Short abstract

BBC 1, Wednesdays at 10 35 pm from 14 to 28 July

Rating: ★★★

Each of these three documentaries, which focus on rare medical conditions, is rather like a whodunit, where the mystery unfolds, is subsequently investigated, and, in a sense, solved.

The first episode covered the much debated madness of King George III. Professors Tim Cox of Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, and Martin Warren of Queen Mary's, London, set out to find the truth about the king's condition, which is widely thought to have been caused by acute intermittent porphyria. The story began with the recent unearthing of samples of the king's hair in a London museum vault. The hair was analysed and found to have 300 times the amount of arsenic when compared with controls. Painstaking searches through the history books revealed a number of odd findings: that many creams and oral therapies contained arsenic in the 18th century; that a distant relative of the king, who also had symptoms of porphyria, was once therapeutically injected with arsenic and almost died from an acute attack as a direct result; that the powder used to whiten the king's wig contained arsenic; that the drug doctors used to treat the king's condition (Dr James's fever powder) contained antimony, which contained arsenic.

In addition to the fascinating detective work, there is a substantial human element in all three programmes. Julie Bradshaw has acute intermittent porphyria and her patient's perspective helped to illustrate the effects of the illness.

Figure 1.

Fighting the establishment: actress Susan Sarandon as Michaela Odone in the film Lorenzo's Oil

Credit: KOBAL

Programme two was about Lorenzo's oil, a medication used in the treatment of adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), which is a progressive X linked neurological condition that leads to paralysis, blindness, and early death. It is caused by a relative excess of very long chain fatty acids and usually presents before the age of 8.

Lorenzo is the 26 year old son of Americans Augusto and Michaela Odone, both non-medics, who fought a battle against the medical establishment to find a cure for ALD. Not willing to accept that there was no treatment for the condition, the Odones did their own extraordinary research and proposed that mixing erucic and oleic acid was a potential cure. In the early 1990s their courage was captured in the Hollywood film Lorenzo's Oil which, like this programme, showed their journey from local libraries to an industrial firm in Hull, England—the only company that initially agreed to manufacture the oil. There was widespread dissent among the medical profession, but the latest research conducted in this programme showed that ALD, although not treatable, may be prevented by Lorenzo's oil in those who carry the gene but are asymptomatic.

Again the story of other patients served to illustrate the impact of the condition, and there was hope for one sibling who has so far kept the disease away by taking the oil since positive genetic testing. The narrative technique of following patients and their relatives on their medical journey—a technique that runs through all three programmes—is intensely powerful and occasionally overwhelming.

The final episode appears to have been made over several years. It tracks the research of two medical teams into the cause of encephalitis lethargica, a strange neurological condition causing coma and catatonia, of which there was a pandemic between 1917 and 1928. The next reported batch of cases was in New York in the late 1960s. These are gracefully discussed by neurologist and author Dr Oliver Sacks, who first experimented treating these patients with L-dopa. The condition randomly reappeared at Charing Cross Hospital in 1993 with the case of Becky Howells. There is footage from her admission and a sense of helplessness as her consultant describes her initial despair when Becky first presented.

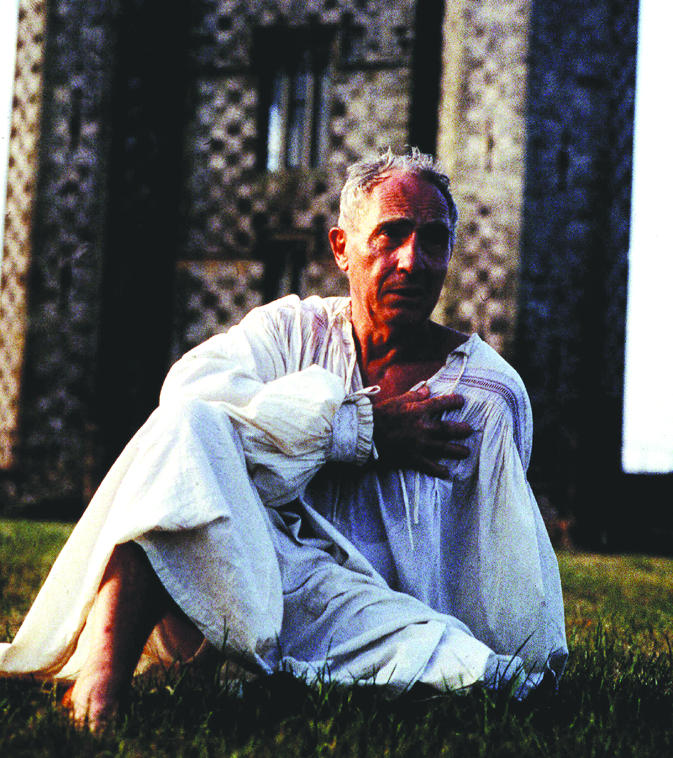

Figure 2.

Does porphyria explain George III's madness?

Credit: KOBAL

The initial theory of influenza virus as the root cause (there was a flu pandemic in the 1920s at the same time as the pandemic of encephalitis lethargica) was discounted after Professor John Oxford of Queen Mary's, London, was unable to isolate the virus from brain segments of sufferers from the 1920s. Amazingly, scientific and historical research carried out at the Institute of Neurology and Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, respectively, showed that encephalitis lethargica was almost certainly a post-streptococcal phenomenon.

Each programme ends on a positive note, with new knowledge or a heart-warming glimmer of hope. Yet an odd sense of darkness overshadows the whole production, amplified by the choice of music, title sequences, and a dramatic voiceover.

The difficulty with making this kind of series is its sheer enormity in terms of time, research, consent, planning, and making it palatable enough to appeal to a wide viewership. There are interesting slivers here for everyone—for those who enjoy history, epidemiology, documentaries, the patient's story, medical advances, and much more beyond.

The series is also a refreshing reminder that solving medical mysteries is not just a thing of the past, and that in the future similar programmes might be made about curing AIDS or the common cold.