Abstract

Glutamate signaling is achieved by an elaborate network involving neurons and astrocytes. Hence, it is critical to better understand how neurons and astrocytes interact to coordinate the cellular regulation of glutamate signaling. In these studies, we used rat cortical cell cultures to examine whether neurons or releasable neuronal factors were capable of regulating system xc− (Sxc), a glutamate releasing mechanism that is expressed primarily by astrocytes and has been shown to regulate synaptic transmission. We found that astrocytes cultured with neurons or exposed to neuronal conditioned media displayed significantly higher levels of Sxc activity. Next, we demonstrated that the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) may be a neuronal factor capable of regulating astrocytes. In support, we found that PACAP expression was restricted to neurons, and that PACAP receptors were expressed in astrocytes. Interestingly, blockade of PACAP receptors in cultures comprised of astrocytes and neurons significantly decreased Sxc activity to the level observed in purified astrocytes, while application of PACAP to purified astrocytes increased Sxc activity to the level observed in cultures comprised of neurons and astrocytes. Collectively, these data reveal that neurons coordinate the actions of glutamate-related mechanisms expressed by astrocytes such as Sxc, a process that likely involves PACAP.

Keywords: astrocyte, glutamate, system xc−, PACAP, neuron-astrocyte interaction, cystine

Introduction

Glutamate is often described as the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, in part because it may be present in up to 80% of all synapses (Curtis and Johnston, 1974; Choi, 1988; Harris and Kater, 1994; Meldrum, 2000; Franks et al., 2002; Javitt et al., 2011). As such, altered excitatory neurotransmission likely contributes to most CNS diseases (Carlsson and Carlsson, 1990; Olney, 1990; Brown and Bal-Price, 2003; Hynd et al., 2004; Maragakis and Rothstein, 2004; Foster and Kemp, 2006; Niswender and Conn, 2010; Rondard and Pin, 2015). While traditional models of glutamate signaling depict release solely from presynaptic terminals and diffusion throughout the synaptic cleft to activate pre- and postsynaptic receptors, it is becoming increasingly evident that excitatory neurotransmission is achieved by an elaborate network expressed across multiple types of cells that regulate signaling within and outside of the synaptic cleft (Herrera-Marschitz et al., 1996; Timmerman and Westerink, 1997; Jabaudon et al., 1999; Danbolt, 2001; Schoepp, 2001; Baker et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2003; Pirttimaki et al., 2011; Bridges et al., 2012). In support, astrocytes and neurons express glutamate receptors, transporters, and release mechanisms, and astrocyte to neuron signaling has been shown to be a key determinant of synaptic transmission (Porter and McCarthy, 1996; Pasti et al., 1997; Araque et al., 1999; Fellin et al., 2004; Perea and Araque, 2005; Fellin et al., 2006; Haydon and Carmignoto, 2006; Panatier et al., 2011; Santello et al., 2012; Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014; Gomez-Gonzalo et al., 2015). Therefore, decoding the complex molecular and cellular regulation of glutamate could lead to novel opportunities to better understand and treat pathological excitatory signaling.

A critical gap in modeling excitatory signaling is how distinct components of the glutamate system expressed by neurons and astrocytes are coordinated. In these experiments, we tested the hypothesis that neurons regulate the activity of glutamate-related mechanisms expressed by astrocytes. To do this, we examined the neuronal regulation of system xc− (Sxc), a non-canonical glutamate-release mechanism primarily expressed by astrocytes (Bannai and Kitamura, 1980, 1981; Sato et al., 1999; Pow, 2001; Zhang et al., 2014).

Sxc is a key component of glutamate signaling that is implicated in the pathology or treatment of multiple CNS diseases. It contributes to glutamate signaling by coupling the release of non-vesicular glutamate to the intracellular transport of cystine (Bannai and Kitamura, 1980, 1981; Sato et al., 1999). Manipulations that increase Sxc activity have been shown to a) influence multiple aspects of synaptic transmission and plasticity (Baker et al., 2002; Xi et al., 2002; Moran et al., 2005; Moussawi et al., 2009; Moussawi et al., 2011; Kupchik et al., 2012), b) normalize behavior in preclinical disease models (Baker et al., 2003; Madayag et al., 2007; Baker et al., 2008; Knackstedt et al., 2010; Alajaji et al., 2013; Lutgen et al., 2013), and c) exert therapeutic effects against multiple CNS diseases including drug addiction and schizophrenia (Berk et al., 2008; Amen et al., 2011; Lewerenz et al., 2013; Canavan et al., 2014; Verrico et al., 2014). Unfortunately, the regulation of Sxc is poorly understood.

In these studies, our primary objective was to evaluate the possibility that neurons regulate astrocyte Sxc activity. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) is a neuronal factor capable of regulating astrocyte Sxc activity. To do this, we verified that PACAP is expressed by rat cortical neurons and not astrocytes, and that rat cortical astrocytes express PACAP receptors. We then found that application of PACAP to cortical astrocytes increased Sxc activity. Moreover, inhibition of PACAP signaling blocked neuron-induced upregulation of Sxc. Collectively, these data are consistent with the possibility that altered neuronal activity could give rise to pathological changes in astrocyte functions, including altered Sxc activity which may be present in numerous CNS disorders ranging from drug addiction to schizophrenia.

Material and Methods

Animals and Materials

These experiments utilized cortical tissues obtained from Sprague Dawley rats (age was gestational day 15-16 or post-natal day 3-4; sex was undetermined; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN). Experimental procedures were approved by the Marquette University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The primary materials included fetal bovine serum and horse serum (Atlanta Biologicals; Lawrenceville, GA), 14C-cystine (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), PACAP1-38 (California Peptide Research, Napa, CA), and PACAP6-38 (Anaspec, Fremont, CA). PACAP1-38 (PACAP) is the endogenous full-length peptide whereas PACAP6-38 (P6-38) is a truncated version of PACAP and inhibits PACAP receptors (Miyata et al., 1989; Robberecht et al., 1992; Arimura, 2007; Vaudry et al., 2009).

Cell Culture Procedures

Purified cortical astrocyte cultures were prepared from post-natal days 3-4 rat pups. In brief, cortical cells were disassociated and then suspended in Neurobasal A media (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% Glutamax (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Cells were initially grown in 25cm2 or 75cm2 cell culture flasks. Once confluent, cells were then subjected to prolonged, orbital shaking (250 rpm for 18 hours at 37°C) which has been used to yield purified astrocyte cultures (McCarthy and de Vellis, 1980). Purified astrocytes were then plated on 24-well plates, and refreshed with 70% new culture media every 2-3 days.

Purified cortical neuronal cultures were prepared from embryonic rat cortical tissue (gestational day 15 to 16) as previously described (Lobner, 2000). In brief, dissociated cells were suspended in Eagles’ Minimal Essential Medium (MEM, Earle’s salts, glutamine-free) supplemented with glutamine (2mM), glucose (21mM), horse serum (5%), and fetal bovine serum (5%). Cells were seeded on 24-well plates. Forty eight hours later, cytosine arabinoside (at a final concentration of 10 μM) was added to the culture media to inhibit glial reproduction (Dugan et al., 1995). Neurons were then grown for an additional 11-13 days.

Mixed Neuronal and Glial Cultures

Procedure for preparing mixed cultures was identical to that of obtaining neuronal cultures (see above) except that cytosine arabinoside was not added to the culture media.

Physically Separated Astrocyte and Neuronal Cultures

Because the above mixed cultures also contained a limited number of non-astrocyte glial cells, and to determine whether neuron-astrocyte communication involves the release of a neuronal factor, we utilized a “non-contact” co-culture system in which purified astrocytes were physically separated from purified neurons. Note, these cells are referenced in the manuscript as Astrocytes + NCM (neuronal conditioned media). In these experiments, purified astrocytes were obtained as described above. When astrocytes reached confluency after 13-16 days in vitro (DIV), neuronal cultures were seeded on removable inserts (Corning, Corning, NY) that had been placed into the wells containing astrocytes, such that both cell types were immersed in the media but were not in physical contact. Fourteen days later, downstream experiments to examine the effects of neurons on astrocytes were performed upon removal of the neuronal inserts. As a result, the DIV for these cells was 27-30.

All cell-growing surfaces in culture flasks and 24-well plates were pre-coated with poly-D-lysine (10mg/L) and laminin (0.4mg/L). All cell cultures were maintained in humidified 5% CO2 incubators at 37°C.

14C-cystine Uptake Assay

The assessment of system xc− (Sxc) activity is often achieved by measuring intracellular uptake of radiolabeled cystine since this is primarily dependent on Sxc (Liu et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014; Resch et al., 2014; Albano et al., 2015). Note, we demonstrated that over 85% of 14C-cystine uptake in our cells was blocked by the Sxc inhibitor sulfasalazine (SSZ; see figure 3B). In contrast, extracellular glutamate is an insensitive indicator of Sxc since this is a product of numerous mechanisms (Swanson et al., 1997; Duan et al., 1999; Perego et al., 2000; Montana et al., 2004; Hires et al., 2008). Radiolabeled cystine uptake assays were performed as described previously with minor modifications (Liu et al., 2009). In brief, experiments were conducted in a bead bath at 37°C. Cells were washed 3 times with warm HEPES buffered saline solution, after which 14C-cystine was added to the media for 20 min at a final concentration of 0.3μM. This concentration was used since it is similar to extracellular cystine concentrations in the brain (Baker et al., 2003). DL-threo-β-Hydroxyaspartic acid (TBOA; 10 μM) was added to the culture media to prevent 14C-cystine uptake by sodium-dependent glutamate transporters. As described below, some of the experiments also involved the addition of the Sxc inhibitor SSZ (300 μM), PACAP, or P6-38. After incubating cells with 14C-cystine, cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold HEPES buffered saline solution, and then solubilized with 1M NaOH solution. One aliquot of cell lysate was used for protein determination using a BCA protein assay, and another aliquot was used for scintillation counting to measure the level of 14C-cystine uptake. 14C-cystine content was normalized to protein concentration. Data are presented as CPM/μg of protein.

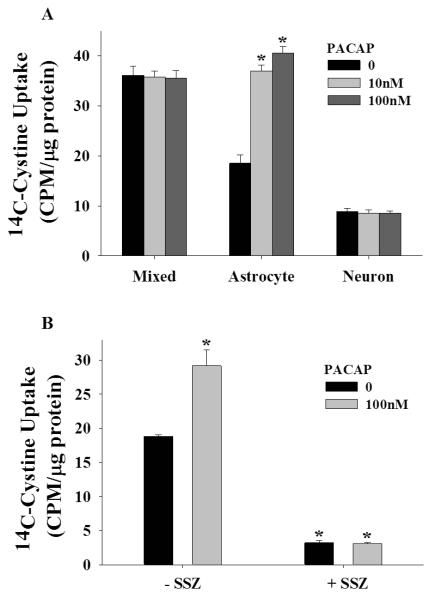

Figure 3.

PACAP upregulates Sxc activity in cortical astrocytes only. (A) Data depict mean ± SEM levels of 14C-cystine in rat cortical cell cultures after 24 hours PACAP treatment (0-100 nM; N=8/condition). * indicates a significant difference relative to vehicle-treated purified astrocyte cultures, Bonferroni, p <.001. (B) Data depict mean ± SEM levels of 14C-cystine in rat purified astrocyte cultures after 24 hours PACAP (0 or 100 nM) assessed in the presence of an Sxc inhibitor sulfasalazine (SSZ, 0 or 300 μM; N=4/condition). * indicates a significant difference relative to PACAP vehicle treated cells that were not exposed to SSZ (−SSZ), Bonferroni p <.001.

RNA extraction and cDNA construction

Total RNA was isolated from cell cultures with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacture’s protocol. DNase treatment was applied to all RNA samples to remove potential genomic DNA contamination with a DNA-free kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Assessment of RNA purity and quantity was performed on a NanoVue Plus Spectrophotometer (GE life sciences; Pittsburg, PA). cDNA was constructed from total RNA using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega; Madison, WI) with oligo(dT) primers following the manufacture’s protocol.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed using a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, CA) and PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix with ROX (Quanta Biosciences; Gaithersberg, MD). Relative quantification of target gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) using the ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). Primer sequences were as follows. xCT (catalytic subunit of Sxc) forward- 5′ AGG GCA TAC TCC AGA ACA CG 3′; xCT reverse- 5′ ATG CTC GTA CCC AAT TCA GC 3′; PACAP forward-5′ AAC CCG CTG CAA GAC TTC TA 3′; PACAP reverse- 5′ CTT TGC GGT AGG CTT CGT TA 3′; PAC1R forward- 5′ TGC CTG TGG CTA TTG CTA TG 3′; PAC1R reverse- 5′ TTT AGT CCC ATC AGG TCG TTG 3′; GAPDH forward- 5′ CTC CCA TTC TTC CAC CTT TGA 3′; GAPDH reverse- 5′ ATG TAG GCC ATG AGG TCC AC 3′. Primers were designed to be intron-spanning using the online primer design tool Primer3 (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi). A single product from amplification was confirmed by melt curve analysis. Amplification efficiency of all genes was determined to be approximately 95%.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 19, IBM; Armonk, New York). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when comparing data sets that included more than two groups. Bonferroni tests were used for subsequent post hoc analyses of significant effects involving more than two groups. Student’s t tests were used when comparing results from only two groups. In all instances, statistical significance was designated as p < 0.05.

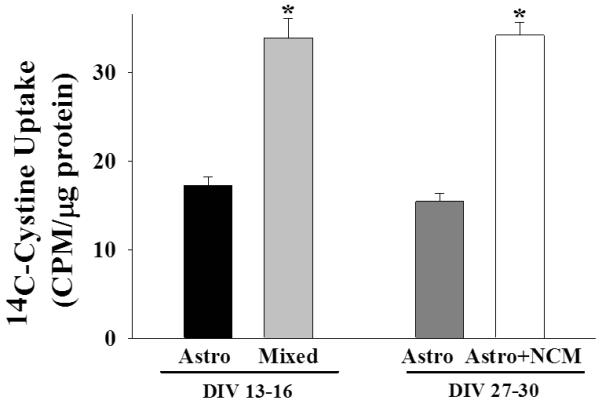

Experiment 1: Neuronal regulation of Sxc

The goal of this experiment was to test the hypothesis that a releasable neuronal factor regulates Sxc activity in astrocytes. To do this, we used two distinct approaches to co-express rat cortical neurons and astrocytes in culture. First, we measured 14C-cystine uptake in rat mixed cortical cultures (DIV 13-16). The advantage of this approach is that astrocytes are continuously grown in the presence of neurons. A disadvantage of this approach is that these cultures contain a limited number of microglia and oligodendrocytes. In addition, neurons physically contact astrocytes in these cultures. To address these two points, we also measured 14C-cystine uptake by astrocytes that had been exposed to neuron-conditioned media. To do this, we first generated purified astrocyte cultures as described above. When astrocytes reached confluency (typically 13-16 DIV), neuronal cultures were seeded on removable inserts which were placed into the wells containing astrocytes, such that both cell types were co-cultured yet with no physical contact. Fourteen days later, the neuronal inserts were removed, and 14C-cystine uptake was measured as described above. Note the 14-day period represents the time needed for the neurons to mature. The control cells in this experiment were purified astrocyte cultures in which the inserts lacked neurons. Tests using these cells occurred on DIV 27-30.

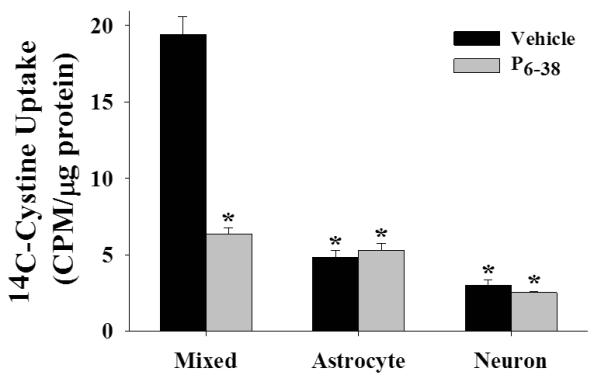

Experiment 2: Neuronal Upregulation of Sxc Requires PACAP Receptor Signaling

In an effort to begin to unmask the molecular basis of neuron-astrocyte signaling that regulates Sxc, we examined the impact of inhibiting PACAP receptors on cystine uptake in rat cortical cultures. Our interest in PACAP stems from previous studies showing that stimulation of PACAP receptors increases the activity of Sxc and GLT-1 (Figiel and Engele, 2000; Resch et al., 2014), both of which are primarily expressed by astrocytes (Rothstein et al., 1994; Lehre et al., 1995; Rothstein et al., 1996; Torp et al., 1997; Pow, 2001; Zhang et al., 2014). In this experiment, vehicle or 10 μM P6-38 (see Figiel and Engele, 2000 for concentration justification) was applied to rat cortical cultures (DIV 13-16) for 60 min, at which point 14C-cystine uptake was measured as described above.

Experiment 3: PACAP Upregulates Sxc on astrocytes

In this experiment, we tested the hypothesis that exogenous application of PACAP would significantly upregulate Sxc activity in purified astrocyte cultures. To test this, PACAP (0-100 nM) was applied to purified astrocyte cultures (DIV 13-16) for 24 hours. Afterwards, 14C-cystine uptake was measured as described above. This experiment was also conducted in purified neuronal and mixed cortical cultures although the predicted outcome was less certain given the likely expression of endogenous PACAP in these cultures.

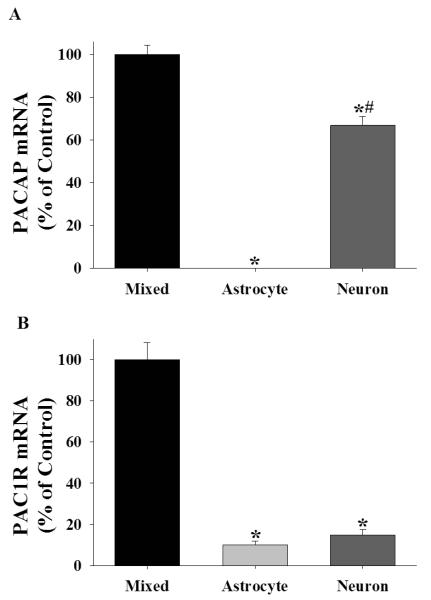

Experiment 4: Cellular Distribution of PACAP and PAC1R in rat cortical cultures

To further examine the possibility that PACAP is a neuronal factor capable of regulating astrocytes, we examined the cellular expression patterns of PACAP and its primary receptor, PAC1R. We were specifically interested in determining whether PACAP was solely expressed in neurons and PAC1R in purified astrocytes. To do this, we used RT-qPCR to measure mRNA expression for PACAP and PAC1R in mixed cultures, purified astrocyte cultures, and purified neuronal cultures (DIV 13-16).

Experiment 5: Regulation of xCT mRNA by Neurons and the Neuronal Factor PACAP

To better understand the observed upregulation of astrocyte Sxc by neurons or PACAP, we measured xCT mRNA in purified astrocytes and mixed cultures, purified astrocytes ± neuronal-conditioned media, and purified astrocytes ± PACAP.

Results

Experiment 1: Neuronal regulation of Sxc

To determine whether neurons are capable of regulating astrocyte Sxc activity, we used two approaches to permit neuron-astrocyte signaling. First, astrocyte and neurons were co-cultured upon plating (mixed cultures). This approach is designated in figure 1 as DIV 13-16, which refers to the number of days the cells had been cultured. In addition, confluent, purified astrocyte cultures were exposed to neuronal conditioned media (NCM) by placing neurons grown onto an insert into the wells containing the astrocytes for 14 days (as described in the methods for experiment 1). This approach is designated in figure 1 as DIV 27-30. A univariate ANOVA with DIV and culture cellular composition (i.e., astrocytes only or mixed or astrocyte + NCM) as between subjects factors produced a main effect of cell composition [figure 1; F(1,36)=77.979, p <.001] but not a main effect of DIV or an interaction between these variables. These findings illustrate that a releasable neuronal factor significantly upregulates Sxc activity on astrocytes (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Neurons upregulate Sxc activity in astrocytes. Data depict the mean ± SEM levels of 14C-cystine measured in rat cortical cells (N=8-12/condition) that had been cultured for 13-16 or 27-30 days in vitro (DIV). Astro, astrocytes; NCM, neuronal conditioned media. * represents a significant difference from corresponding purified astrocytes, p <.001.

Experiment 2: Neuronal upregulation of Sxc requires PACAP receptor signaling

Previous studies have shown that PACAP increases the activity of Sxc and GLT-1 (Figiel and Engele, 2000; Resch et al., 2014), both of which are primarily expressed by astrocytes (Rothstein et al., 1994; Lehre et al., 1995; Rothstein et al., 1996; Torp et al., 1997; Pow, 2001; Zhang et al., 2014). In an effort to reveal the molecular basis of neuron-astrocyte signaling that regulates Sxc, we examined the impact of inhibiting PACAP receptors with PACAP6-38 (P6-38) on 14C-cystine uptake in rat mixed, purified astrocyte, and purified neuronal cortical cultures. A univariate ANOVA with cell composition and P6-38 treatment (0 or 10 μM) as between-subjects variables yielded a significant interaction [figure 2; F(2,62)=73.849, p <.001]. To deconstruct the interaction, we compared 14C-cystine levels in vehicle-treated mixed cultures to every other condition. We found that vehicle-treated cultures containing neurons and astrocytes (i.e., mixed) displayed significantly higher levels of 14C-cystine, and that this effect was blocked by inhibiting PACAP receptors with PACAP6-38 (P6-38) (Bonferroni, p <.001). Interestingly, P6-38 did not alter 14C-cystine levels in purified astrocyte or in purified neuronal cultures. These data suggest that endogenous PACAP-induced upregulation of Sxc activity is only present in mixed cortical cultures (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of PACAP receptors blocks neuron-induced upregulation of Sxc. Data depict the uptake of 14C-cystine in rat cortical cultures in the presence or absence of the PACAP receptor inhibitor P6-38 (vehicle or 10 μM; N=6-12/condition). * indicates a significant difference relative to vehicle treated mixed cortical cultures, Bonferroni, p <.001.

Experiment 3: PACAP up-regulates Sxc on astrocytes

To confirm that PACAP promotes Sxc activity in rat cortical astrocytes, we compared 14C-cystine uptake in mixed cultures, purified astrocyte cultures, and purified neuronal cultures following PACAP application (24 hours) in the presence or absence of the Sxc inhibitor sulfasalazine (SSZ). A univariate ANOVA with culture cell composition and PACAP treatment as between subjects factors produced a significant interaction [figure 3A; F(4,62)=31.958, p <.001]. To further analyze the data, we examined the impact of PACAP on 14C-cystine uptake in each type of culture. A significant simple main effect of PACAP treatment was obtained only in purified astrocyte cultures [F(2,21)=75.904, p <.001]. Subsequent post hoc analyses revealed that PACAP increased uptake at 10 and 100 nM (Bonferroni, p <.001).

Although Sxc is primarily associated with astrocytes, we verified that PACAP-induced increases in 14C-cystine uptake reflects Sxc activity. To do this, we assessed the impact of PACAP on 14C-cystine uptake by astrocytes in the presence and absence of the Sxc inhibitor SSZ. A univariate ANOVA with PACAP and SSZ treatments as between-subjects factors resulted in a significant interaction [figure 3B; F(1,12)=19.130, p <.01]. Post hoc analyses indicated that PACAP increased 14C-cystine uptake in astrocytes when tested in the absence (Bonferroni, p <.001), but not in the presence of SSZ.

Experiment 4: Cellular distribution of PACAP and PAC1R in rat cortical cultures

To further examine the possibility that PACAP is a neuronal factor capable of regulating astrocytes, we assessed the cellular expression patterns of PACAP and its primary receptor, PAC1R (Gottschall et al., 1990; Lam et al., 1990). A one-way ANOVA with culture cell composition as a between-subjects factor yielded a main effect on PACAP mRNA levels [figure 4A; F(2,17)=294.774, p <.001]. Post hoc analyses revealed that mixed and purified neuronal cultures expressed the highest levels of PACAP mRNA (Bonferroni, p <.001). In fact, PACAP mRNA was not detectable in purified astrocyte cultures (figure 4A). A one-way ANOVA comparing the cellular distribution of PAC1R mRNA yielded a main effect of cell type [figure 4B; F(2,17)=93.863, p <.001]. Post hoc analyses revealed expression of PAC1R in every cell type, but with the highest levels evident in mixed cortical cultures (Bonferroni, p <.001). Collectively, these results demonstrate that in rat cortical cultures, PACAP is solely expressed in neurons and its primary receptor, PAC1R, is expressed by astrocytes.

Figure 4.

The cellular expression patterns of PACAP and its primary receptor, PAC1R, support the possibility that PACAP is a neuropeptide capable of regulating astrocyte Sxc activity. (A) Data depict mean ± SEM levels of PACAP mRNA in rat cortical cells cultures (N= 5-8/cell type). * indicates a significant difference relative to mixed cultures, Bonferroni, p <.001. # indicates a significant difference relative to purified astrocyte cultures, Bonferroni, p <.001. (B) Data depict mean ± SEM levels of PAC1R mRNA in rat purified astrocyte and neuronal cultures relative to that in cortical mixed cell cultures (N= 5-8/cell type). * indicates a significant difference relative to mixed cultures, Bonferroni, p <.001.

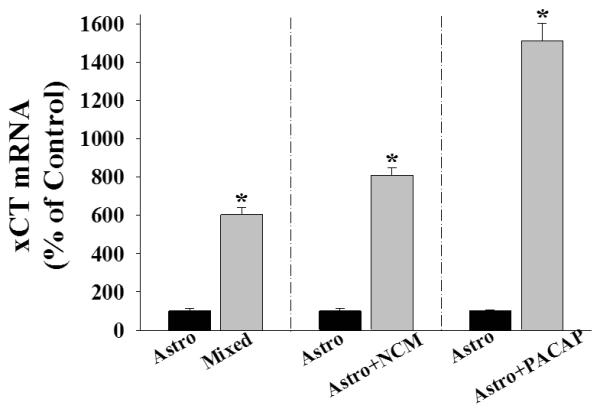

Experiment 5: Neurons and PACAP increase xCT mRNA

To better understand the observed upregulation of astrocyte Sxc activity by neurons or PACAP, we measured mRNA levels of xCT, the functional subunit of Sxc (Sato et al., 1999; Sato et al., 2000; Bridges et al., 2001). Mixed cultures of astrocytes and neurons [t(6)=17.734, p <.001], as well as purified astrocyte cultures exposed to NCM [t(13)=13.431, p <.001] expressed significantly higher levels of xCT mRNA relative to respective controls (figure 5). Similarly, PACAP application in purified astrocytes also robustly increased xCT mRNA [figure 5; t(10)=16.554, p <.001]. Together, these results suggest that the upregulation of astrocyte Sxc by neurons or PACAP may involve increased Sxc expression.

Figure 5.

Exposure to neurons and PACAP increase xCT mRNA in cultured cortical astrocytes. Data depict mean ± SEM levels of xCT mRNA (normalized to respective controls) in rat cortical cells cultures (N=4-12/condition). Astro refers to purified astrocyte cultures; mixed cells refer to cultures comprised of neurons and astrocytes; NCM refers to neuronal conditioned media achieved by placing neurons grown on inserts into the culture wells containing astrocytes for 14 days; PACAP treatment was for 24 hours at 10 nM. * indicates a significant difference relative to the respective control, t-test, p <.001.

Discussion

Glutamate signaling is achieved by an elaborate network likely requiring coordinated activity between neurons and astrocytes. In support, both cells express glutamate receptors, transporters, and release mechanisms (Choi, 1988; Greenamyre et al., 1988; Coyle and Puttfarcken, 1993; Moghaddam and Adams, 1998; Araque et al., 1999; Tapia et al., 1999; Marino et al., 2001; Franks et al., 2003; Haydon and Carmignoto, 2006; Javitt et al., 2011; Santello et al., 2012; Araque et al., 2014; Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014). The purpose of these experiments was to determine whether, and how, neurons regulate components of the glutamate system expressed by astrocytes. To do this, we focused on system xc− (Sxc) since this non-canonical release mechanism has been shown to be expressed primarily by astrocytes (Bannai and Kitamura, 1980, 1981; Sato et al., 1999; Pow, 2001; Zhang et al., 2014), significantly contributes to glutamate homeostasis (Baker et al., 2002; Xi et al., 2002; Melendez et al., 2005), regulates neuronal activity (Xi et al., 2002; Moran et al., 2005; Moussawi et al., 2009; Moussawi and Kalivas, 2010; Moussawi et al., 2011; Kupchik et al., 2012), and has been linked to multiple CNS diseases (Bridges et al., 2012; Lewerenz et al., 2013; Deepmala et al., 2015). Our major finding is that Sxc activity is significantly increased when astrocytes are exposed to neurons or to neuronal factors, including pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP). These findings are significant, in part, because they illustrate a novel form of neuron to astrocyte communication. Hence, pathological changes involving components of the glutamate system expressed by astrocytes, such as Sxc, may stem from aberrant activity of neuronal circuits.

Neuronal Regulation of Sxc

In these studies, we found that the uptake of 14C-cystine was higher in rat cortical cultures comprised of neurons and astrocytes relative to purified astrocyte cultures. One interpretation of these data is that neurons up-regulate Sxc activity in astrocytes. This conclusion, along with findings that neurons are critical in regulating the expression and activity of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters (Swanson et al., 1997; Figiel and Engele, 2000), highlights the need for neurons and astrocytes to display coordinated activity in order to achieve normal glutamate signaling. Alternative interpretations of our data include the possibility that neurons indirectly regulate Sxc activity. For example, neurons may influence the development of astrocytes, which may in turn influence Sxc.

In order to more directly test the hypothesis that a releasable neuronal factor coordinates Sxc activity on astrocytes, we evaluated the impact of neuronal conditioned media on 14C-cystine uptake in cortical astrocytes. In this experiment, purified astrocyte cultures were conditioned to neurons through a non-contact co-culture system, in which neurons seeded on removable inserts were placed in astrocyte cultures for 14 days. Afterwards, the neuronal inserts were removed in order to measure 14C-cystine uptake into astrocytes. Similar to our earlier finding, we found that cortical astrocytes that were exposed to neuronal conditioned media displayed significantly higher 14C-cystine uptake. We did not observe any other difference in the astrocyte cultures exposed to neuronal conditioned media from those lacking neurons. For example, the protein counts (mean ± SEM: astrocytes, 267.1 ± 6.8 μg/ml; astrocytes exposed to NCM, 254.4 ± 6.0 μg/ml) or cell confluency did not differ. As a result, these findings support the conclusion that neurons are capable of regulating components of the glutamate system expressed on astrocytes.

Regulation of Sxc by the neuropeptide PACAP

In an attempt to identify potential neuronal factors capable of regulating Sxc on astrocytes, we examined the possible involvement of PACAP since this peptide has been shown to be expressed by cortical neurons (Koves et al., 1991; Waschek et al., 1998; Figiel and Engele, 2000) and capable of regulating components of the glutamate system expressed by astrocytes including GLT-1 and GLAST in rat cortical glial cultures and Sxc in mouse glial cultures (Figiel and Engele, 2000; Resch et al., 2014). We sought to extend these studies by examining whether neuron-induced upregulation of 14C-cystine uptake requires PACAP signaling. Application of PACAP6-38 (P6-38), a truncated version of PACAP that inhibits PACAP receptors including PAC1R and VPAC2R, and also CART receptor (Robberecht et al., 1992; Gourlet et al., 1995; Laburthe et al., 2007; Hawke et al., 2009; Mounien et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2011), decreased 14C-cystine uptake in mixed cortical cultures to the level observed in purified astrocyte cultures. Interestingly, P6-38 did not alter 14C-cystine uptake in purified astrocytes or neurons. The results obtained in purified neuronal cultures likely reflect the relative lack of Sxc activity in these cells, although it should be noted that low amounts of 14C-cystine are detected in these cells. The lack of a P6-38 effect in purified astrocytes indicates the lack of endogenous PACAP signaling in these cells. Collectively, these data indicate that neuron-induced regulation of Sxc may involve PACAP signaling.

In order to further evaluate the conclusion that PACAP is a neuropeptide capable of directly regulating astrocytes, we examined the cellular distribution of mRNA for PACAP and its primary receptor, PAC1R. PACAP mRNA expression in cortical cultures was restricted to neurons, thereby establishing PACAP as a neuropeptide in these cultures. In contrast, both cortical neurons and astrocytes express mRNA for PAC1R, which has been shown to be the most abundant PACAP receptor that is expressed in cortical astrocytes (Zhang et al., 2014). However, PACAP also stimulates VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors, which are also expressed by astrocytes (Grimaldi and Cavallaro, 1999). Hence, there is a need to identify the receptor(s) that contributes to the regulation of Sxc by PACAP. Interestingly, we found significantly higher levels of PACAP and PAC1R in mixed cultures comprised of neurons and astrocytes, compared to either cell type cultured alone, which may suggest that astrocytes influence the neuronal PACAP system, although changes in mRNA do not always result in changes in protein expression and function. While future experiments are needed to further explore the potential for astrocyte-neuron communication to be an important determinant of PACAP signaling, our extant results are consistent with the possibility that PACAP is a neuropeptide capable of regulating components of the glutamate system expressed by astrocytes.

Next, we directly tested the hypothesis that PACAP application increases Sxc activity in astrocytes. We found that PACAP application significantly increased 14C-cystine uptake in rat cortical astrocytes, but not in mixed or purified neuronal cultures. While we anticipated PACAP-induced increases in 14C-cystine uptake in rat cortical astrocytes and a lack of an increase in purified neuronal cultures since these cells generally display little to no Sxc activity, we expected a modest increase in the mixed cortical cultures, an outcome we previously observed in mouse cultures (Resch et al., 2014). Aside from species, the difference between these studies is not clear, but likely reflects the existence of endogenous PACAP signaling. Collectively, these results are consistent with PACAP functioning as a neuronal factor controlling glutamate signaling involving astrocytes.

The nature of PACAP-induced regulation of Sxc in astrocytes is likely complex. For example, we found evidence that application of PACAP for 24 hours increased mRNA of xCT, the active subunit for Sxc. While increases in mRNA do not always result in augmented protein, it is important to note that PACAP also upregulated Sxc activity. Further, elevated xCT mRNA and increased Sxc activity were also evident in astrocytes cultured with neurons. Collectively, these data suggest that neurons influence the expression of Sxc in astrocytes. In addition, however, we found that relatively brief inhibition of PACAP signaling (i.e., 60 min) produced a significant reduction in Sxc activity, which suggests the possibility of post-translational modification. Additional studies are needed to better understand neuron or PACAP-induced regulation of Sxc.

Altered glutamate signaling likely underlies, at least in part, many disorders of the brain. Hence, it is critical to better understand how coordinated activity across distinct cell types involved in the transmission of this amino acid, is achieved. For example, Sxc has been implicated in several CNS diseases (Baker et al., 2003; Chung et al., 2005; Madayag et al., 2007; Baker et al., 2008; Knackstedt et al., 2010; Bridges et al., 2012; Lewerenz et al., 2013; Lutgen et al., 2013; Albano et al., 2015; Ching et al., 2015; Deepmala et al., 2015). Similarly, altered activity of GLT-1 and other glutamate transporters expressed by astrocytes has also been implicated in pathological glutamate transmission (Soni et al., 2014; Jensen et al., 2015; Roberts-Wolfe and Kalivas, 2015). In each case, however, it is unclear how glutamate signaling involving astrocytes may be altered. Collectively, these studies indicate that aberrant neural activity may be a novel factor underlying pathological changes in glutamate stemming from altered regulation of astrocytes. Moreover, PACAP itself is especially interesting in this regard as it has been shown to regulate glutamate uptake and release by astrocytes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under grant numbers DA017328 (DB) and DA015758 (JM).

Abbreviations

- Sxc

system xc−

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- P6-38

PACAP6-38

- Astro

astrocyte(s)

- DIV

day(s) in vitro

- SSZ

sulfasalazine

- TBOA

DL-threo-β-hydroxyaspartic acid

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alajaji M, Bowers MS, Knackstedt L, Damaj MI. Effects of the beta-lactam antibiotic ceftriaxone on nicotine withdrawal and nicotine-induced reinstatement of preference in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2013;228:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3047-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano R, Raddatz NJ, Hjelmhaug J, Baker DA, Lobner D. Regulation of System xc(−) by Pharmacological Manipulation of Cellular Thiols. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2015;2015:269371. doi: 10.1155/2015/269371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amen SL, Piacentine LB, Ahmad ME, Li SJ, Mantsch JR, Risinger RC, Baker DA. Repeated N-acetyl cysteine reduces cocaine seeking in rodents and craving in cocaine-dependent humans. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:871–878. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends in neurosciences. 1999;22:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG, Oliet SH, Robitaille R, Volterra A. Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron. 2014;81:728–739. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura A. PACAP: the road to discovery. Peptides. 2007;28:1617–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Xi ZX, Shen H, Swanson CJ, Kalivas PW. The origin and neuronal function of in vivo nonsynaptic glutamate. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22:9134–9141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Madayag A, Kristiansen LV, Meador-Woodruff JH, Haroutunian V, Raju I. Contribution of cystine-glutamate antiporters to the psychotomimetic effects of phencyclidine. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1760–1772. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Tang XC, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6:743–749. doi: 10.1038/nn1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S, Kitamura E. Transport interaction of L-cystine and L-glutamate in human diploid fibroblasts in culture. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1980;255:2372–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S, Kitamura E. Role of proton dissociation in the transport of cystine and glutamate in human diploid fibroblasts in culture. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1981;256:5770–5772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Copolov D, Dean O, Lu K, Jeavons S, Schapkaitz I, Anderson-Hunt M, Judd F, Katz F, Katz P, Ording-Jespersen S, Little J, Conus P, Cuenod M, Do KQ, Bush AI. N-acetyl cysteine as a glutathione precursor for schizophrenia--a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Biological psychiatry. 2008;64:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Kekuda R, Wang H, Prasad PD, Mehta P, Huang W, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Structure, function, and regulation of human cystine/glutamate transporter in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2001;42:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges R, Lutgen V, Lobner D, Baker DA. Thinking outside the cleft to understand synaptic activity: contribution of the cystine-glutamate antiporter (System xc−) to normal and pathological glutamatergic signaling. Pharmacological reviews. 2012;64:780–802. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC, Bal-Price A. Inflammatory neurodegeneration mediated by nitric oxide, glutamate, and mitochondria. Molecular neurobiology. 2003;27:325–355. doi: 10.1385/MN:27:3:325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavan SV, Forselius EL, Bessette AJ, Morgan PT. Preliminary evidence for normalization of risk taking by modafinil in chronic cocaine users. Addictive behaviors. 2014;39:1057–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M, Carlsson A. Interactions between glutamatergic and monoaminergic systems within the basal ganglia--implications for schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. Trends in neurosciences. 1990;13:272–276. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90108-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching J, Amiridis S, Stylli SS, Bjorksten AR, Kountouri N, Zheng T, Paradiso L, Luwor RB, Morokoff AP, O'Brien TJ, Kaye AH. The peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma agonist pioglitazone increases functional expression of the glutamate transporter excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2) in human glioblastoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous system. Neuron. 1988;1:623–634. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WJ, Lyons SA, Nelson GM, Hamza H, Gladson CL, Gillespie GY, Sontheimer H. Inhibition of cystine uptake disrupts the growth of primary brain tumors. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:7101–7110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5258-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DR, Johnston GA. Amino acid transmitters in the mammalian central nervous system. Ergebnisse der Physiologie, biologischen Chemie und experimentellen Pharmakologie. 1974;69:97–188. doi: 10.1007/3-540-06498-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Progress in neurobiology. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepmala, Slattery J, Kumar N, Delhey L, Berk M, Dean O, Spielholz C, Frye R. Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: A systematic review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2015;55:294–321. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan S, Anderson CM, Stein BA, Swanson RA. Glutamate induces rapid upregulation of astrocyte glutamate transport and cell-surface expression of GLAST. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:10193–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10193.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Bruno VM, Amagasu SM, Giffard RG. Glia modulate the response of murine cortical neurons to excitotoxicity: glia exacerbate AMPA neurotoxicity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1995;15:4545–4555. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04545.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Pascual O, Haydon PG. Astrocytes coordinate synaptic networks: balanced excitation and inhibition. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:208–215. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00161.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Pascual O, Gobbo S, Pozzan T, Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004;43:729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figiel M, Engele J. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), a neuron-derived peptide regulating glial glutamate transport and metabolism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20:3596–3605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03596.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster AC, Kemp JA. Glutamate- and GABA-based CNS therapeutics. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2006;6:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks KM, Bartol TM, Jr., Sejnowski TJ. A Monte Carlo model reveals independent signaling at central glutamatergic synapses. Biophysical journal. 2002;83:2333–2348. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75248-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks KM, Stevens CF, Sejnowski TJ. Independent sources of quantal variability at single glutamatergic synapses. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:3186–3195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03186.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gonzalo M, Navarrete M, Perea G, Covelo A, Martin-Fernandez M, Shigemoto R, Lujan R, Araque A. Endocannabinoids Induce Lateral Long-Term Potentiation of Transmitter Release by Stimulation of Gliotransmission. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:3699–3712. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschall PE, Tatsuno I, Miyata A, Arimura A. Characterization and distribution of binding sites for the hypothalamic peptide, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. Endocrinology. 1990;127:272–277. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlet P, Vandermeers A, Vandermeers-Piret MC, Rathe J, De Neef P, Robberecht P. Fragments of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide discriminate between type I and II recombinant receptors. European journal of pharmacology. 1995;287:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenamyre JT, Maragos WF, Albin RL, Penney JB, Young AB. Glutamate transmission and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 1988;12:421–430. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(88)90102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi M, Cavallaro S. Functional and molecular diversity of PACAP/VIP receptors in cortical neurons and type I astrocytes. The European journal of neuroscience. 1999;11:2767–2772. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Kater SB. Dendritic spines: cellular specializations imparting both stability and flexibility to synaptic function. Annual review of neuroscience. 1994;17:341–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawke Z, Ivanov TR, Bechtold DA, Dhillon H, Lowell BB, Luckman SM. PACAP neurons in the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus are targets of central leptin signaling. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:14828–14835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1526-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiological reviews. 2006;86:1009–1031. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Marschitz M, You ZB, Goiny M, Meana JJ, Silveira R, Godukhin OV, Chen Y, Espinoza S, Pettersson E, Loidl CF, Lubec G, Andersson K, Nylander I, Terenius L, Ungerstedt U. On the origin of extracellular glutamate levels monitored in the basal ganglia of the rat by in vivo microdialysis. Journal of neurochemistry. 1996;66:1726–1735. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hires SA, Zhu Y, Tsien RY. Optical measurement of synaptic glutamate spillover and reuptake by linker optimized glutamate-sensitive fluorescent reporters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:4411–4416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712008105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynd MR, Scott HL, Dodd PR. Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochemistry international. 2004;45:583–595. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabaudon D, Shimamoto K, Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. Inhibition of uptake unmasks rapid extracellular turnover of glutamate of nonvesicular origin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:8733–8738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Schoepp D, Kalivas PW, Volkow ND, Zarate C, Merchant K, Bear MF, Umbricht D, Hajos M, Potter WZ, Lee CM. Translating glutamate: from pathophysiology to treatment. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:102mr102. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AA, Fahlke C, Bjorn-Yoshimoto WE, Bunch L. Excitatory amino acid transporters: recent insights into molecular mechanisms, novel modes of modulation and new therapeutic possibilities. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2015;20:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW. Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koves K, Arimura A, Gorcs TG, Somogyvari-Vigh A. Comparative distribution of immunoreactive pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in rat forebrain. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;54:159–169. doi: 10.1159/000125864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupchik YM, Moussawi K, Tang XC, Wang X, Kalivas BC, Kolokithas R, Ogburn KB, Kalivas PW. The effect of N-acetylcysteine in the nucleus accumbens on neurotransmission and relapse to cocaine. Biological psychiatry. 2012;71:978–986. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laburthe M, Couvineau A, Tan V. Class II G protein-coupled receptors for VIP and PACAP: structure, models of activation and pharmacology. Peptides. 2007;28:1631–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HC, Takahashi K, Ghatei MA, Kanse SM, Polak JM, Bloom SR. Binding sites of a novel neuropeptide pituitary-adenylate-cyclase-activating polypeptide in the rat brain and lung. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1990;193:725–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehre KP, Levy LM, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Danbolt NC. Differential expression of two glial glutamate transporters in the rat brain: quantitative and immunocytochemical observations. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1995;15:1835–1853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01835.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M, Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M, Smith SB, Ganapathy V, Maher P. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(−) in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2013;18:522–555. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Hall RA, Kuhar MJ. CART peptide stimulation of G protein-mediated signaling in differentiated PC12 cells: identification of PACAP 6-38 as a CART receptor antagonist. Neuropeptides. 2011;45:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Albano R, Lobner D. FGF-2 induces neuronal death through upregulation of system xc. Brain research. 2014;1547:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Rush T, Zapata J, Lobner D. beta-N-methylamino-l-alanine induces oxidative stress and glutamate release through action on system Xc(−) Experimental neurology. 2009;217:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobner D. Comparison of the LDH and MTT assays for quantifying cell death: validity for neuronal apoptosis? Journal of neuroscience methods. 2000;96:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgen V, Qualmann K, Resch J, Kong L, Choi S, Baker DA. Reduction in phencyclidine induced sensorimotor gating deficits in the rat following increased system xc(−) activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology. 2013;226:531–540. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2926-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madayag A, Lobner D, Kau KS, Mantsch JR, Abdulhameed O, Hearing M, Grier MD, Baker DA. Repeated N-acetylcysteine administration alters plasticity-dependent effects of cocaine. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:13968–13976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2808-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maragakis NJ, Rothstein JD. Glutamate transporters: animal models to neurologic disease. Neurobiology of disease. 2004;15:461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino MJ, Wittmann M, Bradley SR, Hubert GW, Smith Y, Conn PJ. Activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors produces a direct excitation and disinhibition of GABAergic projection neurons in the substantia nigra pars reticulata. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:7001–7012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. The Journal of cell biology. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. The Journal of nutrition. 2000;130:1007S–1015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RI, Vuthiganon J, Kalivas PW. Regulation of extracellular glutamate in the prefrontal cortex: focus on the cystine glutamate exchanger and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2005;314:139–147. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata A, Arimura A, Dahl RR, Minamino N, Uehara A, Jiang L, Culler MD, Coy DH. Isolation of a novel 38 residue-hypothalamic polypeptide which stimulates adenylate cyclase in pituitary cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1989;164:567–574. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Adams BW. Reversal of phencyclidine effects by a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist in rats. Science. 1998;281:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana V, Ni Y, Sunjara V, Hua X, Parpura V. Vesicular glutamate transporter-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:2633–2642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3770-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MM, McFarland K, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW, Seamans JK. Cystine/glutamate exchange regulates metabotropic glutamate receptor presynaptic inhibition of excitatory transmission and vulnerability to cocaine seeking. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:6389–6393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1007-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounien L, Do Rego JC, Bizet P, Boutelet I, Gourcerol G, Fournier A, Brabet P, Costentin J, Vaudry H, Jegou S. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibits food intake in mice through activation of the hypothalamic melanocortin system. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:424–435. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussawi K, Kalivas PW. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlu2/3) in drug addiction. European journal of pharmacology. 2010;639:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussawi K, Pacchioni A, Moran M, Olive MF, Gass JT, Lavin A, Kalivas PW. N-Acetylcysteine reverses cocaine-induced metaplasticity. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussawi K, Zhou W, Shen H, Reichel CM, See RE, Carr DB, Kalivas PW. Reversing cocaine-induced synaptic potentiation provides enduring protection from relapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:385–390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011265108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW. Excitotoxic amino acids and neuropsychiatric disorders. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 1990;30:47–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A, Vallee J, Haber M, Murai KK, Lacaille JC, Robitaille R. Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell. 2011;146:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasti L, Volterra A, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Intracellular calcium oscillations in astrocytes: a highly plastic, bidirectional form of communication between neurons and astrocytes in situ. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07817.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G, Araque A. Properties of synaptically evoked astrocyte calcium signal reveal synaptic information processing by astrocytes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:2192–2203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3965-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego C, Vanoni C, Bossi M, Massari S, Basudev H, Longhi R, Pietrini G. The GLT-1 and GLAST glutamate transporters are expressed on morphologically distinct astrocytes and regulated by neuronal activity in primary hippocampal cocultures. Journal of neurochemistry. 2000;75:1076–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Alvarez A, Navarrete M, Covelo A, Martin ED, Araque A. Structural and functional plasticity of astrocyte processes and dendritic spine interactions. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:12738–12744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2401-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirttimaki TM, Hall SD, Parri HR. Sustained neuronal activity generated by glial plasticity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:7637–7647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5783-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:5073–5081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pow DV. Visualising the activity of the cystine-glutamate antiporter in glial cells using antibodies to aminoadipic acid, a selectively transported substrate. Glia. 2001;34:27–38. doi: 10.1002/glia.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch JM, Albano R, Liu X, Hjelmhaug J, Lobner D, Baker DA, Choi S. Augmented cystineglutamate exchange by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide signaling via the VPAC1 receptor. Synapse. 2014 doi: 10.1002/syn.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robberecht P, Gourlet P, De Neef P, Woussen-Colle MC, Vandermeers-Piret MC, Vandermeers A, Christophe J. Structural requirements for the occupancy of pituitary adenylate-cyclase-activating-peptide (PACAP) receptors and adenylate cyclase activation in human neuroblastoma NB-OK-1 cell membranes. Discovery of PACAP(6-38) as a potent antagonist. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1992;207:239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Wolfe DJ, Kalivas PW. Glutamate Transporter GLT-1 as a Therapeutic Target for Substance Use Disorders. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 2015;14:745–756. doi: 10.2174/1871527314666150529144655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondard P, Pin JP. Dynamics and modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2015;20:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin L, Levey AI, Dykes-Hoberg M, Jin L, Wu D, Nash N, Kuncl RW. Localization of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters. Neuron. 1994;13:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, Bristol LA, Jin L, Kuncl RW, Kanai Y, Hediger MA, Wang Y, Schielke JP, Welty DF. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santello M, Cali C, Bezzi P. Gliotransmission and the tripartite synapse. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2012;970:307–331. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, Bannai S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:11455–11458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Tamba M, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, Okuno S, Bannai S. Molecular cloning and expression of human xCT, the light chain of amino acid transport system xc. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2000;2:665–671. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.4-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nature protocols. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp DD. Unveiling the functions of presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in the central nervous system. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2001;299:12–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni N, Reddy BV, Kumar P. GLT-1 transporter: an effective pharmacological target for various neurological disorders. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2014;127:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson RA, Liu J, Miller JW, Rothstein JD, Farrell K, Stein BA, Longuemare MC. Neuronal regulation of glutamate transporter subtype expression in astrocytes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:932–940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00932.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia R, Medina-Ceja L, Pena F. On the relationship between extracellular glutamate, hyperexcitation and neurodegeneration, in vivo. Neurochemistry international. 1999;34:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(98)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman W, Westerink BH. Brain microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: what does it signify? Synapse. 1997;27:242–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199711)27:3<242::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torp R, Hoover F, Danbolt NC, Storm-Mathisen J, Ottersen OP. Differential distribution of the glutamate transporters GLT1 and rEAAC1 in rat cerebral cortex and thalamus: an in situ hybridization analysis. Anatomy and embryology. 1997;195:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s004290050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, Basille M, Burel D, Wurtz O, Fournier A, Chow BK, Hashimoto H, Galas L, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacological reviews. 2009;61:283–357. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrico CD, Haile CN, Mahoney JJ, 3rd, Thompson-Lake DG, Newton TF, De La Garza R., 2nd Treatment with modafinil and escitalopram, alone and in combination, on cocaine-induced effects: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled human laboratory study. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014;141:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschek JA, Casillas RA, Nguyen TB, DiCicco-Bloom EM, Carpenter EM, Rodriguez WI. Neural tube expression of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) and receptor: potential role in patterning and neurogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:9602–9607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Baker DA, Shen H, Carson DS, Kalivas PW. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2002;300:162–171. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O'Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, Guarnieri P, Caneda C, Ruderisch N, Deng S, Liddelow SA, Zhang C, Daneman R, Maniatis T, Barres BA, Wu JQ. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]