Abstract

Background

The CAIDE (Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia) Dementia Risk Score is a validated tool to predict late-life dementia risk (20 years later), based on midlife vascular risk factors. The goal was to render this prediction tool widely accessible.

Methods

The CAIDE Risk Score (mobile application) App was developed based on the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score, involving information on age, educational level, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and physical inactivity.

Results

The CAIDE Risk Score App is an evidence-based practical tool, which allows users to detect their individual risk, provides guidance for risk modification, and suggests consulting a health care practitioner if needed. Moreover, it allows practitioners to discuss preventive measures and monitor risk reduction.

Conclusions

The CAIDE Risk Score App is the first to predict the risk for dementia through an important evidence-based tool. The App can encourage users to actively decrease their modifiable risk factors and postpone cognitive impairment and dementia.

Keywords: Dementia risk score, Dementia prediction, Dementia prevention, Vascular risk factors, Mobile health, Mobile applications

1. Introduction

It was estimated that 44 million people were living with dementia worldwide in 2013, and the prevalence is predicted to double every 20 years, reaching 76 million in 2030 and 136 million in 2050 [1], [2]. The estimated annual worldwide socioeconomic cost of dementia was US $604 billion in 2010, creating a daunting burden [3]. Considering that there are no available curative treatments for dementia, prevention has recently been highlighted as a major public health priority by the G8 dementia summit and the World Health Organization (WHO) [4], [5].

During the last decade, findings from observational studies have revealed several important midlife vascular and metabolic risk factors that increase the risk for dementia (for a review see [6]). Based on these risk factors, the CAIDE (Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia) Dementia Risk Score was developed to identify individuals at increased risk for dementia, who necessitate preventive interventions to reduce their risk [7]. This risk score is based on multifactorial risk estimation using age, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, physical inactivity, obesity, and educational level as the model parameters. The CAIDE Dementia Risk Score was also externally validated in a multiethnic population in the United States [8]. Of interest, the addition of other midlife risk factors to the CAIDE risk score (central obesity, depressed mood, diabetes mellitus, head trauma, poor lung function, and smoking) did not improve its predictability [8]. Although taking into account the prevalence and co-occurrence of modifiable risk factors, it was estimated that approximately one third of AD cases are attributable to seven risk factors (midlife hypertension, diabetes mellitus, physical inactivity, midlife obesity, depression, smoking, and low education) [9]. A reduction of 10%–20% in these risk factors may reduce AD prevalence by 8%–15% by 2050, which highlights the potential for preventive strategies [9].

Using the original CAIDE Dementia Risk Score, the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER) recruited participants who at baseline had a CAIDE Dementia Risk Score of ≥6 points (indicating the presence of modifiable risk factors) and cognitive performance at the mean level or slightly lower than expected for age. The multimodal intervention consisted of nutritional guidance, exercise, cognitive training, and intensive monitoring of vascular and metabolic risk factors. This study demonstrated that when at-risk participants were subjected to an intensive multimodal lifestyle intervention for 2 years, there was a significant beneficial intervention effect on global cognition score; the score in the intervention group was 25% higher than that in the control group [10]. This is the first demonstration that cognitive functions can be maintained or improved among older adults. Moreover, the risk of cognitive impairment was 31% higher in the control group compared with the intervention group. These findings indicate that the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score is an extremely valuable tool for detecting individuals at high risk for dementia, who are also likely to benefit from lifestyle interventions and proper management of vascular risk factors, given that most of their risk factors for dementia and cognitive decline are modifiable.

Considering the utility of this risk score, the investigators who have developed the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score [7] have sought to make it more accessible to health care practitioners and the general public through the use of mobile health (mHealth) technologies and more precisely through developing a mobile application (App). mHealth Apps can serve various functions such as providing evidence-based information, alert systems, remote consultation/monitoring and diagnostic/treatment support, assessing compliance to medication regiments, and promoting healthy lifestyles (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, sleep) [11], [12]. Some Apps also collect information for databases that can be used for research analyses and improvement of health care systems [13]. As recently highlighted, the most marked potential for mHealth is the prevention of chronic noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), which can significantly alleviate the burden on individuals and health care systems through cost reductions [12]. The WHO and the International Telecommunication Union have recently launched the collaborative mHealth initiative to prevent and treat worldwide and enforce appropriate legislations [14]. Using Apps can encourage individuals to take responsibility for their health and lead healthy lifestyles that prevent various NCDs [13], [15]. Consistent with this rationale, the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score App can play a significant role in decreasing dementia incidence and related costs, while enhancing individuals' control over their lifestyle-related risk factors.

Numerous Apps have been developed for diabetes, depression, cardiovascular diseases, and lifestyle changes [16], [17]. To illustrate, Apps in the health and fitness category range between >11,000 (Google play for Android) and 20,000 (App Store for Apple iOS), whereas Apps for the medical category range between 5000 (Google play) and 14,000 (App Store) [17]. Although many Apps and mHealth technologies have been created to enable older adults to live independently and “age-in-place,” to the best of our knowledge, none have been developed to estimate dementia risk earlier in life.

The goals of the CAIDE Dementia Risk App are to (1) assess the 20-year risk of developing dementia with the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score among users, (2) inform users about the meaning of their risk score through a graphic display of their risk level, (3) provide users with guidance and suggestions for methods to decrease their risk score (e.g., specific recommendations for increasing physical activity), and (4) recommend users to consult with a health care practitioner (if needed) to discuss appropriate lifestyle interventions and management of vascular and metabolic risk factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Summary of methods for the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score

The CAIDE Risk Score App has been developed based on the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score, which includes common and easily available measures. For a more detailed description of the risk score, including analyses and results, see [7]. The CAIDE study recruited participants from four independent population-based random samples that were involved in the North Karelia Project and the Finnish parts of the Monitoring trends and determinants in Cardiovascular disease (MONICA) Project (FINMONICA) study [18]. Local ethics committees had approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent. At the baseline (midlife) and reexamination (late life) assessments, survey methods were compiled and carried out according to international standards and recommendations based on the WHO MONICA project [19]. The surveys consisted of a self-administered questionnaire on medical history, current health behavior, and health status. Data on dementia diagnosis and cognitive status assessments were also based on international standards and recommendations using a three-stage protocol: (1) screening phase: participants who scored ≤24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination were referred for further examinations. (2) clinical phase included neurologic and cardiovascular examinations and detailed neuropsychological testing. (3) differential diagnostic phase involving blood tests, neuroimaging (magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography), cerebrospinal fluid analyses, and an electrocardiogram. According to the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition) [20], dementia and Alzheimer's disease were diagnosed according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association [21].

To simplify the scoring methods, variables included in the risk score were dichotomized using standard cutoffs (sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, current smoking status, and physical activity level) or categorized in tertiles (age and education).

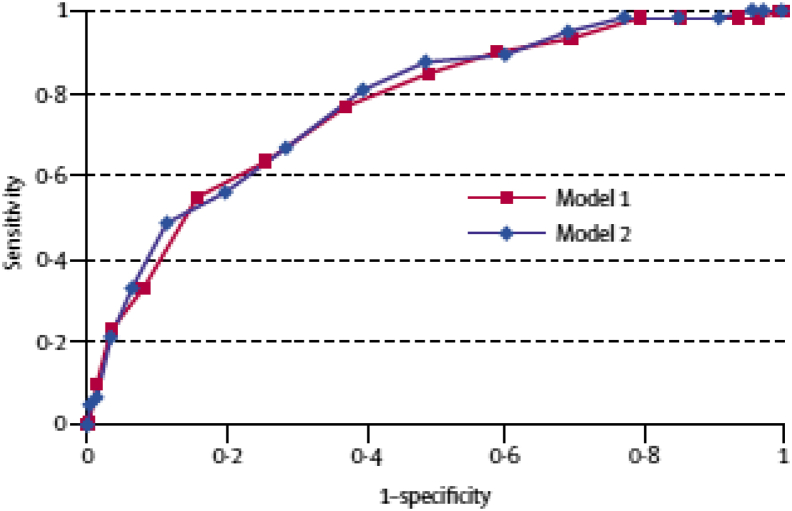

A supplementary risk score was developed including the apolipoprotein ε (APOE) genotype status in the model (APOE ε4 carriers vs. noncarriers). However, considering that inclusion of APOE ε4 was not found to change the predictive value of the model, the App did not include APOE ε4. In summary, the receiver-operating characteristic curves demonstrate that the dementia risk score effectively predicted subsequent dementia. For the basic risk score (model 1), the area under the curve was 0.77 (95% confidence interval: 0.71–0.83; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves showing the performance of the dementia risk scores in predicting the risk of dementia in 20 years among those in middle age. The AUC for model 1 was 0.769 (95% CI: 0.709–0.829). The AUC for model 2 was 0.776 (95% CI: 0.717–0.836). (Figure adapted from [7].) Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

2.2. Methods for the development of the CAIDE Risk Score App

To develop the CAIDE Risk Score App, we established a collaboration with Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH (Germany), which engages in research and development of innovative pharmaceutical and medical products for various medical fields, including neurology and dermatology.

2.2.1. Technical description of the CAIDE Risk Score App

Two versions of the App are available, one for health care personnel and one for the general public, and this selection only needs to be made the first time the App is used. The main difference between the two versions is that a health care provider can enter a profile including his/her name, name and contact details of practice, and Web site.

The App can be downloaded for free from the App Store and may be used on an iPhone or iPad. The App is currently available in five languages: English (as default), German, French, Spanish, and Russian. Additional languages including Swedish and Finnish will be added in the near future. Within a few months of launching the App, >700 users have downloaded it, and this number is continuing to increase across the following regions: Europe, United States and Canada, Asia Pacific, Latin America and Caribbean, Africa, Middle East, and India.

2.2.2. Calculation and visualization of dementia risk

The CAIDE Risk Score App was developed based on the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score described previously, which allows the prediction of the later risk of dementia using the risk profile in midlife (age 40–65 years).

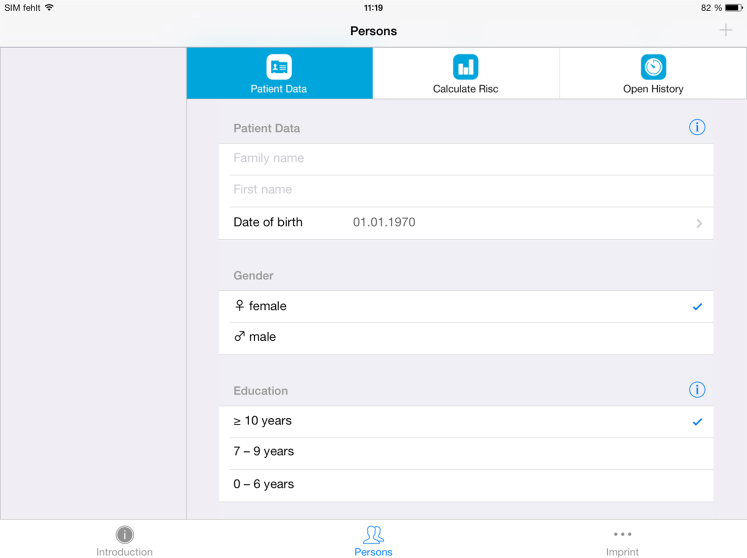

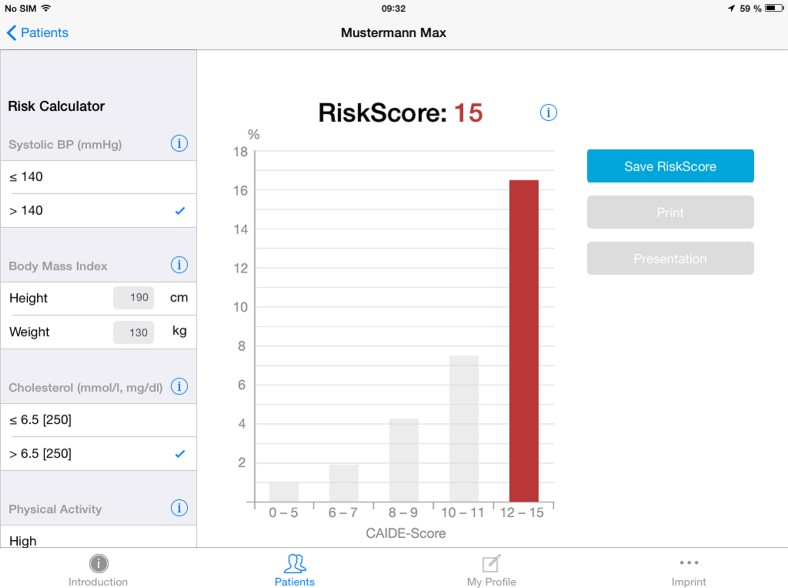

Users—whether lay people who want to calculate their own risk or health care providers who are calculating the risk of their clients—are asked to enter age, sex, date of birth, height and weight, serum cholesterol, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, physical activity status, and years of education (as shown in Fig. 2). The App then calculates the risk score and displays the risk level. For scores in the “normal” range (score of 8–9), an orange bar appears; if the risk is lower than the normal range (score of 0–7), a green bar appears; and if it is higher than average (score of 10–15), a red bar appears (as shown in Fig. 3). In the background information for systolic blood pressure and cholesterol, users are advised to discuss preventive lifestyle interventions with their physician if necessary.

Fig. 2.

CAIDE Risk Score App screenshot displaying the demographic information required for calculation of the risk score. Abbreviations: CAIDE, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia; BP, blood pressure.

Fig. 3.

CAIDE Risk Score App screenshot showing a graphic representation of the risk score. Abbreviations: CAIDE, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia; BP, blood pressure.

Even if the risk scores are clustered in intervals leading to the same probability of developing dementia, the App visualizes small changes of 1 point in risk score within the same cluster by filling the bar more or less with color. This is for motivational reasons so that even a single point of reduction may be seen. Also the green and red colors are differentiated: the lower the risk score the darker the green color and the higher the risk score the darker the red color becomes.

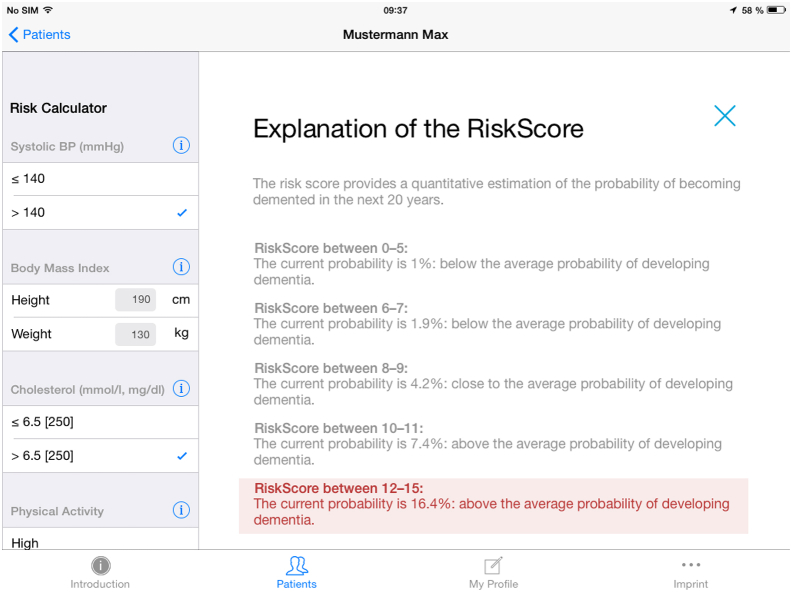

2.2.3. Guidance for risk reduction

The CAIDE Risk Score App provides an explanation of the risk score and provides a probability percentage, comparing it to the average probability of developing dementia (Fig. 4). The App also includes simple information on how the risk factors can be modified. For example, how a short duration of formal education can be compensated by various cognitively stimulating activities and how one can easily increase physical activity in daily life. To reduce systolic blood pressure, it is suggested to exercise; reduce weight, salt intake and levels of psychological stress; and avoid excess alcohol consumption. As background information about serum cholesterol, three bullets points provide examples of food sources rich in unsaturated fatty acids, examples of which sources of animal fat to reduce or increase and encourages the increase of fibers. The App also recommends referring to a physician for more guidance and appropriate treatments if needed (e.g., to decrease high cholesterol levels or blood pressure levels).

Fig. 4.

Explanation of the increased risk score. Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

2.2.4. Data protection and compliance

Any personal information or patient data saved in the CAIDE Risk Score App will only be stored locally on the user's device and cannot be accessed by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH or anybody else. If the App contains personal indentification data, the device should be handled with the same care as any hard copy of a medical record as explained in the Data Protection Disclaimer.

Because the App merely predicts risk and does not make diagnoses or suggest treatments or changes of current medication dosages, it is not classified as a medical device and, therefore, needs no regulatory approval by health authorities [22].

3. Discussion

The CAIDE Risk Score App is the first evidence-based App to estimate future dementia risk in midlife. It is a practical and user friendly App that complies with security and privacy guidelines and is free of charge to all users. The App is intended for use by health practitioners and the general public. It allows users to detect their risk, obtain information on their modifiable risk factors, and receive suggestions on how to modify their risk factors. The App also advises users to consult a health care practitioner if needed. Moreover, it allows practitioners to discuss preventive measures and thereafter monitor whether the individual's dementia risk has decreased based on provided guidance and interventions.

After the use of the CAIDE Dementia Risk App, it is important for users with high risk scores to seek further appropriate interventions, which could include other mHealth tools or validated Apps of high quality that focus on reducing the risk factors involved in the CAIDE risk score. Users would benefit from mHealth tools/Apps developed for increasing physical activity levels, improving nutrition, and managing weight. In fact, usage of such Apps to improve lifestyle is already highly popular and has the potential to significantly reduce the rates of chronic disease and health care costs [13]. The CAIDE Risk Score App is an important tool to identify people who might benefit most from using such Apps and who may not be inclined to use them without knowing about their increased risk for dementia. Similar to more recent “multimodal” dementia prevention trials, the most effective Apps are likely to be those that simultaneously target several dementia risk factors (nutrition, physical activity, weight, and vascular risk factors). Moreover, “multimodal Apps” may decrease the burden of having to use and keep track of several Apps, facilitating usage for lay people and health care providers who are monitoring the progress of dementia risk reduction.

The effectiveness of some Apps may be subjected to undergoing randomized controlled trials (RCTs), especially for those with little or no evidence behind them. However, regarding the CAIDE Risk Score App, physicians and other health professionals do not need to wait for RCT evidence before they can start recommending the App, considering that (1) the CAIDE risk score is evidence-based and has been validated both internally and externally, (2) prevalence of dementia has been and continues to increase at an alarming rate, considering the aging of the population worldwide, (3) scientific evidence strongly indicates that lifestyle-related changes can decrease the risk of cognitive impairment as well as that of other chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease, and (4) there are no risks attached to using the CAIDE Dementia Risk App. So, although there is no RCT evidence for the CAIDE App itself, the evidence for the risk score and preventive lifestyle interventions is compelling, as demonstrated by the FINGER study [10]. As suggested by the Institute for Healthcare Informatics report, although evidence for the effectiveness of Apps is needed, there is no need for a 3- to 4-year RCT that is similar to the process of drug development [13].

Considering the wide range of available Apps, people are increasingly finding it difficult to make informed choices regarding Apps that can be effective and reliable, whereas they tend to rely on other customers' reviews [13]. Similarly, physicians and other health professionals are cautious in recommending Apps if they have little or no information regarding the quality, validation, and effectiveness of a particular App. Physicians also perceive the need to first ensure that legal, privacy, and security requirements/regulations are all met. In contrast to many other Apps, privacy and security are not sources of concern for the CAIDE Risk Score App. Physicians are also weary of prescribing Apps for which people have to pay, as reimbursement may be an issue for various reasons. Not only is the CAIDE Risk Score App based on well-validated scientific evidence, it is free of charge to all users, which will prevent caution in recommending it to the general population, where many would benefit from using it.

A review of mHealth Apps targeting prevalent conditions suggested that the primary motivation for developing Apps is for economic and commercial motives rather than research [16]. Moreover, Apps developed for diabetes illustrate a lack of personalized health education, which is essential and recommended by evidence-based clinical guidelines [23]. There is also a lack of prevention Apps that are based on validated models and theories of behavior change [24]. To bridge such gaps, it will be crucial to establish collaborative initiatives between industries developing Apps and academic research institutes [24]. It will also be important to create and use platforms that allow for data pooling and shared analyses across Apps [25].

Usage of the CAIDE Risk Score App by a wide audience has a promising potential to detect people's individual risk for cognitive decline and motivate them to pay attention to appropriate lifestyle changes. This may decrease the burden on medical and health services through decreasing or postponing the onset of dementia and other NCDs such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, which share the same risk factors included in the CAIDE Dementia Risk Score.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Dementia and Alzheimer's disease have reached epidemic proportions, with heavy economical, social, and medical burdens. Early detection and prevention are highlighted as important public health priorities, and there is a need for widely accessible tools to predict dementia risk.

-

2.

Interpretation: The CAIDE (Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia) Dementia Risk score is a validated tool to predict late-life dementia risk, based on the presence of midlife vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, low education, obesity, and physical inactivity). To make this prediction tool more widely available, a mobile application (App), “The CAIDE Risk Score App” has been developed and is free of charge. It is the first evidence-based App intended for use by patients and health practitioners.

-

3.

Future directions: The use of the App will encourage users to actively decrease their risk factors and has the potential to postpone the onset of dementia, as well as other chronic conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Claudia Werner-Schwarz at Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH for her support throughout the development of the CAIDE Risk Score App and for providing the screenshots from the App, which were included as figures in the article.

The development of the App was funded by Merz Pharmceuticals GmbH. M.K. receives research support from the Academy of Finland, the Swedish Research Council, Alzheimerfonden, American Alzheimer Association, AXA Research Fund, and EU 7th framework large collaborative project grant (HATICE), and the Salama Bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation. S.S. receives postdoctoral funding from the Fonds de la recherche en sante du Quebec (FRSQ). H.S. receives funding from EU 7th framework collaborative project grant (HATICE), Academy of Finland for Joint Program of Neurodegenerative Disorders–prevention (MIND-AD), UEF strategic funding for UEFBRAIN, and EVO/VTR funding from Kuopio University Hospital. J.T. receives funding from the EU 7th framework large collaborative project grant (ePREDICE).

Footnotes

M.K. has served on scientific advisory boards for Pfizer Inc., Elan Corporation, Alzheon, and Nutricia; and received speaker honoraria from Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., and Merz. H.S. has served as a consultant for ACImmune. E.C. and J.F. are employees of Merz Pharmceuticals GmbH.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Disease International. Policy Brief for Heads of Government: The Global Impact of Dementia 2013-2050. London: Alzheimer's Disease International, 2013. Available at: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/GlobalImpactDementia2013.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 2.Brookmeyer R., Johnson E., Ziegler-Graham K., Arrighi H.M. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wimo A., Jonsson L., Bond J., Prince M., Winblad B., Alzheimer Disease International The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:1–11 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.G8 Health Ministers. G8 Dementia Summit declaration. 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/265869/2901668_G8_DementiaSummitDeclaration_acc.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 5.(WHO) WHO . World Health Organization—Alzheimer's Disease International; Geneva: 2012. Dementia: a public health priority. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sindi S., Mangialasche F., Kivipelto M. Advances in the prevention of Alzheimer's disease. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7:50. doi: 10.12703/P7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivipelto M., Ngandu T., Laatikainen T., Winblad B., Soininen H., Tuomilehto J. Risk score for the prediction of dementia risk in 20 years among middle aged people: A longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:735–741. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70537-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Exalto L.G., Quesenberry C.P., Barnes D., Kivipelto M., Biessels G.J., Whitmer R.A. Midlife risk score for the prediction of dementia four decades later. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norton S., Matthews F.E., Barnes D.E., Yaffe K., Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer's disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngandu T., Lehtisalo J., Solomon A., Levalahti E., Ahtiluoto S., Antikainen R. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2255–2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AARP International. Mobile health for independent living : landscape report. Available at: http://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/handle/1/2753. Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 12.Mehregany M., Saldivar E. Opportunities and obstacles in the adoption of mHealth. In: Krohn R., Metcalf D., editors. mHealth: From smartphones to smart systems: Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) 1st ed. 2012. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aitken M. Patient Apps for Improved Healthcare From Novelty to Mainstream. Parsippany, NJ: IMS Institute for Healthcare Infomatics; 2013. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Reports/Patient_Apps/IIHI_Patient_Apps_Report.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 14.Fighting the global health burden through new technology: WHO-ITU joint Program on mHealth for NCDs. World Health Organization 2013. Available at: http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/ICT-Applications/eHEALTH/Be_healthy/Documents/mHealth_for_NCDs_June2013.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 15.Parmar P., Krishnamurthi R., Ikram M.A., Hofman A., Mirza S.S., Varakin Y. The Stroke Riskometer(TM) App: Validation of a data collection tool and stroke risk predictor. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:231–244. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Perez B., de la Torre-Diez I., Lopez-Coronado M. Mobile health applications for the most prevalent conditions by the World Health Organization: Review and analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Perez B., de la Torre-Diez I., Lopez-Coronado M., Herreros-Gonzalez J. Mobile apps in cardiology: Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;1:e15. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puska P. From Framingham to North Karelia: From descriptive epidemiology to public health action. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): A major international collaboration. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association AP . 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKhann G., Drachman D., Folstein M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medical device stand-alone software including apps. Available at: http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/medical-devices-software-applications-apps/medical-device-stand-alone-software-including-apps. Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 23.Chomutare T., Fernandez-Luque L., Arsand E., Hartvigsen G. Features of mobile diabetes applications: Review of the literature and analysis of current applications compared against evidence-based guidelines. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e65. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomlinson M., Rotheram-Borus M.J., Swartz L., Tsai A.C. Scaling up mHealth: Where is the evidence? PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen C., Haddad D., Selsky J., Hoffman J.E., Kravitz R.L., Estrin D.E. Making sense of mobile health data: An open architecture to improve individual- and population-level health. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e112. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]