Abstract

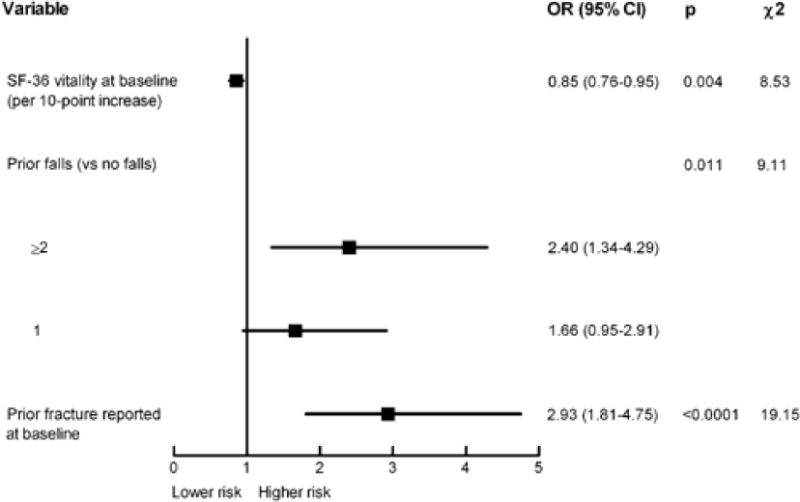

Anti-osteoporosis medication (AOM) does not abolish fracture risk, and some individuals experience multiple fractures while on treatment. Therefore, criteria for treatment failure have recently been defined. Using data from the Global Longitudinal study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW), we analyzed risk factors for treatment failure, defined as sustaining ≥2 fractures while on AOM. GLOW is a prospective, observational cohort study of women aged ≥55 years sampled from primary care practices in 10 countries. Self-administered questionnaires collected data on patient characteristics, fracture risk factors, previous fractures, AOM use, and health status. Data were analyzed from women who used the same class of AOM continuously over 3 survey-years and had data available on fracture occurrence. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of treatment failure. Data from 26,918 women were available, of whom 5550 were on AOM. During follow-up, 73/5550 women in the AOM group (1.3%) and 123/21,368 in the non-AOM group (0.6%) reported occurrence of ≥2 fractures. The following variables were associated with treatment failure: lower SF-36 score (physical function and vitality) at baseline, higher FRAX score, falls in the past 12 months, selected comorbid conditions, prior fracture, current use of glucocorticoids, need of arms to assist to standing, and unexplained weight loss ≥10 lb (≥4.5 kg). Three variables remained predictive of treatment failure after multivariable analysis: worse SF-36 vitality score (odds ratio [OR] per 10-point increase 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.76–0.95; p = 0.004), ≥2 falls in the past year (OR 2.40; 95% CI 1.34–4.29; p = 0.011), and prior fracture (OR 2.93; 95% CI 1.81–4.75; p < 0.0001). The C statistic for the model was 0.712. Specific strategies for fracture prevention should therefore be developed for this subgroup of patients.

Keywords: TREATMENT FAILURE, ANTIRESORPTIVE THERAPY, RISK FACTORS, OSTEOPOROSIS TREATMENT

Introduction

Several antiosteoporosis medications (AOMs) are efficacious in reducing risk of fracture in postmenopausal women.(1) Unfortunately, fractures still occur while on AOM, even among patients who are adherent to these regimens. Such occurrences are not unexpected, as even under optimal clinical trial conditions, medications only reduce fracture risk by up to 70% for vertebral fractures, 20% for non-vertebral fractures, and 40% for hip fractures, depending on the drug, with some of the antiresorptives only showing efficacy against vertebral fracture.(2–8) Concern has been raised, however, over a subgroup of women who experience multiple fractures while on AOM.(9) An expert group representing the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) has designated the problem of ≥2 episodes of fracture occurring while taking therapies used to reduce the risk of fracture as “treatment failure”.(10)

The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW) is a prospective cohort study of postmenopausal women, in which data on osteoporosis, fractures, and treatments for osteoporosis are collected, along with other health information. The aim of the present analysis is to capture the characteristics of women in the GLOW cohort that suffer ≥2 fractures while on continuous AOM treatment in order to identify independent predictors of treatment failure.

Materials and Methods

GLOW is a prospective cohort study involving 723 physician practices at 17 sites in 10 countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, UK, and USA). The study methods have been reported previously.(11) In brief, practices typical of each region were recruited through primary care networks organized for administrative, research, or educational purposes, or by identifying all physicians in a geographic area. Each site obtained local ethics committee approval to participate in the study. The practices provided the names of women aged ≥55 years who had been seen by their physician in the past 24 months. After the exclusion of women due to cognitive impairment, language barriers, institutionalization or who were too ill,(11) 60,393 women agreed to participate in the study.

Questionnaires were designed to be self administered and covered domains that included: patient characteristics and risk factors for fracture; fracture history; current medication use; and other medical diagnoses. Information was collected at baseline on history of previous fractures (that had occurred since the age of 45 years), while incident fractures were assessed during the 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up surveys. All surveys included details on fracture location and the occurrence of single or multiple fractures. Subjects were considered to be taking AOM if they reported current use of alendronate, calcitonin, estrogen, etidronate, ibandronate, pamidronate, recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–84), raloxifene, risedronate, strontium ranelate, teriparatide, tibolone, or zoledronic acid (denosumab was not available at the time of the data collection in GLOW). Information was also obtained about comorbid conditions including asthma, emphysema, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, colitis, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, cancer, and type 1 diabetes.

Among the women participating in GLOW, eligible cases in this analysis were those who remained on the same class of AOM for all 3 survey years and who had data available on incident fracture. All other women were excluded from the analysis. The “not on AOM” group were women that received no prescription drugs against osteoporosis during the whole study period.

Fractures included incident fracture at any of the following 15 sites: clavicle, arm, wrist, spine, rib, hip, pelvis, ankle, upper leg, lower leg, hand, foot, elbow, knee, or shoulder. One fracture while on AOM was defined as self-report of the occurrence of a single fracture while reporting AOM use on the two surveys prior to as well as during the year of the fracture. Women who reported a single fracture during their first year on AOM were not considered to have had a fracture while on treatment, based on the assumption that the drugs require time to reach their full efficacy.(9) Two or more fractures while on AOM was defined as self-report of multiple fracture episodes while reporting current AOM use on three consecutive surveys; the first fracture must have occurred after treatment began, and subsequent fractures must have occurred after 1 year of treatment. Women in the “not on AOM” group had not reported AOM use in the baseline survey and in each of the annual follow-up surveys (four study years). Women in the “no fracture” group did not sustain any fractures during all four study years.

According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) Working Group definition for treatment failure, a case was classified as treatment failure if ≥2 incident fractures were reported while on AOM.(10) Other criteria, such as bone remodeling markers and variations in bone density, were not considered as this information is not available in GLOW.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are shown as frequencies with percentages; tests for difference were computed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test in the case of small cell values. Continuous variables are shown as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles, with the Mann-Whitney U test used to test for differences. A multivariable model predicting failure on treatment (≥2 versus 0 fractures) was fit using backwards selection, beginning with all variables that were significant (p < 0.20) on the univariate level between those two groups. Variables that remained significant (p < 0.05) were retained in the final multivariable model. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

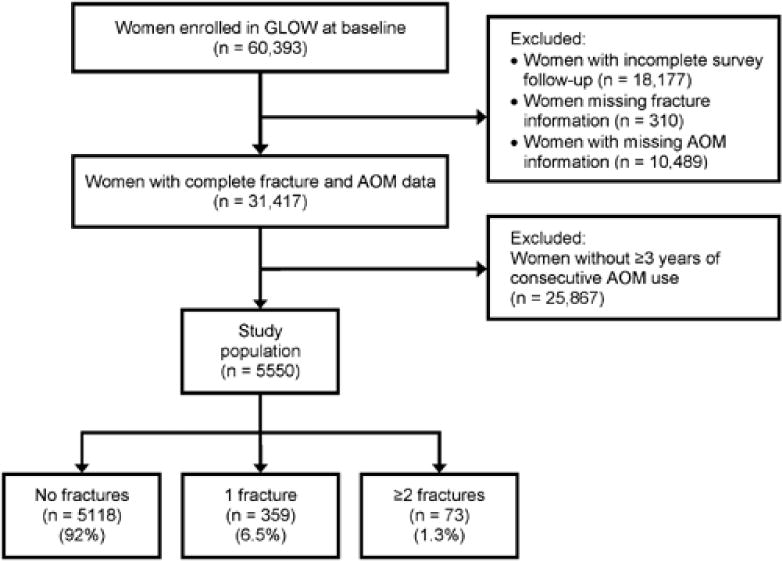

In this study, 5550 women reported 3 years of continuous use of a single class of AOM. Of these, 359 (6.5%) women experienced a single fracture and 73 (1.3%) women had ≥2 fractures (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of the women, according to the number of fractures, are given in Table 1. Women who had ≥2 fractures were similar in age to those with no fractures but slightly younger than those with a single fracture. Women with ≥2 incident fractures reported a higher rate of ≥2 falls at baseline and higher frequency of ≥2 comorbid conditions. The FRAX 10-year fracture risk for major fracture(12) was greater in women with ≥2 fractures compared to those with no fractures, as demonstrated by the higher rates of each of the seven FRAX risk factors. A similar pattern was noted for the Garvan 5-year risk of any osteoporotic fracture. Prior fracture and current cortisone use were higher among women with multiple fractures versus those with no fracture (Table 1).

Figure 1.

GLOW flowchart. GLOW = Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Fracture Group

| ≥2 fractures while on AOM (n = 73) |

1 fracture while on AOM (n = 359) |

No fractures while on AOM (n = 5118) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 (63, 77) | 72 (65, 78) | 69 (63, 76) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24 (22, 28) | 24 (22, 28) | 24 (22, 27) |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Asthma | 12 (17) | 44 (12) | 549 (11) |

| Cancer | 13 (19) | 62 (17) | 813 (16) |

| Celiac disease | 1 (1.4) | 3 (0.9) | 44 (0.9) |

| Chronic bronchitis or emphysemac | 11 (16) | 34 (9.7) | 372 (7.4) |

| Diabetesc | 4 (5.6) | 18 (5.1) | 90 (1.8) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2 (2.8) | 3 (0.9) | 36 (0.7) |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative joint diseasec | 43 (59) | 179 (52) | 2216 (44) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 0 | 4 (1.1) | 25 (0.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (2.8) | 6 (1.7) | 75 (1.5) |

| Stroke | 4 (5.7) | 16 (4.5) | 168 (3.3) |

| Ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease | 1 (1.4) | 7 (2.0) | 110 (2.2) |

| Number of comorbid conditionsc | |||

| 0 | 37 (51) | 206 (57) | 3339 (65) |

| 1 | 24 (33) | 116 (32) | 1359 (27) |

| ≥2 | 12 (16) | 37 (10) | 419 (8.2) |

| Falls in past 12 monthsc | |||

| 0 | 32 (44) | 180 (51) | 3260 (64) |

| 1 | 21 (29) | 97 (27) | 1157 (23) |

| ≥2 | 20 (27) | 78 (22) | 671 (13) |

| FRAX risk factors | |||

| Prior fracturec | 45 (62) | 162 (47) | 1620 (32) |

| Weight <125 lb (<57 kg) | 24 (33) | 99 (28) | 1391 (28) |

| Parental fracture | 17 (25) | 80 (25) | 1015 (22) |

| Current smoker | 6 (8.3) | 26 (7.3) | 333 (6.5) |

| Current cortisone usec | 7 (9.6) | 28 (7.9) | 225 (4.5) |

| Secondary osteoporosisa | 17 (24) | 75 (22) | 971 (20) |

| Alcohol (>20 drinks/week) | 1 (1.4) | 5 (1.4) | 12 (0.2) |

| Measure of health status | |||

| SF-36 – physical functionc | 65 (40, 90) | 80 (50, 90) | 85 (61, 95) |

| SF-36 – vitalityc | 56 (38, 69) | 63 (50, 75) | 63 (50, 75) |

| FRAX 10-year fracture risk, %c | 20 (11, 29) | 19 (12, 28) | 15 (9, 23) |

| Garvan 10-year fracture risk, % c | 32 (17, 59) | 28 (18, 49) | 21 (14, 34) |

| Garvan 5-year fracture risk, %c | 17 (9, 35) | 14 (9, 27) | 11 (7, 18) |

| Frailty measures | |||

| Arms to assist to standingc | 35 (48) | 127 (36) | 1582 (31) |

| Unexplained weight loss ≥10 lb (≥4.5 kg) c | 10 (14) | 30 (8.5) | 367 (7.3) |

| Fair or poor general healthc | 26 (36) | 79 (22) | 1003 (20) |

| Number of prior fracturesb | |||

| 0 | 28 (38) | 186 (53) | 3404 (68) |

| 1 | 25 (34) | 97 (28) | 1174 (23) |

| ≥2 | 20 (27) | 65 (19) | 446 (8.9) |

| Site of baseline fracture | |||

| Collar bone or clavicle | 1 (1.4) | 9 (2.5) | 82 (1.6) |

| Upper armc | 11 (15) | 27 (7.5) | 235 (4.6) |

| Wristc | 15 (21) | 68 (19) | 614 (12) |

| Spinec | 12 (16) | 26 (7.3) | 202 (4.0) |

| Ribc | 15 (21) | 39 (11) | 274 (5.4) |

| Hip | 3 (4.2) | 16 (4.5) | 135 (2.7) |

| Pelvis | 2 (2.7) | 17 (4.8) | 90 (1.8) |

| Ankle | 9 (12) | 30 (8.4) | 379 (7.5) |

| Upper legc | 4 (5.5) | 11 (3.1) | 57 (1.1) |

| Lower legc | 7 (9.6) | 21 (6.0) | 156 (3.1) |

Data are median (25th, 75th percentile) or number (%).

Use of anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole; diagnosis of celiac disease or colitis, type 1 diabetes, or menopause before age 45 years.

Occurring since the age of 45 years, and including fracture of clavicle, arm, wrist, spine, rib, hip, pelvis, ankle, upper leg, or lower leg (reported on baseline survey).

p<0.05 between groups with ≥2 fractures and those with no fractures.

When measures of health status were evaluated, women with ≥2 fractures had lower scores on the SF-36 measures of physical function and vitality,(13) more reports of unexplained weight loss ≥10 lb (4.5 kg), more frequently needed their arms to assist in rising from a chair, and more often rated their general health as fair or poor (Table 1).

Proportionately more incident fractures of the rib, ankle, foot, upper arm, upper leg, pelvis, and elbow were reported by women with multiple fractures compared to those with a single incident fracture (each p<0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Incident Fractures by Fracture Type

| ≥2 fractures while on AOM (n = 73) |

1 fracture while on AOM (n = 359) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rib | 21 (29) | 65 (18) | 0.040 |

| Wrist | 19 (26) | 77 (22) | 0.42 |

| Ankle | 17 (23) | 30 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Foot | 14 (19) | 38 (11) | 0.040 |

| Upper arm | 10 (14) | 21 (5.9) | 0.019 |

| Spine | 11 (15) | 48 (13) | 0.72 |

| Upper leg | 10 (14) | 13 (3.6) | 0.002a |

| Hip | 9 (12) | 23 (6.4) | 0.08 |

| Pelvis | 9 (12) | 18 (5.1) | 0.031a |

| Elbow | 7 (9.6) | 11 (3.1) | 0.020a |

| Lower leg | 6 (8.2) | 15 (4.2) | 0.15a |

| Collar bone or clavicle | 4 (5.5) | 11 (3.1) | 0.30a |

| Knee | 3 (4.1) | 19 (5.3) | 0.99a |

| Hand | 2 (2.7) | 8 (2.2) | 0.68a |

| Shoulder | 2 (2.7) | 19 (5.3) | 0.55a |

Data are number (%).

Fisher’s exact test.

More than 80% of the women in each of the three groups (≥2, 1, or 0 incident fractures) were taking a bisphosphonate (Table 3). The second most frequently used class of AOMs was selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (i.e. raloxifene), reported by 5.5% of women with ≥2 fractures and 12% with no fractures.

Table 3.

Class of Anti-Osteoporosis Medication Received

| ≥2 fractures while on AOM (n = 73) |

1 fracture while on AOM (n = 359) |

No fractures while on AOM (n = 5118) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphosphonate (oral) | 64 (88) | 312 (87) | 4213 (82) |

| Bisphosphonate (injection or infusion) | 3 (4.1) | 5 (1.4) | 56 (1.1) |

| Parathyroid hormone | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) |

| SERM | 4 (5.5) | 34 (9.5) | 602 (12) |

| Calcitonin hormone | 1 (1.4) | 3 (0.8) | 48 (0.9) |

| Strontium ranelate | 0 | 5 (1.4) | 80 (1.6) |

| Steroid hormone | 1 (1.4) | 2 (0.6) | 161 (3.2) |

| Bisphosphonates + SERM | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 41 (0.8) |

| Bisphosphonates + strontium ranelate | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Bisphosphonates + steroid hormone | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.02) |

| Bisphosphonates + calcitonin hormone | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.1) |

| Calcitonin hormone + strontium ranelate | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.02) |

SERM = selective estrogen receptor modulator.

Independent predictors of treatment failure

Multivariable modeling to predict the occurrence of multiple fractures identified three factors (available at baseline) associated with treatment failure: lower SF-36 vitality score, ≥2 falls in the previous year, and prior fracture (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Independent predictors of treatment failure. C statistic = 0.712.

Discussion

In this large, international, observational cohort study of postmenopausal women, reduced quality of life, as measured by the vitality subscale of the SF-36 health survey,(13) prior falls, and prior fracture were independently predictive of treatment failure while on AOM. Although several of the risk factors included in the FRAX algorithm(12) were associated with treatment failure in the unadjusted analysis, the only one that remained predictive on multivariable analysis was prior fracture. Neither of the other two independent predictors in the present analysis (vitality and falls in the past year) is included in FRAX, though falls are included in the Garvan tool.(14)

The occurrence of a fracture in individuals who demonstrate good adherence to AOM is undesirable for both the patient and their physician. However, as no current treatment prevents all fractures, the risk of a single fracture cannot be ruled out; neither does the occurrence of a single fracture necessarily indicate failure to respond to treatment. This is the rationale underlying the recent definition by the IOF of “treatment failure”.(10) In this definition, if only fractures are taken into consideration, ≥2 incident fractures are required before AOM is judged to have failed. Treatment failure in this context does not mean lack of effect of the drugs on bone tissue, but the fact that the main goal of AOM—avoidance of new fractures—is not achieved. Moreover, some of the drugs have not demonstrated efficacy against vertebral fractures, and therefore fail in preventing this kind of fracture. In both cases, the treatment does not fulfill the expectations of either the patient or the clinician. An additional consideration might be that the currently used AOMs have been assessed in populations selected by bone mineral density and this information is not available in our cohort. Therefore, some of the treated individuals might be in the range of osteopenia and, consequently, the efficacy of the drugs is not fully predictable, despite data suggesting that fracture risk in these individuals is also reduced by some of the drugs.(15)

Our present results show some agreement with those from a cohort study involving 179 postmenopausal women on antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis in 12 Spanish hospitals who were followed up for 5 years.(16) In both the Spanish study and in our international study, prior fracture was independently predictive of treatment failure (OR 3.60; 95% CI 1.47–8.82 and OR 2.93; 95% CI 1.81–4.75, respectively), highlighting the fact that a fracture significantly increases the risk of further fractures. The Spanish study also identified 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration <20 ng/mL as an independent predictor of increased risk (OR 3.89; 95% CI 1.55–9.77). Information on vitamin D and bone structure was not collected in GLOW, with the focus being on quality of life rather than on mechanistic features. In GLOW, prior falls also emerged as an independent risk factor for treatment failure; this finding may reflect the large size of the sample, with greater statistical power to detect such a relationship.

A recent Danish study by Abrahamsen et al.(17) reported risk factors associated with incident fractures while on treatment. Whereas prior fracture was less predictive than in our study (one fracture: hazard ratio [HR] 1.17; 95% CI 1.02–1.34; multiple fractures: HR 1.34; 95% CI 1.08–1.67), the number of co-medications (HR 1.04; 95 % CI 1.03–1.06 for each drug), dementia (HR 1.81; 95% CI 1.18–2.78), and ulcer disease (HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.04–2.03) also increased the risk, findings that were not replicated in our present study. In the Danish study, only treatments with alendronate were analyzed and the different nature of the data and fracture outcome may, at least in part, explain the discrepancies with our study.

The reasons underlying treatment failure are diverse. The presence of concomitant disease, for example, makes the profile of patients treated in everyday clinical practice fundamentally different to that of the “selected” populations enrolled in randomized clinical trials.(18) First, the response of bone to antiresorptive drugs in patients treated in real-life practice may, to some degree, diverge from that observed in trial populations. Second, vitamin D concentration, reported as a determinant of AOM efficacy,(16,19) is very often low in a wide range of chronic conditions. Third, when patients are required to take multiple drugs, compliance and adherence often decline dramatically. Fourth, patients treated with AOM are sometimes in a very advanced stage of the disease, with a deep deterioration in bone structure and quality that carries an extremely high fragility, and which is only partially addressed by the drugs. Consequently, the treatments available today may be insufficient to restore normal or near-normal bone mechanical competence. In the treated population, 7.8% of women reported ≥1 incident fracture in 3 years, although the actual incidence of treatment failure in our cohort, considering only the IOF fracture criteria, is relatively low since ≥2 incident fractures were only reported by 73 of 5550 treated women (1.3% in 3 years).

In general fracture incidence for most sites was higher for individuals sustaining ≥2 fractures vs. those with only 1. Statistical significance was reached for several locations (rib, ankle, foot, upper arm, upper leg, pelvis, and elbow) and for the rest there was a numerically higher incidence. Incident fracture of the shoulder was less often reported, however, for patients with ≥2 incident fractures. For the latter, we believe that the small number of events could have resulted in a chance finding. For the rest, and especially for sites with significantly higher incidences, we could speculate that individuals in the ≥2 fracture categories are those with higher risk, as shown in the analysis in which they reported more falls or had reported higher prevalent fractures at baseline. This group therefore sustains more fractures, further underlying the fact that are of especially high risk and are, as a consequence, less responsive to treatment.

The two scales compared, FRAX and Garvan, yield higher risk as the number of incident fractures increase. However, the predicted risk is higher for the Australian than for the WHO algorithms. Although some studies have reported similar moderate predictive ability for the two tools, not superior to age+fracture history (Philip N Sambrook, Julie Flahive, Fred H Hooven, Steven Boonen, Roland Chapurlat, Robert Lindsay, Tuan V Nguyen, Adolfo Diez-Perez, Johannes Pfeilschifter, Susan L Greenspan, David Hosmer, J Coen Netelenbos, Jonathan D Adachi, Nelson B Watts, Cyrus Cooper, Christian Roux, Maurizio Rossini, Ethel S Siris, Stuart Silverman, Kenneth G Saag, Juliet E Compston, Andrea LaCroix, Stephen Gehlbach. Predicting Fractures in an International Cohort Using Risk Factor Algorithms Without BMD. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, Vol. 26, No. 11, November 2011, pp 2770–2777) while Garvan has shown a tred to overestimate risk while FRAX unerestimates in other series (Mark J Bolland,, Amanda TY Siu, Barbara H Mason, Anne M Horne, Ruth W Ames, Andrew B Grey, Greg D Gamble, and Ian R Reid. Evaluation of the FRAX and Garvan Fracture Risk Calculators in Older Women Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, Vol. 26, No. 2, February 2011, pp 420–42). Differences between cohorts and the risk factors included by both scales might account, at least in part, for these discrepant results.

All of these considerations demonstrate the value of ongoing and future research in this area. We probably need more potent regimens or drugs, as well as more specific treatments tailored to the individual needs of different groups of patients. For example, treatment with an AOM, which was developed and tested in selected postmenopausal women with a number of exclusion criteria, may not be a wise strategy for a male patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with respiratory insufficiency, associated heart failure, and impaired renal function, who is receiving multiple drugs (including glucocorticoids) and who has extreme functional limitations causing him to fall frequently. Similarly, for a patient with advanced bone loss and multiple vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, the current options may not be sufficient.

A strength of our study is that gathering “real-life” information from patients treated in everyday clinical practice offers greater external validity to our results when compared with the selected populations included in clinical trials. Our study subjects were non-selected, recruited from 10 different countries, and the same questionnaire was applied throughout the study. The large sample size and the prospective design are also positive elements in terms of reaching statistical significance.

The GLOW study is, however, also subject to certain limitations, including the self-reporting of data, which may be subject to recall bias. The occurrence of fractures was not validated, and vertebral fractures, which are often subclinical, are likely to be under-reported. Moreover, rib fractures were frequent in our cohort, and these are amongst the least severe fragility fractures, although they carry a significant risk increase of further fractures, as observed in the GLOW population.(20) However, by taking into account fractures that are sufficiently clinically relevant to lead to a medical assessment and diagnosis, we are more certain of the clinical relevance of our results.(21) Data on other elements that play a role in the assessment of response to AOM—mainly bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone remodeling—were not collected. However, fracture is likely to be the dominant criterion: it is available in any clinical setting and, without doubt, is the main driver for decision-making about treatment, both for patients and their physicians. Sampling in GLOW was practice- rather than population-based, with additional potential for bias. Compliance was not assessed in detail, although current use and persistence data were recorded. Finally, women who failed to return one or more surveys or who had missing data were excluded from the analysis. However, these limitations do not preclude the robustness of the associations we found between baseline variables and incident fractures while on AOM.

In conclusion, impaired vitality, prior falls, and prior fractures are independent predictors of incident fracture among postmenopausal women on AOM. These findings may help to further define strategies for the prevention of fracture in this population of patients.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to our friend and colleague Professor Steven Boonen, in appreciation of his invaluable contribution to the GLOW study and to the field of osteoporosis in general.

The GLOW study is supported by a grant from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals and sanofi-aventis) to the Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School. We thank the physicians and study coordinators participating in GLOW.

Grant support: Financial support for the GLOW study is provided by Warner Chilcott Company, LLC and sanofi-aventis to the Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Footnotes

Disclosures

AD-P has received consulting fees and lectured for Eli Lilly, Amgen, Procter & Gamble, Servier, and Daiichi-Sankyo; has been an expert witness for Merck; and is a consultant/Advisory Board member for Novartis, Eli Lilly, Amgen, and Procter & Gamble; has received honoraria from Novartis, Lilly, Amgen, Procter & Gamble, and Roche; has been an expert witness for Merck; and has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Novartis, Lilly, Amgen, and Procter & Gamble. JDA has been a consultant/speaker for Amgen, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Roche, sanofi-aventis, Servier, Warner Chilcott and Wyeth; and has conducted clinical trials for Amgen, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Roche, sanofi-aventis, Warner Chilcott, Wyeth, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. SA has received speaker honoraria from Eli-Lilly and Amgen; and consultancy honoraria from MSD, Eli-Lilly, Amgen and Novartis. FAA has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott). SB has received research grants from Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline; and has received honoraria from, served on Speakers’ Bureaus for, and acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Amgen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, and Servier. RC has received funding from the French Ministry of Health, Merck, Servier, Lilly, and Procter & Gamble; has received honoraria from Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Lilly, Roche, and sanofi-aventis; and has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Amgen, Merck, Servier, Nycomed, and Novartis. JEC has undertaken paid consultancy work for Servier, Shire, Nycomed, Novartis, Amgen, Procter & Gamble, Wyeth, Pfizer, The Alliance for Better Bone Health, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline; has been a paid speaker for and received reimbursement, travel and accommodation from Servier, Procter & Gamble, and Lilly; and has received research grants from Servier R&D and Procter & Gamble. CC has received consulting fees from and lectured for Amgen, The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott), Lilly, Merck, Servier, Novartis, and Roche-GSK. SHG has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott). SLG has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Amgen, Lilly, and Merck; and has received research grants from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Proctor & Gamble) and Lilly. FHH has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott). AZL has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott) and is an Advisory Board member for Amgen. JWN has no disclosures. JCN has undertaken paid consultancy work for Roche Diagnostics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Proctor & Gamble, and Nycomed; has been a paid speaker for and received reimbursement, travel and accommodation from Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Procter & Gamble; and has received research grants from The Alliance for Better Bone Health and Amgen. JP has received research grants from Amgen, Kyphon, Novartis, and Roche; has received other research support (equipment) from GE Lunar; has served on Speakers’ Bureaus for Amgen, sanofi-aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Lilly Deutschland, Orion Pharma, Merck, Merckle, Nycomed, and Procter & Gamble; and has acted as an Advisory Board member for Novartis, Roche, Procter & Gamble, and Teva. MR is on the Speaker’ Bureau for Roche. CR has received honoraria from and acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Alliance, Amgen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Nycomed, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Servier, and Wyeth. KGS received consulting fees or other remuneration from Eli Lilly & Co, Merck, Novartis, and Amgen; and has conducted paid research for Eli Lilly & Co, Merck, Novartis, and Amgen. SS has received research grants from Wyeth, Lilly, Novartis, and Alliance; has served on Speakers’ Bureaus for Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Procter & Gamble; has received honoraria from Procter & Gamble; and has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Lilly, Argen, Wyeth, Merck, Roche, and Novartis. ESS has acted as a consultant for Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, and The Alliance for Better Bone Health; and has served on Speakers’ Bureaus in the past year for Amgen, and Lilly. AW has no disclosures. SKR-S reported consultancy for the European Society of Cardiology, Genzyme, Medtronic, sanofi-aventis, and Servier; and receiving honoraria from Servier.

Authors’ roles: Study design: ADP, JDA, SA, FAA, SB, RC, JEC, CC, SHG, SLG, FHH, AZL, JWN, JCN, JP, MR, CR, KGS, SS, ESS, NBW. Study conduct: ADP, JDA, SA, FAA, SB, RC, JEC, CC, SHG, SLG, FHH, AZL, JWN, JCN, JP, MR, CR, KGS, SS, ESS, NBW. Data collection: ADP, JDA, SA, SB, RC, CC, SLG, AZL, JWN, JCN, JP, MR, CR, KGS, SS, NBW. Data analysis: AW. Data interpretation: ADP. Drafting manuscript: ADP. Revising manuscript content: ADP, SRS. Approving final version of manuscript: ADP, JDA, SA, FAA, SB, RC, JEC, CC, SHG, SLG, FHH, AZL, JWN, JCN, JP, MR, CR, KGS, SS, ESS, AW, SRS, NBW. AW takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

References

- 1.MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Mojica W, Timmer M, Alexander A, McNamara M, Desai SB, Zhou A, Chen S, Carter J, Tringale C, Valentine D, Johnsen B, Grossman J. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Annals of internal medicine. 2008;148(3):197–213. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-3-200802050-00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nickelsen T, Genant HK, Christiansen C, Delmas PD, Zanchetta JR, Stakkestad J, Gluer CC, Krueger K, Cohen FJ, Eckert S, Ensrud KE, Avioli LV, Lips P, Cummings SR, Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(7):637–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levis S, Quandt SA, Thompson D, Scott J, Schneider DL, Ross PD, Black D, Suryawanshi S, Hochberg M, Yates J, FIT Research Group Alendronate reduces the risk of multiple symptomatic fractures: results from the fracture intervention trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50(3):409–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts NB, Josse RG, Hamdy RC, Hughes RA, Manhart MD, Barton I, Calligeros D, Felsenberg D. Risedronate prevents new vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;88(2):542–549. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackey DC, Black DM, Bauer DC, McCloskey EV, Eastell R, Mesenbrink P, Thompson JR, Cummings SR. Effects of antiresorptive treatment on nonvertebral fracture outcomes. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26(10):2411–2418. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, Vukicevic S, Zanchetta JR, de Villiers TJ, Constantine GD, Chines AA. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2008;23(12):1923–1934. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z, Mautalen C, Mesenbrink P, Hu H, Caminis J, Tong K, Rosario-Jansen T, Krasnow J, Hue TF, Sellmeyer D, Eriksen EF, Cummings SR, HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356(18):1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, Delmas P, Zoog HB, Austin M, Wang A, Kutilek S, Adami S, Zanchetta J, Libanati C, Siddhanti S, Christiansen C, FREEDOM Trial Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(8):756–765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diez-Perez A, Gonzalez-Macias J. Inadequate responders to osteoporosis treatment: proposal for an operational definition. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2008;19(11):1511–1516. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diez-Perez A, Adachi JD, Agnusdei D, Bilezikian JP, Compston JE, Cummings SR, Eastell R, Eriksen EF, Gonzalez-Macias J, Liberman UA, Wahl DA, Seeman E, Kanis JA, Cooper C, IOF CSA Inadequate Responders Working Group Treatment failure in osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2012;23(12):2769–2774. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooven FH, Adachi JD, Adami S, Boonen S, Compston J, Cooper C, Delmas P, Diez-Perez A, Gehlbach S, Greenspan SL, LaCroix A, Lindsay R, Netelenbos JC, Pfeilschifter J, Roux C, Saag KG, Sambrook P, Silverman S, Siris E, Watts NB, Anderson FA., Jr The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW): rationale and study design. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2009;20(7):1107–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0958-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2008;19(4):385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garvan Institute. Fracture Risk. http://www.garvan.org.au/bone-fracture-risk. Accessed: 15 April 2013.

- 15.Levis S, Theodore G. Summary of AHRQ’s comparative effectiveness review of treatment to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis: update of the 2007 report. Journal of managed care pharmacy: JMCP. 2012;18(4 Suppl B):S1–15. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.s4-b.1. discussion S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diez-Perez A, Olmos JM, Nogues X, Sosa M, Diaz-Curiel M, Perez-Castrillon JL, Perez-Cano R, Munoz-Torres M, Torrijos A, Jodar E, Del Rio L, Caeiro-Rey JR, Farrerons J, Vila J, Arnaud C, Gonzalez-Macias J. Risk factors for prediction of inadequate response to antiresorptives. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(4):817–824. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrahamsen B, Rubin KH, Eiken PA, Eastell R. Characteristics of patients who suffer major osteoporotic fractures despite adhering to alendronate treatment: a National Prescription registry study. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2013;24(1):321–328. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowd R, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Study subjects and ordinary patients. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2000;11(6):533–536. doi: 10.1007/s001980070097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adami S, Isaia G, Luisetto G, Minisola S, Sinigaglia L, Gentilella R, Agnusdei D, Iori N, Nuti R, ICARO Study Group Fracture incidence and characterization in patients on osteoporosis treatment: the ICARO study. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2006;21(10):1565–1570. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzgerald G, Boonen S, Compston JE, Pfeilschifter J, Lacroix AZ, Hosmer DW, Jr, Hooven FH, Gehlbach SH, GLOW Investigators Differing risk profiles for individual fracture sites: Evidence from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women (GLOW) Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(9):1907–1915. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burger H, Van Daele PL, Grashuis K, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, Schutte HE, Birkenhager JC, Pols HA. Vertebral deformities and functional impairment in men and women. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1997;12(1):152–157. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]