and without depression further corroborates that a difference in 30 minutes of sleep is clinically relevant and distinguishes different levels of impairment.

Our study confirms previous findings on the association between duration of sleep and increased weight.13–15,21–23 The fewer the hours of sleep, the greater the BMI. The magnitude of the association between sleep and BMI in the present study is smaller than the one reported in a meta-analysis, but only for subjects < 55 years of age.23 A high degree of heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis and no data by age of study participants was presented. The association between sleep and weight is clinically relevant. As the units of BMI can be difficult to interpret, we can use kilograms to place the results in perspective. The findings are equivalent to a decrease in 0.5 kilos per additional hour of sleep in a person whose height is 1.68 meters.

Contrary to other studies, the findings of the present study do not support the U-shaped association between weight and sleep, where sleep durations longer than 7–7.5 hours were associated with obesity.24 We found that subjects who slept ≥ 9 hours still had 20% lower odds of being obese than subjects who slept ≤ 6 hours. A previous study conducted in NHANES in the early 1980s found that the association between duration of sleep and obesity was only present for subjects with sleep durations of 7 hours or less.22 This discrepancy can be explained by the much larger sample size in the present study, 8,073 subjects vs 22,281.

We found that sleep duration is negatively associated with cardiovascular risk as the more hours of sleep, the lower the risk of reporting cardiovascular disease. These findings support findings from other studies.25–27 We found that sleeping ≥ 9 hours was associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease as other research suggest,26,27 but only for subjects 55 years or older. The study by Gottlieb26 that was based on the Sleep Heart Health Study included subjects who were on average 20 years older and does not report study results by age, and the meta-analysis authors were unable to stratify by age due to inconsistent reporting of age in the included studies.27 Our study suggests that individuals younger than 55 years of age who reported sleeping > 9 hours, as well as those who reported sleeping > 6 hours, had lower risk of cardiovascular disease than subjects the same age who reported sleeping ≤ 6 hours.

Insomnia has been linked to an increase in the risk of developing cardiovascular disease or dying from cardiovascular disease.28,29 We did not assess mortality, but we analyzed general health status, which has been linked to mortality.30,31 We observed that as self-report of general health deteriorated, subjects reported less sleep.

This study is a cross-sectional study, which limits the ability to measure temporality, and therefore causality cannot be assessed. We can only state that there is an association between hours of self-reported sleep and self-reported health status and cardiovascular disease. Another limitation is that duration of sleep was self-reported and self-reporting information is less accurate than objective measures.32 Subjects overestimate the number of hours they sleep,32 and this bias could lead to misclassification and likely to an underestimation of the association between sleep and the outcome.

In summary, duration of sleep is associated with weight and cardiovascular disease; the fewer hours of sleep, the greater the weight and the risk of cardiovascular conditions. Better health is associated with longer duration of sleep. A difference in 30 minutes of sleep appears to be clinically relevant.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors are employees of Janssen Research & Development. The manuscript makes no reference to any commercial product.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- ORs

odds ratios

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:S7–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth T, Roehrs T. Insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequences. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(03)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999;354:1435–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ju YE, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, et al. Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:587–93. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sigurdson K, Ayas NT. The public health and safety consequences of sleep disorders. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:179–83. doi: 10.1139/y06-095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Léger D, Beck F, Richard J-B, Sauvet F, Faraut B. The risks of sleeping “too much”. survey of a national representative sample of 24671 adults (INPES Health Barometer) PLoS One. 2014;9:e106950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolls A, Schaich Borg J, de Lecea L. Sleep and metabolism: role of hypothalamic neuronal circuitry. Best Pract Res Clin Endrocrinol Metab. 2010;24:817–28. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullington JM, Simpson NS, Meier-Ewert HK, Haack M. Sleep loss and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endrocrinol Metab. 2010;24:775–84. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motivala SJ. Sleep and inflammation: psychoneuroimmunology in the context of cardiovascular disease. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:141–52. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma S, Kavuru M. Sleep and metabolism: an overview. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:270832. doi: 10.1155/2010/270832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Cappuccio FP, et al. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep. 2007;30:1659–66. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health and nutrition examination survey. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

- 13.Xiao Q, Arem H, Moore SC, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. A large prospective investigation of sleep duration, weight change, and obesity in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1600–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel SR, Hu FB. Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:643–53. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anic GM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Egan KM. Sleep duration and obesity in a population-based study. Sleep Med. 2010;11:447–51. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005 - 2006 Data documentation, codebook, and frequencies / Sleep disorders. 2005. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/SLQ_D.htm.

- 17.Roth T, Jaeger S, Jin R, Kalsekar A, Stang PE, Kessler RC. Sleep problems, comorbid mental disorders, and role functioning in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. 1998. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/obesity_guidelines_archive.pdf. [PubMed]

- 19.Shim RS, Baltrus P, Ye J, Rust G. Prevalence, treatment, and control of depressive symptoms in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005-2008. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:33–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magee CA, Iverson DC, Huang XF, Caputi P. A link between chronic sleep restriction and obesity: methodological considerations. Public Health. 2008;122:1373–81. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Boden-Albala B, Heymsfield SB. Inadequate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: analyses of the NHANES I. Sleep. 2005;28:1289–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, et al. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31:619–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall NS, Glozier N, Grunstein RR. Is sleep duration related to obesity? A critical review of the epidemiological evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford ES. Habitual sleep duration and predicted 10-year cardiovascular risk using the pooled cohort risk equations among US adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001454. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottlieb DJ, Redline S, Nieto FJ, et al. Association of usual sleep duration with hypertension: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2006;29:1009–14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1484–92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sofi F, Cesari F, Casini A, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF. Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:57–64. doi: 10.1177/2047487312460020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:267–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abrutyn E, Mossey J, Berlin JA, et al. Does asymptomatic bacteriuria predict mortality and does antimicrobial treatment reduce mortality in elderly ambulatory women? Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:827–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-10-199405150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology. 2008;19:838–45. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187a7b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]