“The Dane in Spain was mainly on the Dane.”1 These words were spoken by the late Dr Robbie Morton, drawing on three decades' experience in venereology, about the sexual behaviour of holidaymakers and their risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs) while abroad. Despite Morton's years of clinical expertise his opinion would not survive the rigours of evidence based guidelines and at best would be graded as level 4, if at all. So is his assumption that sexual encounters while on holiday tend to be between people of the same nationality correct? What are the implications of international mixing on the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections? How should we manage people at risk before and after their holiday?

Methods

I searched Medline in November 2003, using the key words “sexually transmitted infection”, “abroad”, “tourist”, “holiday”. I reviewed websites of the Health Protection Agency, the World Health Organization, the Department of Health, the Foreign Office, and the Association of British Travel Agents as these could be expected to provide information on travel abroad. Clinical information is from Sexually Transmitted Diseases.2

Sexual behaviour abroad and acquisition of STIs

More than 30 million UK residents travel abroad each year.3 Sexual activity is known to vary by season; increased sexual intercourse and unsafe sex occur around the Christmas period and the summer vacation.4 Holidays are increasingly being taken abroad and in far flung locations, and the number of UK residents travelling abroad has increased by 27% since 1997.5 Holidays provide an opportunity for increased sexual mixing whether taken at home or abroad (fig 1, fig 2). Few recent data exist on sexual behaviour while on holiday abroad, and even fewer for people holidaying in the United Kingdom. Studies in the early 1990s showed notable risk behaviour in international travellers who attended for a “tropical check.”6 People from developed countries had sex primarily with someone also from a developed country (56%). Of those people with an STI who attended a clinic for genitourinary medicine (GUM) who had travelled abroad in the preceding three months, 25% reported a new partner while away and two thirds had not or inconsistently used condoms.7 A more recent study found that 32% of medical students had sexual intercourse with a new partner while on holiday.8 Gay and heterosexual men attending GUM clinics in Glasgow were more likely to have sex with a local partner while on holiday than other groups.9 The number of new sexual encounters per week was 0.098 before the holiday and 0.247 while away, which implies that travel is an independent predictor of increased sexual activity. Of British holidaymakers in Tenerife, 35% had sexual intercourse with a non-regular partner while on holiday.10 Men (32%) were no different from women (39%) with regard to having a new partner, but people aged 25 or younger were more likely to have a new sexual partner than those older than 25 (50% v 22%). Women were more likely than men to have sex with non-British partners (13/30, 43%, v 6/32, 19%; Batalla-Duran, unpublished data).

Figure 1.

Holidays provide an opportunity for increased sexual mixing

Credit: KAREN ROBINSON/REX

Summary points

An increasing number of people are travelling abroad

Sex on holiday exposes an individual to different sexual networks

Screening for gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV should be performed if someone has had sex with a new partner while on holiday

Chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, and granuloma inguinale should be considered in addition if someone has had sex with someone from a developing country

Practitioners should be aware of the features of primary and secondary syphilis

A travel history should be taken, including the travel history of any partner

The alarming increase in the incidence of bacterial STIs and HIV in the United Kingdom11 as well as marked international variation in the prevalence of STIs worldwide, including more than 40 million people living with HIV,12 make any sexual encounter potentially hazardous. Young people aged 16-24 are at increased risk of STIs because of behavioural, socioeconomic, and biological factors and healthcare provision.2 The risk of STIs due to sexual intercourse on holiday is potentially increased through exposure to new sexual networks, the rate at which partners are changed while away, lack of condom use, and consumption of alcohol (an important cause of the modification of sexual behaviour).2 The prevalence of STIs in the community and core group that the new partner is from is a major determinant of risk. Susceptibility factors of the host also play a part—for example, lack of previous exposure to herpes simplex virus. Previous infection with gonorrhoea or chlamydia does not result in the production of protective antibodies, and reinfection with syphilis is possible. Neither are there any protective vaccines for STIs apart from hepatitis A and B.

Acute STIs

Travel abroad seems to be responsible for a small but increasingly important proportion of acute STIs in the United Kingdom. Of infectious syphilis infections in heterosexual men, 21% were from sexual contacts abroad,11 and 9% of people with gonorrhoea reported sex abroad in the preceding three months.13 Bisexual or homosexual men mainly reported sexual contact in mainland Europe (64%) or the United States (14%), whereas heterosexual men mostly reported sex in the Caribbean (35%) and the Far East (18%). Women mainly reported sex in the Caribbean (62%). In two London GUM clinics, 12% of STIs were due to sex abroad.14 Travellers to developing countries in particular are at increased risk of “tropical” infections, such as chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale (donovonosis), and syphilis, which has also become a major problem in the countries of the former Soviet bloc. Outbreaks of chancroid in the United States have been linked to people travelling abroad.15 Human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) is a virus that can be acquired through sexual transmission and is prevalent in the Caribbean and Japan.

HIV is a risk from sexual encounters at home or abroad, but risk of infection is increased in areas where prevalence is high, such as sub-Saharan Africa, the Far East, and, more recently, India, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Between 2000 and 2002, 69% of United Kingdom born men with heterosexually acquired HIV (235/342) were infected through sex while abroad, as were a quarter (75/316) of women. Of these men, 22% were probably infected in Thailand.11

Non-consensual sex

Another issue is that of non-consensual sex while on holiday. GUM clinics see women, but also men, who have been sexually assaulted while on holiday, particularly abroad. Confounding factors include use of alcohol, lack of knowledge of the locality, foreign tourists being perceived as easy prey, and increasingly the use of the date rape drug Rohypnol (personal observation, KER).

Sex tourism

The ultimate risk holiday is that of the sex tourist, where men or women travel long distances with the intention of having sex. Sex tourists tend to be from a slightly older group. A study of male German sex tourists in Thailand showed that most were aged 30-40 (range 20-76) and single, with a well paid job. Of these, 30-40% used condoms, and many did not consider their Thai contacts as prostitutes but as intimate friends, which resulted in reduced use of condoms.16 Their other destinations included the Philippines, Kenya, and Brazil. Half also had sexual contacts inside Germany, highlighting the risk of onward transmission when sex tourists return home.

Clinical signs of tropical STIs

As with “indigenous” STIs vaginal or urethral discharge or dysuria may occur. A genital ulcer is a common presentation for chancroid, particularly in men, and in 40% it will be associated with painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Women may have pain on defecation or dyspareunia. Donovonosis can result in ulcerative, granulomatous, or hypertrophic lesions. Lymphogranuloma venereum can present with an ulcer, but men more usually attend when they develop inguinal lymphadenopathy. Women may present with all these symptoms, but they may have only abdominal pain or back pain. Presentation may be up to six months after exposure and may be associated with systemic illness.

Syphilis can also present with a genital ulcer up to three months after exposure. Several months later, secondary syphilis may occur with systemic illness, skin rashes, alopecia, lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, and nephropathy. HIV may manifest as a glandular fever-like illness with seroconversion. HTLV-I may cause spastic paraparesis or leukaemia up to 20 years later.

Management of patients who have had new sexual partners on holiday

The management and treatment of people who have acquired, or are at risk of acquiring, an STI on holiday often require an intensive approach (box 1). Coinfection is a particular issue if they have had sex in an area with a high prevalence of STIs, and therefore a positive herpes culture from a genital ulcer should not obviate the need to consider and test for syphilis or chancroid as well. HIV testing should be in the context of informed consent, and this may be facilitated by the use of a leaflet to provide discussion before the test.17 National, evidence based guidelines for non-GUM specialists on obtaining informed consent have been published recently. HIV and syphilis testing should be done as a baseline test and then repeated six and 12 weeks after exposure (“the window period”). Hepatitis B testing should be performed at presentation and repeated at six months. Testing for hepatitis C should also be considered. If someone presents to their general practitioner within two weeks of risk behaviour with someone from an area where hepatitis B is endemic then an accelerated vaccine course may provide some protection. Exposure prophylaxis for HIV after sexual encounters is controversial18 but needs to be discussed if patients present soon after a high risk sexual exposure. Treatment, if given, should be with three antiretroviral drugs, starting ideally within one hour but at the most within 72 hours. Partner notification should be attempted if an STI is diagnosed, although this may be difficult and should take into account sexual partners since their return. Antibiotic treatment for gonorrhoea needs to take into account resistance patterns as infections from abroad often have reduced susceptibility to penicillin and ciprofloxacin.19

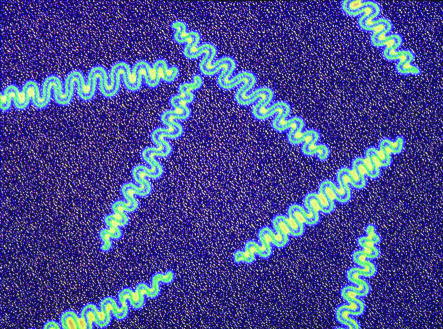

Figure 2.

A group of Treponema pallidum bacteria. These spirochaete bacteria cause syphilis in humans

Credit: ALFRED PASIEKA/SPL

Prevention

More widespread education is necessary for holiday-makers. Patients often visit their general practitioners or travel clinics for advice before travelling to exotic locations. This travel advice should include information on safer sex and the risks of sex abroad. Men travelling alone to Thailand and the Philippines on holiday are likely to be sex tourists and require advice on condom use and provision of hepatitis B vaccination. Others holidaying for longer periods, such as gap year students, should also be considered for vaccination. Information should be given that STIs are transmitted not only by vaginal and anal sexual intercourse but also by oral sex. If travelling to countries with a high HIV prevalence then both men and women should be informed of the need to consider post-exposure HIV prophylaxis if they have been sexually assaulted.18 Contraceptive needs should also be discussed.

Health advice in travel brochures was shown to be in a prominent position in only 11%, and only 3% were found to contain advice on safe sex.20 More worrying is tour operators' encouragement of sex with new partners by presenting prizes.10 As more holidays are booked through the internet, telephone, and teletext, providers of such services must look at ways of supplying advice on the risks of holiday sex (box 2). A need exists for more detailed data collection on STI acquisition while on holiday and assessment of interventions to reduce acquisition (box 3), particularly for people travelling to areas with a high prevalence of STI/HIV. Studies have shown that, although travellers are becoming more knowledgeable about STIs, this has little relation to their behaviour.21 Some evidence shows that men who do not use condoms at home do not use them abroad either.9 Publicity about the risk of sexual assault abroad is needed, combined with advice on how to reduce such a risk. Currently no single source is collecting or publishing such data, but information is available from various organisations, as shown in box 4. Articles in the popular press may be helpful in highlighting issues such as STI risk from sex abroad.22 Research needs to be multidisciplinary, considering the social context in which sex abroad occurs, and interventions require international cooperation.23

Box 1: Management of people who have had new sexual partners on holiday

Asymptomatic patients

Testing for gonorrhoea and chlamydia

Syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B serology testing at baseline, with repeats at six weeks, 12 weeks, and six months

Hepatitis B vaccination for people at risk if they present soon after last sexual intercourse, and for sex tourists

Consideration of post-exposure HIV prophylaxis within 48 hours of high risk sexual exposure

Prevention advice for future trips

Advice on sexual intercourse with regular or new partners while waiting for results

Symptomatic patients

Urgent referral to specialised STI services

Investigations for tropical STIs according to symptoms

HIV testing by polymerase chain reaction if an HIV seroconversion illness is suspected

Contact tracing for partners on holiday and in the United Kingdom

Box 2: Advice to travellers

Prevalence of STIs/HIV in area to be visited

Safer sex including condom use with any new partner

Risk of sexual assault

Dangers of “date rape” drug

Alcohol consumption advice

Information on post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV

Hepatitis B vaccination for sex tourists or those taking a prolonged holiday to high risk areas—for example, gap year students

Attendance at STI clinics if unprotected sexual intercourse occurs

Travel packs including condoms, drugs for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis

Box 3: Areas for research

Sexual behaviour of tourists

Interventions to promote safer sex for travellers

Value of routine screening for STIs after foreign travel

Database on sexual assault abroad

Box 4: Further sources of help and information

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH, www.bashh.org)—List of STI clinics in the United Kingdom; guidelines on testing and treatment

Foreign and Commonwealth Office (www.fco.gov.uk)—Information on how to avoid sexual assault and what to do if it occurs

Suzy Lamplugh Trust (www.suzylamplugh.org)—Handbook and video “Worldwise” on safety abroad

Department of Health (www.archive.official-documents.co.uk)—Health information for overseas travellers 2001 edition

Health Protection Agency (www.hpa.org.uk)—Information on STI rates in young people and international travellers

World Health Organization (www.who.int)—International STI and HIV epidemiology

Lonely Planet (www.lonelyplanet.org.uk)—Information provided by other travellers on dangers in various countries

Conclusion

Sexual encounters on holiday have the potential to be a major cause of morbidity, and the risk is likely to be greatest in young people and sex tourists. Studies have, however, been small scale and may therefore not be applicable to the general population. Preventive advice should be offered to all people going on holiday but particularly those going to the developing world, and vaccinations given as required. Young people should be encouraged to attend for sexual health screens after their holiday and secondary prophylaxis for hepatitis B and HIV considered. Traditional teaching at medical schools has been always to take a travel history in anyone with a fever. As can be seen from the diversity of presentations above, this advice should supplemented with the need always to take a sexual travel history from anyone with genital symptoms, rashes, hepatitis, glandular fever-like illness, or lymphadenopathy. This should include asking if any sexual partner has travelled abroad.

I thank George Kingdom for his helpful comments on the manuscript.

Competing interests: KER has received sponsorship to attend academic meetings from SmithKlineBeecham, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Boeringer.

References

- 1.O'Mahony C. Take a chance. Sex Transm Infect 2003;79: 261. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes KK, et al, eds. Sexually transmitted diseases. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999.

- 3.Department of Transport. Transport statistics: Great Britain, 1994. London: HMSO, 1994.

- 4.Wellings K, Macdowall W, Catchpole M, Goodrich J. Seasonal variations in sexual activity and their implications for sexual health promotion. J R Soc Med 1999;92: 60-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Transport. Transport statistics: Great Britain, 2003. London: HMSO, 2003.

- 6.Hawkes S, Hart GJ, Johnson AM, Shergold C, Ross E, Herbert KM, et al. Risk behaviour and HIV prevalence in international travellers. AIDS 1994;8: 247-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillies P. HIV related risk behaviour in UK holiday makers. AIDS 1992;6: 339-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finney H. Contraceptive use by medical students whilst on holiday. Fam Pract 2003;20: 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter S, Horn K, Hart G, Dunbar M, Scoular A, MacIntyre S. The sexual behaviour of international travellers at two Glasgow GUM clinics. Int J STD AIDS 1997;8: 336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batalla-Duran E, Oakeshott P, Hay P. Sun, sea and sex? Sexual behaviour of people on holiday in Tenerife. Fam Pract 2003;20: 493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Protection Agency. Renewing the focus. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom in 2002. London: HPA, November 2003.

- 12.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), World Health Organization. AIDS epidemic update: December 2003. Geneva: UNAIDS, WHO, 2003

- 13.Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme Steering Group. The gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials surveillance programme (GRASP) year 2002 report. London: Health Protection Agency 2003.

- 14.Hawkes S, Hart GJ, Bletsoe E, Shergold C, Johnson AM. Risk behaviour and STD acquisition in genitourinary medicine clinic attenders who have travelled. Genitour Med 1995;71: 351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmid GP, Sanders LL Jr, Blount JH, Alexander ER. Chancroid in the USA: re-establishment of an old disease ref. JAMA 1987;258: 3265-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleiber D, Wilke M. AIDS-bezogenes Risikoverhalten von (Sex-)Touristen in Thailand, in Zeiten von AIDS [AIDS related risk behaviour in (sex) tourists in Thailand, in the AIDS era]. In: Heckmann W, Koch MA, eds. Berlin: Sigma Rainer Bohn Verlag, 1994.

- 17.Rogstad K E, Bramham L, Lowbury R, Kinghorn GR. Use of a leaflet to replace verbal pre-test discussion for HIV: effects and acceptability. Sex Transm Infect 2003;79: 243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephenson J. PEP talk: treating non-occupational HIV exposure. JAMA 2003;289: 287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ison C A, Woodford P J, Madders H, Claydon L. Drift in susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Ciprofloxacin and emergence of therapeutic failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998;42: 2919-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shickle D, Nolan-Farrell MZ, Evans MR. Travel brochures need to carry better health advice. Comm Dis Public Health 1998;1: 41-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulhall B. Sex and travel: studies of sexual behaviour, disease and health promotion in international travellers—a global review. Int J STD AIDS 1996;7: 455-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.When are you most likely to catch an STI? Company 2003, November.

- 23.Hart GJ, Hawkes S. International travel and the social context of sexual risk. In: Carter S, Clift S, eds. Tourism and sex: culture, commerce and coercion. Cassell: London, 2000.