1. Introduction

It has been hypothesized recently that emotional processes are associated with childhood stuttering (Conture & Walden, 2012; Conture, Walden, Arnold, Graham, Hartfield & Karrass, 2006). During the same time frame, findings from several empirical studies of the association between emotional processes and childhood stuttering appear to support this hypothesis (Anderson, Pellowski, Conture & Kelly, 2003; Arnold, Conture, Key & Walden, 2011; Eggers, De Nil, & van den Bergh, 2009, 2010; Embrechts, Ebben, Franke, and van de Poel, 2000; Johnson, Walden, Conture & Karrass, 2010; Karrass, Walden, Conture, Graham, Arnold, Hartfield et al., 2006; Schwenk, Conture & Walden, 2007; Kazenski, Guitar, McCauley, Falls, & Dutko, 2014; Walden, Frankel, Buhr, Johnson, Conture & Karrass, 2012). Although none of these findings prove that emotion causes stuttering, it does suggest that emotion is associated with stuttering and that the nature of this association warrants further empirical study.

To date, empirical study of the association between emotion and childhood stuttering has involved three different methods: (1) caregiver reports or questionnaires (e.g., Anderson et al., 2003) (2) coded behavioral observation (e.g., Walden et al., 2012), and (3) psychophysiology (e.g., Arnold et al., 2011). In the brief literature review to follow, findings from each methodological approach will be presented to provide context for the present empirical study.

Caregiver reports have been frequently used to empirically study the association between emotion and childhood stuttering (e.g., Anderson et al., 2003; Embrechts et al., 2000; Eggers et al., 2010; Felsenfeld, van Beijsterveldt, Boomsma, 2010; Karrass et al., 2006). Although some (Kagan, 1998; Strelau, 1983) have questioned the accuracy of parent reports and suggested that parents are biased informants, others (e.g., Henderson & Wachs, 2007) have suggested that “While parent report measures do contain some subjective parental components, available evidence indicates that these measures also contain a substantial objective component that does accurately assess children’s individual characteristics” (p. 402). Such pro and con opinions aside, several empirical studies based on parent report have shown that children who stutter (CWS), when compared to children who do not stutter (CWNS), exhibit significantly (a) lower ability to adapt or adjust to novelty and change (e.g., the ease and ability of a child to change his/her routine) (Anderson et al., 2003), (b) more emotionality (e.g., “crying intensely when hurt”) (Karrass et al., 2006), as well as lower emotion regulation (e.g., “adjusting easily to changes in routine”) (Karrass et al., 2006), (c) less success in adapting to new environments (Embrechts et al., 2000), (d) lower inhibitory control and attention shifting, but higher negative affect such as anger and frustration as reported by caregivers (Eggers et al., 2010), and (e) more attentional problems at ages 5 and 7 years of age (Felsenfeld et al., 2010). Noting the salience of attention to emotion, Rothbart (2011) states that, “Attention and emotion systems influence each other, with attention selecting or avoiding information about emotion, and emotion affecting how easily we can shift or focus our attention” (p. 76).

Coded behavioral observations have also been used to assess the association between emotion and childhood stuttering (Johnson et al., 2010; Jones, Conture, Walden, 2014a; Ntourou, Conture & Walden, 2013; Schwenk et al., 2007; Walden et al., 2012). Such behavioral observations include coding for behavioral signs of positive and negative affect (e.g., Jones et al., 2014a, Walden et al., 2012), expressive nonverbal positive (e.g., smiling) or negative behaviors (e.g., frowning, groaning) (Johnson et al., 2010), and shifts in attention (e.g., frequency and duration of looks away from or to a stimulus as in Schwenk et al., 2007). Results of these studies indicate that CWS, when compared to CWNS, exhibited (a) less habituation of attention to irrelevant background stimuli (Schwenk et al., 2007), (b) more negative emotional expression upon receiving an undesired gift (Johnson et al., 2010), (c) greater tendency to exhibit emotionally reactive behaviors prior to and during stuttered utterances than fluent utterances (Jones et al., 2014a), (d) greater stuttering with greater negative emotion during speaking, and less stuttering when negative emotion is accompanied by greater emotion regulation (Walden et al., 2012) and (e) more self-speech and negative emotional behaviors during an emotionally frustrating task (Ntourou et al., 2013).

Psychophysiological methods have also been used to study the relation of emotion to stuttering. To date, most psychophysiological studies of stuttering have involved adults who stutter (for review, see Bloodstein & Ratner, 2008). More recently, however, some have employed various psychophysiological methods to study emotion in young children who stutter (Arnold et al., 2011; Jones, Buhr, Conture, Tumanova, Walden and Porges, 2014b; Ortega & Ambrose, 2011; van der Merwe, Robb, Lewis & Osmond, 2011). Findings have shown that compared to CWNS, CWS exhibit (1) no significant between-group differences in EEG frontal asymmetries while children listened to neutral, happy and angry background conversations (Arnold et al, 2011); (2) less vagal (parasympathetic) activity, indicating less emotion regulation during baseline (i.e., neutral) video-viewing condition (Jones et al., 2014b); (3) significantly lower overall salivary cortisol levels (relative to published norms) at two of three sampling occasions measured over three consecutive days (Ortega & Ambrose, 2011); and (4) no significant differences in salivary cortisol across three sampling situations (i.e., baseline, pre- and post-conversation) (van der Merwe et al., 2011)1.

Clearly, these studies—whether employing parent reports, coded behavior observations or psychophysiological measures- have made significant contributions to our understanding of the association between emotion and childhood stuttering. However, at present, there is a need to determine specific activity of young children’s autonomic nervous system (ANS) and its association with childhood stuttering. For example, activity of the sympathetic branch of the ANS, a branch of the ANS considered to be particularly salient to emotional arousal.

In brief, the ANS mainly regulates an individual’s internal environment in attempting to maintain bodily homeostasis or equilibrium, often in response to environmental challenges. This is accomplished by facilitating adaptive responses of the endocrine, immune, sensory-motor and cognitive systems to physical or psychological challenges (Dawson, Schell, & Filion, 2007; Porges, 2007). In addition to its crucial role of maintaining brain and body homeostasis, ANS supports complex behaviors such as emotion, decision-making, and motivation (e.g., Dawson et al., 2007; Gross, 1998; Porges, 2007). It has been well documented that the ANS activity distinguishes between positive and negative emotions, with negative emotions associated with greater ANS activity than positive emotions (e.g., Cacioppo, Berntson, Klein, & Poehlmann, 1997; Ekman, Levenson & Friesen, 1983; Kreibig, 2010; Sequeira, Hot, Silvert & Delplanque, 2009).

Of the various relatively direct measures of ANS physiological reactivity, electrodermal activity (EDA) has been demonstrated to be a reliable index of arousal in response to emotional stimuli (e.g., Sequeira et al., 2009). EDA2 measures changes in skin conductance, which are associated with changes in sweating in eccrine glands, which are related to activation in the sympathetic branch of the ANS (Handler, Nelson, Krapohl & Honts, 2010). Thus, because ANS appears to play a salient role in emotional processes and motivation, skin conductance measures have been widely used to study psychological processes. Furthermore, the relatively high temporal resolution of EDA enables reliable, robust recordings of changes in electrical properties of the skin in relation to concurrent processes that occur within a fairly brief time frame.

Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Speech Production

Speech-language production is a highly complex task (see Levelt, Roelofs, & Meyer, 1999, for one theory of speech-language production that attempts to account for such complexity), requiring coordination of many neural systems involved in linguistic encoding, motor control, cognition, and emotion. Speaking has been associated with increased autonomic arousal in adults (e.g., Het, Rohleder, Schoofs, Kirschbaum & Wolf, 2009; Weber & Smith, 1990; and Peters & Hulstjin, 1984). Specific to speech disfluencies, Weber & Smith (1990) reported that high sympathetic arousal was associated with occurrence and severity of disfluencies. Kleinow & Smith (2007) empirically studied the potential interactions among linguistic, motor and autonomic factors (i.e., heart rate, skin conductance, finger pulse volume) associated with children and adults’ speech production and reported that high autonomic arousal affected speech motor coordination in both age groups. Interestingly, they found that children, when compared to adults, exhibited greater autonomic arousal as well as greater variability in their speech motor coordination, activity apparently associated with a less mature cognitive and linguistic system. Similarly, in a recent study of autonomic arousal of children and adults in speech and non-speech tasks, Arnold, MacPherson, & Smith (2014) reported that both children and adults demonstrated higher arousal for speech than non-speech tasks. In addition, Arnold et al. (2014) found gender differences in children’s ANS activity during speaking tasks (i.e., higher arousal in boys than girls during a complex narrative task), a finding attributed to gender differences in speech and language skills.

Overall, the interaction among emotional processes and linguistic, cognitive and motor factors in speech-language production, especially in children, has been relatively understudied. Therefore, the exact nature of the mechanisms underlying the influence of autonomic activity on speech largely remains unknown. However, current evidence suggests that linguistic, cognitive, emotional and motor factors influence each other, and that autonomic activity, particularly arousal, impacts speech-language production (Arnold et al., 2014; Kleinow & Smith, 2006; Weber & Smith, 1990). Heightened autonomic arousal (i.e., greater emotional reactivity) during speaking may be problematic, for example, arousal may divert the speaker’s attentional resources from concurrent speech-language planning and production, increasing the likelihood of subtle to not so subtle breakdowns or disruptions in speech-language.

Skin Conductance and Stuttering

In the last approximately 60 years, based on the present authors’ review of the literature, there have been 12 published empirical studies of the association between skin conductance and stuttering (Adams & Moore, 1972; Berlinsky, 1954; Brutten, 1963; Dietrich & Roaman, 2001; Gray & Brutten, 1965; Gray & Karmen, 1967; Guntupalli, Everhart, Kalinowski, Nanjundeswaran, Saltuklaroglu, 2007; Kraaimaat, Janssen, Brutten, 1988; Jones et al., 2014b; Peters & Hulstjin, 1984; Reed & Lingwall, 1976, 1980; Weber & Smith, 1990). Eleven of these studies involved adults or adolescents who stutter (AWS), with only one, that present authors are aware of, that involved preschool-age children who stutter (Jones et al., 2014b).

Results of these 12 studies have lead to mixed findings including: (1) no significant between-group differences in skin conductance level (SCL) between AWS and AWNS (Gray & Karmen, 1967; Peters & Hulstjin, 1984, Weber & Smith, 1990; Zhang, Kalinowski, Saltuklaroglu, Hudock, 2010), (2) significant between-group differences in SCL, with AWS exhibiting significantly higher SCL than AWNS during anxiety-inducing conditions (Berlinsky, 1954), (3) significant within-group differences in SCL for AWS in different task conditions such as speaking, listening, viewing (Adams & Moore, 1972; Brutten, 1963; Gray & Karmen, 1967; Jones et al., 2014b; Kraaimaat et al., 1988; Peters & Hulstjin, 1984; Reed & Lingwall; 1976, 1980; Weber & Smith, 1990) and (4) no significant within-group differences in SCL for AWS in different task conditions such as speaking, listening, reading, viewing (Dietrich & Roaman, 2001; Gray & Brutten, 1965). Given between-study differences in sample size, gender, tasks and methods for collecting SCL, it is hard to generalize the above findings. However, further empirical study with modern data collection and analysis methods and greater numbers of participants, should help better assess between-group differences in SCL in people who do and do not stutter.

The single empirical study of SCL of preschool-age CWS and CWNS by Jones et al. (2014b) assessed children’s emotional reactivity and emotion regulation by measuring SCL – associated with sympathetic activity - and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) – associated with parasympathetic activity. These measures were obtained during video-viewing of emotionally valanced (i.e., neutral, positive and negative) age-appropriate video clips as well as a subsequent speaking (i.e., narrating stories) task. They reported that CWS, when compared to CWNS, exhibited higher SCL values during a positive listening-viewing condition as well as higher SCL values during speaking conditions that followed viewing of positive video clips. There were no significant between-group differences in SCL values during speaking conditions that followed negative or neutral video viewing conditions (Jones et al., 2014b).

Thus, present understanding of the association between emotion and childhood stuttering is mainly based on caregiver reports or coded behavioral observations of children’s emotion, with minimal empirical study of this association based on psychophysiological measures. This leaves open the question of whether all aspects of emotion, covert (e.g., autonomic) as well as overt (i.e., behavioral), are associated with childhood stuttering. Therefore, we presently lack a comprehensive understanding of the association between emotion and stuttering in children.

To address this gap in knowledge, the current study assessed sympathetic arousal (i.e., a psychophysiological associate of emotional reactivity) during a picture-naming task in which young CWS and CWNS were instructed to name pictures under conditions of temporal, communicative and interpersonal stress.

This investigation addressed four specific issues. First, the study investigated whether for all participants in the study (i.e., young CWS + CWNS) there were between-condition differences in sympathetic arousal as measured by SCL. It was hypothesized that both CWS and CWNS would exhibit higher overall SCL during the speeded picture-naming task than during a pre-task and a post-task baseline. Second, the study assessed between-group differences in SCL during the pre-task baseline. It was hypothesized that CWS’s overall pre-task baseline SCL would differ from their CWNS peers. Third, the study investigated between-group differences in SCL during a stress-inducing task. It was hypothesized that CWS’s overall level of sympathetic arousal during the task would differ from CWNS. Fourth, the study assessed between-group differences in post-task baseline SCL. It was hypothesized that CWS’s overall SCL during the post-task baseline would differ from CWNS. Due to the limited nature of the quantity and quality of evidence regarding the association between childhood stuttering and autonomic correlates of emotion, the hypotheses proposed are exploratory, rather than explicit statements predicting directionality of effect (see Conture, Kelly, Walden (2013) for further considerations and possible directionality of effects).

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants included 37 CWS (9 female) and 39 CWNS (10 female) between the ages of 36 and 71 months. CWS’ chronological age (M = 50.71, SD = 9.78) was not significantly different from that of CWNS (M = 53.14, SD = 9.59) t(72) = 1.079, p = .284.

Data were collected as part of a large-scale investigation of linguistic and emotional contributors to developmental stuttering (e.g., Arnold et al., 2011; Choi, Conture, Walden, Lambert & Tumanova, 2013; Johnson et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2014b, Walden et al., 2012) conducted by Vanderbilt University’s Developmental Stuttering Project. All participants were monolingual English speakers. Participants were paid volunteers whose parents learned of the study from advertisements in a free, local monthly parent magazine in Middle Tennessee, were contacted from Tennessee state birth records, or were referred to the Vanderbilt Bill Wilkerson Hearing and Speech Center for an evaluation. The study’s protocol was approved by Vanderbilt University’s Institutional Review Board, and for all participants informed consent by parents and assent by children were obtained.

2.2 Classification and Inclusion Criteria

To reduce the possibility of confounds with clinically significant speech-language and hearing concerns, participants’ articulation, receptive and expressive language skills, as well as hearing abilities, were assessed using standardized measures. Specifically, the “Sounds in Words” subtest of the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation-2 (GFTA-2; Goldman & Fristoe, 2000) measured articulation; the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Third Edition (PPVT-IV Dunn & Dunn, 2007) assessed receptive vocabulary; the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT; Williams, 1997) evaluated expressive vocabulary; and the Test of Early Language Development-3 (TELD-3; Hresko, Reid, & Hamill, 1999) measured receptive and expressive language abilities. Children who scored below the 16th percentile (i.e., approximately one standard deviation below the mean) on any standardized speech or language test were not included in the current study.

In addition, bilateral pure tone hearing screenings (i.e., 25 dB HL at pure-tone frequencies of 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz) were conducted to rule out hearing concerns. Participants were excluded if they did not perform within normal limits (American Speech– Language–Hearing Association (ASHA, 1990).

For talker group classification stuttered and non-stuttered disfluencies were counted in a speech sample consisting of at least 300 words as participants engaged in a conversational free play with the examiners. Participants were classified as CWS if they (a) exhibited three or more stuttered disfluencies (i.e., sound/syllable repetitions, sound prolongations,, or monosyllabic whole- word repetitions) per 100 words of conversational speech (Conture, 2001; Yaruss, 1998), and (b) scored 11 or greater (i.e., severity of at least “mild”) on the Stuttering Severity Instrument-3 (SSI-3; Riley, 1994).

Participants were classified as CWNS if they (a) exhibited two or fewer stuttered disfluencies per 100 words of conversational speech, and (b) scored 10 or lower on the SSI-3 (i.e., severity of less than “mild”).

2.3 Procedure

2.3.1 Stressful picture-naming task

During a laboratory visit, participants completed a picture-naming task involving 30 age-appropriate picture cards displaying simple objects or actions, after being instructed to name each picture as rapidly as possible. These instructions reflect the experimenters’ attempts to impose temporal, communicative and/or interpersonal pressure/stress on participants during the task, similar to what might be experienced by children in various communicative settings. The examiners avoided providing the participant with positive feedback and verbally encouraged the participants to “go faster” sporadically during the task. As soon as each picture card was placed on the table by the examiner, one at a time, the examiner held up the next card (with the back of the next card facing the participant), and encouraged the participant to name the card on the table as rapidly as possible. Immediately upon the participant’s naming the card on the table, the experimenter slapped the next card down on the table. In brief, the combination of experimenter instructions to “name the picture as fast as possible,” “go faster”, and holding the next card above and then slapping it down on the table constituted the experimenters’ attempts to impose stress on the participants during the task (for similar procedures used during clinical assessment of young children who stutter see Yaruss, 1997).

All 30 pictures were selected from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (PPVT-IV; Dunn & Dunn, 2007). A one-minute baseline skin conductance measure was collected at the beginning and at the end of the task, during which the participant was asked to sit still and wait for the examiner “to finish some paperwork.” At the end of the procedure, each participant was praised for his or her performance.

2.3.2 Equipment, data acquisition and processing

Bipolar electrodermal activity (EDA, i.e., SCL in this context) and acoustic recordings were acquired using a microphone and Biopac MP150 system (Biopac Systems, USA) connected to a Macintosh computer. Data were recorded using Acknowledge software (ver. 4.1 for Mac, Biopac). EDA was recorded with a pair of Ag-AgCl electrodermal electrodes (Model TSD203) filled with Biopac GEL101 electrode paste placed on the palmar surface on the distal phalange of the index and the fourth fingers3 of the participants’ left hand. No special preparation of participants’ palmar surface (e.g., cleaning with alcohol or abrasion of participants’ palmar surface) was employed due to the fact this is known to reduce the natural conductive properties of the skin (Dawson et al., 2007). The EDA electrodes were connected to a Biopac GSR100C skin conductance amplifier. EDA data collection procedures followed the guidelines recommended by Figner & Murphy (2011), Boucsein (1992) and Dawson et al. (2007). According to Boucsein (1992) and Figner & Murphy (2011), sampling rate should be no longer than 200 Hz and a low pass filter of 1 Hz should be applied. Therefore, EDA was sampled at 500 Hz, with the gain set at 10 µS/V and a low-pass filter at 1 Hz. The SCL data were expressed in microSiemens (µS). Skin conductance was synchronized with each participant’s acoustic recordings of his/her picture-naming responses. Ambient temperature in the testing room ranged from 18 to 24 °C, which is well within suggested guidelines for appropriate collection of EDA data (Boucsein, 1992; Dawson et al., 2007).

Intermittently, EDA data collection failed (e.g., if participants took off or pulled the electrodes during data collection), resulting in short intervals of missing data. Therefore, following data acquisition, each data file was inspected to identify whether there were any intervals of missing data. When this occurred, a linear interpolation technique (i.e., the “Connect Endpoints” math function of the Biopac Acknowledge 4.1 software) was used to estimate the missing data. Missing data intervals accounted for less than 5% of the total data. Following correction, EDA data were smoothed by applying a 125 Hz filter (i.e., upper cutoff at 125 Hz) to remove artifacts due to noise or sudden deflections. Following these procedures, a mean tonic SCL value for pre-task baseline, picture naming, and post-task baseline were calculated separately, after phasic responses were removed from the signal.

2.4 Dependent Measures

Skin Conductance Level: Pre-task baseline. Mean tonic SCL for 60 s prior to the presentation of the first picture card was measured.

Skin Conductance Level: Picture-naming task. Mean tonic SCL from the onset (i.e., presentation of the first picture card) until offset (i.e., participant’s response to the last picture card) was measured.

Skin Conductance Level: Post-picture-naming task. Mean tonic SCL for 60 s following the participant’s response to the last picture card was measured.

2.5 Independent Measures

Talker group (i.e., CWS and CWNS) and age group (i.e., 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds) were independent variables for this study. In the 3-year-old group, there were 18 CWS (6 females) and 12 CWNS (1 female). In the 4-year-old group, there were 10 CWS (2 females) and 16 CWNS (6 females). In the 5-year-old group, there were 9 CWS (1 female) and 11 CWNS (3 females).

2.6 Measurement Reliability

To establish high fidelity in data, trained judges identified and corrected artifacts by visually examining the data and applying Biopac artifact correction procedures when necessary (e.g., using, as mentioned above, the “Connect Endpoints” function when there is a short interruption in the data). The judges also verified that no more than 5% of the data was corrected. To assess the reliability of human judgment in artifact correction for the SCL data, 20% of the total final data corpus was randomly selected to determine inter-judge reliability between the first author and trained researchers (graduate-level or above). Intraclass correlation coefficient for tonic SCL during the task was .97, with a 95% confidence interval of .95 - .97, indicating high agreement among coders.

Speech-language pathologists collected speech fluency data (based on conversational free play) for talker group classification. Twenty percent of the total data corpus was randomly selected to determine inter-judge reliability for stuttering. Intraclass correlation coefficient for stuttered disfluencies was .957, with a 95% confidence interval of .86 – .98, indicating high agreement among coders.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

SPSS software was used (IBM Corp., 2012) and four separate statistical models were used to assess the four à priori hypotheses. The first hypothesis (i.e., all participants would have higher tonic SCL during the picture-naming task than the pre-task baseline and post-task conditions) was assessed using mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA). The second hypothesis (i.e., CWS’s overall basal sympathetic arousal level would differ from CWNS) was assessed using a two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with SCL during pre-task baseline as the dependent variable with talker group and age group as independent variables and gender as a covariate. The third hypothesis (i.e, CWS’s sympathetic arousal level during stressful picture-naming task would differ from CWNS) was assessed using two-way ANCOVA with SCL during task as the dependent variable and talker and age group as independent variables with participants’ pre-task baseline SCL values and gender as covariates. The fourth hypothesis (i.e., CWS’s sympathetic arousal level during post-task condition would differ from CWNS) was assessed using two-way ANCOVA with SCL during post-picture-naming task condition as the dependent variable, talker and age group as independent variables and pre-task baseline SCL values and gender as covariates.

Although the precise influence of chronological age on skin conductance in young children remains an open question, others have reported age-related differences in skin conductance in individuals 5 to 25 years of age (Venables & Mitchell, 1996). Likewise, El-Sheikh et al., in studies of autonomic behavior in children has also employed chronological age as an independent variable (e.g., El-Sheikh, 2005 & 2007; El-Sheikh & Arsiwalla, 2011). Given these precedents, chronological age was included as an independent variable in the between- and within-group analyses of skin conductance.

Because there are significant gender differences in speech-language development (e.g., Smit, Hand, Freilinger, Bernthal, Bird, 1990) and in the prevalence of stuttering, gender was taken into consideration in analyses of autonomic arousal related to speaking tasks. In addition, gender differences have been reported in autonomic arousal and emotional responses of children and adults (e.g., Arnold et al., 2014; Boucsein, 1992; Chentsova-Dutton & Tsai, 2007). Therefore, gender was a covariate in analyses of hypotheses 2, 3, and 4.

Wilder’s law of initial values suggests that baseline SCL values could influence subsequent SCL scores (Wilder, 1962). Therefore, to minimize any relation between baseline SCL and subsequent SCL values, baseline SCL was used as a covariate for the analyses of the third hypothesis that CWS’s overall SCL during picture-naming will differ from that of CWNS, and the fourth hypothesis (i.e., CWS’s overall level of sympathetic arousal during post-task will differ from that of their CWNS peers). This is consistent with the fact that there is inter-individual variance in SCL due mainly to physiological variables unrelated to psychological processes (e.g., thickness of the skin in recording area) (Lykken & Venables, 1971). Therefore, it is recommended to take baseline SCL values into consideration (Dawson et al., 2007), which it was in the present study.

Correction for multiple comparisons. Last, p-values of the follow-up pairwise comparisons were adjusted using the SAS Proc Multtest procedure to mitigate family-wise false discovery rate (i.e., Type 1 error; Westfall, Tobias, Rom, Wolfinger & Hochberg, 1999).

3. Results

3.1 Talker group characteristics: Speech fluency and Speech-Language

3.1.1 Speech fluency

One-way ANOVA compared CWS and CWNS on measures of speech disfluency. As would be expected based on participant classification criteria, there was a significant difference in frequency of stuttered disfluencies (per 100 words) between CWS (M = 5.9, SD = 3.43) and CWNS (M = 1.43, SD = 0.8), F (1, 74) = 62.484, p < .0001, η2 = .46 as well as a significant difference between SSI-3 scores for CWS (M = 15.2, SD = 4.1) and CWNS (M = 7.05, SD = 1.71), F (1, 74) = 130.77, p < .0001, η2 = .64. Also, there was a significant difference between CWS (M = 10.83, SD = 4.42) and CWNS (M = 5.23 SD = 3), F (1, 74) = 42.09, p < .001, η2 = .36 in frequency of total disfluencies. In addition, there was a significant difference between CWS (M = 5.09, SD = 2.3) and CWNS (M = 3.8, SD = 2.67), F(1,74) = 4.89 p < .05, η2 = .06 in frequency of non-stuttered disfluencies, consistent with a relatively large-scale empirical study of disfluency characteristics of young CWS and CWNS (Tumanova, Conture, Lambert, & Walden, 2014).

3.1.2 Speech and Language

One-way ANOVA compared CWS and CWNS on standardized speech and language scores. There were no significant differences between CWS and CWNS in GFTA-2 (F(1,74) = .705, p = .404), PPVT-IV (F(1,74) = 2.01, p = .16), EVT (F(1,74) = 1.65, p = .203), or the receptive and expressive subtests of TELD-3 (F(1,68) = .002, p = .97 and F(1,68) = .142, p = .708, respectively).

3.2 À priori hypotheses

3.2.1 Physiological Reactivity: Between-Conditions Comparisons for All Participants (Hypothesis 1)

A mixed-model ANOVA tested Hypothesis 1 that all participants-both CWS and their CWNS peers-would exhibit higher sympathetic arousal during the picture-naming than pre-task and post-task baseline conditions. This test assessed between-condition differences for all participants in tonic SCL among the three conditions (i.e., repeated measures: pre-task baseline, picture naming task, and post-task baseline). Tonic SCL was the dependent variable and age and talker group were independent variables.

Consistent with prediction, there was a main effect for Condition, indicating that tonic SCL differed among the three conditions; F(2, 149) = 4.848, p = .009, partial η2 = .032 (See Table 1). The condition x talker group interaction was also significant F(2, 214) = 4.298, p = .02, corrected for multiple comparisons (hereafter referred to as “corrected”). Table 1 provides means and standard deviations for tonic SCL for all (CWS+CWNS), CWS and CWNS participants.

Table 1.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for tonic skin conductance level (SCL, microSiemens) for the three study conditions.

| Skin Conductance Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Baseline | Picture-Naming-Task | Post-Baseline | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| ALL | 10.13 (4.8) | 12.48 (5.9)* | 12.17 (5.6)* |

| CWS | 10.10 (4.4) | 12.66 (5.7) | 12.58 (5.8) |

| CWNS | 10.21 (5.2) | 12.43 (6.2) | 11.89 (5.5) |

= p< 0.05

Note: All participants (n = 76, 57 male), CWS (n = 37, 28 male) and CWNS (n = 39, 29 male). Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference (i.e., p < .05) from pre-baseline.

Follow-up comparisons were conducted for the simple main effect of condition. The SAS Proc Multtest procedure (Westfall et al., 1999) adjusted p-values for these comparisons, with significance determined by the corrected alpha/p-value. As predicted, paired t-tests indicated that all participants exhibited significantly higher tonic SCL during the task (M = 12.48, SD = 5.9) than during the pre-task baseline (M = 10.13, SD = 4.8), t(75) = 9.38, p <.0002, corrected. However, contrary to prediction, tonic SCL for all participants did not differ between the picture-naming task and post-task baseline (M = 12.17, SD = 5.6), t(75) = 1.39, p = .168, corrected. Last, all participants’ post-task SCL was significantly higher than their pre-task SCL t(75) = 7.726, p <.0002, corrected.

3.2.2 Physiological Reactivity: Within-Condition comparisons of CWS and CWNS (Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4)

3.2.2.1 Pre-task baseline (Hypothesis 2)

ANCOVA tested Hypothesis 2 that CWS’s overall pre-task baseline SCL would differ from that of CWNS. The dependent variable was mean tonic skin conductance level during the pre-task baseline condition. Table 2 provides means and standard deviations for tonic SCL for CWS and CWNS. Independent variables were and age group, with gender as a covariate.

Table 2.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for tonic skin conductance level (SCL, microSiemens) for pre-task baseline condition for CWS and CWNS.

| Skin Conductance Level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year-olds |

4-year-olds |

5-year-olds |

Overall |

|||||

| M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | |

| CWS | 11.31 (4.2) | 18 | 10.15 (4.3) | 10 | 7.67 (4.2) | 9 | 10.10 (4.4) | 37 |

| CWNS | 10.59 (5.0) | 12 | 9.68 (5.3 ) | 16 | 10.56 (5.8) | 11 | 10.21 (5.2) | 39 |

Contrary to prediction (Hypothesis 2), there were no main effects of talker group (F(1,69) = .385, p = .60) or Age Group (F(2,69) = .664, p = .60) on pre-task tonic SCL. There was also no significant talker group x age group interaction (F(2,69) = 1.23, p = .29).

3.2.2.2 Picture-naming task (Hypothesis 3)

ANCOVA tested Hypothesis 3 that CWS’s SCL during the task would differ from that of CWNS (see Table 3 for talker group means and standard deviations for SCL). The dependent variable was mean tonic SCL. Independent variables were talker group and age group. Pre-task baseline SCL and gender were covariates.

Table 3.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for tonic skin conductance level (SCL, microSiemens) for between-group analyses of the picture naming condition for young CWS and CWNS.

| Skin Conductance Level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year-olds |

4-year-olds |

5-year-olds |

Overall |

|||||

| M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | |

| CWS | 13.17 (1.9) | 18 | 10.97 (1.6) | 10 | 10.03 (5.8) | 9 | 12.45 (2.1) | 37 |

| CWNS | 10.96 (2.0) | 12 | 12.43 (1.6) | 16 | 13.61 (7.1) | 11 | 12.33 (2.0) | 39 |

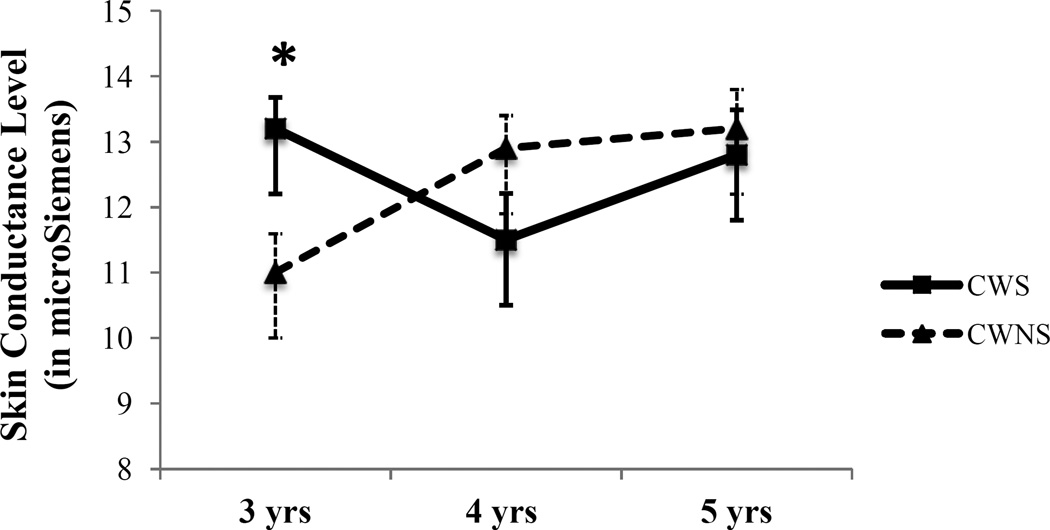

Contrary to Hypothesis 3, neither main effects of talker group (F(1,68) = .062, p = .80) nor age group (F(2,68) = 1.302, p = .28) reached significance for tonic SCL during the task. However, the talker group x age group interaction was significant F(2, 68) = 5.571, p = .006, corrected; η2 = .141. As illustrated in Figure 1, the 3, 4, and 5 year-old CWS and CWNS exhibited different levels of sympathetic arousal during the task. Thus, hypothesis 3 was partially supported in that the tonic SCL of CWS differed from that of CWNS during the task, with differences moderated by children’s chronological age. The significant talker group x age group interaction was followed up by between- and within-talker group simple comparisons of tonic SCL at ages 3, 4, and 5 for CWS and CWNS

Figure 1.

Mean (square and triangle) and standard error of the mean (brackets) tonic skin conductance level (SCL) during picture-naming task adjusted for the baseline SCL and gender. * indicates p< .05, corrected.

Note: For 3-year-olds (CWS = 18, 6 girls; CWNS = 12, 1 girl). For 4-year-olds (CWS = 10, 2 girls; CWNS = 16, 6 girls). For 5-year-olds (CWS = 9, 1 girl; CWNS = 11, 3 girls).

Between-group (i.e., CWS vs. CWNS) analyses of differences in tonic SCL during the picture-naming task for 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds.

Table 3 provides means and standard deviations for tonic SCL for all participants, CWS and CWNS at 3, 4, and 5 years of age.

3-year-old CWS vs CWNS’s tonic SCL during picture-naming task.

ANCOVA tested between-group (CWS vs. CWNS) differences in tonic SCL for 3-year-old participants, with pre-task baseline and gender as covariates. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, during the picture-naming task there was a significant main effect of talker group, with 3-year-old CWS (M = 13.17, SD = 1.99) exhibiting higher mean SCL than CWNS (M = 10.96 SD = 2) F(1, 26) = 8.53, p =. 035, corrected, η2 = .25.

4-year-old CWS vs CWNS’s tonic SCL during the picture-naming task. ANCOVA tested between-group (CWS vs. CWNS) differences in tonic SCL for 4-year-old participants, with pre-task baseline and gender as covariates. Inconsistent with Hypothesis 3, during the picture-naming task there was no significant main effect of talker group, with 4-year-old CWS (M = 10.97, SD = 1.61) mean SCL no different than CWNS (M =12.431, SD =1.6) F(1, 22) = 4.98, p = .07, corrected, η2 = .19.

5-year-old CWS vs CWNS’s tonic SCL during the picture-naming task. ANCOVA tested between-group (CWS vs. CWNS) differences in tonic SCL for 5-year-old participants, with pre-task baseline and gender as covariates. Contrary to Hypothesis 3, 5-year-old CWS (M = 10.03, SD = 5.76) did not differ in SCL from CWNS (M = 13.61 SD = 7.13) F(1, 16) = .004, p = .95, corrected, η2 < .0001.

Within-Group (i.e., CWS only; CWNS only) Analyses of Differences in Tonic SCL during the Picture Naming Task for 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds.

Children who stutter (CWS)

The significant talker Group x age interaction in the picture-naming task (Hypothesis 3) was further evaluated by assessing the simple main effect of age within each talker group using ANCOVA. Pre-task baseline SCL and gender were covariates.

3-year-old versus 4-year-old CWS tonic SCL during the task

Three-year-old CWS (M = 13.945, SD = 1.65) exhibited higher SCL than the 4-year-old CWS (M = 12.206, SD = 1.66), F(1, 24) = 6.961, p = .046, corrected; partial η2 = .23. An ANOVA was used to determine whether differences in stuttering frequency between 3- and 4-year-old CWS possibly contributed to these differences in SCL. Results indicated no significant difference in the frequency of stuttered disfluencies between 3-year-old CWS and 4-year-old CWS, F(1, 27)= .164, p = .69.

3-year-old versus 5-year-old CWS tonic SCL during the task.

There was no difference in tonic SCL between 3- (M = 14.46, SD = 5.47) and 5-year-old CWS (M = 10.03, SD = 5.76), F(1, 23) = .094, p = .84, corrected.

4-year-old versus 5-year-old CWS tonic SCL during the task.

There was no significant difference in tonic SCL between 4- (M = 10.17, SD = 2.4) and 5-year-old CWS (M = 10.03, SD = 2.4), F(1, 15) = .893, p = .51, corrected.

Children who do not stutter (CWNS).

3-year-old versus 4-year-old CWNS SCL during the task.

During the task 3-year-old CWNS (M = 10.937, SD = 2.07) did not exhibit significantly lower SCL than 4-year-old CWNS (M = 12.757, SD = 2.04), F(1, 24) = 4.97, p = .07, corrected, partial η2 = .172.

3-year-old versus 5-year-old CWNS SCL during the task. During the task, 5-year-old CWNS (M = 13.61, SD = 7.13) did not exhibit significantly higher skin conductance level than 3-year-old CWNS (M = 11.62, SD = 5.33), F(1, 19) = 4.72, p = .07, corrected, η2 = .20.

4-year-old versus 5-year-old CWNS SCL during picture-naming.

During the task, there was no significant difference in SCL between 5-year-old CWNS (M = 12.996, SD = 1.73) and 4-year-old CWNS (M = 12.67, SD = 1.73), F(1, 23) = .233, p = .79, corrected.

3.2.2.3 Post-task baseline (Hypothesis 4)

ANCOVA tested Hypothesis 4 that CWS’s overall SCL would differ from CWNS during the post-task baseline (see Table 4 for means and standard deviations for SCL). The dependent variable was mean SCL during the post-task baseline condition. Independent variables were talker group and age group. SCL during pre-task baseline and gender were covariates.

Table 4.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for tonic skin conductance level (SCL, microSiemens) for between-group analyses of the post-task baseline for young CWS and CWNS.

| Skin Conductance Level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year-olds |

4-year-olds |

5-year-olds |

Overall |

|||||

| M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | |

| CWS | 13.52 (2.3) | 18 | 11.81 (2.2) | 10 | 11.33 (2.3) | 9 | 12.22 (2.4) | 37 |

| CWNS | 11.25 (2.3) | 12 | 12.17 (2.3) | 16 | 12.01 (2.2) | 11 | 11.81 (2.3) | 39 |

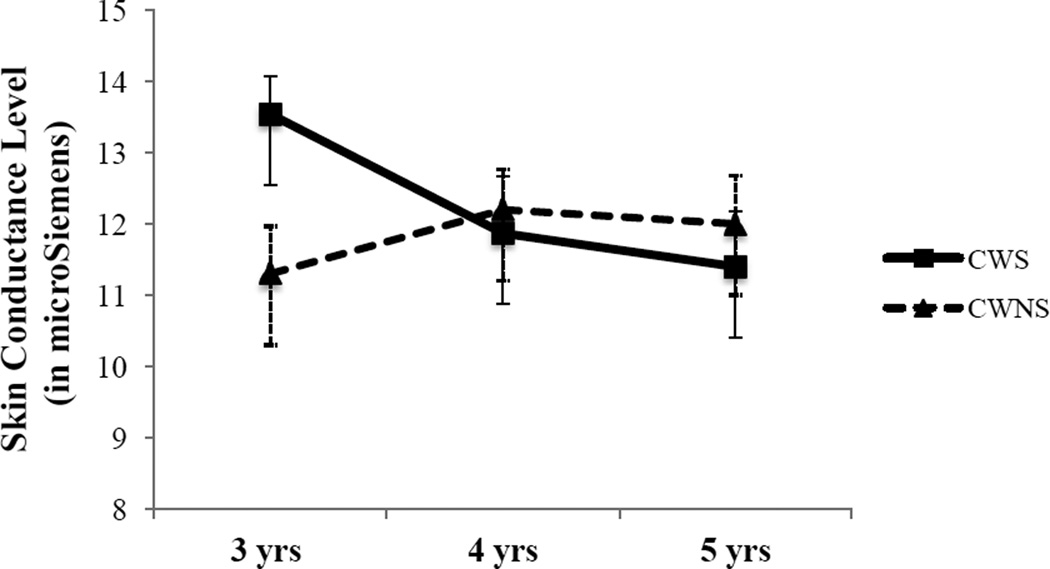

Contrary to prediction, during the post-task condition, neither main effects of talker group nor age group reached significance p =. 84 and p = .71 for tonic SCL. Likewise, the talker group by age interaction was not significant F(2, 68) = 3.09, p = .052, η2 = .083 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean (square and triangle) and standard error of meant (brackets) tonic skin conductance level (SCL) during post-task baseline adjusted for the covariates of pre-task baseline SCL and gender.

Note: For 3-year-olds (CWS = 18, 6 girls; CWNS = 12, 1 girl). For 4-year-olds (CWS = 10, 2 girls; CWNS = 16, 6 girls). For 5-year-olds (CWS = 9, 1 girl; CWNS = 11, 3 girls).

3.3 Ancillary Analyses

Findings pertaining to five variables: (1) picture-naming accuracy (2) receptive and expressive vocabulary, (3) time since onset of stuttering (TSO), (4) chronological age and (5) task duration are presented below. These variables were analyzed because of their potential impact on tonic skin conductance level (SCL).

For all of these associations (3.3.1 – 3.3.5), “SCL” refers to residualized change scores instead of raw SCL values during the task. Residualized change scores were employed to control for the participants’ baseline SCL. Hereafter, residualized SCL scores will be referred to as “SCL” throughout the results. This method used the residuals of the regression equation where participants’ pre-task baseline SCL values were used to predict their SCL values during picture-naming task.

3.3.1 Association (for all participants: CWS + CWNS) of picture naming accuracy & SCL

Picture-naming accuracy was not analytically considered as an independent variable nor a covariate since the pictures were age-normed and correctly identified by the majority of children. Nevertheless, it could also be argued that age effects on SCL during picture-naming task could result from the relative difficulty of the picture-naming task for younger versus older children.

To explore this possibility, approximately 25% of the total corpus of picture-naming responses was selected randomly (n = 18, three 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old CWS and CWNS) and the accuracy of these responses (i.e., number correct divided by total number of pictures) was assessed in relation to tonic SCL. A Pearson correlation coefficient yielded no correlation between tonic SCL and picture-naming accuracy during the task, r = −.017, p = .49.

3.3.2 Association (for all participants: CWS + CWNS) of receptive and expressive vocabulary and tonic SCL during the task

Individual differences within and between groups in terms of receptive and expressive vocabulary could impact children’s SCL during picture-naming due to perceived difficulty of the task (though there were no group differences for receptive and expressive vocabulary).

To assess this possibility, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were computed for each age group and talker group to assess the relation between SCL during the task and receptive (i.e., PPVT-IV) and expressive (i.e., EVT) vocabulary. During the task (the condition associated with the greatest number of between-group differences in tonic SCL), there were no significant correlations between SCL and raw scores on PPVT-IV and EVT for either talker group or age group (Pearson’s r values ranged from .006 to −.059 for PPVT and .056 to −.585 for EVT. See Table 5 for correlations for each group).

Table 5.

Correlations (Pearson product-moment; r) between skin conductance level (SCL; i.e., residual change scores relative to baseline) and receptive (PPVT-IV) and expressive (EVT) vocabulary for young CWS and CWNS during picture-naming task.

| PPVT | EVT | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | −0.22 | −0.20 | 37 | |

| CWS | 3-year-olds | 0.21 | 0.36 | 18 |

| 4-year-olds | 0.09 | −0.37 | 10 | |

| 5-year-olds | −0.60 | −0.59 | 9 | |

| Overall | 0.16 | 0.06 | 39 | |

| CWNS | 3-year-olds | 0.37 | 0.45 | 12 |

| 4-year-olds | −0.09 | −0.08 | 16 | |

| 5-year-olds | 0.06 | −0.28 | 11 | |

= p< 0.05.

3.3.3 Association between Time Since Onset (TSO) of Stuttered Disfluencies and tonic SCL (CWS only)

Although chronological age was considered as a covariate in various analytical assessments of à priori hypotheses, it could be argued that chronological age might be a “proxy” for “experience with stuttering” or time since onset (TSO). TSO information was obtained using the bracketing procedure reported by Yairi & Ambrose (1992) and Anderson, Pellowski, Conture & Kelly (2003).

TSO was available for 29 of the 37 CWS, with missing TSO data for 8 CWS related to a variety of issues involving parental compliance and/or apparent error in reliability of parental reports. Within-group analyses for CWS during the picture-naming task indicated no significant correlation between TSO and SCL, r= −.259, p= .244, suggesting that TSO does not readily account for the present findings that chronological age impacts tonic SCL.

3.3.4 Association between chronological age and SCL (Within-group: CWS only; CWNS only)

It was conjectured that the significant talker group by age interaction could be related to group differences in the association between age and skin conductance. To test this possibility, correlations between age and SCL were made for each talker group separately for each of the three conditions (i.e., baseline, task and post-task).

For the CWNS, there was no significant correlation between chronological age and SCL during any of the three conditions (p values ranging from .92 to .45).

For the CWS, however, there was a significant negative correlation between age and SCL during post-task baseline (r = −.381, p = .02, see Figure 3), with a similar negative, but nonsignificant trend during pre-task baseline (r =−.311, p = .06) and picture naming task (r = −.32, p = .05). This indicates that at least for CWS, post-picture naming task SCL (i.e., 60-s recovery period after the picture-naming task) is negatively correlated with chronological age (i.e., the younger showed greater SCL, thus less recovery from task).

3.3.5 Association between duration of picture-naming task and tonic SCL

For the 76 participants (37 CWS + 39 CWNS), the total duration of the task varied, leading to individual differences in duration. To determine whether differences in duration of the task impacted tonic SCL, two analyses were conducted: (1) between-group differences in duration of the task and (2) association of task duration and tonic SCL for all participants.

First, one-way ANOVA indicated that CWS took significantly longer (M= 85.5 seconds, SD=21.9) to name the 30 pictures than their normally fluent peers (M= 72.46 seconds, SD=17.67); F(1, 74) = 8.17, p= .006, a finding consistent previous findings that children and adults who stutter exhibit longer reaction times (RTs) during a variety of (non-speech tasks (e.g., Bloodstein & Bernstein Ratner, 2008; van Lieshout, Ben-David, Lipski, Namasivayam, 2014).

Second, there was no correlation between picture-naming task duration and tonic SCL during the task, r=.008, p=.95 for all participants, for CWS (r=.007 p=.97) and for CWNS (r=.004 p=.98). Equally noteworthy, when task duration was covaried for all participants, the talker group x age group interaction remained significant (F(2,67)= 5.218, p= .009).

4. Discussion

4.1 Summary of Main Findings

The study resulted in four main findings. First, both CWS and CWNS exhibited greater tonic SCL during the task than the pre-task, but not post-task baseline. Second, during the pre-task baseline, CWS’s tonic SCL did not differ from that of their CWNS peers. Third, during the task, CWS’s SCL did not differ from that of their CWNS peers. However, when chronological age was taken into account; 3-year-old CWS exhibited significantly greater SCL than their CWNS peers and greater than 4-year-old CWS. Fourth, during the post-task baseline, CWS’s tonic SCL did not differ from CWNS. Implications of these findings are discussed below.

4.1.1 Physiological reactivity: Between condition differences for all participants (first main finding)

Consistent with prediction (Hypothesis 1), present findings indicated that all children (i.e., CWS and CWNS) exhibit greater sympathetic arousal during the stressful picture-naming task than the pre-task baseline. Therefore, this study’s picture-naming task was associated with greater sympathetic arousal than during baseline. Thus, this finding appears to validate that the presently employed stressful picture-naming task was challenging for young children who do and do not stutter. This suggests that the procedure may be useful in future empirical research in which the association of emotional arousal, stress and childhood stuttering are of interest.

4.1.2 Physiological reactivity: Pre-task baseline (second main finding)

Present results did not support the prediction that CWS would differ from their CWNS peers in sympathetic arousal during the pre-task baseline. Even when chronological age was taken into account, there were no between-group differences in SCL during the pre-task baseline. It is possible that the singular study of young children’s SCL during baseline (i.e., “resting state”) may result in too restrictive a perspective on the association of autonomic reactivity and childhood stuttering. A better approach might be to study the degree to which sympathetic activity (e.g., SCL) is associated with parasympathetic activity (e.g., respiratory sinus arrhythmia) during baseline or a resting state. Studying physiological activity during baseline or resting states has been shown to be profitable in the study of functional connectivity within the brain during resting states (e.g., Biswal, Yetkin, Haughton, & Hyde, 1995; DiMartino, Scheres, Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, & Shedzad, 2008; Kim, Loucks, Palmer, Brown, Solomon, Marchante & Whalen, 2011). Be that as it may, present findings suggest that CWS and CWNS exhibit comparable levels of tonic SCL/autonomic reactivity when presented with relatively neutral, non-specific instructions to “wait until the examiner is done with paperwork.”

4.1.3 Physiological reactivity: Picture-naming task (third main finding)

The initial prediction that CWS and CWNS would differ in tonic SCL during the picture-naming task was supported only when chronological age was taken into account. Specifically, the effect of talker group (CWS vs. CWNS) on tonic SCL during the task was moderated by chronological age. That is, 3-year-old CWS exhibited significantly higher tonic SCL than 3-year-old CWNS. On the contrary, neither the 4-year-old nor the 5-year-old CWS differed in SCL from their normally fluent CWNS.

The apparent impact of chronological age on between-group differences in tonic SCL challenges straightforward explanation. One such challenge is that there are several means to achieve changes in tonic SCL. For example, one can exhibit relatively higher SCL as a more or less habitual trait; whereas another individual may exhibit higher SCL due to reduced physiological regulation. Neither present methodology nor data readily helps us determine which of these mechanisms, if either, best account for the current findings.

For example, in the present study, 3-year-old CWS exhibited significantly higher SCL than 3-year-old CWNS. There are at least two alternative accounts for these differences. Three-year-old CWS may exhibit less efficient physiological regulation than 3-year-old CWNS. In other words, during a relatively stressful speaking task, CWS may less effectively engage regulation or parasympathetic activity to support their “social-communicative” system, with such regulatory activities thought to check, dampen or minimize arousal or sympathetic activity, the latter thought to support individuals’ “mobilization” system (see Porges, 2007, for further review of such sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions). Perhaps the sympathetic system is activated by the young speakers in response to perceived challenge or stress of the speaking task (without appropriate activation of parasympathetic “checking” or regulation), a possibility that must await further empirical study.

An alternative account is that relative to their CWNS peers, 3-year-old CWS may exhibit higher tonic SCL in reaction to the stressful speaking task because of their experiences with and/or learned reactions to their stuttering. This is not a particularly compelling account given the fact that 3-year-olds, generally speaking, have less experience with stuttering than 4- and 5-year-old children who stutter; nevertheless the possibility remains that 3-year-olds’ experiences with/learned reaction to stuttering impacted their tonic SCL. Whatever the case, further determination of such possibilities must await future empirical investigation4.

Present findings also indicated that relative to 4-year-old CWS, the 3-year-old CWS had higher sympathetic arousal during the rapid picture-naming task. Perhaps 3-year-old CWS were simply more aroused by the stressful picture-naming task than 4-year-old CWS. Alternatively, as suggested above, the higher SCL of 3-year-old CWS may result from less effective emotion regulation strategies. This implies that younger children (i.e., 3-year-olds) who stutter are relatively less emotionally regulated but that with continued development, their regulatory abilities improve. If such developmental change does occur for CWS, we still do not know whether these developmental differences are associated with other behavioral, cognitive or physiological processes, for example, attentional processes (e.g., selective inattention to emotional stimuli), cognitive processes (e.g., cognitive appraisal of the aversive or rewarding aspects of stimuli) or some combination of the both (Ochsner & Gross, 2005, p. 243).

4.1.4 Physiological reactivity: Post-task baseline (fourth main finding)

Similar to the findings of sympathetic arousal in the pre-task baseline, current results did not support our prediction that during the post-task baseline CWS would differ from their CWNS peers in sympathetic arousal. When chronological age was taken into account for the post-task baseline, a talker group by age interaction was also not significant (p = .07). Thus, it remains an open empirical question whether given a longer post-task baseline (i.e., > 60 seconds), whether the tonic SCL of CWS and CWNS would show (1) a group by age interaction, or (2) return to their respective pre-task baseline levels.

4.1.5 Comparison of present findings regarding SCL in young CWS to that of previous studies of SCL in older people who stutter

Although it is difficult to directly compare present findings with young children to those with adults, there are at least two findings comparable in the literature on children and adults. First, the present study’s findings that children exhibited greater SCL during talking than a non-talking baseline is consistent with previous reports of SCL for both adults who stutter (AWS) and adults who do not stutter (AWNS) (Peters et al., 1984; Weber & Smith, 1990) during speaking relative to baseline or other task conditions5. Second, the present findings of no significant talker-group differences in non-talking baseline conditions (pre- and post-task) are also consistent with previous reports of no differences in SCL under such conditions for AWS and AWNS (Gray & Karmen, 1967; Peters & Hulstjin, 1984, Weber & Smith, 1990). Still, direct comparisons in SCL across the lifespan for people who stutter remains challenging, at least regarding extant published findings. Perhaps, in future studies in this area, comparable, but age-or developmentally-appropriate tasks (e.g., picture-naming) can be used for preschool-age, school-age, teenage and adults who stutter. In this way, results from comparable, but age-adjusted tasks, may better permit researchers to compare similarities/differences in SCL across the lifespan of people who stutter.

4.2 General Discussion

In general, tonic skin conductance level represents one well-established psychophysiological index of emotional reactivity (e.g., Boucsein, 1992; Dawson et al., 2007; Porges, 2007). Such reactivity, however, does not operate in a vacuum, but in the context of emotional and attentional regulation (Rothbart, 2011). That is, emotional reactivity can be down regulated by appropriate emotional regulation, including the use of attentional shifting (directing attention away from an arousing or distressing stimulus) and focusing (redirecting attention toward a non-arousing stimulus). Thus, it appears appropriate to provide some discussion of present findings regarding reactivity within the context of these regulatory processes. This seems particularly germane given the following two general findings: (1) emotion regulation differs between preschool-age CWS and CWNS (Eggers et al., 2010; Karrass et al., 2006) and (2) changes in preschool-age CWS’ emotion regulation have been shown to be associated with changes in CWS’ frequency of stuttering (Arnold et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2010; Walden et al., 2012; Ntourou et al., 2013).

Specifically, when compared to their CWNS peers, preschool-age CWS exhibit (a) less ability to regulate their emotions (Karrass et al., 2006) and (b) lower inhibitory control (Eggers et al., 2010). Furthermore, preschool-age CWS exhibit greater stuttering in association with (a) decreased frequency and duration of regulatory strategies (Arnold et al., 2011), (b) greater negative emotion accompanied by lower emotion regulation (Walden et al., 2012), and (c) during conditions requiring more emotion regulation (speaking after receiving a disappointing gift: Johnson et al., 2010; speaking after experiencing a frustrating task: Ntourou et al., 2013).

One regulatory process of particular salience to early childhood development is that of effortful control, the ability to suppress a dominant response (inhibitory control) in order to perform a subdominant response (activation control), to detect errors and to engage in planning (Rothbart, 2011). Effortful control is believed to emerge during the first two years of life, and it develops in parallel with other executive function skills such as attention. Therefore, as children mature, their effortful control increases, with one key element of effortful control being that of inhibitory control (i.e., ability to inhibit a prepotent or dominant response).

The relevance of such regulatory processes to childhood stuttering/present findings may be seen in a large-sample, empirical study of 3-year-old children, with results indicating that relative to behaviorally uninhibited children, behaviorally-inhibited children showed higher skin conductance levels (Scarpa, Raine, Venables, & Mednick, 1997). Similarly, a recent investigation of behavioral inhibition in preschool-age CWS and CWNS reported that there were more CWS with high behavioral inhibition6 (BI) and fewer CWS with low BI than their CWNS peers (Choi et al., 2013). At present, it is unclear how Choi et al’s findings relate to the present finding that 3-year-old CWS exhibit higher SCL than their CWNS peers. However, in future empirical studies, concurrent measurement of CWS and CWNS’s behavioral inhibition and SCL may help clarify the relation, if any, between behavioral inhibition, SCL and childhood stuttering.

Future empirical studies that concurrently measure emotion regulation (e.g., respiratory sinus arrhythmia, Jones et al., 2014b) as well as emotional reactivity (e.g., skin conductance) may help disentangle the relation between emotional arousal and regulation with regard to childhood stuttering. Specifically, such study should help discern between-group (CWS vs. CWNS) differences, if any, in the classic oppositional pattern (e.g., low emotional regulation and high emotional reactivity) of autonomic activity. Differences from expected patterns could possibly take several forms, for example, co-activation of both sympathetic and parasympathetic aspects of the autonomic nervous systems. Whatever the case may be, determination of such possibilities must await future empirical study.

4.3 Caveats

The present study assessed physiological reactivity during a stress-inducing picture-naming task rather than a narrative or conversational speaking task. Certainly, picture naming provides relatively good control over speaking stimuli. Such control may be offset, however, by the fact that preschool-age CWS have been shown to be fairly fluent during the single-word responses such as “yes” “no” or as in a picture-naming task when compared to running speech in a conversational sample (Yaruss, 1998; Lee, 1974). Therefore, with regard to stuttering, the present picture-naming task may not have created a particularly challenging speaking condition for young children. This suggestion is supported by the present authors’ observation that there was relatively little stuttering during the present study’s picture-naming task. Thus, it was not possible to meaningfully assess the association between instances of stuttering and tonic SCL during the present picture-naming task. Indeed, if there had been sufficient instances of stuttering during the picture-naming task to permit inferential statistical analysis - which there were not – it may have been more feasible to employ phasic as well as tonic measures of SCL. It will be recalled that present findings were based on a cross-sectional rather longitudinal data sample. Therefore, present speculation about the association between chronological age and physiological reactivity are suggestive, rather than conclusive. Going forward, it would seem helpful to explore physiological reactivity in a longitudinal study to find out whether CWS and CWNS follow different developmental trajectories in terms of physiological associates of emotion reactivity, especially in relation to concurrent development of physiological associates of emotion regulation.

Also, there was no systematic blinding of examiners who administered the stressful picture-naming task to the diagnosis of stuttering. There is no empirical evidence in the present study that examiners were biased for (or against) one versus another talker group in the experimental application of stress, time pressure, or similar psychological variables. Indeed, the experimenters attempted to deliver comparable degrees of stress/time pressure to all participants by providing instructions to go faster at comparable times and in a similar manner across all participants. Nevertheless, it may be prudent, for future studies using the present paradigm, to employ systematic blinding of examiners to talker groups (to the extent possible when one group clearly or overtly stutters more than the other) to avoid the possibility of such bias.

Lastly, the duration of the pre- and post-task baseline conditions was 60 seconds. It is possible that this period of time was too short for acquisition of a representative pre- or post-task baseline for physiological reactivity. Future studies may want to consider acquiring baseline data for longer than 1 minute (e.g., El-Sheikh, Keiley, Hinnant, 2010). To our knowledge, there are no previous studies of skin conductance that empirically assessed the optimal amount of time required for establishing/assessing SCL baselines, especially in young children. This represents a methodological gap in our understanding that will require further empirical study.

4.4 Conclusions

Present findings regarding SCL and stuttering are most appropriately viewed as relating to this sample of young CWS and CWNS, as well as the present study's specific task conditions. Hence, results based on samples of different ages, gender, and tasks/conditions may differ from those presently reported. With that caveat in mind, present physiological findings seem consist with non-physiological findings suggesting an association between emotional arousal and childhood stuttering in young children. Specifically, 3-year-old CWS demonstrated significantly higher reactivity during the rapid-picture naming task than their CWNS peers, and their 4-year-old CWS peers, whereas no between-group differences were found for the 4-year-old and 5-year-old participants. Thus, a comprehensive physiological assessment of the association between sympathetic arousal and childhood stuttering should take chronological age into consideration for both within- and between-group analyses.

Such consideration, especially for young children who stutter, may also have implications for the association of sympathetic arousal and recovery and/or persistence of stuttering, implications that must await further empirical investigation. Of particular note, emotional reactivity occurs in the context of emotional and attentional regulation, and is probably best understood within that context. Therefore, future empirical studies of the association of emotional arousal and childhood stuttering may want to consider the possible moderating or mediating effect that attentional and/or emotional regulation has on this association. The present authors believe that the results of such empirical studies – employing converging lines of evidence from behavioral, parent and psychophysiological indexes of emotional reactivity and emotional regulation – should help develop a more comprehensive understanding of the association between emotion and stuttering in young children.

Highlights.

Sympathetic arousal of young CWS and CWNS was measured during a stressful picture-naming task.

When chronological age was taken in account, there were significant between-group differences for 3- year-olds during picture naming condition.

Physiological associates of emotional reactivity significantly differentiate CWSs from CWNSs picture naming responses suggesting that emotional processes are related to the trait of childhood stuttering.

Educational Objectives.

After reading this article, the reader will be able to: (1) discuss salient findings in the literature regarding the association between emotional processes and childhood stuttering; (2) discuss sympathetic arousal, and how skin conductance is used to measure it; and (3) discuss the role of chronological age in the association between emotion and stuttering in young children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDCD/NIH research Grants, R01 DC000523-17, R01 DC006477-01A2; as well as the National Center for Research Resources, a CTSA grant (1 UL1 RR024975-01) to Vanderbilt University that is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The research reported herein does not reflect the views of the NIH, NCHD, or Vanderbilt University.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ellen Kelly for reviewing earlier drafts of this article, Dr. Warren Lambert for his help with statistical analyses, Samara Nichols and Laurie Phebus for their assistance in inter-rater reliability for disfluency coding and skin conductance data analysis. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the participants who made this study possible.

Biographies

Hatun Zengin-Bolatkale received her M.A. in Speech and Hearing Science from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences at Vanderbilt University. Her primary research interest is investigating childhood stuttering, using social/cognitive developmental neuroscience methods.

Edward G. Conture is a Professor Emeritus at the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences at Vanderbilt University. Dr. Conture is an ASHA fellow and has received the Honors of the Association. His research focuses on childhood stuttering, particularly emotional and/or psycholinguistic contributions to stuttering.

Tedra A. Walden is a professor of Psychology at Peabody College at Vanderbilt University and a senior fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Studies. Dr. Walden’s research focuses on social and emotional development of young children and the role of emotions in childhood stuttering.

Appendix

Question 1: Correct Answer = c

Question 2: Correct Answer = b

Question 3: Correct Answer = a

Question 4: Correct Answer = e

Question 5: Correct Answer = c

Continuing Education Questions

-

Which of the following is NOT a methodology typically employed in empirical studies of the association between emotion and childhood stuttering?

caregiver reports

skin conductance

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

coded behavioral observations

electroencephalography (EEG)

-

Skin conductance measures activity of the sympathetic branch of the _______________.

parasympathetic system

autonomic nervous system

central nervous system

gastrointestinal system

lymphatic system

-

Present findings indicated that during a stressful picture naming task, that 3 year-old CWS, when compared to their CWNS peers,

exhibited significantly higher sympathetic arousal

exhibited significantly lower sympathetic arousal

were not significantly different in their sympathetic arousal

were significantly better at effortful control

exhibited significantly lower stuttered disfluencies

-

The current study found no overall significant difference in sympathetic arousal during picture naming task between young CWS and CWNS when chronological age was not taken into account. However, when chronological age was taken into account, there were significant talker group differences between 3-year olds. Which of the following statements best explain these diverging findings?

Skin conductance is not a reliable method to measure emotional arousal.

Children who do not stutter are more resilient to the temporal and interpersonal stress aspects of the task.

The picture naming task used in this study is not an arousing task for the children in this study.

Children who do not stutter exhibited significantly better effortful control relative to their CWNS peers.

Comprehensive physiological assessments of CWS require consideration of the interaction between chronological age and talker group.

-

Rothbart (2011) states that emotion reactivity operates in the context of emotional and attentional regulation. Based on Rothbart’s statement one might suggest that

Children who stutter are significantly better at attention regulation than their CWNS peers.

Prefrontal lobe regulates all aspects of emotional processes.

Future studies of emotion regulation may help explain present between-group differences in emotion reactivity.

Attentional processes are highly involved in other cognitive processes such as working memory and vigilance.

Children who stutter have not been shown to be significantly different from their CWNS peers in attention and emotion regulation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Although some of these measures relate to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Ortega & Ambrose, 2011; van der Merwe et al., 2011) and others to cortical activity (e.g., frontal alpha asymmetries) (Arnold et al., 2011) associated with emotion, neither HPA axis activity nor cortical activity were the theoretical or methodological focus on the present study. For further review of these processes, the reader interested in HPA axis activity is referred to Ledoux (1998, Figure 8-1) and Barr (2012, p. 263–264) and for cortical activity associated with emotion Cacioppo, Tassinary & Bernston (2007, pp. 56–84).

Electrodermal activity (EDA) can be measured by means of skin conductance level (SCL), with the two basic measures of SCL: (1) tonic (i.e., sympathetic arousal of a relatively stable character and not changing within short time-ranges and not dependent on stimulus conditions and (2) phasic (i.e., momentary fluctuations in EDA, evoked sympathetic response to stimuli or stimulus conditions) (Handler et al., 2010). For the present study, to assess overall across-condition (Hypothesis 1) as well as between-group (Hypotheses 2–4) differences in SCL, the more general or “mean” index, that is, tonic SCL was employed. Furthermore, given the approximately 1–3 s delay between stimulus onset and onset of phasic skin conductance response (SCR) and SCL (e.g., Boucsein, 1992; Dawson et al., 2007), reliable measurement of phasic SCR associated with individual naming responses, the latter often occurring under 1 s from stimulus onset (i.e., picture slapped on table), was considered untenable.

Distal phalange site is recommended due to the larger number of sweat glands relative to other recording sites (e.g., Dawson et al., 2007).

It should be noted that speculation regarding between-group differences during picture-naming being moderated by age, was put forth strictly in relation to physiological associates of emotion. Findings based on other measures of emotional processes (e.g., parent report, coded behavioral observations) – as mentioned above re “converging lines of evidence” – may, and most likely do, provide different perspectives on the influence of chronological age on emotional processes. It is thought by the present authors that findings based on all such measures will need to be considered together to obtain the most comprehensive understanding of emotion and childhood stuttering.

Consistent with some of these findings re AWS, related studies of adults who do not stutter and children who do not stutter Arnold et al. (2014) and Kleinow & Smith (2006) reported higher autonomic arousal during challenging speaking conditions relative to other non-speaking conditions and non-challenging speaking conditions.

Behavioral inhibition is defined as a temperamental characteristic of exhibiting initial avoidance and distress in unfamiliar places, situations or the presence of unfamiliar people by Kagan et al., 1984 (in Choi et al., 2013). It can be measured in various ways, for example, latency to the sixth spontaneous comment during social interaction.

Contributor Information

Hatun Zengin-Bolatkale, Email: hatun.zengin@Vanderbilt.Edu.

Edward G. Conture, Email: edward.g.conture@Vanderbilt.Edu.

Tedra A. Walden, Email: tedra.walden@Vanderbilt.Edu.

References

- Adams MR, Moore WH. The effects of auditory masking on the anxiety level, frequency of dysfluency, and selected vocal characteristics of stutterers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1972;15:572–578. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1503.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Guidelines for screening for hearing impairment and middle-ear disorders. In ASHA. 1990;32:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Pellowski M, Conture E, Kelly E. Temperamental characteristics of young children who stutter. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2003;45:20–34. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/095). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold HS, Conture EG, Key APF, Walden T. Emotional reactivity, regulation and childhood stuttering: a behavioral and electrophysiological study. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2011;44:276–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold HS, MacPherson MK, Smith A. Autonomic correlates of speech versus nonspeech tasks in children and adults. Journal of Speech Language, and Hearing Research. 2014;57:1296–1307. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-S-12-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr C. Temperament in animals. In: Zentner M, Shiner R, editors. Handbook of Temperament. New York: The Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Berlinsky SL. A comparison of stutterers and non-stutterers in four conditions of experimentally induced anxiety. UMI Dissertation Services. 1954 No. AAT 0007604. [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin F, Haughton V, Hyde J. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magnetic Resonance Medicine. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodstein O, Bernstein Ratner N. A handbook on stuttering. 6th. Thomson-Delmar; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boucsein W. Electrodermal Activity. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Brutten EJ. Palmar sweat investigation of disfluency and expectancy adaptation. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1963;6:40–48. doi: 10.1044/jshr.0601.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG, Klein DJ, Poehlmann KM. The psychophysiology of emotion across the lifespan. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1997;17:27–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, Berntson GG. Handbook of Psychophysiology. 3rd. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]