Abstract

Background

Good palliative care requires excellent interprofessional collaboration; however, working in interprofessional teams may be challenging and difficult.

Aim

The aim of the study is to understand the lived experience of spiritual counselors working with a new structured method in offering spiritual care to palliative patients in relation to a multidisciplinary health care team.

Design

Interpretive phenomenological analysis of in-depth interviews, was done using template analysis to structure the data. We included nine spiritual counselors who are trained in using the new structured method to provide spiritual care for advanced cancer patients.

Results

Although the spiritual counselors were experiencing struggles with structure and iPad, they were immediately willing to work with the new structured method as they expected the visibility and professionalization of their profession to improve. In this process, they experienced a need to adapt to a certain role while working with the new method and described how the identities of the profession were challenged.

Conclusions

There is a need to concretize, professionalize, and substantiate the work of spiritual counselors in a health care setting, to enhance visibility for patients and improve interprofessional collaboration with other health care workers. However, introducing new methods to spiritual counselors is not easy, as this may challenge or jeopardize their current professional identities. Therefore, we recommend to engage spiritual counselors early in processes of change to ensure that the core of who they are as professionals remains reflected in their work.

Keywords: Palliative care, Cancer, Spiritual care, Spiritual counselors, Interprofessional collaboration

Introduction

Good palliative care is aimed at improving the quality of life of patients by addressing physical, psychosocial, and existential or spiritual needs. It requires a multidisciplinary approach which requires excellent collaboration. Working in interprofessional teams, however, may be challenging and difficult [1]. Misconceptions or stereotypes can hamper a fruitful working relationship [2], and failures in interprofessional teamwork lead to compromised patient care [3, 4]. For interprofessional collaboration to be effective, shared mental models, enabling a common understanding of the situation, the plan for treatment, and the roles and tasks of the different health care professionals are needed [5]. A common understanding of one’s professional role requires a strong sense of professional identity: before others can understand your role, one must be aware of one’s own role and hence of one’s own identity [6–8].

For doctors and nurses, roles and identities may be self-evident, based on clearly defined protocols and evidence-based practice [9, 10]. However, this may not hold true for professionals addressing the spiritual domain of care. Often, care for spiritual needs is poorly articulated, and methods are hardly ever evidence-based [11]. Central to the professional identity of spiritual counselors is the competence of “listening carefully without agenda,” rather than conceptual or more structured approaches [12]. As a result, the role of a spiritual counselor in a palliative care setting may be unclear or ambiguous to the rest of the multidisciplinary team [13].

From a constructivist perspective, professional identity is considered to be an ongoing developmental process; it needs to be (re)created in the act of performing and in relation to others, being influenced by values, and expectations within the profession [14, 15]. Thus, spiritual counselors working in the field of palliative care need to negotiate different competing forces. For them, as members of the interprofessional care team, they have to accommodate a more structured approach and evidence base for their work as is required from other medical professionals as well [16]. However, following their current professional identity in which “being present” is a central goal, more than having structured conversations, this may be a challenge [12, 17, 18]. The aim of this current study was to explore how spiritual counselors learned to use a new, more structured, approach to the provision of spiritual counseling, as part of a randomized controlled trial [19]. Our research question was: how do spiritual counselors experience and give meaning to their experiences in learning to work with a structured model in offering spiritual care? We investigate the practice of spiritual counselors in hospitals to deepen our understanding of the professional roles and identities they bring to the interprofessional team. Therefore, the insights of this study will not only be helpful for the spiritual counselors themselves but also for all professionals working in interdisciplinary health care settings.

Methods

Context of the study

The current study is part of a larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) to examine the effect on quality of life of palliative cancer patients of an intervention consisting of two specific structured consultations led by a spiritual counselor [19]. Details of the professional intervention have been described elsewhere [20]. In brief, making use of an e-application, specifically designed for the purpose of this study and running on an iPad, the spiritual counselor asks a patient to draw a life line to indicate important life events on this line and formulate life goals. Then, the (dis)coherence between life events and life goals is explored in a structured way and discussed with the patient. Nine spiritual counselors were purposely selected for the RCT and were also invited to take part in the current study. All accepted the invitation. The selection was based on the following criteria: both men and women, with different religious backgrounds and with at least 5 years of work experience. The number of participating spiritual counselors was based on the calculated sample size of patients needed for the RCT (n = 153), of which half would be seen by a spiritual counselor [19]. To limit the workload for the spiritual counselors participating in the RCT while allowing for sufficient experience with the intervention, we decided to allocate a minimum of eight and a maximum of 10 patients to one spiritual counselor. Prior to the RCT, the spiritual counselors were trained in using the structured model with an e-application. The training period consisted of two plenary training sessions, supported by a written manual, and an individual pilot study. The pilot study consisted of two interviews in which the spiritual counselors were asked to use the model, first with a student and, thereafter, with a palliative cancer patient. The interviews conducted by the spiritual counselors during the pilot-study were recorded, transcribed, and examined. The research team evaluated the interviews separately with each spiritual counselor by giving oral and written feedback on a practical level e.g., “you can help the patient with the ipad when it is too hard” and on a more theoretical level e.g., “you could have asked here what do you mean with a good life?.” During the training period, one spiritual counselor quit the process because of a change of workload; yet, also, this spiritual counselor was interviewed for this qualitative study. After the training was finished and before the RCT was started, we carried out a single face-to-face interview with the spiritual counselors in which we addressed their experiences.

Research team

The first author (RK) interviewed the spiritual counselors. She already knew the spiritual counselors, as they all participated in the training that was part of the RCT. Within the whole research team, there was a broad range of expertise, both clinical (EH, HvL), spiritual (MSR, HS, HvL), educational (EH), and methodological (EH, MSR).

Phenomenological approach

In order to investigate and understand the experiences of the spiritual counselors, we used an interpretive phenomenological approach. The goal of phenomenology is to enlarge and deepen the understanding of the range of immediate experiences [21], and a phenomenologist tends to employ qualitative methods that put the experiences of the participants at focus [22]. In our study, we regard the lived experiences of the spiritual counselors as a phenomenon and used the interviews to enlarge and deepen our understanding.

Data collection

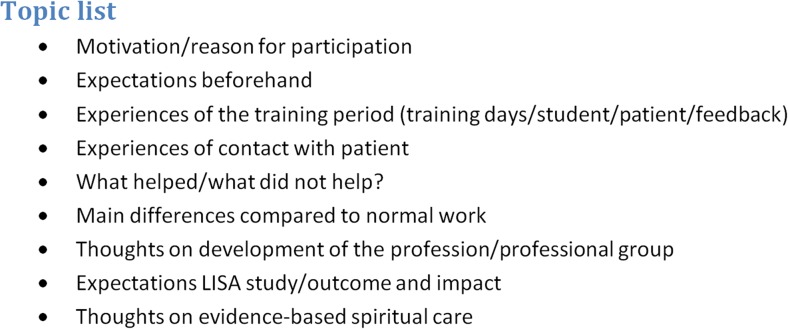

The interviews were conducted between November 2013 and January 2015 by one researcher (RK). Using a topic list (Fig. 1), we explicitly asked our participants to reflect on the new structured method in comparison to their usual work, asking for their motivation for participation in the RCT, their expectations and experiences in using the structured method and iPad application in the interaction with patients, and their thoughts about the development of the profession and evidence-based spiritual care. The interviews varied between 30 and 60 min and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Fig. 1.

Topic list

Analysis

We used template analysis to order the data and to discover the most important and recurring themes [23, 24]. A template consists of a list of codes and is organized in overarching themes. The codes and themes on the template are derived from the individual interviews. As a first step, two researchers (RK, EH) familiarized themselves with the data, by reading and rereading the transcripts. They identified units of meaning and labeled them with a summarizing code. After having coded the first three interviews, they started with the development of the template using sticky notes to group the codes and identify overarching themes. This template was revised and refined every time a new interview was coded, new codes were added, and other codes were combined. Adjustment and development of the template was regularly presented to a third researcher (HvL) to see if there was recognition, to make the main researchers aware of any biases and to deepen our understanding. Involving researchers with different backgrounds (medicine, educational sciences, and religious studies) was important to improve the breadth and depth of the analysis.

Following the constructivist paradigm, we did not look for coding disagreements. Within a constructivist research paradigm, knowledge and interpretations are considered to be constructed in the interaction between the interviewer and participants and between the researchers and the data. Therefore, the involvement of multiple coders was not intended to increase objectivity, but to reach a deeper understanding, building on different perspectives. In the process of making the template, we regularly presented adjustments to a third researcher (HvL). RK used a diary to note all personal findings while working on this article, we used this reflective research to record all the decisions we made regarding coding, the development of the template, and the final writing-up of the results.

Results

Participants

All spiritual counselors participating in the RCT [9] were willing to make time in order to take part in the interviews. The characteristics of the participating spiritual counselors are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. The age of the spiritual counselors ranged from 44 to 61 years. All but one had an academic training and were very familiar with the practice of providing spiritual care in a hospital setting (mean 12.5 years).

Table 1.

Respondent’s characteristics

| Gender | Age | Birth country | Work experience (hospital setting) | Clinical Pastoral Education | Religious background | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resp. 1 | Male | 55 | The Netherlands | 23 years | No | Humanist |

| Resp. 2 | Female | 44 | The Netherlands | 7 years | Yes | Roman Catholic |

| Resp. 3 | Female | 44 | South Africa | 8 years | Yes | Protestant |

| Resp. 4 | Male | 54 | The Netherlands | 18 years | Yes | Roman Catholic |

| Resp. 5 | Male | 61 | The Netherlands | 7 years | Yes | Roman Catholic |

| Resp. 6 | Female | 45 | The Netherlands | 8 years | No | Humanist |

| Resp. 7 | Male | 54 | The Netherlands | 21 years | Yes | Roman Catholic |

| Resp. 8 | Male | 58 | The Netherlands | 14 years | Yes | Roman Catholic |

| Resp. 9 | Female | 46 | The Netherlands | 6.5 years | No | Buddhist |

Table 2.

quotes

| Quote 1—resp. 1 | “What I find difficult is to be in a straitjacket of a model when it suddenly appears to be very constraining (…) but that is just my creative urge for freedom because I think there is more than this model, the patient is always more and I force her into a framework.” (resp.1) |

|---|---|

| Quote 2—resp. 4 | “It is valuable not to linger with the very first topic (…) but to carry on and really use the method, because eventually you will reach something good.(…) But I need to repress my first feelings, uh … I have a tendency to explore that what lies on top, things someone starts talking about.” (resp.4) |

| Quote 3—resp. 8 | “Well, if I am honest, I have not once really liked it, because there was always a kind of tension in me whether the technique would work.” (resp.8) |

| Quote 4—resp. 6 | “I first thought we are going to do interviews using such a nasty digital thing, that does not belong to my profession, and now I see that it is a very nice tool and also very helpful because you are sitting next to each other, bending over it together.” (resp.6) |

| Quote 5—resp. 4 | “Then it doesn’t all play in my head, but it is, it kind of becomes externalized. Yes, and also it keeps my head together, because otherwise I swerve off topic. (…) I was also afraid that the fact that the device is out there would work alienating, but I manage to continue a dialogue with the patient and to use the device just as a tool.” (resp.4) |

| Quote 6—resp. 6 | “It has to do with my education, that we really learned not to be directive (…) but instead connect with the story of the other who sets the agenda and I do not have a clear agenda. So I need to make a switch I am not sitting here as spiritual counselor giving support, but I am doing this in the context of a research project.” (resp.6) |

| Quote 7—resp. 2 | “The patient should be leading and determining what we are talking about. And occasionally I ask a question, but, well, the patient decides whether or not to talk about it and where we are going.(…) When I have a conversation with a patient and, at one point, the conversation falls silent, because the patient is just sitting there, having internal conversations, (…) I am perfectly satisfied! (…) I've done my job. But now I have to do everything. I have to pull out everything, everything must be explicitly stated.” (resp.2) |

| Quote 8—resp. 3 | “The ‘researcher hat’ is actually needed to facilitate the discussion, to adhere to the model.” (resp.3) |

| Quote 9—resp. 5 | “I think the difficulty for me is, but that is very personal, that I need to get the right mindset, that I have to prepare well, and know, ok now I am working with this, that is your tool and these are the rules, these are the frames and within this you can move. But that is a matter of practice.(…) I should be aware that the patient does not run off with a story and takes control.” (resp.5) |

| Quote 10–resp. 2 | “The core of my profession is (…) to help people to enter into dialogue with themselves or listen to themselves, (…) around the themes that are important, when they are falling ill, that you help them to get close to what is important to them, what has meaning, what carries them and gives strength.”(resp.2) |

| Quote 11—resp. 5 | “You do see that a shift occurs (…) out there they transferred the spiritual care into the department of occupational therapy. (…) a very odd move that you entitle spiritual care as an activity that anyone could perform.” (resp.5) |

| Quote 12—resp. 9 | “You can highlight the sanctuary position as something that is unique to you or your profession (…). We must indeed continue to do so, but that does not mean that you should not do other things. (…) Not clinging (…) Then you take on a defensive mode of ‘you take everything from us, but we are very unique in it!’ (…) I do think this is changing. (…) Many young spiritual counselors (…) are very open-minded to this. (…) They also combine the other parts. The science part is not dirty or anything. It is no blaspheme to make things evidence-based. There is nothing wrong with that.” (resp.9) |

| Quote 13—resp. 3 | “The added value [of the RCT] is that you show to the oncologists (…) here is an example, this is what it looks like and this is what it contributes, making it visible.” (resp.3) |

| Quote 14—resp. 7 | “Chaplains are not trained for that. They come from very strong internally oriented worlds.” (resp.7) |

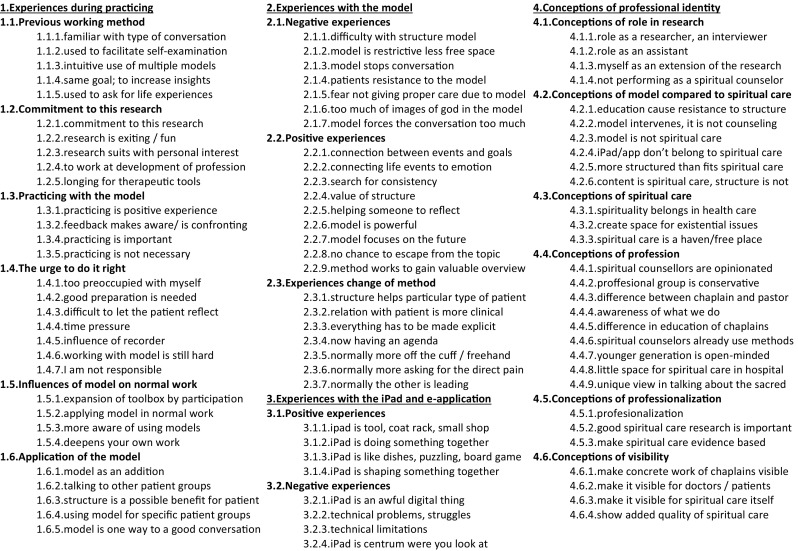

Template

From the interview data, we designed a template (Fig. 2). The template shows two overarching themes: negotiating experiences (1, 2, 3) and conceptions of professional identity (4). Negotiating experiences relates to experiences during training and practicing (first heading of the template), experiences with the new, structured model (heading 2), and experiences while working with the iPad and e-application (heading 3). The fourth heading in the template includes experiences with developing a new professional identity. In this study, we were interested in how spiritual counselors experience and give meaning to their experiences while learning to work with a new, structured model in offering spiritual care and how this influences identity development. As the first heading of the template is mostly capturing practical experiences during training, in the description of our results, we will focus on headings two, three, and four of the template. First, we will discuss the experiences of the spiritual counselors with the model. Second, we will address the experiences with the iPad and e-application and finally we present our findings regarding the spiritual counselors’ conceptions on their profession and professional identity.

Fig. 2.

Template showing two overarching themes

Experiences with a new method: struggles with structure

The participating spiritual counselors all reported both positive and negative experiences with the model. Most importantly, they were struggling with the need to follow the fixed structure of the model. They reported that the model was too decisive and that it sometimes hampered the conversation, which led to a resistance against the predefined structure. Some were even afraid of not being able to give good care to the patient, when adhering to the model, ultimately leading to refraining from responsibility. The model was associated with wearing a straightjacket. (Quote 1) All counselors also reported positive experiences with the model. They discovered the value of the model in addressing life events and emotions, the search for consistency and focusing on the future. Even the structure of the model was eventually appreciated. According to the spiritual counselors, the value of the structure was that it helps patients to reflect and that there is no opportunity to escape from the topic. They stated that this may be of particular help to a specific type of patient, for instance, patients who do not normally express themselves easily. Some spiritual counselors mentioned that the model requires to make everything explicit while in ordinary conversations things can remain implicit. The relationship with the patient was experienced as different from the normal situation, due to the setting of this study design. Some reported that the relationship was more clinical, and the patients were entering the room with a clear goal, to participate in a scientific study. Spiritual counselors referred to setting the agenda and leading the patients in a very structured way as a completely new approach. (Quote 2)

Experiences with a new method: the influence of an iPad

Using an e-application that runs on an iPad is also completely different from the normal work setting of hospital spiritual counselors. In the beginning of the training, almost all counselors struggled with the use of the iPad. (Quote 3) They talked about the iPad in strong terms such as “it is an awful digital thing,” and they experienced technical problems related to the iPad. Some counselors emphasized that the iPad does not belong to spiritual care in general. Once the spiritual counselors got more acquainted with the iPad and there were less technical problems, they all mentioned positive perceptions too (Quote 4). Experiences with the iPad were often reported in terms of metaphors, maybe to describe the special role of the iPad that cannot easily be explained in normal words, using phrases such as “the iPad is a tool, a coat rack, a small shop.” One counselor reported that working with the iPad had the same effect as when a patient is showing photos. He experienced it as helpful to look at something together instead of looking at each other. Others reported on the new dimension that came along by working with an iPad: “the iPad is doing something together, like doing the dishes, puzzling or playing a board game.” Another dimension that emerged was the effect of visualizing part of the conversation, which many counselors described as helpful in staying focused. (Quote 5)

Conceptions on professional identity: adapting to a certain role

Almost all spiritual counselors reported that in order to conduct these structured conversations they intentionally changed roles, from acting as a counselor into being a researcher, an interviewer or a research assistant. (Quote 6) They referred to their previous education, in which they had learned what a spiritual counselor should be like, which is different from the requirements of this study. (Quote 7) From not having an agenda to completely leading the patient is a big shift and requires behavioral changes. One way of dealing with this different way of performing their work was deliberately changing roles or wearing different “hats.” (Quote 8) Working with the model requires a specific mindset. (Quote 9)

Conceptions of professional identity: changing identities of the profession

Some spiritual counselors explicitly reported that this model is beyond ordinary spiritual care because it is too structured, leading to the question what exactly entails spiritual care in the context of health care. (Quote 10) Spiritual counselors mentioned that this notion on the core of spiritual care is currently changing, as are the views on the position of spiritual care within the hospital infrastructure. Furthermore, the financial constraints health care in general is facing also stimulate counselors to rethink about their profession. (Quote 11) All spiritual counselors emphasized that spiritual care is an important part of health care, which certainly belongs there. Spiritual care is seen as creating space for existential issues and may serve as a safe haven, a free place, especially compared to doctors, who usually have limited time and attention for patients. How to emphasize this unique position seemed to be a matter of debate. (Quote 12) There is at this moment very little research done on the effects of spiritual care, while the professional background of hospital spiritual counselors is academic. (Quote 13) Spiritual counselors, however, have difficulties with making their work visible. (Quote 14) All counselors emphasized the importance of visibility, underpinning, and professionalization of their work, as one of the main reasons to participate in the RCT, illustrating how the identity of the profession is changing.

Discussion

Statement of main results

The objectives of our study were to understand how spiritual counselors experienced working with a structured method in offering spiritual care and to discover how they gave meaning to their experiences. Central to their accounts was the experience of their professional identities being challenged. Using the structured method leads to both negative and positive experiences. Negative experiences with the model were related to its highly structured way of relating with patients, which sometimes hampered the interactions with patients, and therefore, could be experienced as too constraining. Positive experiences also pertained to the structure, now facilitating the conversation with patients who do not easily reflect on their feelings and providing a tool to focus on core topics. Although initially perceived as an awful digital thing, the iPad finally was also accepted as a helpful tool, enhancing different ways of interacting with patients. Despite their positive experiences, all spiritual counselors referred to their professional identities as being at stake. Many spiritual counselors reported that they needed to intentionally change their roles, from being a counselor into acting as a researcher, raising the question what the core of being a spiritual counselor implies. All spiritual counselors reported on the importance of visibility, underpinning, and professionalization of their work.

Strengths and limitations of this study

All the interviews were conducted by one researcher (RK) who was also responsible for designing the training period and for providing support and feedback. An advantage of this study design was that RK had already a relationship with the participants and knew the context, so the spiritual counselors could immediately report their experiences without the need for further explanation. A disadvantage may be that the researcher was too much biased or that the spiritual counselors gave socially acceptable answers. However, in the interviews, the spiritual counselors did report a substantial amount of negative feelings, experiences, and views. To develop a broad understanding, the interview study was mainly conducted in collaboration with another researcher (EH) who was not part of the project before and had no previous contact with counselors. This enabled EH to have an external look at the study and study results. The wide range of expertise within the research team could be regarded as a strength enriching our analysis. Our study findings may be limited by the large homogeneity of our sample. Most of our participants had a Roman Catholic background, were white, middle-aged, and Dutch. It could be that colleagues who are younger, with other religious backgrounds, and working in other parts of the world would have had different experiences. Younger spiritual counselors for instance might have experienced less struggles with technique and structure because they are less rooted in their profession. The inclusion of mostly Dutch spiritual counselors also influenced the outcomes, as the issues of visibility and professionalism could be less relevant in countries where spiritual counselors are still sent from the church. Nevertheless, insights of this study could be of substantial value when spiritual care is shifting towards a more integral part of health care, as this shift is noticed in different countries [25–27].

Interpretation of findings in relation to other studies

Other studies show that the profession of spiritual care is in transformation, evolving from a denominationally bound profession into a specific kind of healthcare profession [28]. These developments ask for more validity, evidence, professionalization, and collaboration in the profession of spiritual care [16, 25]. While our research question focussed on the lived experiences of the spiritual counselors in working with a new structured method, as a result, we identified struggles with professional roles and the identity of the profession. This finding may have to do with the fact that spiritual counseling is a relatively young profession in a changing environment. Previously, spiritual counselors were sent by the church, while in our sample, all were employed by the hospital. Many spiritual counselors oppose a more structured way of working because standards seem to conflict with their sanctuary position as well as with the concept of “presence” in client-centered therapy [29]. This concept from Rogers has profoundly influenced the development of spiritual counselling and underscored the value of just being present as a spiritual counselor and not intervening too much [30]. By using this new structured method, spiritual counselors were forced into an “action mode” by having to lead the patient through the questions [31]. A shift from the mode of “being present” to an “action mode” could be an additional explanation for the struggles the spiritual counselors experienced.

Meaning of this study: implications and future research

Within the biopsychosocial paradigm, existential or spiritual needs may receive little attention, and non-medical input in interprofessional team discussions tends to be undervalued by medically educated team members [32, 33]. This issue becomes even more pressing in palliative care, when in the face of death, the relevance of the search for meaning and purpose in life is intensified [34]. Policymakers should be aware of the important role spiritual counselors can play in the palliative care setting, but also consider their professional identity when introducing new methods for delivering spiritual care. Spiritual interventions can have a complex nature and sometimes special clinical training is necessary to engage in them. An appropriate recommendation is therefore that these interventions should be done only by a board-certified chaplain or an equivalently prepared spiritual care provider [35]. When a change in work content offers a threat to the professional role, professionals will not readily adapt to the new routines, which could reduce the effectiveness of interprofessional teams [36]. Therefore, in processes of change, attention should not only be paid to an explanation and teaching of practical methods but also to the role and position of a spiritual counselor. It would be helpful to engage spiritual counselors early in the processes of change. Future research should focus on the effect that increased visibility of spiritual counselors in palliative teams may have on the professional identity of other team members and which may ultimately contribute to delivering better quality palliative care.

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by KWF, the Dutch Cancer Society/Alpe du’HuZes, and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies.

Contributors

The study was designed by RK, EH, and HvL. Data collection was carried out by RK. RK and EH designed data collection tools and coded the interviews, with intellectual input of HvL. RK and EH wrote the first draft and discussed it with HvL, MS, and HS. All the authors contributed to the subsequent drafts and reviewed the final draft. All authors had access to the original data. All the authors approve this document, and RK is the guarantor.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval was not obtained for this particular interview study.

Transparency declaration

RK affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Funding

This study is funded by The Dutch Cancer Society/Alpe d’HuZes and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. Both companies had no role in the design, management, data collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data or in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests

We have read and understood the Springer on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: Dr. Scherer-Rath, dr. Helmich, Dr. Schilderman, and Mrs. Kruizinga have nothing to disclose. Dr. van Laarhoven reports grants from the Dutch Cancer Society and Janssen Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of the study.

Data sharing

Interview data and diary notes available can be obtained from the corresponding author (in Dutch). Participants gave informed consent for anonymous data sharing.

References

- 1.O’Connor M, Fisher C. Exploring the dynamics of interdisciplinary palliative care teams in providing psychosocial care:“Everybody thinks that everybody can do it and they can’t”. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:191–196. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwood F. The ambivalent chaplain: negotiating structural and ideological difference on the margins of modern-day hospital medicine. Med Anthropol. 2006;25:1–29. doi: 10.1080/01459740500488502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:186–194. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez G, Coiera E. Interdisciplinary communication: an uncharted source of medical error? J Crit Care. 2006;21:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:149–154. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattessich PW, Monsey BR, Collaboration: What makes it work . A review of research literature on factors influencing successful collaboration. Saint Paul: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation; 1992. p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor M, Fisher C, Guilfoyle A. Interdisciplinary teams in palliative care: a critical reflection. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2006;12:132–137. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.3.20698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronstein LR. A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc Work. 2003;48:297–306. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou P, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach ebm. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daaleman TP, Usher BM, Williams SW, et al. An exploratory study of spiritual care at the end of life. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:406–411. doi: 10.1370/afm.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baart A. The fragile power of listening. Suid-Afrika: Practical Theology in South Africa = Praktiese Teologie; 2003. pp. 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett D (2013) What do chaplains do? Health and social care chaplaincy. pp 36–40

- 14.King N, Ross A. Professional identities and interprofessional relations: evaluation of collaborative community schemes. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;38:51–72. doi: 10.1300/J010v38n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheer JW, Catina A. Empirical constructivism in Europe. Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag; 1993. p. 287. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Geer J, Leget C. How spirituality is integrated system-wide in the Netherlands palliative care national programme. Progr Palliat Care. 2012;20:98–105. doi: 10.1179/1743291X12Y.0000000008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schilderman J. Religion as a profession (empirical studies in theology 12) Leiden: Brill; 2005. p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smeets W. Spiritual care in a hospital setting. An empirical-theological exploration. J Empir Theol. 2008;21:145–146. doi: 10.1163/157092508X297582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruizinga R, Scherer-Rath M, Schilderman JB, et al. The life in sight application study (lisa): design of a randomized controlled trial to assess the role of an assisted structured reflection on life events and ultimate life goals to improve quality of life of cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:360. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganzevoort RR, de Haardt M, Scherer-Rath M. Religious stories we live by: narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. Leiden: Brill; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegelberg H, Schuhmann K. The phenomenological movement: a historical introduction. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1960. p. 768. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulding C. Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: a comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research. Eur J Mark. 2005;39:294–308. doi: 10.1108/03090560510581782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King N (2012) Doing template analysis. Qualitative organizational research: core methods and current challenges, pp 426–250

- 24.Brooks J, King N (2012) Qualitative psychology in the real world: the utility of template analysis. Presented at paper presented at British psychological society annual conference

- 25.Urs Winter-Pfändler CM (2010) Rolle und Aufgaben der Krankenhausseelsorge in den Augen von Stationsleitungen. Eine Untersuchung in der Deutschschweiz. Wege zum Menschen 585–597

- 26.Karle I. Sinnlosigkeit aushalten! Ein Plädoyer gegen die Spiritualisierung von Krankheit. Wege zum Menschen. 2009;61:19–34. doi: 10.13109/weme.2009.61.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munich L (2010) First professorship for spiritual care will be filled in an ecumenical spirit. LMU. Available at https://www.en.uni-muenchen.de/news/newsarchiv/2010/2010-spiritualcare.html. Accessed 19 March 2014, 2015

- 28.Smeets W, Morice-Calkhoven T. From ministry towards spiritual competence. Changing perspectives in spiritual care in the netherlands. J Empir Theol. 2014;27:103–129. doi: 10.1163/15709256-12341291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackor AR. Standardization of spiritual care in healthcare facilities in the Netherlands: blessing or curse? Ethics Soc Welf. 2009;3:215–228. doi: 10.1080/17496530902951996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodley BT. Personal presence in client-centered therapy. Pers Cent J. 2000;7:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitehead PR (2012) The lived experience of physicians dealing with patient death. BMJ supportive & palliative care. bmjspcare-2012-000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Payne S, Haines R. The contribution of psychologists to specialist palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2002;8:401–406. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2002.8.8.10684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams F, Kirkman-Liff B, Netting F (1999) Lessons learned across sites. Enhanc Prim Care Elder People 219–234

- 34.Best M, Aldridge L, Butow P et al (2014) Assessment of spiritual suffering in the cancer context: a systematic literature review. Palliative Supportive Care 1–27 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell RJ, Parker V, Giles M. When do interprofessional teams succeed? Investigating the moderating roles of team and professional identity in interprofessional effectiveness. Hum Relat. 2011;64:1321–1343. doi: 10.1177/0018726711416872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]