Abstract

Prostaglandin (PG) endoperoxide H synthase (PGHS)-2, also known as cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, can convert arachidonic acid (AA) to PGH2 in the committed step of PG synthesis. PGHS-2 functions as a conformational heterodimer composed of an allosteric (Eallo) and a catalytic (Ecat) monomer. Here we investigated the interplay between human (hu)PGHS-2 and an alternative COX substrate, the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), as well as a stable analog, 2-O-arachidonylglycerol ether (2-AG ether). We also compared the inhibition of huPGHS-2-mediated oxygenation of AA, 2-AG, and 2-AG ether by the well-known COX inhibitor, ibuprofen. When tested with huPGHS-2, 2-AG and 2-AG ether exhibit very similar kinetic parameters, responses to stimulation by FAs that are not COX substrates, and modes of inhibition by ibuprofen. The 2-AG ether binds Ecat more tightly than Eallo and, thus, can be used as a stable Ecat-specific substrate to examine certain Eallo-dependent responses. Ibuprofen binding to Eallo of huPGHS-2 completely blocks 2-AG or 2-AG ether oxygenation; however, inhibition by ibuprofen of huPGHS-2-mediated oxygenation of AA engages a combination of both allosteric and competitive mechanisms.

Keywords: cyclooxygenase-2; prostaglandin, half-sites; 2-arachindonoylglycerol; arachidonic acid; palmitic acid; ibuprofen

Prostaglandin (PG) endoperoxide synthase (PGHS)-1 and PGHS-2 catalyze the formation of PGH2 from arachidonic acid (AA) in the committed step of PG biosynthesis (1–4). PGHS-1 and PGHS-2 are considered to be the constitutive and inducible PGHS isoforms, respectively. PGHSs are often called cyclooxygenases (COXs). Both enzymes exhibit a bis-oxygenase or COX activity involved in the formation of the PG endoperoxide G2 and a peroxidase activity that reduces PG endoperoxide G2 to PGH2. COX activities of PGHSs are inhibited by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that include COX-2-specific inhibitors, sometimes referred to as coxibs (5).

PGHSs are sequence homodimers composed of 72 kDa subunits. Despite the structural symmetry observed in crystal structures, both PGHS isoforms behave in solution as conformational heterodimers. One monomer (Eallo) acts as a regulatory allosteric monomer, and the other monomer (Ecat) binds heme and functions as the catalytic monomer (6–8). The COX activity of Ecat of human (hu)PGHS-2 is allosterically modulated by many common FAs, including saturated and monounsaturated FAs that are not COX substrates [e.g., palmitic acid (PA)] (9, 10), and by some nonspecific NSAIDs, such as flurbiprofen and naproxen (7), that bind preferentially to Eallo of huPGHS-2.

Marnett and coworker (3) were the first to demonstrate that the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), is an alternative substrate that is converted to 2-PGH2-glycerol by PGHS-2. This latter intermediate can, in turn, be converted to several different 2-prostanoyl-glycerol derivatives. A recent report has indicated that 2-AG binds with higher affinity to Ecat than Eallo of murine (mu)PGHS-2 (11); in contrast, AA binds with much higher affinity to Eallo than Ecat (7). Interestingly, a nonsubstrate (ns)FA, 13-methyl AA, increases the rate of oxygenation of 2-AG by muPGHS-2 by increasing the Vmax, but not the Km, toward 2-AG (11).

The 2-AG is unstable and readily rearranges to 1-AG and hydrolyzes to AA and glycerol (12). This instability presents experimental difficulties in studying the interactions of 2-AG with PGHSs. The 2-O-arachidonylglycerol ether (2-AG ether) is a stable analog of 2-AG. In the first part of the present study, we report the characterization of 2-AG ether as a substrate of huPGHS-2. We find that the 2-AG ether behaves very much like 2-AG with huPGHS-2. Because of its stability, 2-AG ether can serve as a surrogate for 2-AG in enzyme studies.

In related work described here, we examined the ability of the commonly used NSAID, (S)-(+)-ibuprofen (IBP), to interact with Eallo and Ecat to inhibit huPGHS-2. We confirm results of earlier studies that IBP is an allosteric inhibitor of 2-AG oxygenation (13) and extend this finding to 2-AG ether. We also observed that IBP binding to Eallo of huPGHS-2 allosterically inhibits AA oxygenation, but does so only incompletely. Complete inhibition involves the binding of IBP to both Ecat and Eallo of huPGHS-2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Complete protease inhibitor was from Roche Applied Science. Ni-NTA Superflow resin and Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid were from Qiagen. PA (16:0), oleic acid (18:1ω9), stearic acid (18:0), 11-eicosaenoic acid (20:1ω9), FLAG peptide, and FLAG affinity resin were from Sigma-Aldrich. AA, 2-AG, and 2-AG ether were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Hemin was from Frontier Scientific, Logan, UT. IBP was from Tocris Bioscience. The [1-14C]AA (1.85 GBq/mmol) was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Decyl maltoside, n-octyl β-D-glucopyranoside, and C10E6, used in protein purification, were purchased from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). BCA protein reagent was from Pierce. Hexane, isopropyl alcohol, and acetic acid were HPLC grade from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Anti-PGHS-2 antibodies directed against the 18-amino acid insert unique to PGHS-2 were as described (14). Anti-FLAG antibodies were from LifeTein, South Plainfield, NJ. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG) were from Bio-Rad.

Expression, purification, and assay of huPGHS-2 variants

Procedures for the expression and purification of recombinant native huPGHS-2 and mutant huPGHS-2 heterodimer variants from insect cells were as described previously (7, 15). The purity of the recombinant huPGHS-2 was determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis (9). In most cases, COX activity was determined using measurements of O2 consumption with an O2 electrode (7). One unit of COX activity is defined as 1 μmol of O2 consumed per minute at 37°C in the standard assay mixture. The average specific activity of purified huPGHS-2 with 100 μM AA was 40 units per milligram protein. This specific activity is similar to that reported in earlier studies from our laboratory using different lots of purified huPGHS-2 (i.e., within ±5%) (7, 10, 15).

COX assays at high enzyme-to-substrate ratios to test for ligand binding to Eallo

Briefly, COX assays were performed at high enzyme/[1-14C]AA ratios in order to quantify [1-14C]AA binding to Eallo of huPGHS-2. Unlabeled ligands (e.g., PA, 2-AG, and 2-AG ether) were tested for their abilities to displace unreacted [1-14C]AA remaining bound to Eallo. Reaction mixtures (100 μl final volume) containing 1 μM [1-14C]AA, 0.10–2.0 μM huPGHS-2, 5 μM hematin, and 1 mM phenol in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) were incubated at 37°C for 1–8 min, and the products were separated and quantified by radio-reverse-phase (RP)-HPLC, as detailed previously (7, 10). The principle underlying this method is described in (10). Agents that displace [1-14C]AA from Eallo of huPGHS-2 cause the disappearance of [1-14C]AA, which, following its displacement from Eallo, is converted by Ecat to an oxygenated product.

Structural analysis of products formed upon oxygenation of 2-AG ether by huPGHS-2

A reaction was performed using a standard COX assay mixture that included 20 μg of 2-AG ether as the substrate and sufficient huPGHS-2 to consume approximately 80% of the substrate during a 2 min incubation. Immediately afterwards, a volume of 100 mM SnCl2 in methanol was added to the sample such that the final SnCl2 concentration was 1 mM. The sample was vortexed and incubated at room temperature, then extracted with ethyl acetate, dried under N2, and kept in a sealed tube until analyzed. Control reactions were performed with assay buffer alone, with assay buffer that included heme and phenol, with huPGHS-2 in buffer alone, with huPGHS-2 in buffer that included heme and phenol, with 2-AG ether in buffer alone, with 2-AG ether in buffer containing heme and phenol, and with 2-AG ether plus huPGHS-2 in buffer alone.

Acetylation of the extracted reaction products was performed with a 1:1 mixture of acetic anhydride and pyridine for 20 min at 100°C. The reaction mixture was dried under nitrogen, dissolved in methanol, and then diluted with water to a final methanol concentration of less than 15%. Solid phase extraction and reversed phase chromatography were performed essentially as previously described (16). The LC effluent was directly interfaced into the electrospray ionization source of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex API 5500; PE-Sciex, Thornhill, ON, Canada) where mass spectrometric analyses were performed in the positive ion mode (m/z 250–800) or as MS2 product ions using nitrogen as collision gas at a collision voltage of 25 V. TMS ether derivatives were prepared from HPLC-purified metabolites and analyzed by electron ionization by capillary GC/MS, as previously described (17), using a Finnigan DSQ GC-MS system (Thermo Finnigan, Thousand Oaks, CA) with a ZB-l column (30 m, 0.25 mm inner diameter 0.25 mm film thickness; Phenomenex). The gas chromatograph was programmed from 150 to 270°C at 30°C/min, 270 to 315°C at 10°C/min, and finally held at 315°C for 6 min. The injector was maintained at 230°C, the transfer line was maintained at 290°C, and the ion source at 200°C.

Statistical analyses

Student’s t-tests were performed in Microsoft Excel. If the experiments had the same numbers of repetitions, probabilities were calculated with a Student’s paired t-test, with a two-tailed distribution. If the experiments had different numbers of repetitions, probabilities were calculated with a Student’s unequal variance t-test, with a two-tailed distribution.

RESULTS

Products formed from 2-AG ether by huPGHS-2

When 2-AG ether (75 nmoles) was incubated with an excess of huPGHS-2 (240 nmoles) at 37°C in a standard COX assay mixture for 2 min, 112 nmoles of O2 were consumed. We assumed that the excess enzyme led to complete conversion of the substrate and that either one or two O2 molecules were incorporated into the 2-AG ether substrate. These assumptions were corroborated by the mass spectrometric results described below. Accordingly we calculated that 1.49 mol O2 were incorporated per mole of 2-AG ether, indicating that about 70% of the products were bis-oxygenated (i.e., 2-PGH2-glycerol ether) and 30% were mono-oxygenated [i.e., 2-(hydroxy-eicosatetraenoyl)-glycerol ether(s)].

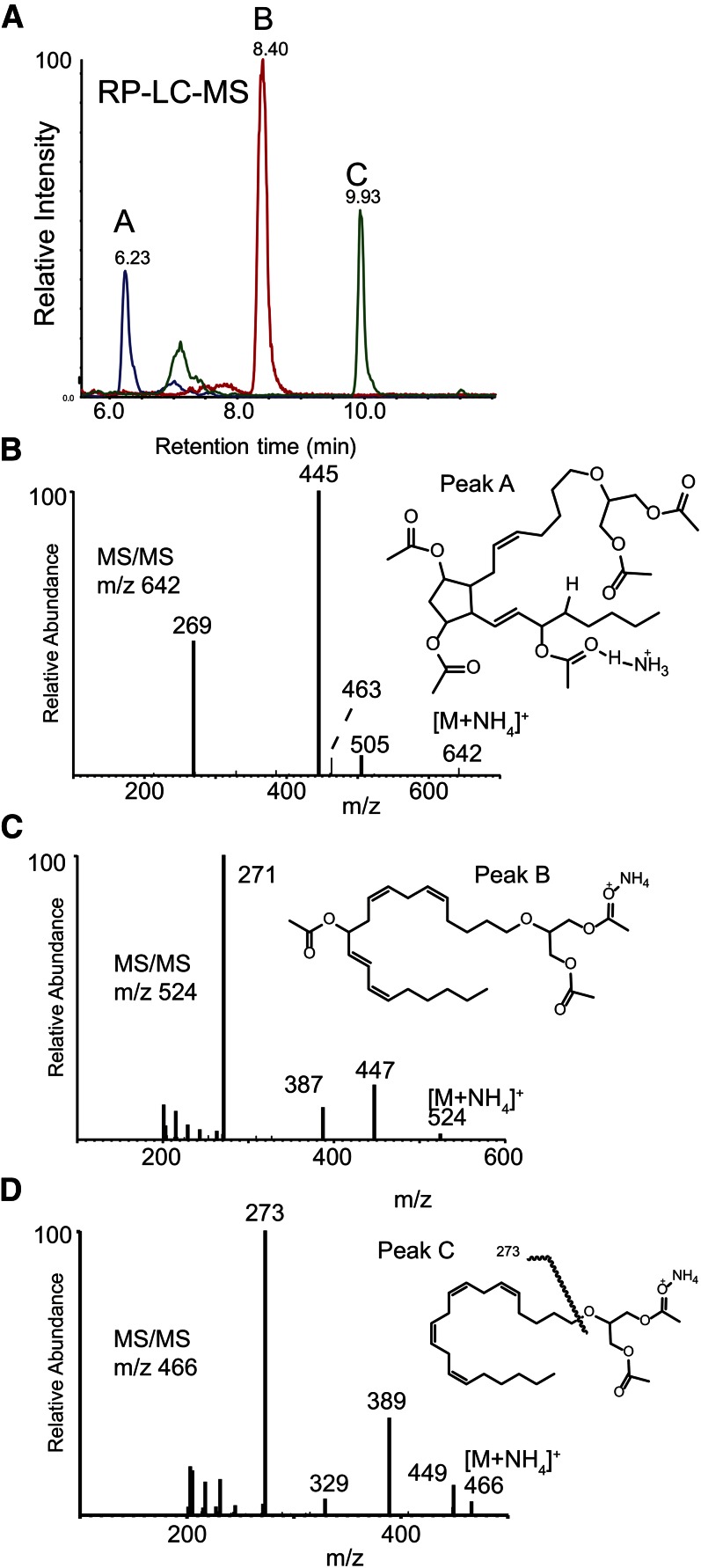

Mass spectrometric studies using LC-MS and LC-MS/MS were performed to directly characterize the structural products obtained following the action of huPGHS-2 on 2-AG ether (Fig. 1). In order to impart favorable mass spectrometric characteristics, the products extracted from the reaction mixture were first reduced with SnCl2 and then derivatized by acetylation. RP-HPLC was able to separate two less lipophilic products from the starting 2-AG ether that were not present in control incubations with huPGHS-2 when no phenol or heme was present (Fig. 1A). These are labeled peak A and the more lipophilic peak B. Because these were presumed to be acetylated ether diglycerides, positive ion electrospray ionization as the ammonium adduct ion (NH4+) was employed. The observed [M+NH4]+ adduct ions were m/z 642 (peak A; Fig. 1B) and m/z 524 (peak B; Fig. 1C), while the signal for unreacted starting material was found to produce m/z 466 (peak C; Fig. 1D). Collisional activation of the starting material (peak C) yielded a major product ion at m/z 273 corresponding to cleavage of the arachidonyl chain at the ether bond (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Structural analysis of products formed by the oxygenation of 2-AG ether by huPGHS-2. A: RP-HPLC separation and electrospray (positive ions) MS of reaction products of 2-AG with huPGHS-2. Peaks labeled A (blue), B (red), and C (green) were found to have molecular ions [M+NH4]+ at m/z 642, 524, and 466, respectively. B: Collisional activation of m/z 642 (peak A). Structure inset with origin of major product ion indicated as the acetate derivative. C: Collisional activation of m/z 524 (peak B). Structure inset of proposed metabolite indicated as the acetate derivative. D: Collisional activation of m/z 466 (starting material, peak C). Structure inset of proposed monoacetate adduct indicated.

The spectrum of least lipophilic reaction product (acetyl derivative, ammonium ion adduct, m/z 642) (Fig. 1B) was consistent with the addition of 3-hydroxyl groups (analyzed as acetyl esters) and reduction of one double bond. This was consistent with a PGF2-like structure generated from a PGH2 endoperoxide intermediate formed by the COX activity of huPGHS-2 acting on the arachidonyl ether chain of 2-AG ether. The collisional activation of m/z 642 [M+NH4]+ yielded a very prominent product ion at m/z 445 (Fig. 1B), consistent with three neutral losses of acetic acid (60 Da each) and ammonia (NH3). The abundant ion at m/z 269 could then be understood as cleavage of the arachidonyl carbon-ether bond with positive charge retention on the 20-carbon alkyl leaving group via the mechanism suggested in supplementary Fig. 1. The corresponding ether-bond fragment ion was observed in the MS/MS spectra of peaks B and C, but each was 2 Da and 4 Da, respectively, higher in measured m/z because the alkyl carbocation generated by collisional activation (supplementary Fig. 1) has five and six rings or double bonds, respectively, compared with the arachidonyl carbocation generated from CID of 2-AG ether, which has only four rings or double bonds. Considering the presence of three hydroxyl groups and loss of a double bond, the data are consistent with the presence of a novel ether lipid having a PGF2 structural element, 2-O-(PGF2)-glycerol. The scale employed in these experiments was not sufficient for NMR analysis of this metabolite.

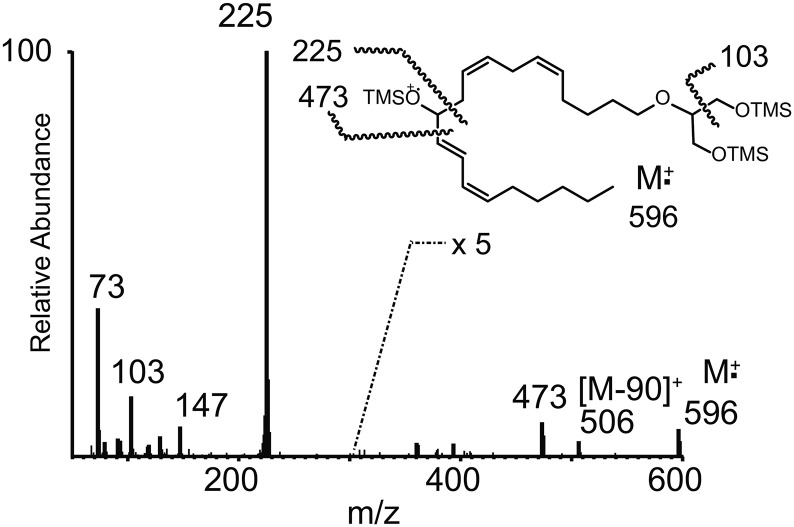

The increase in the observed adduct molecular ion mass for peak B was 58 Da (Fig. 1C), consistent with one additional hydroxyl group along the arachidonyl carbon chain that had been converted to an acetate ester. Collisional activation of peak B yielded ions at m/z 447 [M+H-CH3COOH]+, m/z 387 (m/z 477-CH3COOH), and the most abundant product ion at m/z 271 (Fig. 1C). This latter ion corresponded to the most abundant product ion observed in the MS/MS spectrum of the starting material (that being m/z 273), but 2 Da lower, corresponding to cleavage of the ether bond in 2-AG ether and one additional double bond introduced by the presence of one acetoxy group that had been lost as acetic acid following collisional activation. The position of this hydroxyl group on the 20-carbon chain was determined by electron ionization MS as the TMS derivative (Fig. 2), and the ion at m/z 225 [CH3(CH2)4CH=CH-CH=CH-CH=O+-TMS] was consistent with an introduction of a hydroxyl group at C-11 of the arachidonoyl carbon chain and migration of the Δ11,12 double bond to Δ12,13. Thus, this metabolite was determined to be 2-O-(11-hydroxy-eicosatetraenyl)-glycerol.

Fig. 2.

EI mass spectrum of the TMS-derivative of peak B obtained by GC/MS. Structure inset with origin of major EI ions indicated from the TMS derivative.

Overall, our mass spectrometric studies and measurements of O2 consumption indicate that 2-AG ether is converted by huPGHS-2 to two major products: 2-O-(11-hydroxy-eicosatetraenyl)-glycerol ether (25%) and 2-O-(PGH2)-glycerol ether (75%). These two products are the glycerol ether homologs of the 2-(11-hydroxy-eicosatetraenoyl)-glycerol and 2-PGH2-glycerol products that are formed in similar proportions upon incubation of 2-AG with muPGHS-2 (18).

Comparison of 2-AG and 2-AG ether as huPGHS-2 substrates

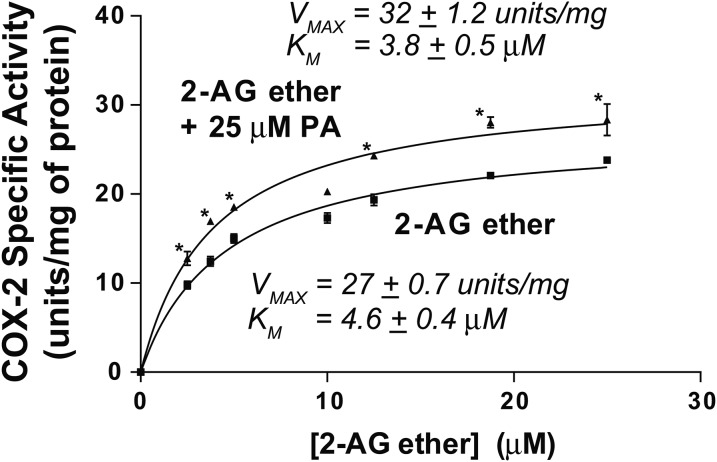

We determined the following Vmax and Km values for recombinant huPGHS-2 when comparing 2-AG ether, 2-AG, and AA as substrates: Vmax of 27 units/mg and Km = 4.6 μM for 2-AG ether (Fig. 3); Vmax of 30 units/mg and Km ∼7 μM for 2-AG (15); and Vmax of 43 units/mg and Km ∼10 μM for AA (15). Thus, the catalytic efficiencies (Vmax/Km) with huPGHS-2 are similar when each substrate is tested individually.

Fig. 3.

Oxygenation of 2-AG ether by huPGHS-2 in the presence and absence of PA. Results are shown as rates of O2 consumption determined by measuring COX activity using an O2 electrode as described in the Experimental Procedures. Reactions were initiated by adding an aliquot of purified native huPGHS-2 to an assay chamber containing the indicated concentration of 2-AG ether in the absence or presence of 25 μM PA. Experiments were performed with at least two different preparations of huPGHS-2 with similar results. Results are shown for a representative experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± SD. Asterisks denote significant differences between the specific activity without PA versus with 25 μM PA at the indicated 2-AG ether concentration, as determined by the Student’s t-test (P < 0.01).

To estimate the relative affinities of Eallo versus Ecat of huPGHS-2 for 2-AG ether, we first examined the effects of the nsFA, PA, on the oxygenation of 2-AG ether (Fig. 3). Increasing the ratio of 2-AG ether to PA did not change the ratio of the rates with 2-AG ether alone versus 2-AG ether plus PA. This indicates that 2-AG at any of the concentrations used in the assays fails to compete with 25 μM PA for Eallo. PA binds to Eallo of huPGHS-2 with a Kd ∼7.5 μM, but binds only very weakly to Ecat (Kd >50 μM) (7). PA increased the Vmax, but did not change the Km, of huPGHS-2 for 2-AG ether. Because it increases the rate of 2-AG ether oxygenation, PA is not competing for Ecat, but rather must act via Eallo; moreover, 2-AG ether did not compete with PA for Eallo at the concentrations tested. This indicates that 2-AG ether binds significantly less tightly to Eallo than PA, and thus, less tightly to Eallo than Ecat. The Kd for PA binding to Eallo is ∼7.5 μM, which is below its critical micelle concentration [∼25 μM (7, 9)], where PA effectively binds only Eallo. The 2-AG ether did not displace PA from Eallo when the ratio of 2-AG ether/PA was 1.0, indicating that the Kd for 2-AG ether binding is significantly greater than 7.5 μM and, thus, greater than the Kd of 2-AG ether for Ecat. The Kd for 2-AG ether binding to Ecat is the Km of huPGHS-2 for 2-AG [∼5 μM (Fig. 3)]. This situation is unlike what is observed with AA (7) or EPA (10) that bind Eallo 30 times more tightly than Ecat of huPGHS-2.

The results in Table 1 provide further evidence that 2-AG ether binds more tightly to Ecat than Eallo of huPGHS-2. In contrast to what is observed with PA or with 5 μM AA itself, 2-AG ether, at an initial concentration of 5 μM, more than 25 times that of unreacted [1-14C]AA (0.18 μM), failed to displace [1-14C]AA from Eallo of huPGHS-2. Only at concentrations higher than 7.5 μM does 2-AG ether cause any significant displacement of [1-14C]AA from Eallo. These findings provide additional evidence that 2-AG ether fails to bind efficiently to Eallo of PGHS-2.

TABLE 1.

RP-HPLC analysis of the displacement of [1-14C]AA from Eallo of huPGHS-2 by unlabeled AA, PA, or 2-AG ether

| FA Addeda | Unreacted [1-14C]AA Remainingb,c |

| Control (no FA added) | 18 ± 0.08 |

| 5 μM AA | 6.6 ± 1.4d |

| 5 μM PA | 6.2 ± 1.2d |

| 2.5 μM 2-AG ether | 17 ± 0.22 |

| 5 μM 2-AG ether | 16 ± 0.33 |

| 7.5 μM 2-AG ether | 14 ± 0.09 |

| 15 μM 2-AG ether | 11 ± 0.09d |

| 25 μM 2-AG ether | 7.9 ± 1.8d |

The [1-14C]AA (1 μM) was incubated with huPGHS-2 (1 μM) at 37°C for 4 min, then unlabeled AA, PA, or 2-AG ether was added, and the incubation continued for another 4 min. Reactions were stopped by adding ethyl acetate/acetic acid (20:1), and an aliquot of the organic phase was subjected to radio-RP-HPLC to separate the radioactive products and unreacted AA, as described in the Experimental Procedures. The results are shown as the percentage of total 14C label that remained in the RP-HPLC fraction co-eluting with unreacted AA; the data represent averages of replicate samples ± SD. The results are shown for a single experiment that was performed a total of three times with similar results using different enzyme preparations in each case and concentrations of 2-AG ether ranging from 2.5–50 μM.

FA was added 4 min after initiating the reaction.

The amount of unreacted [1-14C]AA remaining after 8 min (percent of starting radioactivity, average ± SD from two reactions).

Value shown is average ± SD for replicate determinations from one experiment representative of three separate experiments with different preparations of enzyme.

Significantly different from the control value (no FA or other agent added at 4 min) in Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

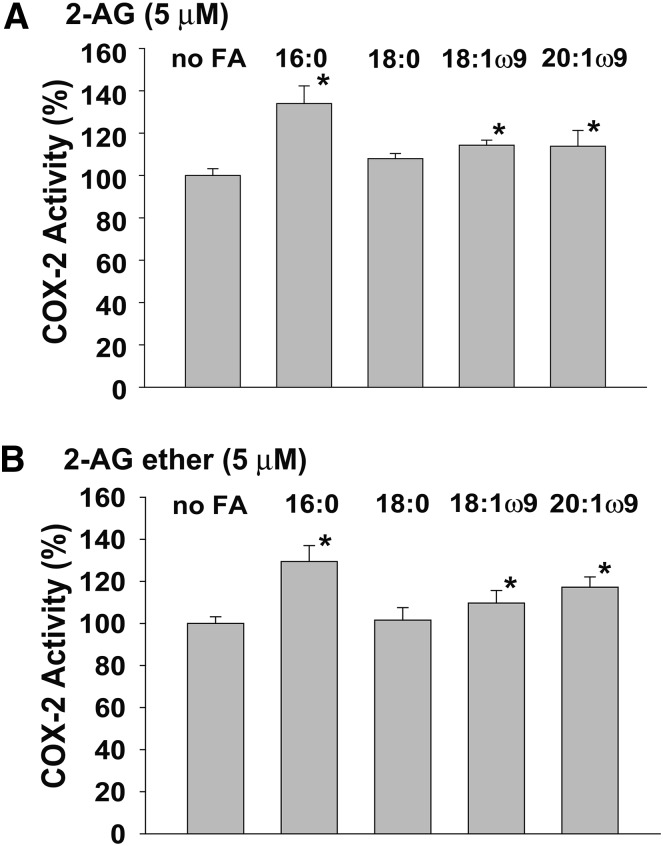

We also compared the interactions of 2-AG and 2-AG ether with nsFAs (Fig. 4). PA was previously found to activate the oxygenation of 2-AG by huPGHS-2, although the magnitude of the effect was much less than that seen with AA (15). As shown in Fig. 4, nsFAs that bind to Eallo cause very similar levels of activation of both 2-AG and 2-AG ether oxygenation by huPGHS-2. These data, viewed in the context of the kinetic data indicating that 2-AG and 2-AG ether have similar properties as huPGHS-2 substrates, establish that 2-AG ether can be used as a stable surrogate for 2-AG in monitoring interactions between this latter endocannabinoid and PGHS-2.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the effects of nsFAs on the oxygenation of 2-AG and 2-AG ether by huPGHS-2. Measurements of COX activity were performed in a standard O2 electrode assay with 5 μM 2-AG (A) or 5 μM 2-AG ether (B) as the substrate in the presence or absence of 25 μM PA (16:0), stearic acid (18:0), oleic acid (18:1ω9), or eicosaenoic acid (20:1ω9), as described in the Experimental Procedures. The same amounts of enzyme protein were used in all assays, and the value without a nsFA was normalized to 100%. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± SD. Asterisks denote significant differences from the value without a nsFA, as determined by the Student’s t-test (P < 0.03).

Comparison of IBP as an inhibitor of the oxygenation of 2-AG, 2-AG ether, and AA

Many COX inhibitors are time-dependent inhibitors, but IBP is a rapidly reversible inhibitor of AA oxygenation (19, 20). As first reported by Marnett and coworkers, IBP is a more potent inhibitor of the oxygenation of 2-AG than of AA by muPGHS-2 (13). According to their model, IBP binds one monomer of PGHS-2 to allosterically inhibit 2-AG oxygenation occurring in the partner catalytic monomer, whereas IBP binding to both monomers is required to inhibit AA oxygenation.

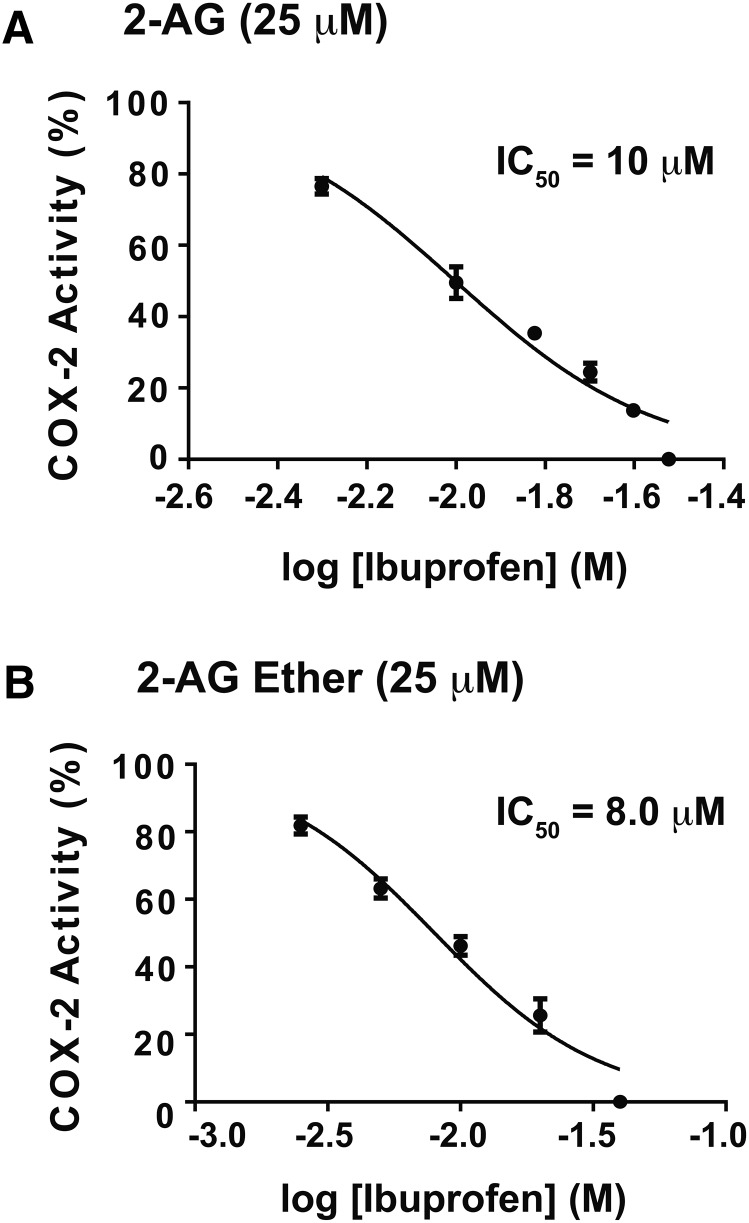

We compared the effects of IBP on the oxygenation of 2-AG, 2-AG ether, and AA by huPGHS-2. As shown in Fig. 5, instantaneous inhibition of huPGHS-2-mediated oxygenation of 2-AG and 2-AG ether occurs at similar concentrations of IBP.

Fig. 5.

Instantaneous inhibition of huPGHS-2-mediated oxygenation of 2-AG and 2-AG ether by IBP. The indicated concentrations of ibuprofen were present in a standard O2 electrode assay mixture along with 25 μM 2-AG (A) or 25 μM 2-AG ether (B) as COX substrates. Purified huPGHS-2 was added to initiate oxygenation reactions. O2 consumption was monitored as described in the Experimental Procedures. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± SD. When control values are normalized to 100% activity, significant differences from the control value (with no ibuprofen) were seen at all the ibuprofen concentrations tested, as determined by the Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). IC50 values shown in the two panels were calculated using GraphPad Prism software. For the monophasic mode shown in the two panels in this figure, IC50 values were calculated by using nonlinear regression to fit the data to the log [ibuprofen] versus normalized response (variable slope) curve.

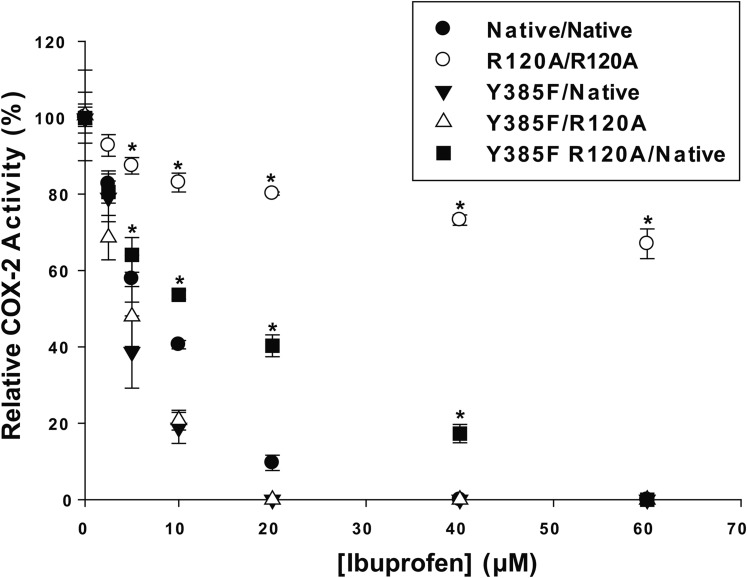

We recently described a recombinant huPGHS-2 heterodimer variant, denoted as Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (15). This variant has 90% of the activity of native huPGHS-2, indicating that 90% of Eallo monomers bear the Tyr385Phe mutation and 90% of Ecat monomers are native monomers; moreover, once Eallo and Ecat of huPGHS-2 are formed, they do not interconvert (15). This variant can be used as a platform to determine the effect of amino acid substitutions in the COX binding site of Eallo, the subunit with the Tyr385Phe substitution, as compared with the native Ecat subunit (15). Figure 6 presents the results of studies of Arg-120 substitutions in the Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 platform on the effect of IBP on 2-AG ether oxygenation; supplementary Fig. 2 presents these data, showing actual rates as opposed to the relative COX activities shown in Fig. 6. Arg-120 is the residue that interacts with the carboxylate group on substrates and inhibitors that bind within the COX active site. Inhibition of oxygenation of 2-AG ether by IBP is largely impeded by having Arg-120 substitutions in both subunits (R120A/R120A huPGHS-2), but only modestly attenuated by having an Arg120Ala substitution in Eallo (i.e., Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2). This suggests that IBP functions by binding Eallo in native huPGHS-2 to cause near complete allosteric inhibition of 2-AG ether oxygenation. However, IBP appears to bind only slightly less well to Ecat to cause complete inhibition when IBP cannot bind to Eallo (i.e., in Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2).

Fig. 6.

Instantaneous inhibition by IBP of 2-AG ether oxygenation by huPGHS-2 variants having an Arg-120 substitution in Eallo or Ecat. Assays of O2 consumption using an O2 electrode were performed as described in the Experimental Procedures using 50 μM 2-AG ether as the substrate. huPGHS-2 heterodimer variants were described previously (15). The designations indicate the mutations in the subunits. For example, Y385F R120A/Native indicates a PGHS-2 molecule having one subunit with both Y385F and R120A mutations and the other subunit as having no mutations (i.e., a Native subunit). R120A/R120A indicates a PGHS-2 molecule with mutations in both subunits. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± SD. Control values for each enzyme variant are normalized to 100%. Asterisks denote a significant difference between the value with inhibitor and the control (native) value with the same level of inhibitor as determined by the Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). Specific activities for the huPGHS-2 variants with 2-AG ether were as follows: for Native, 25 units/mg; for R120A/R120A, 17 units/mg; for Y385F/Native, 19 units/mg; for Y385F R120A/Native, 24 units/mg; and for Y385F/R120A, 22 units/mg.

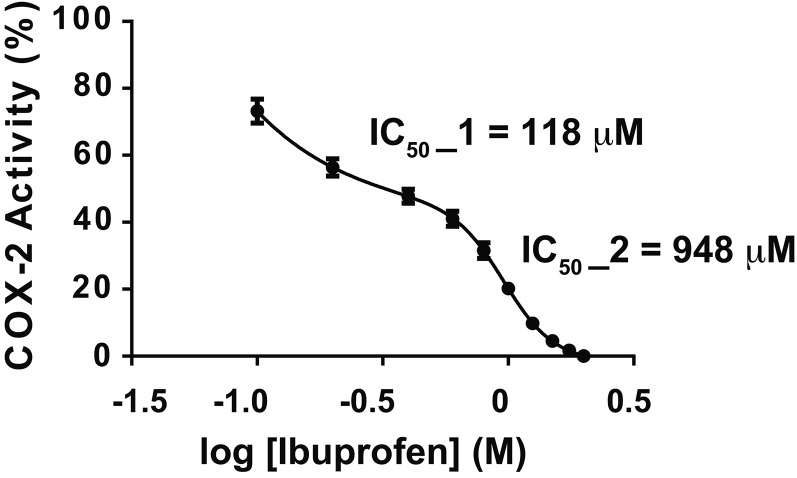

As shown in Figs. 5, 6, 50% inhibition of 2-AG ether oxygenation occurs with 5–10 μM IBP with essentially complete inhibition occurring with 30–40 μM IBP. As illustrated in Fig. 5 with native huPGHS-2, the inhibition curves for 2-AG and 2-AG ether involve a single phase. Figure 7 shows the effect of IBP on AA oxygenation by huPGHS-2. Unlike that seen with 2-AG and 2-AG ether, the best fit curve is biphasic for inhibition of AA oxygenation. IBP causes approximately 50% inhibition through a higher affinity IBP binding event, with an IC50 of about 120 μM. The remainder of the inhibition occurs through a second lower affinity IBP binding event, having an IC50 of about 1 mM (i.e., 948 μM). One simple explanation for these data is that the initial and apparently incomplete phase of inhibition of AA oxygenation reflects partial allosteric inhibition upon IBP occupancy of Eallo, while the second phase represents competitive IBP binding to Ecat. The fact that the IC50 for the first phase is 10–20 times higher than the IC50 for 2-AG ether oxygenation is consistent with the idea that IBP needs to displace AA bound to Eallo to cause the first phase of inhibition.

Fig. 7.

Instantaneous inhibition of huPGHS-2-mediated oxygenation of AA by IBP. The indicated concentrations of ibuprofen were present in a standard O2 electrode assay mixture along with 25 μM AA, and purified huPGHS-2 was added to initiate oxygenation. O2 consumption was monitored as described in the Experimental Procedures. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± SD. Control values for each enzyme variant are normalized to 100%. Significant differences from the control value (with no inhibitor) were seen at all IBP concentrations, as determined by the Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism software. For the biphasic mode shown in this figure, IC50 values were calculated by using nonlinear regression to fit the data to a biphasic dose-response.

DISCUSSION

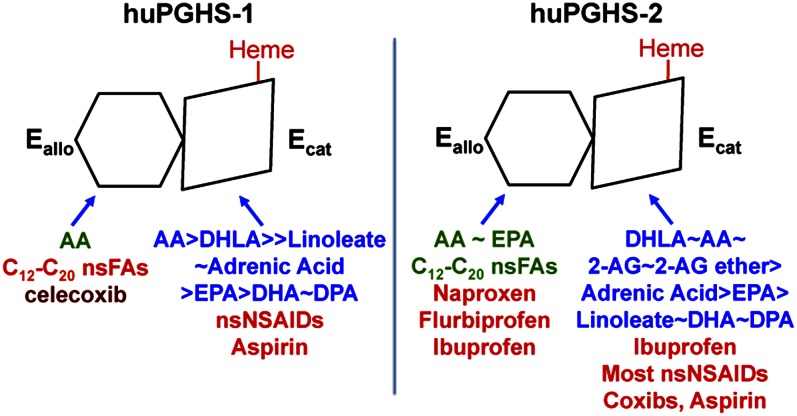

PGHSs function in solution as conformational heterodimers composed of Ecat and Eallo monomers. In previous studies, we have identified the Eallo versus Ecat binding specificities of huPGHSs toward FAs from a number of functional classes and of a variety of NSAIDs (7, 8, 10, 15). Here we have determined the binding specificities of 2-AG ether and ibuprofen toward Eallo and Ecat of PGHS-2. Figure 8 compares the specificities of a number of ligands toward Eallo and Ecat of both PGHS-1 and PGHS-2.

Fig. 8.

Isoform specific interactions of COX substrates, nsFAs, and COX inhibitors with huPGHS-1 and huPGHS-2. Both PGHS isoforms are sequence homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers composed of an allosteric (Eallo) and a catalytic (Ecat) subunit. The individual subunits of huPGHSs differ in their affinities for ligands and in the nature and amplitude of their effects. COX substrates are shown in blue in approximate order of their catalytic efficiencies. Note that FAs that can function as COX substrates can interfere with PGH2 formation by competing with the most common substrate, AA, for the Ecat. Ligands shown in green allosterically stimulate COX activity. Ligands shown in red interfere with COX activity either allosterically by binding Eallo or competitively by binding Ecat. Ligands that bind Eallo can also affect responses to COX inhibitors. For example, nsFAs bound to Eallo of huPGHS-1 increase the rate of aspirin acetylation, whereas celecoxib (in dark red) bound to Eallo of huPGHS-1 may interfere with aspirin action. DHLA, dihomo-γ-linolenic acid; DPA, docosapentaenoic acid; nsNSAIDs, nonspecific NSAIDs.

The 2-AG is a relatively good substrate for muPGHS-2 and huPGHS-2, but a poor substrate for ovine PGHS-1 (15, 18). Ovine PGHS-1 oxygenates 2-AG at 5% of the rate of AA, whereas 2-AG is oxygenated at 65–75% of the rate of AA by PGHS-2; moreover, the Km values for PGHS-2 with AA and 2-AG are similar (15, 18).

Our present studies indicate that huPGHS-2 has essentially the same kinetic properties and forms a homologous set of products with 2-AG and 2-AG ether. These two substrates have indistinguishable Km and Vmax values, are activated to similar extents by common nsFAs, and are inhibited to similar extents and apparently via similar mechanisms by IBP

The 2-AG ether exhibits a preference for binding Ecat versus Eallo. These results are consistent with recent studies by Marnett and coworkers that have indicated that 2-AG binds Ecat with about 10 times higher affinity than Eallo (11). The Km for 2-AG ether, which is equivalent to the Kd for 2-AG ether binding to Ecat, is 5–10 μM (15). The marked preference of 2-AG and 2-AG ether for Ecat of huPGHS-2 is unlike that observed with FA substrates, such as AA and EPA, that bind Eallo with 20–30 times greater affinity than Ecat (7, 15). Presumably neither the ester nor ether groups of 2-AG or 2-AG ether, respectively, effectively interact with Arg-120 of Eallo.

Because 2-AG ether is more stable than 2-AG, which readily hydrolyzes or rearranges (12, 21), 2-AG ether can be used as a stable surrogate for examining 2-AG as a COX substrate. The 2-AG ether is reportedly formed in vivo (22), but its physiologic importance is unclear (23), and it is generally less biologically potent than 2-AG itself (24).

We have previously reported that nsFAs cause about a 2-fold decrease in the Km of PGHS-2 for AA (7, 9); however, the difference the between Km values with and without nsFAs are small and are based on experiments in which it is difficult to estimate the amount of AA versus nsFA bound to Eallo because the AA concentration rapidly decreases during measurements of COX activities. The 2-AG ether, because it appears not to effectively compete with nsFAs for Eallo, is a useful substrate for discriminating between effects on Km versus Vmax. As illustrated in Fig. 3, PA primarily affects the Vmax and not the Km for 2-AG ether. Marnett and coworkers have reported similar results for the effect of another allosteric activator, 13-methyl AA, on 2-AG oxygenation (11). Thus, in contrast to what we had previously hypothesized (7), we now suspect that the effect of nsFAs to stimulate AA oxygenation by huPGHS-2 results primarily from an effect on the Vmax for AA. This is also consistent with naproxen being a negative allosteric regulator of huPGHS-2 by reducing the Vmax without changing the Km for AA (7).

Marnett and coworkers reported that IBP causes a noncompetitive inhibition of 2-AG oxygenation that they attributed to a high affinity binding of one molecule of IBP to muPGHS-2 (13). Additionally, they indicated that IBP is a competitive inhibitor of AA oxygenation by muPGHS-2 and that inhibition of AA oxygenation involves the binding of two IBP molecules per dimer. Our results on the inhibition of 2-AG ether oxygenation by IBP parallel those with 2-AG reported by the Marnett laboratory. Studies with huPGHS-2 variants having Arg120Ala substitutions in Eallo and/or Ecat indicate that IBP can completely inhibit the oxygenation of 2-AG ether by binding either Eallo or Ecat. However, IBP is slightly better able to bind Eallo than Ecat in the presence of 2-AG ether. In contrast to what was reported for muPGHS-2 (13), we find that IBP inhibition of AA oxygenation by huPGHS-2 is a mixed inhibition involving allosteric and competitive components, probably mediated by sequential binding of IBP to Eallo then Ecat. The basis for the species difference in IBP inhibition of AA oxygenation by muPGHS-2 versus huPGHS-1 is unclear. The allosteric inhibitory effect of IBP on AA oxygenation may simply be much more pronounced with huPGHS-2 than with muPGHS-2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Michael Malkowski, David L. DeWitt, Zora Djuric, and Gilad Rimon for carefully reading and commenting on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- 2-AG

- 2-arachidonoylglycerol

- 2-AG ether

- 2-O-arachidonylglycerol ether

- COX

- cyclooxygenase

- Eallo

- allosteric monomer

- Ecat

- catalytic monomer

- hu

- human

- IBP

- (S)-(+)-ibuprofen

- mu

- murine

- ns

- nonsubstrate

- NSAID

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PA

- palmitic acid

- PG

- prostaglandin

- PGHS

- prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase

- RP

- reverse-phase

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants GM68848, CA130810, and HL117798. W.L.S. and R.C.M. have served as consultants for Cayman Chemical Company, products from which were used in this study. The other authors have no conflicts of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schneider C., Pratt D. A., Porter N. A., and Brash A. R.. 2007. Control of oxygenation in lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase catalysis. Chem. Biol. 14: 473–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai A. L., and Kulmacz R. J.. 2010. Prostaglandin H synthase: resolved and unresolved mechanistic issues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 493: 103–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouzer C. A., and Marnett L. J.. 2011. Endocannabinoid oxygenation by cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochromes P450: Cross-talk between the eicosanoid and endocannabinoid signaling pathways. Chem. Rev. 111: 5899–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith W. L., Urade Y., and Jakobsson P. J.. 2011. Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 111: 5821–5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grosser T., Yu Y., and Fitzgerald G. A.. 2010. Emotion recollected in tranquility: Lessons learned from the COX-2 saga. Annu. Rev. Med. 61: 17–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulmacz R. J., and Lands W. E.. 1984. Prostaglandin H synthase. Stoichiometry of heme cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 259: 6358–6363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong L., Vecchio A. J., Sharma N. P., Jurban B. J., Malkowski M. G., and Smith W. L.. 2011. Human cyclooxygenase-2 Is a sequence homodimer that functions as a conformational heterodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 19035–19046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou H., Yuan C., Dong L., Sidhu R. S., Hong Y. H., Kuklev D. V., and Smith W. L.. 2012. Human cyclooxygenase-1 activity and its responses to COX inhibitors are allosterically regulated by nonsubstrate fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 53: 1336–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan C., Sidhu R. S., Kuklev D. V., Kado Y., Wada M., Song I., and Smith W. L.. 2009. Cyclooxygenase allosterism, fatty acid-mediated cross-talk between monomers of cyclooxygenase homodimers. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 10046–10055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong L., Zou H., Yuan C., Hong Y. H., Kuklev D. V., and Smith W. L.. 2016. Different fatty acids compete with arachidonic acid for binding to the allosteric or catalytic subunits of cyclooxygenases to regulate prostanoid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 291: 4069–4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudalkar S. N., Nikas S. P., Kingsley P. J., Xu S., Galligan J. J., Rouzer C. A., Banerjee S., Ji L., Eno M. R., Makriyannis A., et al. . 2015. 13-Methylarachidonic acid is a positive allosteric modulator of endocannabinoid oxygenation by cyclooxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 7897–7909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vecchio A. J., and Malkowski M. G.. 2011. The structural basis of endocannabinoid oxygenation by cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 20736–20745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prusakiewicz J. J., Duggan K. C., Rouzer C. A., and Marnett L. J.. 2009. Differential sensitivity and mechanism of inhibition of COX-2 oxygenation of arachidonic acid and 2-arachidonoylglycerol by ibuprofen and mefenamic acid. Biochemistry. 48: 7353–7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mbonye U. R., Yuan C., Harris C. E., Sidhu R. S., Song I., Arakawa T., and Smith W. L.. 2008. Two distinct pathways for cyclooxygenase-2 protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 8611–8623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong L., Sharma N. P., Jurban B. J., and Smith W. L.. 2013. Pre-existent asymmetry in the human cyclooxygenase-2 sequence homodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 28641–28655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suram S., Gangelhoff T. A., Taylor P. R., Rosas M., Brown G. D., Bonventre J. V., Akira S., Uematsu S., Williams D. L., Murphy R. C., et al. . 2010. Pathways regulating cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and eicosanoid production in macrophages by Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 30676–30685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheelan P., Zirrolli J. A., and Murphy R. C.. 1995. Analysis of hydroxy fatty acids as pentafluorobenzyl ester, trimethylsilyl ether derivatives by electron ionization gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 6: 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozak K. R., Rowlinson S. W., and Marnett L. J.. 2000. Oxygenation of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol, to glyceryl prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 33744–33749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rome L. H., and Lands W. E. M.. 1975. Structural requirements for time-dependent inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis by anti-inflammatory drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 72: 4863–4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blobaum A. L., Xu S., Rowlinson S. W., Duggan K. C., Banerjee S., Kudalkar S. N., Birmingham W. R., Ghebreselasie K., and Marnett L. J.. 2015. Action at a distance: Mutations of peripheral residues transform rapid reversible inhibitors to slow, tight binds of cyclooxyenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 12793–12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savinainen J. R., Jarvinen T., Laine K., and Laitinen J. T.. 2001. Despite substantial degradation, 2-arachidonoylglycerol is a potent full efficacy agonist mediating CB(1) receptor-dependent G-protein activation in rat cerebellar membranes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 134: 664–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanus L., Abu-Lafi S., Fride E., Breuer A., Vogel Z., Shalev D. E., Kustanovich I., and Mechoulam R.. 2001. 2-arachidonyl glyceryl ether, an endogenous agonist of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 3662–3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones E. K., and Kirkham T. C.. 2012. Noladin ether, a putative endocannabinoid, enhances motivation to eat after acute systemic administration in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166: 1815–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiura T., Kodaka T., Nakane S., Miyashita T., Kondo S., Suhara Y., Takayama H., Waku K., Seki C., Baba N., et al. . 1999. Evidence that the cannabinoid CB1 receptor is a 2-arachidonoylglycerol receptor. Structure-activity relationship of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, ether-linked analogues, and related compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 2794–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.