Summary

Background

Elevated levels of endothelial cell (EC)-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) circulate in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs), and APLAs, particularly those against β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), stimulate EV release from ECs. However, the effects of EC-derived EVs have not been characterized.

Objective

To determine the mechanism by which EVs released from ECs by anti-β2GPI antibodies activate unstimulated ECs.

Patients/methods

We used interleukin (IL)-1 receptor inhibitors, small interfering RNA (siRNA) against Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and microRNA (miRNA) profiling to assess the mechanism(s) by which EVs released from ECs exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies activated unstimulated ECs.

Results and conclusions

Anti-β2GPI antibodies caused formation of an EC inflammasome and the release of EVs that were enriched in mature IL-1β, had a distinct miRNA profile, and caused endothelial activation. However, activation was not inhibited by an IL-1β antibody, an IL-1 receptor antagonist, or IL-1 receptor siRNA. EC activation by EVs required IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 phosphorylation, and was inhibited by pretreatment of cells with TLR7 siRNA or RNase A, which degrades ssRNA. Profiling of miRNA in EVs released from ECs incubated with β2GPI and either control IgG or anti-β2GPI antibodies revealed numerous differences in the content of specific miRNAs, including a significant decrease in mIR126. These observations demonstrate that, although anti-β2GPI-derived endothelial EVs contain IL-1β, they activate unstimulated ECs through a TLR7-dependent and ssRNA-dependent pathway. Alterations in miRNA content may contribute to the ability of EVs derived from ECs exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies to activate unstimulated ECs in an autocrine or paracrine manner.

Keywords: antiphospholipid antibodies, cell-derived microparticles, endothelial cells, exosomes, interleukins, Toll-like receptors

Introduction

The antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by thrombosis and/or recurrent fetal loss in the presence of persistently elevated antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs) [1,2]. Most pathologic APLAs are directed against β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), a phospholipid-binding protein [3–5]. One mechanism by which APLAs may promote thrombosis is by activating endothelial cells (ECs) [6–8]. Expression of proinflammatory cytokines as a consequence of EC activation in response to APLAs [9] may contribute to the prothrombotic phenotype [10].

Another consequence of EC activation by APLAs is the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) [11], a term encompassing both ‘microparticles’ (> 100 nm in diameter) and exosomes (< 100 nM in diameter) [12,13]. EC-derived EVs circulate at elevated concentrations in patients with inflammatory vascular syndromes [14,15], cancer [16,17], and APS [18–21]. EVs express procoagulant activity through tissue factor (TF) and anionic phospholipid on the vesicle surface [22–24]. Moreover, EVs may transfer biologically active molecules, including mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and proteins, among cells, facilitating intracellular communication and altering the recipient cell phenotype [13,25–28]. For example, EVs from lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated platelets [29] or monocytes [30] contain interleukin (IL)-1β and activate ECs through the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R). Platelet-derived EVs from synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis also contain IL-1β, and stimulate inflammatory responses in synovial fibroblasts [31]. However, the repertoire of proteins and nucleic acids associated with EVs is complex, and varies according to the origin of the EVs and the stimulus for release. The response of recipient cells depends, in turn, on their receptor expression profile [32,33].

As anti-β2GPI antibodies contribute to APLA-associated thrombosis through activation of ECs [34], we hypothesized that EVs released as a consequence of EC activation might have unique properties and induce activation of unstimulated ECs and perhaps other cell types in an autocrine/paracrine manner. We report that anti-β2GPI antibodies induce EC inflammasome formation, leading to the release of EVs enriched in active IL-1β that activate unstimulated ECs. However, activation is not mediated by IL-1β, but occurs in a Toll-like receptor (TLR)7-dependent and ssRNA-dependent manner, owing, at least in part, to the content of specific miRNAs in EVs.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human β2GPI was purified from fresh frozen plasma [35]. Anti-β2GPI antibodies were affinity-purified from sera of rabbits immunized with human β2GPI and two patients with APS by the use of β2GPI conjugated to AffiGel HZ (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) [35]; purity of the affinity-purified antibodies was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies bound to β2GPI-coated microplates, whereas IgG that fell through the column did not (Fig. S1). Purified β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies were incubated with Detoxi-Gel (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) to remove residual endotoxin, and were confirmed to have endotoxin levels of < 15 EU mg−1 protein with the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Pierce). LPS (O55:B5), bovine serum albumin (BSA), dimethylsulfoxide, AC-YVAD-CMK and mAbs against γ-actin were from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). IL-1β was from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Indicator-free medium 199 was from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Recombinant human IL-1R antagonist and mouse and goat polyclonal antibodies against IL-1β were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). PAM3CSK4 (TLR2 ligand), R837 (Immiquimod; TLR7 ligand) and ODN 2006 (TLR9 ligand) were from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA). RNase A was from Roche (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Control rabbit and human IgG and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Antibodies against β-actin, phospho-IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) (Thr345-Ser346), TLR2, TLR7 and TLR9 were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against NLRP3 were from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Antibodies against ASC, E-selectin, caspase-1, IRAK4 and TLR4 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies against human TF (#4508CJ) were from Sekisui Diagnostics (Lexington, MA, USA). SuperSignal West Femto substrate was from Pierce, and SureBlue Reserve 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate was from KPL (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Life Technologies. Dynasore, an inhibitor of dynamin-dependent endocytosis, was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA) [36].

Patients

The results of all studies were confirmed by the use of affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies from two patients with APS. Patient 1 was a 50-year-old woman with a history of two deep venous thrombotic events and a pulmonary embolism. Because of recurrent events while she was receiving warfarin, she had been maintained on enoxaparin for 10 years. Her antiphospholipid testing revealed positivity for lupus anticoagulant, an anti-β2GPI IgG level of 45 units, and an anticardiolipin IgG level of 40 GPL units. Patient 2 was a 48-year-old man with a history of multiple deep venous thrombi and a stroke. He had been maintained on fondaparinux, aspirin and clopidogrel after experiencing recurrent events while receiving warfarin and enoxaparin. His antiphospholipid testing revealed positivity for lupus anticoagulant, an anti-β2GPI IgG level of 54 units, and an anticardiolipin IgG level of 58 GPL units. Patients provided written informed consent prior to donation of blood, and all studies were approved by the institutional review board of the Cleveland Clinic and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ECs

Human umbilical vein ECs were cultured as previously described [37]. Cells were maintained in medium 199 containing 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 30 μg mL−1 endothelial mitogen (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA, USA), 100 U mL−1 penicillin, and 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin. All experiments were performed with cells of passage 3 or lower.

Isolation of endothelial EVs and EV RNA

ECs (2 × 106)were seeded in 10-cm gelatin-coated tissue culture plates. Cells were incubated in serum-free medium 199 containing 1% BSA for 2 h, and conditioned medium was collected for EV analysis after further incubation of cells with β2GPI (300 nM) and either control IgG or anti-β2GPI antibodies (600 nM) for 6 h, as in our previous studies [11]. For isolation of EVs, conditioned medium was centrifuged at 2500 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was centrifuged at 13 000 × g for 2 min [19,38]. EVs were isolated from the supernatant of the second centrifugation by centrifugation for 90 min at 100 000 × g.

EV RNA was isolated after washing of EVs in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifugation at 100 000 × g for 90 min. EVs were then resuspended in 700 μL of QIAzol lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Total RNA was isolated with the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). Quantification of EV RNA was performed with an RNA Pico Chip on an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Bio-Rad). RNA library construction and next-generation sequencing were performed at SeqMatic (Fremont, CA, USA).

Assessment of EC activation

EC activation was assessed by measuring E-selectin cell surface expression by ELISA [11,35]. In selected experiments, ECs were incubated with Dynasore for 30 min prior to addition of anti-β2GPI antibodies. As previously reported, affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies activated ECs only in the presence of β2GPI in an F(ab′)2-dependent manner [35]. IgG that did not bind to the β2GPI affinity column did not activate ECs in the absence or presence of β2GPI, even when used at a 100-fold higher concentration than the affinity-purified antibodies (Fig. S1).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

First-strand cDNA synthesis from isolated EC RNA was performed with the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The reverse transcription reaction product (10–20 ng) was used for qPCR with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were conducted and analyzed with the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression was calculated according to the comparative (2−ΔΔCT) method, with the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene as the reference gene for normalization. Sequences of qPCR primers are listed in Table S1.

Immunoblotting

ECs were washed with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium fluoride, and protease inhibitors (Roche). Nuclei and cellular debris were removed by centrifugation (12 000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C). Cell or EV extracts, or EV-free conditioned medium, were mixed with SDS sample buffer and heated at 95 °C for 5 min before separation by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes and incubated with primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected with SuperSignal West Femto substrate.

Inflammasome staining

Confluent monolayers of ECs on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips were incubated with β2GPI and control or anti-β2GPI antibodies. Cells were fixed by incubation in PBS containing 3.7% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked in PBS containing 5% normal donkey serum and 1% BSA before incubation with primary antibodies against ASC and caspase 1. After washing, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies. Cells were mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) to stain nuclei prior to imaging with a Leica confocal microscope (Allendale, NJ) with a × 63 oil immersion objective.

RNA-mediated interference

ECs were treated with scrambled RNA (control) or small interfering RNA (siRNA) pools targeting human IRAK4, IL-1R inhibitor, TLR2, TLR4, TLR7, or TLR9 (Dharmacon, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). siRNAs were used at concentrations of 50–100 nM, and delivered to ECs by the use of X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche). The efficiency of siRNA-mediated knockdown was assessed by immunoblotting of target proteins and assessment of mRNA expression by qPCR [11].

RNase A treatment of EVs

EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation were resuspended in nuclease-free PBS, and treated with 100 μg mL−1 RNase A at 37 °C for 30 min. EVs were washed in PBS prior to use.

Bioinformatic analysis

Small RNA reads were aligned to the human reference genome GRCH37.75 by use of STAR ALIGNER version 2.3.1z1, with parameter settings appropriate for small RNA. Approximately 130 000 reads were uniquely mapped per sample. Gene counts were generated from the aligned reads without multiple mappings by the use of FEATURECOUNTS version 1.4.4 and gene definitions from Ensembl 75. Sixty-eight per cent of the gene-mapped reads fell in miRNAs and 10% in long intervening non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs). Genes with reads per kilobase per million reads measures of < 0.5 in all of the samples were dropped, leaving 5817 genes for analysis. The filtered genes included 283 miRNAs, 241 lincRNAs, and 4360 protein-coding genes. Differential gene expression was performed in R version 3.0.2 with the voom approach [39] as implemented in the R package LIMMA version 3.18.13. The false discovery rate was used to control for multiple testing.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All experimental data was generated in triplicate, and experiments were repeated at least three times. Experimental results were compared by use of the Student two-tailed t-test for unpaired samples. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

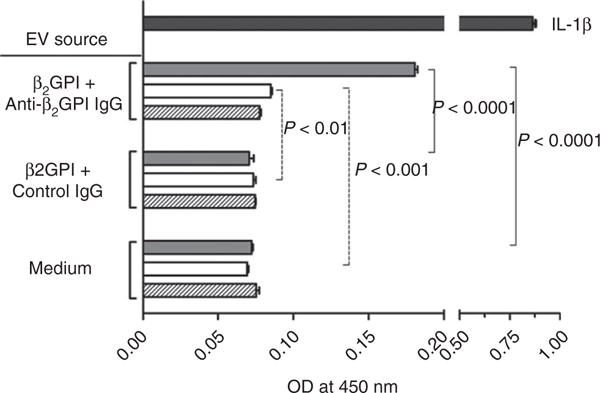

EVs released in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies activate ECs

Although we and others have reported that anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate the release of EVs from ECs, whether these EVs activate ECs or other cell types has not been assessed. We analyzed the ability of EVs from ECs incubated in medium alone, with β2GPI and control rabbit IgG or with β2GPI and rabbit anti-β2GPI antibodies to activate unstimulated ECs. As shown in Fig. 1, only EVs from ECs exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies activated unstimulated ECs. As compared with EVs from ECs incubated with control IgG, EVs from ECs treated with anti-β2GPI antibodies caused 20% and 150% increases in cell surface E-selectin, respectively, at EV donor cell/recipient cell ratios of 4 : 1 and 20 : 1.

Fig. 1.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) released in response to anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies activate unstimulated endothelial cells (ECs). ECs were cultured for 6 h in the presence of medium alone, β2GPI and control rabbit IgG, or β2GPI and rabbit anti-β2GPI antibodies. EVs were isolated from conditioned medium and incubated with unstimulated ECs at three different ratios of donor cells (from which the EVs were derived) to recipient cells (0.8 : 1, 4 : 1, and 20 : 1; represented by hatched, open and gray bars, respectively), for 6 h. EC activation was measured by the expression of E-selectin on the cell surface following incubation with EVs. OD450 nm values from triplicate points from a single experiment representative of three experiments performed are depicted. The upper bar represents the endothelial response to purified interleukin (IL)-1β (50 pg mL−1). EVs from anti-β2GPI-treated cells caused a concentration-dependent increase in E-selectin expression.

To assess whether EVs from ECs treated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies activated unstimulated ECs through carryover of β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies, these EVs were analyzed by immunoblotting. Lysates derived from amounts of EVs equal to those used to activate ECs contained only trace amounts of β2GPI and did not contain detectable IgG (Fig. S2).

EVs released in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies are enriched in active IL-1β

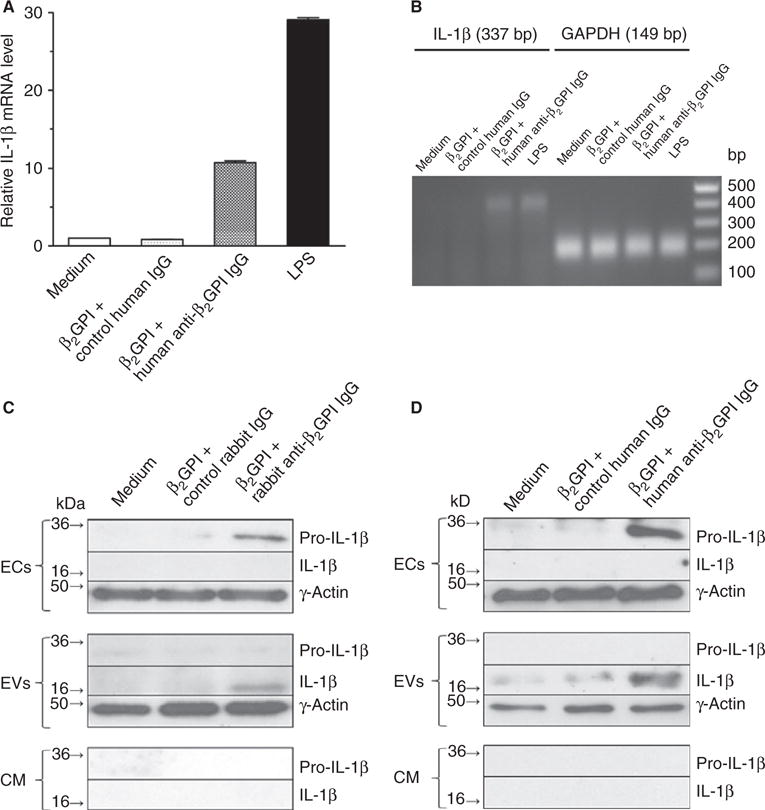

One mechanism by which APLA-derived EVs might activate ECs is by delivering IL-1β to endothelial IL-1R. As shown in Fig. 2A, anti-β2GPI antibodies caused a 12-fold increase in EC IL-1β mRNA expression, as confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis of the 337 nucleotide qPCR product (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies stimulate interleukin (IL)-1β mRNA expression in endothelial cells (ECs), accompanied by release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) enriched in active IL-1β. (A) ECs were incubated with medium alone, β2GPI and control human or rabbit IgG, or β2GPI and affinity-purified rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies, as described in Materials and methods. Cells were then harvested, and the content of IL-1β mRNA was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). (B) Analysis of the 337 nucleotide IL-1β qPCR products with 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. (C, D) Immunoblot analysis of IL-1β in ECs, isolated EVs and EV-free conditioned medium (CM) following incubation of ECs with medium, control IgG, or affinity-purified rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies. Increased amounts of pro-IL-1β were present in treated cells, but only the cleaved, active form of IL-1β was present in EVs. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

ECs incubated with either affinity-purified rabbit (Fig. 2C) or human (Fig. 2D) anti-β2GPI antibodies also contained increased amounts of pro-IL-1β, but did not contain the active, cleaved form of IL-1β. In contrast, EVs from these cells contained only active, cleaved IL-1β. Neither species of IL-1β was detected in EV-free conditioned medium. These data suggest that active IL-1β is released in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies through packaging in EVs.

Anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate formation of an EC inflammasome

To determine the mechanism by which EC pro-IL-1β is converted to mature IL-1β and released in EVs, we determined whether anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulated the formation of inflammasomes, and whether EVs from these cells contained inflammasome components. Both intact ECs and EVs released in response to rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies contained the key inflammasome components ASC, NLRP3, and pro-caspase 1 (Fig. 3A and B); moreover, EVs were enriched in these components relative to the cells from which they were released. Active caspase 1 (P20) was only observed in EVs from anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells (Fig. 3A,B), consistent with our finding that these EVs contained mature IL-1β (Fig. 2C,D).

Fig. 3.

Inflammasome assembly in anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibody-treated endothelial cells (ECs). (A, B). Immunoblot analysis of ASC, NLRP3 and caspase 1 in extracts of ECs treated with medium, β2GPI and control IgG, or β2GPI and affinity-purified rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies, as well in extracts of extracellular vesicles (EVs) from the treated cells. All three inflammasome components are present in extracts of intact ECs and EVs, although active caspase 1 (p20) was present only in EVs. (C) Confocal microscopy of ECs treated with human anti-β2GPI antibodies as in (B) and stained with antibodies against ASC (red) and caspase 1 (green). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). Note the assembly of inflammasomes that costain for ASC and caspase 1 in anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells (inserts).

Staining of cells treated with medium, β2GPI and control human IgG or β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG for ASC and caspase 1 showed formation of inflammasomes only in anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells (Fig. 3C).

To define the role of the inflammasome in regulating the properties of EVs, ECs were pretreated with Ac-YVAD-CMK, an irreversible inhibitor of caspase 1, before being incubated with medium, β2GPI and control human IgG or β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG. As shown in Fig. S3A, Ac-YVAD-CMK did not affect the ability of human anti-β2GPI IgG to induce pro-IL-1β expression in ECs. However, Ac-YVAD-CMK inhibited pro-IL-1β cleavage in EVs induced by human anti-β2GPI IgG.

Recent work by Rothmeier et al. demonstrated that activation of a calpain/caspase-dependent pathway facilitates the release of TF from cytoskeletal filamin in monocytes exposed to ADP and LPS [40]. Pretreatment of ECs with Ac-YVAD-CMK resulted in slight inhibition of TF expression, as assessed with an Apogee flow cytometer, on EVs released following incubation with β2GPI and control human IgG (884 EVs μL−1 with vehicle as compared with 679 EVs μL−1 with Ac-YVAD-CMK; 23.2% reduction; Fig. S3B). However, TF expression on EVs induced by β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI antibodies was not affected by Ac-YVAD-CMK (1393 EVs μL−1 with vehicle as compared with 1434 EVs μL−1 with Ac-YVAD-CMK). These differences may reflect activation of different signaling pathways by ADP and LPS than by anti-β2GPI antibodies, or differences in the mechanisms of EV and TF release between cell types.

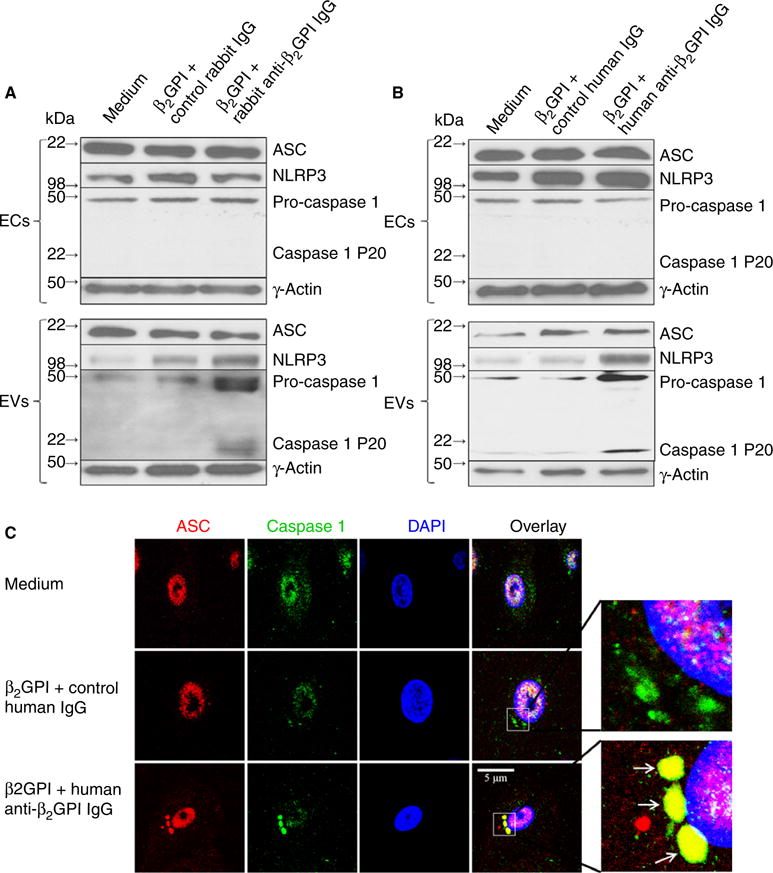

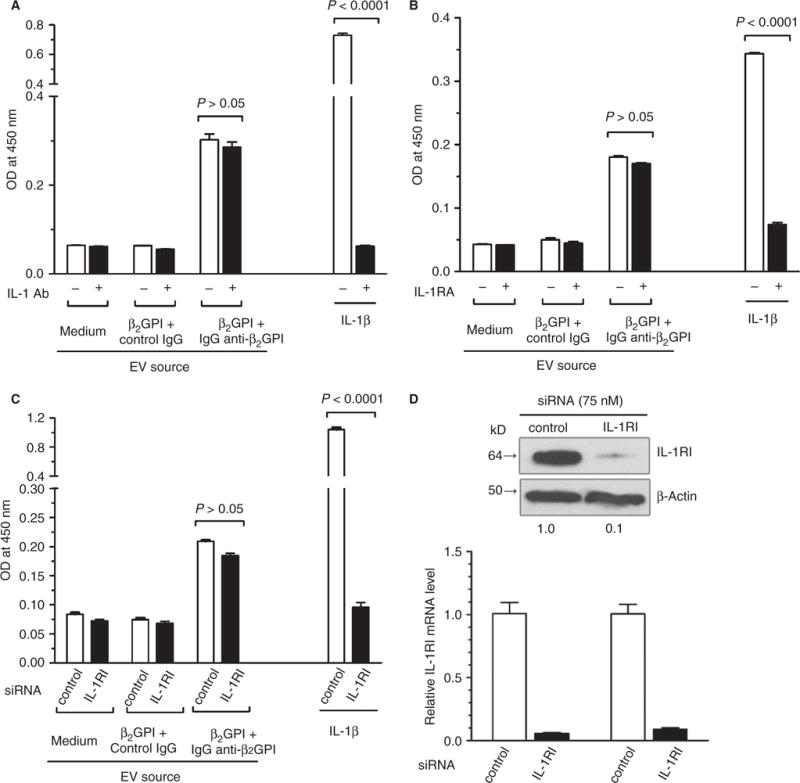

EC activation by EVs released in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies is not mediated by IL-1β

To determine the role of IL-1β in the activation of ECs by EVs, we assessed the effect of a neutralizing antibody against IL-1β (0.1 μg mL−1), a peptide IL-1R antagonist (Kineret, 200 ng mL−1) or IL-1R siRNA (75 nM) on cellular activation by EVs. As shown in Fig. 4A–C, these inhibitors blocked the EC response to IL-1β by 99.9%, 90.8%, and 97.5%, respectively, but did not inhibit cellular activation by EVs. Immunoblotting and qPCR confirmed that siRNA decreased the expression of IL-1R mRNA and protein by ~ 90% (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Activation of endothelial cells (ECs) by anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibody-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) is not interleukin (IL)-1β-dependent. EVs were isolated from ECs incubated in medium alone, with β2GPI and control IgG, or with β2GPI and affinity-purified human anti-β2GPI IgG, and then incubated with unstimulated ECs as in Fig. 1. (A–C) Incubations were performed in the absence or presence of a neutralizing IL-1 antibody (IL-1 Ab) (A), in the absence or presence of a peptide IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) antagonist (IL-1RA), and with ECs pretreated with IL-1R or control, scrambled small interfering RNA (siRNA) (C). Cells were also treated with recombinant IL-1β as a positive control. The IL-1β antibody or IL-1R inhibitors (IL-1RIs) blocked activation in response to IL-1β, but not in response to EVs. (D) Immunoblot of IL-1R after siRNA pretreatment of ECs, demonstrating > 90% knockdown.

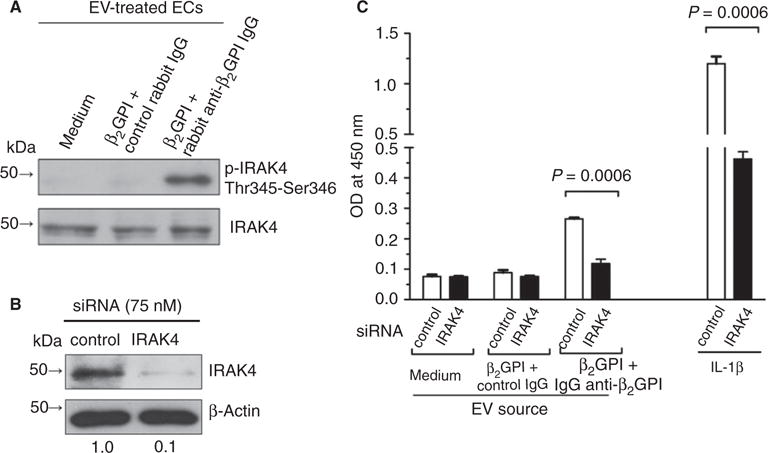

EVs from anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells activate the TLR–IL-1R (TIR) pathway

Although IL-1R inhibition did not block EC activation by EVs, we examined the involvement of the TIR pathway by assessing EV-induced phosphorylation of IRAK4, a component of the TIR signaling pathway downstream of all TLRs and IL-1R. As shown in Fig. 5A, we observed IRAK4 phosphorylation in ECs exposed to EVs from cells treated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies, but not those exposed to EVs from cells treated with β2GPI and control IgG.

Fig. 5.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) from anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibody-treated endothelial cells (ECs) stimulate interleukin (IL)-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) phosphorylation. (A) Unstimulated ECs were incubated with EVs from cells incubated in medium alone, with β2GPI and control IgG, or with β2GPI and affinity-purified human anti-β2GPI antibodies. Cell extracts were then prepared and analyzed for IRAK4 phosphorylation by immunoblotting with antibodies against phospho-IRAK4 (Thr345-Ser346; upper panel) or total IRAK4. (B) IRAK4 expression in ECs treated with IRAK4 small interfering RNA (siRNA). (C) IRAK4 siRNA blocks EC activation induced by EVs from β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells, and in response to IL-1β, used as a positive control.

To further define the role of the TIR pathway in EV-induced EC activation, we used siRNA to inhibit IRAK4 expression prior to treatment of unstimulated cells with EVs from β2GPI-treated and anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells (Fig. 5B). IRAK4 siRNA inhibited EV-induced EC activation by 77% (Fig. 5C).

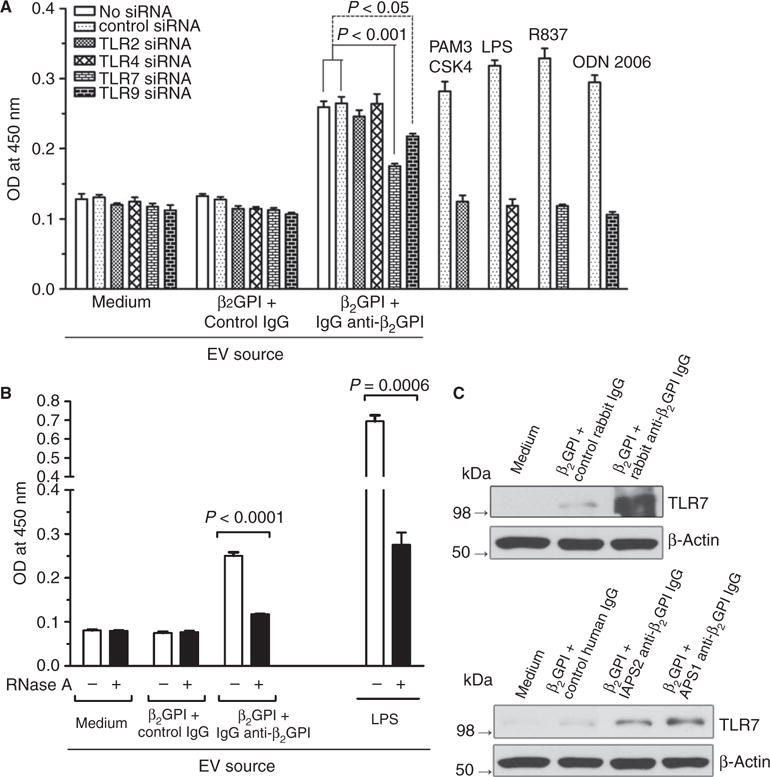

EC activation by EVs from anti-β2GPI IgG-treated cells involves an ssRNA-dependent and TLR7-dependent pathway

As EV-induced EC activation occurred through a TIR-mediated pathway but was not IL-1R-dependent, we considered the roles of other receptors that mediate TIR-dependent activation, or that have been implicated in the activation of monocytes by APLAs, specifically TLR2, TLR4, TLR7, and TLR9 [41–43]. Treatment of ECs with siRNAs against each of these reduced expression of their target protein by > 85% (Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 6A, whereas each of these siRNAs blocked EC activation in response to its cognate ligand (TLR2, PAM3CSK4; TLR4, LPS; TLR7, R837; TLR9, ODN 2006), only inhibition of TLR7 and TLR9 expression inhibited E-selectin expression in response to EVs (P = 0.0009 and P = 0.01, respectively). However, TLR9 siRNA caused a mild reduction in TLR7 protein expression (Fig. S4), which probably explains the inhibitory effect.

Fig. 6.

Anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI)-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) activate endothelial cells (ECs) through a Toll-like receptor (TLR)7-dependent and ssRNA-dependent pathway. (A) Effect of small interfering RNA (siRNA) against TLR2, TLR4, TLR7 or TLR9 on EC activation induced by EVs, assessed by measurement of cell surface E-selectin. TLR7 siRNA was the most potent in inhibiting activation, reducing the extent of activation by ~ 70%. Activation of cells by specific TLR agonists was suppressed by the appropriate siRNAs. (B) Pretreatment of EVs with RNase A blocked activation of ECs induced by anti-β2GPI-derived EVs by ~ 80%; inhibition of activation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-derived EVs was also noted. (C) Effect of anti-β2GPI antibodies on EC TLR expression. TLR7 is expressed at a low level on unstimulated ECs; however, both rabbit anti-β2GPI antibodies (upper panel) and affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies from two patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (lower panel) caused significantly increased expression of TLR7.

TLR7 is activated in response to ssRNA [44,45], including miRNAs in some cell types [46–48]. To test whether RNA may contribute to cellular activation by EVs from anti-β2GPI treated cells, we preincubated EVs with RNase A. EVs were washed after RNase A treatment to remove free enzyme. RNase A reduced the amount of small RNA associated with EVs, although larger RNA species associated with EV were less affected (Fig. S5). Pretreatment of EVs with RNase A inhibited their ability to activate unstimulated ECs by 80% (P < 0.0001; Fig. 6B).

Comparison of RNA isolated from EVs from cells exposed to β2GPI and control IgG with RNA isolated from EVs from cells exposed to β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies with a bioanalyzer demonstrated similar RNA amount and size (Fig. S5). However, the observations that only EVs from cells exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulated EC activation and that activation was inhibited by pretreatment of EVs with RNase A suggested differences in the specific RNA content of EVs released in response to control IgG or anti-β2GPI antibodies. We therefore analyzed miRNA profiles of EV RNA. Significant differences in the quantities of 18 miR-NAs associated with EVs from the two sources were observed, with 12 miRNAs being upregulated and six being downregulated (Table 1). Of miRNAs with known functions in ECs, the amount of miR126, which inhibits VCAM-1 expression [49], was decreased by 18% in EVs from anti-β2GPI-treated cells (P < 6.5 × 106).

Table 1.

Top 10 differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs) in extracellular vesicles derived from endothelial cells treated with control IgG or anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies

| miRNA | Fold change (APS/control IgG) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| mIR 126 | 0.82 | 6.51 × 10−6 |

| mIR100 | 1.35 | 0.000157 |

| mIR 1185-1 | 9.40 | 0.000634 |

| mIR10b | 1.16 | 0.00187 |

| mIR576 | 7.22 | 0.00462 |

| mIR1251 | 6.39 | 0.00679 |

| mIR543 | 0.22 | 0.011 |

| mIR26A1 | 5.15 | 0.020 |

| mIR32 | 4.87 | 0.022 |

| mIR365b | 0.19 | 0.031 |

| mIR339 | 0.41 | 0.034 |

APS, antiphospholipid syndrome.

Anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate TLR7 expression and redistribution in ECS

In unstimulated ECs, TLR7 is expressed at very low levels (Fig. 6C). However, increased expression of TLR7 following interactions of ECs with anti-β2GPI antibodies might promote sensitivity to TLR7 ligands. The expression of TLR7 was increased following exposure of cells to β2GPI in the presence of both rabbit and human anti-β2GPI antibodies, whereas control IgG had no effect (Fig. 6C). Examination of anti-β2GPI-treated ECs by confocal microscopy confirmed an increase in the expression of TLR7 and suggested redistribution towards the cell periphery; however, the limited resolution did not allow us to definitively determine whether TLR7 was redistributed to the endosomes, as described by Prinz et al. in monocytes [41], transiently expressed on the cell surface, or localized to another cellular compartment. We observed increased labeling of endothelial TLR7 with sulfo-NHS-LC biotin, a cell-impermeable biotinylation reagent [50], following exposure of cells to anti-β2GPI antibodies, suggesting enhanced accessibility to extracellular ligands (Fig. S6).

Discussion

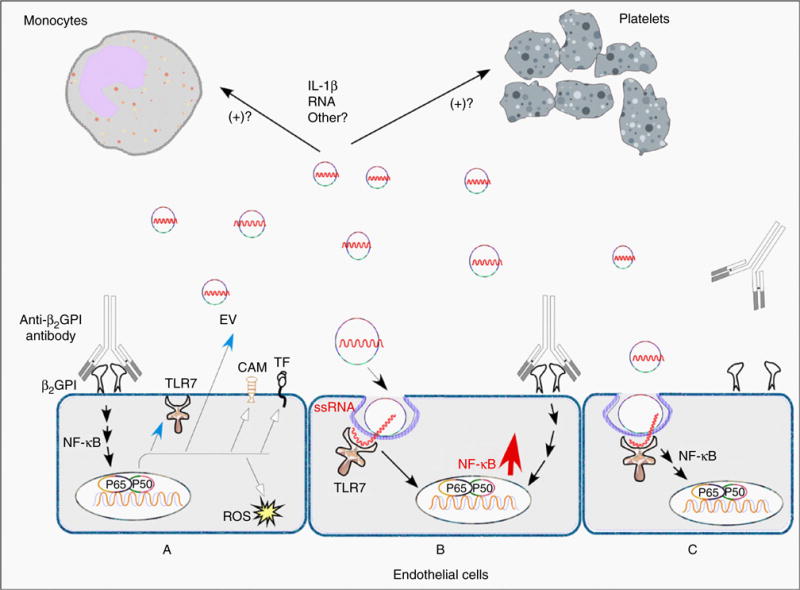

Elevated levels of EVs circulate in inflammatory vascular disorders [14,15], including APS [18–21]. These EVs may stimulate thrombosis through expression of TF and exposure of anionic phospholipid [18,19,21,51]. Although EVs may directly support the initiation of thrombi, another potential mechanism by which they stimulate thrombosis may be their ability to promote vascular dysfunction through interactions with vascular cells in an autocrine/paracrine manner (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Model for extracellular vesicle (EV)-induced endothelial cell (EC) activation in antiphospholipid syndrome. Depicted are three ECs. In (A), cells are activated by binding of β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) to the cell surface, followed by crosslinking of bound β2GPI by anti-β2GPI antibodies. This initiates cellular activation, occurring primarily through a nuclear factor-jB (NF-jB)-dependent pathway, leading to increased expression of proinflammatory and procoagulant genes such as those encoding tissue factor (TF) and cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). Toll-like receptor (TLR)7 remains in an intracellular compartment distinct from the endosome prior to cellular activation, but its expression is increased by anti-β2GPI antibodies, as is the elaboration of EVs. In (B), neighboring cells are activated concurrently in a paracrine manner through parallel, converging pathways by anti-β2GPI antibodies and EVs, leading to more pronounced NF-jB activation. In (C), cells are activated, perhaps less vigorously, by EVs alone, which may potentially sensitize them to further activation mediated by anti-β2GPI antibodies. We hypothesize that TLR7 is translocated to endosomes following activation of ECs by anti-β2GPI antibodies, and may transiently become exposed to extracellular ligands, although this requires confirmation. IL, interleukin; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Our study demonstrates that anti-β2GPI antibodies induce the formation of an EC inflammasome, leading to the release of EVs enriched in active IL-1β and containing inflammasome components. EVs released in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies activate unstimulated ECs, whereas those from cells incubated in medium alone or with control IgG do not. However, the ability of IL-1β-containing EVs to activate ECs was not dependent on IL-1R. Hence, our results contrast with those of Wang et al., who observed activation of ECs by LPS-derived monocyte EVs [30], and Brown et al., who reported activation of resting platelets by EVs from LPS-stimulated platelets [29]. The inability of EVs to activate cells through IL-1R-dependent mechanisms probably reflects the presence of IL-1R protein associated with EVs (Fig. S7).

Despite the lack of an essential role for IL-1β in cell activation, we demonstrated involvement of the TIR signaling pathway, finding that IRAK4 is phosphorylated following exposure of ECs to anti-β2GPI antibody-derived EVs. Subsequent studies employing siRNA-mediated knockdown of individual endothelial TIR family members demonstrated specific inhibition of EV-induced endothelial activation by TLR7 siRNA. A role of TLR7, a receptor for ssRNA, including some miRNAs [46,47], was further suggested by the observation that pretreatment of EVs with RNase A blocks their ability to activate ECs.

Bioanalyzer analyses of EV before and after digestion with RNase A (Fig. S5) suggest that most of the EV-associated RNA was miRNA. The presence of miRNA in association with EVs from cells exposed to control IgG or anti-β2GPI antibodies, and the equal susceptibility to RNase A on both types of EV, suggest that miRNA associated with anti-β2GPI antibody-derived EVs differs from that associated with EVs from cells exposed to control IgG, and may therefore interact with TLR7 in a specific manner. Profiling of EV-associated RNA demonstrated substantial differences in the miRNAs contained within EVs released by cells exposed to control IgG and cells exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies. For example, the expression of mIR126, which inhibits the expression of VCAM-1 in response to inflammatory stimuli [49], was decreased by 18% in EVs from cells exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies. However, the observation that RNase A treatment of EVs inhibited their ability to activate cells suggests that other miRNAs contribute directly to endothelial activation. Unfortunately, other than mIR126, there is no information available concerning the functions of the other miRNAs identified, particularly with regard to ECs. However, miRNAs are important modulators of TLR signaling [48], and much remains to be learned in terms of the effects of individual miRNAs on the functions of TLRs.

miRNA is thought to be contained within EVs [13,52], although, in our studies, susceptibility to RNase A digestion suggests that at least some miRNA was surface-accessible. Argonaute2 complexes with miRNA have been identified independently of vesicles in plasma [53], and we have observed argonaute2 on plasma EVs by the use of flow cytometry. Hence, cellular activation by EVs might be initiated by direct interactions of EV-associated miRNA with TLR7, or by endocytosis of EVs followed by release of miRNA and downstream effects on intracellular signaling. The delay of 4–6 h for cellular activation to occur following exposure to EVs, and the inhibition of cellular activation by dynasore (Fig. S8), are consistent with internalization of EVs and signaling within endosomes. The exact site to which TLR7 is redistributed following treatment of cells with anti-β2GPI antibodies is uncertain, although additional studies to define this site are in progress.

We hypothesize that anti-β2GPI antibodies and EVs contribute to cellular activation in an additive or synergistic manner. Anti-β2GPI antibodies may partially activate cells, increasing the expression of TLR7, which promotes additional interactions with EVs, leading to further EC dysfunction. It is also possible that EVs may prime unstimulated ECs for activation by anti-β2GPI antibodies. The ability of sulfo-NHS-LC biotin to label TLR7 on unstimulated ECs suggests that some TLR7 is available in a surface-accessible compartment even prior to EC activation.

In summary, we have demonstrated that EVs released from ECs stimulated with anti-β2GPI antibodies activate unstimulated ECs. These EVs may work with anti-β2GPI antibodies to promote the development of vascular inflammation. At least one mechanism by which EVs induce cellular activation is through presentation of ssRNA, most likely miRNA, to TLR7. Additional studies will be required to further characterize EVs in patients with APS and their importance in APS pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. (A) Binding of affinity-purified anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies and fall through from the β2GPI affinity columns to β2GPI by ELISA (EL, column eluate; FT, flow-through). (B) Binding of affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies and fall through from the β2GPI affinity columns to cardiolipin in a standard anticardiolipin antibody assay in which plates were blocked with bovine serum. (C) Activation of endothelial cells (assessed by measurement of cell surface E-selectin expression) by control human IgG and the anti-β2GPI IgG from patient APS1 in the absence or presence of β2GPI. (D) Activation of endothelial cells by the non-β2GPI-reactive fall through IgG from patient APS1.

Fig. S2. Negligible amounts of β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) and anti-β2GPI IgG are adsorbed to extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs were isolated from endothelial cells treated with medium, β2GPI and control human IgG, β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Lysates prepared from quantities of EVs identical to those used for assessment of endothelial cell activation were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Known amounts of purified human IgG or β2GPI were used as standards (left lanes). In routine cell activation assays with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI IgG, we use ~ 1.6 μg of β2GPI and ~ 9 μg of anti-β2GPI IgG.

Fig. S3. Effect of Ac-YVAD-CMK on interleukin (IL)-1β and tissue factor (TF) expression in extracellular vesicles (EVs) from endothelial cells treated with anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies. Endothelial cells (ECs) were pretreated with Ac-YVAD-CMK (5 and 10 μM in Fig. 1A, and 5 μM in Fig. 1B) for 1 h before incubation with medium, β2GPI, and control human IgG, or β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG. EVs were isolated and analyzed for IL-1β expression by immunoblotting or labeled with FITC–conjugated control mouse IgG or FITC-conjugated antibodies against TF before analysis on an Apogee flow cytometer.

Fig. S4. (A) Reduction in target proteins following treatment of endothelial cells with siRNA against THR2, TLR7, or TLR9. (B) Reductions in endothelial cell TLR4 by different concentrations of TLR4 siRNA.

Fig. S5. RNase A digestion of extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs were isolated from endothelial cells treated with medium, β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), and control human IgG, β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). EVs were then digested with RNase A (100 μg mL−1) at 37 °C for 30 min, and this was followed by two washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). RNA was extracted from EVs with a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and run on a PicoChip. The figure demonstrates digestion of the majority of the small RNA while larger bands (arrows) remain relatively intact, suggesting that the RNase A did not freely permeate the EVs.

Fig. S6. Analysis of Toll-like receptor (TLR)7 expression on endothelial cells treated with anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI antibodies. (A) Endothelial cell surface-accessible proteins were labeled with sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin at 4 °C for 10 min. After preparation of the cell lysate, biotinylated proteins were pulled down with streptavidin beads. The pulled-down proteins were analyzed by western blotting for CD31 and β-actin expression. (B) Endothelial cells were treated with medium, β2GPI and control human IgG, or β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG. Cell surface proteins were labeled and pulled down as in (A). The pulled-down proteins were then analyzed by immunoblotting for TLR7, CD31, and β-actin expression.

Fig. S7. Immunoblot of extracellular vesicle (EV) extracts for interleukin-1 receptor type I (IL-1RI).

Fig. S8. Activation of endothelial cells by extracellular vesicles (EVs) from a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is inhibited by dynasore. EVs from serum of one healthy control subject, or one APS patient was isolated by serial centrifugation, and then added to endothelial cells in a 96-well plate. Before addition of the EVs, endothelial cells were pretreated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or dynasore (50 μM). Each well was then incubated for 8 h with either medium alone or EVs from 100 μL of serum. Treated endothelial cells were assayed for cell surface E-selectin expression as described in Materials and methods. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Table S1. Primers used in interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH P50 HL081011 (KRM project leader) and an American Society of Hematology bridge grant.

Footnotes

Addendum

M. Wu and K. R. McCrae conceived the project and designed the experiments. M. Wu and K. R. McCrae wrote the manuscript. M. Wu and S. Kundu performed the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed to its submission.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

References

- 1.Rand JH. The antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007:136–42. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, Derksen RH, De Groot PG, Koike T, Meroni PL, Reber G, Shoenfeld Y, Tincani A, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Krilis SA. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNeil HP, Simpson RJ, Chesterman CN, Krilis SA. Anti-phospholipid antibodies are directed against a complex antigen that includes a lipid-binding inhibitor of coagulation: b2-glycoprotein I (apolipoprotein H) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4120–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuura E, Igarashi Y, Fujimoto M, Ichikawa K, Koike T. Anticardiolipin cofactor(s) and differential diagnosis of autoimmune disease. Lancet. 1990;335:177–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galli M, Comfurius P, Maassen C, Hemker HC, De Baets MH, van Breda-Vriesman PJC, Barbui T, Zwaal RFA, Bevers EM. Anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) directed not to cardiolipin but to a plasma cofactor. Lancet. 1990;335:1554–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91374-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannakopoulos B, Passam F, Rahgozar S, Krilis SA. Current concepts on the pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood. 2007;109:422–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-001206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Crowther M, Branch W, Khamashta MA. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Lancet. 2010;376:1498–509. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60709-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palomo I, Segovia F, Ortega C, Pierangeli S. Antiphospholipid syndrome: a comprehensive review of a complex and multisystemic disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:668–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamid C, Norgate K, D’Cruz DP, Khamashta MA, Arno M, Pearson JD, Frampton G, Murphy JJ. Anti-beta2GPI-antibody-induced endothelial cell gene expression profiling reveals induction of novel pro-inflammatory genes potentially involved in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1000–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.063909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qamar A, Rader DJ. Effect of interleukin 1beta inhibition in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23:548–53. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328359b0a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betapudi V, Lominadze G, Hsi L, Willard B, Wu M, McCrae KR. Anti-beta2GPI antibodies stimulate endothelial cell microparticle release via a nonmuscle myosin II motor protein-dependent pathway. Blood. 2013;122:3808–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Pol E, Boing AN, Harrison P, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:676–705. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gyorgy B, Szabo TG, Pasztoi M, Pal Z, Misjak P, Aradi B, Laszlo V, Pallinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, Nagy G, Falus A, Buzas EI. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2667–88. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viera AJ, Mooberry M, Key NS. Microparticles in cardiovascular disease pathophysiology and outcomes. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:243–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leroyer AS, Anfosso F, Lacroix R, Sabatier F, Simoncini S, Njock SM, Jourde N, Brunet P, Camoin-Jau L, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Endothelial-derived microparticles: biological conveyors at the crossroad of inflammation, thrombosis and angiogenesis. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:456–63. doi: 10.1160/TH10-02-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwicker JI, Liebman HA, Bauer KA, Caughey T, Campigotto F, Rosovsky R, Mantha S, Kessler CM, Eneman J, Raghavan V, Lenz HJ, Bullock A, Buchbinder E, Neuberg D, Furie B. Prediction and prevention of thromboembolic events with enoxaparin in cancer patients with elevated tissue factor-bearing microparticles: a randomized-controlled phase II trial (the Microtec study) Br J Haematol. 2013;160:530–7. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwicker JI, Liebman HA, Neuberg D, Lacroix R, Bauer KA, Furie BC, Furie B. Tumor-derived tissue factor-bearing microparticles are associated with venous thromboembolic events in malignancy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6830–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Combes V, Simon AC, Grau GE, Arnoux D, Camoin L, Sabatier F, Mutin M, Sanmarco M, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with the lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:93–102. doi: 10.1172/JCI4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dignat-George F, Camoin-Jau L, Sabatier F, Arnoux D, Anfosso F, Bardin N, Veit V, Combes V, Gentile S, Moal V, Sanmarco M, Sampol J. Endothelial microparticles: a potential contribution to the thrombotic complications of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:667–73. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vikerfors A, Mobarrez F, Bremme K, Holmstrom M, Agren A, Eelde A, Bruzelius M, Antovic A, Wallen H, Svenungsson E. Studies of microparticles in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) Lupus. 2012;21:802–5. doi: 10.1177/0961203312437809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaturvedi S, Cockrell E, Espinola R, Hsi L, Fulton S, Khan M, Li L, Fonseca F, Kundu S, McCrae KR. Circulating microparticles in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies: characterization and associations. Thromb Res. 2015;135:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owens AP, III, Mackman N. Microparticles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Circ Res. 2011;108:1284–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton KK, Hattori R, Esmon CT, Simms PJ. Complement proteins C5b-9 induce vesiculation of the endothelial plasma membrane and expose catalytic surface for assembly of the prothrombinase enzyme complex. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3809–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Menzies KE, Wang JG, Hyrien O, Hathcock J, Mackman N, Taubman MB. Plasma tissue factor may be predictive of venous thromboembolism in pancreatic cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1983–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bang C, Thum T. Exosomes: new players in cell–cell communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:2060–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaiswal R, Luk F, Gong J, Mathys JM, Grau GE, Bebawy M. Microparticle conferred microRNA profiles – implications in the transfer and dominance of cancer traits. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:37. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaiswal R, Gong J, Sambasivam S, Combes V, Mathys JM, Davey R, Grau GE, Bebawy M. Microparticle-associated nucleic acids mediate trait dominance in cancer. FASEB J. 2012;26:420–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reich CF, III, Pisetsky DS. The content of DNA and RNA in microparticles released by Jurkat and HL-60 cells undergoing in vitro apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:760–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown GT, Narayanan P, Li W, Silverstein RL, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates platelets through an IL-1beta autocrine loop. J Immunol. 2013;191:5196–203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JG, Williams JC, Davis BK, Jacobson K, Doerschuk CM, Ting JP, Mackman N. Monocytic microparticles activate endothelial cells in an IL-1beta-dependent manner. Blood. 2011;118:2366–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boilard E, Nigrovic PA, Larabee K, Watts GF, Coblyn JS, Weinblatt ME, Massarotti EM, Remold-O’Donnell E, Farndale RW, Ware J, Lee DM. Platelets amplify inflammation in arthritis via collagen-dependent microparticle production. Science. 2010;327:580–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1181928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piccin A, Murphy WG, Smith OP. Circulating microparticles: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Blood Rev. 2007;21:157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lacroix R, Judicone C, Mooberry M, Boucekine M, Key NS, Dignat-George F. Standardization of pre-analytical variables in plasma microparticle determination: results of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis SSC Collaborative workshop. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;13:1190–93. doi: 10.1111/jth.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simantov R, LaSala JM, Lo SK, Gharavi AE, Sammaritano LR, Salmon JE, Silverstein RL. Activation of cultured vascular endothelial cells by antiphospholipid antibodies. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2211–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI118276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, McCrae KR. Annexin II mediates endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid/anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies. Blood. 2005;105:1964–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10:839–50. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma K, Simantov R, Zhang J-C, Silverstein R, Hajjar KA, McCrae KR. High affinity binding of b2-glycoprotein I to human endothelial cells is mediated by annexin II. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15541–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manly DA, Wang J, Glover SL, Kasthuri R, Liebman HA, Key NS, Mackman N. Increased microparticle tissue factor activity in cancer patients with venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2010;125:511–12. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothmeier AS, Marchese P, Petrich BG, Furlan-Freguia C, Ginsberg MH, Ruggeri ZM, Ruf W. Caspase-1-mediated pathway promotes generation of thromboinflammatory microparticles. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1471–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI79329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prinz N, Clemens N, Strand D, Putz I, Lorenz M, Daiber A, Stein P, Degreif A, Radsak M, Schild H, Bauer S, von Landenberg P, Lackner KJ. Antiphospholipid antibodies induce translocation of TLR7 and TLR8 to the endosome in human monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2011;118:2322–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ripoll VM, Lambrianides A, Pierangeli SS, Poulton K, Ioannou Y, Heywood WE, Mills K, Latchman DS, Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Giles IP. Changes in regulation of human monocyte proteins in response to IgG from patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood. 2014;124:3808–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satta N, Kruithof EK, Fickentscher C, Dunoyer-Geindre S, Boehlen F, Reber G, Burger D, de Moerloose P. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates the activation of human monocytes and endothelial cells by antiphospholipid antibodies. Blood. 2011;117:5523–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hornung V, Barchet W, Schlee M, Hartmann G. RNA recognition via TLR7 and TLR8. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;183:71–86. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewald SE, Barton GM. Nucleic acid sensing Toll-like receptors in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winkler CW, Taylor KG, Peterson KE. Location is everything: let-7b microRNA and TLR7 signaling results in a painful TRP. Sci Signal. 2014;7:e14. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarvestani ST, Stunden HJ, Behlke MA, Forster SC, McCoy CE, Tate MD, Ferrand J, Lennox KA, Latz E, Williams BR, Gantier MP. Sequence-dependent off-target inhibition of TLR7/8 sensing by synthetic microRNA inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1177–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE. MicroRNAs: the fine-tuners of Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:163–75. doi: 10.1038/nri2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chyung JH, Selkoe DJ. Inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis demonstrates generation of amyloid beta-protein at the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51035–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willemze R, Bradford RL, Mooberry MJ, Roubey RA, Key NS. Plasma microparticle tissue factor activity in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies with and without clinical complications. Thromb Res. 2014;133:187–9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, Tait JF, Tewari M. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. (A) Binding of affinity-purified anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies and fall through from the β2GPI affinity columns to β2GPI by ELISA (EL, column eluate; FT, flow-through). (B) Binding of affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies and fall through from the β2GPI affinity columns to cardiolipin in a standard anticardiolipin antibody assay in which plates were blocked with bovine serum. (C) Activation of endothelial cells (assessed by measurement of cell surface E-selectin expression) by control human IgG and the anti-β2GPI IgG from patient APS1 in the absence or presence of β2GPI. (D) Activation of endothelial cells by the non-β2GPI-reactive fall through IgG from patient APS1.

Fig. S2. Negligible amounts of β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) and anti-β2GPI IgG are adsorbed to extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs were isolated from endothelial cells treated with medium, β2GPI and control human IgG, β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Lysates prepared from quantities of EVs identical to those used for assessment of endothelial cell activation were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Known amounts of purified human IgG or β2GPI were used as standards (left lanes). In routine cell activation assays with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI IgG, we use ~ 1.6 μg of β2GPI and ~ 9 μg of anti-β2GPI IgG.

Fig. S3. Effect of Ac-YVAD-CMK on interleukin (IL)-1β and tissue factor (TF) expression in extracellular vesicles (EVs) from endothelial cells treated with anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies. Endothelial cells (ECs) were pretreated with Ac-YVAD-CMK (5 and 10 μM in Fig. 1A, and 5 μM in Fig. 1B) for 1 h before incubation with medium, β2GPI, and control human IgG, or β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG. EVs were isolated and analyzed for IL-1β expression by immunoblotting or labeled with FITC–conjugated control mouse IgG or FITC-conjugated antibodies against TF before analysis on an Apogee flow cytometer.

Fig. S4. (A) Reduction in target proteins following treatment of endothelial cells with siRNA against THR2, TLR7, or TLR9. (B) Reductions in endothelial cell TLR4 by different concentrations of TLR4 siRNA.

Fig. S5. RNase A digestion of extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs were isolated from endothelial cells treated with medium, β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), and control human IgG, β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). EVs were then digested with RNase A (100 μg mL−1) at 37 °C for 30 min, and this was followed by two washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). RNA was extracted from EVs with a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and run on a PicoChip. The figure demonstrates digestion of the majority of the small RNA while larger bands (arrows) remain relatively intact, suggesting that the RNase A did not freely permeate the EVs.

Fig. S6. Analysis of Toll-like receptor (TLR)7 expression on endothelial cells treated with anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI antibodies. (A) Endothelial cell surface-accessible proteins were labeled with sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin at 4 °C for 10 min. After preparation of the cell lysate, biotinylated proteins were pulled down with streptavidin beads. The pulled-down proteins were analyzed by western blotting for CD31 and β-actin expression. (B) Endothelial cells were treated with medium, β2GPI and control human IgG, or β2GPI and human anti-β2GPI IgG. Cell surface proteins were labeled and pulled down as in (A). The pulled-down proteins were then analyzed by immunoblotting for TLR7, CD31, and β-actin expression.

Fig. S7. Immunoblot of extracellular vesicle (EV) extracts for interleukin-1 receptor type I (IL-1RI).

Fig. S8. Activation of endothelial cells by extracellular vesicles (EVs) from a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is inhibited by dynasore. EVs from serum of one healthy control subject, or one APS patient was isolated by serial centrifugation, and then added to endothelial cells in a 96-well plate. Before addition of the EVs, endothelial cells were pretreated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or dynasore (50 μM). Each well was then incubated for 8 h with either medium alone or EVs from 100 μL of serum. Treated endothelial cells were assayed for cell surface E-selectin expression as described in Materials and methods. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Table S1. Primers used in interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) analyses.