Abstract

Background

We sought to validate the prognostic significance of Estrogen Receptor alpha (ERα) expression and to investigate the relationship between ESR1 mutation status and outcomes in a large cohort of patients with endometrial cancer. We also investigated the predictive value of ERα for lymph node involvement in a large surgically staged cohort.

Methods

A tumor microarray (TMA) was constructed including only pure endometrioid adenocarcinomas, stained with ER50 monoclonal antibody, and assessed using digital image analysis. For mutation analysis, somatic DNA was extracted and sequenced for ESR1 gene hotspot regions. Differences in patient and tumor characteristics, recurrence and survival between ERα positive and negative, mutated and wild-type tumors were evaluated.

Results

Sixty (18.6%) tumors were negative for ERα. Absence of ERα was significantly associated with stage and grade, but not with disease-free or overall survival. ERα was a strong predictor of lymph node involvement (RR: 2.37, 95% CI: 1.12–5.02). Nineteen of 1034 tumors (1.8%) had an ESR1 hotspot mutation; twelve in hotspot 537Y, four in 538D and three in 536L. Patients with an ESR1 mutation had a significantly lower BMI, but were comparable in age, stage and grade, and progression-free survival.

Conclusion

Patients with ERα negative endometrioid endometrial cancer are more often diagnosed with higher grade and advanced stage disease. Lymph node involvement is more common with lack of ERα expression, and may be able to help triage which patients should undergo lymphadenectomy. Mutations in ESR1 might explain why some low risk women with low BMI develop endometrial cancer.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the 4th most common cancer in women and the 7th most common cause of cancer death in the US [1, 2]. It accounts for twice the number of deaths as cervical cancer and approximately half the number of deaths as ovarian cancer; still endometrial cancer remains an understudied disease [1, 2].

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the cornerstone of endometrial cancer treatment. Further surgical treatment (i.e. need for lymph node dissection) and adjuvant therapy for endometrial cancer continues to be the subject of international debate and ongoing clinical trials. Unlike other tumor types, e.g. breast cancer [3–6], there are currently no predictive and/or prognostic molecular markers used in the routine clinical management of endometrial cancer. Our aim was to identify a biomarker that, if validated, could be easily implemented into clinical care to help identify which patients could benefit from or could be spared adjuvant therapy, or even lymph node dissection, in order to minimize risks associated with potentially unnecessary treatment.

Unopposed estrogen exposure is a well-known major risk factor for endometrial cancer. Recent data has suggested that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα, gene symbol ESR1), which is involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), could be a promising prognostic marker [7–9]. Wik et al. studied several cohorts of endometrial cancer that had a variety of histologic subtypes and different stage tumors. Absence of ERα expression (assessed by immunohistochemistry) was seen in 21% of 239 endometrioid cases and was associated with reduced survival [9]. The reported hazard ratio was 3.5 (95% CI 1.2–3.7, p<.001) when adjusted for age, grade, and stage, suggesting ERα may be a very powerful prognostic marker [9]. However, not all of the patients investigated in the multivariate analysis of endometrioid tumors were surgically staged and thus could have included occult advanced cancers, which confer a worse prognosis, although the true significance of the finding remains to be determined. Wik and colleagues also found that low ERα expression was associated with EMT and PIK3CA alterations, which may have implications for the choice of adjuvant therapy and targeted agents, raising the possibility that ERα expression could be both prognostic and predictive in endometrial cancer [9]. In addition, query of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), demonstrated a strong association between ESR1 mutation status and progression free survival.

Thus, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the prognostic and predictive significance of ERα protein expression using a novel digital image analysis approach, and ESR1 hotspot mutations in a cohort of patients with endometrial cancer who have undergone comprehensive surgical staging. Exploratory analyses were undertaken to investigate the association between ERα and lymph node status.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry

Patient cohort

Approval for this study was obtained from the Cancer Institutional Review Board. Patients treated at The Ohio State University Medical Center between 2007 and 2012 who were diagnosed and treated for endometrial cancer were identified (cohort 1). Only pure endometrioid adenocarcinomas grade 1–3 at any stage were included (other histology or mixed types were excluded). Patients were comprehensively surgically staged with full pelvic and aortic lymph node dissection (unless aortic lymphadenectomy was not deemed safe). Patient records were retrospectively reviewed for clinical and pathologic characteristics, treatment information, and dates of recurrence, death and last follow up. A tumor micro-array (TMA) was constructed by identifying well preserved areas with the highest tumor cellularity on hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides. A single 1 mm core from each patient donor block was mounted into a recipient paraffin block using a custom-made precision instrument (Beecher Instruments, Silver Spring, MD).

ERα expression

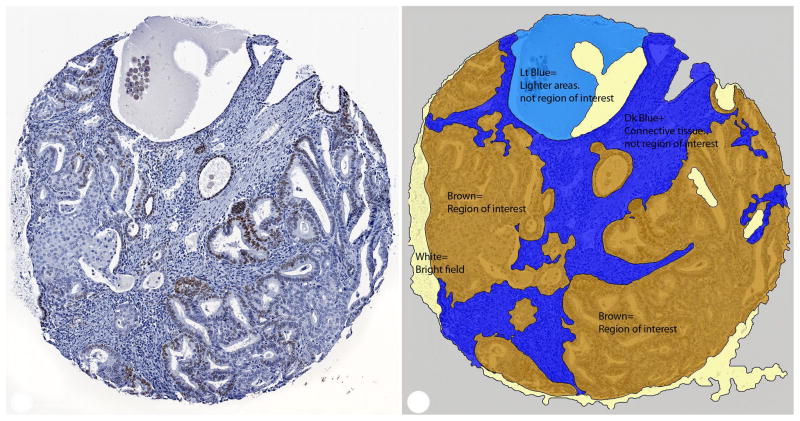

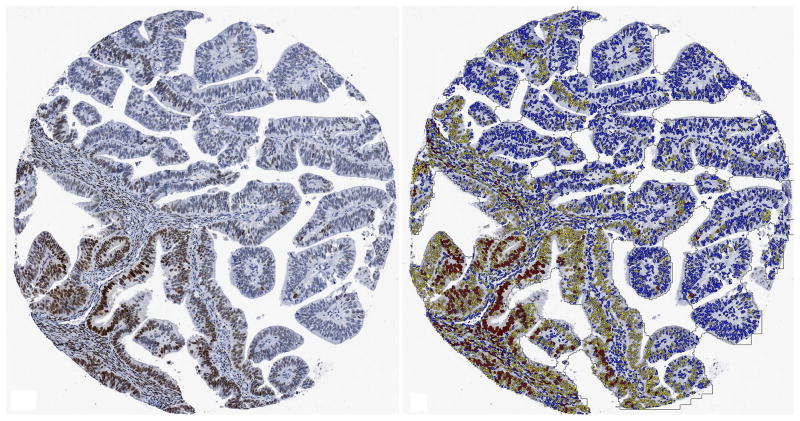

Slides from the TMA were cut at 4 μm. Immunoperoxidase staining was carried out as previously described [10] on the Dako Cytomation Autostainer (Copenhagen, Denmark). For ERα, the ER50 monoclonal antibody (M 7047 at 1:50 dilution) was used. There are no clinical guidelines on fixation of endometrial cancers for IHC; however, formalin fixation times for most of these specimens have been estimated to fall within the 6–72 hours, which has been determined to be ideal for ERα IHC of breast cancer specimens [11]. Digital image analysis [using Tissue Studio 3.5 software (Definiens®, Munich, Germany)] was performed on ERα IHC slides scanned at 20X using ScanScope XT by Aperio (Vista, California). The Tissue Studio 3.5 software uses a context-based, relational analysis of the component pixels in digital slide images to differentiate between types of tissue (adenocarcinoma vs stroma); identify and count IHC-stained nuclei; quantify the intensity and completeness of IHC staining. An algorithm was developed using a dozen selections of ERα-stained nuclei and adjacent tissue (Figure 1). Sections were chosen to give a representative selection of tissue morphologies and stain intensities. An image analysis technician in cooperation with one of the researchers (AAS) designated areas as adenocarcinoma vs stroma. The software then used these designations to recognize similar values in other tissue specimens and assign them to the correct category. Morphologic assignments by the software for each slide were reviewed by the image analysis technician and the researcher (AAS) to confirm their accuracy, and minor adjustments were made as needed. Adenocarcinoma was designated as the region of interest and tissue in this category was subjected to the Detect Nuclei (Positive/Negative) algorithm. Detection parameters were customized to researcher (AAS) specifications. Within the region of interest, the software counted positive and negative-staining nuclei, and counted high and low-staining positive nuclei. Totals and percentages were calculated for each category.

Figure 1. Representative examples of ERα staining.

A. Grade 1 tumor with ER positive and negative nuclei (left) and digital analysis showing regions of interest shaded in brown (right). Stroma (dark blue), and other areas not considered for estimation of tumor positivity (light blue) and “white” (light yellow) were excluded from further analysis. B. Grade 1 tumor showing a spectrum of ER immunoreactivity (left). Digital analysis image with strongly immunoreactive nuclei labeled in red, weakly immunoreactive nuclei labeled in yellow and negative nuclei labeled in blue (right). Non-neoplastic nuclei are also labeled but were excluded from analysis.

ERα expression was recorded as the percentage of stained cells, and classified by dichotomizing IHC expression regardless of intensity as present (≥ 1% staining cells) or absent (<1%) per ASCO/College of American Pathologists Guidelines [12]. To confirm accurate interpretation by digital analysis software cores with <5% ERα expression were reviewed by a pathologist (AAS) and visually scored as ERα- positive or - negative.

ESR1 Mutations

DNA isolation

Formalin fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) archival tissue was obtained from cohort 1 (OSU). An H&E stained section for each case was reviewed by a pathologist and marked to identify regions of tumor. Tissue from three adjacent unstained sections were macro-dissected based on the marked H&E. Somatic DNA was isolated using the MaxWell 16 FFPE Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corp) and quantitated using the Qunat-iT PicoHreen dsDNA assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Cohort 2 included patients treated for endometrioid endometrial cancer at Washington University (St. Louis, MO) between 1991 and 2010. DNA had previously been extracted from flash-frozen tissues [13–16] and cases had been deidentified. Mutation and clinical data for Cohort 3 was obtained using TCGA database [17] selecting for endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

ESR1 mutation screening

We performed amplicon-based sequencing on cohorts 1 and 2. Mutation calls for cohort 3 were obtained from TCGA data matrix. For cohort 1, approximately 10 ng of DNA was used to amplify a 221bp fragment in exon 8 of the ESR1 gene which contained the Y537 and D538 hot spot region. PCR amplification was performed using standard conditions and the Amplitaq Gold Master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following primers; forward -gctcgggttggctctaaagt, reverse-ATGAAGTAGAGCCCGCAGTG. PCR products were directly sequenced using an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer and the BigDyeTerm v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (ThermoFisher). Sequencing files were analyzed using the DNAStar SeqMan Pro software (DNASTAR Inc.). Cohort 2 was amplified using the following primers: forward-GCTCCCATCCTAAAGTGGGTCTTTAA, reverse- TGTGGGAGCCAGGGAGCTCTCAGAC.

Statistical Methods

Patient demographics are summarized via descriptive statistics. Comparisons of these characteristics by ERα status are made via a two-sample t-test for continuous covariates or by chi-squared (or Fisher’s exact) tests for categorical covariates. The influence of ERα as a prognostic marker of survival (recurrence free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS)) was evaluated by the method of Kaplan and Meier, the log rank test and by Cox proportional hazards models[18–20]. Confidence intervals for estimates of survival at a given time point are calculated based on the complimentary log-log transformation of the survival function. Disease free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from surgery to the date of recurrence or death. Patients were censored at their last date known to be recurrence free and alive. Relapse free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from surgery to the date of recurrence. Patients who died before documented recurrence were censored at the time of death. Those who did not die were censored at the date last known to be alive and recurrence free. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time between surgery and the date of death, or the date last known to be alive; disease specific survival (DSS) was defined as the time between surgery and the date of death from disease. Those patients who did not die or who did not die from disease were censored at their last observed date. A priori, based on previous clinical and published information, Cox models were adjusted for age at entry (surgery) and GOG risk category. Exploratory analyses included adjustment for body mass index. Modified Poisson regression models were used to estimate the adjusted relative risk (aRR) between ERα status and positive lymph nodes [21]. All reported p-values and confidence intervals are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple comparisons. Analyses were performed in Stata 13.0 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) and SPSS Statistics (IBM. 1989,2013. IBM SPSS Statistics: Release 22.0.0.0. Armonk, NY).

Results

ERα expression

Tissue cores for 323 endometrioid adenocarcinomas were stained with the ERα antibody and the fraction of positive tumor cells was determined by digital analysis. A representative example of digital analysis is shown in Figure 1A and 1B. One hundred and twenty-two tumors (18.6%) had ERα expression in 1–5% of neoplastic cells. The 122 cases with low percent positivity were visually reviewed (AAS) and 25 cases (20%) reclassified as negative. Non-specific staining artifacts and/or isolated nuclear blush considered as biologically insignificant were the primary findings that resulted in reclassification from low percent ERα positivity to ERα negative status. The rate of ERα positivity ranged from 1%–95% of tumor cells with a mean of 19%. The mean percent positivity was 0.3 for the 60 cases classified as ERα negative.

Absence of ERα (<1% tumor cell positivity) was significantly associated with stage and grade (Table 1). However, a substantially higher proportion of patients with ERα negative tumors had stage II disease or higher (26.7% versus 11.4%, Fisher’s exact test p-value=0.009) and FIGO grade 3 (16.7% versus 6.1%, Fisher’s exact test p-value=0.031). ERα expression was also associated with lymph node metastasis. Twenty-six of 290 (9%) patients with lymphadenectomy were diagnosed with positive lymph nodes. ERα-negative tumors were more likely to have lymph node metastasis than ERα-positive tumors. Thirty-five percent (n=9 of 26) of patients with positive lymph nodes were ERα negative versus 17% (n=44 of 264) of patients who had negative nodes (Fisher’s exact test: p=0.033). Estrogen receptor alpha status was a strong predictor of lymph node involvement (unadjusted RR: 2.37, 95% CI: 1.12–5.02); aRR: 2.25, 95% CI: 1.04–4.89, adjusted for age and BMI). There were no significant differences in age at diagnosis, BMI, or in the proportion of patients who received adjuvant therapy for the ERα positive and -negative patients.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics by estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) expression in endometrioid endometrial cancer.

| Clinicopathologic featurea | ERα negative n=60 (18.6%) |

ERα positive n=263 (81.4%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 59.7 (9.2) | 61.4 (11.0) |

|

| ||

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean, SD) | 39.7 (10.8) | 36.7 (10.2) |

| < 30 | 15 (25.0) | 74 (28.1) |

| 30 – 40 | 13 (21.7) | 92 (35.0) |

| > 40 | 30 (50.0) | 86 (32.7) |

|

| ||

| Grade b | ||

| 1 | 35 (58.3) | 181 (68.8) |

| 2 | 15 (25.0) | 66 (25.1) |

| 3 | 10 (16.7) | 16 (6.1) |

|

| ||

| FIGO Stage b | ||

| I | 44 (73.3) | 233 (88.6) |

| II | 4 (6.7) | 5 (1.9) |

| III | 12 (20.0) | 21 (8.0) |

| IV | 0 | 4 (1.5) |

|

| ||

| Positive nodes | ||

| No | 44 (73.3) | 220 (83.7) |

| Yes | 9 (15.0) | 17 (6.5) |

|

| ||

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| No | 43 (71.7) | 208 (79.1) |

| Yes | 17 (28.3) | 55 (20.9) |

Missing/uninformative cases are as follows: BMI: 2 ERα negative and 11 ERα positive; lymph node positivity: 7 ERα negative and 26 ERα positive

P-value <0.05. Compared via a two sample t-test, assuming unequal variances, for continuous covariates or by Fisher’s exact test for categorical covariates.

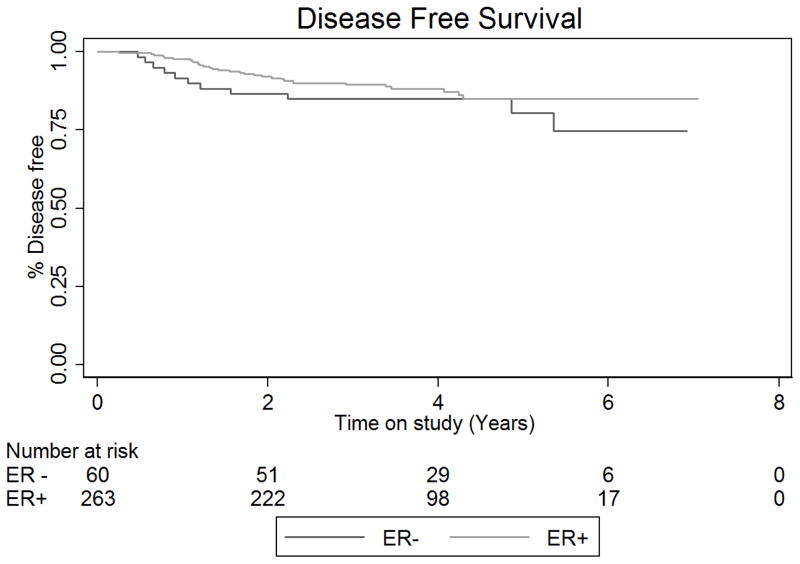

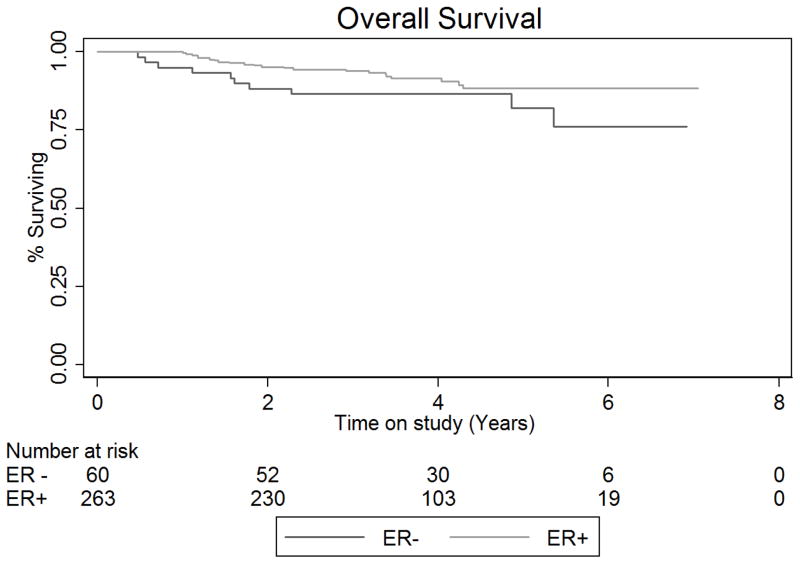

Six (10%) patients with ERα positive tumors and 18 (6.8%) with ERα negative tumors developed recurrent disease. There was no difference in disease free (DFS) or overall survival (OS) for women with ERα positive and ERα negative tumors (Figure 2). The disease free survival rate at 5 years in the ERα negative group was 80.5% (95% CI: 0.65–0.90) and 85.1% (95% CI: 0.79–0.90) in the ERα positive group (Unadjusted Cox HR: 1.48, 95% CI: 0.74–2.94, log rank-test p-value=0.268) The 5-year OS rate (death from any cause) in the ERα negative group was 82.1% (95% CI: 66.2–91.0) and 88.4% (95% CI: 82.2–92.5) in the ERα positive group (Unadjusted Cox HR: 1.83, 95% CI: 0.86–3.87, p-value=0.114). Five-year disease specific survival for those with ERα negative tumors was 91.2% (95% CI: 80.2–96.3) versus 96.2% (95%CI: 91.8–98.3) for patients with ERα positive tumors (Unadjusted HR: 3.0, 95% CI: 0.94–9.39, p-value=0.063). Estimation of adjusted disease specific risk of death was not attempted due to the few number of disease-attributable deaths observed during follow up. None of the multivariable Cox models (for DFS, relapse free survival or OS) indicated violation of the proportional hazards assumption.

Figure 2. Outcomes for endometrial cancer patients stratified by tumor ERα expression.

A. Kaplan-Meier plot for disease-free and B. overall survival. Disease-free survival defined as the time from surgery to the date of recurrence or death. Patients were censored at their last date known to be recurrence free and alive. Overall survival was defined as the time between surgery and the date of death, or the date last known to be alive. Abbreviations: ER +: Estrogen receptor expression positive; ER −: Estrogen receptor expression negative.

ESR1 mutations

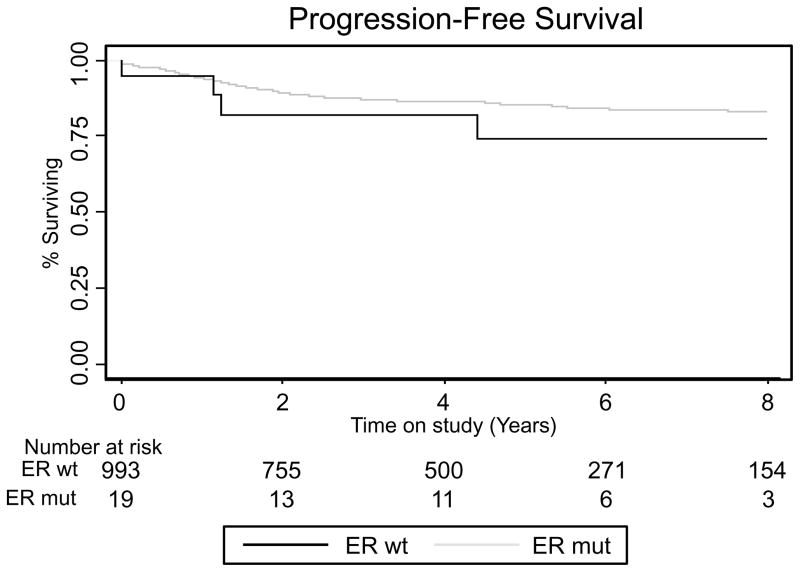

One thousand thirty-four samples were available for mutation analysis. Nineteen (1.8%) patients had a mutation in an ESR1 hotspot, and mutation frequencies were similar among the three cohorts (1.06%, 2.18% and 2.00%, respectively). Twelve mutations that altered amino acid Y537 were found (five Y537N, five Y537S, one Y537C and one Y537Q), four that altered D538 (three D538G and one D538N) and three that altered L536 (L536H and L536P). Patients with an ESR1 mutation had significantly lower BMIs (P=0.001), but were comparable in age, the use of adjuvant therapy, lymph node positivity, stage and grade (Table 2). Four (21%) patients with a mutation developed recurrent/progressive disease compared to 138 (14%) of patients without a mutation (P=0.27). There was no difference in recurrence/progression free survival between mutated and non-mutated patients (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic characteristics by somatic ESR1 hotspot mutation in endometrioid endometrial cancer.

| Clinicopathologic featurea |

ESR1 hotspot mutated n = 19 (1.8%) |

ESR1 hotspot wild-type n = 1015 (98.2 %) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 67.0 (11.3) | 62.7 (11.3) |

|

| ||

| BMI b, kg/m2 (mean, SD) | 28.3 (10.2) | 35.4 (10.1) |

| <30 | 13 (68.4%) | 318 (31.3%) |

| 30–40 | 2 (10.5%) | 345 (34.0%) |

| >40 | 2 (10.5%) | 274 (27.0%) |

|

| ||

| Grade | ||

| 1 | 11 (57.9%) | 521 (51.3%) |

| 2 | 5 (26.3%) | 334 (32.9%) |

| 3 | 3 (15.8%) | 160 (15.8%) |

|

| ||

| FIGO Stage | ||

| I | 15 (78.9%) | 809 (79.7%) |

| II | 1 (5.3%) | 38 (3.7%) |

| III | 2 (10.5%) | 125 (12.3%) |

| IV | 1 (5.3%) | 37 (3.7%) |

|

| ||

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| No | 11 (57.89%) | 585 (57.64%) |

| Yes | 4 (21.05%) | 233 (22.96) |

Missing/uninformative cases are as follows: BMI: 2 mutated and 78 wild-type; lymph node positivity: 3 mutated and 166 wild-type; adjuvant therapy usage: 4 mutated and 197 wild-type; FIGO stage: 6 wild-type.

P-value <0.05. P-values for associations with BMI, grade, and stage calculated using chi-squared (or Fisher’s exact) tests. ¬P-value for age calculated using unpaired t-test.

Figure 3. Outcomes for endometrial cancer patients stratified by tumor ESR1 hotspot mutation.

Kaplan-Meier plot for progression-free survival, defined as the time from surgery to the date of recurrence or progression. Patients were censored at their last date known to be progression/recurrence free and alive. Abbreviations: ER wt: Estrogen receptor wild type; ER mut: Estrogen receptor mutated

Discussion

We set out to identify and validate a potentially quick-to-implement clinical biomarker in endometrioid endometrial cancer. We confirmed that absence of estrogen receptor alpha expression by immunohistochemistry and digital analysis confers an increased risk of advanced stage and higher grade. However, we were unable to confirm a strong prognostic value of ERα expression for recurrence-free or disease-specific survival. Lack of ERα expression did strongly predict lymph node involvement. Furthermore, ESR1 mutations were more common in patients with low BMI.

To our knowledge this study was the first to use digital image analysis to study ERα expression on a large endometrial cancer TMA. Tumor microarrays have been widely applied for discovery of protein expression, however, scoring of TMAs can be time consuming and subjective to inter-interpreter variation. Although digital analysis still requires training by an expert observer/pathologist, once set up and confirmed, digital analysis provides fast and reliable interpretation of digital slides. Similar to high throughput sequencing, digital image analysis can be used for biomarker discovery. If positive findings are noted, immunohistochemistry is easy and fast to implement in clinical practice and relatively inexpensive. There are limitations to digital analysis. We found that in the low ranges (ERα expression < 5%) digital image analysis required manual confirmation and in 20% of these cases the digital analysis scoring (positive versus negative) was changed. Differences between manual and digital analysis in this low range may be due to the small cores on a TMA. Some cores may include smaller amounts of carcinoma and/or have insufficient material for IHC staining. Both may alter computerized interpretation. If clinical decisions are made based on ERα expression we recommend manual confirmation of the cores with < 5% expression.

In contrast to the study by Wik et al. we did not find an increased risk of recurrence/relapse or decreased survival with lack of estrogen receptor alpha expression, nor when adjusted for GOG risk category [9]. Differences in the number of patients who underwent comprehensive surgical staging may have contributed since lack of or incomplete staging may lead to inaccurate stage assignment. As a consequence, this may result in different treatment recommendations, and possible differences in outcomes and prognoses. Complete surgical staging allows us to offer adjuvant treatment to all patients with advanced disease and this may have negated a survival difference between ERα positive and negative cases. Since lack of ERα expression is associated with higher stage, ERα status might be of value in unstaged patients, especially those with other adverse risk factors, to help guide need for adjuvant therapy.

Recent work from two groups has shown that the same ligand binding domain (LBD) hotspot mutations seen in endometrial cancers are associated with acquired hormone resistance in breast cancer [22, 23]. Functional studies revealed that the ESR1 mutations in the LBD are activating, and drive transcription and cell proliferation in the absence of estrogen. Mutations outside of the LBD have been reported by TCGA in endometrioid endometrial cancers, but because these mutations are not predicted to alter protein function and occur in highly mutated tumors, our study focused on the clinical relevance of the hotspot LBD mutations. In the breast cancer studies, the ESR1 hotspot mutations were identified in recurrent/progressive breast cancer and were not present in the primary tumors. The authors speculated that mutations may develop during a low estrogen state (anti-estrogen therapy). Interestingly, most endometrial cancers occur in the setting of prolonged unopposed estrogen exposure, such as in morbid obesity where conversion of androgens to estrogens in the adipose tissues leads to higher estrogen exposure. Mutations in the ESR1 hotspot (in the primary tumor) might explain why normal weight (BMI<30) women without any other risk factors may also develop endometrial cancer.

Lastly, we showed that estrogen receptor alpha status was a strong predictor of lymph node involvement. Although surgical staging is valuable in determining which patients benefit from and which patients may be spared adjuvant therapy, lymphadenectomy is associated with increased morbidity. Prospective trials have failed to demonstrate superior overall survival with routine lymph node dissection [24, 25]. More recently there has been a trend towards selective lymphadenectomy. The most commonly used algorithm was developed and validated by the Mayo Clinic [26]. However, this algorithm is dependent on intraoperative frozen section analysis. Most institutions cannot rely on frozen sections due to false negative diagnoses and inaccurate results for tumor size, grade and myometrial invasion [27–30]. Others are investigating the feasibility and reliability of sentinel lymph node assessment [31]. Preoperative assessment of molecular markers such as ERα expression to predict the risk of lymph node involvement, in addition to intraoperative findings, may allow for a more personalized surgical approach. This is currently being tested in a prospective fashion.

Certainly there are some limitations to our study. First, the better than expected survival and low recurrence rate limits the event rate and power to detect differences. The retrospective nature of the study and need for available tissue allows for inclusion bias. Although the cohort has a relatively long follow up time, clinical data are gathered from patient clinical and outside records, and patients who were lost to follow up may have developed recurrence or died of disease unknowingly. Secondly, the use of a tumor microarray, particularly with a single core per tumor, carries the risk of increased false negatives due to technical issues such as tissue fixation [32] as well as tumor heterogeneity[33, 34]. The use of single cores may have resulted in an increased number of ERα false negative cases, however, Supernat and colleagues demonstrated that ER tumor heterogeneity was significantly lower in endometrioid adenocarcinomas (as the histologic type included in our study). The size and impact of such effect is difficult to estimate but statistically significant associations between lack of ERα expression and poor prognostic factors argue for a minimal impact in this dataset. Lastly, different methods for ER staining (e.g. H-value or H-score) are available, have been described in other studies, and may contribute to different findings between studies. Given a lack of guidelines for ER staining in endometrial cancer, and in order to have a validated biomarker that would be easy to implement in clinical practice, we decided to use the ASCO/College of American Pathologists Guidelines for ER staining (as used in breast cancer) for the current study.

In conclusion, patients with estrogen receptor alpha negative endometrioid endometrial cancer are more often diagnosed with higher grade and advanced stage disease. In addition, mutations in ESR1 might explain why some low risk women with low BMI (in the absence of unopposed estrogen exposure) develop endometrial cancer. Lymph node involvement is more common in patients with lack of ERα expression. Therefore, ERα expression status evaluated on the preoperative endometrial biopsy of curettage, in addition to intraoperative findings, may be able to triage which patients should undergo a lymphadenectomy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by Grant # IRG-67-003-50 from the American Cancer Society (PI: Backes). Christopher Walker is supported by the “Pelotonia Fellowship Program”.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: Dr. Backes has a research grant from Eisai Inc (not related to this manuscript); none of the other authors have a conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivotto IA, Bajdik CD, Ravdin PM, Speers CH, Coldman AJ, Norris BD, et al. Population-based validation of the prognostic model ADJUVANT! for early breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:2716–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, Kim C, Baker J, Kim W, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:3726–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van ‘t Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–6. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albain KS, Barlow WE, Shak S, Hortobagyi GN, Livingston RB, Yeh IT, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in postmenopausal women with node-positive, oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer on chemotherapy: a retrospective analysis of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70314-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jongen V, Briet J, de Jong R, ten Hoor K, Boezen M, van der Zee A, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta and progesterone receptor-A and -B in a large cohort of patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2009;112:537–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelsen IB, Stefansson IM, Akslen LA, Salvesen HB. GATA3 expression in estrogen receptor alpha-negative endometrial carcinomas identifies aggressive tumors with high proliferation and poor patient survival. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;199:543e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wik E, Raeder MB, Krakstad C, Trovik J, Birkeland E, Hoivik EA, et al. Lack of estrogen receptor-alpha is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and PI3K alterations in endometrial carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:1094–105. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backes FJ, Leon ME, Ivanov I, Suarez A, Frankel WL, Hampel H, et al. Prospective evaluation of DNA mismatch repair protein expression in primary endometrial cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2009;114:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gown AM. Current issues in ER and HER2 testing by IHC in breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(Suppl 2):S8–S15. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:2784–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billingsley CC, Cohn DE, Mutch DG, Stephens JA, Suarez AA, Goodfellow PJ. Polymerase varepsilon (POLE) mutations in endometrial cancer: clinical outcomes and implications for Lynch syndrome testing. Cancer. 2015;121:386–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zighelboim I, Goodfellow PJ, Gao F, Gibb RK, Powell MA, Rader JS, et al. Microsatellite instability and epigenetic inactivation of MLH1 and outcome of patients with endometrial carcinomas of the endometrioid type. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2042–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zighelboim I, Mutch DG, Knapp A, Ding L, Xie M, Cohn DE, et al. High frequency strand slippage mutations in CTCF in MSI-positive endometrial cancers. Human mutation. 2014;35:63–5. doi: 10.1002/humu.22463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker CJ, Miranda MA, O’Hern MJ, McElroy JP, Coombes KR, Bundschuh R, et al. Patterns of CTCF and ZFHX3 Mutation and Associated Outcomes in Endometrial Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Pilot Project. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;B34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Amer Statist Assn. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant procedures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;A135:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1446–51. doi: 10.1038/ng.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, Green B, Sakr RA, Will M, et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1439–45. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, Alberto Lissoni A, Signorelli M, Scambia G, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:1707–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373:125–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowdy SC, Borah BJ, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Weaver AL, McGree ME, Haas LR, et al. Prospective assessment of survival, morbidity, and cost associated with lymphadenectomy in low-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2012;127:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Case AS, Rocconi RP, Straughn JM, Jr, Conner M, Novak L, Wang W, et al. A prospective blinded evaluation of the accuracy of frozen section for the surgical management of endometrial cancer. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;108:1375–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245444.14015.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frumovitz M, Slomovitz BM, Singh DK, Broaddus RR, Abrams J, Sun CC, et al. Frozen section analyses as predictors of lymphatic spread in patients with early-stage uterine cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:388–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S, Bandyopadhyay S, Semaan A, Shah JP, Mahdi H, Morris R, et al. The role of frozen section in surgical staging of low risk endometrial cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papadia A, Azioni G, Brusaca B, Fulcheri E, Nishida K, Menoni S, et al. Frozen section underestimates the need for surgical staging in endometrial cancer patients. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2009;19:1570–3. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181bff64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holloway RW, Bravo RA, Rakowski JA, James JA, Jeppson CN, Ingersoll SB, et al. Detection of sentinel lymph nodes in patients with endometrial cancer undergoing robotic-assisted staging: a comparison of colorimetric and fluorescence imaging. Gynecologic oncology. 2012;126:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Permuth-Wey J, Boulware D, Valkov N, Livingston S, Nicosia S, Lee JH, et al. Sampling strategies for tissue microarrays to evaluate biomarkers in ovarian cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2009;18:28–34. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berlth F, Monig SP, Schlosser HA, Maus M, Baltin CT, Urbanski A, et al. Validation of 2-mm tissue microarray technology in gastric cancer. Agreement of 2-mm TMAs and full sections for Glut-1 and Hif-1 alpha. Anticancer research. 2014;34:3313–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Supernat A, Lapinska-Szumczyk S, Majewska H, Gulczynski J, Biernat W, Wydra D, et al. Tumor heterogeneity at protein level as an independent prognostic factor in endometrial cancer. Translational oncology. 2014;7:613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]