Traditional animal models have had limited success mimicking mental illnesses. Emerging technologies offer the potential for a major model upgrade.

Starting with just a tiny chunk of skin, neuroscientist Flora Vaccarino tries to unlock mysteries hidden inside the brains of people with autism. By introducing certain genes to the skin cells, the Yale University School of Medicine researcher reprograms them to an embryo-like state, turning them into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs); and with two more months of nurturing and tinkering, Vaccarino can guide the cells to develop into small balls of neural tissue akin to miniature human brains.

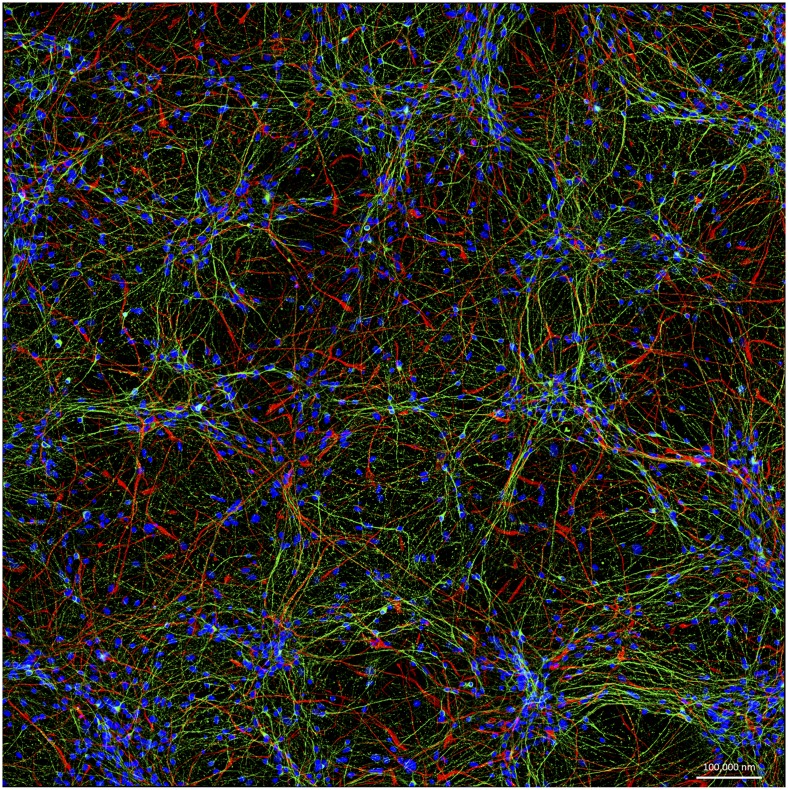

Neurons such as these, derived from the induced pluripotent stem cells of a Parkinson's disease patient, are on the forefront of efforts to improve models for brain disease. Image courtesy of Cedric Bardy and Fred H. Gage (The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA).

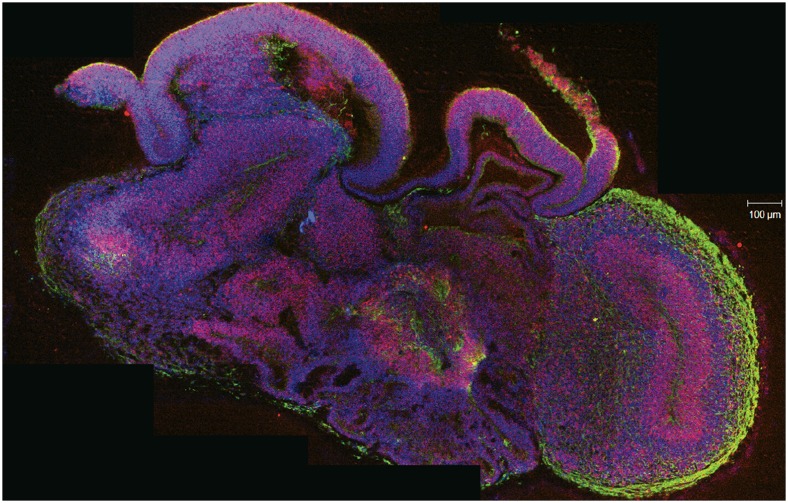

Less than two millimeters across, these “cerebral organoids” don’t look or work exactly like full brains. But they contain many of the same cell types and undergo some of the same key developmental processes as fetal brains. Also key, the cells perfectly match the genetic makeup of the adults and children with autism who donated the original skin samples, allowing Vaccarino’s team to track the very beginnings of their disorder.

Human brain tissue usually can’t be collected and studied until after death, and by then, it can be too late to glean important insights. “You don’t get to see the same person’s cells progressing through a series of steps and time points, like we do with these organoids,” Vaccarino explains. “The organoids are a very powerful system. You can actually change things and see what the outcome is going to be.”

Predicting outcomes and, crucially, developing psychiatric drugs has proven exceedingly difficult in recent decades. Inadequate animal models have been a major stumbling block, researchers say. First developed in 2013 (1), cerebral organoids grown from human iPSCs—affectionately called minibrains by some—are one of several emerging technologies that are finally allowing researchers to make more sophisticated models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Advances in genomics are also helping to shed new light on mental illnesses by pointing researchers to new gene targets. These, in turn, can be combined with recent precision gene-editing techniques to make animal models that many researchers hope will more faithfully reproduce aspects of human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, autism, and schizophrenia.

“It’s a very exciting time,” says Guoping Feng, a neuroscientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Between the technology development and the genetic findings, this is the first time that we’ve been able to begin digging deep into the causes and neurobiology of these disorders.”

The Mouse Problem

For decades, traditional animal models—commonly, genetically engineered mice—have allowed scientists to manipulate the brain’s cells, genes, and molecules, revealing some basic but important insights. Modified mice, for example, have helped reveal how misfolded versions of the α-synuclein protein gunk up the Parkinson’s-diseased brain and possibly injure neurons. Mice with mutations linked to Alzheimer’s disease have helped scientists examine how misfolded amyloid-β protein collects into sticky plaques in the brain.

But most current mouse models simply can’t capture the genetic, cellular, or behavioral complexity of human psychiatric conditions, researchers argue. In many cases, researchers have struggled to clarify the genes and mutations required to replicate brain disorders in mice. In others, scientists have been hampered by fundamental differences between mice and humans in brain structure and function.

Without knowing precisely which molecular or genetic defects to copy, researchers have tried to make animal models that at least mimic human psychiatric symptoms. In one common test for depression-like behaviors, for example, they measure how long mice struggle against being held upside down by the tail. (Animals that give up sooner are typically judged as showing greater “despair.”) But such strategies have met with increasing skepticism, especially in light of the lack of therapeutic breakthroughs.

“We can make models by challenging mice in different ways and looking at their behavior, but it’s not at all clear that these animals have the same disease that we do,” says Fred H. Gage, a neuroscientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

Feng echoed these concerns in a 2015 commentary (2) in Nature Medicine, criticizing the overinterpretation of many current mouse models of brain disorders, in particular those based primarily on matching behavioral signs rather than known or suspected mechanisms. Among his caveats: mice lack a well-developed prefrontal cortex, an area that in humans is thought to mediate higher cognitive functions and appears to play a role in disorders such as autism and schizophrenia.

“I'm not saying mice are not useful for schizophrenia studies, but it’s important to understand the limitations,” says Feng. Instead of relying on hard-to-interpret mouse behaviors, Feng and others have argued in favor of modeling disease-related changes in basic neuronal properties. For example, aberrant electrical properties or abnormal numbers of cell-to-cell connections (synapses) are thought to be involved in several psychiatric disorders, and synapse formation and function appear very similar between mice and humans. “There’s no such thing as schizophrenic behavior in mice, but if I can prove a particular gene causes the same synaptic defect in humans and in mice, and I can correct it in my model, then that has hope as a treatment,” says Feng.

To study brain disorders in living human tissue, researchers grew this cerebral organoid from stem cells derived from a healthy donor's skin sample. In this cross-section, the neurons are green, progenitors are red, and nuclei are blue. Image courtesy of Madeline A. Lancaster and Juergen A. Knoblich. Reproduced from ref. 1, with permission from Macmillan Publishers: Nature, copyright (2013).

Creating Better Copies

Even with greater focus on basic biological mechanisms, researchers must know which genes and mutations to incorporate into models. This alone has proven challenging. But large-scale genomic studies of humans, facilitated by cheap DNA sequencing, are beginning to reveal new candidates, including some for schizophrenia, a disease whose genetic contributors have long perplexed scientists.

No single genetic abnormality accounts for a large number of cases of the disease. Instead, researchers have found many potential hits across different people, each with a relatively small effect on schizophrenia risk, says Pamela Sklar, chief of the psychiatric genomics division at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. “The sample sizes are only now just getting large enough in schizophrenia to be able to do some fine mapping and localizing of genetic risk factors,” says Sklar.

In 2014, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, an international research collaboration, announced their genome-wide scans of more than 150,000 people had found 108 regions associated with risk for schizophrenia (3). And within the chromosomal region with the strongest links to schizophrenia risk identified so far, a team led by researchers at Harvard Medical School reported in January that they had pinpointed a gene that could be a major contributor to the signal coming from this area (4). The C4 (complement component 4) gene encodes a set of immune system proteins, and the team found that the more people expressed one particular form of C4 protein, the greater their risk of developing schizophrenia. In the neurons of newborn mice, researchers found that C4 expression ramped up during the period when cell-to-cell connections normally get pruned and refined. When the researchers made mice with a disabled C4 gene, they saw decreased pruning, leading them to speculate that overproduction of C4 could lead to early hyperactive pruning in people with schizophrenia.

Beyond finding new genes to tweak, identifying the precise mutations in those genes that affect people, and replicating them in mice will be equally important, says Feng. Many past studies have used “knockout” mice, which are designed to fully disable one or both copies of the gene of interest, to understand a gene’s effect. But in reality, human patients often exhibit more subtle mutations that alter gene function rather than eliminate it entirely. “If you don’t make the precise human mutation, you might be studying the wrong disorder,” says Feng.

Feng has been investigating how different mutations in the Shank3 gene contribute to certain forms of either schizophrenia or autism. In a paper published in January, Feng’s group created two lines of mice, each carrying a human mutation associated with one of the conditions (5). Although the models showed some neural deficits in common, mice with an autism-associated mutation developed problems earlier in life, including weakened neuronal signaling in the striatum, which is involved in certain repetitive or compulsive behaviors. Mice with a schizophrenia-associated mutation, on the other hand, showed defects later on, such as reduced signaling in the medial prefrontal cortex, a brain area related to social interactions and decision-making.

Although single genes like Shank3 offer scientists toeholds for studying certain aspects of autism and schizophrenia, generating mouse models with multiple mutations to more closely match human patients has been a significant challenge. With traditional genetic engineering, producing just a few mice with a single desired mutation requires making many generations of animals; adding more mutations multiplies the difficulty.

But new precision gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9 (6), are helping scientists to introduce mutations—even several at a time—directly into eggs or early embryos, to make genetically altered animals in a single generation [see “Core Concept: CRISPR gene editing” (7)]. Researchers are still working to boost efficiency and reduce unintended mutations with the emerging techniques. Even so, they are already much quicker and cheaper than old methods. Moreover, the advent of precision gene editing has made primate models with custom mutations feasible for the first time.

Coming Closer To Humans

Although genetically modified monkeys are still in early development, primate models are advancing quickly. Researchers in China reported the first monkeys created with custom mutations in 2014: a proof-of-principle in cynomolgus monkeys (a type of macaque) possessing mutations in both an immune function gene and a metabolic regulatory gene (8). Other genetically engineered monkeys are in the works, and marmosets have attracted particular interest for studying disorders that disrupt social behavior, such as autism.

“One of the major advantages of monkeys is that their brains are closer to humans in structure and function, compared to mice,” says Feng. “They have a very well-developed prefrontal cortex, and have some higher cognitive functions that we cannot study in mice.”

“Studying social behavior in mice is very artificial,” says Hideyuki Okano, a stem-cell biologist at Keio University in Tokyo. “The marmoset has lots of human-like traits that are missing from the mouse and even the macaque, such as a family structure.” Marmosets typically live in units consisting of two parents and their offspring, and like humans, they also use eye contact to communicate rather than to convey aggression. From a practical perspective, they also cost less than macaques to maintain because of their smaller size and the fact that entire families live together in a single cage (9).

In February, scientists published the first behavioral descriptions of marmosets engineered to overexpress the methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) gene (10); people with mutations in MeCP2 or extra gene copies develop syndromes that include autism symptoms. The marmosets with extra copies of MeCP2 paced obsessively in circles, showed decreased interest in socializing with other marmosets, and produced noises associated with anxiety. The monkeys do not mimic all symptoms seen in humans with additional MeCP2 copies, such as seizures, but the authors propose that the animals could be useful models for studying human brain disorders.

Okano and geneticist Erika Sasaki at Keio University are currently studying genetically engineered marmosets they created to model Rett syndrome, an autism-related disorder. The team has also developed marmoset models of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, and other conditions. At MIT, researchers, including Feng, are preparing to make genetically modified marmosets to study brain disorders as well.

Models are still models, and humans are the only perfect models for humans.

—Guoping Feng

Despite recent excitement about genetically engineered primates, they are unlikely to overtake mice as the dominant model for neuropsychiatric research. Ethical considerations curb their use, and monkeys still take more resources, years instead of months to raise, and produce fewer offspring than mice.

Scientific limitations exist as well. “Models are still models, and humans are the only perfect models for humans,” says Feng. “We still have the same caveat that we cannot diagnose [monkeys], just as we can't diagnose a mouse, with a psychiatric disorder.” In the future, however, Feng thinks genetic monkey models will become more powerful as human brain imaging studies reveal electrical signatures of disease that can also be detected and analyzed in the primates.

Straight from the Source

Stem cells, meanwhile, are helping some neuroscientists to go beyond animal models altogether, with “disease-in-a-dish” systems made from human cells. iPSC technology, first described in 2006 (11), could prove particularly helpful for studying the many brain disorders with complex or unknown genetics, allowing researchers to sidestep the guesswork of replicating all of the right mutations in animals. “Having cells directly from patients who are diagnosed by physicians tells us we’re dealing with cells from humans that we know have the disease,” says Gage. “It takes us closer to examining the molecular basis of the disease.”

In a 2014 study, Gage and his colleagues developed an iPSC-based model of bipolar disorder, culturing neurons from the cells of six patients with the condition (12). The disease runs in families, but researchers have had trouble disentangling the web of genetic and biological mechanisms behind it. This lack of clarity has also made it hard to predict which people will respond well to treatment with lithium.

Confirming what has been seen in animal models, Gage’s team found elevated electrical activity in the patient-derived neurons. They also found that lithium reversed this defect in neurons grown from lithium responders, but not in neurons from nonresponders. Based on the results, Gage suggests that neuronal hyperexcitability could be an important early cellular indicator of the disorder, and that iPSCs could lead to new in vitro methods of screening patients for drug treatments. “We can begin to discover what is unique about nonresponders, and try to diagnose ahead of time whether or not a patient will be responsive,” he says. “Usually, this takes years of trying.”

Minibrains grown from iPSCs have already pointed Vaccarino to new leads in autism. In a 2015 study, she showed that cerebral organoids from the cells of people with one type of autism—a severe form involving enlarged head size—overproduce inhibitory neurons (13). These organoids approximated fetal cerebral cortex development between 9 and 16 weeks, and her team traced the defect to overexpression of a gene called FOXG1 that regulates other genes involved in brain growth. In addition, the degree of change in gene expression correlated with autism severity in their subjects. The researchers didn’t find mutations in FOXG1 itself, but they are now looking for other molecules that influence and are influenced by FOXG1 expression.

Notwithstanding excitement over human cell and organoid models, “it’s important to keep in mind how early days it is,” notes Arnold Kriegstein, director of the Developmental and Stem Cell Biology Program at the University of California, San Francisco. Researchers are still grappling with standardizing methods for culturing the brain cells, and trying to understand why different batches of neurons—even those grown from the same donor—can produce different results, he says.

There’s also the question of how closely the laboratory-grown human neurons mimic real brain function (14). Current techniques only produce neurons that match very early human developmental stages. But that hasn’t stopped some researchers from trying to use iPSC-derived neurons to study Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders that appear late in life. Kriegstein predicts that over the next 5 to 10 years, researchers will resolve many fundamental questions about the technology, including learning to generate more mature neurons from iPSCs.

“I think the way forward is going to take multiple levels of study. All these models are very useful if we ask the right questions,” says Feng. Smarter mouse models can provide convenient and powerful models for studying cellular and molecular defects, and genetically modified monkeys may be useful for studying neural circuits underlying social behavior and higher cognitive abilities, he points out. Stem cells could offer a new path for understanding how complex genetic factors lead to abnormal neuron function in real human tissue. “As we combine these systems, this can lead to breakthroughs to understanding the neurobiological basis of psychiatric disorders,” says Feng. “This is a beginning of a great period for advancing the understanding of brain disorders, especially in the field of psychiatric disorders.”

References

- 1.Lancaster MA, et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature. 2013;501(7467):373–379. doi: 10.1038/nature12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser T, Feng G. Modeling psychiatric disorders for developing effective treatments. Nat Med. 2015;21(9):979–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekar A, et al. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature. 2016;530(7589):177–183. doi: 10.1038/nature16549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, et al. Mice with shank3 mutations associated with ASD and schizophrenia display both shared and distinct defects. Neuron. 2016;89(1):147–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dance A. Core Concept: CRISPR gene editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(20):6245–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503840112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niu Y, et al. Generation of gene-modified cynomolgus monkey via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting in one-cell embryos. Cell. 2014;156(4):836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kishi N, Sato K, Sasaki E, Okano H. Common marmoset as a new model animal for neuroscience research and genome editing technology. Dev Growth Differ. 2014;56(1):53–62. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, et al. Autism-like behaviours and germline transmission in transgenic monkeys overexpressing MeCP2. Nature. 2016;530(7588):98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature16533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mertens J, et al. Pharmacogenomics of Bipolar Disorder Study Differential responses to lithium in hyperexcitable neurons from patients with bipolar disorder. Nature. 2015;527(7576):95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature15526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariani J, et al. FOXG1-dependent dysregulation of GABA/glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell. 2015;162(2):375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandoe J, Eggan K. Opportunities and challenges of pluripotent stem cell neurodegenerative disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(7):780–789. doi: 10.1038/nn.3425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]